Abstract

Aims:

Our primary objective was to determine whether all-cause rates of mortality and resource utilization were higher during periods of diabetic foot ulceration. In support of this objective, a secondary objective was to develop and validate an episode-of-care model for diabetic foot ulceration.

Methods:

We evaluated data from the Medicare Limited Data Set between 2013 and 2019. We defined episodes-of-care by clustering diabetic foot ulcer related claims such that the longest time interval between consecutive claims in any cluster did not exceed a duration which was adjusted to match two aspects of foot ulcer episodes that are well-established in the literature: healing rate at 12 weeks, and reulceration rate following healing. We compared rates of outcomes during periods of ulceration to rates immediately following healing to estimate incidence ratios.

Results:

The episode-of-care model had a minimum mean relative error of 4.2% in the two validation criteria using a clustering duration of seven weeks. Compared to periods after healing, all-cause inpatient admissions were 2.8 times more likely during foot ulcer episodes and death was 1.5 times more likely.

Conclusions:

A newly-validated episode-of-care model for diabetic foot ulcers suggests an underappreciated association between foot ulcer episodes and all-cause resource utilization and mortality.

Keywords: Diabetic foot ulcers, Episodes of care, Amputations, Resource utilization, Hospitalizations, Prevention

1. Introduction

Defining episodes-of-care is an important and evolving part of modern healthcare economics. Traditionally, there have been two approaches for defining episodes-of-care. The first evaluates care included beyond an initial event or procedure to include associated aftercare within a predefined time window. The second approach collects care-related information over a period of time for a specific chronic condition identified by a set of administrative codes.

While these approaches are useful, they are inadequate for more complex chronic conditions where care extends beyond an initial event and may be associated, in part or whole, with a broad set of administrative codes. In such cases, a simple attribution of the resource utilization directly related to the chronic condition is incomplete, limiting the applicability of these approaches. Diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are a condition for which a more comprehensive approach for estimating episodes-of-care is needed to properly assess and attribute economic burden.

While several methods have been validated to estimate prevalence of DFU from administrative data, we are unaware of any validated method for estimating DFU incidence or episodes-of-care.[1] Furthermore, several studies of DFU and its association with mortality suggest that foot ulceration may not be an innocent bystander of a multi-morbid disease process but instead an accomplice, complicating attribution of resource utilization and costs. A meta-analysis by Saluja and colleagues synthesized data from 11 studies that reported 84,000 all-cause deaths in approximately 450,000 participants with diabetes over 650,000 person-years. These authors found that foot ulcers were associated with a substantial increase in risk for all-cause mortality (pooled RR = 2.45).[2]

The purpose of the present investigation is two-fold: (1) to validate a claims-based episode-of-care model for DFU; and (2) to apply this model to determine whether the rates of significant healthcare economic outcomes, such as all-cause mortality and all-cause inpatient admissions, are higher during DFU episodes-of-care.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design, approval, and reporting

This was a cohort study of administrative data collected between 2013 and 2019. It was reviewed by the Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (BRANY) Independent Review Board (IRB) and determined to be exempt because the data were previously collected, are deidentified, and are publicly-available. This research was also subject to the Medicare limited data set (LDS) data use agreement (DUA). BRANY IRB granted a waiver of informed consent because contact with beneficiaries is not permitted under the LDS DUA.

This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.[3]

2.2. Data provenance and population

This was a population-based study. We used inpatient institutional, outpatient institutional, and provider fee-for-service (carrier) claims data from the Medicare LDS sample from 2013 to 2019. The LDS consists of publicly-available and deidentified data on physician-beneficiary and institution-beneficiary interactions within the United States. Our data contained claims spanning 11,638,371 beneficiary-years for 3,982,684 unique Medicare beneficiaries. We analyzed 379,731,127 medical claims, each of which had 2.9 associated diagnosis codes on average.

2.3. Episodes-of-care definition

We defined DFU episodes-of-care by grouping clusters of DFU-related claims such that the longest time interval between consecutive claims in any cluster did not exceed a predefined clustering duration. A claim was judged to be DFU-related if it contained any of the following diagnosis codes (see also eTable 1), irrespective of the order in which the diagnosis code was listed on the claim: ICD-9 (707.10, 707.14, 707.15, 707.19, 707.9), and ICD-10 (E08.621, E09.621, E10.621, E11.621, E13.621). These codes are consistent with those used by Harrington and colleagues,[4] whose method for estimating DFU prevalence was independently found to have 94% sensitivity and 91% specificity.[1] We only included patients with a history of diabetes mellitus, consistent with the Charlson Comorbidity definition. Only those episodes with more than one associated DFU-related claim were considered.

2.4. Model adjustment and validation

We adjusted the episode-of-care clustering duration to match two aspects of DFU episodes that are well-established in the literature.

Fife and colleagues[5] reported 12 week DFU healing rates at 30.5% based on data from the U.S. Wound Registry (USWR), a source of real-world data for wound healing. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has designated USWR to be a Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). We compared percentages of DFU episodes shorter than 12 weeks to this 30.5% benchmark.

