Abstract

Caregivers, or persons who provide unpaid support to a loved one who could not manage to live independently or whose health or well-being would deteriorate without this help, are increasingly common. These rates have only increased with the COVID-19 pandemic forcing many to care for sick family members in the short or long term. Unfortunately, caregiving is associated with significant burden and health risks, not only for caregivers themselves but also for the care recipients of overwhelmed caregivers. These risks have also been exacerbated by the social isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although interventions exist which have been proven to reduce caregiver burden, education on these interventions is lacking, partly because there has not been a memorable framework on how to care for caregivers. In this paper, an innovative framework to teach clinicians about caring for caregivers is introduced, the C.A.R.E. framework: Caregiver well-being, Advanced care planning, Respite, and Education. This simple framework will help providers become aware of caregiver needs, comfortable in addressing their needs, and able to suggest interventions proven to reduce caregiver burden. Knowledge of this framework should start with medical students so that they can incorporate this critical aspect of primary care into their clinical practice early on in their careers. If providers can simply remember to perform these four interventions, to C.A.R.E. for our caregivers, then they will make a significant impact on the lives of both our patients and their loved ones, during the present COVID-19 pandemic and thereafter.

Keywords: Caregiver burden, caregiving, geriatrics, medical education

Mrs. Jones sat next to her husband at his doctor’s appointment, tightly clenching the sides of the chair and pursing her lips. Her shoulder-length hair showed two inches of gray at the roots. Her handbag was filled with her husband’s medications, a binder of his prior medical records, and pictures of their grandchildren. [Identifying details have been changed.] A few short months earlier, her husband had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and was in clinic today for a follow-up visit. Mrs. Jones stayed silent throughout the appointment, gazing at the floor. When the clinician asked whether she had any questions or concerns, she shook her head “no,” but as the clinician continued helping her husband with his many health needs, tears filled Mrs. Jones’ eyes. The clinician could sense Mrs. Jones’ distress, but he was busy with competing demands throughout the appointment, and Mrs. Jones was not his patient. Although the clinician knew that Mrs. Jones was struggling with the stress of caring for her husband, he felt uncertain in how to best help Mrs. Jones. He continued to focus on his patient and the appointment came to a close.

Afterward, the clinician worried. He worried about Mrs. Jones’ ability to care for her husband and family, of course, but also about her ability to care for herself. He wondered when Mrs. Jones would take the time to step away from caring for her husband to go to her own doctor’s appointment. He wondered whether the team had just missed an important chance to care for Mrs. Jones. He wondered what he could have done to help Mrs. Jones, the hidden patient in this visit.

Caregivers like Mrs. Jones, persons who provides unpaid support to a loved one who could not manage to live independently or whose health or well-being would deteriorate without this help, are common.[1] In fact, over 43.5 million Americans, or over 7% of the US population, are caregivers to an adult over 50, and with our aging population, this number will continue to grow.[2] Americans have come to rely even further on this network of informal caregivers to take care of a nation during the COVID-19 pandemic, as adult day health centers close, tele-visits replace in home care, and many patients opt to postpone their usual in-home care or respite services due to risk of COVID-19 exposure.[3] In many states, caregivers have even been called on to aid in the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine and be deputized to administer to care recipients.

Unfortunately, as in Mrs. Jones’ case, caregivers can suffer immensely. The adverse effect on caregivers’ emotional, social, financial, and spiritual functioning is known as “caregiver burden.”[4] Caregiver burden is associated with significant health risks including depression, anxiety, poor self-care, weight loss, sleep deprivation, and elder abuse inflicted on their care recipient.[5,6] This burden has only intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Caregivers have suffered worse psychological and somatic health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic as compared with noncaregivers, sometimes at up to 60% higher rates.[7] A review of available literature through March 2021 by Hristova et al.[8] attributed increased caregiver depression during COVID-19 to worsening of patient behavioral and psychological symptoms and functional impairment during the pandemic period. Cohort studies from 2020 and 2021 have shown increased caregiver depression levels, especially for families of dementia patients.[9] Many explained this finding due to an increase in daily hours of independent caregiving performed and a loss of traditional supports.[10] Overall, caregiver burden is an independent predictor of caregiver mortality, associated in one study with a 63% increased risk of mortality as measured over a 4-year period.[11]

For physicians to be well-prepared to take care of Mrs. Jones, they must be familiar with evidence-based interventions which relieve caregiver stress. Informal care recipients and caregivers both arrive at primary care and family medicine clinics as patients. Essential interventions to provide for caregivers, as made clear and further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, are central to the provision of quality primary and family care to all patients. This education should begin in medical school as students begin to understand their obligations to both patients and their family members. Many interventions exist that have been proven to reduce caregiver burden, some of which have utilized case-based exercises and short films to foster partnerships between providers and caregivers.[12] However, few interventions are formally taught to clinicians in a memorable mental framework.

