Abstract

Summary

Additional physiotherapy in the first postoperative week was associated with fewer days to discharge after hip fracture surgery. A 7-day physiotherapy service in the first postoperative week should be considered as a new key performance indicator in evaluating the quality of care for patients admitted with a hip fracture.

Introduction

To examine the association between physiotherapy in the first week after hip fracture surgery and discharge from acute hospital.

Methods

We linked data from the UK Physiotherapy Hip Fracture Sprint Audit to hospital records for 5395 patients with hip fracture in May and June 2017. We estimated the association between the number of days patients received physiotherapy in the first postoperative week; its overall duration (< 2 h, ≥ 2 h; 30-min increment) and type (mobilisation alone, mobilisation and exercise) and the cumulative probability of discharge from acute hospital over 30 days, using proportional odds regression adjusted for confounders and the competing risk of death.

Results

The crude and adjusted odds ratios of discharge were 1.24 (95% CI 1.19–1.30) and 1.26 (95% CI 1.19–1.33) for an additional day of physiotherapy, 1.34 (95% CI 1.18–1.52) and 1.33 (95% CI 1.12–1.57) for ≥ 2 versus < 2 h physiotherapy, and 1.11 (95% CI 1.08–1.15) and 1.10 (95% CI 1.05–1.15) for an additional 30-min of physiotherapy. Physiotherapy type was not associated with discharge.

Conclusion

We report an association between physiotherapy and discharge after hip fracture. An average UK hospital admitting 375 patients annually may save 456 bed-days if current provision increased so all patients with hip fracture received physiotherapy on 6–7 days in the first postoperative week. A 7-day physiotherapy service totalling at least 2 h in the first postoperative week may be considered a key performance indicator of acute care quality after hip fracture.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00198-021-06195-9.

Keywords: Audit, Hip fracture, National Hip Fracture Database, Neck of femur, Recovery, Rehabilitation

Introduction

Globally, the incidence of hip fracture is estimated to increase from 2.7 million in 2010 to between seven and 21 million by 2050 [1]. Patients with hip fracture are usually older, living with frailty and poor mobility [2]. These patients often have limited reserve with which to overcome the stress of their injury, the necessary surgery and complete their recovery. Patients with hip fracture describe access to physiotherapy as one of the key factors for their recovery [3]. In the context of postoperative inpatient rehabilitation (average length of stay 15 days), these patients commonly set a goal of returning home as soon as possible [4].

There is inconsistent evidence on what optimal postoperative inpatient physiotherapy consists of for patients after hip fracture. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance is limited to recommending daily mobilisation and regular physiotherapy review [5]. Concern regarding uncertainty on what ‘usual care’ is in the UK led the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) to commission the 2017 Physiotherapy Hip Fracture Sprint Audit (PHFSA) [6]. The audit demonstrated national variation in the duration, frequency and type of acute physiotherapy practice [6] similar to variation observed internationally [7]. A qualitative interview study of physiotherapists’ perceptions of mechanisms for this variation indicated it may be justified by individual patient needs [8]. However, it remains unclear whether the variation in physiotherapy practice influences outcomes after accounting for such patient factors.

Other factors which impact on time to discharge include the promptness of surgery. In 2017, 29% of patients with hip fracture underwent surgery after the recommended 36-h timeframe in the UK, in part reflecting pressures on theatre capacity [2]. This crude proportion has since increased, suggesting a mismatch between demand for surgical services and capacity in a changing patient population [9, 10]. It is not known whether additional postoperative physiotherapy can mitigate the negative effects of delayed surgery[11].

We aimed to determine whether the frequency, duration and type of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week were associated with discharge from acute hospital after accounting for potential confounders and the competing risk of death. We further sought to determine whether these associations varied with time from first presentation and surgery.

Methods

This study is reported according to the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected Data statement [12]. The study did not require NHS Research Ethics Committee approval as it involved secondary analysis of linked pseudo-anonymised data.

Study cohort

The UK National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) is a clinically led, web-based audit, collecting data for over 90% of patients aged 60 years and older with hip fracture and the care they received during their acute hospital admission in England or Wales (UK) [2]. The NHFD also oversees ‘sprint audits’ to capture, for a fixed period of time, additional detailed information on specific aspects of care delivery [13].

In 2017, the CSP commissioned the PHFSA to capture a detailed understanding of the acute physiotherapy management of patients with hip fracture [6]. We linked the individual patient data “routinely” collected by the NHFD to data from the PHFSA, as well as hospital episode statistics (HES) for England, the patient episode database for Wales (PEDW), and the Office of National Statistics (ONS) for additional data on comorbidities, ethnicity, neighbourhood deprivation and mortality. Further details on population selection, codes, and algorithms to classify variables, and person-level linkage across databases are described in Supplementary File 1.

Overall, data were entered into the NHFD for 9250 patients aged 60 years and older, surgically treated for a non-pathological first hip fracture between May 1, 2017, and June 30, 2017. Of these, 5395 patients had additional data collected by physiotherapists for the PHFSA. Following data linkage, we noted patients included in PHFSA were similar to those in the NHFD in terms of several characteristics including age, sex, deprivation, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [14], Hospital Frailty Risk Score [15], American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) grade [16], weekday of admission and procedure type [6]. Patients differed according to pre-fracture mobility (20% [no PHFSA data] vs. 25% [PHFSA data] indoor only), fracture type (57% [no PHFSA data] vs. 59% [PHFSA data] intracapsular), time to surgery (68% [no PHFSA data] vs. 71% [PHFSA data] within 36 h), anaesthetic type (56% [no PHFSA data] vs. 54% [PHFSA data] general anaesthetic), and time of first mobilisation (77% [no PHFSA data] vs. 81% [PHFSA data] within 36 h). There were differences in degree of missing data for ethnicity and pre-fracture residence among patients with data in both PHFSA and NHFD compared with NHFD alone. Additional detail on patients with and without data in the PHFSA are available in Supplementary File 2, Table S1.