We also compared the reulceration rates at one, two, and three years post-healing to rates reported in the literature for those receiving standard diabetic foot care. We referenced a survey by Armstrong and colleagues[6] to identify relevant studies and used data from those observational studies and from control groups of those experimental studies that reported on reulceration indexed from healing. We calculated an average of these rates over the studies[7–11] weighted by study cohort size. The one, two, and three year target reulceration rates from the literature were found to be 36.1%, 46.8%, and 54.6% respectively. We estimated the reulceration rate from the DFU episode model by performing a Kaplan-Meier analysis on the duration between the healing date of the first DFU and the incident date of second DFU episode identified (or between the healing date of the first DFU and the date of the beneficiary’s last claim, if censored).

We evaluated the agreement between the estimates of these four values from our DFU episode-of-care model to these target values by varying the clustering duration from 2 weeks to 20 weeks in half week increments and evaluating the mean relative error, our secondary outcome of interest.

2.5. Cohort characteristics

We used established methods to identify comorbidities in beneficiaries using administrative data.[12–16] Relevant conditions included risk factors for DFU development such as diabetes, peripheral neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, lower extremity amputation (LEA), vision impairments, and foot deformity. To summarize the healthcare burden and risk associated with the beneficiaries, we calculated and reported the Charlson Comorbidity Index.[12] Descriptive characteristics for race, ethnicity, and sex were reported consistent with the Medicare LDS definitions. We qualitatively compared descriptive characteristics for periods before the first diabetic foot ulcer episode-of-care to statistics for post-healing and to statistics for the end of followup. We reported the high-to-low amputation ratio, where high-level amputations were defined as more proximal than the ankle.

2.6. Association with resource utilization

We calculated rates of all-cause mortality, rates of inpatient admissions stratified by Major Diagnostic Categories (MDC) and Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG), and rates of provider encounters for periods during DFU episodes-of-care, for periods after healing, and for other periods during the beneficiary followup. MDCs and MS-DRGs summarize inpatient stays by illness for purposes of billing, and each MS-DRG is defined by a particular set of beneficiary characteristics, including diagnosis codes, procedure codes, demographics, and discharge status.

We identified periods during DFU episode-of-care using the model previously described. We used periods after DFU healing as a comparator, with each comparator period having a target duration equal to the duration of the preceding DFU. For cases in which a recurrent DFU occurred before the target duration of the after period, we truncated the after period and considered only the DFU-free period as the comparator. We divided the outcome rate during DFU episodes by the rate after healing to calculate incidence ratios, our primary outcome of interest.

We estimated uncertainty about these point-estimates of incidence rates and incidence ratios by bootstrap sampling of the cohort-level data.[17] We sampled until the reported empirical 95% confidence intervals converged to two significant digits to characterize the uncertainty in these estimates.

3. Results

3.1. Model adjustment and validation

The best agreement between the episode-of-care model and the two validation criteria was found with a clustering duration of seven weeks (eTable 2). The mean relative difference among the four comparisons was 4.2%, and the largest relative difference among the four comparisons was 7.5% for the reulceration rate at 3 years (54.6% target vs 50.6% episode-of-care estimate). The healing rate at 12 weeks from the episode-of-care model was found to be 29.2%, which agrees well with the target of 30.5% (relative difference of 4.2%). The mean duration from incident DFU to healing was 12.1 weeks (IQR: 7.1–12.9 weeks). The median duration from healing to reulceration in the Medicare cohort was approximately three years, and by six months 26.7% of DFU have recurred.

3.2. Cohort characteristics

Table 1 shows the descriptive cohort characteristics for the 78,716 beneficiaries we identified with at least one DFU episode, suggesting approximately 2% of all Medicare beneficiaries and 8.3% of those beneficiaries with diabetes mellitus have a history of DFU. Claims data for these 78,716 beneficiaries spanned 383,856 beneficiary-years.

Table 1 –

Descriptive characteristics for Medicare beneficiaries with at least one diabetic foot ulcer episode-of-care (78,716).

| Characteristics | At the Beginning of First Diabetic Foot Ulcer Episode | At the End of First Diabetic Foot Ulcer Episode | At the End of Followup | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.9 ± 12.5 | 71.1 ± 12.5 | 73.4 ± 12.3 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 5.94 ± 4.94 | 7.34 ± 4.90 | 11.0 ± 5.22 | |

| Charlson Comorbidities | ||||

| Myocardial Infarction | 17.8% | 22.2% | 36.3% | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 38.2% | 45.6% | 64.9% | |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 47.3% | 64.1% | 80.4% | |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 4.8% | 5.9% | 11.2% | |

| Diabetes without Complications | 10.8% | 12.1% | 14.5% | |

| Diabetes with Complications | 56.4% | 72.8% | 85.5% | |

| Mild or Moderate Renal Disease | 23.5% | 27.9% | 34.4% | |

| Severe Renal Disease | 18.2% | 21.8% | 32.8% | |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 36.2% | 41.9% | 58.7% | |

