Summary box.

A good place to start the decolonisation of global health is the decolonisation of academic publishing spaces, namely spaces where dissemination of ‘acceptable’ knowledge is enabled and ‘epistemic privilege’ is sanctioned.

Decolonising academic publishing will require meta-knowledge and transparency about the assumptions, frames-of-reference, representation and power and privilege of authors and relevant institutions.

Such meta-cognition can be based on viewing all global health research, policy and implementation activities as transactions across a power structure.

Transparency will require purpose-built tools for reflexivity and ‘soft’ mixed metrics (an example of such a tool is discussed) for comparability and gauging progress on decolonisation.

Detailed knowledge about ontology of power-structures traversed and intersectional identities represented by each global health transaction should be made explicit by visual and/or narrative tools (I present some examples here).

Journals publishing research and reports about ‘global’ health should make room for publication of communications from alternate epistemic standpoints and de-emphasise traditional hierarchies of evidence

Introduction

The last few years have witnessed a renewed consciousness and increasing calls for ‘decolonising’ global health.1–3 The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with this increased awareness and demand for change by exposing the deep-rooted inequities, biases, elitism and racism that plague global public health.4 Building on this sentiment, there have been calls for putting rhetoric into action towards achieving meaningful decolonisation of global health.5 6

There is now an ongoing debate about the best strategies to eventualise such decolonisation. In this debate, positions may be classified into four approaches. These include the ‘metrics-oriented’ approach that stipulates the need for metrics to aid the process of decolonisation5; the ‘pragmatic’ approach that demands broad based, though arguably enforceable changes that cut across the global health landscape6; the ‘epistemology-oriented’ approach that situates the decolonising endeavour within an established framework of decolonial philosophy,7 and the ‘partnerships-oriented’ approach that calls for power and privilege sharing across the global health landscape.8 9 Each approach has its particular strengths just as each has its own blind spots.

Sustainable progress towards decolonisation will require some form of measurement.5 However, such metrics would have to be carefully crafted and consist of a mix of qualitative and quantitative elements—all designed with a view to engage creators and users of knowledge in meaningful and sustained reflexivity.10 Epistemology-oriented approaches7 correctly identify the root cause of colonialism and dominance in patterns of thought. But embedding the decolonisation discourse within paradigms of decolonial philosophy laden with complex language and terminology may make the discourse inaccessible to the majority of people disenfranchised and affected by colonialism. By shifting the power of analysis back to the erudite elite, epistemology-oriented approaches may inadvertently exclude the masses, and can also paralyse direct decolonising action by extending the decolonisation process towards an infinite horizon.

The pragmatic approach6 realises the urgency of decolonising action. However, this urgency leads to proposals for actions that may be difficult or impossible to enforce. This can have the unwanted effect of shifting focus away from immediately attainable targets. Finally, proponents of a partnerships-based approach8 9 propose North-South partnerships and a ‘leaning-out’ strategy to distribute power and dilute privilege. This approach, while noble, seems to miss the fact that, at present, all incentives are aligned against meaningful partnerships and power-sharing. The few constraints enforced by academic publishing (and some donors) like inclusion of authors/partners from the Global South, can easily be seen as tokenism. Moreover, partnerships are often limited to very few ‘elite’ institutions or usual partners in ‘low-income and middle-income countries’ and other disadvantaged contexts.

In this article, I will describe a strategy that draws on the strengths of all of the above approaches; with a focus on academic publishing.11 In their roles as gatekeepers of knowledge dissemination, academic publishers are influential purveyors of credibility, power and privilege in academia and health policy circles.12 The academic publication space needs to be sanitised early if we are to achieve sustained equitable change in global health discourse and knowledge.

This exposition is grounded in the belief that processes that enforce and make explicit deep critical reflexivity,13–15 are likely to be crucial to mainstreaming marginalised voices and ‘othered’ ways of knowing. Below, I outline a process that can serve as a practical template for transforming academic publishing in global health into a more equitable and representative system.

Transactions across a power differential

The basic drivers and origins of power can be understood in terms of social transactions, shaped by individual needs and the social environment (ecology). The notion of fungibility of power and its emergence from social transactions is very well developed in the context of ‘Power Basis Theory’.16 The published literature in global health can be seen as resulting from three types of social transactions (or exchanges) between those with the power to study and/or influence and those who are considered the subjects of these social transactions: (1) research/investigative transactions; (2) project/implementation transactions and (3) health policy transactions. By reflecting on the type of transaction one engages in, one gains a better understanding of the limits of one’s influence and the potential for harm to others. Making such reflection explicit in any academic communication through a standardised transparency instrument or matrix, knowledge creators can make transparent many of their underlying assumptions/heuristics for their readers. I present a template for such a tool below.

