Abstract

Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang (Diptera: Sciaridae), the Chinese chive root maggot, is a destructive pest of Allium vegetables and flowers that causes severe losses in northern China. Novel biological control technologies are needed for controlling this pest. We identified a new entomopathogenic fungus isolated from infected B. odoriphaga larvae and evaluated the susceptibility of the biological stages of B. odoriphaga and the effects of temperature on fungus growth and pathogenicity. Based on morphological characteristics and molecular phylogeny, the fungus was identified as Mucor hiemalis BO-1 (Mucorales: Mucorales). This fungus had the strongest virulence to B. odoriphaga larvae followed by eggs and pupae, while B. odoriphaga adults were not susceptible. A temperature range of 18–28°C was optimum for the growth and sporulation of M. hiemalis BO-1 and virulence to B. odoriphaga larvae. At 3 and 5 d after inoculation with 105 spores/ml at 23°C, the survival rates were 24.8% and 4.8% (2nd instar larvae), respectively, and 49.6% and 12.8% (4th instar larvae), respectively. The potted plant trials confirmed that M. hiemalis BO-1 exerted excellent control efficiency against B. odoriphaga larvae, and the control exceeded 80% within 5 d when the spore concentration applied exceeded 107 spores/ml. In conclusion, these findings supported the hypotheses that this fungus could serve as an effective control agent against B. odoriphaga larvae and is worth being further tested to determine its full potential as a biocontrol agent.

Keywords: entomopathogenic fungi, Bradysia odoriphaga, biocontrol agent, pathogenicity bioassay, control efficiency

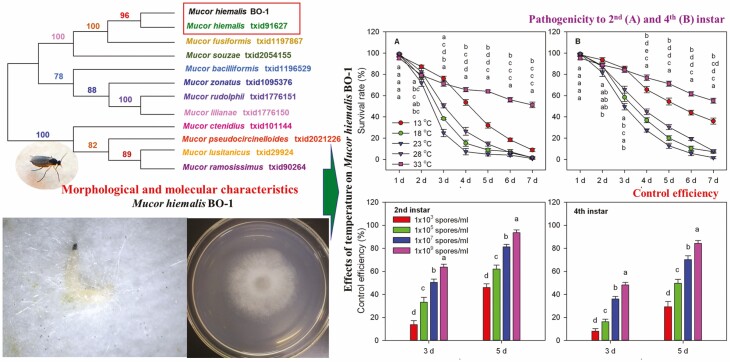

Graphical Abstract

Biological control is an important component of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), owing to its reduced impact on the environment and its substantial efficacy (Shah et al. 2003, Hajek et al. 2007). The biological control agents of pests include predators, parasitic insects, entomopathogenic fungi, entomopathogenic bacteria, insect viruses, and entomopathogenic nematodes (Lacey et al. 2001). Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) comprise a diverse group that includes potential biocontrol agents of many destructive pest species (Bale et al. 2008, Gabarty et al. 2012). Several entomopathogenic fungi have been used for pest control, including Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo), Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschnikoff), Nomuraea rileyi (Farlow), Verticillium lecanii (Zimmerman), and Paecilomyces fumosoroseus (Wize) (Coombes et al. 2016). However, despite the great variety of entomopathogenic fungi, only a few species have been successfully developed as biopesticides. Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae are potential candidates for the biological control of many agricultural pests, such as Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, and Diptera (Kassa et al. 2004, Khoury et al. 2019).

Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang (Diptera: Sciaridae), the Chinese chive root maggot, is a serious pest of Allium vegetables and oramental flowers in northern China (Yang and Zhang 1985, Xue et al. 2005). The larvae tend to aggregate in fields and directly damage plants by feeding on root and corm tissues, resulting in wilt or rot (Zhang et al. 2016). Since the damage caused by B. odoriphaga larvae is cryptic and primarily occurs on the underground portions of plants, it is difficult to effectively control (Zhu et al. 2017, Shi et al. 2018). To date, the most common management practice for B. odoriphaga larvae is applications of organophosphates, carbamates, and neonicotinoid insecticides (Ma et al. 2013). However, after many years of treatments, larvae have developed resistance to pesticides, and this has resulted in unsatisfactory control (Bai et al. 2016a). In addition, conventional chemical pesticide use has been increasingly restricted due to environmental pollution and human health concerns (Shan et al. 2020). Therefore, exploring biological control resources is important for reducing pesticide applications, decreasing environmental pollution, and improving pest population management.

