Abstract

Objectives

Explore the views of two main stakeholders: mental health professionals and volunteers from three European countries, on the provision of volunteering in mental healthcare.

Design

A multicountry, multilingual and multicultural qualitative focus group study (n=24) with n=119 participants.

Participants

Volunteers and mental health professionals in three European countries (Belgium, Portugal and the UK).

Results

Mental health professionals and volunteers consider it beneficial offering volunteering to their patients. In this study, six overarching themes arose: (1) there is a framework in which volunteering is organised, (2) the role of the volunteer is multifaceted, (3) every volunteering relationship has a different character, (4) to volunteer is to face challenges, (5) technology has potential in volunteering and (6) volunteering impacts us all. The variability of their views suggests a need for flexibility and innovation in the design and models of the programmes offered.

Conclusions

Volunteering is not one single entity and is strongly connected to the cultural context and the mental healthcare services organisation. Despite the contextual differences between these three European countries, this study found extensive commonalities in attitudes towards volunteering in mental health.

Keywords: volunteering, mental health, stakeholders, Europe, International Qualitative Research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This has been the first multiperspective study to explore the views of mental healthcare professionals and volunteers regarding the provision of volunteering in mental healthcare across European countries in different regions with varied sociocultural contexts.

This international study was conducted by a multicountry collaborative multidisciplinary team, with a background in psychiatry and psychology, and with and without experience in volunteering in mental health.

The methodology used was consistent across countries in terms of recruitment and acknowledgement of participation, and all the data were analysed in the original languages.

Introduction

Within different countries, volunteering may exist to varying degrees. It may have diverse purposes and structures, aiming to provide different types of relationships from friendships to more professional therapeutic interactions.1 Across the world there are different paradigms underlying volunteering.2 3 The non-profit paradigm is the dominant view in the UK and other Western high-income societies, while the civil society paradigm is the common lens through which volunteering is seen in southern low-and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 Previous research has sought to comprehend the common core principles in the general public’s understanding of volunteering across countries.4–6 Research conducted in eight countries on the public perception of volunteering showed that there was a general consensus concerning the definition of what constitutes a volunteer.7 The three main defining principles that form the essence of volunteering are: absence of remuneration, free will and benefit to others.5 8

In mental health, two stakeholders who are key in the provision of volunteering support are the mental health professionals and the volunteers themselves. The former can encourage participation or even prescribe these initiatives to their patients, whereas the latter constitute the ‘active ingredients’ of volunteering, offering their free time to support and maintain contact with patients. Volunteers’ roles seem to vary and their individual characteristics may be linked to cultural, religious and social context. Therefore, differences within communities and countries may affect volunteer–patient relationships and impact how volunteering is perceived and provided. Usually, these volunteer–patient interactions take place in person, but some communities and countries may face barriers to establishing face-to-face encounters. The majority of the research conducted has either evaluated public perceptions of volunteering or described the actual characteristics of volunteers; there is a dearth of information regarding mental health professionals’ and volunteers’ views, which are valuable.

In Europe, even though countries have been closely connected through the European Union, the landscape of volunteering in mental health varies across nations.9 In the UK there are more than 3 million volunteers,10 11 representing a vital resource for communities12 with several volunteering programmes offered mostly by the third sector.13 In Belgium, the opportunities available seem to have close links with healthcare structures,14 15 whereas in Portugal volunteering in mental health barely exists.16 17 The existing differences may reflect wider societal diversity, and mental health services structure. The UK, an island lying off the North Western coast, is influenced by Anglican values and London is shaped by a multicultural ambience; Belgium, positioned in Central Europe is the heart of many European institutions, its nationals are multilingual, with most of the population speaking both French and Dutch; whereas Portugal, located in Southern Europe, holds Catholic and Mediterranean cultural roots. These socio-geographical diverse countries spanning the North, Central and South Europe were chosen for this international focus group study because of their dissimilar traditions of volunteering in mental health.

The objectives of this study were to explore the views of mental health professionals and volunteers from three European countries on: the purpose, benefits and challenges of volunteering in mental health; the character of these one-to-one relationships; and the formats in which these contacts should be made.

Methods

Study design

This was an international cross-cultural, multilingual focus group study. As described elsewhere, this qualitative study was conducted in two stages, that is, a pilot phase and the main study.18

Research team

The research team for the main study consisted of the lead author and three other researchers described in detail in table 1. Each of the researchers in the team co-facilitated the focus groups alongside the lead author and subsequently, supported with data analysis. This second researcher (ST in London, MC in Brussels and FMdS in Porto) also provided support in the interpretation of data context specificity.

Table 1.

Research team and characteristics

| Researcher 1 | Researcher 2 | Researcher 3 | Researcher 4 | |

| Site(s) | Pilot, London, Brussels, Porto | London | Brussels | Porto |

| Gender, professional role and credentials | Female, psychiatrist, MSc Mental Health Policies and Services, cognitive behavioural therapy training, social psychiatry researcher. |

Female, BSc, MSc, social psychiatry researcher. |

Female, BA, MSc, social psychiatry researcher. |

Male, psychiatry trainee, interpersonal psychotherapy training. |

| Role in the research | Facilitator, lead analyst. |

Co-facilitator, support data analysis. |

Co-facilitator, support data analysis. |

Co-facilitator, support data analysis. |

| Experience with the local context | Born in Portugal and lived in Porto for 25 years, lived in Italy for 1 year, lived in Poland for 1 year, lived in the UK for 5 years. Involved in international work through leading professional organisations and conducting international research studies. |

Born in UK and lived in London for 2 years. | Born in Belgium and lived in Brussels for 18 years. | Born in Portugal and lived in Porto for 30 years. |

| Experience in volunteering (and in mental health) | Yes (yes) | Yes (yes) | Yes (yes) | Yes (no) |

The lead author had established a relationship prior to study commencement with all the members of the research team. All of them were aware of the context of this study, and all were trained in the conduct of focus groups and qualitative analysis.

Recruitment

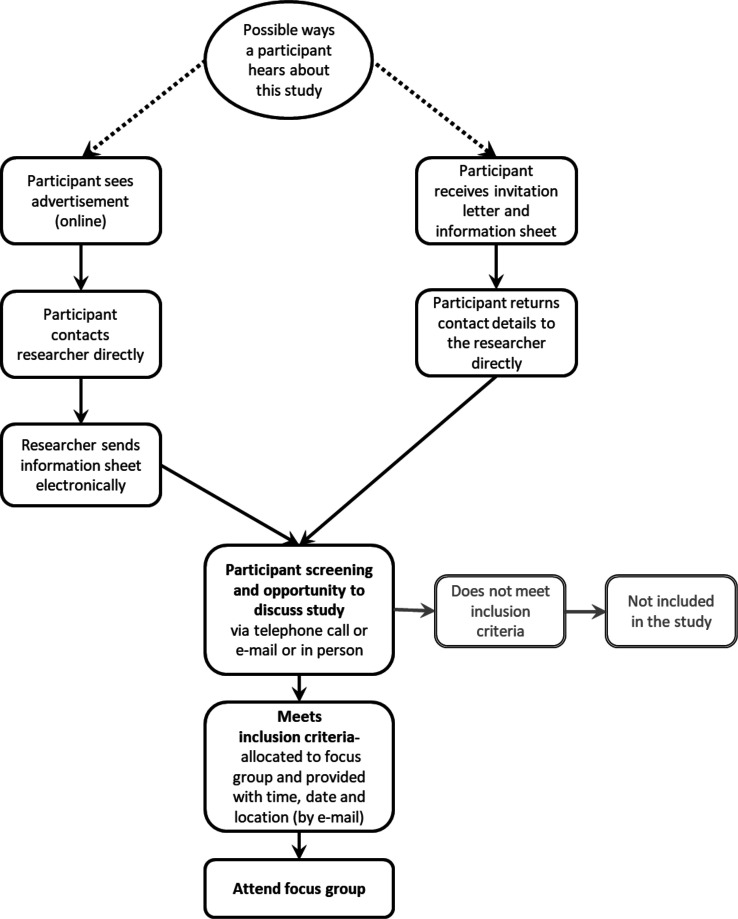

Figure 1 summarises recruitment for this study.

