Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance was characterized for 14 strains of Streptococcus mitis. HinfI restriction fragment length mapping of gyrA PCR amplicons from three ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates correlated with mutations associated with such resistance in other organisms. By using PCR, seven erythromycin-resistant strains were found to possess either the mef or ermB gene. Hybridization revealed tet(M) in seven tetracycline-resistant isolates.

The emergence of multidrug resistance has been observed in viridans group streptococci (4, 7). A 36-year-old woman with a history of common variable immunodeficiency was diagnosed with recurrent septicemia, secondary to cellulitis, caused by multidrug-resistant viridans group streptococci. In this study, two strains of viridans group streptococci, isolated from blood taken from this patient, were compared with other clinical blood culture isolates of viridans group streptococci collected in the Toronto region in terms of epidemiological relationship, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, and mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance.

(This work was presented in part at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, September 1997 [15].)

Isolates.

The two case viridans group streptococci, isolated from blood cultures collected in May and June 1996, were identified as Streptococcus mitis. They were compared to 12 other clinical S. mitis blood culture isolates that were selected, on the basis of the diversity of their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, from 1991 to 1994 laboratory records from three Toronto hospitals. All S. mitis strains were identified by conventional methods (2). The organisms had been stored at −70°C and were subcultured twice before testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Broth microdilution and/or macrodilution testing of each isolate was performed according to the protocols of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (10). Agents tested included the following: ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, penicillin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, imipenem, and vancomycin.

PFGE.

Relatedness of the S. mitis strains was determined by SmaI pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) by using a modification of the method of Murray et al. (9), which included the addition of mutanolysin (Sigma Chemical Co., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) to the lysis buffer. PFGE parameters were 175 V for 20 h at 12°C, and ramped pulse times were from 5 to 60 s.

PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.

Amplifications were performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 (Perkin Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) with 20 pmol of each primer, 6 nmol of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1 U of Taq polymerase per 50-μl reaction mixture. Previously characterized Streptococcus pneumoniae or Staphylococcus aureus strains were used as positive and negative controls. Primers based on homologous regions of the gyrA genes of S. pneumoniae (GenBank accession no. X95718) and S. aureus (GenBank accession no. M37915) were designed to include the single HinfI site previously shown to be useful for restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis in other organisms (13, 16). The forward primer was 5′-CGTCGCATTCTCTACGGAATGAATGA-3′ (corresponding to S. aureus gyrA nucleotides 139 to 164), and the reverse primer was 5′-TGCTCA TACGTGCCTCGGTATAACG-3′ (corresponding to S. aureus gyrA nucleotides 388 to 364), yielding a 250-bp product. HinfI digestion of this product was expected to result in 109- and 141-bp fragments, if the expected HinfI site remained intact. Reaction conditions were one cycle at 94°C for 4 min; 50 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s; and one cycle at 72°C for 10 min. Amplicons were digested with HinfI and resolved on a 3% low-melting-temperature agarose gel (NuSieve GTG Agarose; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine). Amplification of mef and ermB genes (17) was performed under the following conditions: one cycle at 94°C for 4 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s; and one cycle at 72°C for 10 min. Expected products were 348 and 639 bp, respectively.

Southern blot analysis.

DNA-DNA hybridization was used to detect the tet(M) gene. DNA from the PFGE gel was transferred to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). The tet(M) probe was generated by PCR by using T3 and T7 primers and plasmid pRN6680 which contains the tet(M) gene (11) (kindly provided by B. Kreiswirth, Public Health Research Institute, New York, N.Y.) as a template. The probe was labelled, and tet(M) was detected by using the ECL direct nucleic acid labelling and detection system (Amersham Life Science), a system based on the principle of enhanced chemiluminescence.

Results and discussion.