Previous studies reported that compared to other agricultural pests, there are few applicable biological control agents of B. odoriphaga. These include Beauveria bassiana (entomopathogenic fungus), Bacillus thuringiensis (entomopathogenic bacteria), Stratiolaelaps scimitus (predatory mite), and Steinernema feltiae (entomopathogenic nematodes) (Chen et al. 2016, Zhou et al. 2014). Song et al. (2016) isolated a Beauveria thuringiensis strain JQ23 from soil, possessing high insecticidal activity against B. odoriphaga. This strain had a 72 hr LC50 of 8.38 × 106 spore/ml against 2nd instar larvae. Only Beauveria bassiana, Bacillus thuringiensis, and entomopathogenic nematodes have been applied to control B. odoriphaga in the field (Chen et al. 2016). Zhou et al. (2014) reported that when the dosage of Beauveria bassiana granules (15 billion spore/g) was 4.5 kg/ha, the field control efficiency was 81.15% (7 d after application) and 85.19% (21 d after application). Although many entomopathogenic fungi possess good pathogenicity in the laboratory, their field efficacy depends on favorable environmental conditions, such as temperature, humidity, and characteristics of the microorganism (Ekesi et al. 1999, Fargues et al. 2003). For example, most entomopathogenic fungi exert good pathogenicity at optimum temperatures (Mwamburi et al. 2015), and the optimum temperatures of Beauveria bassiana that provided the best control efficiency ranged from 25 to 30°C (Fargues et al. 1997, Shimazu 2004). Bradysia odoriphaga is an underground insect in its immature stages and adults leave the soil. However, during the emergence peak of B. odoriphaga, the mean soil temperature in fields is typically below 20°C, which is not optimal for many biological insecticides (Shi et al. 2020). To sum up, finding an entomopathogenic fungus possessing high pathogenicity and broad environmental adaptability for use against B. odoriphaga appears to be key to improving biocontrol efficiency.

The genus Mucor includes many species of filamentous fungi widely distributed in soil that are usually associated with abundant humus. Most species are saprotrophic and widely applied in fermentation processes. Individual Mucor species are well known as pathogens of animals and humans, although there are a few Mucor species reported as insect pathogens. Reiss et al. (1993) reported that some Mucor hiemalis strains were pathogenic to Artemia salina, an important arthropod. Konstantopoulou and Mazomenos (2005) isolated six species of entomopathogenic fungi from diseased Bactrocera oleae and Sesamia nonagrioides. Bioassays revealed that two strains of M. hiemalis were pathogenic to Ceratitis capitata larvae causing more than 80% mortality. This is the only report concerning the pathogenicity of M. hiemalis to Diptera.

In 2019, we isolated one strain of entomopathogenic fungi from infested B. odoriphaga larvae collected from a Chinese chive field. Morphological observation indicated that this strain was a Mucor species. In the process of culture, this strain was strongly pathogenic and infectious, causing laboratory population extinction within a few days once spore transmission spread occurred. We suspected that this entomopathogenic fungus had the potential for development as a biocontrol agent.

In this study, we identified the isolate from infected B. odoriphaga larvae using morphological and molecular analyses. The susceptibility of the life stages of B. odoriphaga to this entomopathogenic strain and the effects of temperatures on fungus growth and pathogenicity were evaluated. Additionally, the control efficiency was also conducted by a potted plant trial. Our results provide a new biological control agent for application in B. odoriphaga control and increase available options for exploring the green control techniques for crop root maggots.

Materials and Methods

Insect Materials

Samples of B. odoriphaga larvae were originally collected from a Chinese chive field in Tai’an, Shangdong, in April 2015. The samples were maintained at the College of Agronomy, Liaocheng University, and reared on Chinese chives for more than 10 generations using the method described by Xue et al. (2005). Eggs, larvae, and pupae were reared in culture dishes (Φ = 9 cm), and pairs of newly emerged adults were placed in plastic oviposition containers (3 cm diameter × 1.5 cm high). Colonies were maintained in growth cabinets at 23 ± 1°C with 75 ± 5% relative humidity.

Entomopathogenic Fungi Isolated From Infested Larvae

Infested B. odoriphaga larvae were collected in winter from Chinese chives field in Liaocheng, Shangdong (N 36.784, E 115.447, 10 November 2019). According to the method described by Barra et al. (2013), all symptomatic B. odoriphaga larvae with signs of fungal infection were surface sterilized with a 1% sodium hydrochloride solution dip for 1 min. Subsequently larvae were washed three times with distilled water and placed on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plates (Φ = 9 cm). Plates were incubated at 23°C for 3 d to obtain growth of mycelia occurring internally, and the hypha at the edge of the colony was picked and transferred to new PDA plates to obtain a pure strain.

Identification of Entomopathogenic Fungi Isolates

Morphological Description

The pure entomopathogenic fungus strain was incubated at 23°C, and the microscopic features (morphology of hyphae, fruiting bodies, and spores) and macroscopic features (colony morphology and color) were examined by microscopic observation methods described by Nyongesa et al. (2015) andGerald (1995).

Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis

DNA from a fungal isolate was extracted using an EasyPure Fungi Genomic DNA Kit (ComWin Biotech, Beijing, China). Sequences containing the region encoding ITS was PCR amplified with primers described by Hinrikson et al. (2005) (ITS4: 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′, ITS5:5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′). The fungal DNA was sequenced by BioSune Limited Company (Shanghai, China). Resulting ITS sequences were aligned using ClustalW in Mega v. 6.0, and their homologies were determined by BLAST searches within the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database. A phylogenetic tree of the isolate was constructed using model strains of genus Mucor hiemalis (Taxonomy ID: 91627, Accession: NR_152948.1), Mucor fusiformis (Taxonomy ID: 1197867, Accession: NR_111660.1), Mucor souzae (Taxonomy ID: 2054155, Accession: NR_165210.1), Mucor bacilliformis (Taxonomy ID: 1196529, Accession: NR_145285), Mucor zonatus (Taxonomy ID: 1095376, Accession: NR_103638), Mucor rudolphii (Taxonomy ID: 1776151, Accession: NR_152977), Mucor lilianae (Taxonomy ID: 1776150, Accession: NR_152978), Mucor ctenidius (Taxonomy ID: 101144, Accession: NR_168144), Mucor pseudocircinelloides (Taxonomy ID: 2021226, Accession: NR_169896), Mucor lusitanicus (Taxonomy ID: 29924, Accession: NR_126127), and Mucor ramosissimus (Taxonomy ID: 90264, Accession: NR_103627). This phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA v7.0, by the neighbor-joining method.

Effects of Environmental Temperatures on Fungus Growth

Pure fungal isolate agar disks (Φ = 8 mm) containing mycelium were made by a fungal puncher from the edge of the pure colony. Every agar disk was placed upside down at the center of a PDA plate (Φ = 9 cm). The plates were incubated in growth chambers at different temperatures (13, 18, 23, 28, and 33°C) according to a study on the effects of temperature gradients on B. odoriphaga (Li et al. 2015). At 23°C temperature was used as the control. Every temperature treatment contained five plates (replicates). The colony diameter was recorded daily using the cross-bonded method. Colony growth was recorded as mean perpendicular radius minus the diameter of the inoculum plug. After 10 d, the spore suspension of every plate was prepared using 50 ml 0.1% Tween 80 distilled water according to the description by Mwamburi et al. (2015), and the spore suspension concentration was calculated with blood counting chamber analysis.

Pathogenicity Bioassays

Pathogenicity to Biological Stages of B. odoriphaga

Serial spore suspension dilutions (1 × 103, 1 × 105, and 1 × 107 spores/ml) were made with 0.1% Tween 80 distilled water. Eggs, 2nd and 4th instar larvae, pupae, and adults were used as the test subjects. Bioassays on 2nd and 4th instar larvae (within 1 d after molt) were conducted using standard contact and stomach bioassay methods with slight modifications (Zhang et al. 2016). One piece of filter paper (Φ = 9 cm) was moistened by dropping 1 ml of spore suspension and placed in a culture dish, and fresh diet (fresh Chinese chives) was placed on the filter paper. Larvae were placed around the fresh diets. Eggs, pupae, and adults were reared in culture dishes (Φ = 9 cm) covered with filter paper moisturized by 1 ml spore suspension. This bioassay was conducted at 23°C, and pure water treatment was used as the control. Each treatment (concentration) contained five replicates and each replicate contained 20 individuals. B. odoriphaga mortality was recorded daily.

Pathogenicity Under Different Temperatures

According to the results of pathogenicity to biological stages, spore suspension (1 × 105 spores/ml) possessing moderate pathogenicity to B. odoriphaga larvae was chosen as the test dosage. The spore suspensions (1 × 105 spores/ml) were made with 0.1% Tween 80 distilled water. Bioassays on 2nd and 4th instar larvae were conducted using a previously described method. The culture dishes after adding spore suspension and test larvae were transferred to different temperature conditions (13, 18, 23, 28, and 33°C). Each treatment contained five replicates and each replicate contained 20 individuals. Larval survival was recorded daily for 7 d.

Trials with Potted Plants

Serial spore suspension dilutions (1 × 103, 1 × 105, 1 × 107, and 1 × 109 spores/ml) were made with 0.1% Tween 80 distilled water. The 2nd and 4th instar larvae of B. odoriphaga were used as the test subjects. Potted Chinese chives (Xuejiu Variety) planted for two years were prepared. Pots with no larval damage were chosen as the experimental material. Before the trial, the aboveground part of Chinese chives was cut off and 2nd or 4th instar larvae were transferred into the rhizosphere soil. On the day of the experiment, 25 ml of spore suspension was added to the soil of every pot. Pure water (without spores) treatment was used as the control. Each treatment contained five replicates and each replicate contained 40 individuals. During the experiment, adequate water was added daily to maintain soil moisture. All the pots were maintained in growth chambers at 23 ± 1°C with 75 ± 5% relative humidity, and a 12:12 hr light: dark cycle. On the 3rd and 5th day after treatment, the larval survival of B. odoriphaga was recorded. The control efficiency was calculated according to Equations (1) and (2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistics software (Version 19.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Values in the heat hardening treatments were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison test (P < 0.05).