Study exposures

The primary study exposure was frequency defined as having received physiotherapy during the first postoperative week on a total of 0–2, 3, 4, 5, or 6–7 days out of a possible 7 days. Secondary exposures included duration and type of physiotherapy. Total duration of physiotherapy during the first post-operative week was classified both as a positive integer and as a binary variable (< 2 h, ≥ 2 h). Type of physiotherapy was classified as mobilisation alone [PHFSA code for mobilisation/gait/transfer practice] or mobilisation and exercises [PHFSA code for mobilisation/gait/transfer practice and range of motion/strength/balance]) within the first postoperative week.

Study outcome

The outcome was discharge from acute hospital care after hip fracture surgery [NHFD code: own home/sheltered housing, nursing care/residential care]. Discharges within the first 7 postoperative days were treated as left censored observations, i.e. the study exposures were not observed. Patients who were transferred to another hospital/unit and/or those with stays longer than 30 days were treated as right censored observations as average acute length of stay was 16 days in 2017 (mean [standard deviation]: 16.0 [0.6] days) [2, 17]. Deaths in hospital were treated as competing events.

Study confounders

We adjusted for variables with a reported association with our study outcome: age [18], sex [18], ethnicity (White, Black or mixed Black, Asian or mixed Asian) [18], deprivation quintiles [18], ASA grade [16], CCI [14], Hospital Frailty Risk Score (low, intermediate, high risk) [15], pre-fracture residence (own home/sheltered housing, nursing care/residential care) [18], fracture type (intracapsular, intertrochanteric/subtrochanteric) [18], prefracture mobility (mobile outdoors with/without aids, some indoor mobility but never goes outdoors without help, no functional mobility) [18], type of anaesthetic (general, spinal) [19], type of surgery (internal fixation, hemiarthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty) [18], timing of surgery (within 36-h target, beyond target) [18], timing of first mobilisation (day of/after surgery, beyond 2 days of surgery) [18], and day of admission (weekday, weekend) [18].

Statistical analysis

For each variable, we estimated median and interquartile range (continuous variables) or frequency and percentage (categorical variables), overall and by exposure. We used χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U test to compare distributions across groups. We estimated the daily rate of discharge by dividing the number of discharges by the total number of inpatient days, overall and by the frequency, duration and type of physiotherapy.

We estimated the cumulative probability of discharge as a function of postoperative day accounting for the event-specific hazard of inhospital death overall and separately for patients in receipt of each exposure level for the frequency (physiotherapy received on 0–2, 3, 4, 5, or 6–7 days of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week), and the duration (total < 2 h, ≥ 2 h of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week), and its type (mobilisation, mobilisation and exercise). We used proportional odds regression models to estimate the association between the cumulative probability of discharge as a function of postoperative day and (1) a 1-day increase in the frequency of physiotherapy; (2) receipt of ≥ 2 h compared to < 2 h physiotherapy; (3) a 30-min increase in physiotherapy duration; and (4) receipt of mobilisation and exercise compared to mobilisation alone, overall and by the timing of surgery (within 36-h target time, beyond 36-h target time). We adjusted for potential confounders if associations were noted in crude models. To assess our findings’ sensitivity to left censoring, we replicated the analysis for exposures: (1) a 1-day increase in frequency of physiotherapy; (2) a 30-min increase in physiotherapy duration; and (3) receipt of mobilisation and exercise compared to mobilisation alone for all patients. The detailed plan of analysis is available in Supplementary File 3. We summarised the differences by 30-day risk differences [20] and by odds ratios [22]. We used R [22] packages CIFsmry [23], cmprsk [24], prodlim [25] and geepack [26] for the analyses.

Missing data analysis

We evaluated patients with complete data for exposures, potential confounders and outcomes for our main analysis. Differences between patients with and without complete data for exposures and outcome are available in Supplementary File 2, Tables S4-S7. We imputed missing data by chained equations to determine whether similar findings would be reached following complete case and imputed analyses [27, 28]. We generated 25 distinct datasets where missing values were replaced with a random sample of imputed values. As in the main analysis, we used proportional odds regression models to estimate the association between the cumulative probability of discharge as a function of postoperative day and the frequency, duration and type of physiotherapy in each of the 25 datasets [27, 29]. We then derived pooled odds ratios, confidence intervals (CI) and p-values across imputed datasets [30].

Results

Patient characteristics

Primary exposure and outcome data were available for a total of 5177 patients. By 30 days after surgery, 2180 hospital stays (42.1%) ended with discharge, 114 stays (2.2%) ended with death, 683 (13.2%) had left censoring events (discharged in first 7 days to home n = 474, to nursing home/residential care n = 154, died n = 55), 1726 (33.3%) had right-censoring events (lost to follow-up), and 474 stays (9.2%) were longer than 30 days (Supplementary File 2, Figure S1). In the first postoperative week, 1026 patients (20%) received physiotherapy on 6–7 out of a possible 7 days, 2647 (53%) received physiotherapy for ≥ 2 h and 4472 (88%) received both mobilisation and exercise (Table 1, Supplementary File 2, Tables S2-S3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients surgically treated for non-pathological first hip fracture overall and by frequency of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week

| Days of physiotherapy in first postoperative week | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 0–2 days | 3 days | 4 days | 5 days | 6–7 days | ||

| n = 5177 | n = 880 | n = 965 | n = 1288 | n = 1018 | n = 1026 | ||

| Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | ||

| Age at admission (years)* | 84 [78–89] | 85 [78–90] | 84 [78–89] | 84 [77–89] | 84 [78–88] | 84 [78–88] | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index† | 1 [1–2] | 2 [1–3] | 1 [1–2] | 1 [0–2] | 1 [0–2] | 1 [0–2] | |

