Abstract

Birdsong is well known for its role in mate attraction during the breeding season. However, many birds, including European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), also sing outside the breeding season as part of large flocks. Song in a breeding context can be extrinsically rewarded by mate attraction; however, song in non-breeding flocks, referred to here as gregarious song, results in no obvious extrinsic reward and is proposed to be intrinsically rewarded. The nucleus accumbens (NAC) is a brain region well-known to mediate reward and motivation, which suggests it is an ideal candidate to regulate reward associated with gregarious song. The goal of this study was to provide new histochemical information on the songbird NAC and its subregions (rostral pole, core, and shell), and to begin to determine subregion-specific contributions to gregarious song in male starlings. We examined immunolabeling for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), neurotensin, and enkephalin (ENK) in NAC. We then examined the extent to which gregarious and sexually-motivated song differentially correlated with immunolabeling for the immediate early genes FOS and ZENK in each subdivision of NAC. We found that TH and ENK labeling within subregions of the starling NAC was generally similar to patterns seen in the core and shell of NAC in mammals and birds. Additionally, we found that gregarious song, but not sexually-motivated song, positively correlated with FOS in all NAC subregions. Our observations provide further evidence for distinct subregions within the songbird NAC and suggest the NAC may play an important role in regulating gregarious song in songbirds.

Keywords: communication, reward, opioids, dopamine, nucleus accumbens, immediate early genes, songbird

Introduction

Male birdsong is a well-studied behavior that is best known for its role in mate attraction and territory maintenance [Bradbury and Vehrencamp, 2011]. However, many gregarious species, such as European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), also sing at high rates outside the context of breeding. Song in a non-breeding context is common in flocks and is considered essential for song learning and maintenance [Riters et al., 2019]. It is also thought to play an important role in the maintenance of social cohesion within a flock [Hausberger et al., 1995]. Although much is known about the neural regulation of song learning and the production of courtship song, relatively little is known about the neural mechanisms that facilitate and maintain song in gregarious contexts.

Unlike courtship or territorial song, gregarious song in flocks does not result in any immediate responses by conspecifics. Starlings do not orient themselves towards other birds, and their songs do not result in immediate mate attraction or the departure of a rival [Dunn and Zann, 2010]. In the absence of an obvious extrinsic reinforcer, it has been proposed that gregarious song may be facilitated by an intrinsic reward state and that the act of producing song may itself be rewarding [Riters and Stevenson, 2012; Riters et al., 2019; Stevenson et al., 2020]. Although singing in this context may result in as yet unidentified extrinsic rewards, multiple studies show that songbirds develop strong preferences for places in the environment that are associated with gregarious singing behavior, indicating that the act of producing gregarious song is tightly coupled to a positive affective state [Riters and Stevenson, 2012; Riters et al., 2014; Hahn et al., 2017].

The nucleus accumbens (NAC) is a key brain region that is well-known in mammals to mediate reward associated with social behavior, sexual behavior, feeding, and the use of drugs of abuse [Alderson et al., 2001; Trezza et al., 2010; Van Der Plasse et al., 2012; Guadarrama-Bazante and Rodríguez-Manzo, 2019]. The NAC in mammals has three distinct subregions: the rostral pole (ACR), the accumbens shell (ACS), and accumbens core (ACC) [Salgado and Kaplitt, 2015]. The ACS and ACC have been well studied in mammals. The ACS underlies the reinforcing properties of rewarding stimuli such as food and drugs [Mcbride et al., 1999; Alderson et al., 2001; Pecina, 2005; Van Der Plasse et al., 2012] and social reward related to pair bonding [Resendez et al., 2012; Resendez et al., 2013], while the ACC plays a significant role in approach to motivational stimuli and learning [Parkinson et al., 1999; Salgado and Kaplitt, 2015]. The ACR appears to consist of both shell- and core-like projections with the lateral ACR sharing efferent projections with the core and the medial part consisting of shell-like projections [Zahm and Heimer, 1993]. Although core and shell receive more attention, ACR has also been shown to be sensitive to drug-induced reward [Zimmermann et al., 1999].

The role of NAC in reward and motivation suggest it is an ideal candidate to regulate reward associated with gregarious singing behavior. In birds such as domestic chicks and pigeons, NAC subregions have been proposed based on hodology, the receipt of projections from the ventral tegmental area [Bálint and Csillag, 2007; Bálint et al., 2011; Husband and Shimizu, 2011], and the distribution of various neuromodulators [Balthazart et al., 1997; Belle and Lea, 2001; Reiner et al., 2004; Bálint and Csillag, 2007]. It appears in songbirds that the subregions of NAC, identified based on matching neuroanatomical landmarks in chicks, may be functionally distinct, but evidence varies across studies. For example, in zebra finches increased levels of dopamine within the ACR are found in newly paired birds [Banerjee et al., 2013] and dopamine transmission in the ACR was shown to increase in response to playback of male song [Tokarev et al., 2017]. In contrast, other studies have found no relationship between dopamine levels or immediate early gene protein expression in ACR and playback of male song [Svec et al., 2009; Svec and Wade, 2009]. Another study in which the precise location of NAC was not indicated also implicated NAC in responses to male song [Earp and Maney, 2012]. In starlings, studies suggest a role for the caudal NAC (both ACS and ACC combined) in female nesting behaviors [Pawlisch et al., 2012] and a study in zebra finches differentially implicated each subregion in distinct affiliative interactions between pair-bonded males and females; the ACR was associated with synchronized flight and the ACC and ACS were associated with allopreening [Alger et al., 2011]. Together these past studies suggest a role for NAC in social behaviors and raise the possibility of functionally distinct subdivisions; however, few behavioral or other studies in songbirds consider subdivisions of NAC [Montagnese et al., 1993; Carrillo and Doupe, 2004; Montagnese et al., 2015].