Results

Morphological and Molecular Characteristics

Macroscopic Morphological Analysis

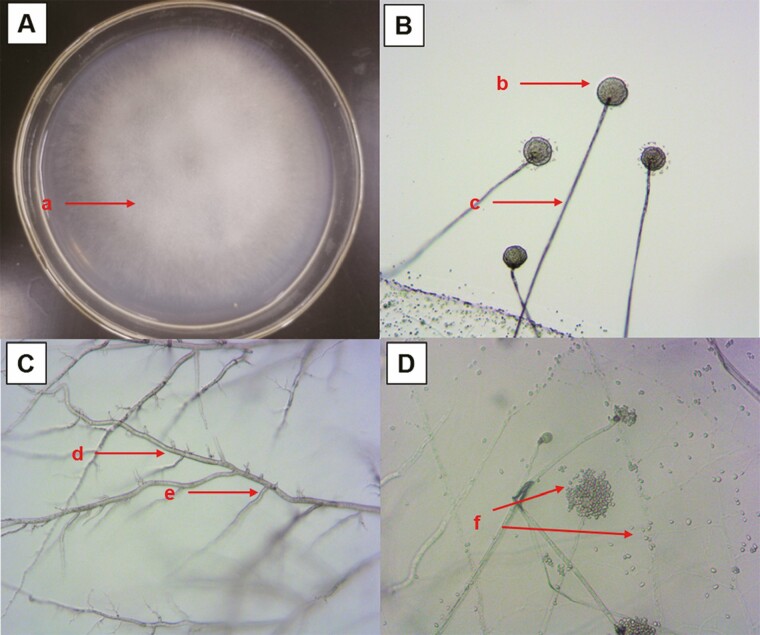

This entomopathogenic fungi colonies cultured on PDA were white and slightly transparent, covered with thick long pile like cotton on the side and a rough surface (aerial hyphae) (Fig. 1A). According to the description by Gerald (1995), small black dots (sporangium) were borne on the tip of the mycelium (Fig. 1A). Microscopic characterization of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 using an optical microscope showed that the hyphae were smooth, aseptate, and polynuclear (Fig. 1C). The sporangiospores were globose to subglobose with smooth outer walls and wrapped in the sporangia (Fig. 1D), which were subglobose and at the top of individual aseptate hyphae (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Macroscopic morphological characteristics of Mucor hiemalis BO-1. A (a) white and slightly transparent aerial hyphae on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium; B (b) small black sporangium; (c) vertical and uniramous sporangiophore; C (d) smooth, aseptate and polynuclear hyphae; (e) branched hyphae; D (f) broken sporangium releasing sporangiospores.

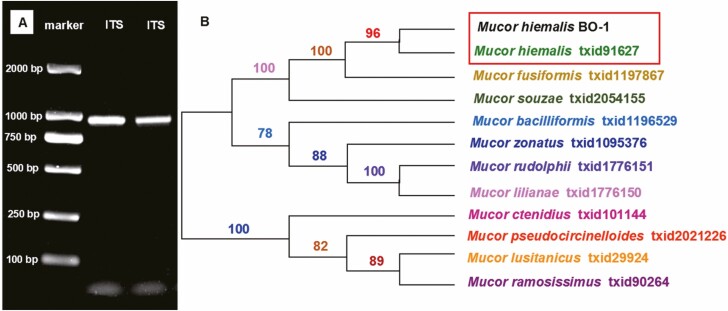

Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of ITS Region

The ITS rDNA region of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 was amplified and sequenced. The length of the ITS sequence was 936 bp and it was deposited in the GenBank database (accession number MN686205). The sequence similarity search using ITS sequences of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 in BLASTN program revealed that this strain and Mucor hiemalis (CBS201.65) were present in the same cluster with 96% sequence similarity, which were well supported by a bootstrap value of 100% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree based on the analysis of partial ITS sequences of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 and other Mucor species. A, The electrophoretic band of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 partial ITS sequence. B, neighbor-joining tree.

Pathogenicity of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 Against B. odoriphaga Larvae

