Abstract

Objective:

Transoral surgery (TOS) for oropharyngeal carcinoma (OPC) is steadily becoming more routine. Expected post-treatment swallow function is a critical consideration for preoperative counseling. The objective of this study was to identify predictors of swallow dysfunction following TOS for advanced T-stage (T3-T4) OPC.

Methods:

A retrospective review from 1997 to 2016 at a single institution was performed. Eighty-two patients who underwent primary transoral resection of locally advanced OPCs with at least 1 year of postoperative follow-up were included.

The primary outcome measure was swallow function, as measured by the Functional Outcomes Swallowing Scale (FOSS) at 1 year postoperatively. Operative reports were reviewed, and the extent of resection and type of reconstruction were documented. Conjunctive consolidation was then performed to incorporate multiple variables and their impact on swallow function into a clinically meaningful classification system.

Results:

Fifty-six patients (68%) had acceptable swallowing at 1 year. T4 tumor stage and receipt of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy (CRT) were strongly associated with poor swallowing but did not reach statistical significance. Only base of tongue (BOT) resection ≥50% (OR 3.19, 95%CI 1.21–8.43) and older age (OR 1.06, 95%CI 1.00–1.12) were significantly associated. Utilizing T-stage, adjuvant CRT, and BOT resection, a conjunctive consolidation was performed to develop a classification system for swallow dysfunction at 1 year.

Conclusion:

This study provides risk stratification for swallow function at 1 year following primary transoral resection of locally advanced OPCs. BOT resection ≥50%, especially when coupled with T4 tumor stage or adjuvant CRT, was associated with poor long-term swallow outcomes.

Keywords: transoral surgery, swallow function, oropharynx cancer

Introduction

Transoral surgery (TOS) for resection of oropharyngeal carcinoma (OPC) presents a minimally invasive surgical approach to an often difficult to reach area. Compared with standard transcervical approaches to the oropharynx, TOS is an attractive option for select patients, with the potential to decrease surgical morbidity while maintaining oncologic outcomes.1 TOS encompasses transoral laser microsurgery (TLM), transoral robotic surgery (TORS) which is steadily becoming more widely accepted and routine, and loupe magnification with monopolar cautery.

The current standard of care therapeutic options for advanced OPC are definitive chemoradiation therapy (CRT) or primary surgery with adjuvant radiation or chemoradiation. Pre-treatment counseling is a critical step in helping patients decide which treatment modality to pursue. Aside from the requisite discussion on oncologic outcomes, post-treatment swallow function is a significant factor to consider. Definitive CRT has already been shown to cause up to 40% of patients to experience significant dysphagia within 3 years.2 In contrast, multiple studies have shown much lower rates of swallow dysfunction in patients after TOS, with chronic gastrostomy tube rates <10%.3–5 Similar studies also note that extensive base of tongue (BOT) and soft palate (SP) resection or cranial nerve (hypoglossal, vagus) transection can lead to worse swallow function.6–9 Increased extent of cervical lymphadenectomy has also been correlated with swallow dysfunction.10 However, most surgical reports do not include transorally resected advanced tumors (T)-stage T3-T4, nor delineate the association between the extent of the defect and the impact of reconstruction on swallow function. The objective of this study is to identify predictors of swallow function at 1 year following transoral resection of locally advanced OPC.

Materials and Methods

Setting and Subjects

All data collection and analyses were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine. A retrospective review was performed of patients undergoing primary transoral resection of locally advanced (pathologic T3-T4) OPC at a single academic institution between 1997 and 2016. T3 and T4 tumor stages were determined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition guidelines.11 Pathologic rather than clinical T-stage was utilized due to its closer correlation with post-surgical defect size. Primary transoral resection included TORS, TLM, or loupe magnification under direct visualization and encompassed a previously published cohort whose swallowing outcomes were investigated.12,13 Patients ≥ 18 years-old who underwent definitive surgical transoral treatment (+/− hybrid lateral pharyngotomy if complete tumor extirpation was limited by transoral access)14 and were disease-free at 1 year postoperatively were included in the study. Criteria for exclusion were: prior diagnosis or treatment of head and neck cancer, primary nonsurgical treatment, histologic diagnosis other than squamous cell carcinoma, recurrence within 1 year of surgery, and tumor resection requiring conversion to an open transcervical mandibulotomy.

Data Collection

Collected data included demographics, comorbidities as measured by the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 (ACE-27) score, tumor presentation and pathology, surgical details, adjuvant therapy, recurrences, and postoperative tracheostomy dependence.15 Each patient’s primary operative report was carefully reviewed by physicians (JG, MT, JR) familiar with transoral surgical anatomy who were blinded to swallow outcomes. The extent of resection of each oropharyngeal subsite (SP, lateral pharynx/tonsil, and BOT) was documented and graded by percent of resection. Extirpation of critical neurovascular, muscular, or cartilaginous structures was documented. Creation of a pharyngotomy or an exposed carotid artery, concurrently performed neck dissection, as well as detailed descriptions of the reconstructive maneuvers (local, regional or free flap) were also recorded. Pathology reports were reviewed for pathologic TNM staging, tumor histology, and p16 status.