Metadata: the transparency matrix

Reporting of each global health transaction should be associated with metadata that make explicit the position of that particular transaction. I build on the ideas of Seye Abimbola17 18 and others19 in highlighting a seven-dimensional vector space (table 1) likely to be most consequential for reflexivity.

Table 1.

The transparency matrix

| Identity vector | Reflection/ narrative (how/why?) |

|

| Dimension | ||

| Pose | Epistemic positionality of the autho—source of the framework employed to argue about rationale and causal relationships:

|

|

| Position | Author’s position within the power structure of the transaction:

|

|

| Voice | Whose voice has primacy in the design of this transaction?

|

|

| Gaze | Who is this communication primarily addressed to?

|

|

| Lens | Primary analytical lens used to draw conclusions:

|

|

| Slice | No. of Intersectional Identities included (estimate)_____ Total no. of Intersectional Identities potentially affected (approx.) (proportion: a real number between 0 and 1) |

|

|

Taste

(Reality Check) |

User-centredness of research findings/user-experience (UX) resulting from the Project/Policy Implementation (Likert scale):

|

|

Transparency matrix is a data structure designed to elicit reflection in the form of a narrative justification along seven dimensions. Each narrative is indexed by a numerical value assigned in the relevant row of the ‘identity vector’ according to the description above. This should be required to be completed by each author in order to encourage reflexivity. The data structure can be used as a dictionary or hash, an identity vector or a text corpus for any subsequent computational analysis. More importantly, it can be used as a tool for qualitative analysis of value judgments.

NGO, Non-governmental organisation; UN, United Nations; WHO, World Health Organisation.

As a carefully crafted ‘data structure’, this instrument contains both quantitative and qualitative inputs (and is therefore open to interpretation and evaluation from varied standpoints). These transparency matrices should be freely available and linked to each publication as metadata. The ability to extract each publication’s identity vector as well as narrative reflection can help appropriately situate each writing within the broader landscape of relevant knowledge. As the world increasingly becomes data-driven and machine-learning evaluated, it is essential to anticipate issues of bias and fairness, and proactively devise ways to counter existing and entrenched biases in data collection methods.20 21 Logging transparent data, in deliberately designed data structures, is likely to help address harmful and ethically dubious recommendations and conclusions based on biased data.21 22