Figure 1.

Study scheme diagram

For the pilot stage, international mental health researchers and psychiatrists were recruited. Researchers working at the Unit for Social and Community Psychiatry (USCP), a WHO Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Services Development were invited to take part. Additionally, psychiatrists from various European countries that attended the 24th European Congress of Psychiatry in Madrid, Spain, were offered the opportunity to participate.

For the main study, mental health professionals and volunteers were recruited from three European countries. In London, an email with information about the study was sent to mental health staff working at the East London NHS Foundation Trust (ELFT) which is a Mental Health Trust; in Brussels, the invitation was sent to clinicians via local contacts from the Université Catholique de Louvain (UCL); in Porto this information was sent to the mental health staff working at Hospital de Magalhães Lemos, a psychiatric hospital. Volunteers were recruited from healthcare organisations, non-governmental organisations or volunteering and community associations. In addition, planned snowball sampling was used while inviting potential participants to share the invitation with their contacts. An email with information about the study was sent to volunteering organisations in the UK, Portugal and Belgium. These volunteering organisations then disseminated information about the study through their networks, via email, websites or social media.

Eligibility criteria

People with a qualification in one or more of the following mental health professions: psychiatry, psychology, nursing, occupational therapy or social work, and working in a mental health service were deemed eligible to take part in the mental health professionals' focus groups. People aged 18 years or over, experience in volunteering and capacity to provide informed consent were deemed eligible for the volunteers focus groups.

Participant identification and consent

Potential participants received an invitation letter and information sheet about the study by email. Via email, phone or in person, the lead author discussed the study details with the potential participants, checked the inclusion criteria were met and discussed practical information about location and times, to be confirmed in writing. On the day of the focus group, informed consent was obtained from participants. They were also asked to complete a brief questionnaire regarding their socio-demographic characteristics.

Sampling considerations

Separate focus groups for mental health professionals and volunteers were hosted in order to ensure equal voices and sufficient homogeneity of the group composition. This aimed to encourage participants to express their views freely, and avoid group dynamics which could inhibit an open discussion.

In this study, a minimum of two and a maximum of four focus groups per country would be conducted to provide enough coverage of the topics, and to ensure that all areas could be explored in detail. Focus groups were planned with between four to eight participants. This was deemed a manageable number of people to enable a group discussion and to capture a range of views from individuals from different backgrounds, while providing sufficient data to gain an understanding of the experiences and views of mental health professionals and volunteers on volunteering in mental health.

Procedures

First, the views of international mental health researchers and psychiatrists from different European countries were sought in order to understand and to scope out the diversity of viewpoints and to allow refinements in the topic guide. Once the pilot stage was complete, this methodology was applied in three European countries. This facilitated a comparison of potential similarities and differences across the two stakeholder groups and three sites, that is, London, Brussels and Porto.

Instruments

The study documents, that is, protocol, topic guide, information sheet, consent form and participants’ socio-demographic characteristics questionnaire were developed in English, and then translated into Portuguese and French, languages in which the lead author is fluent. The versions of the instruments in the three languages were checked by another native speaker in the three sites (ST for English, MC for French and FMdS for Portuguese).

Structure of the focus groups and their facilitation

All focus groups followed the topic guide and lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Focus groups were conducted in one of the national languages of the hosting city, that is, English, French or Portuguese. The lead author and the co-facilitator (ST in London, MC in Brussels and FMdS in Porto) debriefed at the end of each session, and discussed key topics.

Setting

The focus groups were scheduled for varied times, including evenings, to maximise attendance and to allow people with different schedules and availabilities to take part if interested. Choosing a location was an important factor when planning the focus groups, to provide a safe and quiet space, ease of access and comfort. The pilot focus groups with international psychiatrists took place in a large room at the conference venue in Madrid, Spain. In London, the focus groups with international mental health researchers, mental health professionals and volunteers all took place in large meeting rooms at the USCP, located at the Newham Centre for Mental Health or in smaller meeting rooms at the Community Mental Health Teams’ premises; all locations were part of ELFT. In Porto, the meeting site with the mental health professionals was the Hospital de Magalhães Lemos, whereas the focus groups with volunteers took place at the University of Porto. In Belgium, all the groups were held at UCL in Brussels. All selected locations were serviced by good transport links and with parking spaces available nearby.

Data recording, transcription and analysis

The focus groups were audio recorded and then transcribed verbatim in the original languages by a professional transcription company. Participant-identifiable data were removed. Thematic analysis19 was conducted in the original language of each session using NVivo qualitative analysis software, V.11. In addition to the lead author, the second researcher at each site who was fluent in the original language, coded transcripts line-by-line and contributed to the development of the themes.

A recursive, that is, non-linear approach was used comprising the following stages19: familiarisation; coding; searching themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes and write up. It was ensured that the extracts used supported the analytical claims. The thematic analysis was primarily inductive given that the research team started this exploratory study with no predetermined theory, structure or framework on which to base data analysis.

The research team analysed the transcripts for themes that reflected the content of the text and subsequently, related themes were clustered together. This process was repeated several times, ensuring that no theme was over-represented or under-represented. Any disagreements were discussed iteratively until a decision was reached. Eventually, each group of themes was given an appropriate label, reflecting its content. Each group label was referred to as ‘main theme’ and its components were denoted as ‘subthemes’.

Once the lead author and the second researcher (ST in London, MC in Brussels and FMdS in Porto) had performed the first data analysis on all focus groups, the lead author repeated the process of searching for themes, which involved recoding. This process was done separately for every country and for each stakeholder group. The clusters of codes and themes were then presented to the wider research team. This process enabled the coherence of themes to be confirmed and provided an opportunity to explore the opinions of all members of the research team. The lead author then grouped the initially independent analysis and reported the findings by sites, that is, Brussels, London and Porto. The themes that are presented in the tables are a synthesis of the six analyses that were conducted, that is, two per country and each stakeholder that was involved in the main phase of this study. The analysis of the initial focus groups conducted in the pilot phase with international mental health researchers and psychiatrists informed the topic guides and procedures of the main study only and therefore are not reported further in this article. This article includes a selection of participants’ quotes in English translated by the lead author; the detailed analysis with participants’ quotes in tables in the original languages (Portuguese and French) is available in the online supplemental appendix 1. This article follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines to structure the study reporting.20 The authors acknowledge the potential impact of their own characteristics at the time of the study in the reflexivity of the research process (table 1).

bmjopen-2021-052185supp001.pdf (456.6KB, pdf)

Robustness assessment of the synthesis

To ensure external validity, the preliminary findings were presented to an audience of clinicians at the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) Congress and to volunteers at the Befriending Networks Congress. This ‘member checking’21 aimed to ensure that a range of viewpoints from clinicians and volunteers were taken into consideration, minimising bias in the interpretation of results. No specific suggestions for changes were made at these events.

