Abstract

Introduction

Prescribing and medication use in palliative care is a multistep process. It requires systems coordination and is enacted through activities of patients, informal carers and professionals. This study compares practice to idealised descriptions of what should happen; identifying when, how and why process disturbances impact on quality and safety. Our objectives are to:

Document an intended model (phase 1, scoping review).

Refine the model with study of practice (phase 2, ethnography).

Use the model to pinpoint ‘hot’ (viewed as problematic by participants) and ‘cold’ spots (observed as problematic by researchers) within or when patients move across three contexts-hospice, hospital and community (home).

Create learning recommendations for quality and safety targeted at underlying themes and contributing factors.

Methods and analysis

The review will scope Ovid Medline, CINAHL and Embase, Google Scholar and Images—no date limits, English language only. The Population (palliative), Concept (medication use), Context (home, hospice, hospital) framework defines inclusion/exclusion criteria. Data will be extracted to create a model illustrating how processes ideally occur, incorporating multiple steps of typical episodes of prescribing and medication use for symptom control. Direct observations, informal conversations around acts of prescribing and medication use, and semistructured interviews will be conducted with a purposive sample of patients, carers and professionals. Drawing on activity theory, we will synthesise analysis of both phases. The analysis will identify when, how and why activities affect patient safety and experience. Generating a rich multivoiced understanding of the process will help identify meaningful targets for improvement.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval granted by the Camden & Kings Cross NHS Regional Ethics Committee (21/LO/0459). A patient and public involvement (PPI) coinvestigator, a multiprofessional steering group and a PPI engagement group are working with the research team. Dissemination of findings is planned through peer-reviewed publications and a stakeholder (policymakers, commissioners, clinicians, researchers, public) report/dissemination event.

Keywords: palliative care, qualitative research, quality in health care, therapeutics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There has been no previous mapping of idealised intended multistep processes associated with prescribing and medication use in palliative care.

Evidence of real-life practices of prescribing and medication use in palliative care across different contexts will illuminate understanding underlying themes and contributing factors to disruptions in intended processes.

Analysis of activity systems, comparing between the intended and practice process models, will inform areas to target innovation and improvement.

This study adopts the method of activity theory analysis to interrogate local service provision in palliative medication use in one area of England, but can offer a template by which to investigate prescribing also in other clinical and geographical areas.

The cross-sectional design will provide a detailed snapshot of activity but cannot formally track longitudinal change due to resource limitations.

Lay summary (developed with patient and public involvement coinvestigator)

Background

People with palliative care needs use prescription medications to achieve symptom control. ‘Daily hassles’ with medications are commonly reported. What happens in ‘real life’ and the effort required to achieve effective medication use in palliative care is poorly understood.

Aims

The study will collect information from patients, carers and professionals to:

-

Map ‘real life’ practices underlying medication use including:

Decision-making.

Prescribing.

Monitoring and supply.

Use (administration).

Stopping/disposal of medications.

Moving across healthcare and other contexts, such as homes.

Understand challenges patients and carers face and what they do/do not do to achieve effective medication use.

Understand impact of professional practices on medication use.

Design and methods

Three types of context will be identified in order to recruit from home, hospital and hospice. We will develop a pictorial (visual) process model of how using prescription medications should work in palliative care. We will then observe and explore what really happens and collect information about people’s experiences of medication use to develop a ‘real life’ model. Activity theory (AT), which can be used to good effect in analysing healthcare processes and practices, will help us to understand what happens, who does what, and what occurs when a patient moves across contexts.

Patient and public involvement

Consultation with patients, families, friends, carers and healthcare professionals helped us to develop this proposal. A patient and public involvement (PPI) coapplicant and co-author is part of the team, they will:

Provide an ‘expert-by-experience’ perspective.

Assist the research team to engage a wider PPI population.

Coproduce study dissemination products and activities.

All participants will be invited to a dissemination event and receive the study report.

Introduction

Prescribing and medication use for symptom control in palliative care is a multistep process that encompasses everything from identifying need to deciding what to prescribe, prescribing, dispensing, delivering, use/administration and disposal. Each step involves complex risk-prone tasks with frequent errors.1–8Of 475 NHS (National Health Service, England and Wales) serious incident reports (2002–2014) involving palliative patients, 91 (~20%) related to medications.9 These mostly occurred in patients’ own homes, half of which were when care was not provided by specialists.

