Abstract

Liver disease, a major cause of global mortality, has been associated with dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota (bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes). Studies have associated changes in gut bacteria with pathogenesis and severity of liver disease, but the contributions of the mycobiome (the fungal populations of the gut) to health and disease have not been well studied. We review recent findings of alterations in the composition of the mycobiota in patients with liver disease and discuss the mechanisms by which these might affect pathogenesis and disease progression. Strategies to manipulate the gut mycobiota might be developed to treat or prevent liver disease.

Keywords: Fungi, mycobiome, alcohol-associated liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, liver cirrhosis, immune response, fungi-bacterial interaction

Introduction

Liver disease and its complications are one of the leading causes of death and illness worldwide (1). In the United States, approximately 4.5 million adults were diagnosed with chronic liver disease and approximately 44,358 died in 2019, according to data from the National Center for Health Statistics (2). This epidemic of liver disease includes liver disorders such as alcohol-related liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

The intestine contains many microbes, including bacteria, fungi, archae, and viruses, collectively termed the gut microbiota. Alterations to the microbiota, or dysbiosis, have been associated with these types of liver diseases (3). Bacteria are the most abundant members of the human microbiota. Accordingly, our understanding of how alterations in the microbiota affect development of liver diseases has focused on bacteria (4). The fungal community has been considered to be a minor component of the gut microbiota (0.03%–2% of the total) (5) and has not been well studied or characterized.

In fact, fungi have unique and fascinating characteristics that set them apart from other microbes, and they interact with human tissues in many ways. Unlike bacteria, fungi are uni- and multi-cellular, and are eukaryotes with complex cell structures. A typical fungal cell (2–10 μm long and tens of micrometers wide) is 10- to 100-fold larger than a bacterium (1–10 μm long and 0.2–1 μm wide) (5). With more substantial mass of biomaterials than bacteria, fungal cells can utilize more complex biologic processes, provide abundant bioactive molecules to human or animal cells, and reshape their physiology. In addition, fungi are morphologically versatile—they can switch from the unicellular (such as yeast) to the multicellular (such as during hyphal growth), which affects their pathogenicity. Generally, hyphae are more invasive whereas yeast are noninvasive and often commensal(6). Fungi can also form biofilms. Fungal pathogen communities flourish as biofilms, which can cause infections that are resistant to the immune response and can be extremely difficult to eradicate (7, 8). Fungi produce a variety of harmful and beneficial compounds. Fungi-derived toxic metabolites, also called mytoxins, can remain in an organism and cause damage even after the fungus has been eradicated (9). Given these characteristics of fungi, it is important to realize that they can establish symbiotic, commensal, latent, or pathogenic relationships with human cells to maintain homeostasis, and that alterations to these communities can contribute to disease development.

Fungi colonize different body sites (skin, lung, vagina, oral tract, and gut), but there have been most studies of their activities in the gastrointestinal tract. Intestinal fungi have been associated with liver disease (10). Interactions between fungi and liver are anatomical and functionally bidirectional. Approximately 70% of the blood supply to the liver comes from the gut through the portal vein. Potential antigens derived from the gut-resident commensal fungi, ingested fungi, or fungal-derived metabolites can cross the gastrointestinal barrier and translocate, via the portal vein, to the liver and affect its function. The immune cells that reside in or travel through the liver have the potential to initiate innate and/or adaptive immune responses to the intestinal fungi, to maintain homeostasis. We review mycobiota signatures associated with liver diseases, the potential roles of fungi in liver disease pathogenesis, and their interactions with the immune system and the gut bacteria. We also review the impact of fungi on clinical research, attempting to provide a glimpse of the complexity of fungal dysbiosis and its effects on liver disease progression. Although this field is still in early stages, there are many exciting and important avenues for basic and clinical research.

Common tools for exploring the mycobiome and mycobiota in humans

The presence of fungi has been investigated by culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. Culture-based methods (growth of cultured isolates) are more effective at capturing the dominant species while excluding the most tractable organisms. Culture-independent approaches include high-throughput sequencing methods that involve PCR amplification of the 18S, internal transcribed spacer (ITS)1, ITS2, and 28S of fungal ribosomal DNA (rDNA), as well as whole-genome shotgun sequencing(11). Different methods that evaluate different regions of fungal DNA can have biases that complicate comparison of mycobiome results from different studies. 18S rDNA sequencing is usually applied to classify fungi at the species level and above. While ITS1 and ITS2 regions have greater sequence variation between closely related species that can be used to identify fungi on the species or subspecies level. Combinations of 18S rDNA and ITS sequencing are more reliable for fungal classification (12).

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry is emerging as one of the easiest and most accurate technologies for identification of fungi (13). The overall mass spectrum is used as a signature profile of fungi isolates and can be compared to a database of reference spectra to produce a list of the most closely related fungi, with rankings. However, there are few comprehensive and well-curated fungi databases, especially for dimorphic and filamentous fungi.

In 2017, the large-scale Human Microbiome Project was initiated by the National Institutes of Health to investigate the mycobiome of stool samples from 317 healthy volunteers, based on sequencing of the ITS2 and 18S rRNA regions (14). The diversity of fungi is much lower than that of bacteria in healthy human intestine. There was high inter- and intra-variability in fungi among individuals, indicating the instability of mycobiota. Fungal communities were reported to consist mainly of 4 phyla: Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Zygomycota, and Chytridiomycota, with Ascomycota being the most abundant phylum. The genera that were most abundant in the stool samples were Candida, Saccharomyces, Penicillium, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Malassezia, Cladosporium, Galactomyces, Debaryomyces, and Trichosporon. The most-frequently detected fungal species were Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae), Malassezia restricta (M. restricta), and Candia albicans (C. albicans). There is a long list of rarely detected fungi, which make up most of the species richness.

Despite the variety of fungi species detected in the gut samples, few are commonly distributed. According to a review of 36 studies from 1917 to 2015 (15), nearly 75% species were only reported in 1 study and only 15 of the 267 identified species were detected in more than 5 studies. Most detected fungi are low in prevalence and are likely to be transient foodborne contaminants or species that originated from another environment and cannot colonize the gut (16). We do not know yet what a healthy or normal gut mycobiome comprises. We are only beginning to understand the complexity of the intestinal mycobiota, its diversity, longitudinal features, diet-based fluctuations, and roles in health and pathogenesis.

Associations of fungi with development and progression of liver diseases

Alcohol-related Liver Disease

Alcohol-related liver disease is caused by excessive intake of alcohol, which damages the liver and leads to alcohol associated-steatosis, alcohol-associated hepatitis, and cirrhosis. The strong relationship between the mycobiome and alcohol-related liver disease was firstly recognized in studies of fecal samples from healthy individuals, excessive drinkers without progressive liver disease, patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis, and patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis (17). Fecal samples from excessive drinkers had increased abundance of Candida and decreases in Epicoccum, Galactomyces, and Debaryomyces. Patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis also had an increased immune response to fungi, determined by their high serum levels of anti-S. cerevisiae antibody (ASCA), which correlated with mortality. ASCA recognizes peptide mimetic polysaccharides on the cell wall of yeast, and C. albicans was found to be a leading immunogen. It is not clear how the immune system interacts with commensal fungi to contribute to development of alcohol-related liver disease.

In addition to the observed correlation between immune alterations and intestinal fungi in patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis, a subsequent study demonstrated that detection of ASCA was associated with disease progression in a larger cohort of patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis, alcohol use disorder, and nonalcoholic individuals (controls) (18). This study confirmed a lower fungal diversity and an overgrowth of Candida in patients with alcohol-use disorder compared with healthy individuals (controls), based on ITS amplicon sequence analysis. A recent study validated the C. albicans overgrowth finding using a culture-dependent method (19). Fungal cultures of stool samples from patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis formed significantly more colonies of C. albicans than from controls.