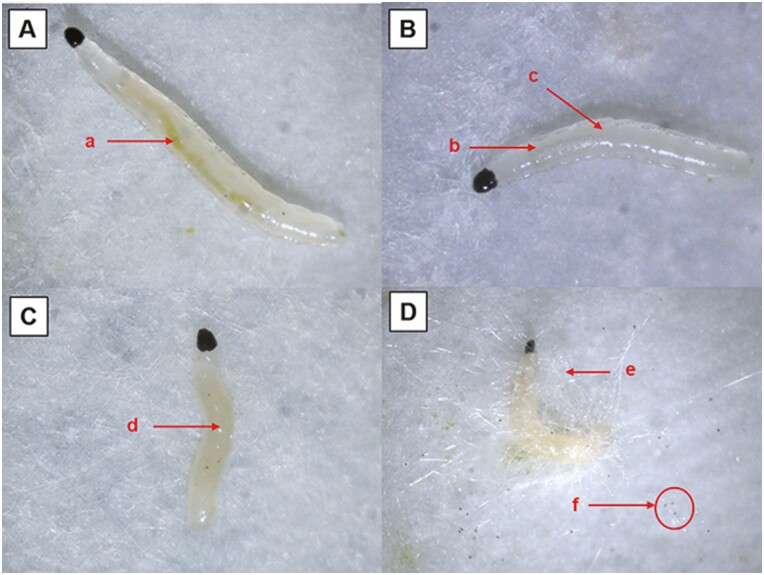

A total of 100 B. odoriphaga larvae treated with Mucor hiemalis BO-1 (1.0 × 106 spores/ml) were raised in moist petri dishes and observed with a stereoscopic microscope. In the early stages of infection (24 hr after inoculation), the larval movement became slower. Few food particles were present in larval guts (Fig. 3A). In the mid-course of pathogenesis (48 hr after inoculation), larval behavior was more sluggish, and the larvae barely moved even after being touched by brush. The larval body became transparent gradually. At 48 hr, the larval feeding capacity was maintained, but the food consumption declined dramatically and only a small amount of diet material was seen in the digestive tract (Fig. 3B). At the end of pathogenesis (72 hr after inoculation), the larvae were moribund (only the head and mouthparts moved slightly) and the body was yellow, turbid, and supple (Fig. 3C). In the growth period of the hyphae (120 hr after inoculation), numerous white aerial hyphae grew from the dead larval body, and black sporangia were present at the top of the mycelium (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Pathogenesis of B. odoriphaga larvae infected by Mucor hiemalis BO-1. A 24 hr after inoculation; (a) green food particles were present in larval guts; B 48 hr after inoculation; (b) few food particles were present in larval guts; (c) the body gradually became transparent and bright; C 72 hr after inoculation; (d) yellow, turbid and supple larval body; D 120 hr after inoculation; (e) numerous white aerial hyphae grew from the dead larval body; (f) black sporangia at the top of the mycelium.

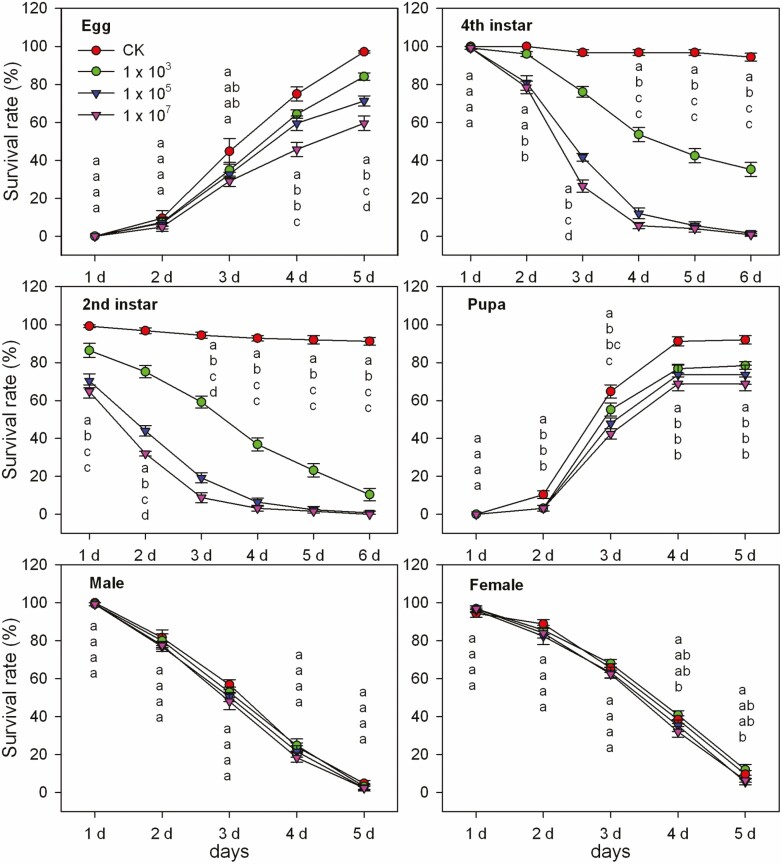

Pathogenicity of M. hiemalis BO-1 to Biological Stages of B. odoriphaga

We observed the infection of M. hiemalis BO-1 on different stages of B. odoriphaga, and the bioassay results indicated that M. hiemalis BO-1 was more pathogenic effect to B. odoriphaga larvae than to eggs, pupae, and adults (Fig. 4). For 2nd instar larvae, the survival rates after inoculation decreased to 75.2% (103 spores/ml), 44% (105 spores/ml), and 32% (107 spores/ml), while that of the control was 96.8%. With the extension of time, the survival rates are declined rapidly. At 4 d after inoculation, the survival rates were 36.8% (103 spores/ml), 6.4% (105 spores/ml), and 3.2% (107 spores/ml). The 4th instar larvae were less susceptible to M. hiemalis BO-1 than the 2nd instar larvae. At 4 d and 5 d after treatment, the survival rates were 53.6% and 42.4% (103 spores/ml), respectively, 12% and 5.6% (105 spores/ml), respectively, and 5.6% and 4% (107 spores/ml), respectively. These rates were higher than those of the 2nd instar larvae.

Fig. 4.

Pathogenic effects of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 on different stages of Bradysia odoriphaga. Data in the figure are the mean ± SE. Different letters over the same column indicate significant differences between different spore concentration treatments at the P < 0.05 level as indicated by one-way ANOVA.