Patient and public involvement

Volunteer associations and mental health professional associations were involved in the recruitment and the dissemination of this focus groups study. Patients were not involved in the recruitment of this focus group study.

Results

Twenty-four focus groups were conducted between January 2016 and September 2017, with a total of 119 participants consisting of 35 international mental health researchers and psychiatrists in the pilot stage, and 32 volunteers and 52 mental health professionals across the three European cities for the main study. None of the participants withdrew consent.

In the pilot stage, there were four focus groups with international mental health researchers, totalling 25 participants, and two focus groups composed of 10 international psychiatrists, conducted in English. In the main study, four focus groups with mental health professionals were conducted in each city: Brussels, London and Porto, with a total of 20, 16 and 16 participants, respectively. An additional two focus groups with volunteers at the same sites were assembled with a total of 9, 11 and 12 participants, respectively.

To facilitate meaningful data comparison across countries, the overarching themes and subthemes are presented in tables. Overarching themes are presented across countries and subthemes are presented for each country. The full list of subthemes complemented by an illustrative quote from a participant is provided in the online supplemental appendix 1.

Socio-demographics of participants

The overall sample (n=119) was mostly composed of women (n=78, 65.5%), with an age range of 21–68 years (mean=38.0, median=36.0). The majority had experience of volunteering (n=91, 76.5%), of which more than half had experience of volunteering in mental health (n=47, 51.6%). The tables provide more detailed information about the socio-demographics of the mental health professionals (table 2) and volunteers (table 3) from the three European countries.

Table 2.

Socio-demographics of mental health professionals

| Mental health professionals | London (n, %) | Brussels (n, %) | Porto (n, %) | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.8 (10.1) | 41.0 (11.0) | 33.4 (10.7) | |||

| Median (range) | 43.5 (28–63) | 44.5 (24–57) | 28.0 (26–58) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 12 | 75 | 8 | 40 | 11 | 68.8 |

| Male | 4 | 25 | 12 | 60 | 5 | 31.3 |

| Professional background | ||||||

| Psychiatrist | 5 | 31.3 | 3 | 15.0 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Psychiatrist in training | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10.0 | 11 | 68.8 |

| Psychologist | 2 | 12.5 | 5 | 25.0 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Nurse | 5 | 31.3 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Social worker | 3 | 18.8 | 3 | 15.0 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Occupational therapist | 1 | 6.3 | 5 | 25.0 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Experience in volunteering | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 56.3 | 13 | 65.0 | 10 | 62.5 |

| No | 7 | 43.8 | 7 | 35.0 | 6 | 37.5 |

| Experience in volunteering in mental health | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 33.3 | 8 | 40.0 | 3 | 30.0 |

| No | 6 | 66.7 | 5 | 25.0 | 7 | 70.0 |

Table 3.

Socio-demographics of volunteers

| Volunteers | London (n,%) | Brussels (n,%) | Porto (n,%) | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.2 (19.0) | 48.0 (11.0) | 38.4 (14.5) | |||

| Median (range) | 60.0 (23–68) | 50.5 (25–61) | 38.0 (21–66) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 6 | 54.5 | 5 | 55.6 | 9 | 75.0 |

| Male | 5 | 45.5 | 4 | 44.4 | 3 | 25.0 |

| Professional background | ||||||

| Healthcare professionals | ||||||

| Dentist | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 25.0 |

| Medical doctor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Nurse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Occupational therapist | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychologist | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Social worker | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Managers and senior officials | ||||||

| Educational manager | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Teaching and educational professionals | ||||||

| Teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Lecturer | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Special needs education teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Research professionals | ||||||

| Researcher | 3 | 27.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Security professionals | ||||||

| Security | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Secretarial professionals | ||||||

| Receptionist | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Information technology professionals | ||||||

| Information technology technician | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Media professionals | ||||||

| Journalist | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sales, marketing and related professionals | ||||||

| Vendor | 2 | 18.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Marketing professional | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cleaning professionals | ||||||

| Street cleaner | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Road transport/drivers | ||||||

| Driver instructor | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Civil servants | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Students | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Retired | 2 | 18.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16.7 |

| Experience in volunteering in mental health | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 54.5 | 7 | 77.8 | 2 | 16.7 |

| No | 5 | 45.5 | 2 | 22.2 | 10 | 83.3 |

Data identified revealed six main themes that were commonly found across all countries and stakeholders (box 1). The terminology used was a point of contention in many groups, prompting discussion on the actual definition of the concept of ‘volunteering’, and eliciting different reactions.

Box 1. Main themes.

There is a framework in which volunteering is organised.

The role of the volunteer is multifaceted.

Every volunteering relationship has a different character.

To volunteer is to face challenges.

Technology has potential in volunteering.

Volunteering impacts us all.

In these main themes, different subthemes have emerged from the data in different countries. These are presented below and summarised in each of the tables.

There is a framework in which volunteering is organised

While acknowledging that there is potential for volunteering programmes, a lot of the discussion and concerns covered practicalities and what was deemed feasible or good practice (table 4). This covered the different aspects of volunteering, from recruiting volunteers to supporting those that volunteer, including the motivations that drive someone to volunteer, how organisations should select volunteers and their responsibilities towards them once selected, including training volunteers and how to match volunteers, to the wider context in which volunteering is provided.

Table 4.

Theme: ‘There is a framework in which volunteering is organised’ and its subthemes

| London | Porto | Brussels | |

| Selection and motivations of volunteers | Volunteers’ motivations are key |

Volunteers can also be keen to gain something (Os voluntários também podem ter interesse em ganhar algo) |

Volunteers may wish to help (Les bénévoles pourraient vouloir aider) |

| Volunteers should be selected and assessed |

Volunteers selected, but based on which criteria (Seleção de voluntários, mas baseada em que critérios) |

Volunteers may be unsuitable (Les bénévoles pourraient être inadéquats) |

|

| All kinds of people can be a volunteer |

It is a paradox to select volunteers (É um paradoxo selecionar voluntários) |

There is a priori selection (Il y a une sélection a priori) |

|

| Responsibilities towards volunteers | Organisations are responsible for volunteers |

A check-up should be done on volunteers (Deve-se fazer um check-up dos voluntários) |

Must be a triangular relationship (La relation doit être triangulaire) |

| To train or not to train |

Training may or may not be important, depending on how much (Formação pode ou não ser importante, dependendo da quantidade) |

Advantages and disadvantages of training (Avantages et désavantages de la formation) |

|

| Matching and the right to be re-matched |

Matching on their characteristics (Emparelhar de acordo com suas características) |

Appropriate matching (Match approprié) |

|

| The strong volunteering culture in the UK |

Volunteering with rules and a structure (Voluntariado com regras e uma estrutura) |

Organisational framework with specific values (Une organisation avec des valeurs particulières) |

In the focus groups conducted in London there was concern about risk assessment, with some emphasising that volunteers should be carefully selected and assessed, while others felt that in principle all kinds of people can be a volunteer. Furthermore, the motivations of volunteers were deemed essential to be made explicit. In terms of the organisation, many highlighted that the organisations are the ones with a duty of care and responsibility towards the volunteers. Several participants pointed out that in the UK there is a strong volunteering culture, while reflecting on whether volunteers should or should not be trained. There was much discussion about what constitutes a good match, with some holding a view that matching should be based on shared interests and that volunteers should have the right to be re-matched.

But I think in the UK there is a culture of volunteering, like it’s quite strong—people rely on that quite a lot.