Receipt of adjuvant therapy (radiation and/or chemotherapy) and the dosage and location of the radiation field (primary site and/or neck irradiation) were collected. Clinic notes were reviewed for timing of recurrent locoregional or distant disease or death. Pre- and postoperative gastrostomy tube use as well as presence of long-term postoperative tracheostomy (>1 year) were recorded.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was swallow function at 1 year postoperatively, as measured by the Functional Outcome Swallowing Scale (FOSS)16 (Table 1). The FOSS scale incorporates subjective and objective factors to create a nominal classification of swallow function from 0 to 5. Zero represents normal function without any symptoms, and 5 represents complete dependence on nonoral feeding. Patients with a FOSS score 0–2 had compensated swallow function with only episodic symptoms of dysphagia and were classified with acceptable function. Patients with a FOSS score 3–5 had decompensated swallow function with weight loss, recurrent aspiration, or nonoral feeding and were classified with poor function. Two physicians (JG, MT) reviewed speech pathology evaluations, gastrostomy tube status, and physician follow-up notes to determine FOSS scores by consensus. The division into “acceptable” and “poor” FOSS score subsets was adopted from a previously published study.13

Table 1.

Functional Outcome Swallowing Scale (FOSS)16

| Stage | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 0 | Normal function and asymptomatic. |

| 1 | Normal function with episodic or daily symptoms of dysphagia. |

| 2 | Compensated abnormal function manifested by considerable dietary modifications or prolonged mealtime (without weight loss or aspiration). |

| 3 | Decompensated abnormal function with weight loss of 10% of body weigh over 6 months owing to dysphagia; or daily cough, gagging, or aspiration during meals. |

| 4 | Severely decompensated abnormal function with weight loss of 10% of body weight over 6 months owing to dysphagia; or severe aspiration with bronchopulmonary complications. Nonoral feeding for most nutrition. |

| 5 | Nonoral feeding for all nutrition. |

(Adapted version provided by Rich, et al.13)

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute). Basic descriptive statistics were used to define patient characteristics. Logistic regression analysis was utilized to detect any associated differences between the acceptable and poor swallow function groups.

Conjunctive consolidation was performed to incorporate multiple variables and stratify data into a clinically meaningful classification system.17 This statistical technique created a classification predictive of poor post-treatment swallow function. Odds ratios from a logistic regression model were used to assess strength of association between the novel classification system and outcomes after controlling for other potential risk factors. The concordance statistic (c-statistic) was calculated, which determines the probability that a random patient will experience the event in question and is used to assess discrimination of the novel staging system. A value < 0.5 reflects a poor model, and a value of 1 indicates a perfect fit.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A total of 112 cases of advanced stage OPC undergoing TOS were evaluated, and 82 patients met eligibility criteria and were included in the study. Pathologic tumor stage was T3 in 45 patients (55%), and T4 in 37 patients (45%). Eight patients (10%) had no BOT resection, 45 patients (55%) had BOT resection >0% and <50%, and 29 patients (35%) had ≥50% BOT resection. Six patients (8%) received no adjuvant therapy, 31 (39%) received adjuvant radiation therapy only, and 42 (53%) received combined adjuvant CRT. Adjuvant therapy status for 3 patients was unknown. The radiation fields could not be determined in most patients.

At 1 year postoperatively, swallow function was acceptable (FOSS 0–2) in 56 patients (68%), and poor (FOSS 3–5) in 26 patients (32%). Thirteen patients, or one half of those with poor swallow function, were gastrostomy tube dependent. Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and swallow outcomes.

| All n(%) | Acceptable Swallowing n(%) | Poor Swallowing n(%) | OR Ɨ | 95% CIǂ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 59.4 (9.2) | 58.0 (9.2) | 62.5 (8.3) | 1.06 | 1.00–1.12 |

|

| |||||

| Age (dichotomous) | |||||

| Less than 60 | 45 (55) | 34 (61) | 11 (42) | ||

| 60 or Greater | 37 (45) | 22 (39) | 15 (58) | 2.11 | 0.82–5.42 |

|

| |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 74 (90) | 50 (89) | 24 (92) | ||

| Female | 8 (10) | 6 (11) | 2 (8) | 0.69 | 0.13–3.70 |

|

| |||||

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 31 (38) | 23 (41) | 8 (30) | ||

| Past | 33 (40) | 24 (43) | 9 (35) | 1.08 | 0.36–3.27 |

| Current | 18 (22) | 9 (16) | 9 (35) | 2.88 | 0.84–9.79 |

|

| |||||

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 31 (38) | 23 (41) | 8 (31) | ||

