Abstract

Background

This meta-analysis was performed to investigate the effects of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) precursor supplementation on glucose and lipid metabolism in human body.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, CENTRAL, Web of Science, Scopus databases were searched to collect clinical studies related to the supplement of NAD+ precursor from inception to February 2021. Then the retrieved documents were screened, the content of the documents that met the requirements was extracted. Meta-analysis and quality evaluation was performed detection were performed using RevMan5.4 software. Stata16 software was used to detect publication bias, Egger and Begg methods were mainly used. The main research terms of NAD+ precursors were Nicotinamide Riboside (NR), Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN), Nicotinic Acid (NA), Nicotinamide (NAM). The changes in the levels of triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and fasting blood glucose were mainly concerned.

Results

A total of 40 articles were included in the meta-analysis, with a sample of 14,750 cases, including 7406 cases in the drug group and 7344 cases in the control group. The results of meta-analysis showed that: NAD+ precursor can significantly reduce TG level (SMD = − 0.35, 95% CI (− 0.52, − 0.18), P < 0.0001), and TC (SMD = − 0.33, 95% CI (− 0.51, − 0.14), P = 0.0005), and LDL (SMD = − 0.38, 95% CI (− 0.50, − 0.27), P < 0.00001), increase HDL level (SMD = 0.66, 95% CI (0.56, 0.76), P < 0.00001), and plasma glucose level in the patients (SMD = 0.27, 95% CI (0.12, 0.42), P = 0.0004). Subgroup analysis showed that supplementation of NA had the most significant effect on the levels of TG, TC, LDL, HDL and plasma glucose.

Conclusions

In this study, a meta-analysis based on currently published clinical trials with NAD+ precursors showed that supplementation with NAD+ precursors improved TG, TC, LDL, and HDL levels in humans, but resulted in hyperglycemia, compared with placebo or no treatment. Among them, NA has the most significant effect on improving lipid metabolism. In addition, although NR and NAM supplementation had no significant effect on improving human lipid metabolism, the role of NR and NAM could not be directly denied due to the few relevant studies at present. Based on subgroup analysis, we found that the supplement of NAD+ precursors seems to have little effect on healthy people, but it has a significant beneficial effect on patients with cardiovascular disease and dyslipidemia. Due to the limitation of the number and quality of included studies, the above conclusions need to be verified by more high-quality studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12986-022-00653-9.

Keywords: NAD+ , Nicotinic Acid, Nicotinamide, Nicotinamide mononucleotide, Nicotinamide riboside, Meta-analysis

Background

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an important cofactor of redox reaction and a central regulator of various metabolisms in the human body. It is involved in a variety of biological processes and a class of substances necessary for energy production, fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis, oxidation reaction, ATP generation, gluconeogenesis and keto generation [1, 2]. There are two major NAD+ synthesis pathways in the human body: de novo synthesis and salvage from precursors. The de novo synthesis of NAD+ converts tryptophan to quinolinic acid (QA) through the kynurenine pathway. The salvage pathways are mainly through the recovery of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), nicotinamide riboside (NR), nicotinamide (NAM), and nicotinic acid (NA). To maintain a certain level of NAD+ in the body, most NAD+ is produced by the salvage pathways, rather than de novo synthesis [3]. Sirtuins are a family of NAD+ -dependent protein deacetylases (SIRT1-7). In 1999, Frye discovered that mammalian sirtuins metabolize NAD+ [4]. Since then, sirtuins have been shown to play a major regulatory role in almost all cellular functions, participating in biological processes such as inflammation, cell growth, energy metabolism, circadian rhythm, neuronal function, aging, cancer, obesity, insulin resistance and stress response [3]. The biological role of NAD+ in humans is largely dependent on the presence of the sirtuins [5]. Recent studies have shown that decreased sirtuin6 (SIRT6) levels and function are associated with abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism [6]. Nicotinic acid reverses cholesterol transport through sirtuins-dependent deacetylation, resulting in the alternating expression of apolipoprotein, transporter, and protein, which affects human lipid metabolism [5]. Previous studies reported that niacinamide intervention had no significant effect on human lipid metabolism or increased triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels [7, 8]. However, in recent years, more and more studies have shown that NAD+ precursor nicotinamide can significantly improve the level of blood lipid in patients [9–11], suggesting a potential prospect for the treatment of hyperlipidemia. NMN also showed similar effects in mouse models, but the clinical studies on NMN intervention are limited at present, and the relationship between NMN and human lipid metabolism is not clear. Therefore, this meta-analysis was based on existing clinical trials to analyze and evaluate the effects of various NAD+ precursors supplementation on human lipid and glucose metabolism.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, Embase, CENTRAL, Web of Science, Scopus databases were searched to collect clinical studies related to the supplement of NAD+ precursor from inception to February 2021. The search was carried out by combining subject words and free words. See Additional file 1: Appendix for detailed search words.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Study content: clinical trials of NAD+ precursor supplementation; (2) Type of study: randomized controlled trial (RCT); (3) Intervention: NAD+ precursor supplementation, regardless of dose or other background therapy; control: Placebo or no therapy, and background treatment consistent with the intervention group.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Duplicate publications; (2) Animal experiments, cell experiments, reviews, conference abstracts and other literatures without available data; (3) Literatures with poor quality and obvious statistical errors.

Literature screening, data extraction and risk of bias assessment

The search, data extraction, and quality assessment were completed independently by 2 reviewers according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following information was obtained from each trial: (1) Basic information of the included studies: study title, first author, year of publication, study location, etc.; (2) Baseline characteristics of the subjects and intervention measures in the RCT study; (3) Key elements of bias risk assessment; (4) Drugs used in the trial, duration of follow-up, main outcome indicators, etc. The data collection and assessment were performed independently by two investigators, wherein any disagreements were resolved by discussion. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane handbook.

Statistical analysis

Statistical meta-analyses were performed using the RevMan5.4 software. Confidence intervals (CIs) were set at 95%. Continuous data were calculated with Standardized Mean Difference (SMD), and CIs were set at 95%, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SMD for all outcomes was calculated, using the random effect model due to the significant heterogeneity in the included studies. Stata16 software was used to detect publication bias, Egger and Begg methods were mainly used, P > 0.05 indicates no significant publication bias (because Egger examination is more sensitive when the two results are contradictory, the Egger examination results are given priority). If the change value before and after the intervention was not given in the paper, the formula ([SD change = √SD before 2 + SD after 2 − (2*R*SD before *SD after)] (R = 0.5) was used to estimate the change value.

Results

Study selection

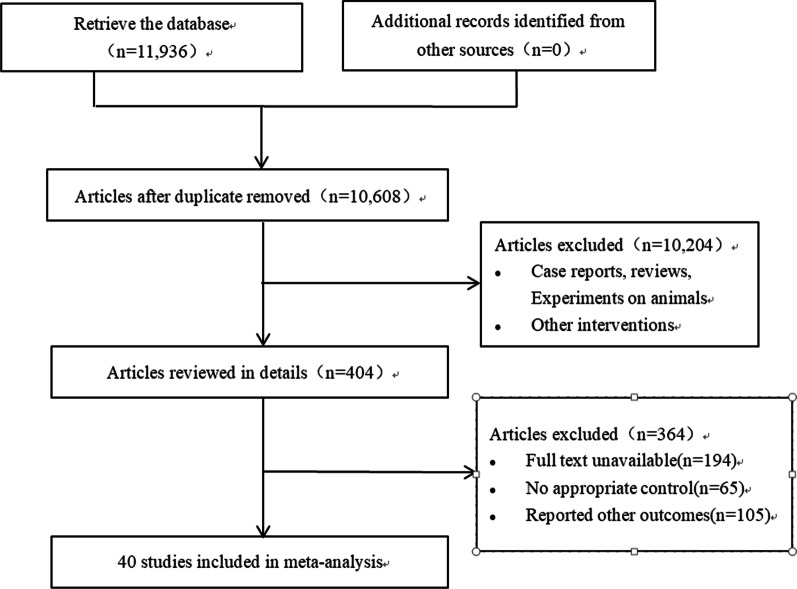

We identified 11,938 articles in the initial retrieval, including PubMed (n = 1248), Embase (n = 1088), The CENTRAL (n = 4512), Web of Science (n = 3097) and Scopus (n = 1991). Of these, 1328 duplicate articles were excluded after carefully examining the titles and abstracts. After screening, 40 studies were included in the meta-analysis, the literature screening process and results are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection

