Abstract

Background/Aim: Increasing economic pressure in modern healthcare necessitates an increase in efficiency in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) while maintaining high-quality outcomes. Removal of debris using pulsatile lavage (PL) during cement polymerization may considerably reduce the operative duration. However, water can penetrate the interface, resulting in impaired implant fixation. The aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of early-onset PL during bone cement polymerization on implant fixation and operative duration.

Materials and Methods: Cemented implantation of tibial trays was performed in 20 fresh-frozen human tibiae from 10 donors in a matched-pair study design in two groups: 1) PL during cement polymerization; and 2) PL after completion of the polymerization process. The cement penetration depth was analysed by computed tomography (CT), and the pull-out force was measured to evaluate primary implant fixation. The duration of the procedure was recorded for both groups.

Results: Comparable pull-out forces were observed in the experimental (2,213 N) and control groups (2,350 N; p=0.68). The mean depth of cement penetration was similar in both groups. PL during cement polymerization could decrease the operative duration by 10 min.

Conclusion: The application of PL during cement polymerization could significantly reduce operative duration and had no adverse effect on the mechanical fixation of the tibial component.

Keywords: Bone cement, pulsatile lavage, total knee arthroplasty, TKA, PMMA, polymerization

Osteoarthritis of the knee is one of the most common joint disorders in adults, and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the only causal therapy for end-stage osteoarthritis. Despite already high numbers of primary TKA procedures, a further increase is expected due to demographic development in modern industrialized countries (1). TKA is thus a highly effective routine procedure with high patient satisfaction rates and a good implant survival rate of more than 90% after 10-15 years (2).

However, despite good to excellent overall survival rates, early aseptic loosening remains one of the leading causes for revision surgery (3). In this context, there has been an increased interest in cementless TKA in recent years, particularly for younger and more active patients (4,5). However, cemented fixation is still considered the gold standard in TKA (4). Thus, optimization of the cementation technique to increase cement penetration depth is a decisive factor for primary stability (6). In this context, a cement penetration depth of 3-5 mm is known to reduce micromotion at the bone-cement interface, potentially improving implant survival (7-9).

The necessity of a thorough cementation and implantation technique stands opposed to the continuously increasing cost pressure and demand for surgical procedures of shorter durations in modern healthcare systems. Regarding TKA, pulsatile lavage (PL) should be used not only for the preparation of the bone stock prior to implantation but also for the removal of bone and cement debris following the implantation process to avoid increased wear rates (10-12). The application of PL during cement polymerization may considerably decrease the duration of surgery. However, PL may facilitate the penetration of water into the bone-cement or cement-implant interface, potentially resulting in impaired implant fixation.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of early-onset PL during bone cement polymerization on implant fixation. The following specific questions were addressed: 1) Does PL during bone cement polymerization reduce the mechanical stability of tibial components in human tibiae compared to PL after complete polymerization? 2) Does early-onset PL significantly reduce the duration of the procedure?