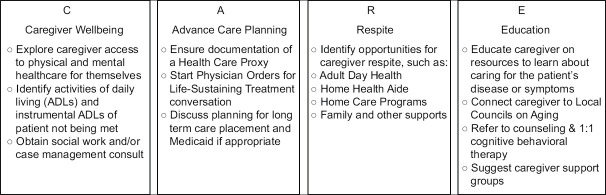

The evidence-based interventions can be summarized in a simple memorable framework which is now used to teach clinicians about caring for caregivers: The C.A.R.E. Framework [Figure 1]: Caregiver well-being, Advanced care planning, Respite, and Education.[13] If health care professionals can set in motion these four interventions, to C.A.R.E. for our caregivers, physicians will make a significant impact on both our patients and their loved ones.

Figure 1.

Framework to C.A.R.E. for Caregivers

A Guide to providing C.A.R.E. to caregivers

C: Caregiving wellbeing

First and foremost, physicians have a responsibility to explore Caregiver wellbeing.[14] Simply asking a caregiver how things are going, and meaningfully engaging with their answer, is one quick yet effective intervention to gauge a caregiver’s coping.[15] Caregiver burden can also be measured using validated scales, such as the Zarit caregiver burden scale.[16,17] There is always opportunity to talk to caregivers about their mood, or to discuss various activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental ADLs for the patient that are not being met. Providers may also involve social work colleagues to further explore caregiver well-being and support needs. Reducing caregiver burden can, and should, be a team effort of physicians, nurses, and social workers, among others. There is also always opportunity to be explicit in encouraging caregivers to see their own physicians and to acknowledge the importance of taking care of themselves alongside their taking care of others. Caring for caregivers should start whenever caregivers interact with our health system, whether at an appointment or during a hospitalization for their loved one, and it begins by asking a simple question of how the caregiver is doing.

A: Advanced care planning

The second aspect of The C.A.R.E Framework involves facilitating discussions with caregivers and care recipients about Advanced care planning for the patient. These discussions should include conversations with patients and their caregivers about the patient’s goals and priorities now and at the end of life, including their current and future health priorities.[18] At the very least, providers should ensure completion of the patient’s Health Care Proxy form, and, if indicated, a Medical or Portable Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form.[19,20] Providers should also be comfortable referring patients and their caregivers to step-by-step resources if they are struggle to talk about advanced care plans, such as Prepare for Your Care[21] or The Conversation Project.[22] In addition, including Advanced care planning in the C.A.R.E. framework should remind clinicians to plan ahead with families for potential long-term care placement, which could require interprofessional involvement of social workers or case managers—particularly if Medicaid enrollment is necessary—as well as Elder Care lawyers. Physicians are well positioned to act as facilitators of these difficult conversations between patients and their caregivers and provide information about available long-term care options, should they be needed. Planning ahead with caregivers and patients will ensure the patient’s wishes are well-documented, and may take burden off the caregiver, since they will be able to honor their loved one’s expressed wishes in the case of an emergency or at the end of their life.[23]

R: Respite

Third, physicians should discuss Respite ideas with caregivers. Ideally, providers should involve a social worker in this step who is well trained in the local resources available to caregivers. Even without a social worker, however, providers can and should have conversations on respite. Introducing the idea of occasionally involving other family members, friends, or paid help to care for the patient, encouraging time away from the home, or brainstorming adult day care options or PACE programs in the area have all been shown to reduce caregiver burden.[24,25,26,27,28] Some health-care systems, such as the VA, offer in-home respite as well as inpatient respite that can be offered to caregivers.[29] COVID-19 has severely limited these formal in-home and senior center respite options as well as informal caregiver peer forums and family and friend support and relief, resulting in the vast majority of informal caregivers reporting higher stress levels.[30] This loss of formal support services can be attributed to center closures, sudden shifts in financial resources, difficulty transitioning to telecare, or a hesitancy around service providers entering the home.[30] Understanding which respite options are available under each circumstance and referring to corresponding virtual groups during this time is especially crucial.

E: Education

Last, physicians should provide caregivers with Education on the resources available to them and on the medical conditions or skills they need to support their loved one. This education should involve both patient-centered and caregiver-centered materials.