Changes of the mycobiome might correlate with the efficacy of alcohol abstinence interventions in patients with alcohol use disorder. Compared with controls, patients with alcohol use disorders have significant increases in abundances of Candida, Debaryomyces, Pichia, Kluyveromyces, and Issatchenkia at genus level, and C. albicans and Candida zeylanoides at species level (20). After a 2-week alcohol abstinence intervention, improved liver function in patients associated with lower intestinal abundances of the genera Candida, Malassezia, Pichia, Kluyveromyces, Issatchenkia; the species C. albicans and C. zeylanoides, and lower serum levels of IgG against C. albicans.

Functional changes in gut fungi of stool samples from patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis have been studied using shotgun metagenomics (21). The allantoin degradation pathway, which converts allantoin to ammonia and carbon dioxide, allows S. cerevisiae to use allantoin as a sole nitrogen source—this pathway was found to be enriched, among 24 MetaCyc pathways mediated by fungi, in fecal samples from patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

NAFLD has become the most common liver disease and is associated with obesity and metabolic disorders such as dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Fatty liver disease begins when fat accumulates in the liver, which may lead more serious forms of fatty liver disease including NASH. Patients with NASH can develop liver fibrosis and eventually cirrhosis and/or HCC (22).

Compositional changes in fecal mycobiome were analyzed using ITS2 sequencing in a cross-sectional study of subjects with NAFLD (23). Beta diversity analysis captured more differences among non-obese subjects than obese subjects. In the non-obese group, patients with NAFLD at advanced stages had different fecal mycobiome compositions than patients with NAFLD at earlier stages. However, this difference was not observed in the obese group. Differential multinomial regression analysis Songbird was performed to identify compositional changes between non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and NASH groups. Abundances of C. albicans, Mucor sp., Cyberlindnera jadinii, Penicillium sp., unknown Pleosporales, Babjeviella inositovora and Candida argentea were associated with NASH, whereas unknown Saccharomycetales and Malassezia sp. were associated with NAFL. Notably, patients with NAFLD and advanced liver fibrosis had an increased immune response to C. albicans, indicated by increased plasma levels of IgG against C. albicans. The role of intestinal fungi was then investigated in germ-free mice transplanted fecal microbiota from patients with NASH. Anti-fungal agents reduced steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in mice with western diet-induced steatohepatitis. Compositional changes of the fecal mycobiome were also described in an Asian population. Compared with healthy subjects, the relative abundance of Talaromyces, Paraphaeosphaeria, Lycoperdon, Curvularia, Phialemoniopsis, Paraboeremia, Sarcinomyces, Cladophialophora, and Sordaria was increased in patients with NAFLD while the abundance of Leptosphaeria, Pseudopithomyces, and Fusicolla was decreased (24). Taken together, findings from clinical and mouse studies indicate that alterations in the fecal mycobiome are associated with development and progression of NAFLD. Manipulating the intestinal mycobiome might be an effective strategy for attenuating NAFLD.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis.

PSC is an immune-mediated chronic liver disease characterized by cholestasis, inflammation, and fibrosis in the intra-and extrahepatic bile ducts. Most (>80%) of patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), especially ulcerative colitis, which are both associated with immune system malfunctions (25). Fungal dysbiosis occurs when the immune system is weakened. In 2019, bacterial and fungal interactions were reported in a cohort of patients with PSC with IBD, patients with only IBD, and healthy individuals (26). Fecal samples from patients with PSC had a higher Shannon index than from patients with IBD or healthy subjects. Fecal samples from patients with PSC had increased abundance of Sordariomycetes class and Exophiala genus and decreased abundance in S. cerevisiae. Fungi–bacteria network analysis revealed that patients with only PSC had a lower inter-kingdom network than patients with PSC and IBD.

In a Northern Germany cohort (27), the overall fungal diversity was not altered in fecal samples from patients with PSC. Increased levels of Candida and Humicola genera were detected in samples from patients with PSC but not healthy subjects. There was noticeable consistency in the significant increase in Candida and H. grisea species in fecal samples from patients with PSC in these 2 independent cohorts. Studies are needed to determine how these fungi increase in the intestine of patients with PSC and how they affect disease development and/or progression.

Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cirrhosis is a late stage of liver scarring due to long-term liver injury; it can be caused by several conditions including chronic alcohol consumption, chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), autoimmune hepatitis, or fatty liver disease. Several studies have provided insight into the intestinal fungal composition in cases of liver cirrhosis. Bacterial and fungal dysbiosis of stool samples were described in a cohort of 143 subjects with liver cirrhosis (77 outpatients, 66 inpatients) and 26 healthy subjects (controls) (28). An inverse correlation between model for end-stage liver disease scores and fungal Shannon diversity was observed in fecal samples of patients of liver cirrhosis. The relative abundance of Candida was significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis vs outpatients and healthy controls. These findings were validated using PCR-based and culture-dependent methods (29). Antibiotics reduced bacterial and fungal diversity in outpatients with cirrhosis whereas proton pump inhibitors did not change the fungal diversity. The ratio of Basidiomycota to Ascomycota associated with hospitalization within 90 days in patients with cirrhosis, and fungal and bacterial dysbiosis were independently associated with risk of hospitalization.

Viral hepatitis is one of the major contributing factors to cirrhosis and liver cancer (30). Fungal diversity and composition were studied, via culture-independent and culture-dependent methods, in fecal samples from patients with chronic HBV infection with and without cirrhosis and healthy volunteers. Samples from patients with HBV-associated cirrhosis had increased fungal richness compared to samples from patients with only chronic HBV infection (31), who had higher fungal richness than samples from healthy volunteers. High levels of Aspergillus, Candida, Galactomyces, Saccharomyces, and Chaetomium were observed in samples from patients with HBV-associated cirrhosis. The increased fecal abundance of Saccharomyces was validated in a cohort of patients with chronic HBV infection HBV-associated cirrhosis (32). Researchers performed quantitative real-time PCR analysis of fungal species in fecal samples from patients with chronic HBV infection (33). They found C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and S. cerevisiae in a higher proportion of samples from patients with HBV-associated cirrhosis patients than healthy volunteers. A case–control study compared the fungal composition and enteric mycobiomes in patients with HCV infection (34), HCV-associated cirrhosis, healthy subjects (controls). Fecal samples from patients with HCV infection had higher proportions of Candida and a higher fungal load than samples from controls.

HCC is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide (35).However, little is known about the intestinal fungi composition in patients with vs without HCC. Aflatoxins (mycotoxins produced by the secondary metabolism of fungi Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus parasiticus, and Aspergillus) can cause HCC (36). Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is one of the most abundant and powerful toxins in the aflatoxin family, and has been shown to promote mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53. A short-term prospective study in China revealed that the interaction between AFB1 and HBV infection increased risk of HCC 60-fold (37). A study of a large cohort of 348 patients with HCC and 597 healthy subjects also confirmed that exposure to AFB1 increased the risk of HCC development (38). These findings provide evidence that mycotoxins produced by the secondary metabolism of fungi contribute to liver carcinogenesis.

