Abstract

The family Conidae, commonly known as cone snails, is one of the most intriguing gastropod groups owing to their diverse array of feeding behaviors (diets) and toxin peptides (conotoxins). Conuslischkeanus Weinkauff, 1875 is a worm-hunting species widely distributed from Africa to the Northwest Pacific. In this study, we report the mitochondrial genome sequence of C.lischkeanus and inferred its phylogenetic relationship with other Conus species. Its mitochondrial genome is a circular DNA molecule (16,120 bp in size) composed of 37 genes: 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA genes, and two ribosomal RNA genes. Phylogenetic analyses of concatenated nucleotide sequences of 13 PCGs and two ribosomal RNA genes showed that C.lischkeanus belongs to the subgenus Lividoconus group, which is grouped with species of the subgenus Virgiconus, and a member of the largest assemblage of worm-hunting (vermivorous) species at the most basal position in this group. Mitochondrial genome phylogeny supports the previous hypothesis that the ancestral diet of cone snails was worm-hunting, and that other dietary types (molluscivous or piscivorous) have secondarily evolved multiple times from different origins. This new, complete mitochondrial genome information provides valuable insights into the mitochondrial genome diversity and molecular phylogeny of Conus species.

Keywords: Cone snail, dietary type evolution, Lividoconus

Introduction

The genus Conus Linnaeus, 1758 is a well-known predatory gastropod group that produces venomous peptides, called conotoxins, to capture prey and defend against predators (Dutertre et al. 2004; Prashanth et al. 2016; Kohn 2019). There are more than 750 Conus species reported worldwide (WoRMS 2021), which are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical ocean areas in various environments ranging from deep water to the intertidal zone (Kohn 1959). With the notable exception of a few conid species that prey on more than one dietary type (e.g., Californiconuscalifornicus (Reeve, 1844) and Conusbullatus Linnaeus, 1758), most species in this genus show a very narrow range of prey, feeding on worms, mollusks, and fishes, and they are grouped into three specialized dietary types according to their prey types: vermivorous (worm-hunting), molluscivorous (mollusk-hunting), and piscivorous (fish-hunting) (Duda Jr et al. 2001; Olivera et al. 2014; Robinson et al. 2014; Himaya et al. 2015; Gao et al. 2018). Among these diverse dietary types, the worm-hunting diet is the most common, accounting for more than 70% of the species, and it is widely considered the most ancestral; other dietary types are regarded to have undergone secondary evolution (Duda Jr et al. 2001; Puillandre et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2018; Abalde et al. 2019). The evolutionary origin and diversification of their dietary specification can be better understood based on well-reconstructed phylogenetic relationships among Conus species of different diet types.

The implementation of new sequencing technologies (e.g., next-generation sequencing; NGS) and various bioinformatics tools has allowed mitochondrial genome sequencing to be markedly easier, cost-effective, and widely used for studying phylogeny in various metazoan groups, including Conus species (Abalde et al. 2017; Uribe et al. 2017, 2018). As of January 2022, complete and partial mitochondrial genome sequences of 60 Conus species have been reported in GenBank, most of which are tropical and subtropical species, and diverse species in other oceanic regions are relatively underrepresented. To elucidate the phylogenetic relationships and evolution of dietary specialization within the genus, phylogenetic analysis using additional mitochondrial genome information sampled from various regional species is needed. To date, only partial mitochondrial gene sequences (12S, 16S, and cox1) of Conuslischkeanus are currently available on GenBank, with no complete mitochondrial genome information for this species. Conuslischkeanus Weinkauff, 1875 is a vermivorous species reported from East Africa to the western Pacific (Röckel et al. 1995). In this study, we determine the complete mitochondrial genome of C.lischkeanus for the first time and perform a phylogenetic analysis of 13 protein-coding genes and two ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequences of 39 Conus species with different dietary types, including C.lischkeanus.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

Conuslischkeanus specimen was collected from Moonseom, Jeju Island, Korea, preserved in 95% ethanol solution, and deposited in the Marine Mollusk Resource Bank of Korea (MMRBK; voucher specimen no. MMRBK6746) in Seoul, Korea. The specimen was morphologically identified based on shell characters, which include a conical last whorl covered with yellow-brown periostracum and an angular shoulder. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the foot tissue using an E.Z.N.A. mollusc DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

