Abstract

Rodents play a significant role in the balance of a terrestrial ecosystem; they are considered prey for many predators like owls and snakes. However, they present a high risk to agriculture (damaging crops) and health. These rodents are the main reservoirs of some vector-borne diseases like leishmaniasis. Meriones shawi (MS) and Psammomys obesus (PO) are the primary Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) reservoirs in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). A review on the MS and PO at the MENA scale was explored. A database of about 1500 papers was used. 38 sites were investigated as foci for MS and 36 sites for PO, and 83 sites of Phlebotomus papatasi (Pp) in the studied region. An updated map at the regional scale and the trend of the reservoir distribution was carried out using a performing proper density analysis. In this paper, climatic conditions and habitat characteristics of these two reservoirs were reviewed. The association of rodent density with some climatic variables is another aspect explored in a case study from Tunisia in the period 2009–2015 using Pearson correlation. Lastly, the protection and control measures of the reservoir were analyzed. The high concentration of the MS, PO, and Pp can be used as an indicator to identify the high-risk area of leishmaniasis infection.

Keywords: Hosts, Geographic distribution, ZCL, Seasonality of reservoirs, Climate impacts

1. Introduction

Rodents are mammals with adaptations to terrestrial and arboreal habitats. According to several studies, rodents cause the transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis diseases. Gerbil is desert rats, including a hundred species adapted to arid conditions (Masoumeh et al., 2014).

Globally, several studies recorded that Rhombomys opimus, Tatera indica, Meriones hurrianae, and Meriones libycus gerbils are the principal hosts of the Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) (Javadian et al., 1998; Rasi et al., 2001; Afshar et al., 2011). Gholamrezaei et al., 2016 reviewed and modelled the distribution of ZCL reservoirs in Iran.

The Meriones shawi have been recorded in North Africa since the Middle Pleistocene (Stoetzel et al., 2017). M. libycus is hosts ZCL in Riyadh province and Saudi Arabia (Ibrahim et al., 1994), inhabiting the dry and hot deserts (Johnson et al., 2016). Yaghoobi-Ershadi et al. (1996) recorded that M. libycus was infected by Leishmania major in Badrood city (Central Iran) and the R. opimus was the primary host further east. However, Psammomys obesus is the primary reservoir host of ZCL in Al-Hassa oasis (Elbihari et al., 1987) and primary reservoir host in western Asia including Nizzana and North Africa (Ashford, 2000).

Many papers were studied the physiology of the reservoir (M. libycus deserts of Saudi Arabia) (Johnson et al., 2016), the genetic and reproduction (Boufermes et al., 2014), Systematics, genetic, and evolution of the M. shawi (Stoetzel et al., 2017), reproduction of M. shawi in southern Morocco (Zaime et al., 1992), the taxonomy, genetic, and biochemical of P. obesus (Mostafa et al., 2006) in Tunisia, the systematic and genetic of R. opimus, the reservoir of Leishmania major in central and south Asia (Oshaghi et al., 2011).

M. shawi is among rodents adapted to arid climates (Petter, 1961). In the Middle East and North African countries, the P. papatasi is the principal vector and PO is the host in North Africa (Masoumeh et al., 2014). Like other species such as insect vectors, the leishmaniasis hosts are broadly extending to new sites and the surveillance becomes an urgent action.

In this paper, a review of M. shawi (MS) and P. obesus (PO) at global scale was explored. The M. shawi was found in Tunisia (Ghawar et al., 2011; Ghawar et al., 2014), in Algeria (Aoun and Bouratbine, 2014), in Morocco (Thévenot and Aulagnier, 2006; Ouzaouit, 2000; Ouanaimi et al., 2015; Aoun and Bouratbine, 2014, Postigo, 2010), and in Libya (Kimutai et al., 2009). Regarding P. obesus, it was recorded in Algeria (Aoun and Bouratbine, 2014; Tomás-Pérez et al., 2014), in Tunisia (Tomás-Pérez et al., 2014; Ghawar et al., 2011), in Libya (Aoun and Bouratbine, 2014; Postigo, 2010), in Saudi Arabia (Saliba et al., 1994; Postigo, 2010), Jordan (Postigo, 2010), and in Syria (Postigo, 2010).

Rodents like P. obesus have a diurnal activity, but depending on surrounding temperature; in winter they appear in the middle of the day and summer in the morning and afternoon, and at night avoiding the heat (Biagi, 2004).

The P. papaptasi is the main vector of the ZCL (Parvizi et al., 2005). In the region of PO and MS (MENA countries), the presence of P. papatasi was recorded in Morocco by Lahouiti et al., 2013, Zouirech et al. (2013), Boussaa et al., 2016, Boussaa et al., 2014, Boussaa et al., 2010, Boussaa et al., 2005, Echchakery et al. (2017), Karmaoui (2020), Talbi et al. (2015), in Algeria by Benmahdi-Tabet et al. (2017) and Boudrissa (2005), in Tunisia by Chelbi et al. (2007). However, in Libya it was found by Dokhan (2008), Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012), Ashford et al. (1977), Annajar (1999), Tabit et al. (2005), El-Buni and Refai (2005), in Egypt by Samy et al. (2014) and Ali et al. (2016). The presence of Pp was also signaled in Saudi Arabia by Doha and Samy (2010) in Jordan by Schlein and Jacobson (1999), and in Palestine by Sawalha et al. (2017).

For effective regional surveillance, there is a need to determine the geographical information on these hosts in association with P. papatasi. Consequently, a review of some rodent species linked to cutaneous leishmaniasis was carried out at a regional scale. A special attention was granted to M. shawi (MS) and P. obesus (PO).

This paper explores the rodents and vector of the ZCL data collected throughout the review of a large number of papers in countries with the presence of MS and PO from 1931 to 2017. The study was designed to explore the associations between the two reservoirs and the P. papatasi main vector of L. major. The findings can affirm, update or change our understanding of the repartition of the ZCL disease. Furthermore, this distribution can help to determine the expansion of the disease with time and the area where surveillance and control of both rodents and vectors must be taken.

2. Material and methods

To update the geographic distribution of rodent hosts of cutaneous leishmaniasis, various, scientific databases (Science Direct, Plos, Wiley, and Google Scholar) were used for papers from 1931 to 2017. The headings terms used in this review were “Leishmaniasis”, “Rodent”, “Hosts”, “Reservoirs”, “Epidemiology”, and the scientific name of some rodent species was also used, mainly, M. shawi (MS) and P. obesus (PO).

Geographic and ecological data on MS, PO, and P. papatasi were extracted and used from a large number of papers (1500). The studied species were confirmed in several countries. In this endemic region, many forms of leishmaniasis were found and several recent epidemic outbreaks have been hosted (McDowell et al., 2011).

The input of geographic and ecological data was processed using the GIS software (Arc-Gis v.10). Mapping the species distribution density of M. shawi (MS), P. obesus (PO) and Phlebotomus papatasi (PP) was carried out using the point density tool. This method allows estimating the density of point features around each output raster cell (http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.3/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/how-point-density-works.htm). The analysis was done using the following steps as explained in the Quantifying Point Patterns (https://mgimond.github.io/ArcGIS_tutorials/Point_pattern_analysis.htm#_Toc519667228):

-

•

Using a vector layer, the process allow to create of a raster;

-

•

Define the extent in the Environments setting;

-

•

Populate the Point Density tool fields (input point feature, population field, output raster, output cell size, and neighborhood settings;

-

•

Run the geoprocessing.

The used cell size (x, y) is (0.086941467, 0.086941467), with the angular unit: Degree (0.0174532925199433).

The mapping of the risk caused by the presence of one or more species (reservoirs or vector) is ensured by the toolbox (Raster calculator) of Arc-GIS software, which allowed aggregate isolated risks and produced a global map whose degree risk varies between 1 (Very low risk) and 4 (High risk) (Table 1).

Table 1.

ZCL degree risk according to the reservoirs and vector densities and associations.

| Type of association | Risk degree |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Meriones shawi | + | |||

| Psammomys obesus | + | |||

| Phlebotomus papatasi | + | |||

| P. obesus + M. shawi | + | |||

| P. obesus + M. shawi | + | |||

| Phlebotomus papatasi + P. obesus | + | |||

| P. obesus + M. shawi + Phlebotomus papatasi | + | |||

The spatial dispersal of P. obesus, M. shawi, and Phlebotomus papatasi was used to draw the maps of distribution, density, and leishmaniasis risk.