Materials and Methods

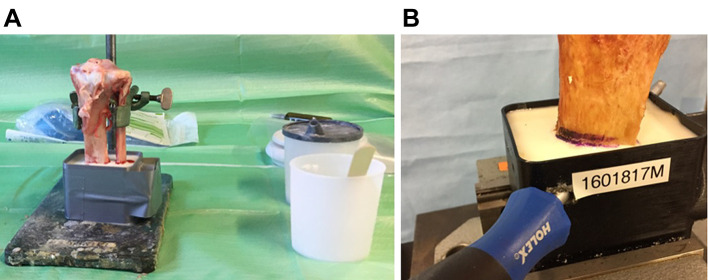

Specimen. In this experimental study, 20 commercially available freshly frozen knee joints from 10 donors were purchased from an anatomical tissue bank (MedCure, Orlando, FL, USA). Degenerative or traumatic deformities were excluded. Donor characteristics are summarised in Table I. The specimens were stored in double-plastic bags at –18˚C until usage. Before preparation, the joints were thawed overnight at a constant room temperature of 20.5˚C. The tibiae were then prepared by complete removal of the soft tissue and femoral bone. Then, the distal tibia was embedded in a synthetic resin and reinforced with a 10 mm steel bolt in a transosseous hole to allow for proper mounting in the biomechanical test setup (Figure 1). Prior to further preparation, the bone mineral density (BMD) of the trabecular bone of each specimen was analysed by quantitative computed tomography (qCT, IQon Spectral CT, Philips, Best, the Netherlands) and predefined regions of interest (ROIs) to exclude clinically relevant osteoporosis. A solid CT calibration phantom (Model 3 QCT calibration phantom Mindways, Austin, TX, USA) was used to transform calculated CT pixel values from Hounsfield units (HU) into equivalent K2HPO4 density units. A mean BMD of 95.13±0.72 mg/cm3 (88.90 to 100.50 mg/cm3) was found. The two knee joints of each donor were used as matched pairs with the random assignment of one side to group A (PL immediately after implantation) and the other side to group B (PL after complete bone cement polymerization).

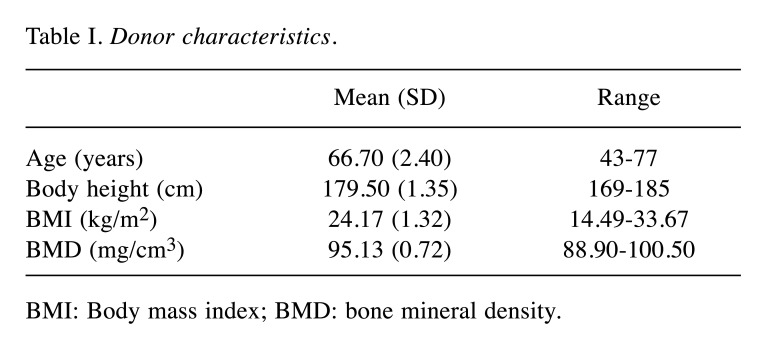

Table I. Donor characteristics.

BMI: Body mass index; BMD: bone mineral density.

Figure 1. Experimental setup of tibial specimen. (A) Tibial specimen after embedment in synthetic resin. (B) Reinforcement of the embedded tibial specimen with a steel bolt.

Surgical technique. In all cases, the tibial components of the VEGA® Total Knee System (B. Braun Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany) were used, and bone preparation was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the tibial alignment device was placed along the mechanical tibial axis. The tibial cutting block was adjusted to a tibial slope of 0˚ and a resection height of 10 mm. Following resection of the tibial joint surface, the tibial component size was determined, and keel preparation was performed. The bone bed was then further prepared with a PL device and 1000 ml of sterile saline solution to remove blood, fat and debris (Pulsavac Plus, Zimmer Biomet Deutschland GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). The bone surface was manually dried, and bone cement from a vacuum mixing system (Optipac Cement Mixing System, Zimmer Biomet Deutschland GmbH) was applied to the bone and implant surface. Prior to implantation of the tibial component, manual pressure was applied to the cement on the tibial surface, while the stem channel was left cementless (surface cementation technique). Each tibial tray was carefully inserted and impacted with ten mallet blows. A constant axial pressure of 50 N was exerted during the polymerization phase in both experimental groups to allow for optimal implant fixation. PL with 1,000 ml of saline solution at a predefined distance of 5 cm was performed immediately after implant placement in group A and after complete cement polymerization (15 min) in group B. The duration of the implantation procedure and lavage was determined for each subject in both groups. Prior to the biomechanical analysis, CT (IQon Spectral CT, Philips) was performed to analyse the penetration depth of the bone cement into the tibial cancellous bone. Metal artefacts in the CT images were reduced using a kernel filter, and the penetration depth was then measured perpendicular to the tibial surface.