Evidence specific to prescribing, medication use and error prevention in palliative care is scarce, with an absence of studies of the multiple steps involved or how these link in practice.10 Absence of evidence prevents policy and other interventions targeting underlying themes and contributing factors when problems occur.11 A better understanding of practices experienced, as distinct from intended processes, can identify targets for system change, new ways of working and new forms of practice.12–16 To address this, the multistep process of prescribing and medication use should be conceptualised as a series of socially constructed practices in which patients, informal carers and professionals are required to collaborate across locations and organisational boundaries.17–19

Optimal prescribing and medication use are influenced by ‘etiquette’; socially mediated evolutionary rules and boundaries, with unclear divisions of labour, shaping practice and disrupting intended processes.10 20–28 Expectations of primary and acute care professionals prescribing for symptom control29 contrast with reported hindrances of lack of time, confidence and skills.30–32 Existing research17 33 also reports high patient/carer workload, all groups involved experiencing struggles with multistep processes and practices, plus a lack of shared understanding of roles and responsibilities between patients/carers and different professionals.33 34 Often only patients (and by proxy their carers) experience all components of healthcare systems, as they move across contexts, gaining insight into where system redesign is needed.14 This protocol addresses a ‘high priority research area that is important clinically and in the community, as mismanaged medication can be frightening for carers and families’.35

Methods and analysis

Aims

Compare how prescribing and medication use appear in practice to idealised descriptions of what should happen in the multistep process.

Identify when, how and why process disturbances affect quality and safety.

Research questions

What are the experiences of patients, carers and professionals of prescribing and medication use?

Who does what, when and where in the multistep process of prescribing and medication use for symptom control in palliative care?

What impact do differences between the idealised intended process and the realities of practice have?

Objectives

Prescribing and medication use in palliative care will be studied across three contexts: community (home), hospital and hospice to:

Document an intended model of activities and outcomes of prescription medication use in palliative care for symptoms control …. (phase 1, scoping review).

Refine and elaborate the model with an ethnographic study of what happens in practice (phase 2, ethnography).

Use the refined model to pinpoint ‘hot’ spots (viewed as problematic by participants) and ‘cold’ spots (observed as problematic by research team) within a single context or when patients move across hospice, hospital and home contexts.

Create a learning and recommendation toolkit for improvement targeted at understanding underlying themes and contributing factors to process disturbances in practice.

Theoretical orientation and study design

This study draws on AT (also known as Cultural-Historical-Activity-Theory)36 to examine processes and practices including workarounds dependent on interactions between the agency of people and system structures. It extends and complements the work of others37 38 through a systematic view of patient safety and risk in palliative care, applied to prescribing and medication use.

Our approach builds on a proof-of-concept study in antibiotic prescribing.10 An identified limitation of this antibiotic study was the single perspective (captured solely in interview data) and single setting. Our work will offer an in depth analysis of ‘what happens on paper’ and ‘what happens in the real world’ of the palliative care medication activity from multiple perspectives within and across multiple contexts.39

The concept of activity describes ‘the fundamental interaction between humans and the world —humans behave actively toward the world (fragments of it), change it (them), and change themselves in this process. Humans as active subjects make fragments of the world objects (goals) of their activity and the same time are affected by the world (fragments of it)’.40 Definitions and an explanatory figure of other key AT concepts are in online supplemental table 1 and online supplemental figure 1.

bmjopen-2022-061754supp001.pdf (187KB, pdf)

Because AT considers reciprocal interactions between (1) theory and practices and processes and (2) systems and people (community), it provides a framework to analyse how interactions evolve (or fail), when a group of people are (or should be) working to achieve a shared goal.41

AT acknowledges that intended process descriptions differ from actual execution because processes are only partially scripted strings of actions, influenced and interacting with other parallel processes.42 43 This is especially important in palliative care since provision is within and across complex contexts, encompassing multiple providers and communities. To conduct our analysis, we will work from the perspective of patients’ activity systems focused on the object (goal) of achieving symptom control through accurate and effective prescribing and medication use. A theoretically informed, empirically evidenced model will be produced to identify targets for innovation and improvement in prescribing and medication use across palliative care contexts.