NGS and mitochondrial genome assembly and annotation

Whole-genome sequencing libraries were prepared using the MGIEasy DNA library prep kit (BGI, Shenzhen, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using the QuantiFluor ssDNA System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). Sequencing was conducted on the MGISEQ-2000 system with 150 base-pair reads. A total of 48,608,637 raw reads were obtained, and adapter-trimmed using a skewer program (Jiang et al. 2014) with a mean quality threshold of 20. The mitochondrial genome was assembled from trimmed reads using MITObim v. 1.9.1 (Hahn et al. 2013). Mitochondrial gene annotation was performed using MITOS websever (Bernt et al. 2013) and confirmed through sequence comparison with mitochondrial genomes of other Conus species previously reported (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2008; Cunha et al. 2009; Brauer et al. 2012; Barghi et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016a, 2016b, 2016c; Gao et al. 2018; Uribe et al. 2018) using Geneious v. 9.1.8 (Kearse et al. 2012). The nucleotide composition, amino acid composition, and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) were analyzed using the MEGA X program (Kumar et al. 2018). Nucleotide composition skew was calculated using the following formula: AT-skew = [A – T] / [A + T] and GC-skew = [G – C] / [G + C] (Perna and Kocher 1995).

Phylogenetic analysis

To determine the relationship between C.lischkeanus and other Conus species, phylogenetic analyses were performed for the nucleotide sequences of 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs) and two rRNA genes from 39 complete or nearly complete mitochondrial genomes of the family Conidae (Table 1). Tomopleura sp., belonging to the family Borsoniidae, was also included as an outgroup in the analysis. A concatenated nucleotide sequence dataset (13,870 bp long) of the 13 PCGs and two rRNA genes was prepared for phylogenetic analysis. The best substitution model for each gene was estimated using jModelTest v. 2.1.10 (Darriba et al. 2012) with the Akaike information criterion (AIC) for the nucleotide dataset. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. ML analysis was performed using RAxML v. 8.2.9 (Stamatakis 2014) with a heuristic search and 10,000 bootstrap replicates. The BI tree was generated using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method, with two independent runs of 1 × 106 generations with four chains, sampling every 100 generations and discarding the first 25% generations as burn-in. Both ML and BI programs were conducted using the CIPRES portal (Miller et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Complete mitochondrial genomes used for phylogenetic analysis in this study.

| Family | Species | Diet | GenBank | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conidae | Conusvictoriae | Molluscivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 |

| Conusgloriamaris | Molluscivorous | KU996360 | — | |

| Conustextile | Molluscivorous | DQ862058 | Bandyopadhyay et al. 2008 | |

| Conusepiscopatus | Molluscivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusmarmoreus | Molluscivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusnobilis | Molluscivorous | KX263253 | Uribe et al. 2017 | |

| Conusermineus | Piscivorous | KY864977 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conustulipa | Piscivorous | KR006970 | Chen et al. 2016a | |

| Conusconsors | Piscivorous | KF887950 | Brauer et al. 2012 | |

| Conusstriatus | Piscivorous | KX156937 | Chen et al. 2016b | |

| Conusbetulinus | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conussponsalis | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusarenatus | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusgoudeyi | Vermivorous | KY864975 | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusebraeus | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conuscoronatus | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusmiliaris | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conuspseudonivifer | Vermivorous | KY864969 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conusvenulatus | Vermivorous | KX263250 | Uribe et al. 2017 | |

| Conusateralbus | Vermivorous | KY864970 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conusbyssinus | Vermivorous | KY864973 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conuspulcher | Vermivorous | KY864972 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conusgenuanus | Vermivorous | KY864974 | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conushybridus | Vermivorous | KX263252 | Uribe et al. 2017 | |

| Conusguanche | Vermivorous | KY801847 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conusventricosus | Vermivorous | KX263251 | Uribe et al. 2017 | |

| Conusmiruchae | Vermivorous | KY864971 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conusborgesi | Vermivorous | EU827198 | Cunha et al. 2009 | |

| Conusinfinitus | Vermivorous | KY864967 | Abalde et al. 2017 | |

| Conusspurius | Vermivorous | KY864976 | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusvirgo | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conusquercinus | Vermivorous | KY609509 | Gao et al. 2018 | |

| Conuslischkeanus | Vermivorous | OL632021 | This study | |

| Conuslividus | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conustabidus | Vermivorous | KY864968 | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conuslenavati | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conustribblei | Vermivorous | KT199301 | Barghi et al. 2016 | |