Lastly, the association between the rodents and some climatic variables was another aspect studied in this review. A case study from Tunisia was carried out. The climatic variables (rainfall, maximum, minimum and average temperature, and relative humidity) and rodent density data were referred to the supplements presented in the work of Talmoudi et al. (2017). To our knowledge is the only study in the MENA region that provides numeric data for seasonal rodents associated with maximum and minimum, rainfall, relative humidity, and seasonal cases of ZCL.

A statistical analysis of the data through a Pearson correlation is a descriptive method associating the climatic and biological variables with the ZCL incidence. The method makes it possible to explore the various relationships, the fluctuations, and trends of the ZCL disease and the variables mentioned above in the central region of Tunisia for seven years (2009–2015). This correlation between climatic variables (temperature, rainfall, and humidity) and leishmaniasis cases were also investigated by many researchers, particularly by Chalghaf et al. (2016) and Toumi et al. (2012) using interesting modeling approaches.

3. Results and discussion

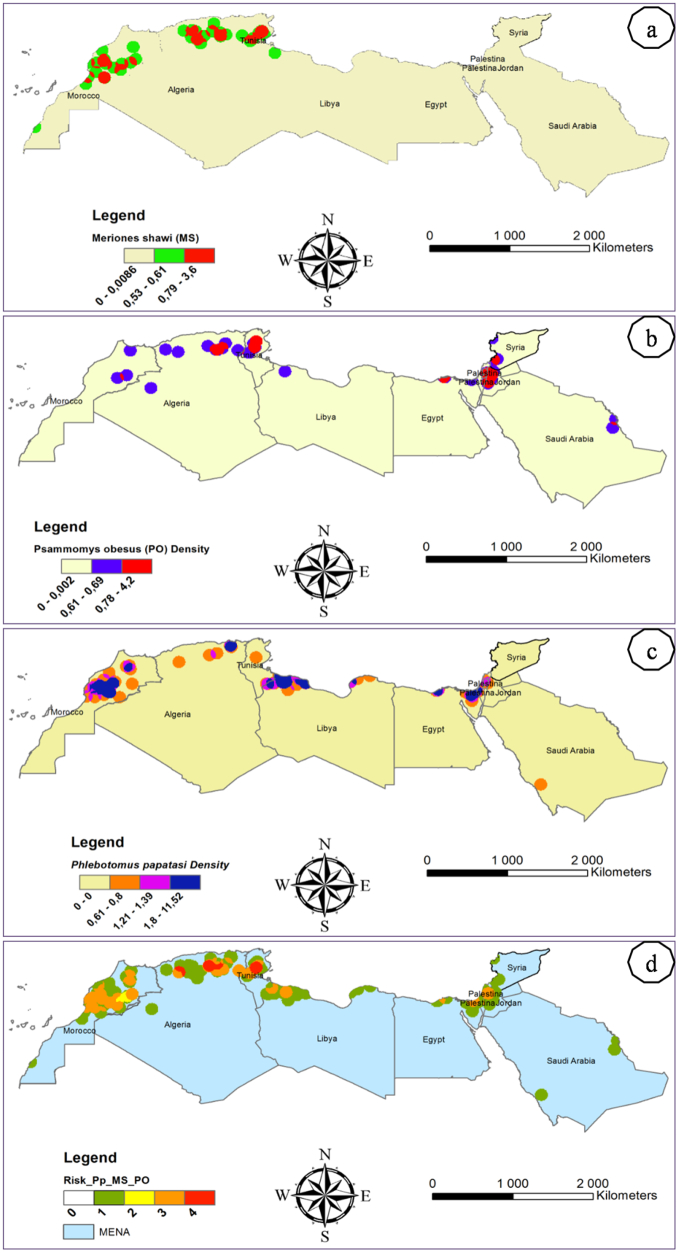

The geographic information was gathered and compiled in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

:Geographic information on Meriones shawi in 8 countries (38 sites).

| Country | Zone | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude | Period | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morocco | Ouarzazate | 30°55′N | 6°55′W | 1100 | 2005 | Boussaa et al. (2010) |

| Boulmane | 33°21′N | 4°43′W | 1730 | – | Settaf et al. (2000) | |

| Al-Haouz | 31°22′N | 7°48′W | 318–2579 | 2014–2015 | Echchakery et al. (2017) | |

| Zagora Tamezmoute |

30°39′N | 6°08′W | 855 | 2015 | El Mezouari et al. (2015) | |

| Marrakech | 31°42”N | 8°04′W | 318–2579 | 2014–2015 | Echchakery et al. (2017) | |

| Oulad Fredj | 32°57′N | 8°13′W | 125 | – | Delanoe (1931) | |

| Tata center | 29°44′N | 7°57′W | 681 | – | Rioux et al. (1982) | |

| Tata oasis | 29°45′N | 7°59′W | 705 | Petter (1988) | ||

| Errachidia | 31°56′N | 4°26′W | – | 2010–2012 | Bennis et al. (2015) | |

| Essaouira | 31°30′N | 09°46′W | – | 2006–2011 | Diatta et al. (2012) | |

| Palm grove Tinejdad | 31°30′N | 5°01′W | 1000 | 2006 | Earl (2006) | |

| Tagdilt -Boumalne Dadès | 31°22′N | 5°59′W | 1522 | 2017 | Kehoe (2017) | |

| Marrakech | 31°50′N | 07°58′W | – | 2006–2011 | Diatta et al. (2012) | |

| Chichaoua | 31°32′N | 8°45′W | 395 | 2014–2015 | Echchakery et al. (2017) | |

| Taroudant | 30°24′N | 08°55′W | – | 2006–2011 | Diatta et al. (2012) | |

| N of Aglou | 29°50′N | 9°48′W | – | 2006–2011 | Diatta et al. (2012) | |

| Guelmim | 29°00′N | 10°03′W | 310 | – | Blanc et al. (1947) | |

| Dakhla | 23°54′N | 15°48′W | – | 2006–2011 | Diatta et al. (2012) | |

| Algeria | Aïn Skhouna 1 | 34°80′N | 1°55′E | 1000 | 2010 | Benmahdi-Tabet et al. (2017) |

| Aïn Skhouna 2 | 34°15′N | 2°30′E | 1000 | 2010 | ||

| Aïn Skhouna 3 | 34°29′N | 1°50′E | 1000 | 2010 | ||

| El M'hir | 36°7′N | 4°22′E | 502 | 2009 | Boudrissa et al. (2012) | |

| Ksar Chellala | 35°13′N | 2°19′E | 750–900 | 1986 | Belazzoug (1986) | |

| Aïn Témouchent | 35°17′N | 0°59′E | 254 | 2009–2012 | Malek et al. (2015) | |

| Laghouat | 33°47′N | 2°52′E | 790 | 2009–2012 | Malek et al. (2015) | |

| Djelfa | 34°39′N | 3°15′E | 1150 | 2009–2012 | Malek et al. (2015) | |

| M'Sila | 35°13′N | 34°11′E | 550 | 2009–2012 | Malek et al. (2015) | |

| Biskra | 34°49′N | 5°44′E | 100 | 2009–2012 | Malek et al. (2015) | |

| Biskra, Branis | 35°03′N | 5°6′E | – | 2008–09 | Bachar (2015) | |

| Biskra,Tolga | 34°42′N | 6°93′E | – | 2008–09 | Bachar, 2015) | |

| Biskra, Doucen | 34°45′N | 4°57′-5°17′E | 120 | 2008–09 | Bachar (2015) | |

| Biskra, Sidi okba | 34°45′N | 5°5′E | 120 | 2008–09 | Bachar (2015) | |

| Tunisia | Sidi Bouzid EL KHBINA |

35°10′N | 9°43′E | 221 | 2008–2010 | Ghawar et al. (2011) |

| Sidi Bouzid EL MNARA |

35°16′N | 9°45′E | 215 | 2008–2010 | Ghawar et al. (2011) | |

| Sidi Bouzid ETTOUILA | 34°58′N | 9°26′E | 434 | 2008–2010 | Ghawar et al. (2011) | |

| Gafsa Douara |

34°23′N | 8°47′E | 400 | 1987 | Ben Ismail et al. (1987) | |

| Sidi Bouzid AL MNARA |

35°12′N | 9°49′E | 80 | 2012 | Ghawar et al. (2015) | |

| Bouhedma | 34°47′N | 9°64′E | – | 2007–2014 | Khemiri et al. (2017) | |

| Dghoumes | 34°03′N | 8°27′E | – | 2007–2014 | Khemiri et al. (2017) | |

| Sidi Toui | 32°39′N | 11°14′E | – | 2007–2014 | Khemiri et al. (2017) |

Table 3.