| Length of stay* | 11 [7–18] | 9 [4–18] | 11 [6–18] | 11 [7–17] | 12 [8–18] | 12 [8–17] | |

| Sex | Male | 1,395 (26.95) | 273 (31.0) | 245 (25.4) | 336 (26.1) | 254 (25.0) | 287 (28.0) |

| Female | 3,782 (73.05) | 607 (69.0) | 720 (74.6) | 952 (73.9) | 764 (75.0) | 739 (72.0) | |

| Ethnicity† | White | 3,588 (69.31) | 615 (69.9) | 676 (70.1) | 892 (69.3) | 721 (70.8) | 684 (66.7) |

| Caribbean or African (Black or Black British) or any mixed black background | 10 (0.19) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Asian or Asian British or any mixed Asian background | 37 (0.71) | 7 (0.8) | 7 (0.7) | 10 (0.8) | 6 (0.6) | 7 (0.7) | |

| Deprivation† | Most deprived | 1,187 (22.93) | 198 (20.5) | 279 (21.7) | 250 (24.6) | 236 (23.0) | 198 (20.5) |

| More deprived | 436 (8.42) | 81 (8.4) | 103 (8.0) | 83 (8.2) | 93 (9.1) | 81 (8.4) | |

| Average deprivation | 1,087 (21.00) | 213 (22.1) | 282 (21.9) | 210 (20.6) | 192 (18.7) | 213 (22.1) | |

| Less deprived | 1,030 (19.90) | 198 (20.5) | 257 (20.0) | 211 (20.7) | 200 (19.5) | 198 (20.5) | |

| Least deprived | 1,026 (19.82) | 194 (20.1) | 263 (20.4) | 194 (19.1) | 212 (20.7) | 194 (20.1) | |

| ASA grade*† | I | 114 (2.20) | 18 (2.0) | 19 (2.0) | 38 (3.0) | 23 (2.3) | 16 (1.6) |

| II | 1,256 (24.26) | 159 (18.1) | 228 (23.6) | 321 (24.9) | 282 (27.7) | 266 (25.9) | |

| III | 2,950 (56.98) | 511 (58.1) | 561 (58.1) | 727 (56.4) | 559 (54.9) | 592 (57.7) | |

| IV | 749 (14.47) | 184 (20.9) | 144 (14.9) | 172 (13.4) | 129 (12.7) | 120 (11.7) | |

| V | 16 (0.31) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Prefracture ambulation*† | Freely mobile without aids | 1,860 (35.93) | 247 (28.1) | 344 (35.6) | 478 (37.1) | 371 (36.4) | 420 (40.9) |

| Mobile outdoors with one aid | 1,154 (22.29) | 159 (18.1) | 216 (22.4) | 273 (21.2) | 233 (22.9) | 273 (26.6) | |

| Mobile outdoors with two aids or frame | 784 (15.14) | 147 (16.7) | 136 (14.1) | 184 (14.3) | 177 (17.4) | 140 (13.6) | |

| Some indoor ambulation but never goes outside without help | 1,294 (25.00) | 296 (33.6) | 251 (26.0) | 336 (26.1) | 228 (22.4) | 183 (17.8) | |

| No functional ambulation | 50 (0.97) | 26 (3.0) | 10 (1.0) | 6 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | |

| Hip fracture type† | Intracapsular | 3,065 (59.20) | 501 (56.9) | 538 (55.8) | 774 (60.1) | 614 (60.3) | 638 (62.2) |

| Intertrochanteric | 1,842 (35.58) | 328 (37.3) | 375 (38.9) | 448 (34.8) | 360 (35.4) | 331 (32.3) | |

| Subtrochanteric | 269 (5.20) | 51 (5.8) | 52 (5.4) | 66 (5.1) | 44 (4.3) | 56 (5.5) | |

| Surgery within the target time† | Within target time | 3,710 (71.66) | 618 (70.2) | 704 (73.0) | 920 (71.4) | 743 (73.0) | 725 (70.7) |

| Not within target time | 1,307 (25.25) | 240 (27.3) | 236 (24.5) | 329 (25.5) | 238 (23.4) | 264 (25.7) | |

| Procedure type*† | Internal fixation | 2,451 (47.34) | 443 (50.3) | 487 (50.5) | 601 (46.7) | 477 (46.9) | 443 (43.2) |

| Hemiarthroplasty | 2,312 (44.66) | 379 (43.1) | 416 (43.1) | 568 (44.1) | 461 (45.3) | 488 (47.6) | |

| Total hip replacement | 402 (7.77) | 54 (6.1) | 61 (6.3) | 115 (8.9) | 79 (7.8) | 93 (9.1) | |

| Missing/other | 12 (0.23) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Weekday of admission*† | Weekday (Monday-Friday) | 3,600 (69.54) | 596 (67.7) | 645 (66.8) | 863 (67.0) | 748 (73.5) | 748 (72.9) |

| Weekend (Saturday-Sunday) | 1,571 (30.35) | 283 (32.2) | 318 (33.0) | 423 (32.8) | 269 (26.4) | 278 (27.1) | |

| First mobilisation day of/day after surgery*† | Within target time | 4,180 (80.74) | 591 (67.2) | 784 (81.2) | 1,061 (82.4) | 822 (80.7) | 922 (89.9) |

| After target time | 981 (18.95) | 288 (32.7) | 177 (18.3) | 222 (17.2) | 191 (18.8) | 103 (10.0) | |

| Prefracture residence*† | Own home/sheltered housing | 4,212 (81.36) | 596 (67.7) | 758 (78.5) | 1,066 (82.8) | 873 (85.8) | 919 (89.6) |