We had two goals for the following studies. The first was to provide new information on NAC and its subregions by studying the distribution of immunolabeling for markers primarily associated with dopamine and endogenous opioids, because of their known roles in motivation and reward within this region [Vanderschuren et al., 2016; Wenzel and Cheer, 2018]. The second goal was to begin to determine the extent to which the individual subregions of the NAC may contribute to gregarious song by correlating singing behavior with immunolabeling for the immediate early genes (IEG) FOS and ZENK. Relationships between ZENK and FOS expression in brain regions and behavior only partially overlap [Heimovics and Riters 2005; 2006; 2007]. For example, ZENK is expressed in the preoptic area of rats during juvenile play, but FOS is not [Zhao et al., 2020]. Therefore, the use of these two indirect indicators of neural activity could potentially provide more information on brain regions regulating song than either IEG could by itself. We also compared the degree to which relationships between song and IEG labeling patterns were specific to gregarious song by comparing them to IEG labeling associated with sexually-motivated song in a reproductive context.

Materials and Methods

All studies were run under animal care and use protocols approved by the University of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Study 1- Immunolabeling for dopamine and opioid-related proteins in the NAC

We examined 40um thick coronal sections of male starling brains that contained NAC and had been immunolabeled for the dopamine-related proteins neurotensin (NT) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and the opioid-related protein enkephalin (ENK) as part of past research (Table 1). Primary and secondary antibodies used for immunolabeling and references to published papers with detailed labeling protocols can be found in Table 1. All antibodies were validated using Western immunoblots and by leaving out the primary antibodies. We examined labeling in the ACR, ACC, and ACS. To provide readers with rostro-caudal references for the location of each subregion we provide below the y-coordinate (in μm) of the most closely matching area in the 3D starling atlas [De Groof et al., 2016] relative to MRIcron’s (v12.0.20201102) default origin voxel (Fig. 1). The ACR is the region previously referred to as the rostral ventromedial part of the lobus parolfactorius that is located in the ventral part of the striatum around the lateral ventricles at the level of the olfactory tubercle [Carrillo and Doupe, 2004; Reiner et al., 2004; Gutierrez-Ibanez et al., 2016]. In our sections this area appeared when Area X became circular as we moved caudally. In the 3D starling atlas [De Groof et al., 2016], ACR is located rostro-caudally at approximately 63 μm on the y-axis from the origin voxel. The locations for ACC and ACS were identified using landmarks from studies on domestic chicks [Bálint and Csillag, 2007] that show these areas to be located just lateral to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis located along the ventral tips of the lateral ventricles at the level of the tractus septomesencephalicus as it forms a slightly inward curving pyramid in coronal sections, with the ACC located just dorsal to the ACS. In the 3D starling atlas, the ACC and ACS are located rostro-caudally at approximately 46 μm on the y-axis from the origin voxel.

Table 1.

Antibody information for each immunolabel from prior publications using the same tissue.

| Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine Hydroxylase | Mouse anti-TH at 1:10,000, ImmunoStar Inc., Hudson, WI; CAT#22941 | Goat anti-mouse at 1:500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA | Heimovics and Riters, 2008 |

| Neurotensin | Rabbit anti-NT at 1:5000, Immunostar Inc., Hudson, WI; CAT#20072 | Goat anti-rabbit at 1:1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA | Merullo et al., 2015 |

| Enkephalin | Rabbit anti-ENK at 1:2500, Immunostar Inc., Hudson, WI; CAT#20065 | Goat anti-rabbit at 1:2500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA | Kelm-Nelson et al., 2013 |

| FOS | Rabbit anti-FOS at 1:18000, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc253 | Goat anti-rabbit at 1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA | Heimovics and Riters, 2005; 2006 |

| ZENK | Rabbit anti-ZENK at 1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; c19 | Goat anti-rabbit at 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA | Heimovics and Riters, 2007 |