Geographic information on Psammomys obesus in 8 countries (36 sites).

| Country | Zone | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude | Period | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morocco | Boumalne Dadès (Tagdilt) | ~31°22′N | ~5°59′W | – | 2006 | Earl (2006) |

| Near Goulmima | ~31°41′N | ~4°57′W | – | 2017 | Kehoe (2017) | |

| Algeria | El M'hir | 36°7′N | 4°22′E | 502 | 2009 | Boudrissa et al. (2012) |

| M'sila | 34°40′N | 4°32′E | 1983 | Belazzoug (1983) | ||

| Ouarourout (Beni-Abbes) | 30°9′N | 2°13′W | 450 | 1974 | Daly and Daly (1974) | |

| M'Sila | 35°13′N | 34°11′E | 550 | 2009–2012 | Malek et al. (2015) | |

| Batna | 35°32′N | 6°09′E | 1050 | 2009–2012 | Malek et al. (2015) | |

| Biskra, Branis | 34°57′N | 5°47′E | – | 2008–09 | Bachar (2015) | |

| Biskra,Tolga | 34°42′N | 6°93′E | – | 2008–09 | Bachar (2015) | |

| Biskra, Doucen | 34°45′N | 4°57′-5°17′E | 120 | 2008–09 | Bachar (2015) | |

| Biskra, Sidi okba | 34°45′N | 5°5′E | 120 | 2008–09 | Bachar (2015) | |

| Saoura Valley Ben-Abbes |

34°47′N | 0°34′W | 880 | 1997 | Khammar and Gernigon-Spychalowicz (1997) | |

| Aïn Skhouna | 34°30′N | 0°50′E | 1000 | 2010 | Benmahdi-Tabet et al. (2017) | |

| Tunisia | Sidi Bouzid | 35°02′N | 9°28′E | 330 | 1995–96 | Fichet-Calvet et al. (2000) |

| Sidi Bouzid R' mila |

35°46′N | 9°36′E | 280 | 1995–1997 | Fichet-Calvet et al. (2003) | |

| Sidi Bouzid EL KHBINA |

35°06′N | 9°26′E | 198 | 2008–2010 | Ghawar et al. (2011) | |

| Sidi Bouzid EL MNARA |

35°08N | 9°26′E | 205 | 2008–2010 | Ghawar et al. (2011) | |

| Sidi Bouzid OULED MHAMED |

35°30′N | 9°18′E | 310 | 2008–2010 | Ghawar et al. (2011) | |

| Gafsa Douara |

34°23′N | 8°47′E | 400 | 1987 | Ben Ismail et al. (1987) | |

| Garat an Njila Sidi Bouzid |

35°46′N | 9°36′E | 280 | 1995–1996 | Fichet-Calvet et al. (1999) | |

| Syria | Damascus Dmeir |

33°38′N | 36°41′E | 680 | 1990–91 | Rioux et al. (1992) |

| Damascus | ~33°20′N | ~36°10′E | – | – | WHO, 2010 | |

| Libya | Wadi Al-Hai | 32°9′N | 12°50′E | 300 | 1999 | Annajar (1999) |

| Egypt | Mastroh | 31°28′N | 30°41′E | 10 | – | Basuony (2000) |

| El-Kom El- Akhdar |

31°26′N | 30°49′E | 10 | – | Basuony (2000) | |

| Al Arish, North Sinai | 31°07′N | 33°48′E | 22 | – | Morsy et al. (1996) | |

| Jordan | Qatraneh | 31°15′N | 36°03′E | 770 | – | Saliba et al. (1994) |

| Hasa | 30°53′N | 35°40′E | 1133 | – | Saliba et al. (1994) | |

| Umm ar-Rasas | 31°29′N | 35°54′E | 750 | – | Saliba et al. (1994) | |

| Mowaqqar | 31°48′3N | 36°06′E | 915 | – | Saliba et al. (1994v | |

| Khaldyah | 32°09′N | 36°17′E | 590 | – | Saliba et al. (1994) | |

| Karameh | 31°56′N | 35°34′E | −200 | – | Saliba et al. (1994) | |

| Gharandal | 30°42′N | 35°39′E | 1387 | – | Saliba et al. (1994) | |

| North of Jericho | 32°00′N | 35°30′E | – | 1996–97 | Schlein and Jacobson (1999) | |

| Saudi Arabia | Eastern province (Dammam) |

~26°25′N | ~49°59′N | – | – | WHO (2010) |

| Al-Hassa (sud-est) |

~25°22′N | ~49°39′N | – | – | Petter (1988) |

Table 4.

Geographic distribution of P. papatasi (83 sites).

| Country | Zone | Latitude | Longitude | Period | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morocco | Moulay Yacoub Oulad aid | ~34°05′N | ~4°45′W | 2011–2012 | Lahouiti et al. (2013) |

| Moulay Yacoub Zlilig | 33°57°N | 5°05W | 2011–2012 | Lahouiti et al. (2013) | |

| Azilal province, Ouaouizaght district |

32°09′27”N | 6°20′57, 58W | 2010 | Zouirech et al. (2013) | |

| Azilal | 31°58′N | 6°34′W | – | Boussaa et al. (2014) | |

| Ait Majden | 31°84′N | 6°96′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Damnate | 31°73′N | 7°00′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Zemrane | 31°53′N | 8°26′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Marrakech city | 31°36′N | 8°02′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Ouarzazate | 30°55′N | 6°55′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Fedragon | 30°55′N | 6°58′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Tabourihit | 30°58′N | 7°07′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Amezgan | 31°02′N | 7°12′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| IminTiflet | 31°06′N | 7°16′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Tagouimat | 30°37′N | 7°34′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Aguim | 31°09′N | 7°28′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Douar | 30°21′N | 7°96′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Touama | 31°31′N | 7°28′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Tafriat | 31°32′N | 7°36′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Marrakech city | 31°36′N | 8°02′W | 2005–2006 | Boussaa et al. (2010) | |

| Al-Haouz | 31°22′N | 7°48′W | 2014–2015 | Echchakery et al. (2017) | |

| Al Haouz | 31°22′N | 7°51′W | – | Boussaa et al. (2014) | |

| Marrakech | 31°42′N | 8°04′W | 2014–2015 | Echchakery et al. (2017) | |

| Marrakech Urban | 31°36N | 8°02W | – | Boussaa et al. (2005) | |

| Sefrou | 33°39N | 04°38W | – | Talbi et al. (2015) | |

| Azilal | 31°58′N | 6°34′W | – | Boussaa et al. (2014) | |

| Chichaoua | 31°20′N | 8°30′W | – | Echchakery et al. (2017) | |

| Chichaoua | 31°32′N | 8°45′W | – | Boussaa et al. (2014) | |

| Agadir | 30°25′N | 9°34′W | 2013 | Boussaa et al. (2016) | |

| Essaouira | 31°30′N | 9°45′W | 2013 | Boussaa et al. (2016) | |

| Marrakech | 31°39′N | 7°59′W | 2013 | Boussaa et al. (2016) | |

| Ouarzazate | 30°55′N | 6°56′W | 2013 | Boussaa et al. (2016) | |

| Zagora | 30°20′N | 5°50′W | 2013 | Boussaa et al. (2016) | |

| Errachidia | 31°55′N | 4°25′W | 2013 | Boussaa et al. (2016) | |

| Algeria | Aïn Skhouna | 34°30′N | 0°50′E | – | Benmahdi-Tabet et al. (2017) |

| El Hodna | 35°18′–35°32′N | 4°15′-5°06′E | 2004 | Boudrissa (2005) | |

| El khroub Wilaya Constantine (WC) |

36°16′N | 6°42′E | 2013–2014 | Sahraoui and Nasri (2015) | |

| Hamma Bouziane (WC) | 36°25′N, | 6°36′E | 2013–2014 | Sahraoui and Nasri, 2015 | |

| Didouche Mourad (WC) | 36°27′N | 6°38′E | 2013–2014 | Sahraoui and Nasri (2015) | |

| Tunisia | Sidi Bouzid | ~35°02′N | ~9°28′E | 2005 | Chelbi et al. (2007) |

| Libya | Ajaylat Sabratah Surman | 32°45′N | 12°22′E | – | Dokhan (2008) |

| Fateh Misratah | 32°01′N | 15°02′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Al Marg | 32°30′N | 20°53′E | – | Ashford et al. (1977) | |

| Sawadek Misratah | 32°01′N | 15°07′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Al Twailah An Nuqat Al Khams |