| Nursing care/residential care | 962 (18.58) | 284 (32.3) | 207 (21.5) | 222 (17.2) | 142 (13.9) | 107 (10.4) | |

| Anaesthesia type† | General (GA) | 2,776 (53.62) | 483 (54.9) | 532 (55.1) | 702 (54.5) | 546 (53.6) | 513 (50.0) |

| Spinal (SA) | 2,362 (45.62) | 393 (44.7) | 423 (43.8) | 577 (44.8) | 466 (45.8) | 503 (49.0) | |

| Hospital Frailty Index*† | Low risk | 1,127 (21.77) | 156 (17.7) | 202 (20.9) | 307 (23.8) | 227 (22.3) | 235 (22.9) |

| Intermediate risk | 1,800 (34.77) | 268 (30.5) | 319 (33.1) | 461 (35.8) | 355 (34.9) | 397 (38.7) | |

| High risk | 1,886 (36.43) | 403 (45.8) | 371 (38.4) | 428 (33.2) | 375 (36.8) | 309 (30.1) | |

| Duration of physiotherapy*† | < 2 h | 2,647 (51.13) | 847 (96.2) | 765 (79.3) | 616 (47.8) | 283 (27.8) | 136 (13.3) |

| > = 2 h | 2,303 (44.49) | 17 (1.9) | 158 (16.4) | 607 (47.1) | 686 (67.4) | 835 (81.4) | |

| Type of physiotherapy*† | Mobilisation only | 637 (12.30) | 221 (25.1) | 138 (14.3) | 132 (10.2) | 77 (7.6) | 69 (6.7) |

| Mobilisation & exercise | 4,472 (86.38) | 591 (67.2) | 827 (85.7) | 1,156 (89.8) | 941 (92.4) | 957 (93.3) | |

IQR interquartile range

*p < 0.05

†Does not include the following missing data: Charlson Comorbidity Index n = 364, hospital frailty index n = 364, ethnicity n = 1542, deprivation n = 411, ASA grade n = 92, prefracture ambulation n = 35, hip fracture type n = 1, surgery within target time n = 160, procedure type n = 12, weekday of admission n = 6, mobilisation day of/after surgery n = 16, prefracture residence n = 3, anaesthesia type n = 39, duration of physiotherapy n = 227, type of physiotherapy n = 68

The median age of patients was 84.0 years (inter-quartile range (IQR) 77.0–89.0) with a median CCI score of 1.0 (IQR 1.0–2.0). The majority were women (73%), white (70%), admitted from home (82%), and mobile outdoors prefracture (73%). Over one-third were at high risk of frailty (36%) and one-fifth from the most deprived quintile (23%). Fracture type was most commonly intracapsular (59%) with the remainder being extracapsular (trochanteric or subtrochanteric) fractures. Most patients were admitted on a weekday (69%), underwent surgery with general anaesthesia (53%) within the recommended target time (72%), and mobilised on the day of or day after their surgery (81%) (Table 1, Supplementary File 2, Tables S2-S3).

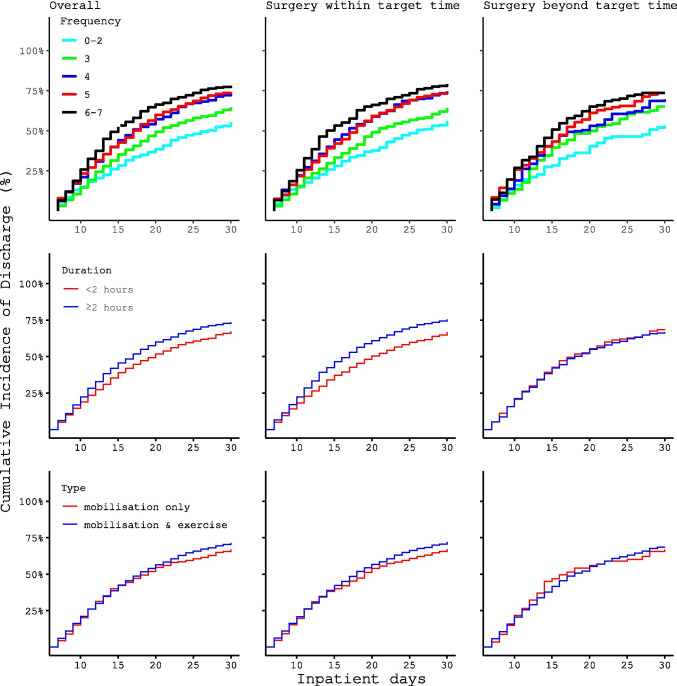

Frequency of physiotherapy

The average rate of discharge was 32 (95% CI 31–33) per 1000 patient days, varying from 22.3 (95% CI 19.7–25.3) among those who received physiotherapy on 0–2 out of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week to 40.4 (95% CI 37.2–43.9) among those who received physiotherapy on 6–7 out of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week (Fig. 1). By day 30, there were an additional 228 (95% CI 166–289) discharges per 1000 patients who received physiotherapy on 6–7 days compared with 0–2 days out of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week. The cumulative incidence of discharge was 704 per 1000 patient days, varying from 533 (95% CI 504–601) among those who received physiotherapy on 0–2 out of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week to 780 (95% CI 745–815) among those who received physiotherapy on 6–7 out of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week (Table 2, Fig. 1). For 1 additional day of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week, the crude and adjusted odds ratios of discharge were 1.24 (95% CI 1.19–1.30) and 1.26 (95% CI 1.19–1.33) respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence of postoperative live discharge by days after surgery among patients surgically treated for non-pathological first hip fracture by frequency, duration, and type of physiotherapy, overall and by surgical timing