| Mild Liver Disease | 10.8% | 12.5% | 19.6% | |

| Moderate or Severe Liver Disease | 1.7% | 2.1% | 4.4% | |

| Hemiplegia or Paraplegia | 6.4% | 7.8% | 13.9% | |

| Dementia | 16.7% | 20.6% | 36.4% | |

| Rheumatic Disease | 8.2% | 9.3% | 13.4% | |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 27.1% | 31.2% | 43.6% | |

| Any Malignancy | 12.1% | 13.4% | 17.9% | |

| Metastatic Solid Tumor | 2.0% | 2.4% | 5.4% | |

| HIV Infection | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | |

| Most Proximal Lower Extremity Amputation | ||||

| Digit | 2.4% | 4.6% | 6.8% | |

| Foot (non-digit) | 1.3% | 3.5% | 6.0% | |

| Below Knee | 0.5% | 1.9% | 4.3% | |

| Above Knee | 0.6% | 1.6% | 3.8% | |

| Foot Deformities | ||||

| Hallux Valgus | 2.4% | 3.7% | 8.7% | |

| Charcot Neuroarthropathy | 2.0% | 3.6% | 6.8% | |

| Pes Planus | 1.2% | 1.7% | 3.3% | |

| Hallux Rigidus | 1.2% | 1.7% | 3.1% | |

| Hallux Varus | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.7% | |

| Other DFU Risk Factors | ||||

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 40.8% | 57.2% | 71.2% | |

| Diabetic Retinopathy | 17.6% | 20.4% | 27.2% | |

| Diabetic Macular Edema | 6.2% | 6.8% | 9.6% | |

| Cataracts | 22.6% | 24.8% | 37.5% | |

| Glaucoma | 16.8% | 18.5% | 25.7% | |

| Blindness | 4.2% | 5.2% | 9.3% | |

| Any Vision Impairment | 42.6% | 47.6% | 63.3% | |

| Depression | 27.9% | 33.6% | 50.4% | |

| Nicotine Dependence | 25.3% | 31.3% | 52.7% | |

| Obesity | 87.2% | 93.6% | 94.7% | |

According to the Medicare LDS definitions, approximately 77.5% of the cohort with at least one DFU was White, 14.7% was Black, and 3.3% identified as Hispanic. A majority (56.2%) of the cohort was male, according to the Medicare LDS definition.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index for this cohort increased by 23.6% during the first DFU episode-of-care, with large relative increases in the rates of diagnosis codes for myocardial infarction (24.7%), congestive heart failure (19.4%), and peripheral vascular disease (35.5%). Similarly, rates of LEA more than doubled in the cohort over the first DFU episode-of-care. Approximately 21% of those with DFU history had some level amputation by the end of followup, and the high-to-low amputation ratio was 64%.

3.3. Episode characteristics

A total of 206,203 episodes were identified in the 78,716 beneficiaries with at least one DFU episode, (54 DFU per 100 beneficiary-years), implying an average of 2.6 DFU/beneficiary over followup. Among those beneficiaries with diabetes, the incidence was 4.6 DFU per 100 beneficiary-years. Approximately 50% of the 78,716 beneficiaries in the data with at least one DFU experienced one or more recurrence in the period from 2013 to 2019. Among those beneficiaries with at least one DFU, there were 47,843 DFU-years, implying approximately 12.5% of these beneficiaries’ followup were marked by treatment for a DFU.

During DFU episodes, 10,997 beneficiaries died (5.3%). Approximately 34.8% of DFU episodes (71,834) included at least one inpatient admission, with a total of 120,245 admissions occurring during episodes (2.5 admissions/DFU-year). LEAs were also common during foot ulcer episodes, with 19,358 of DFU episodes (9.4%) having at least one LEA.