32°49′N | 12°11′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Bani Walid Tarhuna | 31°59′N | 13°58′E | – | Dokhan (2008) | |

| Benghazi Al Hizam Al Akhdar | 32°10′N | 20°06′E | – | Ashford et al. (1977) | |

| Berka Al Hizam Al Akhdar | 32°06′N | 20°04′E | – | Ashford et al. (1977) | |

| East Millitah An Nuqat Al Khams | 32°51′N | 12°12′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| El Bedarna Nalut | 31°58′N | 11°31′E | 1992–94 | Annajar (1999) | |

| Ghazayia Nalut | 31°54′N | 10°48′E | 1992–94 | Annajar (1999) | |

| Guassem Mizdah | 31°11′N | 13°03′E | – | Dokhan (2008) | |

| Janzour Tripoli | 32°49′N | 13°00′E | – | Tabit et al. (2005) | |

| Kikla Al Jifarah | 32°05′N | 12°42′E | 1975 | Ashford et al. (1976) | |

| North west El Gedida Sabratah Surman |

32°48′N | 12°15′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Rabta Yefern-Jadu | 32°23′N | 12°33′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Rabta El Gharbiyah Al Jifarah |

32°09′N | 12°50′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Sabratah Surman | 32°47′N | 12°29′E | – | Dokhan (2008) | |

| Taurgha Medical Center Misratah | 32°00′N | 15°04′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Tiji Nalut | 32°00′N | 11°21′E | 1992–94 | Annajar (1999) | |

| Tripoli Tripoli | 32°53′N | 13°10′E | – | Ashford et al. (1977) | |

| Uazzen Nalut | 31°56′N | 10°39′E | 1975 | Ashford et al. (1976) | |

| Umm El Gersan Gharyan | 32°02′N | 12°33′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Wadi Al Hayy Al Jifarah | 32°18′N | 12°44′E | 1975 | Ashford et al. (1976) | |

| Wadi Bir Ayyad Yefern-Jadu | 32°09′N | 12°25′E | 1975 | Ashford et al. (1976) | |

| Wadi Kiaam Al Marqab | 32°27′N | 14°25′E | – | Dokhan (2008) | |

| Wadi Latrun Al Qubbah | 32°51”N | 22°16′E | – | Ashford et al. (1977) | |

| West El Gedida Sabratah Surman |

32°46′N | 12°14′E | 2010 | Abdel-Dayem et al. (2012) | |

| Zawia Al Zawiyah | 32°44′N | 12°43′E | – | Dokhan (2008) | |

| Yafran Gharyan | 32°03′N | 12°31′E | 1975 | Ashford et al. (1976) | |

| Ziliten Al Marqab | 32°27′N | 14°33′E | – | Dokhan (2008) | |

| Zwara An Nuqat Al Khams | 32°56′N | 12°04′E | – | El-Buni and Refai (2005) | |

| Al Rabta East village | 32°9′N | 12°50′E | 2012–2013 | Dokhan et al. (2016) | |

| Al Rabta West village | 32°9′N | 12°50′E | 2012–2013 | Dokhan et al. (2016) | |

| Egypt | North Sinai | 30°57′N | 34°21′E | 2005–2011 | Samy et al. (2014) |

| North Sinai | 31°01′N | 34.12′E | 2005–2011 | Samy et al. (2014) | |

| Beer Lehfen | 30°36′N | 33°37′E | 2005–2011 | Samy et al. (2014) | |

| Sheikh Zuweid | 30°53′N | 34°04′E | 2005–2011 | Samy et al. (2014) | |

| Rafah | 31°17′N | 34°14′E | 2005–2011 | Samy et al. (2014) | |

| Nekhel | 29°54′N | 33°44′E | 2005–2011 | Samy et al. (2014) | |

| El Hassana | 30°27′N | 33°47′E | 2005–2011 | Samy et al. (2014) | |

| Alexandria (Al-Agamy Province) | 31°05′N | 29°45′E | 2010 | Ali et al. (2016) | |

| Alexandria Al- (Hawareya) | 31°14′N | 29°58′E | 2010 | Ali et al. (2016) | |

| Alexandria (Old King Mariout) | 31°09′N | 29°54′E | 2010 | Ali et al. (2016) | |

| Saudi Arabia | Al-Baha | ~20°00′N | ~41°30′E | 1996–1997 | Doha and Samy (2010) |

| Jordan | North of Jericho | 32°00′N | 35°30′E | – | Schlein and Jacobson (1999) |

| Palestine | Jenin District | 32°20′N | 35°8′E | 2011 | Sawalha et al. (2017) |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of Meriones shawi (MS), Psammomys obesus (PO), and Phlebotomus papatasi (Pp) in the MENA countries.

To find associations between the two reservoirs of L. major, a review of the distribution of the main vector of this disease was done (Table 4). In addition, the database of papers was also used to extract the distribution of P. papatasi in the countries MENA with MS and PO as hosts.

4. Rodents and Phlebotomus papatasi geographic distribution

This study revealed the spatial distribution of the main reservoirs and vector of ZCL in MENA countries using spatial statistical analysis. Similar studies have been used to explore the leishmaniasis vectors in Brazil (Menezes et al., 2015) and the leishmaniasis outbreak in Spain (Gomez-Barroso et al., 2015). The collected and gathered information in this review allow the realization of a spatial distribution of two main reservoirs of ZCL, P. obesus and M. shawi and the associated vector, P. papatasi. Therefore, this review can constitute a database on reservoirs and vector of ZCL in arid regions. A map (Fig. 2) on MENA countries showing these reservoirs and the principal vector performing proper density analysis was carried out. In Fig. 2a, the M. shawi is concentrated mainly in Morocco (center and southeastern part), in Algeria (North), and Tunisia (Center). For the P. obesus, Fig. 2b shows a high density between Palestine and Jordan, north of Algeria and Central Tunisia followed by Morocco, Libya, and Egypt. Aoun and Bouratbine (2014) note the same distributed through the semi-desert. However, the ZCL vector is mainly active in the north of the MENA countries with a high density observed in Morocco, Libya, and Palestine-Jordan (Fig. 2c). Fig. 2d depicts the association between the two reservoirs and the peincipal vector of the ZCL. This map shows a very high risk of leishmaniasis in northern Algeria, Central Tunisia, and a high risk in Morocco (Center and southeastern). The increase of cutaneous leishmaniasis incidence was reported since the 1980s in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya (Anon & Bouratbine, 2013). However, in Egypt, a low risk of leishmaniasis is recorded, which is in accordance with Alvar et al. (2012) reporting a low number of leishmaniasis cases.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of PO, MS, and Phlebotomus papatasi and their associations in the study area.

This paper presents the first study exploring the spatial analysis of the main reservoirs and the vector of L. major in the MENA region. Reviewing the Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (the three types: L. major, L. tropica, and L. major) in North Africa (Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt), Anon & Bouratbine (2013) describe the same geographical distribution of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases. This spatial method showed that the North African countries are highly at risk and can be affected by the ZCL. Moreover, the density of the studied reservoirs and the primary vector were spatially associated and correlated with the distribution of ZCL found by Anon & Bouratbine (2013).

These findings are in accordance with previous studies noting that this disease can be associated with the reservoirs and vector. P. obesus is the main host of ZCL in Al-Hassa oasis (Elbihari et al., 1987) in western Asia including Nizzana and North Africa (Ashford, 2000). M. shawi is the reservoir of L. major in Tunisia (Foroutan et al., 2017; Ghawar et al., 2011), and the vector P. papatasi is associated with ZCL (WHO, 2010).

When associating the two reservoirs on one side and a reservoir with the vector on another side, three maps were traced (Fig. 3). The associations between P. obesus and M. shawi (Fig. 3a) allow observing a high density in southeastern Morocco and the northern parts of Algeria and central Tunisia. In regards to the relationship between P. papatasi and P. obesus, a high density was recorded in the southeastern of Morocco, the northern side of Algeria, Libya (in the west), Central Tunisia, and Palestine. Finally, for the correlation between the density of P. papatasi and M. shawi, Morocco presents a very high risk, followed by Algeria and Tunisia. The maps in Fig. 2, Fig. 3 can demonstrate the geographic region with high risk of ZCL and take the output information in formulating an international control program. Such need was expressed in 2005 in the 5th International Symposium on Phlebotomine Sandflies hosted in Tunisia and also in the research and policy conference, entitled LEISHMANIA hosted in Tunisia (in June 2009).