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of discharge by frequency, duration and type of physiotherapy among all patients surgically treated for non-pathological first hip fracture, complete case analysis

| Exposure | Number of patients | Number of deaths* | Number of live discharges*† | Live discharge rate (95% CI)†‡ | 30-day CIF, % (95% CI) †‡ | p value †§ | Unadjusted OR of CIF (95% CI) † | Adjusted OR of CIF (95% CI) ǁ† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 5177 | 114 | 2180 |

32.8 (30.6–33.3) |

704 (686–722) |

|||

| Frequency of physiotherapy | ||||||||

| 0–2 days | 880 | 51 | 243 | 22.3 (19.7–25.3) | 553 (504–601) | |||

| 3 days | 965 | 21 | 325 | 25.9 (23.3–28.9) | 646 (601–691) | |||

| 4 days | 1288 | 21 | 569 | 33.3 (30.7–36.2) | 733 (698–768) | |||

| 5 days | 1018 | 13 | 481 | 34.4 (31.5–37.6) | 738 (700–776) | |||

| 6–7 days | 1026 | 8 | 562 | 40.4 (37.2–43.9) | 780 (745–815) | < 0.001 | ||

| 1-day increase | 5177 | 114 | 2180 | 1.24 (1.19–1.30) | 1.26 (1.19–1.33) | |||

| Duration of physiotherapy | ||||||||

| ≥ 2 h | 2647 | 73 | 1005 | 29.2 (27.5–31.1) | 673 (647–699) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| < 2 h | 2303 | 34 | 1069 | 34.7 (32.6–36.8) | 736 (710–762) | < 0.001 | 1.34 (1.18–1.52) | 1.33 (1.12–1.57) |

| 30-min increase | 4950 | 107 | 2074 | 1.11 (1.08–1.15) | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | |||

| Type of physiotherapy | ||||||||

| Mobilisation only | 637 | 18 | 291 | 31.6 (28.2–35.4) | 669 (622–716) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mobilisation & exercises | 4472 | 86 | 1871 | 32.1 (30.7–33.6) | 71.5 (695–734) | 0.2 | 1.11 (0.91–1.36) | 1.21 (0.92–1.60) |

CIF cumulative incidence function, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

*At 30 days from surgery

†Does not include patients with missing discharge and exposure for the analysis of duration (n = 445) and type (n = 286) of physiotherapy

‡Per 1000 patient-days

§Gray’s test for k samples. Pepe-Mori two–sample test

ǁAdjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation, ASA grade, Charlson Comorbidity Index, Hospital Frailty risk score, prefracture residence, fracture type, mobility prior to hip fracture, type of surgery, timing of surgery, anaesthetic type, timing of first mobilisation, day of admission. CIF regression at in-patient days 7, 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, 20, 24, and 30. Includes patients with complete data for exposure, outcome and adjustment variables for the analysis of frequency (n = 3382), duration (n = 3247) and type (n = 3337) of physiotherapy

Duration of physiotherapy

In total, 4950 patients had complete data for physiotherapy duration. The average rate of discharge was 31.8 (95% CI 30.5–33.2) per 1000 patient days, varying from 29.2 (95% CI 27.5–31.1) among those who received < 2 h of physiotherapy to 34.7 (95% CI 32.6–36.8) among those who received ≥ 2 h of physiotherapy, in the first postoperative week (Fig. 1). By 30 days, there were an additional 63 (95% CI 25–101) discharges per 1000 patients who received ≥ 2 h of physiotherapy compared with those who received < 2 h of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week. The crude and adjusted odds ratios of discharge were 1.34 (95% CI 1.18–1.52) and 1.33 (95% CI 1.12–1.57) respectively among those who received ≥ 2 h compared with those who received < 2 h of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week (Table 2). A 30-min increase in physiotherapy in the first postoperative week was associated with crude and adjusted odds ratios of discharge of 1.11 (95% CI 1.08–1.15) and 1.10 (95% CI 1.05–1.15) respectively (Table 2).

Type of physiotherapy

In total, 5109 patients had complete data for physiotherapy type. The average rate of discharge was 32.1 (95% CI 30.7–33.5) per 1000 patient days, being similar among those who received mobilisation alone 31.6 (95% CI 28.2–35.4) and those who received both mobilisation and exercise 32.1 (95% CI 30.7–33.6) (Fig. 1, Table 2). For mobilisation and exercise compared with mobilisation alone in the first postoperative week, the crude odds ratio of discharge was 1.11 (95% CI 0.91–1.36) (Table 2).

Analysis stratified by time to surgery

Similar rates of discharge by physiotherapy frequency, duration and type were observed among the subgroup of patients who underwent surgery within the target time of 36 h from presentation as for the overall analysis (Fig. 1, Supplementary File 2, Table S8). For 1 additional day of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week, the adjusted odds ratio of discharge was 1.29 (95% CI 1.21–1.38) for those who underwent surgery within 36 h and 1.18 (95% CI 1.06–1.31) for those who underwent surgery later (Supplementary File 2 Table S8). Comparing those who received ≥ 2 and < 2 h of physiotherapy, the adjusted odds ratios of discharge were 1.54 (95% CI 1.27–1.86) for those who underwent surgery within 36 h and 0.89 (95% CI 0.63–1.25) for those who underwent surgery later (Supplementary File 2, Table S8). An additional 30 min of physiotherapy in the first postoperative week was associated with adjusted odds ratios of discharge of 1.15 (95% CI 1.09–1.21) for those who underwent surgery within 36 h and 1.02 (95% CI 0.94–1.14) for those who underwent surgery later (Supplementary File 2, Table S8). The crude odds ratio of discharge was similar for those who received mobilisation and exercise and those who received mobilisation alone in the first postoperative week irrespective of time to surgery (Supplementary File 2, Table S8).