| Conusimperialis | Vermivorous | — | Abalde et al. 2019 | |

| Conuscapitaneus | Vermivorous | KX155573 | Chen et al. 2016c | |

| Conasprellawakayamaensis | Vermivorous | KX263254 | Uribe et al. 2017 | |

| Californiconuscalifornicus | All | KX263249 | Uribe et al. 2017 | |

| Profundiconusteramachii | Vermivorous | KX263256 | Uribe et al. 2017 | |

| Borsoniidae | Tomopleura sp. | — | KX263259 | Uribe et al. 2017 |

Results and discussion

Mitochondrial genome organization and nucleotide composition

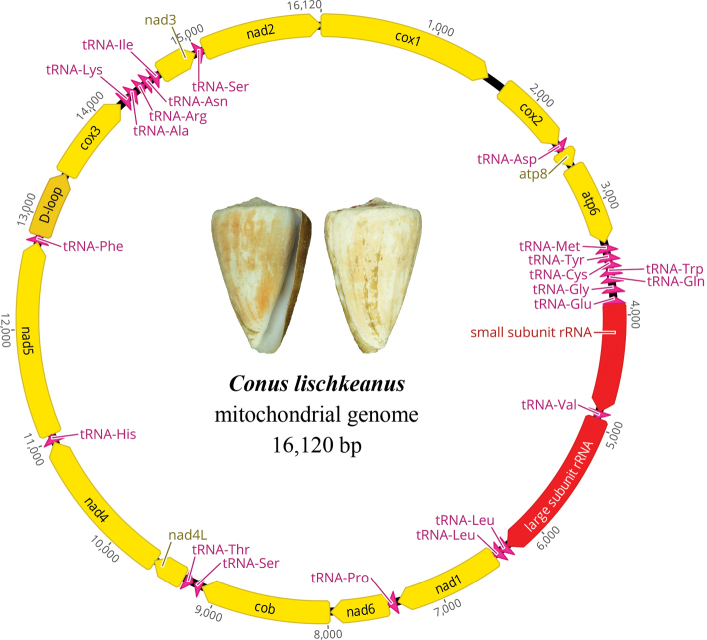

Conuslischkeanus is widely distributed from East Africa to the western Pacific (Röckel et al. 1995), extending to Taiwan, Japan, and Korea (Jeju Island). This species shows a wide range of shell morph and color variations, depending on geographic origin, which were previously classified as a few separate subspecies (Coomans and Filmer 1985) but are now treated as local variations of C.lischkeanus (Röckel et al. 1995). In this study, we determine the complete mitochondrial genome of C.lischkeanus and compare it with other cone snail species to infer the evolutionary diversification of different dietary types. The complete mitochondrial genome of C.lischkeanus (GenBank accession number: OL632021) is 16,120 bp in size, encoding 13 PCGs, 22 tRNA genes, two rRNA genes, and one control region (Fig. 1, Table 2). The overall nucleotide base composition is 29% A, 37.1% T, 17.6% G, and 16.3% C (Table 3). All 13 PCGs, 14 tRNAs, and two rRNA genes are encoded on the heavy strand, whereas eight tRNA genes (trnT, trnM, trnY, trnC, trnW, trnQ, trnG, and trnE) are encoded on the light strand. The gene order is identical to that of other cone snail species, suggesting that the mitochondrial gene order of this genus is highly conserved (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2008; Cunha et al. 2009; Brauer et al. 2012; Barghi et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016a, 2016b, 2016c; Gao et al. 2018; Uribe et al. 2018). The AT and GC-skew values of the entire genome sequences, which represent the measures of compositional asymmetry, were negative (−0.1233) and positive (0.0390), respectively, similar to those of cone snails (Gao et al. 2018).

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial genome structure of Conuslischkeanus.

Table 2.

Gene regions in the mitochondrial genome of Conuslischkeanus.

| Gene | Start | Stop | Strand direction | Length (bp) | Codon (start) | Codon (stop) | Overlapping regions | Intergenic spacers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cox1 | 1 | 1,548 | H | 1,548 | ATG | TAA | 1 | 166 |