| Past or Current Smoker | 51 (62) | 33 (59) | 18 (69) | 1.57 | 0.58–4.21 |

|

| |||||

| ACE | |||||

| 0 (None) | 33 (40) | 24 (43) | 9 (35) | ||

| 1 (Mild) | 40 (49) | 26 (46) | 14 (54) | 1.44 | 0.53–3.92 |

| 2 (Moderate) | 7 (9) | 4 (7) | 3 (11) | 2.00 | 0.37–10.75 |

| 3 (Severe) | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

|

| |||||

| ACE | |||||

| None | 33 (40) | 24 (43) | 9 (35) | ||

| Comorbidities Present | 49 (60) | 32 (57) | 17 (65) | 1.42 | 0.54–3.72 |

|

| |||||

| Site (Consolidated) | |||||

| BOT | 42 (51) | 26 (46) | 16 (62) | ||

| Tonsil | 40 (49) | 30 (54) | 10 (38) | 0.54 | 0.21–1.40 |

|

| |||||

| Tumor Histology | |||||

| Well-differentiated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 9 (11) | 4 (7) | 5 (20) | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 16 (20) | 10 (19) | 6 (24) | 0.48 | 0.09–2.52 |

| Non-keratinizing | 48 (61) | 36 (67) | 12 (48) | 0.27 | 0.06–1.16 |

| Other | 6 (8) | 4 (7) | 2 (8) | 0.40 | 0.05–3.42 |

| Missing | 3 | ||||

|

| |||||

| pT Pathologic Tumor Stage (AJCC 7th ed.) | |||||

| T3 | 45 (55) | 35 (63) | 10 (38) | ||

| T4a, T4b | 37 (45) | 21 (37) | 16 (62) | 2.67 | 1.02–6.95 |

|

| |||||

| pN Pathologic Nodal Stage (AJCC 7th ed.) | |||||

| N0 | 12 (15) | 11 (20) | 1 (4) | ||

| N1 | 7 (9) | 5 (9) | 2 (8) | 4.40 | 0.32–60.61 |

| N2a | 9 (11) | 8 (14) | 1 (4) | 1.38 | 0.07–25.43 |

| N2b | 30 (37) | 21 (37) | 9 (36) | 4.71 | 0.53–42.17 |

| N2c | 21 (26) | 9 (16) | 12 (48) | 14.67 | 1.59–135.32 |

| N3 | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Missing | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||

| pStage Pathologic Stage (AJCC 7th ed.) | |||||

| I, II, III | 9 (11) | 8 (15) | 1 (4) | ||

| IVA, IVB | 71 (89) | 46 (85) | 25 (96) | 4.35 | 0.51–36.78 |

| Missing | 2 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Type of Surgical Treatment | |||||

| TLM | 74 (90) | 48 (86) | 26 (100) | ||

| TORS | 4 (5) | 4 (7) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Loupes | 4 (5) | 4 (7) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

|

| |||||

| BOT Resection | |||||

| 0–49% Resection | 53 (65) | 41 (73) | 12 (46) | ||

| ≥50% Resection | 29 (35) | 15 (27) | 14 (54) | 3.19 | 1.21–8.43 |

|

| |||||

| Lateral Pharynx/Tonsil Resection | |||||

| None to Parapharyngeal Fat Exposure | 73 (89) | 49 (88) | 24 (92) | ||

| Exposed Carotid | 9 (11) | 7 (12) | 2 (8) | 0.58 | 0.11–3.02 |

|

| |||||

| Soft Palate Resection | |||||

| 0–49% Resection | 77 (94) | 53 (95) | 24 (92) | ||

| ≥50% Resection | 5 (6) | 3 (5) | 2 (8) | NA | NA |

|

| |||||

| Neck Dissection | |||||

| None | 4 (5) | 3 (6) | 1 (4) | ||

| Ipsilateral | 40 (49) | 31 (55) | 9 (35) | 0.87 | 0.08–9.43 |

| Bilateral | 38 (46) | 22 (39) | 16 (61) | 2.18 | 0.21–22.95 |

|

| |||||

| Neck Dissection | |||||

| None or Ipsilateral | 44 (54) | 34 (61) | 10 (38) | ||

| Bilateral | 38 (46) | 22 (39) | 16 (62) | 2.47 | 0.95–6.43 |

|

| |||||

| CNX Resection | |||||

| None | 81 (99) | 56 (100) | 25 (96) | ||

| Performed | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | NA | NA |

|

| |||||

| CNXII Resection | |||||

| None | 73 (89) | 51 (91) | 22 (85) | ||

| Performed | 9 (11) | 5 (9) | 4 (15) | NA | NA |

|

| |||||

| Lingual Nerve Resection | |||||

| None | 71 (87) | 49 (88) | 22 (85) | ||

| Performed | 11 (13) | 7 (12) | 4 (15) | 1.27 | 0.34–4.80 |

|

| |||||

| Pterygoid Resection | |||||

| None | 68 (83) | 44 (79) | 24 (92) | ||

| Performed | 14 (17) | 12 (21) | 2 (8) | 0.31 | 0.06–1.48 |

|

| |||||

| Type of Reconstruction | |||||

| None, Local Flap, or Other | 75 (92) | 52 (93) | 23 (89) | ||

| Regional or Free Flap | 7 (8) | 4 (7) | 3 (11) | NA | NA |

|

| |||||

| Pharyngotomy | |||||

| None | 47 (57) | 34 (61) | 13 (50) | ||

| Performed | 35 (43) | 22 (39) | 13 (50) | 1.55 | 0.61–3.95 |

|

| |||||

| p16 | |||||

| Negative | 5 (6) | 4 (7) | 1 (4) | ||

| Positive | 74 (94) | 51 (93) | 23 (96) | 1.80 | 0.19–17.05 |

| Missing | 3 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Adjuvant Therapy | |||||