The study has two phases: a scoping review and an ethnographic study. In the final analysis the findings from each of these will be synthesised together to meet the overarching objectives of the work.

Patient and public involvement

This study addresses issues identified by the James Lind Alliance Palliative and End-of-Life Care Priority Setting Partnership.44 The PPI coinvestigator was recruited to coproduce the study from inception. Two independent PPI representatives were consulted (prefunding and postfunding award) in addition to sharing the study design with the Marie Curie Research Voices PPI group. A PPI engagement group (n=10) has been recruited. Consultation with stakeholders through our PPI and Steering Groups (clinical and methodology experts) will continue throughout study execution and dissemination.

Study dates

Initial searches were conducted July 2021 to develop the search strategy protocol (phase 1). The main study commences February 2022. The study end date is October 2023.

Phase 1: scoping review

This scoping review will use the nine-step Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework methodology.45–48

Step 1: review objectives

We seek to identify key definitions, concepts, characteristics and factors related to activities and outcomes of prescription medication use in palliative care for symptoms control. Specifically, the review objectives are to establish evidence for an idealised intended process for prescribing and medication use, documenting from whose perspectives, and what contexts this has been studied. We will also note any evidence of challenges in the process steps, and proposed solutions to these, to guide the empirical ethnography of phase 2.

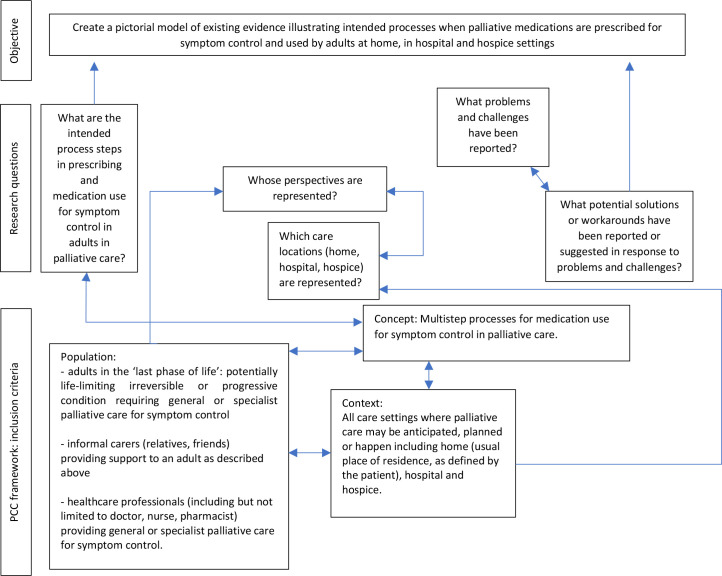

Step 2: aligning the inclusion criteria with objectives

Figure 1 demonstrates the relationship between the review objectives, questions and inclusion criteria. The Population (receiving palliative care), Concept (prescribing and medication use), Context (home, hospice, hospital) framework defines our inclusion criteria (figure 1). Exclusions are shown in box 1. We will include empirical research (quantitative and qualitative), review studies (if answering a novel question), policy documents, practice standard and guidelines, organisational flow charts, and reports focusing on how the processes should occur or gaps between any benchmark and what does occur. No date limits, English language only.

Figure 1.

Relationship between review objectives, questions and inclusion criteria.

Box 1. Scoping review exclusion criteria.

Studies focussed on neonatal, paediatric or adolescent populations.

Studies on palliative care as a result of trauma or attempted suicide.

Studies focussed on medication prescribed for indications other than symptom control or generic medication use principles without application to palliative care.

Ethical dilemmas associated with prescribing in palliative care. Opinion pieces, anecdotes, editorials, narratives or commentaries without reference to any form of intended process or practice (eg, solely first person experience of studies focussed on medication prescribed for indications other than symptom control or generic medication use principles without application to palliative care. Ethical dilemmas associated with prescribing in palliative care.

Opinion pieces, anecdotes, editorials, narratives or commentaries without reference to any form of intended process or practice (eg, solely first person experience of prescribing or medication use).

Evidence that has a pharmacological focus other than medication use e.g. pharmacokinetics.