Mechanisms by which fungal dysbiosis leads to liver disease

Although alterations in the mycobiome have been associated with liver disease development and progression (Table 1), little is known about the interactions between fungi and human cells and how these contribute to liver disease pathogenesis. Humans are exposed to a variety of fungi throughout their lifetimes via processes such as inhalation, food consumption, and epidermal wounds. Most fungal species in the body have co-evolved with humans and rarely cause diseases in healthy individuals. We review the mechanisms by which the mycobiota contributes to the development of liver diseases (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Alterations of mycobiome in liver diseases.

| Liver disease | Design and participant details | Methodology | Fungal diversity | Mycobiota composition | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | genus | species | |||||

| Alcohol-associated Liver Disease | Healthy individuals (controls, n=8) Alcohol use disorder patients without progressive liver disease (n=10) Alcohol-associated hepatitis patients (n=6) Alcohol-associated liver cirrhosis patients (n= 4) |

ITS1 |

|

Candida ↑

Epicoccum ↓ Galactomyces ↓ Debaryomyces ↓ |

[17] | ||

| Alcohol-associated Liver Disease | Alcohol-associated hepatitis (n=59) Alcohol use disorder (n=15) Healthy controls (n=11) |

ITS1 |

|

Candida ↑

Penicillium ↓ |

[18] | ||

| Alcohol-associated Liver Disease | Non-alcoholic controls (n=11) Alcohol use disorder (n=42) Alcohol-associated hepatitis (n=91) |

Culture and single colony qPCR | Not reported | Candida albicans ↑ | [19] | ||

| Alcohol-associated Disease | Healthy control subjects (n=18) Alcohol use disorder (n=66) |

ITS2 | Not reported |

Cystostereaceae ↑

Debaryomycetaceae ↑ Didymellaceae ↑ Microascaceae ↑ Pichiae ↑ |

Candida ↑

Debaryomyces ↑ Pichia ↑ Kluyveromyces ↑ Issatchenkia ↑ Scopulariopsis ↑ Aspergillus ↓ |

Candida albicans ↑

Candida zeylanoides ↑ Issatchenkia orientalis ↑ Scopulariopsis cordiae ↑ Kazachstania humilis ↓ |

[20] |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | NAFLD (n=78; 24 NAFL, 54 NASH; 40 F0-F1, 38 F2-F4) Controls (n=16) | ITS2 | No significant difference |

Candida. albicans ↑ Mucor sp. ↑ Cyberlindnera jadinii ↑ Penicillium sp.↑ unknown Pleosporales ↑ Babjeviella inositovora ↑ Candida argentea ↑ log ratio: Babjeviella inositovora/S. cerevisiae ↑ log ratio: Mucor sp./S. cerevisiae ↑ log ratio: unknown Hanseniaspora/S. cerevisiae ↑ |

[23] | ||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | NAFLD patients(n=79) healthy subjects (n=34) |

ITS |

Talaromyces ↑ Paraphaeosphaeria ↑ Lycoperdon ↑ Curvularia ↑ Phialemoniopsis ↑ Paraboeremia ↑ Sarcinomyces ↑ Cladophialophora ↑ Sordaria ↑ Leptosphaeria ↓ Pseudopithomyces ↓ Fusicolla ↓ |

[24] | |||

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | PSC with IBD (n=27) PSC without IBD (n=22) IBD without PSC (n=33) Healthy subjects (n=30). |

ITS2 | No significant difference | Exophiala ↑ | Saccharomyces. cerevisiae ↓ | [26] | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Healthy subjects (n=66) PSC patients (n=65, n=32 (PSC-IBD) Ulcerative colitis patients (n=38) |

PCR ITS2 | No significant difference |

Candida ↑

Humicola ↑ |

Hamataliwa.grisea ↑ | [27] | |

| Cirrhosis | Cross-sectional analysis: Cirrhosis (n=143, 77 outpatients, 66 inpatients) Healthy controls (n=26) Three Longitudinal studies: 1) cirrhotics followed over 6 months 2) outpatient cirrhotics with antibiotics for 5 days 3) cirrhotics and controls administered omeprazole over 14 days |

ITS1 |

|

Candida ↑ | [28] | ||

| Cirrhosis | Liver cirrhosis patients (n=135, blood n = 135, ascites n = 92, duodenal fluid n = 54) Healthy control (n=26, blood n = 26, duodenal fluid n = 26) |

PCR- and culture-based techniques | Not reported | Candida ↑ | [29] | ||

| Hepatitis B virus | Hepatitis B cirrhosis (n=38) Chronic hepatitis B (n=35) HBV carriers (n=33) Healthy volunteers (n=55). |

Culture, PCR | Patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis > patients with chronic hepatitis B >HBV carriers ≈ healthy volunteers. |

Candida ↑

Saccharomyces ↑ Aspergillus ↑ Galactomyces ↑ Chaetomium ↑ |

Aspergillus versicolor ↑

Aspergillus penicillioides ↑ Candida. solani ↑ Candida. albicans ↑ Candida. tropicalis ↑ Saccharomyces sp. ↑ Saccharomyces. cerevisiae ↑ Chaetomium sp. ↑ Wallemia muriae ↑ Asterotremella albida ↑ Rhizopus microsporus var. ↑ |

[31] | |

| Cirrhosis Hepatitis B virus | Hepatitis B patients (n=52) Hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis (n=52) Healthy controls (n=40) |

Culture | Not reported | Saccharomyces ↑ | [32] | ||

| Hepatitis B virus | HBV-liver cirrhosis patients (n=80) Chronic hepatitis B patients (n=68) HBV carriers (n=66) Healthy volunteers (n=84) |

QPCR |

C.parapsilosis ↑

C. glabrata ↑ C. tropicalis S. cerevisiae ↑ |

[33] | |||

| Hepatitis C Virus | Patients with chronic HCV infection (n=26) HCV cirrhosis (n=26) Healthy control (n=55) |

Culture, PCR | Not reported | Candida ↑ | [34] | ||

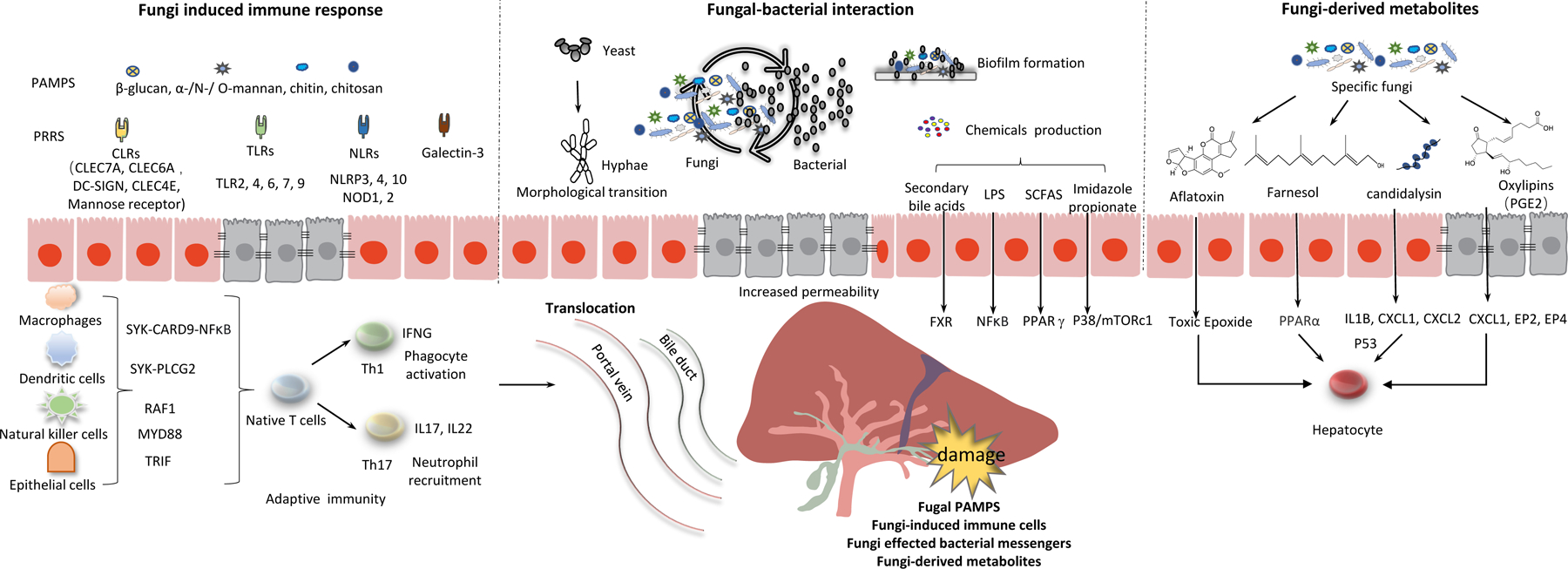

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms by which alterations in gut mycobiota affect development and progression of liver disease.