Biomechanical analysis. A servo-hydraulic material testing system was used to analyse the extraction force of the tibial implants (Wolpert Universal Testing Device TZZ 707, Ludwigshafen, Germany). Therefore, a custom-made aluminium adapter plate was mounted to the central screw thread of the tibial component. A steel cardan joint and a connecting bolt were used to create a mobile connection to the force transducer. The specimens were aligned and fixed at right angles in three dimensions using two cross-line lasers (Bosch Professional Cross Line Laser GCL 2-15, Stuttgart, Germany) (Figure 2). For the pull-out test, a speed of 0.5 mm/s was applied according to previous reports (10,11). The sampling rate was 50 Hz. The maximum force before failure and the failure pattern were recorded. A force reduction of 70% was defined as the end point. Graphical analysis and sequence control of the tensile force test were performed with Test & Motion Software (Version 3.1.10) for Microsoft Windows (DOLI Elektronik GmbH, Munich, Germany).

Figure 2. Tibial specimen mounted in test system. Tibia with a custommade aluminium adapter plate mounted on the central screw thread of the tibial component in the Wolpert servo-hydraulic material testing system.

Statistical analysis. All the data collected in this study were recorded and analysed using SPSS 26 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of the data was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The pull-out force, cement penetration depth and BMD were compared using a t-test for paired samples or a Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test, depending on the data distribution. Correlations between the various study variables were assessed using the Spearman correlation.

Results

A median pull-out force of 2063 N (1250-5200 N) and 2425 N (1500-5400 N) was observed in groups A and B, respectively (Table II). No significant difference in the pull-out force was found between the two groups (p=0.19). Regarding donor characteristics, no significant correlations with the pull-out force could be identified (Table III). The tibial component size did not influence the pull-out force.

Table II. Specimen characteristics and results.

R: Right; L: left; F: female; M: male; BMD: bone mineral density.

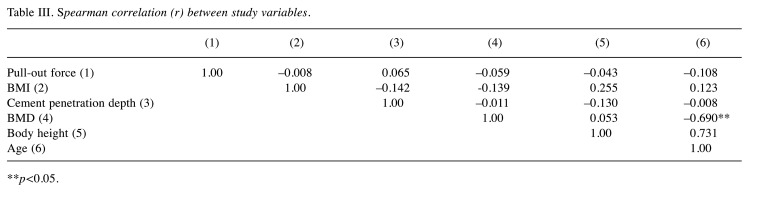

Table III. Spearman correlation (r) between study variables.

**p<0.05.

The mean depth of cement penetration was 3.97±0.20 mm in group A and 3.86±0.25 mm in group B. Again, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.096). No correlation between the cement penetration depth and donor age, body mass index, body height or BMD were identified (Table III).

Failure at the implant-cement interface was observed in 17 cases, whereas failure at the cement-bone interface was found in 3 cases. No significant difference in the BMD (p=0.16) but a highly significant difference in the cement penetration depth (3.96 mm for failure at the implant-cement interface) was observed between cases of failure at the cement-bone interface and cases of failure at the implant-cement interface (3.64 mm; p<0.001).

The mean duration of the implantation process was 4:55 min. Based on a duration of complete bone cement polymerization of 15 min in group B, PL could be applied 10:05 min earlier in group A.

Discussion

The most important finding of the present in vitro study was that PL during bone cement polymerization after the implantation of tibial prosthetic components in human tibiae did not influence implant fixation compared to PL after complete polymerization. Furthermore, by early-onset PL, the duration of the surgery could be significantly reduced by approximately 10 min. Proper implant fixation is crucial for good long-term results after TKA since aseptic loosening is still one of the main reasons for revision surgery despite improvements in materials and surgical techniques (13). According to the Australian joint registry (AOANJRR Annual Report 2018), higher revision rates due to early aseptic loosening were identified for cementless fixation (14). Micromotion at the implant-bone interface leading to insufficient osseous integration is assumed to be causative in this regard. Consequently, cemented fixation in primary TKA can still be considered the gold standard.