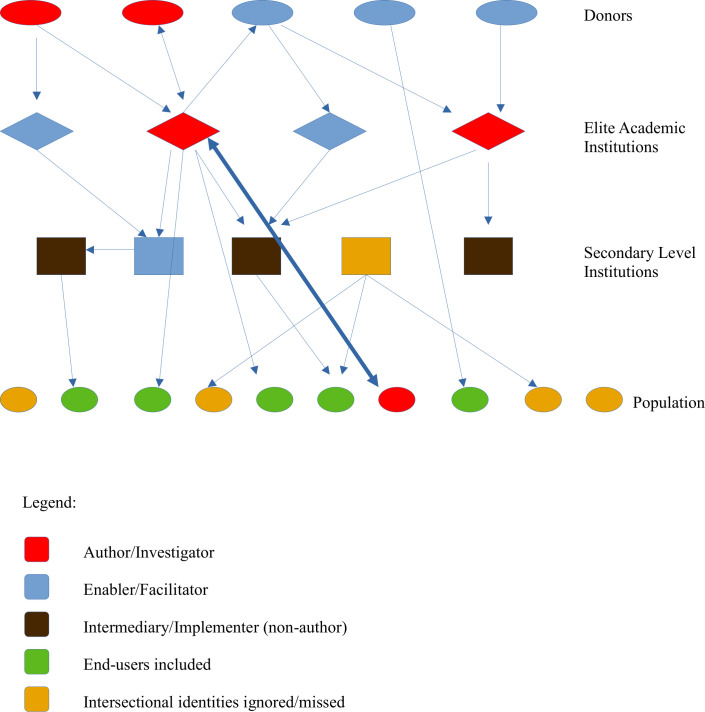

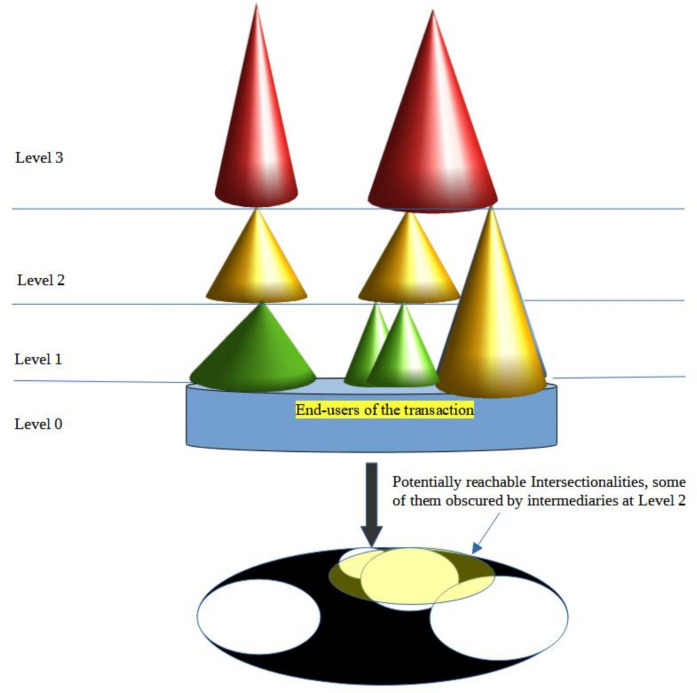

Metrics are a contested tool in global health.23 Often wrongly assumed to be value-neutral, numerical metrics are in reality a product of underlying norms, values and assumptions.24 25 Distortion during data collection24 and the ‘arithmetic gymnastics’25 sometimes used to fit data to a metric, often obscure ‘on-ground’ reality.26 27 In not being end-user responsive, the data used to derive metrics are prone to being ‘gamed’.28 Further distortions are introduced during visualisation and storytelling.24 The soft metrics described here are designed with a visualisation-first and narrative-first point of view. While there is a quantitative index (identity vector) linked to the narrative (table 1), the tool is open to interpretation, stressing a data-first rather than a tool-first approach. The visual tools have redundancy built in. For instance, ontology is exposed from both a discrete/graph (figure 1) and continuous/cascade (figure 2) perspective. Reflection about intersectionality is also built-in. Most importantly, I present these tools/metrics as an examplar for reflexivity rather than a prescriptive template.

Figure 1.

Directed Graph of Ontology: Shown here is an example of how a directed ontological graph could look like. Ontologies (the nature of entities in a transaction and relationships between them) can be visually examined using a directed graph. Shapes indicate the hierarchical status and colour-coding indicates the level of inclusion/exclusion. Ontologies can make explicit the validity of assumptions about actors and relationships, identify bottlenecks and indicate excluded intersectional identities. This graphic can be modified to elucidate the relationships between epistemological entities (concepts) and how different levels of concepts validate/nullify ensuing entities and which intersectional identities are rendered invalid in a given scheme of reasoning.

Figure 2.

The Cascading Cones Chart: Cone apices represent individual stakeholders. The base of each cone represents the sphere of direct influence of the given stakeholder in the current transaction. The height (or depth) of each cone represents the levels across which that influence extends. The cylinder represents the end-users of the current transaction. The interface of the cones at the bottom of the cascade with the cylinder represents the intersectional identities touched by the given transaction. The projection of this interface onto the ellipse at the bottom shows population sections (or union of intersectional identities) covered by the given transaction (white ellipses) as well as the blind spots or intersectional identities missed (black region).

Ontology, intersectionality and cascading cones of influence

Ontology refers to social entities and their relationships and how relationships and entities ‘create’ each other. No research, implementation or policy transaction should be considered valid unless it can be situated appropriately in the landscape of power relations. Power ontologies directly affect the pose, gaze, voice, position and lens that frame a given transaction in global health.

Intersectionality seeks to describe social identities as products of differential situation inside a power landscape.29 For instance, the intersectional identity of a person who is a ‘woman AND domestic worker AND living on three dollars a day AND living in a village near a large city in southern Pakistan’ is very different from that of a ‘woman AND farm worker AND on subsistence living AND situated in a ‘remote’ rural area in northwestern Pakistan’. These two individuals may have very different life experiences and health and social needs, although conventionally, in a global health context, they would often be lumped into a single category of ‘poor working women in rural Pakistan’. Intersectionality can offer a valid and legitimate basis for defining the true scope of a ‘global’ health research project. Instead of making universal generalisations, the domain of applicability can be better defined by transparently reflecting about the universe of all the potential intersectional identities within the scope of work and the ‘slice’ of this universe that is being evaluated/studied (table 1).