M. hiemalis BO-1 showed only slight pathogenicity to B. odoriphaga eggs and pupae. At 5 d after treatment, the egg hatchability was 84.12% (103 spores/ml), 71.29% (105 spores/ml), and 59.51% (107 spores/ml), and most newly hatched larvae died within 1 d. The adult emergence rates were 78.4% (103 spores/ml), 73.6% (105 spores/ml), and 68.8% (107 spores/ml). B. odoriphaga adults were scarcely affected based on no significant differences in longevity among the different treatments.

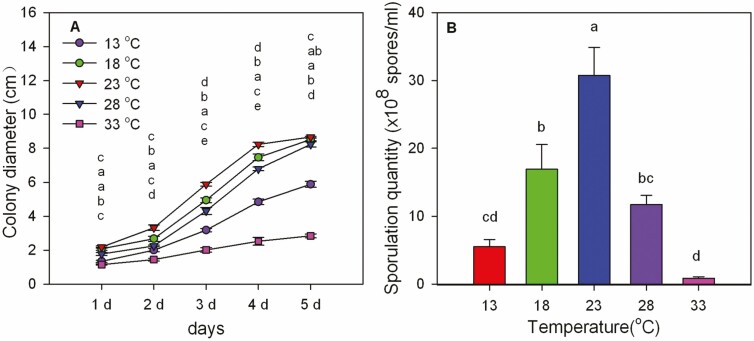

Effects of Temperature on the Growth and Pathogenicity of Mucor hiemalis BO-1

Fungus Growth

The culture results showed that the growth and sporulation quantity of M. hiemalis BO-1 were affected by temperature (Fig. 5). Temperatures ranging from 18 to 28°C were beneficial to mycelial growth, while the mycelium grew poorly at 33°C (Fig. 5A). After 5 d culture, the colony diameter was 5.83 cm (13°C), 8.52 cm (18°C), 8.66 cm (23°C), 8.23 cm (28°C), and 2.84 cm (33°C) (F4,20 = 398.397, P < 0.001). After 10 d culture, the sporulation quantities were 5.5 × 108 spores/ml (13°C), 1.69 × 109 spores/ml (18°C), 3.07 × 109 spores/ml (23°C), 1.17 × 109 spores/ml (28°C), and 0.86 × 108 spores/ml (33°C), and there were significant differences between different treatments (F4,20 = 19.969, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5B). We found that 23°C was the optimum temperature for growth and sporulation of M. hiemalis.

Fig. 5.

Effects of temperature on mycelial growth (A) and conidiation (B) of Mucor hiemalis BO-1. Data in the figure is the mean ± SE. Different letters over the same column from the top indicate significant differences between different temperature treatments at the P < 0.05 level as indicated by one-way ANOVA.

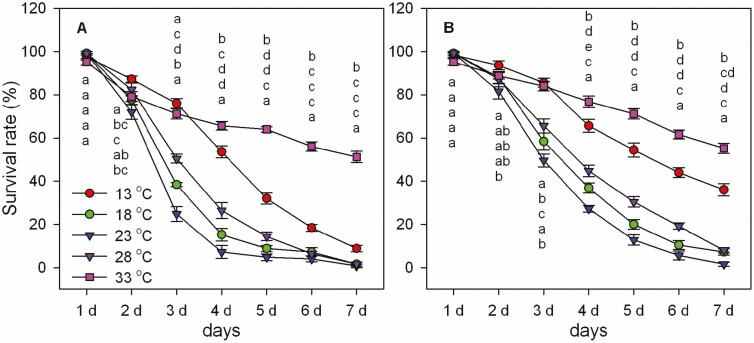

Pathogenicity

The bioassay results indicated that the temperature affected the pathogenicity of M. hiemalis BO-1 to B. odoriphaga larvae and temperatures ranging from 18 to 28°C were the most effective for M. hiemalis BO-1 (Fig. 6). For 2nd instar larvae, at 3 d after inoculation with 105 spores/ml, the survival rates were 38.4% (18°C), 24.8% (23°C), and 50.4% (28°C). These rates were significantly lower than survival at 13°C (76%) and 33°C (71.2%). For 4th instar larvae, at 3 d after inoculation with 105 spores/ml, the survival rates were 58.4% (18°C), 49.6% (23°C), and 65.6% (28°C). These were significantly lower than survival rates at 13°C (85.6%) and 33°C (84%). At 5 d after inoculation, a similar data trend was observed. The relatively high 33°C temperature might suppress the pathogenicity of M. hiemalis BO-1. The survival rates were still 55.2% (4th instar) and 51.2% (2nd instar) until 7 d, and the mortality might have been affected by high temperature. The optimum temperature for the pathogenicity of M. hiemalis BO-1 was 23°C followed by 18°C and 28°C.

Fig. 6.