| None or Radiation Only | 37 (47) | 29 (54) | 8 (32) | ||

| Chemoradiation Therapy | 42 (53) | 25 (46) | 17 (68) | 2.47 | 0.91–6.68 |

| Missing | 3 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Recurrence (Any) | |||||

| None | 60 (73) | 43 (77) | 17 (65) | ||

| Present | 22 (27) | 13 (23) | 9 (35) | 1.75 | 0.63–4.85 |

|

| |||||

| Recurrence (Local or Regional) | |||||

| None or Distant | 71 (87) | 48 (86) | 23 (89) | ||

| Local or Regional | 11 (13) | 8 (14) | 3 (11) | 0.78 | 0.19–3.23 |

|

| |||||

| Long-term Tracheostomy, 1 year follow-up | |||||

| No | 77 (94) | 55 (98) | 22 (85) | ||

| Yes | 5 (6) | 1 (2) | 4 (15) | 10.00 | 1.06–94.54 |

|

| |||||

| Trismus, 1 year follow-up | |||||

| No | 65 (79) | 46 (82) | 19 (73) | ||

| Yes | 17 (21) | 10 (18) | 7 (27) | 1.70 | 0.56–5.11 |

OR = Odds Ratio

CI = Confidence Interval

Logistic Regression

Patients with a T4 tumor stage had significantly greater risk of poor swallow function when compared to T3 (OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.02–6.95). Fifty percent or greater BOT resection compared with <50% resection was also significantly associated with poor swallow function (OR 3.19, 95% CI 1.21–8.43). Older age had a small but statistically significant effect (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00–1.12). Patients who received adjuvant CRT tended to have greater risk of swallow dysfunction compared to those who received adjuvant radiation only or no adjuvant therapy, although this effect was not statistically significant (OR 2.47, 95% CI 0.91–6.68). Extent of resection of lateral pharynx/tonsil, medial pterygoid resection, extent of neck dissection, and pharyngotomy did not statistically impact swallow outcomes. The following variables had too few numbers and were not analyzed: type of reconstruction, extent of SP resection, and vagus and hypoglossal nerve transection.

Conjunctive Consolidation

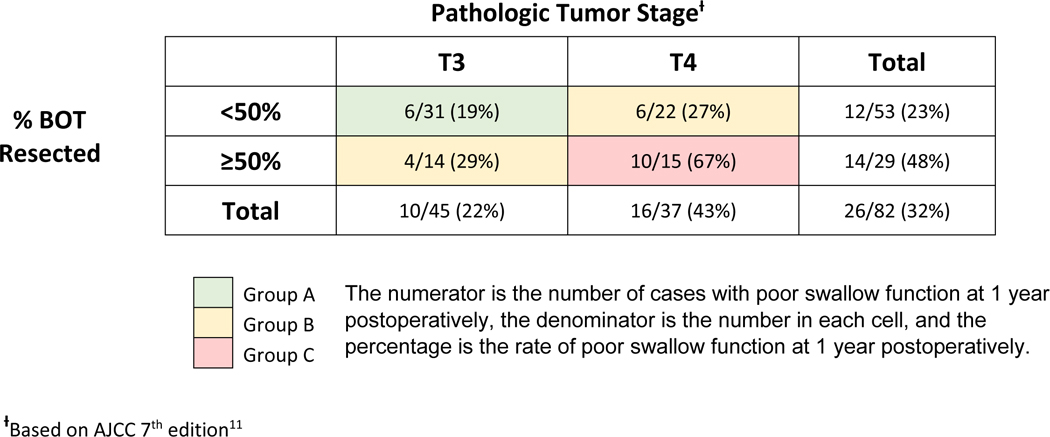

Due to the small number of patients, only three variables could be utilized in conjunctive consolidation analysis without risk of overfitting the model. The variables with the highest clinical significance and strongest statistical association were chosen for analysis and included: BOT resection ≥50%, T-stage, and receipt of adjuvant CRT. Utilizing these three factors, a conjunctive consolidation was performed to show their composite effects on swallow dysfunction at 1 year and stratify the outcomes. First, extent of BOT resection and T-stage were conjoined to create a three-category staging system with Groups A, B, and C (Table 3). Patients with T3 tumors and BOT resection <50% had the lowest rate of swallow dysfunction (6 of 31, 19%) and formed Group A. Patients with T3 tumors and BOT resection ≥50% or T4 tumors and BOT resection <50% comprised Group B and had intermediate risk of swallow dysfunction (10 of 36, 28%). The highest rate of swallow dysfunction (10 of 15, 67%) formed Group C and was comprised of patients with T4 tumors and ≥50% BOT resection. The new classification incorporating BOT resection and T-stage information had good discriminative power, with a c-statistic of 0.68.