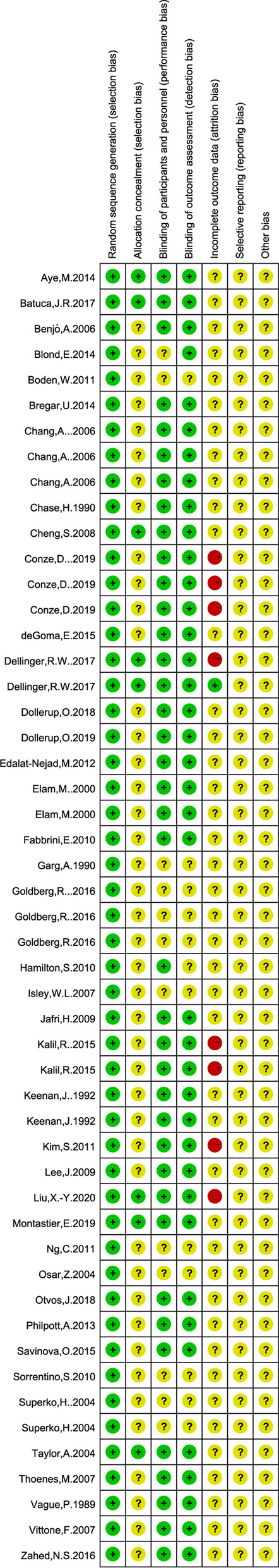

Study characteristics and quality evaluation

The baseline characteristics of studies and patients are shown in Table 1. A total of 40 articles were included, with a sample of 14,750 cases, including 7406 cases in the drug group and 7344 cases in the control group. In the included studies, there were 35 NA supplements, 3 NR supplements, 2 NAMs, and 0 NMNs. The evaluation results of bias risk are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Country | Study design | Population size | The basic characteristics Age, year BMI, kg/m2 |

Intervention | Follow-up | Subgroup classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | T | C | ||||||

| Liu, X.-Y. 2020 [9] | China | Parallel double blind | 49 | 49 | Age (T/C)55 ± 2/56 ± 2 | NAM 500–1500 mg/d | P | 52 weeks | (2) |

| Conze, D. 2019 [1] | USA | Parallel double blind | 35 | 34 |

Age (T/C)52.3 ± 5.9/50.7 ± 5.6 BMI (T/C)28 ± 2/28 ± 2 |

NR 100 mg/d | P | 56 days | (1) |

| Conze, D. 2019 [1] | USA | Parallel double blind | 35 | 34 |

Age (T/C)50.2 ± 5.8/50.7 ± 5.6 BMI (T/C)28 ± 1/28 ± 2 |

NR 300 mg/d | P | 56 days | (1) |

| Conze, D/ 2019 [1] | USA | Parallel double blind | 35 | 34 |

Age (T/C)50.9 ± 5.6/50.7 ± 5.6 BMI (T/C)28 ± 2/28 ± 2 |

NR 1000 mg/d | P | 56 days | (1) |

| Dollerup, O. 2019 [21] | Denmark | Parallel double blind | 20 | 20 |

Age (T/C)58 ± 1.6/60 ± 2.0 BMI (T/C)32.4 ± 0.5/33.3 ± 0.6 |

NR 2000 mg/d | P | 12 weeks | (6) |

| Montastier, E. 2019 [23] | France | Parallel double blind | 11 | 11 |

Patients are sedentary obese men Age (T/C)35.4 ± 2.2/35.4 ± 1.5 BMI (T/C)33.3 ± 0.7/32.6 ± 0.7 |

ERN 2000 mg/d | P | 8 weeks | (6) |

| Dollerup, O. 2018 [24] | Denmark | Parallel double blind | 20 | 20 |

Age (T/C)58 ± 1.6/60 ± 2.0 BMI (T/C)32.4 ± 0.5/33.3 ± 0.6 |

NR 2000 mg/d | P | 12 weeks | (1) |

| Otvos, J. 2018 [25] | USA | Parallel double blind | 1367 | 1387 | Age (T/C)63.5 ± 8.8/63.8 ± 8.7 | Statin + ERN | P + Statin | 1 year | (5) |

| Dellinger, R. W. 2017 [8] | Canada | Parallel double blind | 40 | 40 |

Age 60–80 BMI 18–35 |

NR 250 mg/d + PT 50 mg/d | P | 60 days | (1) |

| Dellinger, R. W. 2017 [8] | Canada | Parallel double blind | 40 | 40 |

Age 60–80 BMI 18–35 |

NR 500 mg/d + PT 100 mg/d | P | 60 days | (1) |

| Batuca, J. R. 2017 [26] | Portugal | Parallel double blind | 8 | 9 |

Age (T/C)46.13 ± 12.02/52.44 ± 9.55 BMI (T/C) 28.09 ± 4.68/29.09 ± 3.2 |

ERN 1500 mg/d | P | 12 weeks | (3) |

| Goldberg, R. 2016 [27] |

US Canada |

Parallel | 423 | 410 |

Patients with normal fasting glucose Age 62.9 ± 9.2 BMI 29.8 ± 5.0 |

ERN 2000 mg/d + simvastatin 40 mg/d | P | 1 year | (1) |

| Goldberg, R. 2016 [27] |

US Canada |

Parallel | 388 | 415 |

Patients with impaired fasting glucose Age 63.2 ± 8.7 BMI 31.0 ± 4.8 |

ERN 2000 mg/d + simvastatin 40 mg/d | P | 1 year | (4) |

| Goldberg, R. 2016 [27] |

US Canada |

Parallel | 547 | 506 |

Patients with diabetes Age 64.7 ± 8.3 BMI 32.6 ± 5.7 |

ERN 2000 mg/d + simvastatin 40 mg/d | P | 1 year | (4) |

| Zahed, N. S. 2016 [28] | Iran | Parallel double blind | 35 | 35 | Age (T/C) 49.8 ± 14.6/51.1 ± 14.1 | NA 100 mg/d | P | 8 weeks | (2) |

| Savinova, O. 2015 [29] | USA | Parallel double blind | 14 | 14 |

Patients with the Metabolic Syndrome Age (T/C)47.0 ± 11.3/49.6 ± 12.9 BMI (T/C)32.7 ± 4.6/29.8 ± 2.5 |

ERN 2000 mg/d | P | 16 weeks | (6) |

| Kalil, R. 2015 [30] | USA | Parallel double blind | 254 | 251 |

Patients with chronic kidney disease Age (T/C)70.6 ± 7.2/70.8 ± 7.4 BMI (T/C)30.9 ± 5.4/30.4 ± 5.8 |

ERN 2000 mg/d + Simvastatin 40 mg/d | P + Simvastatin 40 mg/d | 1 year | (2) |

| Kalil, R. 2015 [30] | USA | Parallel double blind | 1464 | 1444 |

Patients without chronic kidney disease Age 62.5 ± 8.4 |

ERN 2000 mg/d + Simvastatin 40 mg/d | P + Simvastatin 40 mg/d | 1 year | (3) |

| deGoma, E. 2015 [31] | USA | Parallel double blind | 5 | 3 |

Patients with coronary artery disease Age 55 |

niacin 6000 mg/d | P | 12 weeks | (5) |

| Bregar, U. 2014 [32] | The Republic of Slovenia | Parallel double blind | 33 | 30 |