Step 3: design for evidence searching, selection, data extraction and presentation

Preliminary searches of Prospero, Medline (Ovid), CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost), Embase (Ovid), Open Science Framework and JBI Evidence Synthesis (July 2021) established absence of an evidence-based understanding for prescribing and medication use in palliative care. This will therefore be followed by a comprehensive second search, reference and citation snowballing.48 To gain an overview of the scope of evidence we will undertake an iterative mind-mapping exercise to extract descriptive data of process steps before using the richest sources of data to chart using an extraction form (online supplemental file 2) and then build into a model illustrating how processes ideally occur, incorporating the multiple steps of typical episodes of prescribing and medication use for symptom control.

Step 4: searching

The review will scope Medline Ovid, CINAHL (EBSCO) and Embase Ovid, Google Scholar and Google Images (seeking organisational flow charts and policies). Keywords and index terms in relevant papers identified in the preliminary search together with stakeholder suggestions49 form the comprehensive search strategy (see online supplemental file 3) for this in Medline Ovid). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Department of Health, NHS England (also includes Wales), NHS Scotland and other UK policy data policy database searches will be conducted. All identified citations will be uploaded into Endnote and deduplicated. Reference and citation snowballing will be undertaken in Scopus for included full-text sources. The reviewers will contact any relevant authors for additional information if required. Further searching for unpublished evidence will occur iteratively, following leads from the above and/or recommendations from local collaborators. This will enable us to contextualise our empirical data within a localised scoping of the intended processes.

Step 5: selecting evidence

Titles and abstracts, then full texts will be independently screened by two independent reviewers (SY and SAF). Disagreements will be resolved by discussion, if required, with a third reviewer. The results of the search will be reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews.50

Step 6: extracting evidence

Our data extraction is designed around a basic process framework of decision-making, prescribing, monitoring and supply, use (administration), stopping/disposal of medications and moving across healthcare contexts.

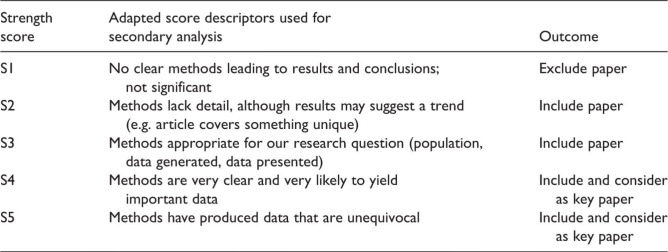

Following initial mapping by two researchers, one (S-AF) will chart essential descriptive data: authors, year of publication, country of origin, main aim, study design, perspectives represented (context (home, hospital, hospice or transitions between these), process steps included, problems and challenges reported, potential solutions or workarounds suggested. Although we will not exclude studies on the basis of quality, we will use a 5-point ‘strength score’ to stratify evidence (figure 2). A second researcher (SY) will verify charting for consistency and rigour. Interim findings will be discussed with the wider research team, steering and engagement groups to ensure focus remains on ‘what matters most’. Any iterative modifications to the draft data charting tool will be detailed in the full report.

Figure 2.

Strength score (Researcher-derived strength score descriptors adapted for use in quality assessment for secondary analysis51).

Step 7: analysis

We will draw on the model of the intended processes developed by Kajamaa et al10 in their AT analysis of antibiotic prescribing, together with our own provisional model developed from stakeholder engagement in prescribing and using palliative medication.49 Once we have established the range, methods and content of existing evidence we will consider if further analysis is likely to add new interpretations, such as using meta-ethnography techniques.51

Step 8: presentation of results

The evidence will be presented as a model with accompanying descriptive summary representing all parts of the multistep intended processes that have been studied, from each perspective and in which context. The model will expose problems, challenges and potential solutions or workarounds in existing sources, as well as help to identify evidence gaps.

Step 9: Summarising, making conclusions and noting implications

We intend to refine and elaborate the model during the empirical ethnography of what happens in practice (phase 2) by asking participants to ‘think aloud’ about the multistep processes, drawing on the intended model derived from the scoping review as a prompt on which to elaborate.