(London Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 4, Participant 14, Psychiatrist)

In Porto there was much questioning about the exact criteria that should be used to select volunteers, with others mentioning that it is a paradox to select volunteers. Views also covered the rules and structure for volunteering, with some suggesting that a regular risk assessment to check on volunteers should be done before and throughout. Beyond the notion that volunteers want to help others, some proposed that volunteers’ motivations could also be to gain something. There was also a discussion about whether training may or may not be important depending on the degree of training, as it may vary from simply receiving information to undergoing more thorough training, ultimately leading to the acquisition of skills. In relation to matching, it was suggested that this was based on the characteristics of patients and volunteers.

When a person says—to volunteer is not to expect anything in return—it’s a bit of a lie, because a person always ends up having something in return, isn’t it? Even if it’s just to feel good, like… I helped this person and I feel good, so … I already won.

(Porto Volunteer Focus Group 1, Participant 1)

In Brussels there were different views with some considering that volunteers should be selected and others deeming that there is already an ‘a priori’ selection, in that those individuals who take the initiative to volunteer already represent a self-selection for taking such role. Some described the potential motivations of volunteers as being to help others, to save others or to participate in a collective citizenship. Some have raised the issue that the organisational framework should have specific values and that the relationship was triangular, involving the volunteer, the volunteering organisation and the patient, focusing on the importance of an appropriate matching. The discussion around training was also present, describing its advantages and disadvantages, with views expressed both in favour and against training for volunteers.

Obviously it is a bond between two individuals but that this type of link can be fruitful only if it’s always three. The three being symbolic, but notably is the presence of an institution.

(Brussels Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 1, Participant 3, Social Worker)

In all sites there was much discussion about the importance of selecting volunteers and how to select them, and whether or not volunteers should be trained.

The role of the volunteer is multifaceted

There was a wide range of perceptions of the role of the volunteer, with multiple responsibilities attributed to it and a lack of consensus, which is reflected in the labelling of this theme (table 5).

Table 5.

Theme: ‘The role of the volunteer is multifaceted’ and its subthemes

| London | Porto | Brussels | |

| Passive | Be with |

Provide company and support the patient (Fazer companhia e apoiar o doente) |

Accompany patients (Accompagner les patients) |

| Give hope to |

Support patients to rediscover life (Ajudar os doentes a reencontrar sentido de vida) |

Give hope and return to who they were before the illness (Donner de l’espoir et retrouver qui ils étaient avant la maladie) |

|

| Not to judge patients |

A transition figure (Uma figura de transição) |

Not labelling patients (Ne pas étiqueter les patients) |

|

| Active | Address patients’ needs |

To keep an eye on the patient (Vigiar o doente) |

Respond to a need and offer what services do not (Répondre à un besoin et offrir quelque chose que le système n’offre pas) |

| Do social activities with |

Do social activities with (Fazer actividades lúdicas) |

Do social activities with (Faire des activités sociales) |

|

| Practice social skills |

Provide competencies (Capacitar o doente com competências) |

Helping patients (Aider les patients) |

|

| Share experiences |

Provide new experiences (Proporcionar novas experiências) |

Relational exchanges (Échanges relationnels) |

|

| Give patients realistic feedback |

Educate the patients (Educar o doente) |

Instil ideas into the patients (Insuffler des idées aux patients) |

|

| Collaborate with services |

To complement, liaise or be part of services (Como complemento, elo ou integrado nos serviços) |

Collaborate with or be part of services (Collaborer avec ou faire partie des services) |

The role of the volunteer was seen overall as providing support to the patient, but the ways to achieve this were quite diverse from a more passive role, that is, ‘be with’ and ‘give hope’, to a more active role, that is, ‘do social activities’ and ‘practice social skills’. There was particular focus on the expectations relating to communication with the patient, that is, ‘give patients realistic feedback’ and ‘educate the patient’, and also highlighting that this entailed a person-centred approach, that is, ‘addressing patients’ needs’ and a social element, such as to ‘provide company’ and ‘support the patient’.

In addition to the direct role of the volunteer towards the patient, an expectation of a more institutional responsibility towards others, where the volunteers ‘collaborate with services’ was listed in all three sites. Although several different roles were described across the three sites, some mentioned that even if the volunteer did not have a predefined objective, their role could still have a therapeutic effect.

In London, many of the subthemes covered a variety of practical activities that the volunteers could help patients with, for example, helping them to practise social skills, communicating with the patients and giving them realistic feedback, but also less ‘tangible’ aims, such as to give hope to patients or not to judge patients. Some argued for a more individualised approach, identifying their role as variable depending on the patients’ needs.

It would be useful to have a … [volunteer] who is able to give some realistic feedback…

(London Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 1, Participant 3, Occupational Therapist)

In Porto, views ranged from prioritising a more social element, such as ‘provide company and support the patient’ to ‘do social activities’ and facilitate them to acquire competencies, or just giving ‘new and unique experiences’, even if for a brief interaction. It was felt that even if participants did not learn anything long-term, the experience would still be beneficial and worthwhile for the patient. There was also a sense of the volunteer as a ‘healthy role model’, a standard that the patient could look up to, and a temporary ‘transition figure’ for the patient, who has an impact that remains beyond the end of the relationship. Thus, the patient could put into practice the skills they acquired in their real world, encouraging them to ‘rediscover the meaning of life’. These positive and hopeful views of encouraging the acquisition of further skills and autonomy were in contrast to the perception of the volunteer as the one that should monitor and ‘keep an eye’ on the patient.

The surveillance would end up being a consequence of the company. As long as the patient feels that he is accompanied, that can protect him.

(Porto Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 2, Participant 8, Psychologist)

In Brussels, the subthemes varied from practical support, that is, ‘accompany the patients’, ‘do social activities’ and ‘help the patients’, or somehow ‘instil ideas in the patients’ to not having a specific predefined objective and giving hope to the patients. Other views seemed to show an expectation that the volunteers would be different and somehow better than the rest of society, for example, less judgemental, less stigmatising. They would therefore be ‘offering something that the services don’t have’. Of note in Brussels, several quotes were quite reflexive, on occasion seeming to represent idealised views of the role of the volunteer, and there were fewer concerns expressed about potential harms of volunteering when compared with the focus groups from the other sites.

We give hope. This is very important hope, especially for mental health after the person can return thanks to this hope in a longer programme where they will be helped by other professionals and other volunteers for example.

(Brussels Volunteers Focus Group 2, Participant 8)

In all sites, there were views that the role of the volunteer should be instrumental, providing practical support in conducting social activities and, in addition, collaborating with services.

In Porto and Brussels there were some views about the role of the volunteer as a means to control the patients, either ‘keeping an eye’ on them in Porto, or ‘instilling ideas into patients’ in Brussels. In London this was not expressed in such a way, but rather giving ‘patients realistic feedback’, as opposed to overprotecting them or mistreating them.

Every relationship has a different character

There were various views about the character of the relationship, ranging from two extremes; a more formal relationship ‘with a contract’, to a more informal ‘friendship’, which has led to labelling this theme as ‘Every relationship has a different character’ (table 6). In the focus groups different participants held distinct views about the character of the relationship and equally, each participant believed that every relationship would be different.

Table 6.