| cox2 | 1,715 | 2,401 | H | 687 | ATG | TAA | — | — |

| tRNA-Asp (trnD) (gtc) | 2,402 | 2,468 | H | 67 | — | — | ||

| atp8 | 2,469 | 2,630 | H | 162 | ATG | TAA | — | 6 |

| atp6 | 2,637 | 3,359 | H | 723 | ATG | TAA | — | 11 |

| tRNA-Met (trnM) (cat) | 3,371 | 3,438 | L | 68 | — | 12 | ||

| tRNA-Tyr (trnY) (gta) | 3,451 | 3,516 | L | 66 | — | 1 | ||

| tRNA-Cys (trnC) (gca) | 3,518 | 3,582 | L | 65 | — | — | ||

| tRNA-Trp (trnW) (tca) | 3,583 | 3,648 | L | 66 | — | — | ||

| tRNA-Gln (trnQ) (ttg) | 3,646 | 3,711 | L | 66 | 3 | 24 | ||

| tRNA-Gly (trnG) (tcc) | 3,736 | 3,802 | L | 67 | — | 35 | ||

| tRNA-Glu (trnE) (ttc) | 3,838 | 3,902 | L | 65 | — | — | ||

| small subunit rRNA (rrnS) | 3,903 | 4,854 | H | 952 | — | — | ||

| tRNA-Val (trnV) (tac) | 4,855 | 4,921 | H | 67 | — | — | ||

| large subunit rRNA (rrnL) | 4,922 | 6,296 | H | 1,375 | — | — | ||

| tRNA-Leu1 (trnL1) (tag) | 6,297 | 6,366 | H | 70 | — | 6 | ||

| tRNA-Leu2 (trnL2) (taa) | 6,373 | 6,441 | H | 69 | — | — | ||

| nad1 | 6,442 | 7,383 | H | 942 | ATG | TAG | — | 16 |

| tRNA-Pro (trnP) (tgg) | 7,400 | 7,468 | H | 69 | — | — | ||

| nad6 | 7,469 | 7,975 | H | 507 | ATG | TAA | — | 13 |

| cob | 7,989 | 9,128 | H | 1,140 | ATG | TAA | — | 11 |

| tRNA-Ser2 (trnS2) (tga) | 9,140 | 9,204 | H | 65 | — | 16 | ||

| tRNA-Thr (trnT) (tgt) | 9,221 | 9,289 | L | 69 | — | 22 | ||

| nad4L | 9,312 | 9,608 | H | 297 | ATG | TAG | — | — |

| nad4 | 9,602 | 10,984 | H | 1,383 | ATG | TAG | 7 | — |

| tRNA-His (trnH) (gtg) | 10,984 | 11,049 | H | 66 | 1 | — | ||

| nad5 | 11,050 | 12,765 | H | 1,716 | ATG | TAA | — | — |

| tRNA-Phe (trnF) (gaa) | 12,765 | 12,829 | H | 65 | 1 | — | ||

| D-loop | 12,830 | 13,415 | H | 586 | — | — | ||

| cox3 | 13,416 | 14,195 | H | 780 | ATG | TAA | — | 34 |

| tRNA-Lys (trnK) (ttt) | 14,230 | 14,298 | H | 69 | — | 9 | ||

| tRNA-Ala (trnA) (tgc) | 14,308 | 14,374 | H | 67 | — | 22 | ||

| tRNA-Arg (trnR) (tcg) | 14,397 | 14,465 | H | 69 | — | 11 | ||

| tRNA-Asn (trnN) (gtt) | 14,477 | 14,545 | H | 69 | — | 12 | ||

| tRNA-Ile (trnI) (gat) | 14,558 | 14,626 | H | 69 | — | 5 | ||

| nad3 | 14,632 | 14,985 | H | 354 | ATG | TAA | — | 15 |

| tRNA-Ser1 (trnS1) (gct) | 15,001 | 15,068 | H | 68 | — | — | ||

| nad2 | 15,069 | 1 | H | 1,053 | ATG | TAA | — | — |

Table 3.

Nucleotide composition of the mitochondrial genome of Conuslischkeanus.

| Nucleotide sequence | Length (bp) | A (%) | C (%) | G (%) | T (%) | A+T (%) | G+C (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire sequence | 16,120 | 29.0 | 16.3 | 17.6 | 37.1 | 66.1 | 33.9 |

| Protein coding sequence | 11,292 | 26.3 | 17.0 | 17.5 | 39.2 | 65.5 | 34.5 |

| Codon position* | |||||||

| 1st | 3,751 | 26.9 | 17.2 | 24.7 | 31.2 | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| 2nd | 3,751 | 18.3 | 20.9 | 16.6 | 44.2 | 62.5 | 37.5 |

| 3rd | 3,751 | 33.4 | 13.1 | 11.4 | 42.1 | 75.5 | 24.5 |

| Ribosomal RNA gene sequence | 2,327 | 35.5 | 14.4 | 18.4 | 31.6 | 67.2 | 32.8 |

| Transfer RNA gene sequence | 1,481 | 34.0 | 16.2 | 17.7 | 32.1 | 66.1 | 33.9 |

| D-loop region sequence | 586 | 31.1 | 15.4 | 17.6 | 35.8 | 67.1 | 32.9 |

*Termination codons were not included.