Phase 2: empirical ethnography

A rapid, focused ethnography will be conducted using a cross-sectional approach.52

Setting

An English local health economy functioning as a meta-system of palliative care provision incorporating NHS and voluntary sector services. Within this, the contexts of hospital, hospice and ‘home’ function as three interacting systems. Previous work on prescribing experiences identified greater differences within each context studied than across different contexts.10

We will use a minimum of one acute hospital, one community palliative care team and one hospice as study sites. We anticipate also using additional sites such as general practices and community pharmacy services. We have defined ‘home’ as a person’s usual place of residence within a community setting: this might be a private home, supported living, care home or other dwelling.

Recruitment and selection

The study population groups are defined in box 2. We will work with a lead local clinical collaborator at each site to identify potential participants. Recruitment strategies include poster advertising, presentations and provision of study materials for dissemination to professionals/patients/carers. Participants will be purposively selected by role and site for interviews as shown in table 1. A similar range of participants will be sought to participate in observation work. Exclusion criteria are:

Box 2. Study population groups.

-

Patients: The person receiving palliative care, including either direct or indirect care from a specialist team.

Inclusion criteria: The ‘last phase of life’ is defined as having potentially life-limiting irreversible or progressive conditions requiring general or specialist palliative care. Patients may have prognoses between weeks and short years. Receiving one or more prescription medications for symptom control. The study remit includes all medications used by patient when this criterion is met. Over the age of 18 years.

Carers: Anyone identified by the patient as having a role supporting them in their healthcare needs or illness who is not doing so because they are employed to do so. Carers can include family, friends, neighbours and/or anyone else who is important to the patient. Paid carers who are employed by a health or social care agency or other organisation are not included in this definition as medication use is usually explicitly excluded from their employment remit.

Ward doctors/nurses/pharmacists: professionals working in inpatient wards of hospices or hospitals.

Clinical nurse specialists in palliative care: Clinical nurse specialists in palliative care working within either hospital or community specialist palliative care services.

Palliative Medicine Doctors: Specialty trainees and consultants working within either hospital or community specialist palliative care services.

Non-medical prescribers: Professionals who are not doctors but who are qualified to prescribe medications for symptom control. May include nurses, pharmacists or other professionals.

Community pharmacists: May include pharmacists employed by NHS Trusts, clinical commissioning groups, general practice or independent pharmacists (running their own business or employed in the private sector to provide high street pharmacy services).

-

District nurses: Community nurses providing care to people at home.

GPs, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

Table 1.

Purposive sampling strategy for interviews

| Hospital | Hospice | ‘Home’ (usual place of residence) | Total |

| Patients (n=5) | Patients (n=5) | Patients (n=5) | 15 |

| Informal carer (eg, relative, friend) (n=5) | Informal carer (n=5) | Informal carer (n=5) | 15 |

| Ward doctors (n=2) | Ward doctors, not specialising in palliative care (n=2) | GPs (n=4 individuals from at least two different practices) | 8 |

| Ward nurses (n=3) | Ward nurses (n=3) | District Nurses (n=3) | 9 |

| Clinical nurse specialists(CNS) in palliative care (prescribers and non-prescribers) (n=4) | Any non-medical prescribers available and willing to participate (n=2) | CNS palliative care (prescribers and non-prescribers) (n=4) | 10 |

| Palliative medicine doctors (n=2) | Palliative medicine doctors (n=2) | Palliative medicine doctors (n=2) | 6 |

| Ward pharmacists (n=2 or all willing to participate if fewer than two working in this field) | Hospice pharmacist (n=1) | Community pharmacists (n=3) Community NHS Trust Pharmacist/outreach pharmacist (n=1 if post filled and willing to participate) |

7 |

GPs, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

Not employed within, sharing care with or receiving care from the services under study.

Clinical grounds/concern relating to psychological distress flagged by healthcare teams.

Data generation

Direct observations (n=15 whole day equivalents) of everyday work and practices, plus informal conversations around the acts of prescribing and medication use, will be undertaken. We are seeking ‘typical’ process examples and so will not be selecting sites in the expectation of particularly positive or negative experiences. Doctors, nurses and pharmacists will be shadowed, and asked to describe processes, giving examples of decisions, practices and significant events. The researcher will engage patients, and if present, informal carers in informal conversations during the observations. For example, while the researcher is shadowing a professional who visits a patient, the patient and/or others in the household might be asked to show the researcher anything they use to help them remember or manage their medications, or how they store their medication, and the researcher will make note of any items around the room or house that may be contributing to medication practices.