For example, providers can educate caregivers on patient-centered nonmedical resources that can reduce the mental burden of caregiving and make home life more comfortable, such as food delivery, housekeeping, or a medication dispenser with an alarm or voice reminder.[5,14,31] Physicians can refer families to community resources, such as local area agencies on aging which can help set up meals on wheels or financial planning, among other services.[32] Physicians can provide caregivers with useful materials to learn about disease-specific caregiving skills; in Mrs. Jones’ case, the Dementia Home Safety booklet,[33] the Alzheimer’s Association website on caregiving[34] and the VA Caregiver Support website[35] could be especially useful. When appropriate, caregivers may wish to work with a case manager to help coordinate the patient’s care; a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed specifically that case managers with a nursing background had greater effects on reducing burden than those of other backgrounds.[36] Providing patient-centered educational material can empower the caregiver with confidence in the care they are providing and remove stress.

In addition to educating caregivers on home resources to ease burden of caring for their family members, physicians can educate caregivers on resources available to directly help themselves. For example, they can recommend individual counseling for the caregiver such as 1:1 cognitive behavioral therapy, which has also been shown to be effective in reducing caregiver stress.[24,37] Caregiver support groups, programs, or coaching may be helpful.[38] Ideally, these groups would meet in-person, the most effective support model, though virtual support groups may be easier for caregivers to attend, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.[24,39]

Challenges to providing C.A.R.E. for caregivers

There are obvious challenges and barriers to successfully intervening to help caregivers. These include, but are not limited to, clinician factors, such as competing demands, lack of awareness of about caregiver needs, lack of comfort in addressing caregiver needs, and lack of knowledge about caregiver interventions.[40] It is also, of course, important to be mindful of cultural values on caregiving when discussing intervention options.[41,42,43] Many providers may not see caregivers as their patients in a traditional sense. But just as a chlamydia diagnosis would prompt clinicians to ask about (and frequently prescribe treatment for) the patient’s sexual partner with expedited partner therapy,[44] a patient with significant health needs should similarly prompt us to ask about and take action to care for their caregiver. The C.A.R.E. Framework to care for caregivers formalizes this responsibility and addresses many of these barriers through inquiring about caregiver wellbeing, engaging in advanced care planning, providing respite ideas, and education for the caregiver. This simple framework may help providers become aware of caregiver needs, more comfortable in addressing their needs, and able to suggest proven interventions to reduce burden. Knowledge of this framework should start with medical students so that they can incorporate this critical aspect of care early on in their careers.[13]

Key Points

Caregiver burden is a common and significant problem with serious consequences not only for caregivers but also for the care provided to patients.

This problem has become especially urgent during the COVID-19 pandemic as caregivers take on increased independent responsibility and will continue to represent a significant concern for the health of patients and their caregivers.

The C.A.R.E framework mentioned here reminds physicians of their role to the primary care of families through a concrete, interprofessional, proven intervention to reduce caregiver stress, starting during medical training. By assessing Caregiver wellbeing (C), working with patients on Advanced Care Planning (A), brainstorming Respite options (R), and providing service-based Education (E), primary care physicians can ensure holistic family care for patients and their support systems. Addressing caregiver burden starts with paying attention to hidden patients like Mrs. Jones and providing her with the C.A.R.E. that she and her family deserve.

Financial support and sponsorship

Dr. Andrea Schwartz reports receiving support from the Harvard Medical School Dean’s Innovation Award.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclosure

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System and the New England Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

- 1.Royal College of General Practitioners. Carers Support; London: 2009. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 12]. From: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/carers . [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. Caregiving in the United States. 2009. [Last accessed on 2020 Nov 15]. From: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/general/2011/caregiving-09-es.doi. 10.26419%252Fres.00062.002.pdf .