Fig. 3.

a, Density map of PO and MS; b, Density map of PP and PO; c, Density map of PP and MS and Phlebotomus papatasi and their associations in the studies areas

Considering the fact the current study is subject to the limitations of the different periods of the sites and the restricted number of sites to conduct a large-scale spatial distribution study, active regional collaboration is required. Effective scientific cooperation between the MENA countries on the spatial expansion knowledge of the main reservoirs and vectors (annual and monthly data) of the ZCL can give a global vision and open new ways for investigation on leishmaniasis burden. In this context, McDowell et al. (2011) recorded the necessity of global capacity building in science and the participation of the global scientific community. Such collaboration was previously performed by a team of 36 researchers from 8 Mediterranean countries, Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, and Georgia. The study was entitled Seasonal Dynamics of Phlebotomine Sand Fly Species Proven Vectors of Mediterranean Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania infantum (Alten et al., 2016). This research project is an excellent example for the MENA region whose ZCL is endemic.

5. Rodents and climate, a case study from Tunisia

The impact of climate on the distribution of animal species was studied by Graham in the early 90's (Graham and Grimm, 1990; Graham, 1992; Graham et al., 1996). The climate models allowed predicting the repartition of species based on environmental requirements were used by Hijmans and Graham (2006).

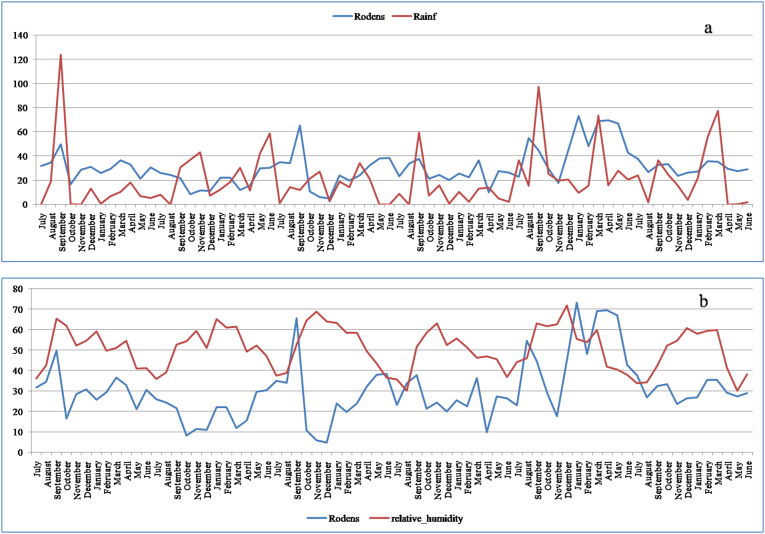

Most vector-borne diseases follow a seasonal change, making these diseases sensitive to climate (Gubler et al., 2001). El-Bakry et al., 1999 reported the roles of the photoperiod or water availability on the reproductive status of Meriones shawi in the desert-dwelling. The host density can also be sensitive to climate (Chaves and Pascual, 2006). Fig. 4 (a & b) shows the seasonal rodents density associated with maximum, minimum, and average temperatures from July 2009 to June 2015 in the case study. Generally, the evolution of the rodents shows a peak in March–April (Fig. 4). This evolution depicts an increasing trend of rodents' density in the studied area. One may notice certain elasticity for the average temperature (Fig. 4). Rodent-borne diseases are less directly affected by temperature, while the transmission of the disease depends on environmental conditions and available food (Gubler et al., 2001).

Fig. 4.

Seasonal rodents associated with maximum and minimum temperatures from July 2009 to June 2015. Data source: Talmoudi et al. (2017).

For cutaneous Leishmaniasis, climate affects the transmission dynamics since the vector density depends on climate variability, which gives it the character of seasonality (Chaves and Pascual, 2006). Fig. 5 shows the seasonal rodents associated with the rainfall and relative humidity from July 2009 to June 2015 in the the case study area. As stated above, the rodent density depends on various climatic factors, but, specifically, the association of rodents with rainfall is average because it is not direct. The rodents are sensitive to food favored by the rainfall. For example, P. obesus is born between December and April its breeding period depends on food availability, consequently, on rainfall and stops completely in drought period (Biagi, 2004).

Fig. 5.

a, Seasonal rodents associated with the rainfall from July 2009 to June 2015. b, Seasonal rodents related to the relative humidity from July 2009 to June 2015. Data source: Talmoudi et al. (2017).

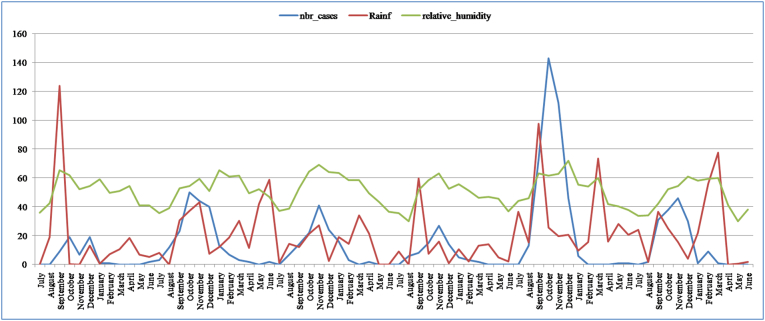

The number of ZCL cases, the rainfall, and the relative humidity seem to vary seasonally but are hardly correlated (Fig. 6). The Pearson correlation indicates a very low relationship between rodents and relative humidity (r = 0.186, a = 0.05) and an average association with rainfall (r = 0.478, a = 0.05). Rainfall was also used by Chalghaf et al. (2016) in addition to temperature as major predictors for sand flies and cutaneous Leishmaniasis cases distributions. Their Ecological Niche Modeling predicted that Gafsa, Sidi Bouzid, and Kairouan are at the highest risk of cutaneous leishmaniasis. In the same context using generalized additive model (GAM), Toumi et al. (2012) found that ZCL incidence is rising with high confidence by 1.8% in case of an increase by 1 mm and by 5% when there is a 1% increase in humidity. Chelbi et al. (2009) showed that humidity is a limiting factor for ZCL. ZCL is endemic in arid areas, and therefore, it is absent from Northern Tunisia.

Fig. 6.

Seasonal cases of ZCL associated with the relative humidity from July 2009 to June 2015. Data source: Talmoudi et al. (2017).

Fig. 7 depicts a high number of rodents in the spring season. The reservoir hosts surviving winter infect the P. papatasi during the following season (spring) and subsequently transmit the L.major (Derbali et al., 2012). In this context, Zaime et al. (1992) reported that spermatogonial and steroid are maximal in winter and spring and the sexual activity seems associated with the first rains (M. shawi in southern Morocco). Regarding the P. obesus, Gernigon et al. (2003) (cited by Bachar (2015) reported that stopping birth in the period from June to September and associated with the slowing down of male and female functions.

Fig. 7.

Seasonal rodents' density from July 2009 to June 2015 in central Tunisia. Data source: Talmoudi et al. (2017).

The rainfall (60.1 mm), the rodent density (42), and relative humidity (35.7%) are maximal in September month. These values (peaks) preceded the month with maximal recorded ZCL cases. It seems that these conditions of rainfall, relative humidity, and rodent density cause the beginning of an increased incidence of ZCL disease in the case study (Fig. 8). Using the generalized additive model (GAM) and generalized additive mixed models (GAMM), Talmoudi et al. (2017) found the same link between the used climatic variables and the increase in ZCL incidence in this period.

Fig. 8.

Seasonal change of the ZCL cases, rodents, rainfall, and relative humidity in the period 2009–2015 in the case study. Data source: Talmoudi et al. (2017).

The impacts of climate change and the human intervention on parasites hosted by reservoirs have received little attention. In this paper, a synthesis of bibliographic data on the main reservoirs of ZCL in association with the principal vector, P. papatasi, was carried out. What is evident is that the increased rainfall and suitable temperatures may favor the conditions of both rodent and vector populations (Fig. 9). However, the climatic variables cannot explain the presence of rodents, the land use (for example, agriculture and irrigation have also a considerable role in the proliferation of cutaneous leishmaniasis). Irrigation in North Africa favors the emergence of zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis (Barhoumi et al., 2016).

Fig. 9.

The impacts of climate change and land use on parasite-vector-reservoir cycle (authors).