Patients with coronary heart disease at least 6 months after myocardial infarction Mean age 52.5 years |

niacin/laropiprant (1000/20 mg/d for 4 weeks and 2000/40 mg/d there after) All patients were treated with statins |

P | 12 weeks | (5) |

| Blond, E. 2014 [33] | France |

cross-over Single blind |

20 | 20 |

Age 46 ± 13 BMI (T/C)31.2 ± 2.2/31.1 ± 2.2 |

ERN 2 000 mg/d | P | 8 weeks | (3) |

| Aye, M. 2014 [34] | UK | Parallel double blind | 13 | 12 |

Patients with Polycystic ovary syndrome Age (T/C)31.0 ± 6.33/31.7 ± 6.51 BMI (T/C)35.8 ± 5.55/34.8 ± 5.03 |

niacin 1000 mg/d + laropiprant 20 mg/d | P | 12 weeks | (6) |

| Philpott, A. 2013 [35] | Canada | Cross-over double blind | 66 | 66 |

Patients with coronary heart disease Age 58 ± 8.5 BMI 29.9 ± 4.4 |

ERN 1500 mg/d + atorvastatin 80 mg/d | P + atorvastatin 80 mg/d | 3 months | (5) |

| Edalat-Nejad, M. 2012 [36] | Iran | cross-over double blind | 37 | 37 | Age 57 ± 11 years | Niacin 1000 mg/d | P | 8 weeks | (2) |

| Ng, C. 2011 [37] | China | Parallel | 80 | 80 | Age (T/C) 58.34 ± 7.12/57.84 ± 8.48 | Niacin 1500 mg/d | P | 12 weeks | (3) |

| Kim, S. 2011 [38] | Korea | Parallel double blind | 25 | 22 | Age (T/C) 57.4 ± 6.8/61.8 ± 8.3 | ERN 500 mg/d for first 4 weeks and ERN 1000 mg/d for the next 4 weeks | P | 8 weeks | (3) |

| Boden, W. 2011 [39] |

USA Canada |

Parallel | 1561 | 1554 | Age (T/C) 63.7 ± 8.8/63.7 ± 8.7 | ERN 1500–2000 mg/d + Simvastatin 40–80 mg/d + Ezetimibe 10 mg/d | P + Simvastatin 40–80 mg/d + Ezetimibe 10 mg/d | 1 year | (6) |

| Fabbrini, E. 2010 [40] | USA | Parallel double blind | 9 | 9 |

Age (T/C) 43 ± 5/45 ± 3 BMI (T/C)35.8 ± 1.4/37.2 ± 2.0 |

ERN 2000 mg/d | P | 16 weeks | (6) |

| Sorrentino, S. 2010 [41] | Switzerland | Parallel double blind | 15 | 15 |

Age (T/C) 58 ± 11/62 ± 9 BMI (T/C)32 ± 4/34 ± 5 |

ERN 1500 mg/d | P | 3 months | (6) |

| Hamilton, S. 2010 [42] | Australia | Parallel double blind | 7 | 8 |

Age 65 ± 7 BMI 30 ± 5 |

Niacin 1500 mg/d | no therapy | 20 weeks | (4) |

| Lee, J. 2009 [43] | UK | Parallel double blind | 22 | 29 |

Age (T/C) 65 ± 9/65 ± 9 BMI (T/C)31 ± 5/30 ± 5 |

NA 1000 mg/d for first 4 weeks, 1500 mg/d for a further 4 weeks, and then 2000 mg/d for the remainder | P | 12 months | (6) |

| Jafri, H. 2009 [44] | USA | Parallel double blind | 27 | 27 | Age (T/C) 60 ± 10/57 ± 7 | ERN 1000 mg/d | P | 3 months | (5) |

| Cheng, S. 2008 [10] | USA | Cross-over double blind | 33 | 33 |

Hemodialysis patients with phosphorus levels > 5.0 mg/dl Age (T/C) 52.6/52.6 |

NAM 1500 mg/d | P | 8 weeks | (2) |

| Vittone, F. 2007 [45] | USA | Parallel double blind | 80 | 80 |

Age (T/C) 54.0 ± 8/53.4 ± 8 BMI (T/C) 29.7 ± 5/29.4 ± 4 |

Niacin + simvastatin | P | 3 years | (5) |

| Thoenes, M. 2007 [46] | Germany | Parallel double blind | 30 | 15 |

Patients with the metabolic syndrome Age (T/C) 34.6 ± 8.1/37.5 ± 9.6 BMI (T/C) 29.7 ± 5/29.4 ± 4 |

ERN 1000 mg/d | P | 52 weeks | (3) |

| Isley, W. L. 2007 [47] | USA | Parallel | 7 | 7 |

Age (T/C) 48 ± 14/58 ± 10 BMI (T/C) 31.7 ± 1.5/30.3 ± 2.1 |

Niacin 3000 mg/d | P | 12 weeks | (5) |

| Chang, A. 2006 [48] | USA | Cross-over double blind | 15 | 15 |

Patients with normal glucose tolerance Age 26 ± 6 BMI 25 ± 3 |

NA 2000 mg/d | P | 2 weeks | (1) |

| Chang, A. 2006 [48] | USA | Cross-over double blind | 16 | 16 |

Patients with normal glucose tolerance Age 70 ± 6 BMI 26 ± 3 |

NA 2000 mg/d | P | 2 weeks | (1) |

| Chang, A. 2006 [48] | USA | Cross-over double blind | 14 | 14 |

Patients with impaired glucose tolerance Age 70 ± 6 BMI 25 ± 3 |

NA 2000 mg/d | P | 2 weeks | (4) |

| Benjó, A. 2006 [49] | Brazil | Parallel double blind | 11 | 11 |

Patients with low HDL-cholesterol BMI (T/C) 27.4 ± 3.7/26.5 ± 3.7 |

no-flush niacin 1500 mg/d | P | 3 months | (1) |

| Taylor, A. 2004 [50] | USA | Parallel double blind | 78 | 71 | Age (T/C) 67 ± 10/68 ± 10 | ERN 1000 mg/d | P | 12 months | (6) |

| Osar, Z. 2004 [51] | Turkey | Parallel | 15 | 15 |

Age (T/C) 55 ± 10/59 ± 8 BMI (T/C) 30 ± 5/28 ± 3 |

NAM 50 mg/kg | P | 1 month | (4) |

| Superko, H. 2004 [52] | USA | Parallel | 60 | 61 |

Age (T/C) 53 ± 12/55 ± 12 BMI (T/C) 29 ± 4.4/27 ± 3.6 |

ERN 1500 mg/d | P | 14 weeks | (3) |

| Superko, H. . 2004 [52] | USA | Parallel | 59 | 61 |

Age (T/C) 53 ± 11/55 ± 12 BMI (T/C) 28 ± 5.2/27 ± 3.6 |

IRN 3000 mg/d | P | 14 weeks | (3) |

| Elam, M. 2000 [53] | USA | Parallel double blind | 49 | 50 |

Patients with diabetes Age 67 ± 7 BMI 28 ± 5 |

Niacin 3000 mg/d or maximum tolerated dosage | P | 18 weeks | (4) |

| Elam, M. 2000 [53] | USA | Parallel double blind | 145 | 150 |

Patients without diabetes Age 65 ± 9 BMI 27 ± 5 |

Niacin 3000 mg/d or maximum tolerated dosage | P | 18 weeks | (1) |

| Keenan, J. 1992 [54] | USA | Parallel double blind | 21 | 26 | Age (Mean) 58.7 | NA 2000–1500 mg/d | P | 24 weeks | (3) |

| Keenan, J. . 1992 [54] | USA | Parallel double blind | 26 | 12 | Age (Mean) 39.9 | NA 2000–1500 mg/d | P | 24 weeks | (3) |

| Garg, A. 1990 [55] | USA | Cross-over | 13 | 13 |

Age 59 ± 1 BMI 29.9 ± 0.7 |

NA 4500 mg/d | no therapy | 8 weeks | (4) |

| Chase, H. 1990 [56] | USA | Parallel double blind | 18 | 17 | Age (T/C) 12.5 ± 3.7/10.8 ± 3.5 | slow release NAM (100 mg.age (years)−1.day−1 up to a maximum of 1.5 g/day) | P | 12 months | (4) |

| Vague, P. 1989 [57] | France | Parallel double blind | 11 | 12 | Age (T/C) 29.8 ± 7.3/26.8 ± 6.2 | NAM 3000 mg/d | P | 9 months | (4) |