Effects of environmental temperatures on the pathogenicity of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 to Bradysia odoriphaga 2nd (A) and 4th (B) instar larvae. Data in the table are the mean ± SE. Different letters over the same column from the top indicate significant differences between different temperature treatments at the P < 0.05 level as indicated by one-way ANOVA.

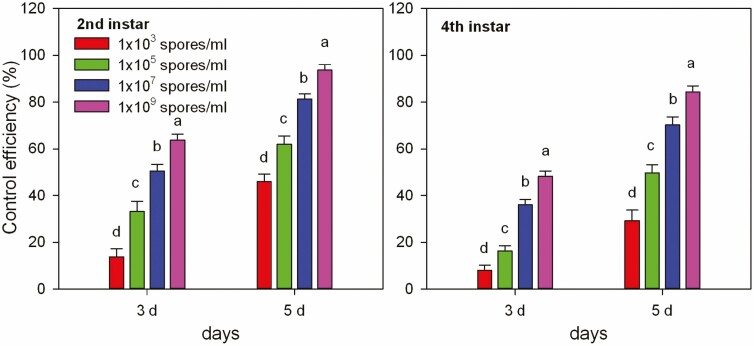

Results of Potted Plant Trials

M. hiemalis BO-1 provided superior control of B. odoriphaga 2nd and 4th instar larvae when the spore suspension concentration exceeded 107 spores/ml. At 3 d after the 2nd instar larvae treatment, the control efficiencies were 33.16% (1 × 105 spores/ml), 50.51% (1 × 107 spores/ml), and 63.77% (1 × 109 spores/ml) (Fig. 7). For 4th instar larvae, the control efficiencies were 16.25% (1 × 105 spores/ml), 36.04% (1 × 107 spores/ml), and 48.22% (1 × 109 spores/ml), respectively. At 5 d after the 2nd instar larvae treatment, the control efficiencies were 45.99% (1 × 103 spores/ml), 62.03% (1 × 105 spores/ml), 81.28% (1 × 107 spores/ml), and 93.58% (1 × 109 spores/ml), respectively (Fig. 7). For 4th instar larvae, the control efficiencies were 29.32% (1 × 103 spores/ml), 49.74% (1 × 105 spores/ml), 70.16% (1 × 107 spores/ml), and 84.29% (1 × 109 spores/ml), respectively.

Fig. 7.

Control efficacy of Mucor hiemalis BO-1 against Bradysia odoriphaga 2nd and 4th instar larvae. Data in the table are the mean ± SE. Different letters over the same column from the top indicate significant differences between different treatments at the P < 0.05 level as indicated by one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

In this study, we isolated a new entomopathogenic fungus strain from infested B. odoriphaga larvae. Based on morphological and molecular characters, this strain was identified as Mucor hiemalis. The unique morphological features of this strain include white colonies covered with fluffy mycelia and globose sporangia on the tips of the mycelium. These features revealed that this isolate was Mucor hiemalis (Zhang et al. 2018). Molecular identification (ITS sequence analysis) with supplementary elements was performed to confirm the identification (Ardeshir et al. 2016). Reiss et al. (1993) reported the pathogenicity of 15 species of Mucorales (including M. hiemalis) to brine shrimp (Artemia salina) larvae, andBibbs et al. (2013) reported that a new stain of Mucor fragilis Bainier had strong pathogenicity to brown widow spiders (Latrodectus geometricus Koch). Therefore, this entomopathogenic fungi strain was named Mucor hiemalis BO-1.

Biological assays revealed that Mucor hiemalis BO-1 had a substantial pathogenic effect on B. odoriphaga larvae. After infection, B. odoriphaga larval movement slowed, and the insect body became transparent. During infection, food residue in the alimentary canal decreased. Therefore, it appears that Mucor hiemalis BO-1 infection disrupted the physiological and digestive functions of B. odoriphaga because of nutritional plunder, degrading enzymes, and toxic proteins. Previous studies have reported that Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae produce insecticidal mycotoxins against pests (Sowjanya et al. 2008, Khoury et al. 2019, Yin et al. 2021). Wei et al. (2017) reported that Beauveria bassiana infection resulted in dysbiosis of mosquito gut microbiota and decreasing bacterial diversity, which promoted mortality of the mosquito larvae. Most entomopathogenic fungi gain access to the body cavity through the external cuticle, where they consume nutrients, produce toxins, destroy host cells and eventually kill the hosts (Wang and Wang 2017). A few entomopathogenic fungi invade the body through the digestive tract by direct feeding of insects, where they disrupt larval feeding capacity primarily during the initial stage of pathogenesis (Kubicek and Druzhinina 2007). However, determination of the main infection mode for Mucor hiemalis BO-1 against B. odoriphaga larvae will require additional studies.