Table 3.

Rates of poor swallow function at 1 year postoperatively in conjunction with base of tongue (BOT) resection and pathologic tumor stage.

|

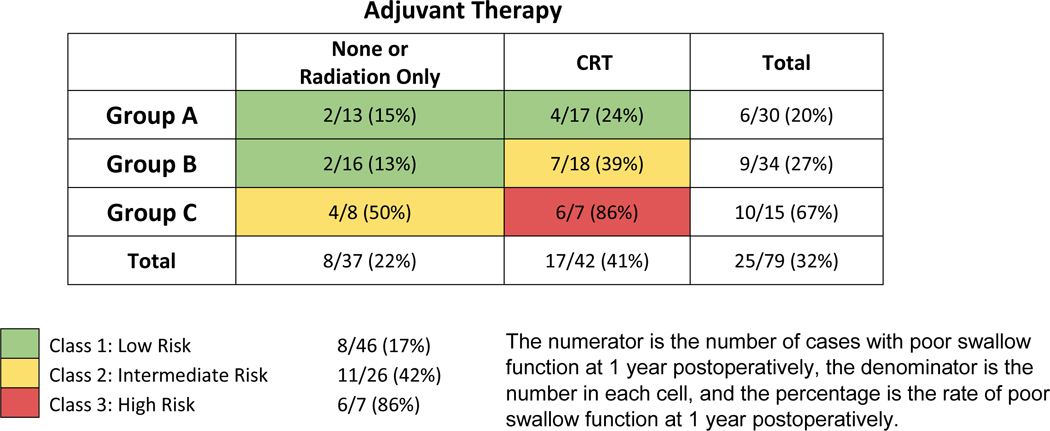

The third variable (adjuvant CRT) was then conjoined with the new Group ABC consolidation to create the final combined classification system for predicting swallow dysfunction at 1 year (Table 4). Patients in Group A or Group B with no adjuvant CRT, or those in Group A with adjuvant CRT defined Class I and had the lowest rate of swallow dysfunction (8 of 46, 17%). Patients in Group B with adjuvant CRT or Group C with no adjuvant CRT comprised Class II and had intermediate rates of swallow dysfunction (11 of 26, 42%). The highest rate of swallow dysfunction (6 of 7, 86%) formed Class III and was comprised of patients in Group C with adjuvant CRT. Thus, the final classification system demonstrated rates of swallow dysfunction as follows: Class I - 17%, Class II - 42%, and Class III - 86%. The c-statistic for the new classification system was 0.72.

Table 4.

Rates of poor swallow function at 1 year postoperatively in conjunction with BOT resection, pathologic tumor stage, and adjuvant chemoradiation therapy (CRT).

|

Discussion

Traditionally, surgical approaches to advanced oropharynx tumors require a mandibulotomy or large transcervical pharyngotomy. These techniques often require reconstruction and tracheotomy and have high functional morbidity due to disruption of musculoskeletal structures responsible for the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing. TOS has the potential to decrease surgical morbidity while maintaining oncologic outcomes.1

This study demonstrated that patients undergoing primary transoral resection of locally advanced OPC had varying levels of swallow dysfunction, predicted by the amount of BOT resection, pathologic T-stage, and receipt of adjuvant CRT. Yet, most patients (56 patients, 68%) had acceptable swallow outcomes at 1 year postoperatively. Of the 26 patients (32%) with poor swallow outcomes, one half (13 patients, 16%) were gastrostomy tube dependent, which is within the wide range of what is reported in the literature for T3-T4 OPC (9 to 36%).3,18,19

In bivariate analysis, patients with pathologic T-stage 4 were more likely to have poor swallow function than those with T-stage 3 (OR 2.67). This finding is clinically intuitive, and previous studies have shown similar outcomes with increasing T-stage.13,19 For example, Dziegielewski et al. published a 27 times increased risk of requiring gastrostomy tube feedings in T4 versus T3 OPC removed via TORS.3

In this study, patients with ≥50% BOT resection were over 3 times more likely to have poor swallow function (OR 3.19). Extent of resection of SP or lateral pharynx/tonsil was not significantly impactful. The BOT is critical to the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, contributing to bolus propulsion and airway protection through epiglottic tilt.20 As a result, it is reasonable to expect extensive BOT resection or CRT to lead to worse swallow outcomes, and multiple studies support this notion. Pauloski et al. examined 144 patients after primary surgery +/− adjuvant therapy for oral cavity cancer or OPC.6 Oropharyngeal swallow efficiency (OPSE) was negatively correlated with the percent of tongue base resected. In a retrospective review of advanced stage OPC treated with definitive CRT, Shiley et al. found a significantly higher rate of gastrostomy tube dependence in patients with BOT versus tonsil tumors (67% vs 25%).21

The patients in the current study all had advanced stage disease and were therefore recommended to undergo at least adjuvant radiation. It is well-established that any increase in radiation dosage may significantly worsen swallow function via post-radiation fibrosis of swallowing organs, specifically the pharyngeal constrictors and the glottic and supraglottic larynx.22–26 The dose-dependent increase in potential side effects (i.e. mucositis, fibrosis, stricture) is an important point for pretreatment counseling, as the risk is considerably higher with definitive versus adjuvant radiation doses.