ERN: extended-release nicotinic acid; IRN: immediate-release niacin; P: Placebo; NRPT: Nicotinamide riboside + pterostilbene; P-OM3: Prescription omega-3 acid ethyl esters; ω-3 FA: ω-3 fatty acids; -: Not reported;

(1) Healthy people; (2) Chronic kidney disease (CKD); (3) Dyslipidemia; (4) Pathoglycemia; (5) Cardiovascular disease; (6) Other

Fig. 2.

Quality assessment chart

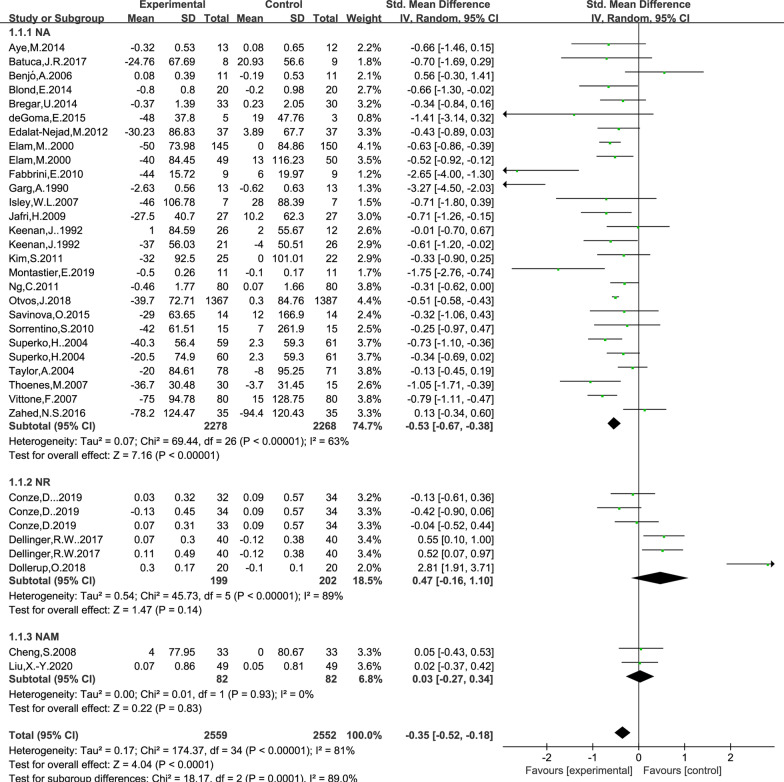

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on TG level

The data for determining the effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on TG level was available in 29 trials (NA24, NR3, NAM2), including 2559 cases in the drug group and 2552 cases in the control group. The random-effects model was used for analyses. The results of meta-analysis showed that: NAD+ precursor can significantly reduce TG level in the patients (SMD = − 0.35, 95% CI (− 0.52, − 0.18), P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). Subgroup analysis showed that there was statistically significant difference in supplemental NA (SMD = − 0.53, 95% CI (− 0.67, − 0.38), P < 0.00001; Fig. 3), while there was no statistically significant difference in supplemental NR and NAM (P = 0.14 and P = 0.83; Fig. 3). No significant publication bias was found in the results of Begg’s plots (P = 1.80 and Egger’s test (P = 0.058) for TG.

Fig. 3.

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on TG

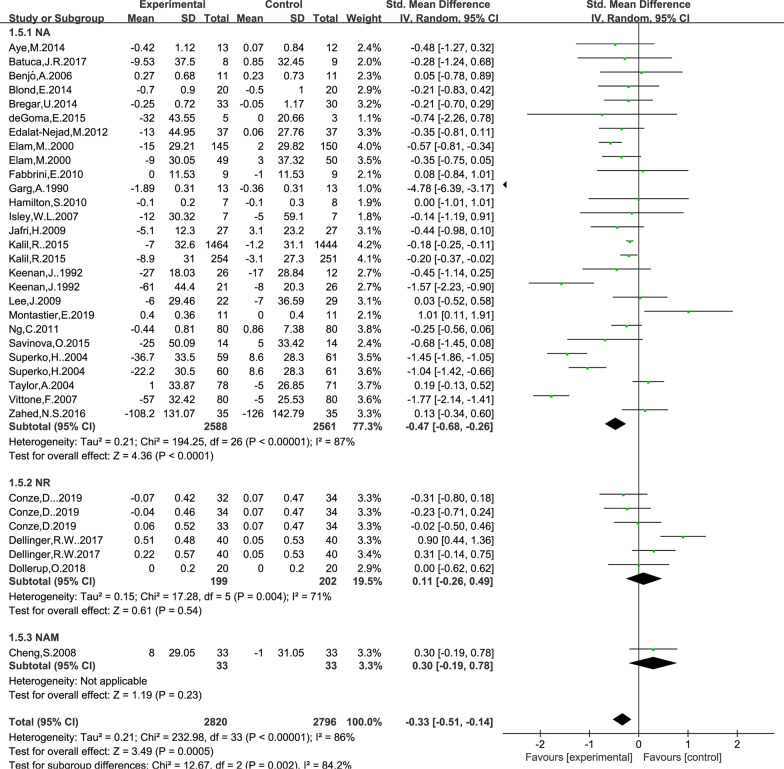

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on TC level

The data for determining the effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on TC level was available in 27 trials (NA23, NR3, NAM1), including 2820 cases in the drug group and 2796 cases in the control group. The random-effects model was used for analyses. The results of meta-analysis showed that: NAD+ precursor can significantly reduce TC level in the patients (SMD = − 0.33, 95% CI (− 0.51, − 0.14), P = 0.0005; Fig. 4). Subgroup analysis showed that there was statistically significant difference in supplemental NA (SMD = − 0.47, 95% CI (− 0.68, − 0.26), P < 0.0001; Fig. 4), while there was no statistically significant difference in supplemental NR and NAM (P = 0.54 and P = 0.23). No significant publication bias was found in Begg’s plots (P = 1.54) and Egger’s test (P = 0.16) for TC.

Fig. 4.