Theme: ‘Every relationship has a different character’ and its subthemes

| London | Porto | Brussels | |

| Format | A contracted friendship |

A friendship by decree (Amizade por decreto) |

To be a friend or not (Être ami ou pas) |

| A mentorship |

A helping relationship (Uma relação de ajuda) |

A bond (Un lien) |

|

| It is reciprocal |

A reciprocal exchange (Uma partilha recíproca) |

A reciprocal relationship (Une relation réciproque) |

|

| It is patient-centred |

In limbo between a friend and a professional (No limbo entre um amigo e um técnico) |

A relationship between two people (Une relation entre deux personnes) |

|

| Not one size fits all |

A relationship hard to predict (Uma relação difícil de prever) |

The volunteer occupies a larger space in patients’ lives (Le bénévole occupe un espace plus grand dans la vie des patients) |

|

| It is time-limited |

It may or may not have a maximum time (Pode ou não ter um tempo máximo) |

A finite relationship (Une relation définie) |

|

| Boundaries | Explicit boundaries |

It is a contract (É um contracto) |

The relationship exists because of the mental illness (La relation existe à cause de la maladie mentale) |

| Fluid boundaries |

Became a friendship (Tornou-se uma amizade) |

With distance or proximity (Avec distance ou proximité) |

|

| May be compelled to break boundaries |

The trust is broken if the confidentiality is breached (A confiança quebra-se com a quebra de confidencialidade) |

There is a randomness for the relationship to work (Il y a un élément aléatoire pour que la relation fonctionne bien) |

In London, some of the subthemes expand on the format of the relationship as either a contracted friendship or mentorship, with some pointing to its reciprocity and others to the fact that it is not an ‘equal relationship’ as it is patient-centred and one size would not fit everyone. Some have highlighted that these types of relationships are time-limited and the difference lies in the explicitness of the boundaries. When these were tighter, people may be compelled to break them.

…like person-centred. So it depends on who you’re supporting and what their needs may be.

(London Volunteer Focus Group 1, Participant 3)

In Porto, views varied about the character of the relationship, from a friendship by decree, a reciprocal relationship or a helping relationship, and it may be in limbo between a friend and a professional. It was considered that this relationship may be difficult to predict, it may or may not evolve and it may or may not have a maximum time period. Some have described it as a relationship with boundaries, with some calling it ‘a contract’, and others raised the concern that trust is broken if the confidentiality is breached.

The volunteer… is a kind of intermediary between friend and professional… who is neither a professional nor a friend… is there in limbo.

(Porto Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 1, Participant 3, Psychiatrist in training)

In Brussels, views varied as to whether such a relationship was or was not a friendship, with some describing it as a reciprocal relationship and others believing there was some connection or ‘bond’. Some felt it was important to emphasise the dynamics of the relationship, whereby the relationship exists because of the mental illness. It was felt that the space that the volunteer occupies in the lives of the patients is disproportionately large compared with the space that the patients may occupy in volunteers’ lives. Some described its boundaries as a finite relationship and some have also spoken about demanding a duration and engagement from the volunteers. Others described that the relationship may have more or less distance or proximity, pointing out that there may need to be a randomness for the relationship to work, given that it involves two individuals that may or may not get along. Furthermore, it is a relationship commonly with a predetermined end.

The … space that the volunteer holds in the patient’s life is disproportionately large compared to the space that the patient holds in the life of the volunteer.

(Brussels Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 2, Participant 9, Psychiatrist)

Across sites, there was a view that it is not a naturally formed relationship, although it may be a reciprocal, two-way relationship with both sides benefiting. Much discussion occurred about the nature of the relationship being more or less artificial or more or less of a friendship, reflecting that the presence of many rules may make it challenging to create a friendship.

To volunteer is to face challenges

Several challenges, both barriers and risks, were related to the provision of volunteering, many of which were somewhat specific to the local context (table 7). The barriers described were at the organisational or individual level, preventing, either conceptually or practically, the establishment of volunteering or people taking steps to volunteer. The possibility of potential risks to those involved was raised, that is, relating to the patient, the volunteer, the organisation or the society. These concerns covered relationships that were not in the right format, too intense or toxic.

Table 7.

Theme: ‘To volunteer is to face challenges’ and its subthemes

| London | Porto | Brussels | |

| Barriers | Stigma is a big issue |

Lack of education and stigma of mental illness (Falta de educação e estigma da doença mental) |

Mental health stigma (Stigmatisation envers la santé mentale) |

| Odd or artificial idea to provide friends to people |

Being a novelty (Ser uma novidade) |

Bad image of volunteering (Mauvaise image du bénévolat) |

|

| Bureaucracy and time to get a Disclosure and Barring Service check |

Lack of resources (Falta de recursos) |

Lack of recognition (Manque de reconnaissance) |

|

| Problem with distances and transports |

Long distances (Distâncias longas) |

Complexity of dealing with the different languages in the country (Complexité de la gestion des différentes langues du pays) |

|

| Difficult to deal with differences of culture, religion and language |

Dealing with behaviour of patients (Lidar com o comportamento dos doentes) |

Dealing with someone with psychosis (Interagir avec une personne souffrant de psychose) |

|

| Risks | Selecting untrustworthy volunteers |

Involving others besides the volunteers (Envolver outras pessoas além dos voluntários) |

Volunteers do their own volunteering (Les bénévoles font leur propre bénévolat) |

| Burden for the volunteers |

Over-involvement of the volunteer and the patient (Sobreenvolvimento do voluntário e do doente) |

Being heavy for the volunteer (Lourd pour le bénévole) |

|

| Risk of over-professionalising volunteers |

Do a professional job, but not paid (Fazer um trabalho profissional, mas não pago) |

Risk of being unpaid work (Risque d’être un travail non rémunéré) |

|

| Providing a volunteer to a patient that is not interested |

Exposing patients to risky behaviours (Expor os doentes a comportamentos de risco) |

Volunteers not listening to the patients (Les bénévoles n’écoutent pas les patients) |

|

| Volunteers that undermine clinicians’ work |

Relationship is ‘toxic’ to the patient (Relação seja ‘tóxica’ para o doente) |

Manipulate the patient (Manipuler le patient) |

|

| To end the relationship |

Become dependent on the volunteer (Tornar-se dependente do voluntário) |

Risk of breaking the relationship (Risque de rupture) |

In London, much of the discussion was about the selection of volunteers; it is considered difficult and time consuming with regards to bureaucracy and the Disclosure and Barring Service checks. Once selected, other challenges were identified, such as the risk of selecting untrustworthy volunteers and the potential for volunteers to undermine clinicians’ work. Other challenges that emerged in the discussions concerned practicalities, either as a result of dealing with physical distances or differences of culture, religion and language. Some felt it could seem awkward to provide friends to patients. Other risks were centred around the format and the delivery of the relationship with overly high expectations of volunteers, not having the right relationship format or professionalising volunteers. Other concerns raised were more emotional, such as dealing with the end of such a relationship.

A slightly odd idea, to…artificially create, or provide friends to people; …that’s not how it works; and either you advise someone to go to speak to someone or meet with someone.

(London Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 4, Participant 14, Psychiatrist)

In Porto, many raised the lack of education and stigma of mental illness as a barrier for volunteering, which also extended to volunteers owing to their proximity to the patients. The fact that it was perceived as a novelty, the lack of resources and long distances were other barriers noticed. There was discussion and concerns about practicalities such as difficulties in dealing with patient behaviour, problems of the actual relationship, for example, being ‘toxic’ to the patients, having patients and volunteers overinvolved with each other, or exposing patients to risky behaviours. There were also concerns about volunteers carrying out an unpaid professional job, or patients becoming dependent on volunteers.