Interactions between fungi and the immune system.

Like gut bacteria, intestinal fungi interact with the immune system to maintain homeostasis, and alterations in these interactions can lead to disease (Figure 2). In gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), the immune cells provide either defense or tolerance towards gut fungi, metabolites, and toxins. Under homeostatic conditions, this GALT-mediated immune regulation is largely confined to intestinal tissues. The liver receives 75% of its blood supply through the portal vein, and is therefore connected to the GALT and contributes to immune surveillance. The liver is influenced by the intestinal immune response and alterations in the gut mycobiota and other microbes. The intestinal mucosal and vascular barrier, a physical and functional semipermeable structure that allows chemical communication and immune sensing, serves as an interface between the gut and the liver (39, 40).

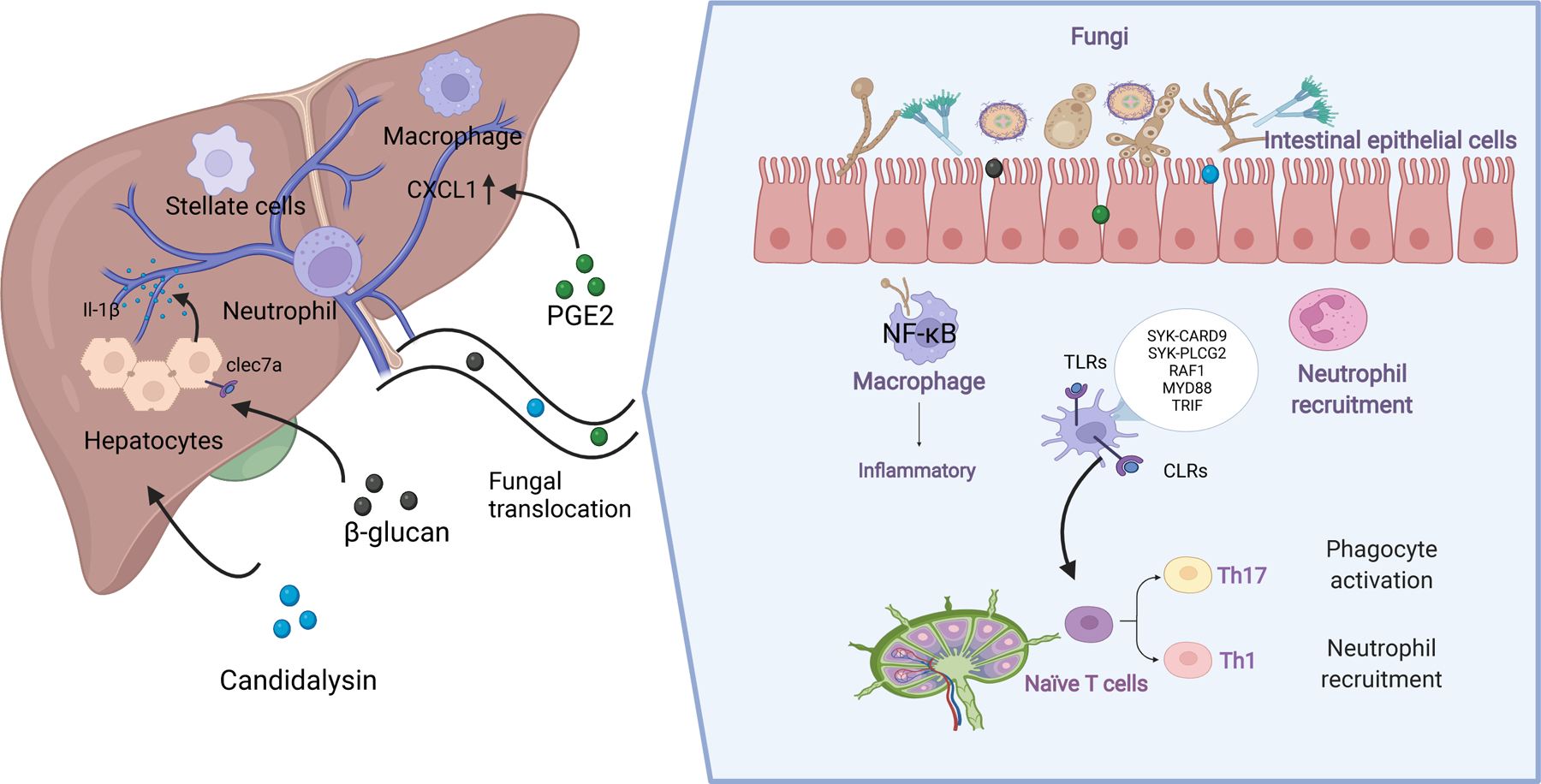

Figure 2.

The interactions between fungi and the immune system. Figures 2 was created with BioRender.com.

Interactions between fungi and intestinal immune cells maintain intestinal homeostasis by promoting a healthy composition of the mycobiota, without fungal overgrowth or species that contribute to pathological processes. The portal vein carries nutrients from the diet and products of commensal microbes to the liver. As the forefront of the defense, the intestinal barrier regulates transport of gut-derived antigens out of the intestinal mucosa and to liver. As a second firewall, the hepatic immune system helps establish tolerance towards commensal microbes and also detects fungal pathogens, preventing them from reaching the circulation. The intestinal immune system, the intestinal barrier, the liver immune system therefore form a team that maintains microbial homeostasis. When this balance is disrupted, via alterations to the intestinal immune system, dysbiosis, disrupted intestinal barrier integrity, and/or alterations to the hepatic immune response, liver diseases can develop or progress.

Myeloid immune cells such as dendritic cells, macrophages, and natural killer T cells are the first to detect alterations in the intestinal mycobiota and launch a defense against potential invaders, via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (41). Generally, there are four major types of PPRs: toll-like receptors (TLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain -like receptors (NLRs) and the galectin family proteins (galectin-3). Activation of PRRs on innate immune system cells induces an inflammatory response that clears pathogens. C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) are the main PRRs that mediate recognition of fungal pathogens. In the CLR family (dectin-1, dectin-2, DC-SIGN, CLEC4E, and the mannose receptor), dectin 1 (also called C-type lectin-like receptor or CLEC7A) is a PRR that recognizes fungi β-glucan. Compared with wildtype mice, fecal samples from CLEC7A-knockout mice have a high fungi load. However, loss of CLEC7A from bone marrow-derived cells was reported to reduce ethanol-induced steatohepatitis (17). This might be because chronic exposure of CLEC7A to fungal products such as β-glucan continuously activates the cellular inflammasome pathway, which contributes to hepatocyte damage. The PRR-induced inflammatory response should be inactivated once fungal pathogens are cleared. Continuous stimulation of PRRs results in a chronic inflammatory response that contributes to the development of liver disease.

When PPRs recognize fungal antigens, different signaling pathway can become activated; CLRs primarily activate SYK–CARD9, SYK–PLCG2, or RAF1 signaling, whereas toll-like receptors activate signaling via MYD88 or TRIF. CARD9 is an important signaling protein in the innate immune response against fungi such as yeast (42). Mice and humans with loss-of-function mutations in CARD9 are highly susceptible to fungal infections. Limon et al reported that Malassezia induces production of inflammatory cytokines and exacerbates colitis via CARD9 in mice (43). Loss of CARD9-mediated signaling prevented Malassezia restricta from exacerbating colitis in mice, although it is not clear whether these fungi contribute to pathogenesis of liver disease.