- 3.Kent EE, Ornstein KA, Dionne-Odom JN. The family caregiving crisis meets an actual pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e66–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers:A longitudinal study. Gerontologist. 1986;26:260–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden:A clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:1052–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper C, Selwood A, Blanchard M, Walker Z, Blizard R, Livingston G. The determinants of family carers'abusive behaviour to people with dementia:Results of the CARD study. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:136–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SS. Caregivers'mental health and somatic symptoms during Covid-19. J Gerontol Ser B. 2021;76:e235–40. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hristova C, Ordóñez P, Stripling A, Nuccio A, Perez S. Caregiver burden as impacted by COVID-19:Translation of a rapid review to clinical recommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(Supplement):S63–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altieri M, Santangelo G. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budnick A, Hering C, Eggert S, Teubner C, Suhr R, Kuhlmey A, et al. Informal caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic perceive additional burden:findings from an ad-hoc survey in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021:21353. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality:The caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackie M, Baughman KR, Palmisano B, Sanders M, Sperling D, Scott E, et al. Building provider-caregiver partnerships:Curricula for medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2019;94:1483–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holliday AM, Hawley CE, Schwartz AW. Geriatrics 5Ms pocket card for medical and dental students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;67:E7–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynn J. Strategies to ease the burden of family caregivers. JAMA. 2014;311:1021–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, Leurent B, King M. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD007617. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007617.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007617.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarit SH, Zarit JM. The Hidden Victims of Alzheimer s Disease:Families Under Stress. New York: New York University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liew TM, Yap P. A 3-item screening scale for caregiver burden in dementia caregiving:Scale development and score mapping to the 22-item zarit burden interview. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:629–33.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinetti ME, Esterson J, Ferris R, Posner P, Blaum CS. Patient priority-directed decision making and care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:261–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients:Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillick MR. The critical role of caregivers in achieving patient-centered care. JAMA. 2013;310:575–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prepare for Your Care. Oakland: The Regents of the University of California; 2012. [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 14]. From: https://prepareforyourcare.org . [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Conversation Project. Boston: 2019. [Last accessed on 2020 May 16]. From: https://theconversationproject.org . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piersol CV, Canton K, Connor SE, Giller I, Lipman S, Sager S. Effectiveness of interventions for caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease and related major neurocognitive disorders:A systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71 doi: 10.5014/ajot.2017.027581. 7105180020p1-7105180020p10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National PACE Association. 2019. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 10]. From: https://www.npaonline.org .

- 26.Vandepitte S, Van Den Noortgate N, Putman K, Verhaeghe S, Faes K, Annemans L. Effectiveness of supporting informal caregivers of people with dementia:A systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:929–65. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mason A, Weatherly H, Spilsbury K, Arksey H, Golder S, Adamson J, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different models of community-based respite care for frail older people and their carers. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:1–57. doi: 10.3310/hta11150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw C, McNamara R, Abrams K, Cannings-John R, Hood K, Longo M, et al. Systematic review of respite care in the frail elderly. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–224. doi: 10.3310/hta13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VA Boston Healthcare System, Respite Care U.S. Dept of Veteran's Affairs website. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 28]. https://www.boston.va.gov/services/Respite.asp.

- 30.Caregivers in Crisis:Caregiving in a Time of COVID-19. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 28];The Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving. 2020 October; [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lilly MB, Robinson CA, Holtzman S, Bottorff JL. Can we move beyond burden and burnout to support the health and wellness of family caregivers to persons with dementia?Evidence from British Columbia, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:103–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittier S, Scharlach AE, Dal Santo TS. Availability of caregiver support services:Implications for implementation of the National family caregiver support program. J Aging Soc Policy. 2005;17:45–62. doi: 10.1300/J031v17n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horvath KJ, Harvey R, Trudeau SA, Moo LR. A Guide for Families Keeping the Person with Memory Loss Safer at Home. Geriatrics Research Education and Clinical Center. 2016. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 3]. From: https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/docs/HOME_SAFETY_BOOKLET_March_2019.pdf .

- 34.Alzheimer's Association. Caregiving; Chicago: 2019. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 13]. From: www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving . [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Caregiver Support. Washington: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2019. [Last accessed on 2020 May 3]. From: https://www.caregiver.va.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Backhouse A, Ukoumunne OC, Richards DA, McCabe R, Watkins R, Dickens C. The effectiveness of community-based coordinating interventions in dementia care:A meta-analysis and subgroup analysis of intervention components. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:717. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2677-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandepitte S, Van Den Noortgate N, Putman K, Verhaeghe S, Verdonck C, Annemans L. Effectiveness of respite care in supporting informal caregivers of persons with dementia:A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:1277–88. doi: 10.1002/gps.4504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. REACH VA Program. Washington: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2017. [Last accessed on 2020 May 3]. From: https://www.caregiver.va.gov/REACH_VA_Program.asp . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boots LM, du Vugt ME, van Knippenberg RJ, Kempen GI, Verhey FR. A systematic review of internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:331–44. doi: 10.1002/gps.4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang LW, Smith AK, Wong ML. Who will care for the caregivers?Increased needs when caring for frail older adults with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:873–6. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knight BG, Sayegh P. Cultural values and caregiving:The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65:5–13. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morycz RK, Malloy J, Bozich M, Martz P. Racial differences in family burden:Clinical implications for social work. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1987;10:133–54. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process:A sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist. 1997;37:342–54. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Expedited Partner Therapy. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 29];Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 May 12; [Google Scholar]