People who… would be available 24 hours … I don't know how healthy that was for the volunteer. It would stop… it would not be volunteering anymore, it would be a way of living…

(Porto Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 3, Participant 12, Psychiatrist in training)

In Brussels, the structural barriers described were the stigma of mental health, the negative image of volunteering, the lack of political and financial recognition of volunteering and the fact that there are different languages officially spoken in the city, that is, French and Dutch, and the complexity that this brings. The potential risks mentioned were volunteers wanting to do their own version of volunteering and not following the organisation’s rules, the risk of over-professionalising volunteers who ended up being an unpaid worker and patients being a burden to the volunteers, who may not know what to do if patients became ill. There were concerns around the format of the relationship with volunteers not listening to the patients, manipulating the patient and the risk of ending and breaking the relationship.

Unfortunately, volunteering does not have a very good image.

(Brussels Volunteers Focus Group 1, Participant 1)

In London and Porto there was the concern that distances may be difficult and act as a barrier for people to meet in person. In London and Brussels discussions raised challenges about dealing with different cultures and languages. In all sites, participants described the stigma of mental health as a challenge for volunteering.

Technology has potential in volunteering

The potential role of technology in volunteering in mental health was described in different ways, indicating both its advantages and disadvantages (table 8).

Table 8.

Theme: ‘Technology has potential in volunteering’ and its subthemes

| London | Porto | Brussels | |

| Advantages | Enables human contact |

Tool for patients to acquire skills (Ferramenta para os doentes adquirirem competências) |

Brings people together (Rapprocher les personnes) |

| Is an add on to the relationship |

It complements the physical relationship (Complementa a relação física) |

Complementary to the face-to-face relationship (Complémentaire à la relation face à face) |

|

| Links people in different cities |

Connects people (Aproxima as pessoas) |

Overcomes distances (Coupe les distances) |

|

| A few contacts per week |

Fewer contacts required (Necessária menor frequência de contactos) |

A brief telephone contact may suffice (Un petit contact téléphonique peut suffire) |

|

| Gives more control in what you want to share |

Enables one to monitor the communication (Permite monitorizar a comunicação) |

Takes away the spontaneity (La perte de la spontanéité) |

|

| Good for patients that have face-to-face anxiety |

Encourages the patient through sharing information (Incentiva o doente ao partilhar informação) |

Good for those who have anxiety in the face-to-face (Bon pour ceux qui ont une anxiété dans le face à face) |

|

| Disadvantages | Different types of communication may have an increasing human contact |

Face-to-face communication is preferable (Comunicação frente a frente é preferível) |

Each person occupies a different role on the phone (Chaque personne occupe une place différente au téléphone) |

| Takes away human interaction |

Risk of replacing the physical relationship (Risco de substituir a relação física) |

Unnecessary for the relationship (Pas nécéssaire pour la relation) |

|

| Put at risk what is essential, the relationship |

Risk of having an app only for patients and volunteers (Risco de se ter uma “app” só para doentes e voluntários) |

Not being transparent with the institution (Ne pas être transparent avec l’institution) |

|

| Patients becoming paranoid |

More difficult to establish boundaries (Mais difícil estabelecer limites) |

Technology can be invasive (La technologie peux être envahissante) |

In London, technology was seen as a tool that can help people, with some viewing it as an enabler of human contact and linking people in different cities, whereas others deemed it takes away human interaction. Similarly, some thought of technology as an add-on to the relationship while others felt it risks what is essential, that is, the relationship. It has been suggested that technology may provide people more control in what is said, enabling additional time to think and respond, which may be good for people that have anxiety around face-to-face contact. Of note, one of the participants highlighted that the different types of communication would allow different forms of human contact, which offer different amounts of access to the other person. In addition, there were concerns that technology could enhance the risk of patients becoming more paranoid.

If you’re telling people who might have paranoia that they are gonna be monitored, you’re gonna affect that relationship and it’s going to affect how people communicate with each other or how often, and I don’t think that’s a good idea, to monitor that.

(London Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 3, Participant 12, Psychologist)

In Porto, views varied as to whether technology was a complement or a replacement to the physical relationship, with some considering face-to-face communication preferable. Some saw technology as a tool for patients to acquire digital skills, while others mentioned that less frequent contact would be required. It has been suggested that technology may be helpful by sharing encouraging information to patients, such as a song or a picture, and that it may enable monitoring of communication between patients and volunteers. The difficulties to establish boundaries through technology were raised, for example, patients calling volunteers during non-social hours, although some provided suggestions on how to limit this. There was a strong view against having an application only for patients and volunteers.

I’m concerned of finding separate ways for this [communication]… when maybe the interest would be teaching the patient to use common tools, and not perpetuating the idea that I am a volunteer and he is a patient, and our relationship is different from the others, and we even have a different app to talk… I would prefer that the patients use the tools that other people do… because that [a separate app] perpetuates the idea that I’m sick and the others are normal.

(Porto Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 1, Participant 2, Psychiatrist in training)

In Brussels, views varied from technology bringing people together, being complementary to the face-to-face interactions, where a brief telephone contact may feel sufficient and that over the phone, each person occupies a different role, one being the caller, the other the listener. It has been reasoned that an advantage of technology is that there is better control over what is said and it may be good for those who have face-to-face anxiety. Others thought that technology may replace the face-to-face relationship, that it may risk losing transparency with the institution, or could be invasive.

Putting technology at the service of the human being it allows more. I work all over the planet with Skype, it allows… but what is crazy… it cuts the distances.

(Brussels Volunteer Focus Group 2, Participant 6)

In all sites, participants shared both advantages and disadvantages of the use of technology, although overall optimism prevailed over scepticism. In both London and Brussels participants emphasised the potential advantage of technology for those who have anxiety in face-to-face interactions.

Volunteering impacts us all

Several ways in which volunteering can have impact were discussed (table 9). These included the consequences on patients, volunteers, mental health professionals, as well as the impact on wider society.

Table 9.

Theme: ‘Volunteering impacts us all’ and its subthemes

| London | Porto | Brussels | |

| Patients | Promote patients’ recovery |

Patient always benefits even if they do not notice (O doente beneficia sempre mesmo que não se aperceba) |

Therapeutic effect for patients (Effet thérapeutique pour les patients) |

| Reduce patients’ social isolation |

Social integration of patients (Integração social dos doentes) |

Realise that they are more than a disease (Se rendre compte qu’ils sont plus qu’une maladie) |

|

| Volunteers | Make volunteers feel useful |

Volunteers satisfied helping others (Voluntários terem satisfação em ajudar os outros) |

Make volunteers feel useful (Faire en sorte que les bénévoles se sentent utiles) |

| Increase volunteers’ knowledge about mental health |

Occupy the volunteers and gain experience (Ocupar os voluntários e ganharem experiência) |

Volunteers gain professional experience (Bénévoles gagnent une expérience professionnelle) |

|

| Levelling for the volunteers |

Volunteers contact with a different reality (Voluntários contactarem com uma realidade diferente) |

Volunteers learn from the patients (Bénévoles apprennent avec les patients) |

|

| Clinicians | Can increase or decrease the mental health professionals’ workload |

Reduce the workload of health professionals (Reduzir a carga de trabalho dos profissionais de saúde) |

Reduce workload of mental health professionals (Réduire la charge de travail des professionnels de santé mentale) |

| Others | Can be a way of different people working together |

Release tension in relationships with family members (Libertar a tensão na relação com os familiares) |

Support an inclusive society (Soutenir une société inclusive) |

| Reduce stigma |

Break the stigma in society (Quebrar o estigma na sociedade) |

Reduce stigma (Réduire la stigmatisation) |

In London, volunteering was perceived as having a positive impact on patients’ recovery, improving their quality of life and reducing their social isolation. Volunteering was also deemed to have consequences for volunteers, making them feel useful, increasing their knowledge about mental health and being a levelling experience for them. As for the impact on the mental health professionals’ workload, some thought it could decrease if patients improved clinically. The possibility was raised that workload could increase if clinicians had the added task of monitoring the relationship. Some thought because of the latter, it may not have any overall effect on clinician’s workload. There were views about the impact this may have in services with different people working together, and at the wider society level, reducing stigma.