These signaling cascades from PRRs triggered by PAMP recognition can activate T-helper 1 (Th1) and/or Th17 cell-mediated responses. Th1 cell-mediated responses involve production of the cytokine interferon-gamma (IFNG), which correlates with immunity against fungi via phagocyte activation. Th17 cell-mediated responses provide defense against fungi via production of interleukin 17 (IL17) and IL22, which activates neutrophils and production of antimicrobial peptides by epithelial cells. Recent studies have shed light on how immune responses against commensal fungi can promote local and distal inflammatory diseases, especially via Th17 cells (44). The protective role of fungus-specific Th17 cells has been demonstrated not only at barrier sites but also in the circulation, where they prevent fungal overgrowth and translocation without causing overt inflammation.

Several microbes have been identified as activators of Th17 cells, including C. albicans, Malassezia spp, and Aspergillus fumigatus. C. albicans induces a strong antigen-specific Th17 cell-mediated response in humans. C. albicans-specific Th17 cells seem to be non-pathogenic but essential to prevent C. albicans overgrowth; circulating C. albicans-specific Th17 cells have been detected in healthy blood samples from healthy humans. Surprisingly, C. albicans-specific Th17 cells might broadly modulate Th17 responses against other fungi, via cross-reactivity with shared fungal epitopes. This increased antigen-target diversity is a double-edged sword, which can broaden protective immunity but also cause collateral damage to tissues. In the periphery, T cells induced by fungi may be reactivated by cross-reactive epitopes derived from local antigens (45).

Bacher et al reported that intestinal inflammation expanded C. albicans-specific and cross-reactive Th17 cells to contribute to A. fumigatus-induced (non-intestinal) lung inflammation (45). However, it is not clear whether fungus-specific T-cell and Th17-cell reactivities against these microbes are altered and contribute to development of liver disease. As mentioned above, C. albicans overgrowth has been associated with liver diseases and the frequency of IL17 cells is significantly increased in blood samples from patients with chronic liver diseases including alcohol-associated liver disease, viral hepatitis, and HCC (46–48). The IL17 receptor is expressed on almost all types of liver cells, so there is a possibility that the anti-fungal immune response could contribute to liver damage—further studies are needed.

Dysregulation of the intestinal barrier integrity allows translocation of fungal products to the liver, which might contribute to pathogenesis (49). The liver contains a diverse repertoire of myeloid and lymphoid immune cells that includes Kupffer cells, neutrophils, macrophages, natural killer cells, and T and B cells (50). When these cells are exposed to circulating fungi antigens and fungi-derived metabolites, they elicit production of inflammatory (or anti-inflammatory) cytokines and chemokines, some of which can damage the liver. The fungal cell wall polysaccharide β-glucan can induce liver inflammation via CLEC7A signaling, which leads to secretion of IL1B and hepatocyte damage (17). In addition, PGE2, a fungi-derived oxylipin generated by Meyerozyma guilliermondii, significantly increases hepatic expression of EP2, EP4, CXCL1, which contribute to the development of ethanol-induced hepatic steatosis (AHS) in mice (51).

Once the liver is not functioning properly, fungi can infect vulnerable subjects and increase the severity of liver disease. Fungal infections are diagnosed by isolation of fungi from the blood or normally sterile body fluid. Fungal infections, such as invasive candidiasis and invasive aspergillosis, are frequent in patients with cirrhosis and often trigger acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). Early diagnosis of fungal infections in patients with cirrhosis, liver transplant recipients, and patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis reduce mortality (52, 53).

Interactions Between Fungi and Bacteria.

The microbiota is a diverse ecosystem in which microbes interact with each other and with human cells. Fungi and bacteria interact chemically and physically in different niches with respect to growth, reproduction, transport/movement, nutrition, stress resistance and pathogenicity (54). In the past decade, there have been many studies of the gut microbiome, which have revealed that intestinal bacteria and their products contribute to the development of liver diseases. Dysbiosis can result in intestinal barrier dysfunction, which allows translocation of bacterial components or bacterial-derived metabolites (such as trimethylamine, secondary bile acids, short-chain fatty acids, and imidazole propionate) from gut to liver. These molecules affect systemic inflammation, energy homeostasis and, bile acid metabolism (55), which can contribute to liver disease development (Figure 1).

There are several experimental methods for studying fungal–bacterial interactions and their effects on health and disease (Figure 3). Researchers can perform simultaneous analysis (Figure 3a) of bacteria (eg.16S) and fungi (eg.18S, ITS), from the same sample, with analysis in correlation network at the different levels (family, genus). Comparing fungal–bacterial interactions between healthy and diseased samples allows for identification of microbes that differ between the samples and might be involved in pathogenesis. For example, Baja et al built correlation networks that compared linkage complexity between fecal samples from healthy individuals (controls) and patients with cirrhosis (28). The complex correlations between fungi and bacteria were called linkage patterns. Rich and complex correlations between fungi and bacteria were observed in linkage patterns of healthy controls while they were reduced to a skewed linkage pattern in patients with cirrhosis. In addition to correlation analysis of linkages, researchers can study ratios of fungi:bacteria to evaluate the network, such as the Shannon index ratio of ITS2:16S or the ratio of Bacteroidetes:Ascomycota. These types of studies help identify disruptions in the correlation network between bacteria and fungi that might contribute to liver disease progression. Lemoinne et al examined altered inter-kingdom networks in fecal samples from patients with PSC by measuring the correlation networks’ nodes, edges, and relative connectedness. The authors found that PSC was associated with an alterations of the bacteria–fungi interactions (26). Recently, fungi-bacteria correlations were analyzed in fecal samples from patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis and healthy controls, using the Sparse InversE Covariance estimation for Ecological Association and Statistical Inference. The authors found a positive association between Cladosporium and Gemmiger and a negative association between Cryptococcus and Pseudomonas in samples from patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis (21).

Figure 3.

A framework to study interactions between fungi and bacteria in the intestine.

Researchers can analyze the abundance or diversity of bacterial or fungi in fecal samples (Figure 3b), and compare communities, such as between patients who have vs have not received antibiotics or anti-fungal agents. Lang et al observed the fungal composition in fecal samples from patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis, 25% of whom had received antibiotics (18). The authors found no correlations between the abundance or diversity of fungi and treatment with antibiotics. However, antibiotic treatment was associated with higher levels of ASCA, indicating that eliminating bacteria increases the immune response against fungi. To determine whether reducing fungi in the intestine alters intestinal bacterial composition, Yang et al compared bacterial compositions of fecal samples from patients who did vs did not receive the anti-fungal agent amphotericin B (17). They found that treatment with this antifungal agent did not produce significant changes in the total numbers of bacteria or bacterial composition in fecal samples.

Another method to study interactions between intestinal bacteria and fungi involves gavage of mice with different strains and analysis of the effects (Figure 3c). Studies in animal models allow for specific manipulations that cannot be studied in humans. Germ-free mice, germ-free mice with standardized microbiota, and mice given antibiotics can be studied to determine the in vivo effects of specific combinations of bacteria and fungi. Candida spp. and Saccharomyces spp. have been the most studied fungi in these types of experiments, which have found that reductions in intestinal bacteria facilitate colonization with S. cerevisiae or C. albicans (56).

Interactions between specific fungi and bacteria can also be studied in other environments (Figure 3d). The pathologic effects of C. albicans in nematode gut can be prevented by a product of the gram-positive bacterium Enterococcus faecalis (57). When both microbes were administered to the nematodes, a bacteria-derived product inhibited hyphal morphogenesis by C. albicans. There have been recent studies of other inter-kingdom interactions, such as between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, that have relevance to human health (58). In these types of studies, the number of interacting microbes is limited, providing more direct evidence of the pathogenic and beneficial effects of specific species.