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on TC

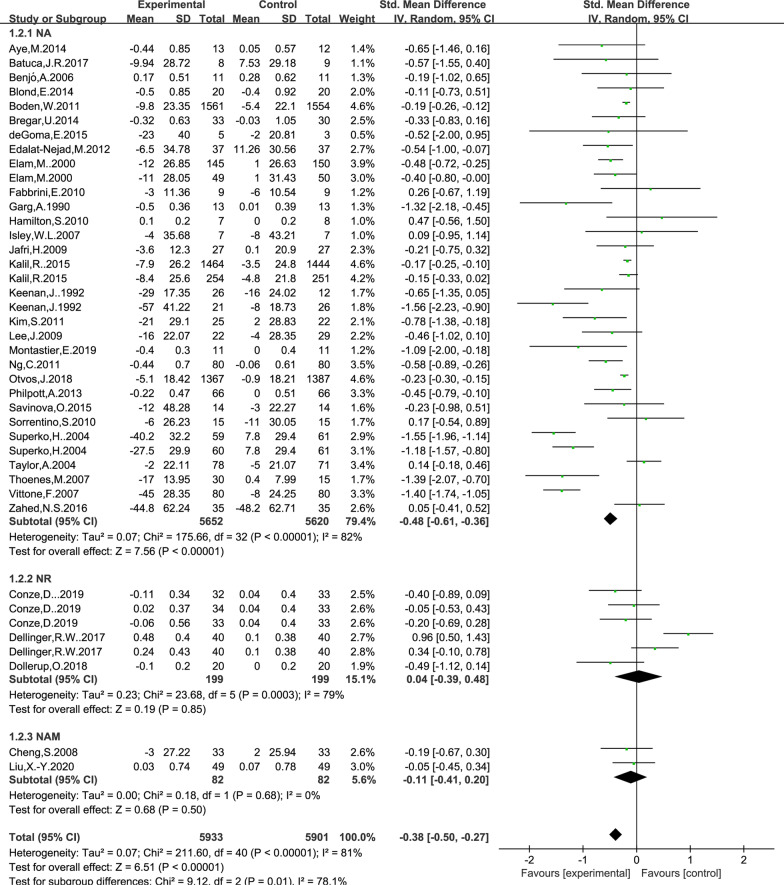

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on LDL level

The data for determining the effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on LDL level were available in 34 trials (NA29, NR3, NAM2), including 5933 cases in the drug group and 5901 cases in the control group. The random-effects model was used for analyses. The results of meta-analysis showed that: NAD+ precursor can significantly reduce LDL level in the patients (SMD = − 0.38, 95% CI (− 0.50, − 0.27), P < 0.00001; Fig. 5). Subgroup analysis showed that there was statistically significant difference in supplemental NA (SMD = − 0.48, 95% CI (− 0.61, − 0.36), P < 0.00001; Fig. 5), while there was no statistically significant difference in supplemental NR and NAM (P = 0.85 and P = 0.50). NO significant publication bias was found in Begg’s plots (P = 1.51) and Egger’s test (P = 0.64) for LDL level.

Fig. 5.

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on LDL

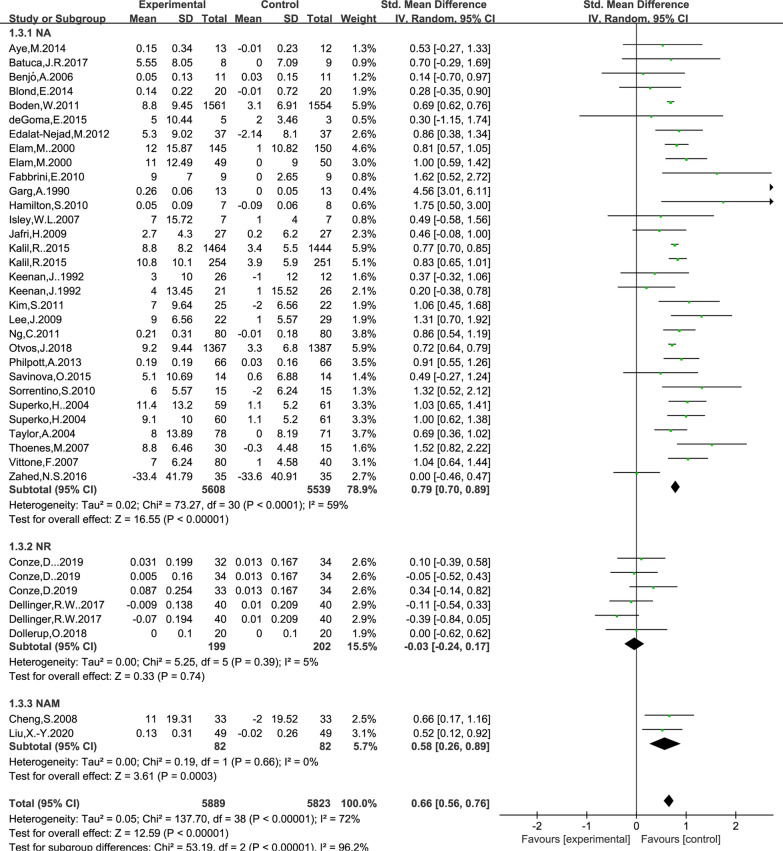

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on HDL level

The data for determining the effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on plasma glucose was available in 32 trials (NA27, NR3, NAM2), including 5889 cases in the drug group and 5823 cases in the control group. The random-effects model was used for analyses. The results of meta-analysis showed that: NAD+ precursor can significantly increase HDL level in the patients (SMD = 0.66, 95% CI (0.56, 0.76), P < 0.00001; Fig. 6). Subgroup analysis showed that there was statistically significant difference in supplemental NA and NAM (SMD = 0.79, 95% CI (0.70, 0.89), P < 0.00001; Fig. 6) and (SMD = 0.58, 95% CI (0.26, 0.89), P = 0.0003; Fig. 6), while there was no statistically significant difference in supplemental NR (P = 0.74). No significant publication bias was found in Begg’s plots (P = 0.66) and Egger’s test (P = 0.073) for HDL.

Fig. 6.

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on HDL

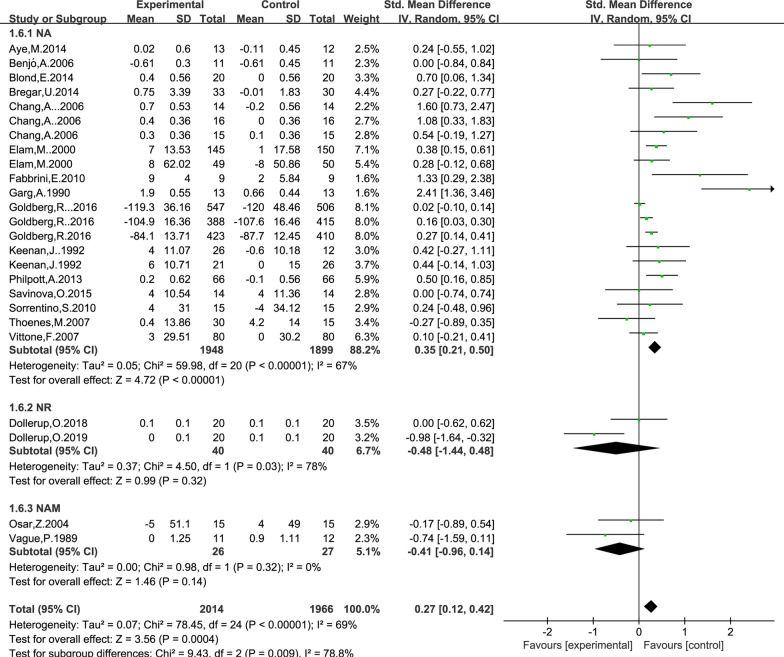

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on fasting plasma glucose level

The data for determining the effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on plasma glucose level was available in 19 trials (NA15, NR2, NAM2), including 2014 cases in the drug group and 1966 cases in the control group. The random-effects model was used for analyses. The results of meta-analysis showed that: NAD+ precursor can significantly increase plasma glucose level in the patients (SMD = 0.27, 95% CI (0.12, 0.42), P = 0.0004; Fig. 7). Subgroup analysis showed that there was statistically significant difference in supplemental NA (SMD = 0.35, 95% CI (0.21, 0.50), P < 0.00001; Fig. 6), while there was no statistically significant difference in supplemental NR and NAM (P = 0.32 and P = 0.14). No significant publication bias was found in Begg’s plots (P = 0.34) and Egger’s test (P = 0.18) for the plasma glucose level.