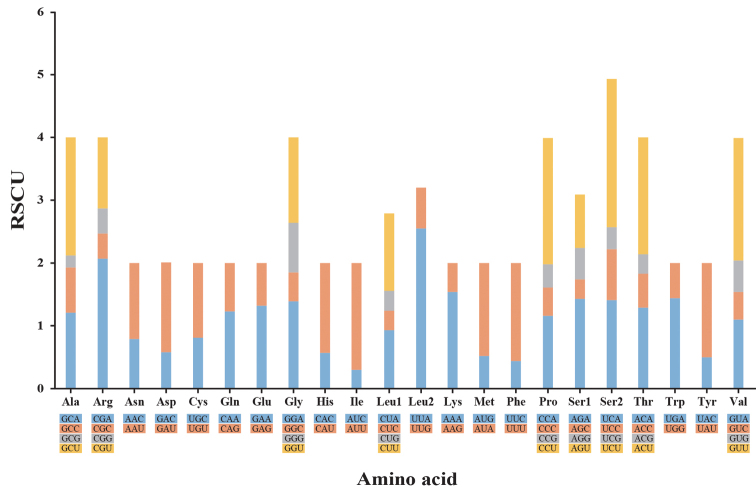

PCGs and codon usage

The lengths of 13 PCGs of C.lischkeanus mitochondria range from 162 bp (atp8) to 1,716 bp (nad5) and contain 3,751 codons, excluding termination codons. The base composition of PCGs is 26.3% A, 39.2% T, 17.5% G, and 17.0% C, and the overall AT content was 65.5%, which is very similar to that of the entire mitochondrial genome sequence (AT content of 66.1%; Table 3). All PCGs have ATG as the initiation codon. With the exception of three PCGs (nad1, nad4L, and nad4) with TAG as a termination codon, all PCGs have TAA as a termination codon, which is consistent with complete mitochondrial genomes previously reported (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2008; Cunha et al. 2009; Brauer et al. 2012; Barghi et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016a, 2016b, 2016c; Gao et al. 2018; Uribe et al. 2018). Fig. 2 shows the RSCU of C.lischkeanus, wherein the five most frequently used codons are UUA (Leu1), UCU (Ser2), CGA (Arg), CCU (Pro), and GUU (Val). In addition, codons with an A or U in the third position are the most frequently used, which is consistent with observations made in other mollusk species (Rawlings et al. 2010; Ren et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2019).

Figure 2.

The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) frequency of the mitochondrial genome of Conuslischkeanus.