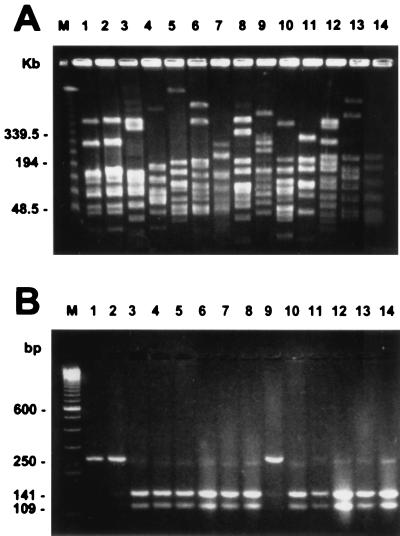

The two case S. mitis isolates were indistinguishable from each other by PFGE but could be distinguished from the noncase S. mitis isolates which were genetically distinct (Fig. 1). Both case isolates were multidrug-resistant, and the 12 noncase isolates had a variety of resistance patterns (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Results of SmaI PFGE (A) and HinfI digestion of 250-bp gyrA PCR amplicons (B) of the 14 S. mitis isolates. Lanes 1 and 2, S. mitis strains isolated from the case patient in April and May 1996, respectively; lanes 3 through 14, 12 noncase S. mitis isolates. Lanes M, Lamba Ladder PFG marker (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) (A) and the 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) (B).

TABLE 1.

Results of in vitro susceptibility testing and molecular characterization of the 14 S. mitis isolates

| Isolate | MIC (μg/ml)a of:

|

Molecular characterization by:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | ERY | CLI | TET | PEN | CTX | CRO | IMP | VAN | PCR

|

tet(M)d hybridization | |||

| gyrAb | mefc | ermBc | |||||||||||

| Case | |||||||||||||

| April 1996 | 64 | >32 | >16 | >16 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + |

| May 1996 | 64 | >32 | >16 | >16 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | + | − | + | + |

| Noncase | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.5 | >8 | >8 | ≤0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.06 | ≤0.5 | − | − | + | − |

| 2 | 0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | >4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.5 | − | − | − | + |

| 3 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | >4 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | ≤0.5 | − | − | − | + |

| 4 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | ≤0.5 | − | − | − | − |

| 5 | 2 | >8 | >8 | ≤0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.06 | ≤0.5 | − | − | + | − |

| 6 | 0.5 | 1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | ≤0.5 | − | + | − | − |

| 7 | 64 | >8 | >8 | >4 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.5 | + | − | + | + |

| 8 | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | ≤0.5 | − | + | − | − |

| 9 | 4 | >8 | >8 | >4 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.06 | ≤0.5 | − | − | + | + |

| 10 | 1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 0.03 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | 0.03 | ≤0.5 | − | − | − | − |

| 11 | 0.5 | >8 | >8 | >4 | >8 | >4 | >4 | 2 | ≤0.5 | − | − | + | + |

| 12 | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ≤0.5 | − | + | − | − |

CIP, ciprofloxacin; ERY, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin; TET, tetracycline; PEN, penicillin; CTX, cefotaxime; CRO, ceftriaxone; IMP, imipenem; VAN, vancomycin.

gyrA PCR amplicons (250 bp) were digested by HinfI. +, failure to cleave at the expected HinfI site; −, cleavage at the expected HinfI site resulting in 109- and 141-bp fragments.

Amplification of mef and ermB genes was performed by using PCR. +, presence of the amplicon; −, absence of the amplicon.

Southern blot hybridization was used to detect the tet(M) gene. +, presence of tet(M); −, absence of tet(M).

Literature describing molecular mechanisms conferring resistance in viridans group streptococci is limited; to our knowledge, only one published report that focuses on this issue exists (1). In our study, the molecular characterization of the case multidrug-resistant strains of S. mitis as well as the 12 noncase clinical S. mitis isolates revealed a number of novel findings (Table 1).

Quinolone resistance in gram-positive bacteria has been associated with alterations of the DNA gyrase gene (gyrA and/or gyrB), alterations of the topoisomerase IV gene (parC and/or parE), and/or the enhanced efflux of the antimicrobial. In S. pneumoniae and S. aureus, mutations in the gyrA gene that confer high-level quinolone resistance have been shown to occur at residues equivalent to serine 84 in S. aureus; the nucleotide sequence near this serine codon forms a HinfI site that is eliminated by resistance mutations (13, 16). In this study, gyrA amplicons from three highly ciprofloxacin-resistant strains were not susceptible to HinfI digestion, whereas gyrA amplicons from 11 isolates with ciprofloxacin susceptibility or low-level resistance were cut by HinfI into 109- and 141-bp fragments (Fig. 1). These results suggest that a mutation(s) similar to those that exist in S. pneumoniae and S. aureus also exists in viridans group streptococci. To our knowledge, this has not been documented previously. Sequencing the gyrA amplicons in order to define the precise mutations that correlate to quinolone resistance would be of interest.