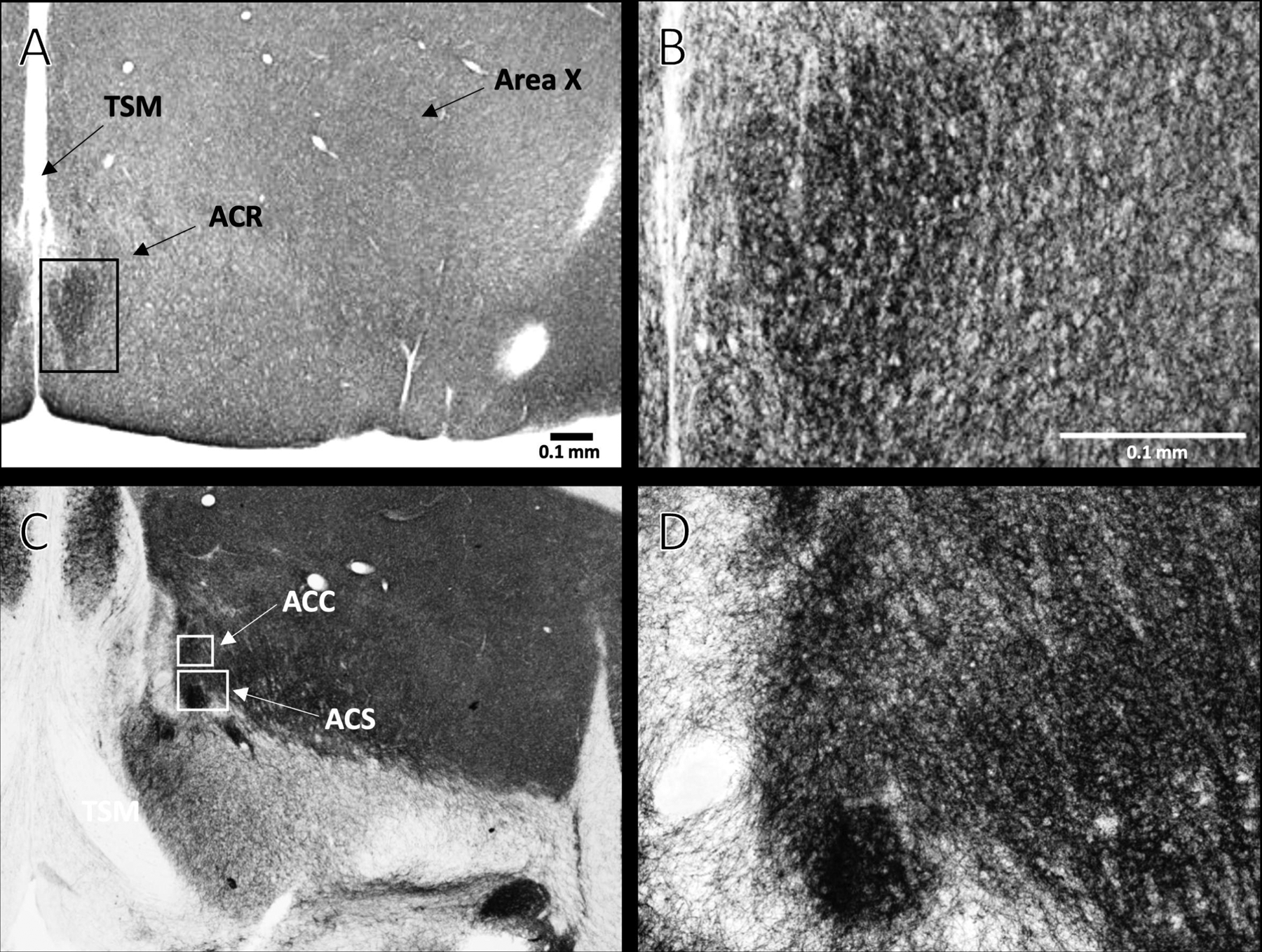

Fig. 1.

Images adapted from the 3D starling atlas (A and C) [De Groof et al., 2016] and illustrations (B and D) showing locations of the rostral pole of the nucleus accumbens (ACR) (panels A and B), and the accumbens core (ACC) and accumbens shell (ACS) (panels C and D) in the left hemisphere of coronal sections. TSM = tractus septomesencephalicus.

For each label, we selected sections from 7 birds that were all in a spring-like condition as part of prior studies (Table 1) and measured the optical density (OD) and percent area covered (PAC) by TH and ENK labeling within each subregion to have a quantitative comparison. Measurements were not taken from NT due to tissue folds and damage in the targeted areas so labeling is described qualitatively. Images of brain sections were acquired using a digital camera (Lecia DFC310 FX) connecting a microscope to a PC computer. All images were taken using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, LLC.). The exposure times for each stain (TH = 20.66 ms, NT = 19.84 ms, ENK = 20.31 ms) were determined by averaging together the results of the auto-expose function on MetaMorph from seven random regions of a brain section of each stain. Shading correction and background subtraction were performed in MetaMorph for all stains. OD and PAC were measured using the Fiji Distribution of ImageJ [Schindelin et al., 2012]. The selection of ACR was within an area of 0.43 × 0.56 mm, ACC within 0.62 × .19 mm, and ACS within 0.62 × 0.38 mm (Fig. 1). Measurements were taken from both hemispheres and were averaged together for statistical analyses.

Study 2- Immunolabeling for immediate early genes in NAC and gregarious song

In this study we counted the number of IEG labeled cells in ACR, ACC, and ACS in tissue from previously published studies on male starlings that were singing either gregarious or sexually-motivated song [Heimovics and Riters, 2005; 2006; Heimovics and Riters, 2007]. In brief, the tissue used in this study was collected from male starlings that were trapped near Madison, WI and behaviorally tested in flocks in outdoor aviaries. Details related to trapping, housing, and starling care are provided in three published studies [Heimovics and Riters, 2005; 2006; Heimovics and Riters, 2007]. We present only details relevant to the present study here.

Photoperiod manipulations were used to place males into 1) non-breeding season (fall/winter-like) conditions under which they naturally form large flocks and spontaneously sing high rates of gregarious song and 2) breeding-season (spring-like) conditions under which males naturally acquire nest sites and sing high rates of sexually-motivated song to attract females. Males in the spring-like condition also received testosterone implants which help to facilitate sexually-motivated song in aviary housed males (further details are found in [Heimovics and Riters, 2005]). Males in the gregarious condition (n=18) were split between two flocks housed in two outdoor aviaries. Each flock was observed for 50 minutes a day, three days in a row. During each period, spontaneous song production was recorded using a point sampling method, in which every minute it was marked whether an individual male was singing or not. Males in the sexually-motivated condition (n=24) were also split between two flocks housed in two outdoor aviaries. Sexually-motivated song is triggered by the presence of a female, so to stimulate song for birds in this condition a breeding-season condition female was released into each aviary and each flock was observed for 50 minutes a day, three days in a row. During each period, song production after female introduction was recorded as described for gregarious song. The sum of the 3 observation days was used in analysis. We note here that when only the last test day was considered, as is typical for studies of immediate early gene expression, there were no significant correlations and only slight positive trends in the ACR and ACC. We interpret this finding in the discussion below.

Ten minutes after the final behavioral observations, all males in a social group were sacrificed via rapid decapitation and brains were removed and fixed in a 5% acrolein solution. Primary and secondary antibodies used for immunolabeling and references to published papers with detailed labeling protocols can also be found in Table 1. All sections were mounted onto gel-coated slides, dehydrated, and cover slipped. The tissue used in this study had been labeled for the IEGs FOS and ZENK as part of the past published papers, but NAC had not been examined. We selected only birds with sections that had high quality label in NAC, resulting in 14 birds for FOS labeling and 18 birds for ZENK labeling.

Quantification

A researcher blind to the reproductive condition and behavior of each bird performed counts of ZENK labeled cells and FOS labeled cells within the ACR, ACC, and ACS. Imaging hardware and software was the same as listed previously. The exposure times for each stain (ZENK=5.43 ms, FOS=4.79 ms) were calculated using the same method listed above, as was shading correction and background correction. All cell counts were performed in the Fiji Distribution of ImageJ [Schindelin et al., 2012]. The numbers of FOS labeled cells and ZENK labeled cells were counted in the NAC subregions with the same area measurements listed previously. Due to the dark staining for ZENK, background was also subtracted on ImageJ with a rolling ball radius of 10. If dust or artefact was present, the threshold for cell counts was manually adjusted by an experimenter blind to the bird’s condition of behavior to maintain accuracy. The numbers of FOS labeled and ZENK labeled cells were counted bilaterally on three consecutive sections if tissue was intact. If tissue was damaged or sections were lost, a fourth section was counted. If the fourth section was also damaged or missing, counts were taken from the two intact sections. Values from these counts were averaged and the mean value for each region was used for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with R (Version 4.0.5) in RStudio (Version 1.4.1106) [R Core Team, 2021]. Separate repeated measures ANOVAs were run to compare OD and PAC across ACR, ACC and ACS for TH and ENK. When significant, these were followed by Holm-Bonferroni posthoc comparisons. For immediate early gene analysis, a simple linear regression analysis was run for each NAC region and seasonal condition, with maximally stimulated song (either gregarious or sexually-motivated) as the independent variable, and IEG count (either FOS or ZENK) as the dependent variable. Model assumptions were tested with residual plots, and assumptions of parametric statistics were met. Subjects were deemed model outliers if they were ± 2 standard deviations about the mean. However, the removal of outliers did not change whether the results were significant or non-significant, so all subjects were included in the analysis below.