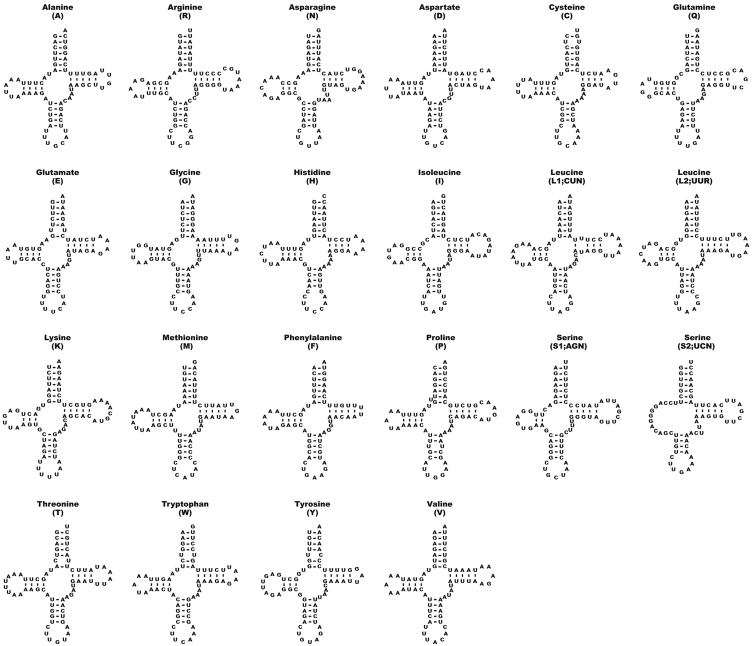

tRNA, rRNA genes, and D-loop regions

Twenty-two tRNA genes were found in the mitochondrial genome of C.lischkeanus. The length of tRNA genes range from 65 bp (trnC, trnE, trnS2, and trnF) to 70 bp (trnL1) (Table 2). All tRNA genes formed typical clover-leaf secondary structures, except for trnS1 and trnS2 which lack or had an imperfect D-arm (Fig. 3), which is common to other mollusk species (Boore 2006; Feng et al. 2020). Meanwhile, two ribosomal RNA genes with a total length of 2,327 bp consisting of small rRNA (rrnS; 952 bp) and large rRNA (rrnL; 1,375 bp) are located between trnE and trnV, and between trnV and trnL1, respectively (Fig. 2, Table 2). The D-loop is 587 bp in length and is located between trnF and cox3, with a short, inverted repeat (IR1; 20 bp), a typical feature of the mitochondrial genome of cone snail species. In contrast, the AT tandem repeat stretch found in C.consors G. B. Sowerby I, 1833 and C.quercinus [Lightfoot], 1786 was not identified in the C.lischkeanus mitochondrial genome (Brauer et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2018).

Figure 3.

Predicted tRNA structures of Conuslischkeanus.

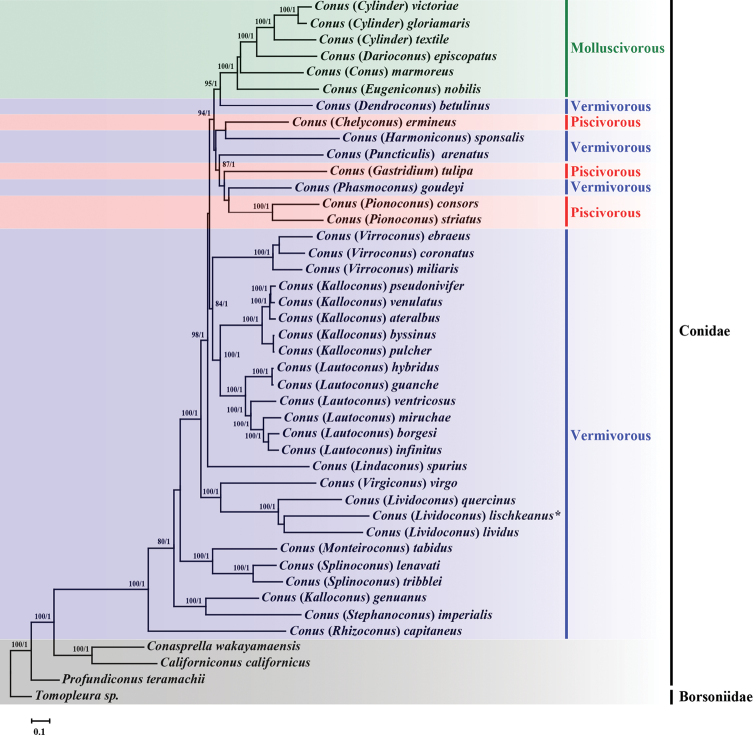

Phylogenetic implication of the evolutionary diversification of dietary specification