Macrolide resistance in gram-positive bacteria has been associated with the mef and ermB genes. The mef gene encodes a macrolide efflux system (17). The ermB gene encodes a 23S-rRNA methylase that prevents the binding of macrolides, lincosamides, and the type B streptogramins to affected ribosomes, thereby conferring macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance constitutively or inducibly, with low levels of erythromycin being the most effective inducer (6). In this study, the mef gene was found in three S. mitis isolates displaying erythromycin resistance and clindamycin susceptibility; in these isolates, clindamycin resistance was not inducible by exposure to erythromycin, as tested by the method of Jenssen et al. (6). Seven isolates with erythromycin and clindamycin resistance were found to possess the ermB gene. Although the ermB gene has previously been found in viridans group streptococci (1), the mef gene has not.

Tetracycline resistance in gram-positive bacteria has been associated with different tetracycline resistance determinants which confer resistance by various mechanisms. For example, tet(L) decreases tetracycline uptake by an energy-dependent efflux system (8), while tet(M) inhibits the effects of tetracycline by mediating the release of ribosome-bound tetracycline in a reaction dependent on GTP (3). In this study, only tet(M) was investigated. Hybridization revealed that all seven tetracycline-resistant S. mitis strains possessed tet(M); this has been documented previously in tetracycline-resistant Streptococcus anginosus (1) and Streptococcus intermedius (12).

The documentation of these mechanisms is not only important for the understanding of antimicrobial resistance in viridans group streptococci but also has a more general significance among other streptococcal species, given the potential for both horizontal and vertical gene transfers (5, 14). Viridans group streptococci represent a significant component of human commensal flora. Particularly where exposure to antimicrobial pressure is high, as was seen in the case patient, selection of resistant viridans group streptococci may occur, and thereafter, resistance determinants may be transferred to S. pneumoniae and other species.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Bacterial Diseases Network.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clermont D, Horaud T. Identification of chromosomal antibiotic resistance genes in Streptococcus anginosus (“S. milleri”) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1685–1690. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coykendall A L. Classification and identification of the viridans streptococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:315–328. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dantley K A, Burdett V. Abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Tet(M)-mediated tetracycline resistance: requirement for tet(M)-ribosome association, abstr. C-112; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doern G V, Ferraro M J, Brueggemann A B, Ruoff K L. Emergence of high rates of antimicrobial resistance among viridans group streptococci in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:891–894. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Woodford N, Johnson A P, George R C, Spratt B G. Penicillin-resistant viridans streptococci have obtained altered penicillin-binding protein genes from penicillin-resistant strains of Streptococci pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5858–5862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenssen W D, Thakker-Varia S, Dubin D T, Weinstein M P. Prevalence of macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramin B resistance and erm gene classes among clinical strains of staphylococci and streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:883–888. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.6.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacMillan L, Willey B M, Degani O, Matlow A, Low D E, McGeer A J. Abstracts of the 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. Characterization and susceptibilities of Toronto blood culture isolates of the viridans streptococci, abstr. E-49; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMurry L M, Park B H, Burdett V, Levy S B. Energy-dependent efflux mediated by class L (TetL) tetracycline resistance determinant from streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1648–1650. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.10.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray B E, Singh K V, Heath J D, Sharma B R, Weinstock G M. Comparison of genomic DNAs of different enterococcal isolates using restriction endonucleases with infrequent recognition sites. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2059–2063. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2059-2063.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Document M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nesin M, Svec P, Lupski J R, Godson G N, Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Projan S J. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of a chromosomally encoded tetracycline resistance determinant, tetA(M), from a pathogenic, methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2273–2276. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsvik B, Olsen I, Tenover F C. Detection of tet(M) and tet(O) using the polymerase chain reaction in bacteria isolated from patients with periodontal disease. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10:87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1995.tb00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan X, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potgieter E, Chalkley L J. Reciprocal transfer of penicillin resistance genes between Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus mitior and Streptococcus sanguis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;28:463–465. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poutanen S M, de Azavedo J, Willey B M, Low D E, MacDonald K S. Abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Multi-resistant Streptococcus mitis causing recurrent septicemia in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency: case report and mechanisms of resistance, abstr. C-78; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sreedharan S, Pereson L R, Fisher L M. Ciprofloxacin resistance in coagulase-positive and -negative staphylococci: role of mutations at serine 84 in the DNA gyrase A protein of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2151–2154. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.10.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]