Sensitivity and missing data analyses

Supplementary File 2 provides full details of results for analyses without left censoring of patients discharged in the first postoperative week (Table S9) and for analyses with imputation for missing exposure, outcome, and potential confounders (Table S10). Without left censoring, the results were similar to the analysis with left censoring for frequency and type. However, the adjusted odds ratios of discharge were similar among those who received < 2 h and those who received ≥ 2 h physiotherapy in the first postoperative week, and for a 30-min increment in duration of physiotherapy without left censoring (Table S9). The results of imputed analysis were similar to those of the complete case analysis.

Discussion

Key results

These national data show associations between the frequency and the duration of physiotherapy and discharge from acute hospital care after hip fracture surgery. The association for frequency was observed irrespective of surgical timing, whilst the association for duration was only observed for those who underwent surgery within 36 h of hospital presentation. We found no association between the type of physiotherapy delivered and discharge.

Interpretation

The recent United States Physical Therapy Associations Hip Fracture Clinical Practice Guideline recommends offering patients daily physiotherapy during their inpatient stay [31]. However, in the current study, only 20% of patients received physiotherapy on 6–7 out of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week. This is similar to other international studies which noted 13% of patients received physiotherapy on 6–7 of a maximum 7 days a week (Japan) [32], physiotherapy input on a median of 5 days (Australia) [33], or daily until day 3 postoperatively and weekdays thereafter (Denmark) [34].

In the UK, a typical hospital will provide hip fracture surgery to an average of 375 patients annually [2]. For the current study, the difference in the cumulative incidence of discharge between those who received physiotherapy on 6–7 of a possible 7 days in the first postoperative week compared to overall was 76 per 1000 patient days. This equates to a saving of 456 bed days (for an average length of stay of 16 days). Extrapolating this to the 65,958 patients with hip fracture for 2017, this equates to a potential saving of 80,205 bed days or £27,750,905 (based on £346 cost per excess bed day for a non-elective inpatient) [2, 35, 36]. The reported adjusted associations between physiotherapy frequency and discharge were observed irrespective of time to surgery. This suggests that a 7-day physiotherapy service could mitigate the impact of delayed surgery with respect to time to discharge [11]. These findings provide a narrative to support requests for additional staffing to enable implementation of recommended 7-day services [11].[37] Further, the results add weight to the argument for the CSP’s care standard ‘All patients receive daily physiotherapy that should total at least 2 h in the first 7 days post-surgery’ to become a key performance indicator when evaluating the quality of acute postoperative care after hip fracture [6].

Implementing a 7-day service may be a challenge in the absence of additional staffing. Indeed, the PHFSA report indicated ‘staffing issue’ as a key reason why patients did not receive daily physiotherapy in the first postoperative week [6]. Kimmel and colleagues noted a decrease in length of stay following an intensive physiotherapy intervention where participants received more than twice the time in physiotherapy compared to control participants [33]. The current study builds on this previous work highlighting a potential benefit from an additional 30 min of physiotherapy in the first week after surgery. This increase may be achievable within existing resource capacity for some settings. Indeed, group-based rehabilitation may provide an opportunity to increase time in physiotherapy within existing staffing capacity. For example, an Australian inpatient standing balance circuit class of up to eight older adults led by two physiotherapists saw improvements in mobility performance, self-reported functioning and reduction in total length of stay among participants compared to usual care [38].

The reported association between physiotherapy duration and discharge was observed only for those who underwent surgery within the 36-h target time. This may suggest the presence of unmeasured confounding of patient-related factors in the analysis as these factors are likely more evident among those who were delayed to surgery. Indeed, both patient and non-clinical factors may delay surgery for hip fracture [39] which in turn may limit participation in physiotherapy and lead to longer time to discharge. However, a 2011 cohort of 2250 patients in Spain reported acute medical problems (33.1%) and lack of operating room availability (60.7%) as the main drivers of delays beyond 48 h [40]. In the absence of a 7-day physiotherapy service, our findings support reasoning behind efforts to ensure that nonclinical factors do not delay surgery.

Future research

We noted no association between the type of physiotherapy and discharge. This may be due to a lack of detail in our data. Alternatively, it may be a true representation whereby exercise targeting improvements in balance, muscle mass, strength, power and quality do not influence time to discharge. Previous work suggests exercise incorporating balance training of at least 3 h per week over an intervention period of several months is required to reduce falls risk [41], and high intensity progressive resistance training on 2 to 3 days per week for 8 to 12 weeks for improvements in muscle strength, transfers and gait speed among older adults [42]. Finally, it may allude to a benefit of physiotherapy input regardless of type. The findings are in keeping with a recent systematic review which reported exercise in the early postoperative phase after hip fracture surgery led to improvements in physical function but there was uncertainty over the optimal type of exercise [43]. It is therefore unclear whether daily mobilisation (as recommended by NICE guidance[5]) is as effective as a more comprehensive exercise intervention for older adults during their postoperative inpatient stay after hip fracture. This uncertainty should be addressed in future research as there are substantial resource implications with the complexity of an intervention determining the skill set required to support its delivery.

We did not explore the reasons why daily physiotherapy was not provided. For the current dataset, the PHFSA reported ‘contraindications’ as the main reason why physiotherapy was not provided in the first 2 postoperative days and ‘staffing issues’ thereafter [6]. The most frequently reported contraindication was ‘other’ followed by pain and hypotension [6]. The report findings were supported by physiotherapists who specified staffing, pain management, patient/carer and multidisciplinary engagement as barriers to provision of protocolised care in a recent qualitative study [8]. Future research and/or audit should seek to collect data specifying the most frequent contraindications to physiotherapy to enable future intervention to overcome these barriers.

This analysis was focused on the putative association between physiotherapy frequency, duration and type and discharge from acute hospital care after hip fracture surgery. Previous qualitative evidence highlighted discharge home as a defining feature of recovery among patients in the early postoperative phase after hip fracture [4]. However, a recent qualitative synthesis of 14 interview studies (279 participants) indicated older adults considered themselves ‘recovered’ from hip fracture only when they returned to their prefracture activities or a new ‘normal’ which enabled independence to participate in meaningful activities [44]. Future research should consider the association between acute physiotherapy input and longer-term outcomes reflective of activity and participation domains of the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning [45].