Ontologies can be examined and represented by a directed graph or flowchart (figure 1) where nodes represent stakeholder entities and end-user intersectional identities. The arrows represent the direction of influence in the context of each transaction. Visualisation of the ontology can make the underlying context and power relations explicit and guide in identifying valid conclusions and recommendations. Ontology can also be visualised in a cascading cones chart (CCC) (figure 2).

CCC can also help to more intuitively understand the intersectionality of end-users at the interface with power structures as well as the intersectional identities overlooked or missed by a given transaction. Thinking through the CCC can further shed light on the level(s) at which the transaction interface should be situated as some intersectional identities within the population of interest may be obscured by limitations or biases particular to the intermediaries in the cascade of influence (figure 2).

Publishing methodologies from alternate epistemic standpoints

If progress is to be made towards epistemic justice in global health, we need to make room for alternate ways of knowing and evaluating at the highest echelons of credibility.18 Mainstream journals publishing academic research with their editorial and peer review structures often function as gatekeepers for what qualifies as ‘admissible’, ‘high-quality’ research and knowledge. However, in judging validity and value through a one-dimensional Eurocentric epistemic lens,30 such gatekeepers commit and perpetuate epistemic injustice against knowledge-producers expounding from alternate ways of knowing and indigenous epistemologies.18 31 This leads to testimonial injustice32 namely exclusion of testimony that originates from alternate interpretations of how the world works.

It is essential that leading journals publishing impactful global health research make room for original research articles that explore the world from alternate epistemes. Gradual formalisation and mainstreaming of alternate ways of knowing and analysis can start with publishing ‘methodology’ or epistemology papers conceptualised and originating from their relevant locales. Bringing these methodologies to the fore can help demystify their workings for an interested practitioner in other contexts, resulting in broader dissemination, awareness and cross-fertilisation of ideas and knowledges.

In addition to requiring artifacts as metadata for context as well as logs of reflexivity, journals publishing global health research should also lower barriers to publish knowledges emanating from alternate ways of knowing and being. Dedicated space should be created in publications for these parallel logics and epistemologies and a greater number of peer-reviewers belonging to traditionally disadvantaged backgrounds should be approached, engaged and recognised. Such humility and open-mindedness are only possible when we start shifting our thinking from “hierarchies” of knowledge and evidence to “landscapes” of contextually relevant knowledge and from cliques of influence and institutional prestige and privilege to “flattened” social networks and egalitarian ontologies. The visual and narrative tools described in this work can help illuminate some of these cognitive transitions.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are often considered the highest and most pure level of scientific evidence in health and social sciences.33 34 Their strength derives from randomisation which controls confounding. However this ‘overcontrolling’ often makes these studies idealised (mis)representations of reality-in-context, by artificially dissociating them from the contextual causal substrate (‘usual care’ settings) in which the studied interventions are to be implemented.33

Many variants of RCTs such as pragmatic or adaptive designs have been recommended but they each suffer from several limitations, statistical loopholes and similar objections about which version of reality they represent.33 34 The costs associated with conducting any sizeable RCT have led to over-representation of the interests of sponsors and investigators hailing from North America, Western Europe and East Asia and shifted the power of knowledge creation decisively in favour of entities from these regions.33 As we wade into the age of pervasive and ever-proliferating real-world data and aspire for a future of personalised/individualised health for all, we may well be forced to privilege ‘real-world evidence’ over and beyond RCTs.33 35

In order to make sense of the high volume and velocity of real-world data one often needs to rely on complex algorithmic pipelines, or machine learning techniques. Yet with millions or billions of learnable parameters many of these technologies often leave little room for explaining how the algorithmic ‘oracle’ draws its inferences.36 37 It is interesting to reflect on how global human health decision-makers have greater faith in inductive bias of artificially intelligent ‘black-boxes’ of limited explainability38 39 than ‘explainably intelligent’ fellow humans with inductive biases and explainable epistemes fine-tuned over millennia of evolution-in-context.

Moving from statistical to causal inference and using a calculus of causal diagrams for reasoning40 may be a step in the direction of greater transparency, accessibility and inclusivity. Requiring each author to fill a Transparency Matrix (table 1) and publishing this as metadata with each study will likely encourage reflexivity in study design and implementation, including for RCTs when such trials are deemed necessary.