Following these, semistructured interviews will be conducted with a purposive sample of patients, informal carers and professionals in which we will explicitly discuss our model (see online supplemental file 4).

Data collection methods will include field notes, including pictorial representations of processes, during observations and videorecording/audiorecording of interviews. In addition, the research team will keep reflective diaries and notes of team discussions.

Contingency plans have been made to transfer the ethnography to a remote working design in the event of further COVID-19 restrictions.

Data analysis

Reflexive analysis concurrent with data collection will allow iterative exploration of the data within the AT framework. Constant comparative thematic coding of activities/work/effort related to prescribing and medication use will be undertaken. The presence or absence of reference to each model step will be coded, identifying volume of talk: ‘hot spots’— memorable examples and stories related to incidents, disturbances, learning experiences and ‘cold spots’—areas that are not talked about (but may still be problematic)

Disturbances in the process will be analysed to categorise types and identify underlying themes and contributing factors. The precedent study using this methodology in antibiotic use identified five categories: consultation challenges, lack of overview, process variation, challenges of handover, loss of the object (goal).10 We will specifically seek these while remaining alert to new and alternative categories. Attention will be paid to normal and out-of-hours care, different contexts and points of transition.

Synthesis of phases 1 and 2

AT provides a framework to make sense of data, building a rich multivoiced picture of work and effort. Ethnographic findings will be integrated with the initial process model to develop it into an experience/practice-based model for practices to ensure people with palliative care needs receive the right medications and with the right support at the right time. We will identify how symptom control can best be effective when processes are distributed across roles and contexts as well as using the final model to identify safety concerns with a focus on understanding underlying themes and contributing factors so that these can become targets for intervention and improvement.

Ethics and dissemination

NHS Regional Ethics Committee approval has been obtained. A multiprofessional/expert steering group is supporting the research team. We have consulted widely to consider ethical issues. We recognise that participants may find discussing care and service provision distressing if this prompts reflection on examples where all did not go well. Equally, some participants may find the research encounters therapeutic or useful for reflexive professional practice. We will develop a support protocol for this with each local site/clinical team and will signpost to, or facilitate, referral to additional services as necessary. Both the research fellow (registered pharmacist) and the CI (doctor) are experienced in working in clinical settings and adhering to the standards of confidentiality required.

Anticipated outcomes

Understanding the effort and work practices required day to day in the use of prescription medications, and the underlying themes and contributing factors in disruptions is crucial to designing, testing and implementing more efficient care models. This study will produce:

A theoretically informed, empirically evidenced, model of how prescribing and medication use, as a complex multistep process involving multiple people, occurs in a ‘typical’ English local healthcare economy.

Understanding of underlying themes and contributing factors to challenges in the system.

Identification of forms of collaborative action in prescribing and medication use.

Recommendations for system quality indicators.

A toolkit for patients and carers to empower them in conversations with professionals, and for professionals to assess the current processes for prescription medications in their local context. Scrutinising prescribing and medication use practices by applying our model may reduce the need for unanticipated care provision and decrease patient/carer burdens.

Dissemination

Findings will be disseminated through academic publications, a stakeholder dissemination event and a Plain English report circulated to policymakers, commissioners, clinicians, researchers and the public. We will seek informed consent for data archiving and use for secondary research purposes including sharing anonymised data with other researchers.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @sally_anne_fran, @AKajamaa