Phylogenetic analysis using ML and BI methods yield similar results with respect to the tree topology, as shown in Fig. 4. All subgenera, except Kalloconus da Motta, 1991, were monophyletic. A group of three Conus species, (C.capitaneus+(C.imperialis+C.genuanus)) was positioned at the most basal, but the branch reflected relatively weak supporting values (< 70% bootstrap values). Instead, the next monophyletic group consisting of (C.tabidus+(C.lenavati+C.tribblei)) was strongly supported (100% in ML and 1.0 BPP). Moreover, three species belonging to the subgenus Lividoconus Wils, 1970 (including C.lischkeanus) were grouped together with the subgenus Virgiconus Cotton, 1945 species C.virgo Linnaeus, 1758, a sister to a large assemblage of the remaining Conus species that is composed of two well-supported groupings differing in their feeding type: vermivorous species and a mixture of three diet types. The “vermivorous only” clade is composed of three monophyletic groups of the subgenera Virroconus Iredale, 1930, Kalloconus da Motta, 1991, and Lautoconus Monterosato, 1923, with the latter two more closely related to each other than to Virroconus. Within the “mixed diet” clade, aside from a well-supported molluscivorous species (100% BP in ML and 1.0 BPP in BI), all vermivorous species are grouped either with piscivorous or vermivorous species. It is evident that vermivorous species are not monophyletic and are split into four branches, each forming sister relationships with other molluscivorous and/or piscivorous species. Given the mitochondrial genome phylogeny with vermivorous species positioned at the basal, the tree topology coincides with earlier hypothesis that worm-hunting was the ancestral diet type. Meanwhile, the other two diet types such as molluscivorous and piscivorous were secondarily derived (Duda Jr et al. 2001; Puillandre et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2018; Abalde et al. 2019). Notably, piscivorous species in our phylogenetic tree are not monophyletic and split into three branches, which is not consistent with previous mitochondrial genome phylogeny where fish-hunting species formed a monophyletic group (Gao et al. 2018). The polyphyly of piscivorous species in the current study implies that the fish-hunting species have evolved independently from worm-hunting groups multiple times. The complete mitochondrial genome information of the worm-hunting Conus species (C.lischkeanus) in the present study provides valuable insights into the mitochondrial genome diversity and molecular phylogeny of Conus species.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of the genus Conus based on concatenated nucleotide sequences (13 protein coding genes plus two rRNA genes). Numbers above branches are statistical support values for ML (bootstrap values, > 70)/BI (posterior probability values, > 0.7). *: determined in this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (2022M01100) and the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (no. 2020R1I1A1A01074213; 2020R1A2C2005393).

Citation

Lee Y, Park J-K (2022) Complete mitochondrial genome of Conus lischkeanus Weinkauff, 1875 (Neogastropoda, Conidae) and phylogenetic implications of the evolutionary diversification of dietary types of Conus speciese. ZooKeys 1088: 173–185. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1088.78990

References

- Abalde S, Tenorio MJ, Afonso CML, Zardoya R. (2017) Mitogenomic phylogeny of cone snails endemic to Senegal. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 112: 79–87. 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abalde S, Tenorio MJ, Uribe JE, Zardoya R. (2019) Conidae phylogenomics and evolution. Zoologica Scripta 48: 194–214. 10.1111/zsc.12329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay PK, Stevenson BJ, Ownby J-P, Cady MT, Watkins M, Olivera BM. (2008) The mitochondrial genome of Conustextile, coxI-coxII intergenic sequences and Conoidean evolution. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46: 215–223. 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barghi N, Concepcion GP, Olivera BM, Lluisma AO. (2016) Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Conustribblei Walls, 1977. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27: 4451–4452. 10.3109/19401736.2015.1089566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernt M, Donath A, Jühling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, Pütz J, Middendorf M, Stadler PF. (2013) MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69: 313–319. 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boore JL. (2006) The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Nautilusmacromphalus (Mollusca: Cephalopoda). BMC Genomics 7: e182. 10.1186/1471-2164-7-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brauer A, Kurz A, Stockwell T, Baden-Tillson H, Heidler J, Wittig I, Kauferstein S, Mebs D, Stöcklin R, Remm M. (2012) The mitochondrial genome of the venomous cone snail Conusconsors. PLoS ONE 7: e51528. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen P-W, Hsiao S-T, Chen K-S, Tseng C-T, Wu W-L, Hwang D-F. (2016a) The complete mitochondrial genome of Conuscapitaneus (Neogastropoda: Conidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 1: 520–521. 10.1080/23802359.2016.1197060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P-W, Hsiao S-T, Chen K-S, Tseng C-T, Wu W-L, Hwang D-F. (2016b) The complete mitochondrial genome of Conusstriatus (Neogastropoda: Conidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 1: 493–494. 10.1080/23802359.2016.1192502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P-W, Hsiao S-T, Huang C-W, Chen K-S, Tseng C-T, Wu W-L, Hwang D-F. (2016c) The complete mitochondrial genome of Conustulipa (Neogastropoda: Conidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27: 2738–2739. 10.3109/19401736.2015.1046172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coomans HE, Filmer RM. (1985) Studies of Conidae (Mollusca, Gastropoda) 3. Systematics and distribution of some Australian species, including two new taxa. Beaufortia 35: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RL, Grande C, Zardoya R. (2009) Neogastropod phylogenetic relationships based on entire mitochondrial genomes. BMC Evolutionary Biology 9: 1–16. 10.1186/1471-2148-9-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. (2012) jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature methods 9: 772–772. 10.1038/nmeth.2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda Jr TF, Kohn AJ, Palumbi SR. (2001) Origins of diverse feeding ecologies within Conus, a genus of venomous marine gastropods. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 73: 391–409. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01369.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutertre S, Nicke A, Tyndall JD, Lewis RJ. (2004) Determination of α‐conotoxin binding modes on neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Molecular Recognition 17: 339–347. 10.1002/jmr.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng JT, Guo YH, Yan CR, Ye YY, Li JJ, Guo BY, Lü ZM. (2020) Comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genomes in two limpets from Lottiidae (Gastropoda: Patellogastropoda): rare irregular gene rearrangement within Gastropoda. Scientific Reports 10: e19277. 10.1038/s41598-020-76410-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gao B, Peng C, Chen Q, Zhang J, Shi Q. (2018) Mitochondrial genome sequencing of a vermivorous cone snail Conusquercinus supports the correlative analysis between phylogenetic relationships and dietary types of Conus species. PLoS ONE 13: e0193053. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hahn C, Bachmann L, Chevreux B. (2013) Reconstructing mitochondrial genomes directly from genomic next-generation sequencing reads – a baiting and iterative mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Research 41: e129–e129. 10.1093/nar/gkt371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Himaya S, Jin A-H, Dutertre Sb, Giacomotto J, Mohialdeen H, Vetter I, Alewood PF, Lewis RJ. (2015) Comparative venomics reveals the complex prey capture strategy of the piscivorous cone snail Conuscatus. Journal of Proteome Research 14: 4372–4381. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Lei R, Ding S-W, Zhu S. (2014) Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinformatics 15: 1–12. 10.1186/1471-2105-15-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C. (2012) Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn AJ. (1959) The ecology of Conus in Hawaii. Ecological Monographs 29: 47–90. 10.2307/1948541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn AJ. (2019) Conus envenomation of humans: in fact and fiction. Toxins 11: e10. 10.3390/toxins11010010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. (2018) MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35: 1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kwak H, Shin J, Kim S-C, Kim T, Park J-K. (2019) A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of Mytilidae (Bivalvia: Mytilida). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 139: e 106533. 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106533 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. (2010) Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In: 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE). IEEE, New Orleans, LA, 1–8. 10.1109/GCE.2010.5676129 [DOI]