Fungal-derived metabolites

Fungi synthesize many metabolites that affect not only their own survival and replication, but also human cells. Generally, there are 4 types of fungi-derived metabolites (Figure 1): polyketides, terpenes, small peptides, and indole alkaloids. Aflatoxins and fumonisins are the most reported polyketide-derivative mycotoxins produced by fungi that grow on food, including maize, cereals, and nuts. Aflatoxins (AFB1, AFB2, AFG1 and AFG2), derived from Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus, are potent hepatocarcinogens—especially in patients with chronic HBV infection. Fumonisins. a family of mycotoxins produced by the fungi Fusarium verticillioides, have also been reported to induce hepatocellular and cholangiocellular tumors (59).

Farnesol and tyrosol are terpenes derivatives from Candida that act as quorum-sensing molecules and virulence factors (60). Farnesol affects fungi morphological transition and inhibits filamentation. Tyrosol suppress morphogenesis and stimulates the transition from spherical cells to the germ tube form. Farnesol is reported to modulate fatty acid oxidation and decrease triglyceride accumulation in steatotic HepaRG cells (61). Mohammad H Abukhalil et al reported that farnesol attenuates oxidative stress and liver injury by modulating fatty acid synthase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase in rats fed a high cholesterol-fed diet (62).

Candidalysin is a cytolytic peptide toxin secreted by opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans that can damage epithelial membranes directly and activate an immune response against them. We demonstrated that candidalysin promotes ethanol-induced liver disease in mice and that increased fecal levels of this toxin are associated with higher mortality in patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis. Furthermore, candidalysin is cytotoxic to primary hepatocytes (19).

Oxylipins (eg. 3-hydroxy eicosatetraenoic acid, prostaglandin F2α and prostaglandin E2) involved in inflammation signaling and innate and adaptive immune responses in mammalian cells(63). Recent studies reported that they can also be produced by lower eukaryotes, including yeasts and other fungi (64). Fungal oxylipins have been described to regulate immunological responses, control inflammation and immune cell maturation. Sun et al demonstrated that fungus Meyerozyma guilliermondii could generate PGE2 via transformation of arachidonic acid (51). M. guilliermondii-mediated PGE2 production in the liver promoted hepatic steatosis in mice. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis evades dendritic cell recognition by inhibiting production of PGE2 by immature dendritic cells (65). The pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans produces PGE2 that is identical to human PGE2. Fungi-derived PGE2 can act directly on Th17 cells during differentiation to inhibit IL17-dependent anti-microbial responses (66). We have characterized serum and fecal oxylipins in fecal samples from patients with alcohol-related liver disease (67). Significant alterations were observed in the serum oxylipin profile of patients with alcohol-associated liver disease and alcohol use disorder, compared to non-alcoholic controls. Fungal oxylipins may be another source for the alterations of serum and fecal oxylipin profiles. More studies are needed to connect fungal oxylipins to liver disease pathogenesis.

Fungi-based therapeutic strategies for liver disease

Although there have been interesting recent findings about how the gut mycobiota participates in development of the liver disease, there have been few, but promising, studies of potential fungal therapeutic approaches for liver disease. One approach involves the use of antifungal agents to control overgrowth in the intestine. The anti-fungal drug amphotericin B, for example, was shown to prevent ethanol-induced liver damage in mice (17) and western diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice(24). Mice that received the amphotericin B while on an ethanol diet did not develop intestinal fungal overgrowth and had lower levels of liver injury and hepatic steatosis. However, some antifungal agents have been reported to have hepatotoxic side effects.

Fungal prebiotics, such as Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii), have been tested as therapeutic agents for liver diseases. In obese mice that are models of type 2 diabetes (68), S. boulardii administration reduced hepatic steatosis and hepatic inflammation, and decreased liver markers of macrophage infiltration. In mice with different causes of liver injury, oral administration of S. boulardii increased liver function and reduced progression of liver fibrosis. In rats given CCl4 to induce liver cirrhosis, serum levels of aspartate and alanine aminotransferases and malondialdehyde decreased following administration of S. boulardii (69). Expression levels of COL1A1, αSMA, and transforming growth factor beta were also reduced in liver, indicating reductions in liver damage. Deniz Güney Duman et al (70) and Lei Yu et al (71) reported the protective effects of S. boulardii in rats with clarithromycin- and methotrexate-induced hepatic injury, and in mice with D-galactosamine-induced liver injury. Liver function tests and histopathology analyses indicated that the liver injury can be effectively attenuated by S. boulardii administration in mice.

Fungal products might also be developed as therapies. Aureobasidium pullulans (A. pullulans) secrets soluble β-glucan consisting of a β-(1,3)-linked glucose main chain and β-(1,6)-linked glucose branches. Oral administration of the A. pullulans-derived β-glucan prevented development of fatty liver in mice on high-fat diets (72). β-glucans are mainly known as immune stimulators. The potential health benefits or probiotic effects of some fungal species are known but have yet to be fully explored.

Conclusions and perspectives

There have been many recent exciting discoveries about the gut mycobiota and its role in development and progression of liver disease. These might increase our understanding of liver pathogenesis and lead to new therapeutic strategies. Despite the advances in deep sequencing-based analyses, which have shed light on the complexity of fungal communities, our understanding of how fungi contribute to or prevent pathogenesis is still at an early stage. We need continued efforts to improve methods to study gut fungi, such as improved techniques for sample collection, DNA extraction, and PCR amplification, as well as more reference databases and annotation. Gut mycobiomes vary among cohorts, and their composition is affected by factors such as patient age, sex, race, diet, nutrition, and location. Investigations of the direct and indirect factors that affect the mycobiota composition could help us identify fungi and metabolites associated with health vs disease.

Currently, most of studies are snapshots of gut mycobiomes of patients vs healthy controls. We need to move from descriptive microbiota census analyses to cause and effect studies. Joint analyses with other advanced technologies (such as metagenomics, metabolomics, and culturomics) and well-designed pharmacology and mechanistic experiments in humans, animals, and cells will provide new perspectives into disease mechanisms. More precise strategies to target specific fungi might also be developed. Bio-engineered commensals and CRISPR-Cas9 editing can be applied to edit the gut mycobiome without causing deleterious side effects. With technologic advances, we will be able to perform in-depth explorations of the gut mycobiota to learn how it maintains health and how alterations contribute to disease.

Key points.

The role of fungi (also referred to as “mycobiome”) in the pathogenesis of chronic liver diseases has not been well recognized.

We review human studies describing alterations of gut mycobiota in various types of liver diseases.

We discuss mechanisms by which fungi affect pathogenesis and disease progression, especially by the interactions with the immune system.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by NIH grants R01 AA24726, R37 AA020703, U01 AA026939, U01 AA026939-04S1, by Award Number BX004594 from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development, and a Biocodex Microbiota Foundation Grant (to B.S.) and services provided by NIH centers P30 DK120515 and P50 AA011999.

Conflicts of interest

B.S. has been consulting for Ferring Research Institute, Gelesis, HOST Therabiomics, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Mabwell Therapeutics, Patara Pharmaceuticals and Takeda. B.S.’s institution UC San Diego has received research support from Axial Biotherapeutics, BiomX, CymaBay Therapeutics, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Prodigy Biotech and Synlogic Operating Company. B.S. is founder of Nterica Bio. UC San Diego has filed several patents with B.S. as inventor related to this work.

Abbreviations

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NAFL

non-alcoholic fatty liver

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- S cerevisiae

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- M. restricta

Malassezia. restricta

- C. albicans

Candia. albicans

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

- ASCA

serum anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae IgG antibodies

- CLEC7A

C-type lectin-like receptor

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors

- CLRs

C-type lectin receptors

- galectin-3

galectin family proteins

- SYK

spleen associated tyrosine kinase

- CARD9

caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9

- PLCG2

phospholipase C gamma 2

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation primary response 88

- S. boulardii

Saccharomyces boulardii

- A. pullulans

Aureobasidium pullulans

Data Availability Statement:

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were analyzed in this study.