Irrigation, land use, water management have contributed to creating favorable conditions for the proliferation of both vectors and reservoirs of the cutaneous leishmaniasis. For example in Tajikistan, irrigation has favored the conditions for the proliferation of cutaneous leishmaniasis reservoirs (Hart, 2013). Traoré et al. (2001) recorded that Dams and irrigation systems are among the factors that may have increased the risk of parasitic diseases such as CL. In addition, the newly established phoeniciculture and arboriculture in Biskra (Algeria) have caused the proliferation of several species of rodents (of a harmful nature) including Meriones shawi, a farm rodent causing damage to cereal and fruit crops (Bachar, 2015).

The presence of both, the vector (for example, P. papatasi) and the host reservoir (gerbils) favor the cycle of the leishmaniasis disease (ZCL). This was confirmed by Yaghoobi-Ershadi et al. (1996).

Regarding the control strategies, vector control is the most effective method to control the transmission of ZCL (Derbali et al., 2014). However, biological control research can be a very effective second step with caution in introducting predators and their legal protection. This can reduce the number of rodents and thus reduce the risk of transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis agents. Among the animal species that are considered predators, we quote, the predators of the arid zones focus on this neglected disease, Raptors, Fox, Horned Viper, Fennec, Sand cat, Owl…

6. Conclusion

In countries where ZCL is endemic, this disease has become a major public health problem. As mentioned above, in many studies, P. papatasi transmits L.major from Meriones shawi (the main reservoir) in the studied countries which causes the ZCL. In order to update the ZCL distribution at the MENA region, a map of the distribution of the potential hosts and the main vector P. papatasi was carried out. The findings of this study show for the PO, a high density between Palestine and Jordan, and in the north of Algeria and Central Tunisia followed by Morocco, Libya, and Egypt. However, the ZCL vector is mainly active in the north of the MENA countries with a high density observed in Morocco, Libya, and Palestine-Jordan. The associations between PO and MS allow observing a high density in southeastern Morocco and the northern parts of Algeria and Central Tunisia. In regards to the relationship between P. papatasi and PO, a high density was recorded in the southeastern of Morocco, the northern side of Algeria, Libya, Central Tunisia, and Palestine. Finally, for the correlation between the density of P. papatasi and MS, Morocco presents a very high risk followed by Algeria and Tunisia. For the associations between rodents and climate in the case study from Tunisia, the evolution of the rodents shows a peak in March–April. It is associated with rainfall and relative humidity. In regards to the number of ZCL cases, the rainfall, and the relative humidity seem to vary seasonally, but are hardly correlated. The results also depict that when rainfall, rodent density, and relative humidity are maximal in September, they may cause the beginning of an increased incidence of ZCL disease in the case study.

This review gives various knowledge of rodents and vectors linked to cutaneous leishmaniasis in all countries where MS and PO are present. These countries showed a high prevalence of ZCL. The international control programs can use the obtained findings to decrease the ZCL prevalence. In additions, decreasing the number of hosts and vectors and increasing the awareness level of the local population can also be used.

Ethics approval

We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

Competing interests

I declare no competing interests exist.

Funding source

I received no specific funding for this work.

Contributor Information

Ahmed karmaoui, Email: a.karmaoui@umi.ac.ma.

Denis Sereno, Email: denis.sereno@ird.fr.

References

- Abdel-Dayem M.S., Annajar B.B., Hanafi H.A., Obenauer P.J. The potential distribution of Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Libya based on ecological niche model. J. Med. Entomol. 2012;49(3):739–745. doi: 10.1603/ME11225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshar A.A., Rassi Y., Sharifi I., Abai M., Oshaghi M., Yaghoobi-Ershadi M., et al. Susceptibility status of Phlebotomus papatasi and P. sergenti (Diptera: Psychodidae)to DDT and deltamethrin in a focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis after earthquakestrike in Bam, Iran. Iran J. Arthropod. Borne Dis. 2011;5(2):32. PMCID: PMC3385580. PMID: 22808416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R.M., Loutfy N.F., Awad O.M., Suliman N.K. Bionomics of phlebotomine sandfly species in West Alexandria, Egypt. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016;4:349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Alten B., Maia C., Afonso M.O., Campino L., Jiménez M., González E.…Toty C. Seasonal dynamics of phlebotomine sand fly species proven vectors of Mediterranean leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvar J., Velez I.D., Bern C., Herrero M., Desjeux P., Cano J.…WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annajar B.B. Keele University; UK: 1999. Epidemiology of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Libya.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259181507Annajar-PhD-thesis-LQ PhD Thesis. 189 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Aoun K., Bouratbine A. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in North Africa: a review. Parasite. 2014;21 doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford R.W. The leishmaniases as emerging and reemerging zoonoses. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000;30:1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford R.W., Chance M.L., Ebert F., Schnur L.F., Bushwereb A.K., Drebi S.M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Libyan Arab Republic: distribution of the disease and identity of the parasite. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1976;70(4):401–409. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1976.11687139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford R.W., Schnur L.F., Chance M.L., Samaan S.A., Ahmed H.N. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Libyan Arab Republic: preliminary ecological findings. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1977;71(3):265–271. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1977.11687190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachar M.F. Université Mohamed Khider-Biskra; 2015. Contribution à l’étude bioécologique des rongeurs sauvages dans la région de Biskra. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Barhoumi W., Fares W., Cherni S., Derbali M., Dachraoui K., Chelbi I.…Zhioua E. Changes of sand fly populations and Leishmania infantum infection rates in an irrigated village located in arid Central Tunisia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13(3):329. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basuony D.M.I. 2000. Ecological Survey of Burullus Nature Protectorate. [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S. Nouveau foyer de leishmaniose cutanée à M’sila (Algérie). Infection naturelle de Psammomys obesus (Rodentia, Gerbillidae) Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Fil. 1983;76(2):146–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S. Découverte d'un Meriones shawi (Rongeur, Gerbillidé) naturellement infesté par Leishmania dans le nouveau foyer de leishmaniose cutanée de Ksar Chellala (Algérie) Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1986;79(5):630–633. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ismail R., Ben Rachid M.S., Gradoni L., Gramiccia M., Helal H., Bach-Hamba D. La leishmaniose cutanée zoonotique en Tunisie. Etude du réservoir dans le foyer de Douara. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 1987;67(4):335–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmahdi-Tabet F., Bouderoua K., Benmahdi T., Ammam A. The effect of introducing Mustela nivalis to control the reservoirs of zoonotic cutaneous Leishmaniasis at Ain Skhouna in Algeria. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2017;11(3):58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis I., De Brouwere V., Ameur B., El Idrissi Laamrani A., Chichaoui S., Hamid S., Boelaert M. Control of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major in South-Eastern Morocco. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2015;20(10):1297–1305. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagi T. Animal Diversity Web. 2004. Psammomys obesus.http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Psammomys_obesus/ (On-line) Accessed January 26, 2018 at. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G., Martin L., Maurice A. The Gerbille Meriones shawi as a reservoir of Q fever infection in thé Goulimine region of Morocco. CR Acad. Sci. 1947;224(23):1673–1674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudrissa A. 2005. Étude éco-épidémiologique de la leishmaniose cutanée dans la wilaya de M’Sila. thèse de Magister, Algérie. [Google Scholar]