3.4. Association with resource utilization

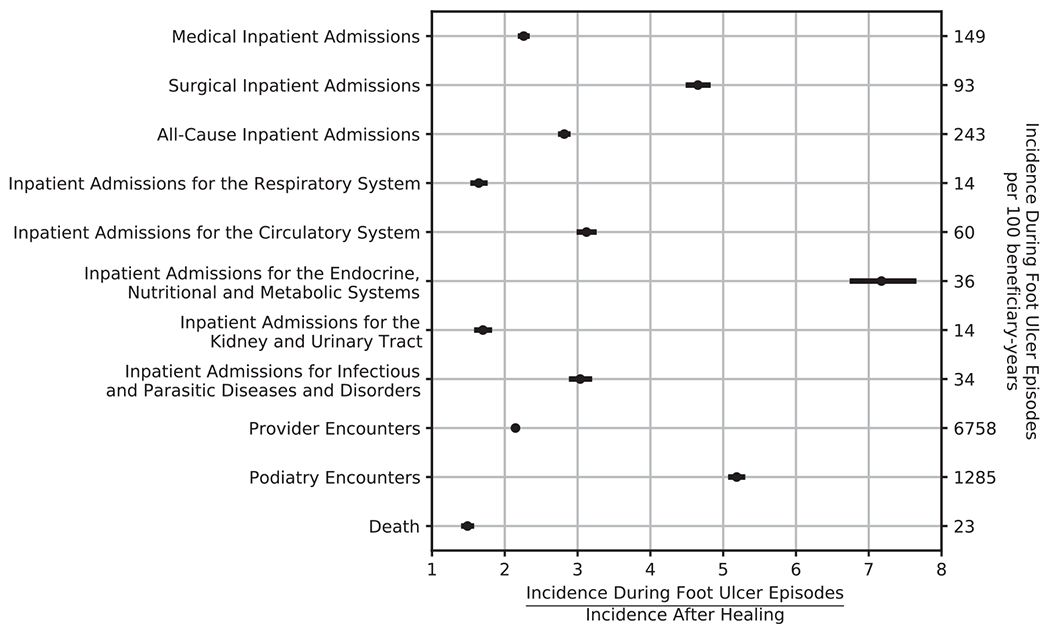

Fig. 1 summarizes the incidence ratios for select resource utilization. During DFU episodes, all-cause mortality was 50% more likely (IR = 1.5; CI: 1.44–1.54), and all-cause inpatient admission was nearly three times more likely (IR = 2.8; CI: 2.77–2.87) compared to periods after healing. Provider (IR = 2.2) and podiatry (IR = 5.2) ambulatory encounters were more common during DFU episodes-of-care. To allow comparison against the case-controlled association between DFU and mortality reported by Saluja and colleagues,[2] we calculated the incidence ratio of the rate of mortality following incidence of the first DFU to the rate of mortality all-time in those with at least one DFU and found it to be 2.2 (CI: 2.15–2.24).

Fig. 1 –

Increased Rates of Mortality and Healthcare Resource Utilization during Diabetic Foot Ulcer Episodes-of-Care Compared to Periods After Healing.

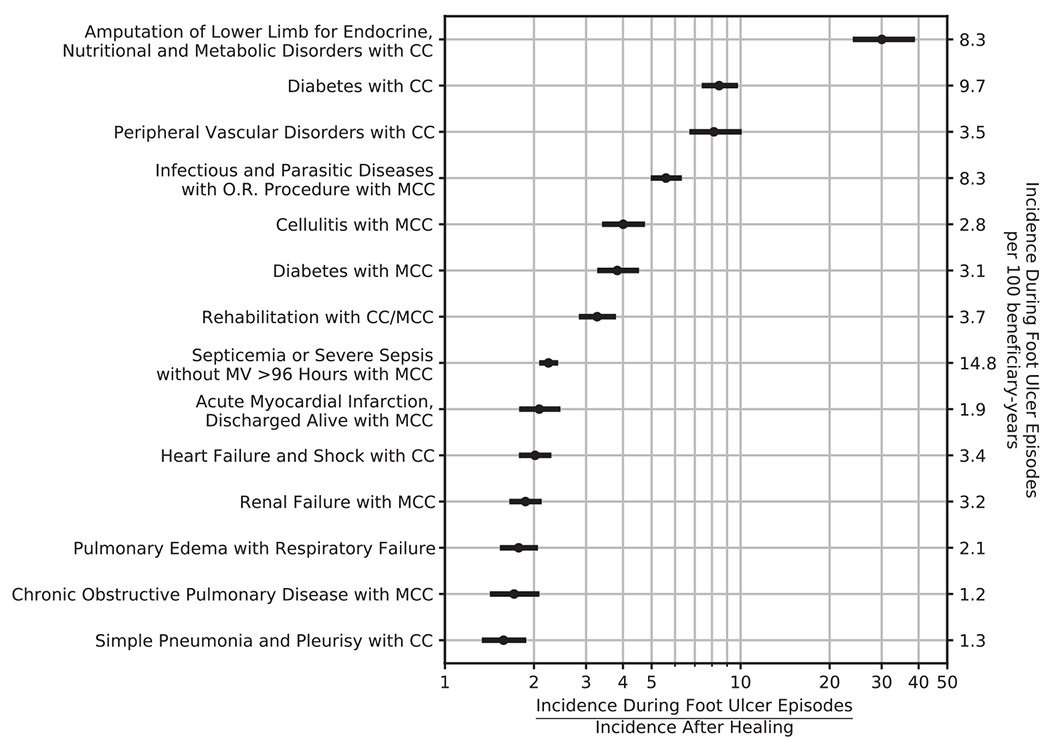

Fig. 2 summarizes the incidence ratios for select MS-DRGs. Compared to periods after healing, we observed higher rates during DFU episodes for admissions commonly associated with DFU (eg, amputation of lower limb for endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic disorders with complication of comorbidity, IR = 30.0, or cellulitis with major complication or comorbidity, IR = 4.1) and for conditions less commonly thought to be associated with DFU (eg, for heart failure and shock with complication or comorbidity, IR = 2.0, and for renal failure with complication or comorbidity, IR = 1.9).

Fig. 2 –

Increased Rates of Admission for Select Medicare-Severity Diagnosis Related Codes during Diabetic Foot Ulcer Episodes-of-Care Compared to Periods After Healing.