References

- 1.Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. 2019. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol 70:151–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2019 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999–2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

- 3.Tilg H, Cani PD, Mayer EA. 2016. Gut microbiome and liver diseases. Gut 65:2035–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert JA, Blaser MJ, Caporaso JG, Jansson JK, Lynch SV, Knight R. 2018. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nature Medicine 24:392–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huffnagle GB, Noverr MC. 2013. The emerging world of the fungal microbiome. Trends Microbiol 21:334–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauthier GM. 2017. Fungal Dimorphism and Virulence: Molecular Mechanisms for Temperature Adaptation, Immune Evasion, and In Vivo Survival. Mediators Inflamm 2017:8491383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez LR, Fries BC. 2010. Fungal Biofilms: Relevance in the Setting of Human Disease. Curr Fungal infect Rep 4:266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nobile CJ, Johnson AD. 2015. Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annu Rev Microbiol 69:71–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller NP. 2019. Fungal secondary metabolism: regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang L, Stärkel P, Fan J-G, Fouts DE, Bacher P, Schnabl B. 2021. The gut mycobiome: a novel player in chronic liver diseases. J Gastroenterol 56:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson RH, Anslan S, Bahram M, Wurzbacher C, Baldrian P, Tedersoo L. 2019. Mycobiome diversity: high-throughput sequencing and identification of fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoggard M, Vesty A, Wong G, Montgomery JM, Fourie C, Douglas RG, Biswas K, Taylor MW. 2018. Characterizing the Human Mycobiota: A Comparison of Small Subunit rRNA, ITS1, ITS2, and Large Subunit rRNA Genomic Targets. Front Microbiol. 9: 2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel R 2019. A Moldy Application of MALDI: MALDI-ToF Mass Spectrometry for Fungal Identification. J Fungi 5: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nash AK, Auchtung TA, Wong MC, Smith DP, Gesell JR, Ross MC, Stewart CJ, Metcalf GA, Muzny DM, Gibbs RA, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF. 2017. The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome 5:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallen-Adams HE, Suhr MJ. 2017. Fungi in the healthy human gastrointestinal tract. Virulence 8:352–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahnic A, Rupnik M. 2018. Different host factors are associated with patterns in bacterial and fungal gut microbiota in Slovenian healthy cohort. PLoS One 13:e0209209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang A-M, Inamine T, Hochrath K, Chen P, Wang L, Llorente C, Bluemel S, Hartmann P, Xu J, Koyama Y, Kisseleva T, Torralba MG, Moncera K, Beeri K, Chen C-S, Freese K, Hellerbrand C, Lee SM, Hoffman HM, Mehal WZ, Garcia-Tsao G, Mutlu EA, Keshavarzian A, Brown GD, Ho SB, Bataller R, Stärkel P, Fouts DE, Schnabl B. 2017. Intestinal fungi contribute to development of alcoholic liver disease. J Clin Invest 127:2829–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang S, Duan Y, Liu J, Torralba MG, Kuelbs C, Ventura-Cots M, Abraldes JG, Bosques-Padilla F, Verna EC, Brown RS Jr., Vargas V, Altamirano J, Caballería J, Shawcross D, Lucey MR, Louvet A, Mathurin P, Garcia-Tsao G, Ho SB, Tu XM, Bataller R, Stärkel P, Fouts DE, Schnabl B. 2020. Intestinal Fungal Dysbiosis and Systemic Immune Response to Fungi in Patients With Alcoholic Hepatitis. Hepatology 71:522–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu H, Duan Y, Lang S, Jiang L, Wang Y, Llorente C, Liu J, Mogavero S, Bosques-Padilla F, Abraldes JG, Vargas V, Tu XM, Yang L, Hou X, Hube B, Stärkel P, Schnabl B. 2020. The Candida albicans exotoxin candidalysin promotes alcohol-associated liver disease. J Hepatol 72:391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartmann P, Lang S, Zeng S, Duan Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Bondareva M, Kruglov A, Fouts DE, Stärkel P, Schnabl B. 2021. Dynamic Changes of the Fungal Microbiome in Alcohol Use Disorder. Front physiol 1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao B, Zhang X, Schnabl B. 2021. Fungi-Bacteria Correlation in Alcoholic Hepatitis Patients. Toxins 13:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Vigliotti C, Witjes J, Le P, Holleboom AG, Verheij J, Nieuwdorp M, Clément K. 2020. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 17:279–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demir MLS, Hartmann P, Duan Y, Martin A, Miyamoto Y, Bondareva M, Zhang XL, Wang XY, Kasper P, Bang C, Roderburg C, Tacke F, Steffen HM, Goeser T, Kroglov A, Eckmann L, Stärkel P, Fouts DE, Schnabl B 2021. The Fecal Mycobiome in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Hepatol (accepted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.You N, Xu J, Wang L, Zhuo L, Zhou J, Song Y, … & Shi J. (2021). Fecal Fungi Dysbiosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obesity 29(2): 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sirpal S, Chandok N. 2017. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: diagnostic and management challenges. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 10:265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemoinne S, Kemgang A, Belkacem KB, Straube M, Jegou S, Corpechot C, Network S-AI, Chazouillères O, Housset C, Sokol HJG. 2020. Fungi participate in the dysbiosis of gut microbiota in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut 69:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rühlemann MC, Solovjeva MEL, Zenouzi R, Liwinski T, Kummen M, Lieb W, Hov JR, Schramm C, Franke A, Bang C. 2020. Gut mycobiome of primary sclerosing cholangitis patients is characterised by an increase of Trichocladium griseum and Candida species. Gut 69:1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bajaj JS, Liu EJ, Kheradman R, Fagan A, Heuman DM, White M, Gavis EA, Hylemon P, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. 2018. Fungal dysbiosis in cirrhosis. Gut 67:1146–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krohn S, Zeller K, Böhm S, Chatzinotas A, Harms H, Hartmann J, Heidtmann A, Herber A, Kaiser T, Treuheit M, Hoffmeister A, Berg T, Engelmann C. 2018. Molecular quantification and differentiation of Candida species in biological specimens of patients with liver cirrhosis. PLoS One 13:e0197319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alqahtani SA, & Colombo M (2020). Viral hepatitis as a risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res, 6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Chen Z, Guo R, Chen N, Lu H, Huang S, Wang J, Li L. 2011. Correlation between gastrointestinal fungi and varying degrees of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 70:492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mou H, Yang F, Zhou J, Bao C. 2018. Correlation of liver function with intestinal flora, vitamin deficiency and IL-17A in patients with liver cirrhosis. Exp Ther Med 16:4082–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo R, Chen Z, Chen N, Chen Y. 2010. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of Intestinal Regular Fungal Species in Fecal Samples From Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Lab Med 41:591–596. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mashaly GE-S, El-Sabbagh AM, Sheta TF. 2017. GI Tract Mycobiome in Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Case Control Study. Egypt J Med Microbiol 38:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. 2021. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magnussen A, Parsi MA. 2013. Aflatoxins, hepatocellular carcinoma and public health. World J Gastroenterol 19:1508–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian GS, Ross RK, Yu MC, Yuan JM, Gao YT, Henderson BE, Wogan GN, Groopman JD. 1994. A follow-up study of urinary markers of aflatoxin exposure and liver cancer risk in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 3:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long X-D, Yao J-G, Huang Y-Z, Huang X-Y, Ban F-Z, Yao L-M, Fan L-D. 2011. DNA repair gene XRCC7 polymorphisms (rs#7003908 and rs#10109984) and hepatocellular carcinoma related to AFB1 exposure among Guangxi population, China. Hepatol Res 41:1085–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Lu D, Zhuo J, Lin Z, Yang M, Xu X. 2020. The Gut-liver Axis in Immune Remodeling: New insight into Liver Diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci 16:2357–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arab JP, Martin-Mateos RM, Shah VH. 2018. Gut-liver axis, cirrhosis and portal hypertension: the chicken and the egg. Hepatol Int 12:24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romani L 2011. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol 11:275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glocker E-O, Hennigs A, Nabavi M, Schäffer AA, Woellner C, Salzer U, Pfeifer D, Veelken H, Warnatz K, Tahami F, Jamal S, Manguiat A, Rezaei N, Amirzargar AA, Plebani A, Hannesschläger N, Gross O, Ruland J, Grimbacher B. 2009. A Homozygous CARD9 Mutation in a Family with Susceptibility to Fungal Infections. N Engl J Med 361:1727–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Limon JJ, Tang J, Li D, Wolf AJ, Michelsen KS, Funari V, Gargus M, Nguyen C, Sharma P, Maymi VI, Iliev ID, Skalski JH, Brown J, Landers C, Borneman J, Braun J, Targan SR, McGovern DPB, Underhill DM. 2019. Malassezia Is Associated with Crohn’s Disease and Exacerbates Colitis in Mouse Models. Cell Host Microbe 25:377–388.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheffold A, Bacher P, LeibundGut-Landmann S. 2020. T cell immunity to commensal fungi. Curr Opin Microbiol 58:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bacher P, Hohnstein T, Beerbaum E, Röcker M, Blango MG, Kaufmann S, Röhmel J, Eschenhagen P, Grehn C, Seidel K, Rickerts V, Lozza L, Stervbo U, Nienen M, Babel N, Milleck J, Assenmacher M, Cornely OA, Ziegler M, Wisplinghoff H, Heine G, Worm M, Siegmund B, Maul J, Creutz P, Tabeling C, Ruwwe-Glösenkamp C, Sander LE, Knosalla C, Brunke S, Hube B, Kniemeyer O, Brakhage AA, Schwarz C, Scheffold A. 2019. Human Anti-fungal Th17 Immunity and Pathology Rely on Cross-Reactivity against Candida albicans. Cell 176:1340–1355.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chackelevicius CM, Gambaro SE, Tiribelli C, Rosso N. 2016. Th17 involvement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 22:9096–9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hammerich L, Heymann F, Tacke F. 2011. Role of IL-17 and Th17 cells in liver diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 2011:345803–345803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lafdil F, Miller AM, Ki SH, Gao B. 2010. Th17 cells and their associated cytokines in liver diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 7:250–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicoletti A, Ponziani FR, Biolato M, Valenza V, Marrone G, Sganga G, Gasbarrini A, Miele L, Grieco A. 2019. Intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of liver damage: From non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 25:4814–4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heymann F, Tacke F. 2016. Immunology in the liver-from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13:88–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun S, Wang K, Sun L, Cheng B, Qiao S, Dai H, Shi W, Ma J, Liu H. 2020. Therapeutic manipulation of gut microbiota by polysaccharides of Wolfiporia cocos reveals the contribution of the gut fungi-induced PGE(2) to alcoholic hepatic steatosis. Gut microbes 12:1830693–1830693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernández J, Piano S, Bartoletti M, Wey EQ. 2021. Management of bacterial and fungal infections in cirrhosis: The MDRO challenge. J Hepatol 75:S101–S117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alexopoulou A, Vasilieva L, Agiasotelli D, Dourakis SP. 2015. Fungal infections in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 63:1043–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krüger W, Vielreicher S, Kapitan M, Jacobsen ID, Niemiec MJ. 2019. Fungal-Bacterial Interactions in Health and Disease. Pathogens 8:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang L, Schnabl B. 2020. Gut Microbiota in Liver Disease: What Do We Know and What Do We Not Know? Physiology 35:261–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang TT, Shao TY, Ang WXG, Kinder JM, Turner LH, Pham G, Whitt J, Alenghat T, Way SS. 2017. Commensal Fungi Recapitulate the Protective Benefits of Intestinal Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 22:809–816.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garsin DA, Lorenz MC. 2013. Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis in the gut: synergy in commensalism? Gut Microbes 4:409–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peleg AY, Hogan DA, Mylonakis E. 2010. Medically important bacterial–fungal interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 8:340–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lemmer ER, Vessey CJ, Gelderblom WC, Shephard EG, Van Schalkwyk DJ, Van Wijk RA, Marasas WF, Kirsch RE, Hall Pde L. 2004. Fumonisin B1-induced hepatocellular and cholangiocellular tumors in male Fischer 344 rats: potentiating effects of 2-acetylaminofluorene on oval cell proliferation and neoplastic development in a discontinued feeding study. Carcinogenesis 25:1257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albuquerque P, Casadevall A. 2012. Quorum sensing in fungi--a review. Med Mycol 50:337–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pant A, Rondini EA, Kocarek TA. 2019. Farnesol induces fatty acid oxidation and decreases triglyceride accumulation in steatotic HepaRG cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 365:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abukhalil MH, Hussein OE, Bin-Jumah M, Saghir SAM, Germoush MO, Elgebaly HA, Mosa NM, Hamad I, Qarmush MM, Hassanein EM, Kamel EM, Hernandez-Bautista R, Mahmoud AM. 2020. Farnesol attenuates oxidative stress and liver injury and modulates fatty acid synthase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase in high cholesterol-fed rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 27:30118–30132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawahara K, Hohjoh H, Inazumi T, Tsuchiya S, Sugimoto Y. 2015. Prostaglandin E2-induced inflammation: Relevance of prostaglandin E receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851:414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tan TG, Lim YS, Tan A, Leong R, Pavelka N. 2019. Fungal Symbionts Produce Prostaglandin E2 to Promote Their Intestinal Colonization. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 9:359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fernandes RK, Bachiega TF, Rodrigues DR, Golim MdA, Dias-Melicio LA, Balderramas HdA, Kaneno R, Soares AMVC. 2015. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis interferes on dendritic cells maturation by inhibiting PGE2 production. PloS one 10:e0120948–e0120948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valdez PA, Vithayathil PJ, Janelsins BM, Shaffer AL, Williamson PR, Datta SK. 2012. Prostaglandin E2 suppresses antifungal immunity by inhibiting interferon regulatory factor 4 function and interleukin-17 expression in T cells. Immunity 36:668–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gao B, Lang S, Duan Y, Wang Y, Shawcross DL, Louvet A, Mathurin P, Ho SB, Stärkel P, Schnabl B. 2019. Serum and Fecal Oxylipins in Patients with Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. Dig Dis Sci 64:1878–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Everard A, Matamoros S, Geurts L, Delzenne NM, Cani PD. 2014. Saccharomyces boulardii administration changes gut microbiota and reduces hepatic steatosis, low-grade inflammation, and fat mass in obese and type 2 diabetic db/db mice. mBio 5:e01011–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li M, Zhu L, Xie A, Yuan J. 2015. Oral administration of Saccharomyces boulardii ameliorates carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats via reducing intestinal permeability and modulating gut microbial composition. Inflammation 38:170–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duman D, Özdemir ZN, Ercan F, Deniz M, Can G, Yeğen B. 2013. Saccharomyces boulardii ameliorates clarithromycin-and methotrexate-induced intestinal and hepatic injury in rats. Br. J. Nutr 110:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu L, Zhao X-K, Cheng M-L, Yang G-Z, Wang B, Liu H-J, Hu Y-X, Zhu L-L, Zhang S, Xiao Z-W, Liu Y-M, Zhang B-F, Mu M. 2017. Saccharomyces boulardii Administration Changes Gut Microbiota and Attenuates D-Galactosamine-Induced Liver Injury. Sci Rep 7:1359–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Muramatsu D, Okabe M, Takaoka A, Kida H, Iwai A. 2017. Aureobasidium pullulans produced β-glucan is effective to enhance Kurosengoku soybean extract induced Thrombospondin-1 expression. Sci Rep 7:2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were analyzed in this study.