- Boudrissa A., Cherif K., Kherrachi I., Benbetka S., Bouiba L., Boubidi S.C.…Harrat Z. Extension de Leishmania major au nord de l'Algérie. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 2012;105(1):30–35. doi: 10.1007/s13149-011-0199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boufermes R., Richard N., Le Moguen K., Amirat Z., Khammar F., Kottler M.L. Seasonal expression of KiSS-1 and the pituitary gonadotropins LHβ and FSHβ in adult male Libyan jird (Meriones libycus) Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2014;147(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S., Guernaoui S., Pesson B., Boumezzough A. Seasonal fluctuations of phlebotomine sand fly populations (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the urban area of Marrakech, Morocco. Acta Trop. 2005;95(2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S., Neffa M., Pesson B., Boumezzough A. Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of southern Morocco: results of entomological surveys along the Marrakech–Ouarzazat and Marrakech–Azilal roads. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2010;104(2):163–170. doi: 10.1179/136485910X12607012374235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S., Kasbari M., El Mzabi A., Boumezzough A. Epidemiological investigation of canine leishmaniasis in Southern Morocco. Adv. Epidemiol. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/104697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S., Kahime K., Samy A.M., Salem A.B., Boumezzough A. Species composition of sand flies and bionomics of Phlebotomus papatasi and P. sergenti (Diptera: Psychodidae) in cutaneous leishmaniasis endemic foci, Morocco. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1343-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalghaf B., Chlif S., Mayala B., Ghawar W., Bettaieb J., Harrabi M.…Salah A.B. Ecological niche modeling for the prediction of the geographic distribution of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016;94(4):844–851. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves L.F., Pascual M. Climate cycles and forecasts of cutaneous leishmaniasis, a nonstationary vector-borne disease. PLoS Med. 2006;3(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelbi I., Derbali M., Al-Ahmadi Z., Zaafouri B., El Fahem A., Zhioua E. Phenology of Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) relative to the seasonal prevalence of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Central Tunisia. J. Med. Entomol. 2007;44(2):385–388. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/44.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelbi I., Kaabi B., Bejaoui M., Derbali M., Zhioua E. Spatial correlation between Phlebotomus papatasi Scopoli (Diptera: Psychodidae) and incidence of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia. J. Med. Entomol. 2009;46(2):400–402. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Daly S. Spatial distribution of a leaf-eating Saharan gerbil (Psammomys obesus) in relation to its food. Mammalia. 1974;38(4):591–603. doi: 10.1515/mamm.1974.38.4.591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delanoe P. The Merion, reservoir of Moroccan Spirochaete, S. hispánica var. marocana. CR Acad. Sci. 1931;192(14) [Google Scholar]

- Derbali M., Chelbi I., Ahmed S.B.H., Zhioua E. Leishmania major Yakimoff et Schokhor, 1914 (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) chez Meriones shawi Duvernoy, 1842 (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 2012;105(5):399–402. doi: 10.1007/s13149-012-0259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbali M., Polyakova L., Boujaâma A., Burruss D., Cherni S., Barhoumi W.…Zhioua E. Laboratory and field evaluation of rodent bait treated with fipronil for feed through and systemic control of Phlebotomus papatasi. Acta Trop. 2014;135:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diatta G., Souidi Y., Granjon L., Arnathau C., Durand P., Chauvancy G.…Trape J.F. Epidemiology of tick-borne borreliosis in Morocco. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doha S.A., Samy A.M. Bionomics of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the province of Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105(7):850–856. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762010000700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokhan M.R. Seventh of April University; Zawiya, Libya: 2008. Epidemiology of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Surman, Subratah and Al-Ajaylat Districts. Doctoral dissertation, M. Sc. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Dokhan M.R., Kenawy M.A., Doha S.A., El-Hosary S.S., Shaibi T., Annajar B.B. Entomological studies of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in relation to cutaneous leishmaniasis transmission in Al Rabta, North West of Libya. Acta Trop. 2016;154:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl T. The Travelling Naturalist. 2006. Morocco in spring. February 2006. Trip Report. [Google Scholar]

- Echchakery M., Boussaa S., Ouanaimi F., Boumezzough A. 2017. The Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Rodent Species, Potential Reservoir Hosts of Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- El Mezouari E., El Farouki A., Hocar O., Akhdari N., Amal S., Moutaj R. Cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major in the area of Tamezmoute (Morocco): prospective study of 23 cases. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2015;3(2):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bakry H.A., Zahran W.M., Bartness T.J. Control of reproductive and energetic status by environmental cues in a desert rodent, Shaw’s jird. Physiol. Behav. 1999;66(4):657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(98)00344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbihari S., Kawasmeh Z.A., Al-Naiem A., Al-Atiya S. Leishmania infecting man and wild animals in Saudi Arabia. 3. Leishmaniasis in Psammomys obesus Cretzschmar in Al-Ahsa oasis. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1987;38(2):89–92. PMID:3306886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Buni A.A., Refai A.G. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) fauna survey in Tripoli and Zwara, Libya (abstr.) Arch. Inst. Pasteur Tunis. 2005;82:15. [Google Scholar]

- Fichet-Calvet E., Jomaa I., Giraudoux P., Ashford R.W. Estimation of fat sand rat Psammomys obesus abundance by using surface indices. Acta Theriol. 1999;44(4):353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Fichet-Calvet E., Jomaa I., Zaafouri B., Ashford R.W., Ben-Ismail R., Delattre P. The spatiotemporal distribution of a rodent reservoir host of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000;37(4):603–615. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2664.2000.00522.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fichet-Calvet E., et al. Leishmania major infection in the fat sand rat Psammomys obesus in Tunisia: interaction of host and parasite populations. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2003;97(6):593–603. doi: 10.1179/000349803225001517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foroutan M., Khademvatan S., Majidiani H., Khalkhali H., Hedayati-Rad F., Khashaveh S., Mohammadzadeh H. Prevalence of Leishmania species in rodents: a systematic review and meta-analysis in Iran. Acta Trop. 2017;172:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernigon T., et al. 2003. Etude histologique, morphométrique et immuno-histo-chimique des vésicules séminales du Mérione de Libye (Meriones libycus) 22p. [Google Scholar]

- Ghawar W., Toumi A., Snoussi M.A., Chlif S., Zâatour A., Boukthir A.…Ben-Salah A. Leishmania major infection among Psammomys obesus and Meriones shawi: reservoirs of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sidi Bouzid (Central Tunisia) Vector-Borne Zoonot. Dis. 2011;11(12):1561–1568. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghawar W., Attia H., Bettaieb J., Yazidi R., Laouini D., Salah A.B. Genotype profile of Leishmania major strains isolated from Tunisian rodent reservoir hosts revealed by multilocus microsatellite typing. PLoS One. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghawar W., Zaâtour W., Chlif S., Bettaieb J., Chalghaf B., Snoussi M.A., Ben Salah A. Spatiotemporal dispersal of Meriones shawi estimated by radio-telemetry. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2015;2:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gholamrezaei M., Mohebali M., Hanafi-Bojd A.A., Sedaghat M.M., Shirzadi M.R. Ecological niche modeling of main reservoir hosts of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Acta Trop. 2016;160:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Barroso D., Herrador Z., San Martin J.V., Gherasim A., Aguado M., Romero-Maté A.…Benito A. Spatial distribution and cluster analysis of a leishmaniasis outbreak in the South-Western Madrid region, Spain, September 2009 to April 2013. Eurosurveillance. 2015;20(7):21037. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.7.21037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham R.W. Late Pleistocene faunal changes as a guide to understanding effects of greenhouse warming on the mammalian fauna of North America. Glob. Warm. Biol. Divers. 1992:76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Graham R.W., Grimm E.C. Effects of global climate change on the patterns of terrestrial biological communities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1990;5(9):289–292. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(90)90083-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham R.W., Lundelius E.L., Graham M.A., Schroeder E.K., Toomey R.S., Anderson E.…Guthrie R.D. Spatial response of mammals to late quaternary environmental fluctuations. Science. 1996;272(5268):1601–1606. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D.J., Reiter P., Ebi K.L., Yap W., Nasci R., Patz J.A. Climate variability and change in the United States: potential impacts on vector-and rodent-borne diseases. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl. 2):223. doi: 10.1289/ehp.109-1240669. PMCID: PMC1240669. PMID: 11359689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart D.T., editor. Leishmaniasis: The Current Status and New Strategies for Control: Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute, Zakynthos (Greece), 1987. Vol. 171. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R.J., Graham C.H. The ability of climate envelope models to predict the effect of climate change on species distributions. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2006;12(12):2272–2281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01256.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim E.A., Mustafa M.B., Al Amri S.A., AlSeghayer S.M., Hussein S.M., Gradoni L. Meriones libycus (Rodentia: Gerbillidae), a possible reservoir host of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Riyadh province, Saudi Arabia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994;88(1):39. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90488-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadian E., Dehestani M., Nadim A., Rassi Y., Tahvildar-Bidruni G., Seyedi-Rashti M., et al. Confirmation of Tatera indica (Rodentia: Gerbilldae) as the main reservoir host of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in the west of Iran. Iran. J. Public Health. 1998;27(1–2):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson O., Marais S., Walters J., van der Merwe E.L., Alagaili A.N., Mohammed O.B.…Kotzé S.H. The distribution of mucous secreting cells in the gastrointestinal tracts of three small rodents from Saudi Arabia: Acomys dimidiatus, Meriones rex and Meriones libycus. Acta Histochem. 2016;118(2):118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmaoui Ahmed. Seasonal distribution of Phlebotomus papatasi, vector of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Acta Parasitologica. 2020;65:585–598. doi: 10.2478/s11686-020-00201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe C. MOROCCO. 26 APRIL – 7 MAY 2017. 2017. www.birdquest-tours.com BirdQuest Tour Report: Morocco 2017.