Results

Study 1- Characterizing the avian nucleus accumbens using immunolabeling

Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH)

TH label was present in the ACR (Fig. 2), with a large, dense, patch adjacent to the midline that was slightly ventral to the most ventral tip of the TSM. The densest label formed an oblong, oval that stood out from the rest of the ventral striatum. TH label also filled the entire ACC and ACS with label in ACC appearing less dense than the ACS. Results of an ANOVA revealed significant differences in PAC of TH across the regions (F(2, 12) = 4.67, p = 0.032; n = 7) with the ACS PAC significantly greater than ACR (p = 0.033, 95% CI[1.71, 8.80]) and nearly significantly greater than ACC (p = 0.055, 95% CI[1.27, 15.34]) (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in OD of TH between any of the subregions (F(2, 12) = 1.52, p = 0.26; n = 7).

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) labeling in the rostral pole of the nucleus accumbens (ACR), nucleus accumbens shell (ACS) and nucleus accumbens core (ACC). A. TH labeling in the ACR at 2x magnification. B. 10x magnification of the ACR. C. TH labeling in the ACC and ACS at 2x magnification. D. 10x magnification of the ACS and ACC. Arrows highlight the tractus septomesencephalicus (TSM) and location of Area X for orientation.

Fig. 3.

Percent Area Covered (A) and Optical Density (B) of tyrosine hydroxylase labeling in the rostral pole of the nucleus accumbens (ACR), nucleus accumbens shell (ACS) and nucleus accumbens core (ACC). Error bars represent one within-subject standard error about the mean. *P<0.05

Neurotensin (NT)

NT-immunoreactive fibers were present in ACR (Fig. 4). There was a dense grouping of fibers in the same location as the densest TH label described above. NT labeling was also dense in ACS and ACC. The label gradually became less dense more lateral to the midline. Labeling appeared to be fairly uniform across ACS and ACC, but differences were difficult to differentiate because tissue folds were common in caudal sections of NAC (which was not the target region for the initial study).

Fig. 4.

Photomicrographs of neurotensin (NT) in the NAC. See Figure 2 for additional details.

Enkephalin (ENK)

For ENK the densest fiber cluster was located within a similar region to that described for TH (Fig. 5). ENK labeled fibers in ACR were noticeably denser than the rest of the ventral striatum. Dense labeling was found both in the ACC and ACS with no particularly noticeable distinction between the ACC and ACS subregions, which was confirmed quantitatively by the finding that there were no significant differences in either OD or PAC of ENK between any of the subregions for OD (F(2, 12) = 3.33, p = 0.071; n = 7) or PAC (F(2, 12) = 0.44, p = 0.65; n = 7) (Fig. 6).The label gradually became less dense in fibers more lateral from the midline.

Fig. 5.

Photomicrographs of enkephalin (ENK) in the NAC. See Figure 2 for additional details.

Fig. 6.

Percent Area Covered (A) and Optical Density (B) of enkephalin labeling in the rostral pole of the nucleus accumbens (ACR), nucleus accumbens shell (ACS) and nucleus accumbens core (ACC). Error bars represent one within-subject standard error about the mean. No significant differences were found between any of the subregions for either variable.

Study 2- Immediate early genes and song

Singing behavior and FOS immunolabeling

FOS immunolabeled cells appeared to be uniformly spread throughout each subregion, with no consistent clustering within a given area. There was a visibly higher number of FOS immunolabeled cells within all subregions of the NAC in high singing starlings than in low singing starlings (Fig. 7). We performed simple linear regressions, in which FOS cell counts within the ACR, ACC, and ACS were regressed on total song over three observation days in fall-like birds singing gregarious song and spring-like birds singing sexually-motivated song. There were significant, positive correlations between gregarious song and the number of FOS immunolabeled cells in ACR (R2 = 0.50, p = 0.022; n = 10), ACC (R2 = 0.42, p = 0.041; n = 10), and ACS (R2 = 0.46, p = 0.046; n=9) (Fig. 7 & 8). There were no significant relationships between sexually-motivated song and label in any of the NAC subregions (R2 and p-values shown in Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Photomicrographs showing the comparison of FOS in the NAC of low singing (song = 5) (left) and high singing (song = 32) (right) European starlings singing in a gregarious context. Images are centered within the same locations as shown in Figures 2, 4, & 5.

Fig. 8.

Numbers of FOS labeled cells within the rostral pole of the nucleus accumbens (ACR), accumbens core (ACC), and accumbens shell (ACS) correlate positively with gregarious song production. Data shown are the number of FOS-labeled cells within the ACR, ACC, and ACS correlated with total song (point sampling every minute for an hour) for each individual. Each point represents one starling. Individuals singing gregarious song are in the left column and individuals singing sexually-motivated song are in the right column. The inclusion of a regression line indicates a significant correlation (p<0.05).