CCC (figure 2) and visual representations of ontologies (figure 1) can also be adapted to reflect and reason about sequential assumptions and correctly identify the intersectional situations where inferences may be justifiably applicable. Using simple visual tools enables a greater diversity of people to participate, weigh in and be heard. This is especially so as many indigenous ways of knowing and reasoning rely on visual artefacts and narratives to make sense of the world.41 42

Conclusion

The cognitive and philosophical underpinnings of decolonisation can only be fully uncovered by situating the epistemological and ontological analysis of health in the lived reality of people. If most actors (academic, policy, publishing, funding) have no real incentives to share power and privilege and behave in ways conducive to emancipation—then, instead of relying on the goodwill of actors, we need to deeply focus on individual elements of the system. We must create accountability checkpoints and relevant disincentives if we are to steer the current trajectory of global health to a more egalitarian one. My focus here has been on the academic publishing part of the global health system and I have argued that we need to sanitise this space as it is here that hierarchies of credibility take shape.

Any global health intervention, instead of being abstracted as a benevolent action on a population, should be analysed at a more granular level as one of three types of transactions. By uncovering the transactional nature of interventions, we are better able to expose the underlying social structure and analyse power, privilege, ontology, intersectionality and influence. I have presented a set of prototypes of mixed quantitative-narrative (table 1) and visual artefacts (figures 1 and 2) that can serve both as instruments of reflexivity as well as ‘soft metrics’ that can be tracked and analysed.

Decolonisation of global health is an enormous task. Breaking the task down to achievable milestones may be one way to approach the problem. Requiring emancipation from the cognitive substrate of dominant Eurocentric scientific paradigms, the task should first begin with gradual decolonisation of knowledge. As gatekeepers of academic knowledge generation and dissemination, academic journals can lead this effort by requiring reflexivity, transparency and accountability in the form of narrative and visual soft metrics. Journals should also allocate space and be the sounding boards for alternate ways of knowing and being. Evidence hierarchies should be flattened into evidence landscapes and assignment of credibility to evidence should be based on appropriateness to relevant contexts.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge Seye Abimbola for his deep engagement and very useful feedback in shaping the final draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @LaparoscopyFsd

Contributors: SAK is the sole author and is responsible for ideation, writing, images and submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Abimbola S, Pai M. Will global health survive its decolonisation? Lancet 2020;396:1627–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32417-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Büyüm AM, Kenney C, Koris A, et al. Decolonising global health: if not now, when? BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e003394. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence DS, Hirsch LA. Decolonising global health: transnational research partnerships under the spotlight. Int Health 2020;12:518–23. 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;74:964–8. 10.1136/jech-2020-214401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan M, Abimbola S, Aloudat T, et al. Decolonising global health in 2021: a roadmap to move from rhetoric to reform. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e005604. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oti SO, Ncayiyana J. Decolonising global health: where are the Southern voices? BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006576. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri MM, Mkumba L, Raveendran Y, et al. Decolonising global health: beyond 'reformative' roadmaps and towards decolonial thought. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006371. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abimbola S, Asthana S, Montenegro C, et al. Addressing power asymmetries in global health: imperatives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003604. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olusanya JO, Ubogu OI, Njokanma FO, et al. Transforming global health through equity-driven funding. Nat Med 2021;27:1136–8. 10.1038/s41591-021-01422-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liwanag HJ, Rhule E. Dialogical reflexivity towards collective action to transform global health. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006825. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padmalochanan P. Academics and the field of academic publishing: challenges and approaches. Pub Res Q 2019;35:87–107. 10.1007/s12109-018-09628-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw DM, Penders B. Gatekeepers of reward: a pilot study on the ethics of editing and competing evaluations of value. J Acad Ethics 2018;16:211–23. 10.1007/s10805-018-9305-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crabtree SM. Reflecting on reflexivity in development studies research. Dev Pract 2019;29:927–35. 10.1080/09614524.2019.1593319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonda N, Leder S, González-Hidalgo M, et al. Critical reflexivity in political ecology research: how can the Covid-19 pandemic transform us into better researchers? Front Hum Dyn 2021;3:41. 10.3389/fhumd.2021.652968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanson L. From reflexivity to collectivity: challenging the benevolence narrative in global health. Can Med Educ J 2017;8:e1–3. 10.36834/cmej.42021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pratto F, Lee I, Tan J. Power basis theory: a psycho-ecological approach to power. In: Dunning D, ed. Social motivation. New York, NY: Psychology Press, 2011: 191–221. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abimbola S. The foreign gaze: authorship in academic global health. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e002068. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhakuni H, Abimbola S. Epistemic injustice in academic global health. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e1465–70. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00301-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs-Huey L. The Natives Are Gazing and Talking Back: Reviewing the Problematics of Positionality, Voice, and Accountability among "Native" Anthropologists. Am Anthropol 2002;104:791–804. 10.1525/aa.2002.104.3.791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul AK, Schaefer M. Safeguards for the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning in global health. Bull World Health Organ 2020;98:282. 10.2471/BLT.19.237099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher RR, Nakeshimana A, Olubeko O. Addressing fairness, bias, and appropriate use of artificial intelligence and machine learning in global health. Front Artif Intell 2020;3:561802. 10.3389/frai.2020.561802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balayn A, Lofi C, Houben G-J. Managing bias and unfairness in data for decision support: a survey of machine learning and data engineering approaches to identify and mitigate bias and unfairness within data management and analytics systems. The VLDB Journal 2021;30:739–68. 10.1007/s00778-021-00671-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan M. The IHME in the Shifting Landscape of Global Health Metrics. Glob Policy 2019;10:S1:110–20. 10.1111/1758-5899.12605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irwin R. Imagining the postantibiotic future: the visual culture of a global health threat. Med Humanit 2020. 10.1136/medhum-2020-011884. [Epub ahead of print: 30 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erikson SL. Global health indicators and maternal health futures: the case of intrauterine growth restriction. Glob Public Health 2015;10:1157–71. 10.1080/17441692.2015.1034155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storeng KT, Béhague DP. “Guilty until proven innocent”: the contested use of maternal mortality indicators in global health. Crit Public Health 2017;27:163–76. 10.1080/09581596.2016.1259459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wendland C. Estimating death: A close reading of maternal mortality metrics in Malawi. In: Adams V, ed. Metrics: what counts in global health. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016: 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J. Improve the Design and Implementation of Metrics From the Perspective of Complexity Science Comment on "Gaming New Zealand's Emergency Department Target: How and Why Did It Vary Over Time and Between Organisations?". Int J Health Policy Manag 2021;10:273–6. 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein B. Social ontology. In: The Routledge companion to philosophy of social science. Routledge, 2016: 260–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weldon SL. Intersectionality. In: Goertz G, Amy G, eds. Politics, gender and concepts: theory and methodology. Mazur, 2008: 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borland R, Morrell R, Watson V. Southern agency: navigating local and global imperatives in climate research. Global Environmental Politics 2018;18:47–65. 10.1162/glep_a_00468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker M, Martinez-Vargas C. Epistemic governance and the colonial epistemic structure: towards epistemic humility and transformed South-North relations. Crit Stud Educ 2020;17:1–16. 10.1080/17508487.2020.1778052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bothwell LE, Greene JA, Podolsky SH, et al. Assessing the gold standard—lessons from the history of RCTs. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2175–81. 10.1056/NEJMms1604593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frieden TR. Evidence for health decision making—beyond randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med 2017;377:465–75. 10.1056/NEJMra1614394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ, et al. Real-world evidence - what is i and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med 2016;375:2293–7. 10.1056/NEJMsb1609216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holzinger A, Langs G, Denk H, et al. Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov 2019;9:e1312. 10.1002/widm.1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amann J, Blasimme A, Vayena E, et al. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020;20:1–9. 10.1186/s12911-020-01332-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angelov PP, Soares EA, Jiang R, et al. Explainable artificial intelligence: an analytical review. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2021;11:e1424. 10.1002/widm.1424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meske C, Bunde E, Schneider J. Explainable artificial intelligence: objectives, stakeholders, and future research opportunities. Inf Syst Manag 2021;9:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearl J. An introduction to causal inference. Int J Biostat 2010;6:Article 7. 10.2202/1557-4679.1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parter C, Wilson S. My research is my story: a methodological framework of inquiry told through Storytelling by a doctor of philosophy student. Qual Inq 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Litts BK, Searle KA, Brayboy BMJ, et al. Computing for all?: examining critical biases in computational tools for learning. Br J Educ Technol 2021;52:842–57. 10.1111/bjet.13059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.