Limitations

There are five principal limitations of this study which should be acknowledged. First, there is the potential for unmeasured confounding by variables associated with physiotherapy frequency, duration and/or type and discharge including those related to the patient (e.g. anticoagulation, motivation), admission (e.g. weekend), overall standard of hip fracture care (e.g. hospitals with understaffed therapy services may also be deficient in other aspects of hip fracture care), or postoperative complications (e.g. tachyarrhythmia) which may contribute to the associations observed. It may also be argued that physiotherapy input is related to a patient’s ability to engage in physiotherapy with those more able to engage receiving more input and going home earlier. Alternatively, more physiotherapy input may be required for more dependent patients who require more time and support for safe discharge. Further, our analyses focused on physiotherapy in the first week after surgery and did not account for other interventions such as pain management or additional physiotherapy received between postoperative day eight and discharge (the duration of which varied across patients). We attempted to account for these differences through regression adjustment; however, the risk of unmeasured confounding remains. Second, there is potential for misclassification bias in our exposures. For example, duration of physiotherapy may have been interpreted as ‘time with patient’ as was required by the PHFSA or miscoded using ‘overall treatment time inclusive of note writing’. This may have led to an underestimation or overestimation of the association between duration of physiotherapy and discharge. Third, we excluded patients with missing data from the main analysis. To determine the impact of these exclusions, we completed missing data analyses with multiple imputation for exposure, potential confounders and outcomes. We reported similar but more conservative findings for complete case than imputed analyses. Fourth, for 33% of patients censored following transfer to another hospital/unit, we are unable to confirm whether their discharge prospects are similar to those not censored. Finally, the study findings may not be generalisable to settings where the organisation of care after hip fracture is distinctly different to that provided in England and Wales in the UK. For example, in England and Wales, physiotherapy is not provided preoperatively for patients admitted with hip fracture.

Conclusion

Few patients in the UK receive access to physiotherapy every day in the first 7 days after hip fracture surgery. In this study, we have shown an association between additional physiotherapy and a reduction in time to discharge from acute hospital care. A 7-day physiotherapy service totalling at least 2 h in the first postoperative week may be considered as a key performance indicator against which to measure the quality of acute postoperative care after hip fracture. Benefits may be achieved even by offering an additional 30-min physiotherapy across the first week after surgery. Our findings will help staff in different hospitals to build the case for this additional service.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to NHS Digital, NHS Wales Informatics Service, and the Royal College of Physician’s Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit programme for providing the data used in this study. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care. This publication is based on data collected by or on behalf of Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, who have no responsibility or liability for the accuracy, currency, reliability and/or correctness of this publication.

Funding

The authors have received grants from the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Charitable Trust related to this work (Grant No: PRF/18/A24).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from NHS Digital, NHS Wales Informatics Service, the Royal College of Physician’s Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit programme and Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Code availability

The code is available on request from the study authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study did not require NHS Research Ethics Committee approval as it involves secondary analysis of linked pseudo-anonymised data.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Charitable Trust funding provides salary support for AG, and partial salary support for SA. KS also received funding from the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit and UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship for hip fracture health services research. KS is the Chair and AJ and CG are members of the Scientific and Publications Committee of the Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme which managed the National Hip Fracture Database audit at the Royal College of Physicians. FCM was the funded (2012–2018) board chair and AJ is funded clinical lead of the Falls and Fragility Fracture programme. SA is funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College London, and the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. CS received funding from the National Institutes of Health Research and Dunhill Medical Trust for research not related to the current study. TS received funding from the National Institutes of Health Research for research not related to the current study. CLG receives funding from Versus Arthritis (ref 22086). ES is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Wessex. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. KL, RMC, JM and MTK declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cooper C, Ferrari S on on behalf of the International Osteoporosis Foundation Board and Executive Committee (2019). International Osteoporosis Foundation Compendium of Osteoporosis. http://www.worldosteoporosisday.org/sites/default/WOD-2019/resources/compendium/2019-IOF-Compendium-of-Osteoporosis-WEB.pdf Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 2.Royal College of Physicians (2018) Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme, National Hip Fracture Database Extended Report. https://www.nhfd.co.uk/files/2018ReportFiles/NHFD-2018-Annual-Report-v101.pdf Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 3.Stott-Eveneshen S, Sims-Gould J, McAllister MM, Fleig L, Hanson HM, Cook WL, Ashe MC. Reflections on hip fracture recovery from older adults enrolled in a clinical trial. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2017;3:2333721417697663. doi: 10.1177/2333721417697663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Southwell JP, Wyatt D, Sadler E, Sheehan KJ (2021) Older adults’ perceptions of early rehabilitation and recovery after hip fracture surgery — a UK qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.National Clinical Guideline Centre (2011) The management of hip fracture in adults. London: National Clinical Guidelines Centre www.ncgc.ac.uk Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 6.Royal College of Physicians (2017) Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme. Recovering after a hip fracture: helping people understand physiotherapy in the NHS. Physiotherapy ‘Hip Sprint’ audit report. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/recovering-after-hip-fracture-helping-people-understand-physiotherapy-nhs Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 7.Purcell, K., et al. (2021) Mobilisation and physiotherapy intervention following hip fracture: snapshot survey across six countries from the Fragility Fracture Network Physiotherapy Group. Disabil Rehabil 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Volkmer B, Sadler E, Lambe K, et al. (2021) Physiotherapists’ perceptions of mechanisms for observed variation in the implementation of physiotherapy practices in the early postoperative phase after hip fracture: a UK qualitative study. Age and Ageing. May 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Royal College of Physicians (2019) Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme, National Hip Fracture Database Extended Reporthttps://www.nhfd.co.uk/files/2019ReportFiles/NHFD_2019_Annual_Report_v101.pdf Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 10.Baker PN, Salar O, Ollivere BJ, Forward DP, Weerasuriya N, Moppett IK, Moran CG. Evolution of the hip fracture population: time to consider the future? A retrospective observational analysis. BMJ open. 2014;4(4):e004405. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegmeth AW, Gurusamy K, Parker MJ. Delay to surgery prolongs hospital stay in patients with fractures of the proximal femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(8):1123–1126. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B8.16357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, Sørensen HT, von Elm E, Langan SM, Working Committee RECORD. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royal College of Physicians and Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (2014) Anaesthesia Sprint Audit of Practice. https://www.nhfd.co.uk/20/hipfractureR.nsf/vwContent/asapReport Accessed 16 July 2021.