- Khammar F., Gernigon-Spychalowicz T. Two rodents in Ben-Abbes with predisposition to diabetes (film) Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 1997;105(S 03):84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Khemiri H., Jrijer J., Neifar L., Nouira S. A survey study on the helminth parasites of two wild jirds, Meriones shawi and M. libycus (Rodentia: Gerbillinae), in Tunisian desert areas. The European Zoological Journal. 2017;84(1):303–310. doi: 10.1080/24750263.2017.1307462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimutai A., Ngure P.K., Tonui W.K., Gicheru M.M., Nyamwamu L.B. Leishmaniasis in northern and Western Africa: a review. Afr J Infect Dis. 2009;3(1):14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lahouiti K., Maniar S., Bekhti K. Seasonal fluctuations of phlebotomines sand fly populations (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the Moulay Yacoub province, Centre Morocco: effect of ecological factors. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;7(11):1028–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Malek M.A., Hammani A., Beneldjouzi A., Bitam I. Enzootic plague foci, Algeria. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;4:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoumeh A., Kourosh A., Mohsen K., Hossein M.M., Qasem A., Djaefar M.F.M.…Tahereh D. Laboratory based diagnosis of leishmaniasis in rodents as the reservoir hosts in southern Iran, 2012. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014;4:S575–S580. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014APJTB-2014-0199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell M.A., Rafati S., Ramalho-Ortigao M., Salah A.B. Leishmaniasis: Middle East and North Africa research and development priorities. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes J.A., Ferreira E.D.C., Andrade-Filho J.D., Sousa A.M.D., Morais M.H.G., Rocha A.M.S.…Freitas C.R. An integrated approach using spatial analysis to study the risk factors for Leishmaniasis in area of recent transmission. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/621854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsy T.A., Sabry A.H., Rifaat M.M., Wahba M.M. Psammomys obesus Cretzschmar, 1828 and zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 1996;26(2):375–381. (PMID:8754646) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa B.H., Souha B.A., Sabeh F., Noureddine C., Riadh B.I. Evidence for the existence of two distinct species: Psammomys obesus and Psammomys vexillaris within the sand rats (Rodentia, Gerbillinae), reservoirs of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2006;6(4):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshaghi M.A., Rassi Y., Tajedin L., Abai M.R., Akhavan A.A., Enayati A., Mohtarami F. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in the populations of great gerbils, Rhombomys opimus, the main reservoir of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Acta Trop. 2011;119(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouanaimi F., Boussaa S., Boumezzough A. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of Morocco: results of an entomological survey along three transects from northern country. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2015;5(4):299–306. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60787-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzaouit A. The situation of rodents in Morocco. National seminar on monitoring and the fight against rodents. Marrakech. 2000:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi P., Mauricio I., Aransay A.M., Miles M.A., Ready P.D. First detection of Leishmania major in peridomestic Phlebotomus papatasi from Isfahan province, Iran: comparison of nested PCR of nuclear ITS ribosomal DNA and semi-nested PCR of minicircle kinetoplast DNA. Acta Trop. 2005;93(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petter F. Répartition géographique et écologie des rongeurs désertiques de la région paléartique. Mammalia. 1961;25:1–219. [Google Scholar]

- Petter F. 1988. Epidémiologie de la leishmaniose cutanée dans le sud du Maroc et dans le sud-est de l’Arabie. Séance du 18 février 1988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo J.A.R. Leishmaniasis in the world health organization eastern mediterranean region. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2010;36:S62–S65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasi Y., Jalali M., Javadian E., Motazedian M.H. 2001. Confirmation of Meriones libycus (Rodentia; Gerbillidae) as the Main Reservoir Host of Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Arsanjan, Fars Province, South of Iran (1999–2000) [Google Scholar]

- Rioux J.A., Petter F., Akalay O., Lanotte G., Ouazzani A., Seguignes M., Mohcine A. Meriones shawi (Duvernoy, 1842) [Rodentia, Gerbillidae] réservoir de Leishmania major, Yakimoff and Schokhor, 1914 [Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae]au Sud Maroc. CR des Acad. Sci. Sér. III. 1982;294(11):515–517. Sciences de la vie. PMID:6807510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux J.A., Ashford R.W., Khiami A. Ecoepidemiology of leishmaniases in Syria. 3. Leishmania major infection in Psammomys obesus provides clues to life history of the rodent and possible control measures. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1992;67(6):163–165. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1992676163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahraoui I., Nasri B. Université des Frères Mentouri Constantine. 2015. Contribution à l’étude de la biodiversité des Phlébotomes (Diptera: Psychodidae) dans la région de Constantine. Master dissertation. 77p. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba E.K., Disi A.M., Ayed R.E., Saleh N., Al-Younes H., Oumeish O., Al-Ouran R. Rodents as reservoir hosts of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Jordan. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1994;88(6):617–622. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samy A.M., Doha S.A., Kenawy M.A. Ecology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sinai: linking parasites, vectors and hosts. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109(3):299–306. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276130426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawalha S.S., Ramlawi A., Sansur R.M., Salem I.M., Amr Z.S. Diversity, ecology, and seasonality of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of the Jenin District (Palestinian Territories) J. Vector Ecol. 2017;42(1):120–129. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y., Jacobson R.L. Sugar meals and longevity of the sandfly Phlebotomus papatasi in an arid focus of Leishmania major in the Jordan Valley. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1999;13(1):65–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1999.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settaf A., Khalil B., Mrhari I., Berrada Y., Cherrah Y., Slaoui A., Hassar M. Hypertension and insulin resistance in Meriones Shawi. Characterization of stages in development of diabetes syndrome. Biolog. Santé. 2000;1:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stoetzel E., Cornette R., Lalis A., Nicolas V., Cucchi T., Denys C. Systematics and evolution of the Meriones shawii/grandis complex (Rodentia, Gerbillinae) during the late quaternary in northwestern Africa: exploring the role of environmental and anthropogenic changes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2017;164:199–216. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabit A.U., Abdel Qader A.A., El-Buni A.A. Sand fly species in Sayad and Janzour, Libya (abstr.) Arch. Inst. Pasteur Tunis. 2005;82:123. [Google Scholar]

- Talbi F.Z., El Ouali Lalami A., Janati Idrissi A., Sebti F., Faraj C. Leishmaniasis in Central Morocco: seasonal fluctuations of phlebotomine sand fly in Aichoun locality, from Sefrou province. Pathol. Res. Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/438749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmoudi K., Bellali H., Ben-Alaya N., Saez M., Malouche D., Chahed M.K. Modeling zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis incidence in Central Tunisia from 2009-2015: forecasting models using climate variables as predictors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thévenot M., Aulagnier S. Updating the list of mammals Wild Morocco. Go-South Bull. 2006;3:6–9. French. [Google Scholar]

- Tomás-Pérez M., Khaldi M., Riera C., Mozo-León D., Ribas A., Hide M.…Fisa R. First report of natural infection in hedgehogs with Leishmania major, a possible reservoir of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Algeria. Acta Trop. 2014;135:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toumi A., Chlif S., Bettaieb J., Alaya N.B., Boukthir A., Ahmadi Z.E., Salah A.B. Temporal dynamics and impact of climate factors on the incidence of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Central Tunisia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traoré K.S., Sawadogo N.O., Traore A., Ouedraogo J.B., Traoré K.L., Guiguemdé T.R. Preliminary study of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the town of Ouagadougou from 1996 to 1998. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 2001;94(1):52–55. 11346985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2010. Control of the Leishmaniasis: Report of a Meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniasis. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2010. Report on the Programme Managers Meeting on Leishmaniasis Control, Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, 27–29 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi-Ershadi M.R., Akhavan A.A., Mohebali M. Meriones Iibycus and Rhombomys opimus (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) are the main reservoir hosts in a new focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996;90(5):503–504. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(96)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaime A., Laraki M., Gautier J.Y., Garnier D.H. Seasonal variations of androgens and of several sexual parameters in male Meriones shawi in southern Morocco. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1992;86(2):289–296. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(92)90113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zouirech M., Belghyti D., El Kohli M., Faraj C. Entomological investigation of an emerging leishmaniasis focus in Azilal province, Morocco. Pak. Entomol. 2013;35:11–15. [Google Scholar]