Contributors: BDF, MO, AK and KM coproduced the study design from inception led by SY, making substantive contributions to gaining funding, ethical approval, and writing this protocol. S-AF was recruited to join the research team once funding was secured, making substantive contributions to refining the study design and writing this protocol. All authors have approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by a Marie Curie Research Grant [MC-19-904] and sponsored by University College London.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Smith J. Building a safer NHS for patients: improving medication safety. London: department of health, 2004. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4084961.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis PJ, Dornan T, Taylor D, et al. Prevalence, incidence and nature of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf 2009;32:379–89. 10.2165/00002018-200932050-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross S, Hamilton L, Ryan C, et al. Who makes prescribing decisions in hospital inpatients? an observational study. Postgrad Med J 2012;88:507–10. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross S, Ryan C, Duncan EM, et al. Perceived causes of prescribing errors by junior doctors in hospital inpatients: a study from the protect programme. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:97–102. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tully MP, Ashcroft DM, Dornan T, et al. The causes of and factors associated with prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf 2009;32:819–36. 10.2165/11316560-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan N, Mattick K. A systematic review of educational interventions to change behaviour of prescribers in hospital settings, with a particular emphasis on new prescribers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;75:359–72. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04397.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, et al. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;359:1373–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodward HI, Mytton OT, Lemer C, et al. What have we learned about interventions to reduce medical errors? Annu Rev Public Health 2010;31:479–97. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yardley I, Yardley S, Williams H, et al. Patient safety in palliative care: a mixed-methods study of reports to a national database of serious incidents. Palliat Med 2018;32:1353–62. 10.1177/0269216318776846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kajamaa A, Mattick K, Parker H, et al. Trainee doctors' experiences of common problems in the antibiotic prescribing process: an activity theory analysis of narrative data from UK hospitals. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028733. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowers B, Ryan R, Kuhn I, et al. Anticipatory prescribing of injectable medications for adults at the end of life in the community: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2019;33:160–77. 10.1177/0269216318815796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engeström Y. Innovative learning in work teams: Analysing cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In: Engeström Y, Miettinen R, Punämaki E, eds. Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: CUP, 1999: 377–406. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engeström Y. Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work 2001;14:133–56. 10.1080/13639080020028747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kajamaa A, Hilli A, Initiatives Clients’. Clients' initiatives and caregivers' responses in the organizational dynamics of care delivery. Qual Health Res 2014;24:18–32. 10.1177/1049732313514138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engeström Y, Kajamaa A, Nummijoki J. Double stimulation in everyday work: critical encounters between home care workers and their elderly clients. Learn Cult Soc Interact 2015;4:48–61. 10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kajamaa A. Unraveling the helix of change: an activity-theoretical study of healthcare change efforts and their consequences. [Doctoral Thesis]. Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki 2010. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-10-6990-1 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campling N, Richardson A, Mulvey M, et al. Self-Management support at the end of life: patients', carers' and professionals' perspectives on managing medicines. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;76:45–54. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latter S, Campling N, Birtwistle J, et al. Supporting patient access to medicines in community palliative care: on-line survey of health professionals' practice, perceived effectiveness and influencing factors. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:148. 10.1186/s12904-020-00649-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowers B, Redsell SA. A qualitative study of community nurses' decision-making around the anticipatory prescribing of end-of-life medications. J Adv Nurs 2017;73:2385–94. 10.1111/jan.13319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abuzour AS, Lewis PJ, Tully MP. Practice makes perfect: a systematic review of the expertise development of pharmacist and nurse independent prescribers in the United Kingdom. Res Social Adm Pharm 2018;14:6–17. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charani E, Castro-Sanchez E, Sevdalis N, et al. Understanding the determinants of antimicrobial prescribing within hospitals: the role of "prescribing etiquette". Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:188–96. 10.1093/cid/cit212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papoutsi C, Mattick K, Pearson M, et al. Social and professional influences on antimicrobial prescribing for doctors-in-training: a realist review. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72:2418–30. 10.1093/jac/dkx194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broom A, Broom J, Kirby E. Cultures of resistance? A Bourdieusian analysis of doctors' antibiotic prescribing. Soc Sci Med 2014;110:81–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLellan L, Yardley S, Norris B, et al. Preparing to prescribe: how do clerkship students learn in the midst of complexity? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2015;20:1339–54. 10.1007/s10459-015-9606-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLellan L, Dornan T, Newton P, et al. Pharmacist-Led feedback workshops increase appropriate prescribing of antimicrobials. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:1415–25. 10.1093/jac/dkv482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noble C, Brazil V, Teasdale T, et al. Developing junior doctors' prescribing practices through collaborative practice: sustaining and transforming the practice of communities. J Interprof Care 2017;31:263–72. 10.1080/13561820.2016.1254164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis PJ, Tully MP. Uncomfortable prescribing decisions in hospitals: the impact of teamwork. J R Soc Med 2009;102:481–8. 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noble C, Billett S. Learning to prescribe through co-working: junior doctors, pharmacists and consultants. Med Educ 2017;51:442–51. 10.1111/medu.13227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute of Clinical Excellence . Palliative care for adults: strong opioids for pain relief. London: NICE, 2012. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg140 [Accessed 6 December 2018].