- 14.Lakomkin N, Kothari P, Dodd AC, VanHouten JP, Yarlagadda M, Collinge CA, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK. Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores are associated with increased hospital length of stay after lower extremity orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, Keeble E, Smith P, Ariti C, Arora S, Street A, Parker S, Roberts HC, Bardsley M. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards T, Glendenning A, Benson D, Alexander S, Thati S. The independent patient factors that affect length of stay following hip fractures. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100(7):556–562. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2018.0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML 2003 Survival analysis. Techniques for censored data and truncated data. Vol. Second Springer.

- 18.Sheehan KJ, Goubar A, Almilaji O, Martin FC, Potter C, Jones GD, Sackley C, Ayis S. Discharge after hip fracture surgery by mobilisation timing: secondary analysis of the UK National Hip Fracture Database. Age Ageing. 2021;50(2):415–422. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuman MD, Rosenbaum PR, Silber JH. Anesthesia technique and outcomes after hip fracture surgery–reply. JAMA. 2014;312(17):1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang MJ, Fine J. Summarizing differences in cumulative incidence functions. Stat Med. 2008;27(24):4939–4949. doi: 10.1002/sim.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MedCalc. Relative risk, risk differences and odds ratio. https://www.medcalc.org/manual/relativerisk_oddsratio.php Accessed 16 July 2021

- 22.R Core Team 2019 R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 3.6.1. Vienna, Austria

- 23.Li J 2016 CIFsmry: Weighted summary of cumulative incidence functions.https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/CIFsmry/ Accessed 16 July 2021

- 24.Gray B. cmprsk: Subdistribution analysis of competing risks, 2014.http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cmprsk Accessed 16 July 2021

- 25.Gerds T. prodlim: Product-limit estimation for censored event history analysis, 2014. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=prodlim Accessed 16 July 2021

- 26.Hojsgaard S, Halekoh U, Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. The Journal of Statistical Software. 2006;15(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Buuren SG-O, K (2011) MICE: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Statistical Software 45.

- 29.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. 2007;8(3):206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin DB Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. 1987, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- 31.McDonough CM, Harris-Hayes M, Kristensen MT, Overgaard JA, Herring TB, Kenny AM, Mangione KK (2021) Physical therapy management of older adults with hip fracture: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy and the Academy of Geriatric Physical Therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 51(2):CPG1–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Uda K, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Intensive in-hospital rehabilitation after hip fracture surgery and activities of daily living in patients with dementia: retrospective analysis of a nationwide inpatient database. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(12):2301–2307. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimmel LA, Liew SM, Sayer JM, Holland AE. HIP4Hips (High Intensity Physiotherapy for Hip fractures in the acute hospital setting): a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2016;205(2):73–78. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hulsbæk S, Ban I, Aasvang TK, Jensen JE, Kehlet H, Foss NB, Bandholm T, Kristensen MT. Preliminary effect and feasibility of physiotherapy with strength training and protein-rich nutritional supplement in combination with anabolic steroids in cross-continuum rehabilitation of patients with hip fracture: protocol for a blinded randomized controlled pilot trial (HIP-SAP1 trial) Trials. 2019;20(1):763. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3845-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lacobucci G. Lack of social care has cost the NHS 2.5 million bed days since last election, charity says. BMJ. 2019;367:l6870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.UK Department of Health and Social Care. Research and analysis NHS reference costs 2015 to 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-2015-to-2016 Accessed 16 July 2021

- 37.Wainwright T, Middleton R 2020 Removing artificial variability from a physiotherapy service helps to reduce length of stay in an orthopaedic enhanced recovery pathway. ScienceOpen Posters Sep 29.

- 38.Treacy D, Schurr K, Lloyd B, Sherrington C. Additional standing balance circuit classes during inpatient rehabilitation improved balance outcomes: an assessor-blinded randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):580–586. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheehan KJ, Guy P, Villa Y, Sobolev B. Patient and system factors of timing of hip fracture surgery: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016939. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidán MT, Sánchez E, Gracia Y, Maranón E, Vaquero J, Serra JA. Causes and effects of surgical delay in patients with hip fracture: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(4):226–233. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N, Paul SS, Tiedemann A, Whitney J, Cumming RG, Herbert RD, Close JC, Lord SR. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(24):1750–1758. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu CJ, Latham NK. Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD002759. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002759.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beckmann M, Bruun-Olsen V, Pripp AH, Bergland A, Smith T, Heiberg KE. Effect of exercise interventions in the early phase to improve physical function after hip fracture — a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2020;108:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beer N, Riffat R, Volkmer B, Wyatt D, Lambe K, Sheehan KJ. Patient perspectives of recovery after hip fracture: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Disability and Rehabilitation: In press; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health, Organisation (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health Accessed 16 July 2021

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from NHS Digital, NHS Wales Informatics Service, the Royal College of Physician’s Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit programme and Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

The code is available on request from the study authors.