Table 2 shows the incidence and incidence ratios for each of the thirty most common MS-DRGs in these 78,716 beneficiaries. All but one of the top thirty admission MS-DRGs had higher rates during DFU episodes than after episodes. The exception was hip and knee joint replacement, which may have had lower incidence during DFU episodes because it is an elective procedure that may be delayed until post-healing. For many of these MS-DRG, such as for heart failure and shock with complication or comorbidity (IR = 2.0; CI: 1.8–2.2), rates are only elevated only during DFU episodes-of-care (3.4 per 100 beneficiary-years) and are nearly equivalent in the period after healing (1.69 per 100 beneficiary-years) and during other periods of followup (1.64 per 100 beneficiary-years).

Table 2 –

Rates of Inpatient Admissions During and After Diabetic Foot Ulcer Episodes-of-Care for the Most Common Major Diagnostic Categories and Medicare-Severity Diagnosis Related Groups.

| DRG | Description | Number of Admissions | Admission Rate, per 100 beneficiary-years |

During-to-After Incidence Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During DFU Episodes | After DFU Episodes | Other Periods | ||||

| All-Cause Admissions | 389,895 | 243 (240–245) | 86.2 (84.7–87.7) | 79.2 (78.4–79.9) | 2.82 (2.77–2.87) | |

| Medical Admissions | 284,695 | 149 (147–150) | 65.7 (64.4–67.0) | 61.8 (61.2–62.4) | 2.26 (2.22–2.30) | |

| Surgical Admissions | 101,854 | 93.1 (91.9–94.2) | 20.0 (19.4–20.6) | 16.7 (16.5–16.9) | 4.65 (4.52–4.79) | |

| Diseases and Disorders of the Respiratory System | 35,844 | 13.8 (13.4–14.3) | 8.41 (8.03–8.79) | 8.46 (8.28–8.64) | 1.64 (1.56–1.73) | |

| Diseases and Disorders of the Circulatory System | 89,894 | 59.8 (58.8–60.8) | 19.2 (18.6–19.7) | 17.8 (17.5–18.0) | 3.12 (3.03–3.22) | |

| Diseases and Disorders of the Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue | 36,863 | 23.1 (22.5–23.6) | 8.81 (8.42–9.21) | 7.43 (7.3–7.55) | 2.62 (2.50–2.74) | |

| Diseases and Disorders of the Skin, Subcutaneous Tisue and Breast | 19,059 | 15.8 (15.3–16.2) | 3.85 (3.61–4.1) | 3.35 (3.27–3.44) | 4.09 (3.84–4.38) | |

| Diseases and Disorders of the Endocrine, Nutritional and Metabolic System | 30,608 | 35.6 (34.9–36.4) | 4.97 (4.67–5.26) | 4.0 (3.89–4.12) | 7.17 (6.78–7.62) | |

| Diseases and Disorders of the Kidney and Urinary Tract | 32,623 | 13.8 (13.4–14.2) | 8.11 (7.73–8.5) | 7.52 (7.37–7.67) | 1.70 (1.62–1.79) | |

| Infectious and Parasitic Diseases and Disorders | 45,631 | 34.3 (33.6–35.0) | 11.3 (10.9–11.7) | 8.31 (8.16–8.45) | 3.04 (2.92–3.16) | |

| 871 | Septicemia or Severe Sepsis without MV > 96 Hours with MCC | 24,619 | 14.8 (14.3–15.2) | 6.59 (6.3–6.9) | 4.99 (4.9–5.1) | 2.24 (2.1–2.4) |

| 291 | Heart Failure and Shock with MCC or Peripheral Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) | 16,143 | 7.83 (7.5–8.2) | 4.27 (4.0–4.6) | 3.55 (3.4–3.7) | 1.83 (1.7–2.0) |

| 603 | Cellulitis without MCC | 9,925 | 7.74 (7.4–8.0) | 1.90 (1.7–2.1) | 1.83 (1.8–1.9) | 4.07 (3.7–4.5) |

| 638 | Diabetes with CC | 7,866 | 9.68 (9.3–10.0) | 1.14 (1.0–1.3) | 0.97 (0.91–1.0) | 8.46 (7.5–9.6) |

| 292 | Heart Failure and Shock with CC | 7,281 | 3.41 (3.2–3.6) | 1.69 (1.5–1.9) | 1.64 (1.6–1.7) | 2.02 (1.8–2.2) |

| 853 | Infectious and Parasitic Diseases with O.R. Procedure with MCC | 7,116 | 8.29 (8.0–8.6) | 1.48 (1.3–1.6) | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | 5.59 (5.1–6.2) |

| 683 | Renal Failure with CC | 6,720 | 3.16 (3.0–3.3) | 1.63 (1.5–1.8) | 1.51 (1.5–1.6) | 1.94 (1.7–2.1) |

| 872 | Septicemia or Severe Sepsis without MV > 96 Hours without MCC | 6,639 | 4.35 (4.1–4.6) | 1.53 (1.4–1.7) | 1.31 (1.3–1.4) | 2.84 (2.6–3.2) |