Forty-two patients (53%) in the study underwent additional concurrent adjuvant chemotherapy due to the presence of positive margins or extranodal extension. These patients had a 2.5 times greater risk of swallow dysfunction when compared to those who received radiation only or no adjuvant therapy, although it was not statistically significant (OR 2.47, 95% CI 0.91–6.68). The synergistic impact on swallow dysfunction from CRT is well-supported in the literature. A Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) analysis by Francis et al. demonstrated a 2.7 odds ratio of dysphagia among patients receiving definitive CRT versus those undergoing surgery alone, compared with a 2.0 odds ratio among those undergoing surgery with adjuvant radiation versus surgery alone.2 More et al. performed a prospective study comparing swallow function of patients with advanced stage oropharynx and supraglottis cancers treated with TORS and adjuvant therapy versus primary CRT.27 Long term swallow-related quality of life, as measured by the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI), was almost two times higher in patients with T3 tumors treated with TORS and adjuvant therapy versus primary CRT. Additionally, 60% of those patients undergoing TORS had adjuvant CRT, and they still reported better swallow scores. The above considerations underscore the critical importance of ongoing de-escalation studies in HPV-mediated OPC in which radiotherapy dose/treatment volume and the use of adjuvant CRT are under investigation.28

Overall, only 17 patients (21%) underwent a local flap, and 7 patients (9%) underwent a regional or free flap reconstruction. Due to the low number of patients undergoing flap reconstruction, no conclusions could be made regarding the impact of reconstructive efforts on swallow function. Of note, 22 out of 29 (76%) of those patients with ≥50% BOT resection did not have any type of reconstruction. Though the data is sparse, other studies have shown variable swallow function with flap reconstruction for defects involving ≥50% BOT resection. Rieger et al. followed a group of 32 patients with OPC requiring >50% BOT resection followed by radial forearm free flap (RFFF) reconstruction.29 At 1 year postoperatively, they showed good swallow outcomes, with only 14% (3/21) of patients requiring use of a gastrostomy tube. Seikaly et al. prospectively evaluated swallow function after RFFF reconstruction as well. Out of 9 patients with T3-T4 disease and ≥50% BOT resection, 3 (33%) had aspiration or required a gastrostomy tube.30 In a cross-sectional study by Winter et al., 5/9 (56%) T3-T4 OPC patients with BOT free flap reconstruction reported poor swallow-related quality of life.31 In our study, 14/29 patients (48%) with ≥50% BOT resection had poor swallow function, which is on the higher end of published data. This data may be due to a lower number of flap reconstructions in our population.

Interestingly, there were multiple factors that were not statistically significant in bivariate analysis that intuitively would be thought to impact swallow function, namely extent of lateral pharynx/tonsil resection, resection of pterygoid musculature, tracheostomy dependence, extent of neck dissection, and limited pharyngotomy. The frequency of SP and cranial nerve (hypoglossal, vagus) resection was too low to make inferences on the impact on swallow function.