Singing behavior and ZENK immunolabeling

There were no noticeable, visible differences in the number of ZENK immunolabeled cells within all subregions of the NAC between high and low singing starlings. Again, we performed simple linear regressions, where ZENK cell counts within the ACR, ACC, and ACS were regressed on total song over the three observation days in fall-like birds singing gregarious song and spring-like birds singing sexually-motivated song. There was one significant, positive correlation between gregarious song and the number of ZENK immunolabeled cells in ACR (R2 = 0.23, p = 0.04998; n = 17; Fig. 9). There were no other significant relationships between ZENK labeled cells and sexually-motivated song or gregarious song within the NAC (R2 and p-values shown in Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Numbers of ZENK labeled cells within the rostral pole of the nucleus accumbens (ACR) correlates with gregarious song production. Data shown are the number of FOS-expressing cells within the ACR, ACC, and ACS correlated with total song (point sampling every minute for an hour) for each individual. Each point represents one starling. Individuals singing gregarious song are in the left column and individuals singing sexually-motivated song are in the right column. The inclusion of a regression line indicates a significant correlation (p<0.05).

Discussion

The results of this study show that immunolabeling for dopamine- and opioid-related markers in starling NAC is generally similar to that reported in mammals and birds. We also saw that immediate early gene activity in all three NAC subregions correlated positively with gregarious but not sexually-motivated song. These findings provide further evidence for similar NAC subdivisions in birds and mammals and a potential role for the songbird NAC in gregarious singing behavior that is tightly coupled to a positive affective state.

Patterns of immunolabeling in the starling NAC are similar to those in other species

Few studies have examined NAC core-shell differences in birds, but in rodents distinct patterns have been reported in the distribution of dopamine- and opioid-related proteins with TH and NT tending to be denser in ACS than ACC [Zahm and Brog, 1992; Senger et al., 1993; Jansson et al., 1999; Meredith and Totterdell, 1999; Todtenkopf et al., 2000; Van Der Elst et al., 2005; Depboylu, 2014; Mccollum and Roberts, 2014; Norrara et al., 2018; Schroeder et al., 2019], and ENK immunolabeling tending to be patchy and either denser in core or relatively uniform across the core and shell [Mclean et al., 1985; Voorn et al., 1989; Jongen-Rélo et al., 1993; Meredith et al., 1993]. Consistent with what is reported in rodents, we found the area covered by TH labeling in starlings tended to be greater in ACS than ACC, although this differs somewhat from TH immunolabeling in pigeons which appears to be uniformly dense across both the ACC and ACS [Wynne and Güntürkün, 1995], although this was not quantified in the paper. ENK labeling in starlings also appeared to be uniform across ACS and ACC, which matches reports in rodents and developing chickens [Reiner et al., 1984]. This is also supported by our finding that there were no differences in optical density or the area covered by labeled fibers across subregions. In contrast to what is observed in rodents, in starlings NT labeling appeared to be uniform across the ACS and ACC; however, due to tissue folds in caudal sections of NAC it was difficult to conclude the degree to which similar labeling differences between the ACS and ACC are present in starlings. Few studies in rodents have focused on immunolabeling in the rostral pole of NAC. In birds, dense TH immunolabeling has been observed in ACR in quail, zebra finches, and pigeons within a region that appears similar to the distinct oblong, rostral region that we observed in starlings [Bailhache and Balthazart, 1993; Wynne and Güntürkün, 1995; Alger et al., 2011]. A similar region in starlings was also densely innervated with NT and ENK fibers and distinct from surrounding striatum. NT immunolabel has also been identified within the ACR of chicks [Bálint et al., 2016], and similarly dense met-ENK labeling is observed in this same region in budgerigars and chickens [Reiner et al., 1984; Durand et al., 1998]. Although further characterization of NT is needed, together results suggest neurochemical homology for subdivisions of the avian and rodent NAC. See Table 2 for summary.

Table 2.

Description of immunolabeling within each subdivision of NAC in starlings and in prior studies in mammals.

| Mammalian NAC summary | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine Hydroxylase | Label present in ACR, ACS appeared denser than ACC | Label present in ACR, ACS appeared denser than ACC |

| Neurotensin | Label present in ACR, ACS appeared uniform with ACC although tissue folds made conclusions difficult | Label present in ACR, ACS appeared denser than ACC |

| Enkephalin | Label present in ACR, ACS appeared uniform with ACC | Label present in ACR, ACS appeared uniform with ACC |

IEG cell counts in the NAC correlate positively with gregarious but not sexually-motivated song

IEG protein products are typically measured within two hours after the production of behavior [Charlier et al., 2005; Alger et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2020]. However, in this study positive correlations were found between IEG measurements and the sum of song measurements across all three test days but not song produced on the day of brain collection. One interpretation is that IEG expression in this study reflects an individual bird’s general propensity or motivation to sing which may be better reflected in song sampled across several test periods. This would suggest that the correlations identified here reflect a close association between the motivation to sing and activity in NAC whether or not the bird sang during the observation period.

This measure of an individual’s propensity to produce gregarious song was positively correlated with numbers of FOS labeled cells within all subregions of the NAC, and with ZENK cell counts in ACR. In contrast, there were no significant correlations between FOS or ZENK counts and the propensity to produce sexually-motivated song. As reviewed in the introduction, a growing number of studies suggest that in contrast to sexually-motivated song, which can be rewarded by mate attraction and copulation, gregarious song is associated with an intrinsic reward state [Riters and Stevenson, 2012; Riters et al., 2014; Hahn et al., 2017]. Gregarious song has been proposed to be a form of play behavior that allows birds to develop important social skills for use in more serious reproductive contexts [Riters et al., 2019]. The NAC, and specifically stimulation of mu opioid receptors in NAC, is centrally involved in reward induced by social play in rodents [Trezza et al., 2011; Manduca et al., 2016; Vanderschuren et al., 2016], and NAC is considered vital for positive, reward-seeking behavior [Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1999]. Recently, we found that pharmacological stimulation of mu opioid receptors in ACR in starlings stimulated gregarious song [Maksimoski et al., 2021]. This demonstrates that the correlations reported here may reflect causal involvement of this region in gregarious song and supports the hypothesis that the NAC plays a role in social reward that is conserved across vertebrates. Studies are now needed to causally test roles for ACC and ACS in singing behavior.