The benefits are quite crucial I think, for me … Improving quality of life in terms of socialisation and getting involved in activities—or even if it just means being able to go out in the community and have fresh air, because there are some clients with mental illness that to go out alone, they are quite frightened to go out and worried that something might happen to them—you know, just to get out and get fresh air is, is advantage for them.

(London Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 2, Participant 5, Nurse)

In Porto, participants thought volunteering could be helpful in the social integration and social acquisitions of patients, with some stating that patients always benefit, even when they do not notice it. In regard to benefits for volunteers, some pointed out that it would provide them with contact with a different reality, others highlighted that it would occupy volunteers and provide them with a new experience, and mentioned the satisfaction they may gain by helping others. The potential impact of volunteers in releasing the tension from patients’ family members and in reducing the workload of health professionals was also mentioned.

A volunteer who has [this] experience, not only in mental health but in any other contact, we win, the person who gives… because giving is much more rewarding than receiving …

(Porto Mental Health Professionals Focus Group 1, Participant 4, Psychiatrist in training)

In Brussels, views were shared about different ways through which volunteering would have a therapeutic effect for patients, for example, through patients realising that they are more than a disease. Some of the participants mentioned that volunteers would feel useful, may gain professional experience and learn from patients. Many stated that volunteering may reduce the workload of mental health professionals and support the wider society making it inclusive.

For me volunteering is also a personal need to contribute usefully to find a place in society to transmit knowledge that we have … it is really to exercise the … useful role in the society

In all sites participants shared that they felt that volunteering impacted not only the patients, but also the volunteers, mental health professionals, carers and the wider society. Views regarding the potential impact of reducing stigma that might come about through volunteering were present in all the discussions.

Discussion

Main findings

While these focus groups were conducted in three European countries chosen for their differences, overall, there were striking commonalities across the findings. Although two types of groups composed of mental health professionals and volunteers were organised, there were overlaps as some participants in the mental health professionals’ groups had experience in volunteering, and some participants in the volunteers’ groups had a professional background in mental health.

In this study, occupational homogeneity within each focus group was envisioned by organising the focus groups for mental health professionals and volunteers separately. However, there was heterogeneity within each group; within the mental health professionals’ groups, participants had different professional roles, and within the volunteer groups, not everyone had experience in volunteering in mental health.

Overall, there was more homogeneity among the mental health professionals, whereas the focus groups with volunteers were more heterogeneous. The differences in the local context of these three countries was reflected in the vocalisation of distinct challenges. The provision of volunteering in mental health in the UK is widespread, in Belgium it has links with healthcare services and in Portugal it barely exists. This familiarity in the UK with volunteering translated into participants reporting more concerns relating to practicalities, in Porto issues raised were related to local barriers and dealing with the unknown and in Brussels, participants were calling for more infrastructural support, that is, in policies and funds. Overall, participants largely reported that volunteering in mental health may be a helpful resource for people with mental illness and did not express much resistance against it, although it was considered that volunteers should be in contact with mental health services. On occasion there was a dissonance reflecting an underlying tension of paternalism in considering the responsibility of the volunteer or the organisation versus autonomy as core values of people with mental illness. In theory, participants approved of the use of volunteering in mental health. In practice, several questions were raised about how to overcome barriers and mitigate perceived risks, encouraging volunteering to become more inclusive. Stigma was both a barrier as well as a potential outcome for society, with all sites perceiving that volunteering could lead to reducing stigma. The various attitudes towards the connotation of the term ‘volunteering’ in the three languages may have influenced the later discussion of the actual behaviours that were labelled as acts of ‘volunteering’. One of the main findings of this study was that volunteering is not one single entity and that it is strongly connected to the sociocultural context, although with commonalities across countries.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to explore the views of mental healthcare professionals and volunteers regarding the provision of volunteering in mental health across European countries in different regions with varied sociocultural contexts. The benefits of this multiperspective approach, that is, focusing on three different countries and two groups of stakeholders, are well described, especially in the field of intimate relationships.22 It offers a richer understanding of stakeholders’ opinions and an improved portrayal of the complexity of relationship dynamics.

The methodology used was consistent across sites in terms of recruitment and acknowledgement of participation. In contrast, other international focus groups conducted in eight European countries which explored what good health and good care process means to people with multimorbidities adopted more flexibility in their methodological approach across the sites. Participants were reimbursed for their travel costs in some countries, whereas in others a gratuity was provided either as a token of appreciation or to aid recruitment. In some cases, participants were emailed after the meeting to thank them for their participation; in one country participants were sent notes.23

A large sample of mental health professionals and volunteers was recruited, enabling the capture of a rich picture of the stakeholders’ views from different backgrounds. The focus groups’ composition was largely reflective of the healthcare and volunteering services organisation in each country. In all three nations, mixed focus groups were composed of different mental health professionals. They were integrated as a group as they share understandings and experiences concerning mental healthcare provision. Their role was to explore the diversity of views as professionals working in mental health, rather than to establish any kind of 'representativeness'.

Conducting this study as a multicountry collaboration was helpful as the research team members could interact and learn from each other. The research team was multidisciplinary, with a background in psychiatry and psychology, and different experiences in volunteering in mental health. This diversity enabled the interpretation to be informed by different perspectives. The fact that in all sites a second researcher, who co-facilitated the focus groups discussion, coded all the data are a major strength and provides robustness to the analysis. The pilot stage exploring the feasibility of organising such focus groups is another strength of this study. This allowed assessment of the potential challenges in the recruitment and interview phase, analysis and study materials as well as providing an appreciation of the facilitator’s workload.

Despite its originality, this study also has some limitations.

While focus groups were conducted in three European cities, some of the participants recruited, especially volunteers, were based in other parts of that country. However, this information was not acquired, which could have been particularly relevant in Belgium to explore potential differences between views in the Flemish and Walloon regions.

The large amount of data gathered provided opportunities for a broad analysis across countries, but there was limited capacity for detailed examination of the differences between mental health professionals and volunteers. In the current analysis the focus was on drawing out salient analytical points that were illuminated by the breadth of the data.24

Finally, although participants were given a brief description of volunteering in mental health before the beginning of the focus groups, it is unclear whether having a more comprehensive understanding or previous personal experience either on volunteering programmes or as a patient in mental health influenced their expressed views, although no information regarding the latter was requested for this study.

Comparison with the literature

The findings of these focus groups allude to six main overarching themes.

The first theme highlights that there is a framework on which volunteering is organised. It addresses several matters that a volunteering organisation may focus on, from the selection and motivations of volunteers to other aspects of dealing with those volunteers recruited to an organisation, that is, training of volunteers and the format of the relationships established. Much of the current literature is focused on volunteers’ experiences, motivations and organisational descriptions of the programmes.25–27 Volunteering programmes are dependent on staff management and the volunteers; they therefore require financial and human resources. Important variations were noted regarding how this framework was described, in some cases pointing to a lack of recognition and resources, whereas in others, showing preoccupation with dealing with the unknown.