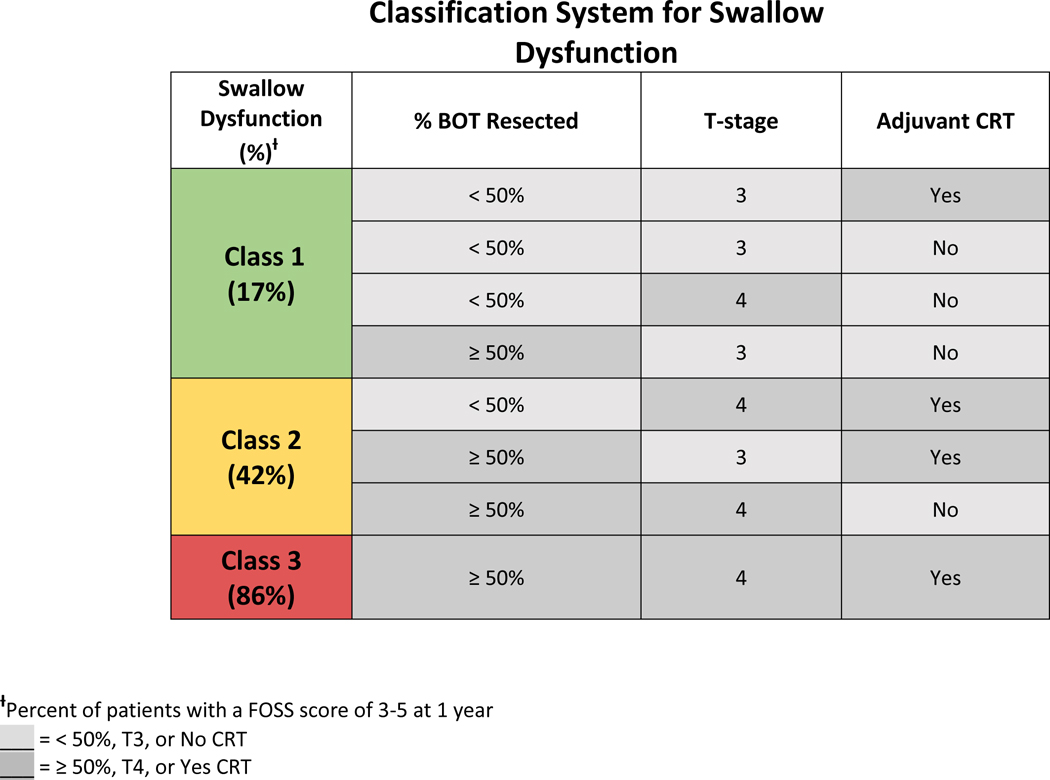

This paper presents a novel classification system that consolidates three predictive factors of poor swallow function that have also been supported by previously published data. Namely tumor stage, extent of BOT resection, and adjuvant CRT are combined to stratify patients into low, intermediate, or high risk of post-treatment swallow dysfunction. The low risk group included: patients with T3 tumors and <50% BOT resection, T3 tumors and ≥50% BOT resection without adjuvant CRT, or T4 tumors and <50% BOT resection without adjuvant CRT. The intermediate risk group included: patients with T3 tumors and ≥50% BOT resection with adjuvant CRT, T4 tumors and <50% BOT resection with adjuvant CRT, or T4 tumors and ≥50% BOT resection without adjuvant CRT. The high-risk group included: patients with T4 tumors and ≥50% BOT resection with adjuvant CRT (Table 5).

Table 5.

Classification system that stratifies swallow dysfunction at 1 year postoperatively into low, intermediate, and high risk.

|

This study has limitations, however, that should be considered. Due to the retrospective nature, there were occasional incomplete data regarding intraoperative findings and swallow function. Regarding swallow function evaluation, objective studies (i.e. modified barium swallow) or patient-reported outcome instruments (i.e. MDADI) were not consistently performed in this population, so the validated FOSS instrument was utilized. Due to cancer recurrence in this high-risk population as well as incomplete data, we were unable to analyze or comment on swallow function past 1 year. This limitation may have impacted our swallow outcomes, as swallow function following OPC treatment is dynamic and can change over time.13 Another potential limitation is that the majority of surgeries were performed by a single surgeon (61/82, 74%). As such, the data may be more internally consistent but less generalizable to other surgeons or institutions. Multiple variables also occurred with a frequency too low to make inferences on their impact on swallow function. Future studies with larger datasets should be conducted to establish this relationship.

Oncologic outcomes from surgical versus nonsurgical modalities for advanced OPC are controversial.32–34 Survival rates are even further confounded by the increased prevalence of human papilloma virus (HPV) positivity, which is known to impart improved survival outcomes.35 Due to the often unclear oncologic outcomes of surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for locally advanced OPC, treatment may ultimately be determined by surgeon or patient preference, and/or perceived quality of life factors (i.e. swallow function). Poor swallow function can be a devastating consequence of treatment for OPC and has been shown to lead to social isolation, decreased quality of life, and an overall decrease in emotional well-being.36–38 It is critical that swallow function be an important part of any discussion regarding treatment of tumors of the oropharynx. This study provides expected risk of swallow dysfunction after primary transoral resection of advanced stage OPC, data that may ultimately help patients decide between treatment modalities.