Fig. 7.

Effect of NAD+ precursor supplementation on Fasting plasma glucose

According to the different health status of patients to Subgroup analysis

To make the study comprehensive, we included all the data we could collect in the study. Due to the different health status of patients, we divided all patients into 6 groups for subgroup analysis. The results are shown in Table 2. These six groups are (1) healthy people: We default to healthy people without special instructions in the article. (2) Dyslipidemia: including abnormal levels of HDL, LDL, TC and TG; (3) Pathoglycemia: including impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus; (4) Cardiovascular diseases: including atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, old myocardial infarction, etc.; (5) Chronic kidney disease (CKD); (6) Others.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis

| Subgroup | TG | TC | LDL | HDL | Fasting plasma glucose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy people | SMD = 0.33, 95% CI = (− 0.23, 0.88), P = 0.25 | SMD = 0.00, 95% CI = (− 0.37, 0.38), P = 0.99 | SMD = − 0.06, 95% CI = (− 0.43, 0.32), P = 0.76 | SMD = 0.12, 95% CI = (− 0.24, 0.48), P = 0.51 | SMD = 0.33, 95% CI = (0.16, 0.50), P = 0.0001 |

| CKD | SMD = − 0.05, 95% CI = (− 0.30, 0.19), P = 0.66 | SMD = − 0.08, 95% CI = (− 0.33, 0.18), P = 0.56 | SMD = − 0.16, 95% CI = (− 0.30,− 0.02), P = 0.02 | SMD = 0.60, 95% CI = (0.31, 0.89), P < 0.0001 | - |

| Dyslipidemia | SMD = − 0.47, 95% CI = (− 0.63,− 0.31), P < 0.00001 | SMD = − 0.68, 95% CI = (− 1.07 ,− 0.29), P = 0.0006 | SMD = − 0.80, 95% CI = (− 1.18, − 0.41), P < 0.0001 | SMD = 0.79, 95% CI = (0.63, 0.96), P < 0.00001 | SMD = 0.27, 95% CI = (− 0.08, 0.61), P = 0.13 |

| Pathoglycemia | SMD = − 1.83, 95% CI = (− 4.52, 0.86), P = 0.18 | SMD = − 1.56, 95% CI = (− 3.61,− 0.49), P = 0.14 | SMD = − 0.45, 95% CI = (− 1.26, 0.36), P = 0.27 | SMD = 2.32, 95% CI = (0.44, 4.20), P = 0.02 | SMD = 0.31, 95% CI = (− 0.01, 0.63), P = 0.06 |

| Cardiovascular disease | SMD = − 0.52, 95% CI = (− 0.60,− 0.45), P < 0.00001 | SMD = − 0.69, 95% CI = (− 1.51, 0.13), P = 0.10 | SMD = − 0.48, 95% CI = (− 0.88,− 0.08), P = 0.02 | SMD = 0.73, 95% CI = (0.66, 0.80), P = < 0.00001 | SMD = 0.28, 95% CI = (0.03, 0.54), P = 0.03 |

| Other | SMD = − 0.92, 95% CI = (− 1.68,− 0.16), P = 0.02 | SMD = 0.14, 95% CI = (− 0.20, 0.49), P = 0.42 | SMD = − 0.18, 95% CI = (− 0.43, 0.07), P = 0.15 | SMD = 0.84, 95% CI = (0.59, 1.09), P = < 0.00001 | SMD = 0.15, 95% CI = (− 0.74, 1.04), P = 0.74 |

-: there is only one sample or no sample in the subgroup

It can be found that the supplement of NAD+ precursors seems to have little effect on healthy people, but it has a significant beneficial effect on patients with cardiovascular disease and dyslipidemia.

Discussion

In this study, a comprehensive meta-analysis of data from currently published clinical trials with NAD+ precursors showed that supplementation with NAD+ precursors improved the levels of TG, TC, LDL and HDL in humans compared with placebo or no treatment but resulted in high glucose levels. Among them, NA has the most significant effect on improving lipid metabolism. Currently, there is no meta-analysis on the effect of NAD+ precursors on lipid metabolism in the human body. Ding et al., performed a meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled trials showing that NA alone or in combination significantly improved dyslipidemia in patients with T2DM, but glucose levels need to be monitored during long-term treatment [12]. Xiang et al., conducted a meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials and found that NA supplementation can improve the level of blood lipid without affecting the level of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetic mellitus (T2DM) [13]. However, these studies were limited to patients with T2DM. This study was based on existing clinical RCTs to evaluate the effect of NAD+ supplementation on lipid control in humans. The comprehensive results showed that supplementation with NAD+ precursors significantly improved lipid metabolism in humans.

NA is widely used to regulate dyslipidemia and treat atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Studies have shown that niacin can reduce plasma TC, TG, and LDL levels, and increase HDL level. In addition, various clinical trials have shown that niacin therapy significantly reduces overall mortality from various cardiovascular diseases and delays the progression of atherosclerosis [14, 15]. Jin et al., used a human hepatoblastoma cell line (HepG2) model to study the relationship between NA and intracellular ApoB, and the results showed that NA significantly increased the degradation of intracellular ApoB [16]. NA inhibits the synthesis of TG through a variety of mechanisms, which may hinder the lipidation and transport of ApoB on the endoplasmic omentum, and may create a favorable environment for intracellular ApoB degradation. ApoB is the major protein of very low-density lipoproteins, intermediate-density lipoproteins, LDL and lipoprotein (a). These ApoB-containing lipoproteins (especially elevated LDL levels) are associated with accelerated atherosclerosis, and their decrease can delay the progression of atherosclerosis. It has been found that oral administration of 200 mg of NA daily can reduce plasma free fatty acid (FFA) concentration [17]. NA may inhibit the mobilization of adipose tissue by inhibiting the activity of triacylglycerase in adipose tissue, and reduce the release of free fatty acids in adipose cells, leading to a decrease in plasma FFA concentration and liver uptake of FFA, resulting in a decrease in TG synthesis and LDL secretion. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT2) is the key enzyme in TG synthesis, and NA can directly inhibit the activity of liver DGAT2, but has no effect on DGAT1 [18]. Hu et al., treated 39 patients with dyslipidemia with 2 g of ERN per day, and the results showed that plasma TG and liver fat contents decreased significantly, which was speculated to be caused by NA inhibiting hepatic DGAT2 [19]. However, it is worth noting that NA can lower blood lipids and is used to treat dyslipidemia, but at doses greater than 50 mg/day, NA can also cause flushing [20].

Nicotinamide riboside is a vitamin that occurs naturally in the human diet and is one of the precursors of NAD+ . In animal models, NR supplementation can improve glucose tolerance and reduce metabolic abnormalities in mice [21]. The study from Conze et al., showed that NR supplementation can improve the level of human lipid metabolism [1], which plays a role by activating sirtuins to regulate human metabolism. In rodents, NR is more efficient in boosting NAD+ than NA and NAM [22], but the number of clinical studies on NR intervention is relatively low, and the evidence of NR's benefit to human beings is limited.