| 682 | Renal Failure with MCC | 6,431 | 3.16 (3.0–3.3) | 1.69 (1.5–1.8) | 1.41 (1.4–1.5) | 1.87 (1.7–2.1) |

| 885 | Psychoses | 5,779 | 1.56 (1.4–1.7) | 1.03 (0.9–1.2) | 1.48 (1.3–1.6) | 1.50 (1.3–1.7) |

| 945 | Rehabilitation with CC/MCC | 5,530 | 3.66 (3.5–3.9) | 1.12 (1.0–1.2) | 1.11 (1.1–1.1) | 3.27 (2.9–3.7) |

| 690 | Kidney and Urinary Tract Infections without MCC | 5,415 | 1.70 (1.6–1.8) | 1.18 (1.1–1.3) | 1.35 (1.3–1.4) | 1.44 (1.3–1.6) |

| 193 | Simple Pneumonia and Pleurisy with MCC | 5,140 | 2.09 (2.0–2.2) | 1.30 (1.2–1.4) | 1.19 (1.2–1.2) | 1.61 (1.4–1.8) |

| 189 | Pulmonary Edema and Respiratory Failure | 4,919 | 2.12 (2.0–2.3) | 1.19 (1.1–1.3) | 1.11 (1.1–1.2) | 1.78 (1.6–2.0) |

| 252 | Other Vascular Procedures with MCC | 4,584 | 4.52 (4.3–4.7) | 0.93 (0.82–1.1) | 0.70 (0.67–0.74) | 4.84 (4.3–5.6) |

| 470 | Major Hip and Knee Joint Replacement or Reattachment of Lower Extremity without MCC | 4,551 | 0.75 (0.67–0.83) | 0.80 (0.70–0.90) | 1.25 (1.2–1.3) | 0.94 (0.8–1.1) |

| 617 | Amputation of Lower Limb for Endocrine, Nutritional and Metabolic Disorders with CC | 4,231 | 8.34 (8.1–8.6) | 0.28 (0.22–0.34) | 0.096 (0.085–0.11) | 30.0 (24.5–38.1) |

| 640 | Miscellaneous Disorders of Nutrition, Metabolism, Fluids and Electrolytes with MCC | 4,191 | 1.89 (1.7–2.1) | 1.16 (1.0–1.3) | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 1.62 (1.4–1.9) |

| 280 | Acute Myocardial Infarction, Discharged Alive with MCC | 3,971 | 1.88 (1.7–2.0) | 0.90 (0.79–1.0) | 0.90 (0.85–0.93) | 2.08 (1.8–2.4) |

| 253 | Other Vascular Procedures with CC | 3,928 | 5.44 (5.2–5.7) | 0.50 (0.42–0.58) | 0.40 (0.38–0.43) | 10.9 (9.3–13.0) |

| 194 | Simple Pneumonia and Pleurisy with CC | 3,731 | 1.28 (1.2–1.4) | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | 0.91 (0.88–0.95) | 1.58 (1.4–1.8) |

| 190 | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases with MCC | 3,728 | 1.18 (1.1–1.3) | 0.69 (0.59–0.79) | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 1.71 (1.4–2.0) |

| 637 | Diabetes with MCC | 3,685 | 3.10 (2.9–3.3) | 0.81 (0.7–0.93) | 0.64 (0.59–0.68) | 3.83 (3.3–4.4) |

| 392 | Esophagitis, Gastroenteritis and Miscellaneous Digestive Disorders without MCC | 3,644 | 1.15 (1.0–1.3) | 0.70 (0.6–0.8) | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | 1.65 (1.4–2.0) |

| 689 | Kidney and Urinary Tract Infections with MCC | 3,639 | 1.43 (1.3–1.5) | 0.97 (0.86–1.1) | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | 1.47 (1.3–1.7) |

| 378 | G.I. Hemorrhage with CC | 3,521 | 1.38 (1.3–1.5) | 0.71 (0.61–0.81) | 0.84 (0.8–0.88) | 1.96 (1.7–2.3) |

| 698 | Other Kidney and Urinary Tract Diagnoses with MCC | 3,513 | 1.54 (1.4–1.7) | 0.97 (0.85–1.1) | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) | 1.59 (1.4–1.8) |

| 602 | Cellulitis with MCC | 3,349 | 2.80 (2.6–3.0) | 0.70 (0.61–0.8) | 0.58 (0.55–0.61) | 4.01 (3.5–4.6) |

| 314 | Other Circulatory System Diagnoses with MCC | 3,292 | 1.72 (1.6–1.9) | 0.91 (0.79–1.0) | 0.70 (0.66–0.74) | 1.90 (1.6–2.2) |

| 300 | Peripheral Vascular Disorders with CC | 2,963 | 3.48 (3.3–3.7) | 0.43 (0.36–0.51) | 0.39 (0.37–0.41) | 8.12 (6.9–9.9) |

Parenthesized values 95% confidence intervals; CC: complication or comorbidity; MCC: major complication or comorbidity; MV: mechanical ventilation.