PL is commonly used during TKA, mainly prior to component implantation, to remove blood, fat and debris from the trabecular bone surface (15). In this context, Schlegel et al. (10) demonstrated significantly improved cement penetration into the tibial cancellous bone after PL than after syringe lavage. In contrast to their results, a cement penetration depth of 3.97±0.20 mm in group A and 3.86±0.25 mm in group B was identified in the present study. These values are more than twice as high as those published by Schlegel et al. (10), despite a similar study setup. One potential reason may be differences in the measurement method, as they used an automatic segmentation algorithm and calculated the penetration depth for the entire cemented area. Furthermore, different bone cements were used in both studies, possibly explaining these results. Generally, an interdigitation depth of at least 2-3 mm has been recommended to allow for engagement of the cement with at least one layer of transverse trabeculae and in turn achieve proper resistance to shear and tensile forces (16). Supporting the results of the present study, other studies using modern cementation techniques have suggested a penetration depth of at least 3-5 mm (8,9). Despite manual application of the cement in the present study without a pressurization technique, a proper penetration depth was achieved, confirming previous results reported by Kopec et al. (17). They identified only minor improvement in the cement interdigitation depth in their study when using cement pressurization.

However, it is also of great importance that all debris be removed by PL after the implantation process. Despite previous studies suggesting that particles resulting from the decomposition of biomaterials typically have a size on the submicron scale (18), Niki et al. (19) showed that the diameter of intraoperatively produced particles could be as large as 240 μm for bone and 340 μm for polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). Particles of this size can significantly influence the wear rate and thus implant survival in the long run. The application of high-pressure PL during the process of bone cement polymerization may, however, carry a risk of water penetration into the implant-cement or cement-bone interface, potentially resulting in impaired implant fixation. On the other hand, syringe lavage may not be as effective as PL, and PL after the completion of polymerization may significantly extend operative duration. In the present study, we identified similar pull-out forces in both study groups, suggesting that implant fixation was not impeded by PL during cement polymerization. Similar to the penetration depth, the pull-out forces in the present study were approximately twice as high as those published by Schlegel et al. (10). This could be at least partially explained by the greater cement penetration depth in the present study. However, failure was found to occur at the implant-cement interface in all PL cases in their study and in 17 of 20 cases in the present study, suggesting a certain influence of the implants used in either study. In contrast to this hypothesis, however, Schlegel et al. (11) reported significantly higher pull-out forces and failure at the bone-cement interface in most cases in a later study with a similar experimental setup.

In the present study, a substantial time saving of 10 min due to PL during the cement polymerization process was demonstrated. From an economic point of view, this reduction in cost-intensive operation time offers considerable potential for financial savings in an increasingly competitive healthcare environment. From a clinical perspective, a shorter operative duration for TKA can significantly decrease the risk of intraoperative bacterial contamination, as confirmed by a recent study by Hanada et al. (20). Shorter durations of surgery and anaesthesia are additionally associated with reductions in blood loss and the risk of peri- and postoperative complications (21). This allows for rapid recovery, particularly in high-risk and geriatric patients.

However, several limitations of the present study must be noted. First, this in vitro study was performed under laboratory conditions and could thus not completely reflect intraoperative conditions during a TKA procedure, such as blood residues on the bone surface. Second, the axial pull-out force was a simplification used to analyse the primary fixation of the tibial tray. However, this is a non-physiological loading situation; in vivo, the joint is exposed to dynamic axial compression and shear forces. Thus, the present results can only be cautiously transferred to in vivo conditions. Third, the relatively small sample size in this study may restrict the generalizability of the present results.

In conclusion, the use of PL in TKA should be considered as the gold standard, not only for the preparation of the bone bed before the implantation but also for the removal of debris after the implantation process in order to avoid increased wear rates. The application of PL during cement polymerization had no adverse effect on the mechanical fixation of the tibial component and could significantly reduce the operative duration.

Conflicts of Interest

All Authors declare that they have no competing interests regarding this study.

Authors’ Contributions

Claudio Glowalla: Data analysis, preparation of manuscript; Max Ertl: Data acquisition, data analysis; Ulrich Lenze: Data analysis, preparation of manuscript; Igor Lazic: Data acquisition, data analysis, preparation of manuscript; Rainer Burgkart: Study design, approval of manuscript; Jan J. Lang: Experimental design, data acquisition; Rüdiger von Eisenhart-Rothe: Study design, approval of manuscript; Florian Pohlig: Study design, data analysis, approval of manuscript.