Both NAM and NA are the main forms of vitamin B3 and, despite their similar structure, do not have the same effects. Currently, NAM is a commonly used treatment of dialysis patients with renal insufficiency to improve hyperphosphatemia in clinical. In previous reports, nicotinamide has no significant effect on human lipid metabolism [7], but in recent years, more and more studies have shown that nicotinamide can significantly improve the level of lipid metabolism in patients. Liu, X.Y. et al. studied 98 hemodialysis patients treated with NAM 500–1500 mg daily, and the results showed that after 52 weeks of intervention, the blood lipid level of the patients was significantly improved compared with placebo, and the blood glucose was not increased [9]. Cheng, et al. treated 33 patients with long-term hemodialysis with NAM 500–1500 mg daily, and after 8 weeks, the blood phosphorus level of the patients decreased significantly and the blood lipid level improved significantly [10]. The study of Takahashi et al., also showed that NAM treatment could improve patients' lipid metabolism [11]. At present, the number of studies on the improvement of human lipid metabolism by nicotinamide intervention is limited, and the mechanism remains unclear, but the existing studies have shown its great clinical value.

We divided all patients into 6 groups for subgroup analysis. It was found that the supplement of NAD+ precursors seems to have little effect on healthy people, but it has a significant beneficial effect on patients with cardiovascular disease and dyslipidemia. Limitations of this study include the variation in study design, in the selection of inclusion articles, and reporting of the biochemical parameter. (1) In terms of study design, there were varying doses of the study medication, and some of the trials enforced strict diet and exercise regimens in addition to NAD+ precursor supplementation, or took simvastatin and Ezetimibe to background treatment, while others only supplemented NAD and did not incorporate any lifestyle modification into the design. In addition, inclusion criteria varied with some trials allowing diabetics, while others excluding such patients. (2) This study only includes English literature, which may affect the inference of results; The sample size included in the study varies greatly, which may lead to some heterogeneity. (3) In the report of biochemical parameters, some studies use mg/dl as the unit and some use μmol/L, which makes it difficult to collect data. Due to the limited number of published studies, the heterogeneity of efficacy of different precursors is greatly affected by study samples, and needs to be verified by more high-quality studies.

Conclusion

In this study, a meta-analysis based on currently published clinical trials with NAD+ precursors showed that supplementation with NAD+ precursors improved TG, TC, LDL, and HDL levels in humans, but resulted in hyperglycemia, compared with placebo or no treatment. Among them, NA has the most significant effect on improving lipid metabolism. In addition, although NR and NAM supplementation had no significant effect on improving human lipid metabolism, the role of NR and NAM could not be directly denied due to the few relevant studies at present. Based on subgroup analysis, we found that the supplement of NAD+ precursors seems to have little effect on healthy people, but it has a significant beneficial effect on patients with cardiovascular disease and dyslipidemia. Due to the limitation of the number and quality of included studies, the above conclusions need to be verified by more high-quality studies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Search strategy for the meta-analysis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- DGAT2

Diacylglycerol acyltransferase

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- NA

Nicotinic Acid

- NAM

Nicotinamide

- NMN

Nicotinamide Mononucleotide

- NR

Nicotinamide Riboside

- QA

Quinolinic acid

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- SMD

Standardized Mean Difference

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetic mellitus

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

Authors' contributions

OZ, JW, XL and ZT conceived the research, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. JW and YT performed the data collection and statistical analysis. All the authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (No. 82101720); Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2020JJ5500); Key Lab for Clinical Anatomy & Reproductive Medicine of Hengyang City (2017KJ182), Hunan Provincial Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (No. X202110555538).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ou Zhong and Jinyuan Wang have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Ou Zhong, Email: 2897169255@qq.com.

Jinyuan Wang, Email: 932510486@qq.com.

Yongpeng Tan, Email: tanyongpeng425@163.com.

Xiaocan Lei, Email: 2019000013@usc.edu.cn.

Zhihan Tang, Email: 9906430@qq.com.