4. Discussion

This study is the first of its kind to identify incident episodes-of-care for DFU from administrative data and use these to estimate associations between ulceration and all-cause rates of mortality and resource utilization. Beneficiaries with history of at least one DFU experienced high incidence (54 DFU per 100 beneficiary-years) and recurrence (median duration to recurrence of approximately three years, with 35.7% recidivism in the first year after healing). During foot ulcer episodes-of-care, all-cause inpatient admission was 2.8 times more likely and death was 1.5 times more likely compared to periods following healing in the same beneficiaries.

In many ways, our results are consistent with previous literature characterizing DFU. The most comparable mortality incidence ratio we reported (IR = 2.2) is well within the 95% confidence interval reported by Saljua and colleagues (CI: 1.85–2.85).[2] Margolis and colleagues[18] reported an annual prevalence of DFU among Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes of approximately 8%, consistent with our estimate of 8.3%. Unsurprisingly, our results also agree well with data on DFU healing rates and recurrence after healing because we tuned our episode-of-care model to match these parameters. Our work also extends that of Mehta and colleagues,[19] who presented an unvalidated episode-of-care model for DFU and used this model to estimate attributable costs for several DFU-related codes.

We observed that DFU episodes-of-care had a broad association with all-cause mortality and inpatient admissions, including for conditions not commonly thought to be associated with DFU such as heart failure (IR = 2.0), renal failure (IR = 1.9), myocardial infarction (IR = 2.1), and pulmonary edema (IR = 1.8). Brownrigg and colleagues,[20] who reported similar findings for diabetic foot ulceration and its independent association with all-cause mortality, hypothesized several possible physiological mechanisms for such findings, including near-term consequences of DFU such as severe sepsis (IR = 2.2) and its sequelae, such as multiorgan failure, and long-term consequences to the cardiovascular and renal systems from chronic inflammation associated with DFU.

Our results suggest that provision of comprehensive preventive care to arrest development of DFU in high-risk populations may impact healthcare outcomes beyond those traditionally associated with diabetic foot syndrome. Evidence-based and recommended preventive care includes [21] routine foot exam by a specialist provider, use of appropriate therapeutic footwear to be worn by the patient at all times, structured education for the patient on self-care, daily self-exams by the patient, aggressive and prompt treatment of pre-ulcerative lesions such as callus and blister, and once-daily foot temperature monitoring to identify inflammation preceding DFU. Many of these recommended practices were recently incorporated into a study of real-world practice conducted by Isaac and colleagues, who reported large reductions in all-cause inpatient admissions (RRR = 52%).[22] Another study found that patients with a preventative foot exam in the last year had lower odds (OR = 0.67, CI: 0.46–0.96) of being hospitalized for any cause within that year.[23]

One strength of our study is that we estimated attributable resource utilization without identifying a matched cohort. While a case-control approach is most commonly used to quantify association between risk factors and outcomes, we used our episode-of-care model to compare intervals during and after DFU healing for each beneficiary, implicitly accounting for overall trends in resource utilization and mortality rates that may exist with aging and disease progression. We adopted this approach for two reasons. First, other researchers[24] have reported challenges identifying propensity-matched controls for patients at-risk for DFU. Second, our approach allows us to better isolate the impact of DFU temporally on specific outcomes of interest because we are comparing periods with and without DFU in the same cases instead of comparing cases with DFU to cases without DFU, which is less temporally-specific to the episode-of-care.

5. Limitations

Several aspects of our work warrant additional consideration. First, we validated our episode-of-care model against aggregate results from the literature. Another approach would be to prospectively validate the episodes-of-care model against clinical data in the medical records. For a suitably large and representative cohort, such an approach would represent the gold-standard for validating our model.

Second, a major limitation of our episodes-of-care model is that we are unable to distinguish between multiple concurrent DFU. While ICD-10 diagnosis codes partially address this limitation by allowing coders to specify laterality and location, our seven-year data set spans usage of both ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Furthermore, use of laterality in ICD-10 codes can be inconsistent, limiting utility of these indicators.

Finally, we inherited all limitations traditionally associated with use of Medicare LDS data. These include under-diagnosis of chronic conditions in real-world practice, the disparity between care received and care needed, lack of clinical context related to diagnosis and procedure codes reported on claims, inaccuracies related to financial incentives because claims are tied to potential reimbursement, and limited generalizability because the LDS cohort is comprised predominantly of white Americans older than 65 years of age.

6. Conclusions

A newly-validated episode-of-care model for diabetic foot ulceration suggests an underappreciated association between diabetic foot ulcer prevalence, all-cause mortality (IR = 1.5), and all-cause inpatient admissions (IR = 2.8). Diabetic foot ulceration increases the likelihood of inpatient admission for cardiovascular, renal, and pulmonary complications, with DFU potentially triggering a sinister cascade of excess acute-on-chronic complications. Our results suggest that a renewed focus on prevention of diabetic foot complications may be warranted and that such efforts may have broader than anticipated impact on health outcomes.