We investigated two different IEGs to gain more complete insight into potential relationships between song and activity in NAC. As mentioned previously, the response of these IEGs can differ in the same brain regions in response to the same stimuli [Bailey and Wade, 2003; Zhao et al., 2020]. Additionally, in immediate early gene studies, the absence of expression does not indicate the absence of neuronal activity, and not every immediate early gene is expressed in every brain area [Heimovics and Riters, 2005]. Thus, the lack of correlations between FOS or ZENK labeled cells and sexually-motivated song does not preclude a role for NAC in song in this context. Unlike gregarious song, this type of song is not tightly coupled to a reward state [Riters and Stevenson, 2012; Stevenson et al., 2020] but reflects a highly motivated state of reward seeking (i.e., males sing to attract females which can be rewarded by copulation). NAC is known to be involved in sexually-motivated behaviors in mammals [Damsma et al., 1992; Guadarrama-Bazante and Rodríguez-Manzo, 2019] and motivated responses to other rewards [Mcbride et al., 1999; Alderson et al., 2001; Pecina, 2005; Van Der Plasse et al., 2012]. Thus, it is possible that NAC would be involved in song in this context; and we interpret our results to indicate that the role of NAC in gregarious and sexually-motivated song differs. A next step will be to explore distinct roles for the NAC in song in these two contexts.

It is also important in future research to explore functionally distinct roles for the ACR, ACS, and ACC in gregarious song. As reviewed in the introduction, in rodents the ACS is well-known for its role in hedonic reward [Mcbride et al., 1999; Alderson et al., 2001; Pecina, 2005; Van Der Plasse et al., 2012] so it is possible that it is primarily responsible for the positive affective state that is associated with gregarious song in songbirds [Riters and Stevenson, 2012; Riters et al., 2014; Hahn et al., 2017]. In contrast, the ACC in rodents is not closely associated with hedonic pleasure but implicated in motivated responses to rewards and learning [Parkinson et al., 1999; Salgado and Kaplitt, 2015] so it is possible that its role in song relates primarily to motivation. The ACR has been implicated in drug-induced reward in rodents [Zimmermann et al., 1999]; however, there are few functional studies concentrated on the rostral pole in mammals. It is possible that ACR may contribute to functions served by both ACC and ACS based on studies in rodents that show that the lateral ACR shares efferent projections with the core and the medial ACR shares projections with shell [Zahm and Heimer, 1993]. Future studies are needed to explore the specific functional contributions of subregions of NAC to gregarious song.

Conclusion

The results of this study 1) provide additional support for neurochemically distinct rostral pole, core, and shell subdivisions of the NAC in birds that are neurochemically homologous to the mammalian NAC, and 2) implicate the NAC in a form of non-sexual, affiliative, rewarding social communication. Results are also consistent with the hypothesis that NAC is part of a central, conserved circuitry that underlies rewarding social behaviors across vertebrates. Given the role of intra-NAC dopamine in motivation and opioids in reward, studies are now needed to examine the roles of these modulators in ACR, ACC, and ACS in gregarious as well as sexually-motivated song. Finally, here we focused solely on immunolabeling for proteins in NAC related to dopamine and opioids, given our interest in motivation and reward; however, in future studies the use of calcium binding proteins (Husband and Shimizu, 2011) and tract-tracing studies are needed to further uncover potential subdivisions and homologies with mammals.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH/NIMH grant R01 MH119041 to L.V.R. We thank Alyse Maksimoski and Sharon Stevenson for feedback on drafts of this manuscript. We thank Changjiu Zhao for assistance with figure clarity. We also gratefully acknowledge Chris Elliott, Jeffrey Alexander, and Kate Skogen for starling care.

Funding Sources

This work was funded by National Institute of Mental Health grant #R01 MH119041.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

All subjects were tested and collected for prior studies. All study protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Wisconsin- Madison Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, approval numbers L00350 (TH), L005163 (NT), L00379 (ENK), and L00344 (FOS and ZENK).

Conflict of Interest Statement

Authors report no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made freely available upon request.

References

- Alderson HL, Parkinson JA, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. The effects of excitotoxic lesions of the nucleus accumbens core or shell regions on intravenous heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001 2001-February-01;153(4):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger SJ, Juang C, Riters LV. Social affiliation relates to tyrosine hydroxylase immunolabeling in male and female zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2011 2011-September-01;42(1):45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger SJ, Maasch SN, Riters LV. Lesions to the medial preoptic nucleus affect immediate early gene immunolabeling in brain regions involved in song control and social behavior in male European starlings. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009 2009-March-01;29(5):970–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DJ, Wade J. Differential expression of the immediate early genes FOS and ZENK following auditory stimulation in the juvenile male and female zebra finch. Molecular Brain Research. 2003 2003-August-01;116(1–2):147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailhache T, Balthazart J. The catecholaminergic system of the quail brain: Immunocytochemical studies of dopamine β-hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993 1993-March-08;329(2):230–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Absil P, Viglietti-Panzica C, Panzica GC. Vasotocinergic innervation of areas containing aromatase-immunoreactive cells in the quail forebrain. Journal of neurobiology. 1997;33(1):45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SB, Dias BG, Crews D, Adkins-Regan E. Newly paired zebra finches have higher dopamine levels and immediate early gene Fos expression in dopaminergic neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2013 2013-December-01;38(12):3731–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle MDC, Lea RW. Androgen receptor immunolocalization in brains of courting and brooding male and female ring doves (Streptopelia risoria). General and comparative endocrinology. 2001;124(2):173–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury J, Vehrencamp S. Principles of animal communication, 2nd edn Sunderland. MA: Sinauer Associates[Google Scholar]. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bálint E, Balázsa T, Zachar G, Mezey S, Csillag A. Neurotensin: revealing a novel neuromodulator circuit in the nucleus accumbens–parabrachial nucleus projection of the domestic chick. Brain Structure and Function. 2016;221(1):605–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bálint E, Csillag A. Nucleus accumbens subregions: hodological and immunohistochemical study in the domestic chick (Gallus domesticus). Cell Tissue Res. 2007. Feb;327(2):221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bálint E, Mezey S, Csillag A. Efferent connections of nucleus accumbens subdivisions of the domestic chicken (Gallus domesticus): an anterograde pathway tracing study. J Comp Neurol. 2011. Oct 15;519(15):2922–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo GD, Doupe AJ. Is the songbird Area X striatal, pallidal, or both? an anatomical study. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2004 2004-May-31;473(3):415–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier TD, Ball GF, Balthazart J. Sexual behavior activates the expression of the immediate early genes c-fos and Zenk (egr-1) in catecholaminergic neurons of male Japanese quail. Neuroscience. 2005 2005-January-01;131(1):13–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsma G, Pfaus JG, Wenkstern D, Phillips AG, Fibiger HC. Sexual behavior increases dopamine transmission in the nucleus accumbens and striatum of male rats: comparison with novelty and locomotion. Behavioral neuroscience. 1992;106(1):181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groof G, George I, Touj S, Stacho M, Jonckers E, Cousillas H, et al. A three-dimensional digital atlas of the starling brain. Brain Structure and Function. 2016 2016-May-01;221(4):1899–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depboylu C. Non-serine-phosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase expressing neurons are present in mouse striatum, accumbens and cortex that increase in number following dopaminergic denervation. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2014 2014-March-01;56:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AM, Zann RA. Undirected Song in Wild Zebra Finch Flocks: Contexts and Effects of Mate Removal. Ethology. 2010 2010-April-26;102(4):529–39. [Google Scholar]