References

- 1.Conze D, Brenner C, Kruger C. Safety and metabolism of long-term administration of NIAGEN (Nicotinamide Riboside Chloride) in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of healthy overweight adults. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9772. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46120-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogan KL, Brenner C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:115–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajman L, Chwalek K, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic potential of NAD-boosting molecules: the in vivo evidence. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):529–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frye RA. Characterization of five human cDNAs with homology to the yeast SIR2 gene: Sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) metabolize NAD and may have protein ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260(1):273–279. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belenky P, Bogan KL, Brenner C. NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuang J, Chen L, Tang Q, Zhang J, Li Y, He J. The role of Sirt6 in obesity and diabetes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:135. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altschul R, Hoffer A, Stephen JD. Influence of nicotinic acid on serum cholesterol in man. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1955;54(2):558–559. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(55)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellinger RW, Santos SR, Morris M, Evans M, Alminana D, Guarente L, Marcotulli E. Repeat dose NRPT (nicotinamide riboside and pterostilbene) increases NAD (+) levels in humans safely and sustainably: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2017;3:17. doi: 10.1038/s41514-017-0016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X-Y, Yao J-R, Xu R, Xu L-X, Zhang Y-F, Lu S, Xing Z-H, Fan L-P, Qin Z-H, Sun B. Investigation of nicotinamide as more than an anti-phosphorus drug in chronic hemodialysis patients: a single-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:530. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S, Young D, Huang Y, Delmez J, Coyne D. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of niacinamide for reduction of phosphorus in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1131–1138. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04211007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi Y, Tanaka A, Nakamura T, Fukuwatari T, Shibata K, Shimada N, Ebihara I, Koide H. Nicotinamide suppresses hyperphosphatemia in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2004;65(3):1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding Y, Li YW, Wen AD. Effect of niacin on lipids and glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(5):838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiang D, Zhang Q, Wang YT. Effectiveness of niacin supplementation for patients with type 2 diabetes. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2020;99(29):e21235. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canner P, Berge K, Wenger N, Stamler J, Friedman L, Prineas R, Friedewald W. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blankenhorn D, Nessim S, Johnson R, Sanmarco M, Azen S, Cashin-Hemphill L. Beneficial effects of combined colestipol-niacin therapy on coronary atherosclerosis and coronary venous bypass grafts. JAMA. 1987;257:3233–3240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin FY, Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Niacin accelerates intracellular ApoB degradation by inhibiting triacylglycerol synthesis in human hepatoblastoma (HepG2) cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(4):1051–1059. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson LA. Nicotinic acid: the broad-spectrum lipid drug. A 50th anniversary review. J Intern Med. 2005;258(2):94–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganji SH, Tavintharan S, Zhu D, Xing Y, Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Niacin noncompetitively inhibits DGAT2 but not DGAT1 activity in HepG2 cells. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(10):1835–1845. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300403-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu M, Chu WC, Yamashita S, Yeung DK, Shi L, Wang D, Masuda D, Yang Y, Tomlinson B. Liver fat reduction with niacin is influenced by DGAT-2 polymorphisms in hypertriglyceridemic patients. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(4):802–809. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P023614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyton JR, Bays HE. Safety considerations with niacin therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(6a):22c–31c. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dollerup O, Trammell S, Hartmann B, Holst J, Christensen B, Møller N, Gillum M, Treebak J, Jessen N. Effects of nicotinamide riboside on endocrine pancreatic function and incretin hormones in nondiabetic men with obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:5703–5714. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-01081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trammell SA, Schmidt MS, Weidemann BJ, Redpath P, Jaksch F, Dellinger RW, Li Z, Abel ED, Migaud ME, Brenner C. Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12948. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montastier E, Beuzelin D, Martins F, Mir L, Marqués M, Thalamas C, Iacovoni J, Langin D, Viguerie N. Niacin induces miR-502-3p expression which impairs insulin sensitivity in human adipocytes. Int J Obes (2005) 2019;43:1485–1490. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dollerup O, Christensen B, Svart M, Schmidt M, Sulek K, Ringgaard S, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, Møller N, Brenner C, Treebak J, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of nicotinamide riboside in obese men: safety, insulin-sensitivity, and lipid-mobilizing effects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:343–353. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otvos J, Guyton J, Connelly M, Akapame S, Bittner V, Kopecky S, Lacy M, Marcovina S, Muhlestein J, Boden W. Relations of GlycA and lipoprotein particle subspecies with cardiovascular events and mortality: a post hoc analysis of the AIM-HIGH trial. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12:348‐355.e342. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batuca JR, Amaral MC, Favas C, Paula FS, Ames PRJ, Papoila AL, Alves JD. Extended-release niacin increases antiapolipoprotein A-I antibodies that block the antioxidant effect of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol: the EXPLORE clinical trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(5):1002–1010. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg R, Bittner V, Dunbar R, Fleg J, Grunberger G, Guyton J, Leiter L, McBride R, Robinson J, Simmons D, et al. Effects of extended-release niacin added to simvastatin/ezetimibe on glucose and insulin values in AIM-HIGH. Am J Med. 2016;129:753.e713‐722. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zahed NS, Zamanifar N, Nikbakht H. Effect of low dose nicotinic acid on hyperphosphatemia in patients with end stage renal disease. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26(4):239–243. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.161020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savinova O, Fillaus K, Harris W, Shearer G. Effects of niacin and omega-3 fatty acids on the apolipoproteins in overweight patients with elevated triglycerides and reduced HDL cholesterol. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.04.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalil RS, Wang JH, De Boer IH, Mathew RO, Ix JH, Asif A, Shi X, Boden WE. Effect of extended-release niacin on cardiovascular events and kidney function in chronic kidney disease: a post hoc analysis of the AIM-HIGH trial. Kidney Int. 2015;87:1250–1257. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.deGoma E, Salavati A, Shinohara R, Saboury B, Pollan L, Schoen M, Torigian D, Mohler E, Dunbar R, Litt H, et al. A pilot trial to examine the effect of high-dose niacin on arterial wall inflammation using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Acad Radiol. 2015;22:600–609. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bregar U, Jug B, Keber I, Cevc M, Sebestjen M. Extended-release niacin/laropiprant improves endothelial function in patients after myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels. 2014;29:313–319. doi: 10.1007/s00380-013-0367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blond E, Rieusset J, Alligier M, Lambert-Porcheron S, Bendridi N, Gabert L, Chetiveaux M, Debard C, Chauvin M, Normand S, et al. Nicotinic acid effects on insulin sensitivity and hepatic lipid metabolism: an in vivo to in vitro study. Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung / Hormones et metabolisme [Hormone Metab Res] 2014;46:390–396. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aye M, Kilpatrick E, Afolabi P, Wootton S, Rigby A, Coady A, Sandeman D, Atkin S. Postprandial effects of long-term niacin/laropiprant use on glucose and lipid metabolism and on cardiovascular risk in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:545–552. doi: 10.1111/dom.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philpott A, Hubacek J, Sun Y, Hillard D, Anderson T. Niacin improves lipid profile but not endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease on high dose statin therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edalat-Nejad M, Zameni F, Talaiei A. The effect of niacin on serum phosphorus levels in dialysis patients. Indian J Nephrol. 2012;22:174–178. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.98751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng C, Lee C, Ho A, Lee V. Effect of niacin on erectile function in men suffering erectile dysfunction and dyslipidemia. J Sex Med. 2011;8:2883–2893. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, Kim M, Lee H, Kang H, Kim Y, Park B, Kim H. Efficacy and tolerability of a new extended-release formulation of nicotinic acid in Korean adults with mixed dyslipidemia: an 8-week, multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2011;33:1357–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boden W, Probstfield J, Anderson T, Chaitman B, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fabbrini E, Mohammed B, Korenblat K, Magkos F, McCrea J, Patterson B, Klein S. Effect of fenofibrate and niacin on intrahepatic triglyceride content, very low-density lipoprotein kinetics, and insulin action in obese subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2727–2735. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sorrentino S, Besler C, Rohrer L, Meyer M, Heinrich K, Bahlmann F, Mueller M, Horváth T, Doerries C, Heinemann M, et al. Endothelial-vasoprotective effects of high-density lipoprotein are impaired in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus but are improved after extended-release niacin therapy. Circulation. 2010;121:110–122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.836346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamilton S, Chew G, Davis T, Watts G. Niacin improves small artery vasodilatory function and compliance in statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2010;7:296–299. doi: 10.1177/1479164110376206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J, Robson M, Yu L, Shirodaria C, Cunnington C, Kylintireas I, Digby J, Bannister T, Handa A, Wiesmann F, et al. Effects of high-dose modified-release nicotinic acid on atherosclerosis and vascular function: a randomized, placebo-controlled, magnetic resonance imaging study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1787–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jafri H, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Mooney P, Kimmelstiel CD, Karas RH, Kuvin JT. Extended-release niacin reduces LDL particle number without changing total LDL cholesterol in patients with stable CAD. J Clin Lipidol. 2009;3(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vittone F, Chait A, Morse JS, Fish B, Brown BG, Zhao XQ. Niacin plus simvastatin reduces coronary stenosis progression among patients with metabolic syndrome despite a modest increase in insulin resistance: a subgroup analysis of the HDL-Atherosclerosis Treatment Study (HATS) J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1(3):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thoenes M, Oguchi A, Nagamia S, Vaccari C, Hammoud R, Umpierrez G, Khan B. The effects of extended-release niacin on carotid intimal media thickness, endothelial function and inflammatory markers in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:1942–1948. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Isley WL, Miles JM, Harris WS. Pilot study of combined therapy with ω-3 fatty acids and niacin in atherogenic dyslipidemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang A, Smith M, Galecki A, Bloem C, Halter J. Impaired beta-cell function in human aging: response to nicotinic acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3303–3309. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benjó A, Maranhão R, Coimbra S, Andrade A, Favarato D, Molina M, Brandizzi L, da Luz PL. Accumulation of chylomicron remnants and impaired vascular reactivity occur in subjects with isolated low HDL cholesterol: effects of niacin treatment. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor A, Sullenberger L, Lee H, Lee J, Grace K. Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol (ARBITER) 2: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of extended-release niacin on atherosclerosis progression in secondary prevention patients treated with statins. Circulation. 2004;110:3512–3517. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148955.19792.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osar Z, Samanci T, Demirel G, Damci T, Ilkova H. Nicotinamide effects oxidative burst activity of neutrophils in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Diabesity Res. 2004;5:155–162. doi: 10.1080/15438600490424244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Superko H, McGovern M, Raul E, Garrett B. Differential effect of two nicotinic acid preparations on low-density lipoprotein subclass distribution in patients classified as low-density lipoprotein pattern A, B, or I. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elam M, Hunninghake D, Davis K, Garg R, Johnson C, Egan D, Kostis J, Sheps D, Brinton E. Effect of niacin on lipid and lipoprotein levels and glycemic control in patients with diabetes and peripheral arterial disease: the ADMIT study: a randomized trial. Arterial Disease Multiple Intervention Trial. JAMA. 2000;284:1263–1270. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keenan J, Bae C, Fontaine P, Wenz J, Myers S, Huang Z, Ripsin C. Treatment of hypercholesterolemia: comparison of younger versus older patients using wax-matrix sustained-release niacin. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garg A, Grundy S. Nicotinic acid as therapy for dyslipidemia in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1990;264:723–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chase H, Butler-Simon N, Garg S, McDuffie M, Hoops S, O'Brien D. A trial of nicotinamide in newly diagnosed patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1990;33:444–446. doi: 10.1007/BF00404097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vague P, Picq R, Bernal M, Lassmann-Vague V, Vialettes B. Effect of nicotinamide treatment on the residual insulin secretion in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 1989;32:316–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00265549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Search strategy for the meta-analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.