Funding

Petersen, Salgado, and Bloom disclose partial funding from Podimetrics, Inc. for the analysis of data and preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Petersen, Salgado, and Bloom are employees and shareholders of Podimetrics Inc. Linde-Zwirble has previously consulted for Podimetrics Inc. Rothenberg is a consulting medical director for Podimetrics Inc. Armstrong is on the scientific advisory board of Podimetrics Inc. Armstrong and Tan disclose funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases (Armstrong under 1R01124789-01A1, and Tan under 1K23DK122126-03).

Data availability

The data underlying this study belong to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Data are available to all researchers following a standard application process and signing of a data use agreement. The authors paid a fee to access the CMS data used in this study, with a fee schedule in accordance with CMS policies. Further instructions for submitting an application to purchase access to the Medicare Limited Data Set can be found at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/LimitedDataSets

REFERENCES

- [1].Sohn M-W, Budiman-Mak E, Stuck RM, Siddiqui F, Lee TA. Diagnostic accuracy of existing methods for identifying diabetic foot ulcers from inpatient and outpatient datasets. J Foot Ankle Res 2010;3:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Saluja S, Anderson SG, Hambleton I, Shoo H, Livingston M, Jude EB, et al. Foot ulceration and its association with mortality in diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2020;37(2):211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(8):573. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Harrington C, Zagari MJ, Corea J, Klitenic J. A cost analysis of diabetic lower-extremity ulcers. Diabetes Care 2000;23 (9):1333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fife CE, Eckert KA, Carter MJ. Publicly reported wound healing rates: the fantasy and the reality. Adv Wound Care 2018;7 (3):77–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ingelfinger JR, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med 2017;376 (24):2367–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Apelqvist J, Larsson J, Agardh CD. Long-term prognosis for diabetic patients with foot ulcers. J Intern Med 1993;233 (6):485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Plank J, Haas W, Rakovac I, Gorzer E, Sommer R, Siebenhofer A, et al. Evaluation of the impact of chiropodist care in the secondary prevention of foot ulcerations in diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 2003;26(6):1691–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pound N, Chipchase S, Treece K, Game F, Jeffcoate W. Ulcer-free survival following management of foot ulcers in diabetes. Diabet Med 2005;22(10):1306–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dubský M, Jirkovská A, Bem R, Fejfarová V, Skibová J, Schaper NC, et al. Risk factors for recurrence of diabetic foot ulcers: prospective follow-up analysis in the Eurodiale subgroup. Int Wound J 2013;10(5):555–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Armstrong DG, Fiorito JL, Leykum BJ, Mills JL. Clinical efficacy of the pan metatarsal head resection as a curative procedure in patients with diabetes mellitus and neuropathic forefoot wounds. Foot Ankle Spec 2012;5(4):235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Glasheen WP, Cordier T, Gumpina R, Haugh G, Davis J, Renda A. Charlson Comorbidity Index: ICD-9 Update and ICD-10 Translation. Am Health Drug Benefits 2019;12 (4):188–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee LJ, Yu AP, Cahill KE, Oglesby AK, Tang J, Qiu Y, et al. Direct and indirect costs among employees with diabetic retinopathy in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24 (5):1549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43 (11):1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].World Health Organization. ICD-10 : International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems : Tenth Revision Vol. I, Vol. I,. WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Medicode (Firm). ICD-9-CM : International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Medicode; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Efron B, Tibshirani R. Bootstrap Methods for Standard Errors, Confidence Intervals, and Other Measures of Statistical Accuracy. SSO Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnheilkd 1986;1 (1):54–75. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Margolis DJ, Malay DS, Hoffstad OJ, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, diabetic foot ulcer, and lower extremity amputation among Medicare beneficiaries, 2006 to 2008: Data Points #1. In: Data Points Publication Series. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mehta SS, Suzuki S, Glick HA, Schulman KA. Determining an episode of care using claims data. Diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetes Care 1999;22(7):1110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brownrigg JRW, Griffin M, Hughes CO, Jones KG, Patel N, Thompson MM, et al. Influence of foot ulceration on cause-specific mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Vasc Surg 2014;60(4):982–986.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bus SA, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Raspovic A, Sacco ICN, et al. Guidelines on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020;36(S1). 10.1002/dmrr.v36.S110.1002/dmrr.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Isaac AL, Swartz TD, Miller ML, Short DJ, Wilson EA, Chaffo JL, et al. Lower resource utilization for patients with healed diabetic foot ulcers during participation in a prevention program with foot temperature monitoring. BMJ Open Diabetes Research Care 2020;8(1):e001440. 10.1136/bmidrc-2020-001440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Albright RH, Fleischer AE. Association of select preventative services and hospitalization in people with diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2021;35(5):107903. 10.1016/i.idiacomp.2021.107903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rice JB, Desai U, Cummings AKG, Birnbaum HG, Skornicki M, Parsons NB. Burden of diabetic foot ulcers for medicare and private insurers. Diabetes Care 2014;37(3):651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study belong to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Data are available to all researchers following a standard application process and signing of a data use agreement. The authors paid a fee to access the CMS data used in this study, with a fee schedule in accordance with CMS policies. Further instructions for submitting an application to purchase access to the Medicare Limited Data Set can be found at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/LimitedDataSets