- Durand SE, Liang W, Brauth SE. Methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity in the brain of the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus): similarities and differences with respect to oscine songbirds. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998;393(2):145–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp SE, Maney DL. Birdsong: Is It Music to Their Ears? Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience. 2012 2012-January-01;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadarrama-Bazante IL, Rodríguez-Manzo G. Nucleus accumbens dopamine increases sexual motivation in sexually satiated male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2019 2019-April-01;236(4):1303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Ibanez C, Iwaniuk AN, Jensen M, Graham DJ, Pogány Á, Mongomery BC, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide (CARTp) in the brain of the pigeon (Columba livia) and zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2016 2016-December-15;524(18):3747–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn AH, Merullo DP, Spool JA, Angyal CS, Stevenson SA, Riters LV. Song-associated reward correlates with endocannabinoid-related gene expression in male European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Neuroscience. 2017 2017-March-01;346:255–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausberger M, Richard-Yris M-A, Henry L, Lepage L, Schmidt I. Song sharing reflects the social organization in a captive group of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1995;109(3):222. [Google Scholar]

- Heimovics S, Riters L. ZENK labeling within social behavior brain regions reveals breeding context-dependent patterns of neural activity associated with song in male European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). 2007;176(2):333–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimovics SA, Riters LV. Immediate early gene activity in song control nuclei and brain areas regulating motivation relates positively to singing behavior during, but not outside of, a breeding context. 2005;65(3):207–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimovics SA, Riters LV. Breeding-context-dependent relationships between song and cFOS labeling within social behavior brain regions in male European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). 2006;50(5):726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husband SA, Shimizu T. Calcium-binding protein distributions and fiber connections of the nucleus accumbens in the pigeon (columba livia). The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2011 2011-05-01;519(7):1371–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Panksepp J: The role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in motivated behavior: a unifying interpretation with special reference to reward-seeking. Brain Research Reviews 1999;31:6–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson A, Goldstein M, Tinner B, Zoli M, Meador-Woodruff JH, Lew JY, et al. On the distribution patterns of D1, D2, tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine transporter immunoreactivities in the ventral striatum of the rat. Neuroscience. 1999 1999-March-01;89(2):473–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongen-Rélo AL, Groenewegen HJ, Voorn P. Evidence for a multi-compartmental histochemical organization of the nucleus accumbens in the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993 1993-November-08;337(2):267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksimoski AN, Polzin BJ, Stevenson SA, Zhao C, Riters LV: μ-Opioid Receptor Stimulation in the Nucleus Accumbens Increases Vocal–Social Interactions in Flocking European Starlings, Sturnus Vulgaris. eneuro 2021;8:ENEURO.0219–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manduca A, Servadio M, Damsteegt R, Campolongo P, Vanderschuren LJ, Trezza V. Dopaminergic Neurotransmission in the Nucleus Accumbens Modulates Social Play Behavior in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016. Aug;41(9):2215–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcbride WJ, Murphy JM, Ikemoto S. Localization of brain reinforcement mechanisms: intracranial self-administration and intracranial place-conditioning studies. Behavioural Brain Research. 1999 1999-June-01;101(2):129–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccollum LA, Roberts RC. Ultrastructural localization of tyrosine hydroxylase in tree shrew nucleus accumbens core and shell. Neuroscience. 2014 2014-June-01;271:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclean S, Skirboll LR, Pert CB. Comparison of substance P and enkephalin distribution in rat brain: An overview using radioimmunocytochemistry. Neuroscience. 1985 1985-March-01;14(3):837–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Ingham CA, Voorn P, Arbuthnott GW. Ultrastructural characteristics of encephalin-immunoreactive boutons and their postsynaptic targets in the shell and core of the nucleus accumbens of the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993 1993-June-08;332(2):224–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Totterdell S. Microcircuits in nucleus accumbens’ shell and core involved in cognition and reward. Psychobiology. 1999;27(2):165–86. [Google Scholar]