The second theme highlights a wide range of perceptions of the volunteer role, labelled as multifaceted. It suggests that there is a broad flexibility in the understanding of what a volunteer should do, which in turn may mean that a large number of people may be suitable to be a volunteer. The perspectives on this ranged from a more passive role, of being with the patient and offering hope, to a more active role, such as doing social activities and practising social skills. This emphasis of ‘being there’ or ‘doing for’ is similar to that which has been described in other research, that is, in a qualitative study in mental health with volunteers and patients from 12 UK volunteering mental health programmes.28 These findings support that the manner in which volunteer roles are adopted may impact differently on the patient. In all sites, many participants discussed that volunteers should collaborate with services. A qualitative study conducted in Finland about the perceptions of volunteers by healthcare staff showed that attitudes were positive to conditional; these approaches varied from holistic to task-centred or patient-centred.29 Equally, a former study conducted in the USA explored the impact of using volunteers to improve patient satisfaction in hospitals and cost-effectiveness. They reported that volunteers appeared to enhance patient satisfaction and reduced costs.30

The third theme describes that every relationship has a different character, categorising relationships in several types of formats. Essentially, they fall into two extremes, that is, a more formal relationship that has a contract and is closer to a professional one, and a more informal interaction similar to or indeed a friendship. A former review of the term befriending has already described the spectrum of such relationships.1

The fourth theme highlights the challenges faced by a volunteer, that is, the barriers and risks. It describes different obstacles that prevent people from volunteering together with the perceived risks to those who volunteer. Previous research describing the barriers to the use of web-based communication in voluntary associations has pointed to the size and complexity of associations and to the obstacle of an age-based digital divide, that is, to have a profile on a social network site.31 A rapid review of barriers to volunteering for potentially disadvantaged groups and implications for health inequalities suggested that although different demographic groups may experience specific barriers to volunteering, there were areas of commonality. These included personal resources, that is, skills, qualifications, time, financial cost, health or physical functioning, transportation or social connections and institutional factors, such as volunteer management, access to opportunities, lack of appropriate support and a stigmatising or exclusionary context.32 A further study described specific impediments for older people becoming volunteers,33 for example, their own health, perceiving volunteering as an unworthy cause or as an unknown prospect.

The fifth theme, exploring the potential advantages and disadvantages of technology use in volunteering, overlaps with former insights into patient–clinician communication through technology. It highlighted similar enthusiasms and scepticisms. Potential benefits and problems of the human–machine interface were previously described, as well as the appropriateness of a specific technology in a specific situation.34 Among these ongoing debates, some argued that the potential advantages outweigh the disadvantages.35 Overall, these findings show an interest in using digital platforms as a resource for volunteering, which aligns with the views offered in previous literature.36 37 A qualitative analysis of social and digital inclusion, experienced by digital champion volunteers in Newcastle, reported four categories of motivations leading to successful volunteering, that is, the individual, people, employment and environmental factors.38

The last theme illustrates that volunteering impacts us all, and describes the potential impacts of volunteering on patients, volunteers, mental health professionals, families and the wider society. The broader impact of volunteering beyond the aimed effect in patients has been earlier described in a systematic review that postulates that it is a public health intervention.39

Implications of the findings

These findings represent the views of mental health professionals and volunteers and may be used to inform the development and organisation of current and future volunteering programmes.

Since this study was based in high-income countries in Europe, it is unknown whether these findings would also apply to LMICs; this should be investigated further. Additionally, it is uncertain how specific these results are to this sample and to these cities. Future studies should explore whether these findings differ for participants in the rest of the countries and abroad.

The variability of opinions suggests that volunteering programmes should be offered in different formats and with enough flexibility to incorporate individual preferences. An important point was the strong belief that there is potential with technology. This can help with the development of new interventions to facilitate digital forms of volunteering.

Conclusions

Mental health professionals and volunteers consider it beneficial offering volunteering opportunities to their patients. The variability of their views suggests a need for flexibility and innovation in the design and models of programmes offered to patients and volunteers. It is possible, however, that a single intervention based on the common principles could suit different European countries without requiring significant customisation for each country.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @_Maev_C

Contributors: MPdC designed the study, led the recruitment of participants, coordinated the study, managed the study team, facilitated the focus groups, led the analysis of the data and drafted this manuscript. MC, FMdS and ST co-facilitated the focus groups and supported with the data analysis. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: MPdC research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames at Barts Health NHS Trust, the East London NHS Foundation Trust, the Queen Mary University of London and the Befriending Networks in the UK; in Belgium by the Université Catolique de Louvain; in Portugal by the Hospital de Magalhães Lemos and the Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar at the University of Porto; and by the European Psychiatric Association.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement :Participants were only asked to consent to their anonymised quotations to be used in publications.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics approval

This study received approval from Queen Mary University of London (Reference number: QMREC1665a).

References

- 1.Thompson R, Valenti E, Siette J, et al. To befriend or to be a friend: a systematic review of the meaning and practice of "befriending" in mental health care. J Ment Health 2016;25:71–7. 10.3109/09638237.2015.1021901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons M, Wijkstrom P, Clary G. Comparative Studies of Volunteering: What is being studied’ Voluntary Action 199;1:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stebbins RA. Volunteering: a serious leisure perspective. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 1996;25:211–24. 10.1177/0899764096252005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cnaan RA, Amrofell L. Mapping volunteer activity. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 1994;23:335–51. 10.1177/089976409402300404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cnaan RA, Handy F, Wadsworth M. Defining who is a volunteer: conceptual and empirical considerations. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 1996;25:364–83. 10.1177/0899764096253006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handy F, Cnaan RA, Brudney JL, et al. Public perception of “Who is a Volunteer”: An examination of the net-cost approach from a cross-cultural perspective. Voluntas 2000;11:45–65. 10.1023/A:1008903032393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meijs LCPM, et al. All in the Eyes of the Beholder? Perceptions of volunteering across eight countries. In: Dekker P, Halman L, eds. The values of Volunteering: cross-cultural perspectives. New York, Boston, Dordrecht, London, Moscow: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2003: 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle D, Crilly T, Malby B. Can volunteering help create better health and care?, in commissioned by the HelpForce fund. School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huppert FA, Marks N, Clark A, et al. Measuring well-being across Europe: description of the ESS well-being module and preliminary findings. Soc Indic Res 2009;91:301–15. 10.1007/s11205-008-9346-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partnership M. The ‘Hidden’ Workforce Volunteers in the Health Sector in England 2009.

- 11.Naylor C, C M, Weaks L. Volunteering in health and care: securing a sustainable future. London: King’s Fund, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCorkle BH, Dunn EC, Wan YM. Compeer friends: a qualitative study of a volunteer friendship programme for people with serious mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2009;55:291–305. 10.1177/0020764008097090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook H, Inman A. The voluntary sector and conservation for England: achievements, expanding roles and uncertain future. J Environ Manage 2012;112:170–7. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanderstichelen S, Cohen J, Van Wesemael Y, et al. Perspectives on Volunteer-Professional collaboration in palliative care: a qualitative study among volunteers, patients, family carers, and health care professionals. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:198–207. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanderstichelen S, Cohen J, Van Wesemael Y, et al. The involvement of volunteers in palliative care and their collaboration with healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional volunteer survey across the Flemish healthcare system (Belgium). Health Soc Care Community 2020;28:747–61. 10.1111/hsc.12905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]