Conclusion

This study provides predictors of swallow function at 1 year after treatment for advanced T3 and T4 OPCs removed by TOS. We observed acceptable swallowing in the majority of patients. However, BOT resection ≥50%, especially when coupled with T4 tumor stage or adjuvant CRT, was associated with poor long-term swallow outcomes.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.de Almeida JR et al. Oncologic Outcomes After Transoral Robotic Surgery: A Multi-institutional Study. JAMA Otolaryngol.-- Head Neck Surg. 141, 1043–1051 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francis DO, Weymuller EA, Parvathaneni U, Merati AL & Yueh B. Dysphagia, stricture, and pneumonia in head and neck cancer patients: does treatment modality matter? Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol 119, 391–397 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dziegielewski PT et al. Transoral Robotic Surgery for Oropharyngeal Cancer: Long-term Quality of Life and Functional Outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg 139, 1099 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutcheson KA, Holsinger FC, Kupferman ME & Lewin JS Functional outcomes after TORS for oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol 272, 463–471 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha P, Haughey BH, Kallogjeri D. & Jackson RS Long-term analysis of transorally resected p16 + Oropharynx cancer: Outcomes and prognostic factors. The Laryngoscope (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pauloski BR et al. Surgical variables affecting swallowing in patients treated for oral/oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck 26, 625–636 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCombe D, Lyons B, Winkler R. & Morrison W. Speech and swallowing following radial forearm flap reconstruction of major soft palate defects. Br. J. Plast. Surg 58, 306–311 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elfring T. et al. The relationship between lingual and hypoglossal nerve function and quality of life in head and neck cancer. J. Oral Rehabil 41, 133–140 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AbuRahma AF & Lim RY Management of vagus nerve injury afer carotid endarterectomy. Surgery 119, 245–247 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laverick S, Lowe D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED & Rogers SN The impact of neck dissection on health-related quality of life. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg 130, 149–154 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edge SB & Compton CC The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann. Surg. Oncol 17, 1471–1474 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rich JT et al. Transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) +/− adjuvant therapy for advanced stage oropharyngeal cancer: outcomes and prognostic factors. The Laryngoscope 119, 1709–1719 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rich JT, Liu J. & Haughey BH Swallowing function after transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) ± adjuvant therapy for advanced-stage oropharyngeal cancer. The Laryngoscope 121, 2381–2390 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinha P, Pipkorn P, Zenga J. & Haughey BH The Hybrid Transoral-Pharyngotomy Approach to Oropharyngeal Carcinoma: Technique and Outcome. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol 126, 357–364 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L. & Spitznagel EL Jr. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA 291, 2441–2447 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salassa JR A functional outcome swallowing scale for staging oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dig. Dis. Basel Switz 17, 230–234 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neely JG et al. Practical Guide to Understanding Multivariable Analyses, Part B: Conjunctive Consolidation. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg 148, 359–365 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haughey BH et al. Transoral laser microsurgery as primary treatment for advanced-stage oropharyngeal cancer: A united states multicenter study. Head Neck 33, 1683–1694 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iseli TA et al. Functional Outcomes after Transoral Robotic Surgery for Head and Neck Cancer, Functional Outcomes after Transoral Robotic Surgery for Head and Neck Cancer. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg 141, 166–171 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuo K. & Palmer JB Anatomy and Physiology of Feeding and Swallowing – Normal and Abnormal. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am 19, 691–707 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiley SG, Hargunani CA, Skoner JM, Holland JM & Wax MK Swallowing function after chemoradiation for advanced stage oropharyngeal cancer. Otolaryngol.--Head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg 134, 455–459 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisbruch A. et al. Chemo-IMRT of oropharyngeal cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: swallowing organs late complication probabilities and dosimetric correlates. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys 81, e93–99 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng FY et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy of head and neck cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: early dose-effect relationships for the swallowing structures. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys 68, 1289–1298 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levendag PC et al. Dysphagia disorders in patients with cancer of the oropharynx are significantly affected by the radiation therapy dose to the superior and middle constrictor muscle: A dose-effect relationship. Radiother. Oncol 85, 64–73 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen K, Lambertsen K. & Grau C. Late swallowing dysfunction and dysphagia after radiotherapy for pharynx cancer: Frequency, intensity and correlation with dose and volume parameters. Radiother. Oncol 85, 74–82 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisbruch A. et al. Dysphagia and aspiration after chemoradiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: Which anatomic structures are affected and can they be spared by IMRT? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol 60, 1425–1439 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.More YI et al. Functional swallowing outcomes following transoral robotic surgery vs primary chemoradiotherapy in patients with advanced-stage oropharynx and supraglottis cancers. JAMA Otolaryngol.-- Head Neck Surg 139, 43–48 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owadally W. et al. PATHOS: a phase II/III trial of risk-stratified, reduced intensity adjuvant treatment in patients undergoing transoral surgery for Human papillomavirus (HPV) positive oropharyngeal cancer. BMC Cancer 15, 602 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rieger JM et al. Functional outcomes after surgical reconstruction of the base of tongue using the radial forearm free flap in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 29, 1024–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seikaly H. et al. Functional outcomes after primary oropharyngeal cancer resection and reconstruction with the radial forearm free flap. The Laryngoscope 113, 897–904 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winter SCA, Cassell O, Corbridge RJ, Goodacre T. & Cox GJ Quality of life following resection, free flap reconstruction and postoperative external beam radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the base of tongue1. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci 29, 274–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connell D. et al. Primary surgery versus chemoradiotherapy for advanced oropharyngeal cancers: a longitudinal population study. J. Otolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. J. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Chir. Cervico-Faciale 42, 31 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kano S. et al. Matched-pair analysis in patients with advanced oropharyngeal cancer: surgery versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Oncology 84, 290–298 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zenga J. et al. Treatment Outcomes for T4 Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol.-- Head Neck Surg 141, 1118–1127 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ang KK et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 363, 24–35 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farri A, Accornero A. & Burdese C. Social importance of dysphagia: its impact on diagnosis and therapy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. Organo Uff. Della Soc. Ital. Otorinolaringol. E Chir. Cerv.-facc 27, 83–86 (2007). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terrell JE et al. Clinical predictors of quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg 130, 401–408 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Deiry MW, Futran ND, McDowell JA, Weymuller EA Jr & Yueh B. Influences and Predictors of Long-term Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer Survivors. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg 135, 380–384 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]