References

- 1.Schwartz AM, Farley KX, Guild GN, Bradbury TL Jr. Projections and epidemiology of revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States to 2030. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(6S):S79–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papas PV, Congiusta D, Cushner FD. Cementless versus cemented fixation in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2019;32(7):596–599. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1678687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(404):7–13. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller AJ, Stimac JD, Smith LS, Feher AW, Yakkanti MR, Malkani AL. Results of cemented vs cementless primary total knee arthroplasty using the same implant design. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nam D, Lawrie CM, Salih R, Nahhas CR, Barrack RL, Nunley RM. Cemented versus cementless total knee arthroplasty of the same modern design: a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(13):1185–1192. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.01162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller MA, Terbush MJ, Goodheart JR, Izant TH, Mann KA. Increased initial cement-bone interlock correlates with reduced total knee arthroplasty micro-motion following in vivo service. J Biomech. 2014;47(10):2460–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bert JM, McShane M. Is it necessary to cement the tibial stem in cemented total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(356):73–78. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanlommel J, Luyckx JP, Labey L, Innocenti B, De Corte R, Bellemans J. Cementing the tibial component in total knee arthroplasty: which technique is the best. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(3):492–496. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutz MJ, Pincus PF, Whitehouse SL, Halliday BR. The effect of cement gun and cement syringe use on the tibial cement mantle in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(3):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlegel UJ, Siewe J, Delank KS, Eysel P, Püschel K, Morlock MM, de Uhlenbrock AG. Pulsed lavage improves fixation strength of cemented tibial components. Int Orthop. 2011;35(8):1165–1169. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1137-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlegel UJ, Püschel K, Morlock MM, Nagel K. An in vitro comparison of tibial tray cementation using gun pressurization or pulsed lavage. Int Orthop. 2014;38(5):967–971. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2303-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalteis T, Pförringer D, Herold T, Handel M, Renkawitz T, Plitz W. An experimental comparison of different devices for pulsatile high-pressure lavage and their relevance to cement intrusion into cancellous bone. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(10):873–877. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delanois RE, Mistry JB, Gwam CU, Mohamed NS, Choksi US, Mont MA. Current epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9):2663–2668. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Government Department of Health - Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR): Hip, knee & shoulder arthroplasty: 2018 annual report. National Joint Replacement Registry, 2018. Available at: https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/documents/10180/576950/Hip%2C%20Knee%20%26%20Shoulder%20Arthroplasty. [Last accessed on February 3, 2022]

- 15.Lutz MJ, Halliday BR. Survey of current cementing techniques in total knee replacement. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72(6):437–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2002.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker PS, Soudry M, Ewald FC, McVickar H. Control of cement penetration in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;(185):155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kopec M, Milbrandt JC, Duellman T, Mangan D, Allan DG. Effect of hand packing versus cement gun pressurization on cement mantle in total knee arthroplasty. Can J Surg. 2009;52(6):490–494. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horowitz SM, Doty SB, Lane JM, Burstein AH. Studies of the mechanism by which the mechanical failure of polymethylmethacrylate leads to bone resorption. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(6):802–813. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, Tomatsu T, Toyama Y. How much sterile saline should be used for efficient lavage during total knee arthroplasty? Effects of pulse lavage irrigation on removal of bone and cement debris. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(1):95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanada M, Hotta K, Furuhashi H, Matsuyama Y. Intraoperative bacterial contamination in total hip and knee arthroplasty is associated with operative duration and peeling of the iodine-containing drape from skin. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2020;30(5):917–921. doi: 10.1007/s00590-020-02653-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravi B, Jenkinson R, O’Heireamhoin S, Austin PC, Aktar S, Leroux TS, Paterson M, Redelmeier DA. Surgical duration is associated with an increased risk of periprosthetic infection following total knee arthroplasty: A population-based retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;16:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]