- Montagnese C, Geneser F, Krebs J. Histochemical distribution of zinc in the brain of the zebra finch (Taenopygia guttata). Anatomy and Embryology. 1993 1993-August-01;188(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagnese CM, Székely T, Csillag A, Zachar G. Distribution of vasotocin- and vasoactive intestinal peptide-like immunoreactivity in the brain of blue tit (Cyanistes coeruleus). Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 2015 2015-July-14;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrara B, Fiuza FP, Arrais AC, Costa IM, Santos JR, Engelberth RCGJ, et al. Pattern of tyrosine hydroxylase expression during aging of mesolimbic pathway of the rat. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2018 2018-October-01;92:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, Burns LH, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Dissociation in Effects of Lesions of the Nucleus Accumbens Core and Shell on Appetitive Pavlovian Approach Behavior and the Potentiation of Conditioned Reinforcement and Locomotor Activity byd-Amphetamine. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1999 1999-March-15;19(6):2401–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlisch BA, Kelm-Nelson CA, Stevenson SA, Riters LV. Behavioral indices of breeding readiness in female European starlings correlate with immunolabeling for catecholamine markers in brain areas involved in sexual motivation. General and comparative endocrinology. 2012;179(3):359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecina S. Hedonic Hot Spot in Nucleus Accumbens Shell: Where Do μ-Opioids Cause Increased Hedonic Impact of Sweetness? Journal of Neuroscience. 2005 2005-December-14;25(50):11777–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Davis BM, Brecha NC, Karten HJ. The distribution of enkephalinlike immunoreactivity in the telencephalon of the adult and developing domestic chicken. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1984 1984-September-10;228(2):245–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Perkel DJ, Bruce LL, Butler AB, Csillag A, Kuenzel W, et al. Revised nomenclature for avian telencephalon and some related brainstem nuclei. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2004 2004-May-31;473(3):377–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendez SL, Dome M, Gormley G, Franco D, Nevarez N, Hamid AA, et al. μ-Opioid Receptors within Subregions of the Striatum Mediate Pair Bond Formation through Parallel Yet Distinct Reward Mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013 2013-May-22;33(21):9140–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendez SL, Kuhnmuench M, Krzywosinski T, Aragona BJ. μ-Opioid Receptors within the Nucleus Accumbens Shell Mediate Pair Bond Maintenance. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012 2012-May-16;32(20):6771–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riters LV, Spool JA, Merullo DP, Hahn AH. Song practice as a rewarding form of play in songbirds. Behav Processes. 2019. Jun;163:91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riters LV, Stevenson SA. Reward and vocal production: Song-associated place preference in songbirds. Physiology & Behavior. 2012 2012-May-01;106(2):87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riters LV, Stevenson SA, Devries MS, Cordes MA. Reward Associated with Singing Behavior Correlates with Opioid-Related Gene Expression in the Medial Preoptic Nucleus in Male European Starlings. PLoS ONE. 2014 2014-December-18;9(12):e115285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado S, Kaplitt MG. The Nucleus Accumbens: A Comprehensive Review. Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery. 2015 2015-February-18;93(2):75–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods. 2012 2012-July-01;9(7):676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder LE, Furdock R, Quiles CR, Kurt G, Perez-Bonilla P, Garcia A, et al. Mapping the populations of neurotensin neurons in the male mouse brain. Neuropeptides. 2019 2019-August-01;76:101930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger B, Brog JS, Zahm DS. Subsets of neurotensin-immunoreactive neurons in the rat striatal complex following antagonism of the dopamine D2 receptor: An immunohistochemical double-labeling study using antibodies against Fos. Neuroscience. 1993 1993-December-01;57(3):649–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson SA, Piepenburg A, Spool JA, Angyal CS, Hahn AH, Zhao C, et al. Endogenous opioids facilitate intrinsically-rewarded birdsong. Scientific Reports. 2020 2020-December-01;10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svec LA, Lookingland KJ, Wade J. Estradiol and song affect female zebra finch behavior independent of dopamine in the striatum. Physiology & Behavior. 2009 2009-October-01;98(4):386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svec LA, Wade J. Estradiol induces region-specific inhibition of ZENK but does not affect the behavioral preference for tutored song in adult female zebra finches. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009 2009-May-01;199(2):298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Todtenkopf MS, De Leon KR, Stellar JR. Repeated cocaine treatment alters tyrosine hydroxylase in the rat nucleus accumbens. Brain Research Bulletin. 2000 2000-July-01;52(5):407–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarev K, Hyland Bruno J, Ljubičić I, Kothari PJ, Helekar SA, Tchernichovski O, et al. Sexual dimorphism in striatal dopaminergic responses promotes monogamy in social songbirds. eLife. 2017 2017-August-11;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Baarendse PJJ, Vanderschuren LJMJ. The pleasures of play: pharmacological insights into social reward mechanisms. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2010 2010-October-01;31(10):463–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Damsteegt R, Achterberg EJ, Vanderschuren LJ. Nucleus accumbens μ-opioid receptors mediate social reward. J Neurosci. 2011. Apr 27;31(17):6362–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Elst MCJ, Roubos EW, Ellenbroek BA, Veening JG, Cools AR. Apomorphine-susceptible rats and apomorphine-unsusceptible rats differ in the tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive network in the nucleus accumbens core and shell. Experimental Brain Research. 2005 2005-January-01;160(4):418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Plasse G, Schrama R, Van Seters SP, Vanderschuren LJMJ, Westenberg HGM. Deep Brain Stimulation Reveals a Dissociation of Consummatory and Motivated Behaviour in the Medial and Lateral Nucleus Accumbens Shell of the Rat. PLoS ONE. 2012 2012-March-13;7(3):e33455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ Achterberg EJM, Trezza V. The neurobiology of social play and its rewarding value in rats. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2016 2016-November-01;70:86–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Gerfen CR, Groenewegen HJ. Compartmental organization of the ventral striatum of the rat: Immunohistochemical distribution of enkephalin, substance P, dopamine, and calcium-binding protein. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989 1989-November-08;289(2):189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel JM, Cheer JF. Endocannabinoid Regulation of Reward and Reinforcement through Interaction with Dopamine and Endogenous Opioid Signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018;43:103–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne B, Güntürkün O: Dopaminergic innervation of the telencephalon of the pigeon (Columba livia): A study with antibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine. Journal of Comparative Neurology 1995;357:446–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Brog JS. On the significance of subterritories in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum. Neuroscience. 1992 1992-October-01;50(4):751–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Heimer L. Specificity in the efferent projections of the nucleus accumbens in the rat: Comparison of the rostral pole projection patterns with those of the core and shell. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993 1993-January-08;327(2):220–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Chang L, Auger AP, Gammie SC, Riters LV. Mu opioid receptors in the medial preoptic area govern social play behavior in adolescent male rats. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2020 2020-September-01;19(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Privou C, Huston JP. Differential sensitivity of the caudal and rostral nucleus accumbens to the rewarding effects of a H1-histaminergic receptor blocker as measured with place-preference and self-stimulation behavior. Neuroscience. 1999 1999-September-01;94(1):93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made freely available upon request.