- Olivera BM, Showers Corneli P, Watkins M, Fedosov A. (2014) Biodiversity of cone snails and other venomous marine gastropods: evolutionary success through neuropharmacology. Annual Review Animal Biosciences 2: 487–513. 10.1146/annurev-animal-022513-114124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna NT, Kocher TD. (1995) Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. Journal of Molecular Evolution 41: 353–358. 10.1007/BF00186547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashanth J, Dutertre S, Jin A, Lavergne V, Hamilton B, Cardoso F, Griffin J, Venter D, Alewood P, Lewis R. (2016) The role of defensive ecological interactions in the evolution of conotoxins. Molecular Ecology 25: 598–615. 10.1111/mec.13504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puillandre N, Bouchet P, Duda Jr T, Kauferstein S, Kohn A, Olivera B, Watkins M, Meyer C. (2014) Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the cone snails (Gastropoda, Conoidea). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 78: 290–303. 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings TA, MacInnis MJ, Bieler R, Boore JL, Collins TM. (2010) Sessile snails, dynamic genomes: gene rearrangements within the mitochondrial genome of a family of caenogastropod molluscs. BMC Genomics 11: 1–24. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Liu X, Jiang F, Guo X, Liu B. (2010) Unusual conservation of mitochondrial gene order in Crassostreaoysters: evidence for recent speciation in Asia. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 1–14. 10.1186/1471-2148-10-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SD, Safavi-Hemami H, McIntosh LD, Purcell AW, Norton RS, Papenfuss AT. (2014) Diversity of conotoxin gene superfamilies in the venomous snail, Conusvictoriae. PLoS ONE 9: e87648. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Röckel D, Korn W, Kohn AJ. (1995) Mannual of the Living Conidae. Vol. 1: Indo-Pacific Region. Verlag Christa Hemmen, Weisbaden, 517 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2014) RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe JE, Puillandre N, Zardoya R. (2017) Beyond Conus: phylogenetic relationships of Conidae based on complete mitochondrial genomes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 107: 142–151. 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe JE, Zardoya R, Puillandre N. (2018) Phylogenetic relationships of the conoidean snails (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda) based on mitochondrial genomes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 127: 898–906. 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WoRMS Editorial Board (2021) World Register of Marine Species. http://www.marinespecies.org [Accessed on: 2021-11-11]