- 30.Carduff E, Johnston S, Winstanley C, et al. What does 'complex' mean in palliative care? Triangulating qualitative findings from 3 settings. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:12. 10.1186/s12904-017-0259-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan-Woolley B, McHugh G, Luker K. Exploring the views of nurse prescribing among Macmillan nurses. Br J Community Nurs 2008;13:171–7. 10.12968/bjcn.2008.13.4.29026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dietz I, Plog A, Jox RJ, et al. "Please describe from your point of view a typical case of an error in palliative care": Qualitative data from an exploratory cross-sectional survey study among palliative care professionals. J Palliat Med 2014;17:331–7. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson E, Caswell G, Turner N, et al. Managing medicines for patients dying at home: a review of family caregivers' experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:962–74. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson E, Caswell G, Pollock K. The 'work' of managing medications when someone is seriously ill and dying at home: A longitudinal qualitative case study of patient and family perspectives'. Palliat Med 2021;35:1941–50. 10.1177/02692163211030113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Personal correspondence to authors from Marie Curie research Committee. during grant application process. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engeström Y. In Routledge Handbook of the medical humanities 2019 London; Routledge. Available: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781351241779-4/medical-work-transition-yrj%C3%B6-engestr%C3%B6m [Accessed 26 January 2022].

- 37.Pollock K, Wilson E, Caswell G. Managing medicines for patients with serious illness being cared for at home. Available: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/ncare/projects/managing-medicines-for-patients-with-serious-illnessbeing-cared-for-at-home.aspx [Accessed 17 Jun 2019].

- 38.Campling N. Accessing medicines at end-of-life: an evaluation of service provision. Available: http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN12762104 [Accessed 17 Jun 2019].

- 39.Anderson JE, Ross AJ, Jayep, Resilient Health Care . Modelling Resilience and Researching the Gap between Work-as-Imagined and Work—as-done. In: Braithwaite J, Wears RL, Hollnagel E, eds. Reconciling work-as-imagined and work-as-done. 3. Florida: CRC Press p, 2016: 133–42. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kozulin A, Chaiklin S, Karpov Y, et al. Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 269. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kajamaa A. Expanding care pathways: towards interplay of multiple care‐objects. International Journal of Public Sector Management 2010;23:392–402. 10.1108/09513551011047288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engeström Y, Kajamaa A, Kerosuo H. Process Enhancement Versus Community Building: Transcending the Dichotomy through Expansive Learning. In: Yamazumi K, ed. Activity theory and fostering learning: developmental interventions in education and work. Osaka: Center for Human Activity Theory, Kansai University, 2010: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 edition / supplement: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. Adelaide, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute 2015. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 44.James Lind alliance palliative and end-of-life care priority setting partnership. Available: https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/palliative-and-end-of-life-care/ [Accessed 26 Jan 2022].

- 45.Ajjawi R, Rees C, Monrouxe LV. Learning clinical skills during bedside teaching encounters in general practice. J Workplace Learn 2015;27:298–314. 10.1108/JWL-05-2014-0035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsen DP, Wesevich A, Lichtenfeld J, et al. Tying knots: an activity theory analysis of student learning goals in clinical education. Med Educ 2017;51:687–98. 10.1111/medu.13295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skipper M, Musaeus P, Nøhr SB. The paediatric change laboratory: optimising postgraduate learning in the outpatient clinic. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:42. 10.1186/s12909-016-0563-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI manual for evidence synthesis, JBI, 2020. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elyan J, Francis S-A, Yardley S. Understanding the potential for pharmacy expertise in palliative care: the value of stakeholder engagement in a theoretically driven mapping process for research. Pharmacy 2021;9. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9040192. [Epub ahead of print: 26 Nov 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cottrell E, Yardley S. Lived experiences of multimorbidity: an interpretative meta-synthesis of patients', general practitioners' and trainees' perceptions. Chronic Illn 2015;11:279–303. 10.1177/1742395315574764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rashid M, Hodgson CS, Luig T. Ten tips for conducting focused ethnography in medical education research. Med Educ Online 2019;24:1. 10.1080/10872981.2019.1624133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061754supp001.pdf (187KB, pdf)