Entomopathogenic fungi have been considered as biopesticides because they are an environmentally friendly alternative to chemical insecticides (Shah and Pell 2003, Barra et al. 2013). Clarifying the susceptibility of biological stages of pests to entomopathogenic fungi is crucial for field application and this information be used to effectively target the most damaging insect stages (Shah and Pell 2003,Angel et al. 2005). The susceptibility bioassay results showed that B. odoriphaga larvae are more susceptible to M. hiemalis BO-1 than other life stages, and early-instar larvae are more susceptible than older larvae. In addition, M. hiemalis BO-1 also showed mild pathogenicity to eggs and pupae. At 120 hr after treatment with 107 spores/ml, the survival rate was 59.51% (eggs) and 68.8% (pupae). Although some larvae from treated eggs successfully eclosed, they died within 24 hr. This may have resulted from the strong pathogenicity of M. hiemalis BO-1 to early-instar larvae. However, B. odoriphaga adults were not susceptible to M. hiemalis BO-1. In contrast, Daniel and Wyss (2009) observed higher mortality of Rhagoletis cerasi adults and larvae in contact bioassay for all the fungi (Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, and Isaria fumosorosea) tested as compared to the other life stages, and the adult life span of R. indifferens treated with M. anisopliae was shortened and fertility was reduced. Yee and Lacey (2005) also reported that Rhagoletis indifferens adults were more susceptible to Metarhizium anisopliae than larvae and eggs. These dissimilar results could be caused by differences among the entomopathogenic fungi species, which possess different infection modes, or different types of insect species. In this study, M. hiemalis BO-1 exhibited strong pathogenicity to B. odoriphaga larvae, which is the stage causing the greatest plant damage and economic losses (Zhang et al. 2016).

If an entomopathogenic fungus is used for pest control in the field, it must exert satisfactory insecticidal activity under a variety of environmental conditions (Kubicek and Druzhinina 2007). Temperature is a key constraint restricting the ability and speed of which entomopathogenic fungi to infect and colonize host insects (Fargues et al. 2003, Yeo et al. 2003, Kryukov et al. 2018). Our results confirmed that 18–28°C was the optimum temperature for growth and sporulation of M. hiemalis BO-1. At 13°C and 33°C, growth and sporulation of M. hiemalis BO-1 were reduced in comparison with 23°C. A pathogenicity bioassay confirmed that M. hiemalis BO-1 also possessed stronger pathogenicity against B. odoriphaga larvae at 18–28°C. This agrees with other studies showing little germination and growth of Metarhizium spp at low temperatures (Ekesi et al. 1999, Bai et al. 2016b). The pathogenicity bioassay results were consistent with the biorational assay results. At 13°C M. hiemalis BO-1 exerted a slightly more pathogenic effect than that at 33°C. It is possible that the low temperature merely slowed the pathogenic process of the fungus while the high temperature blocked the pathogenic process. Similarly, Fargues and Luz (2000) and Soyelu et al. (2020) reported that a temperature between 20 and 25°C was optimum for the pathogenicity of B. bassiana against Rhodnius prolixus nymphs and Musca domestica larvae and adults, and the fungal virulence declined rapidly at temperatures exceeding 30°C. This indicated that extreme temperatures not only restricted the growth and infection of the fungus, but also accelerated nutrient metabolism resulting in less extracellular enzymes and toxic proteins (Bai et al. 2016b). Previous studies reported that during the emergence peak of B. odoriphaga larvae, the mean soil temperature fluctuates between 15 and 25°C, which would be suitable for the use of M. hiemalis BO-1 to control B. odoriphaga based on our results (Shi et al. 2018, 2020). To sum up, M. hiemalis BO-1 application could provide satisfactory control efficiency during the spring and autumn in open fields, or during winter in the greenhouse. During these seasons, the soil temperature ranges between 10 and 25°C (Shi et al. 2018). After summer and winter, M. hiemalis BO-1 reapplication could increase the soil abundance of this fungus and increase its efficacy. However, the pathogenicity of entomopathogenic fungi is also dependent on humidity and other abiotic factors. In general, dry conditions and poor nutrition are generally unsuitable for the propagation of fungi (Garrido-Jurado et al. 2011). Further studies on the interactive relationships among temperature, humidity, and the pathogenicity of fungi should be conducted.

Many entomopathogenic fungi exhibit good insecticidal activity in the laboratory, but the field control was unsatisfactory. This performance failure has been attributed to complex natural environment conditions (Hussein et al. 2010, Garrido et al. 2011). We simulated field experiments using potted Chinese chives plants to evaluate the potential of M. hiemalis BO-1 for the control of root maggots. The results confirmed that when the concentration of spore suspension exceeded 1 × 107 spores/ml, the control efficiency was satisfactory. At 5 d after treatment, the control efficiencies were 81.28% (1 × 107 spores/ml) and 93.58% (1 × 109 spores/ml) for 2nd instar larvae, and 70.16% (1 × 107 spores/ml) and 84.29% (1 × 109 spores/ml) for 4th instar larvae. This is an exceptional result compared to other entomopathogenic fungi, which display excellent control efficiency in the field only when the concentration of the spore suspension exceeds 1 × 1011 spores/ml (Zhou et al. 2014, Coombes et al. 2016, Murigu et al. 2016). M. hiemalis BO-1 possessed excellent control efficiency against B. odoriphaga larvae, and control was rapid, with only three 3–5 d being was required to achieve a high level of control. Other biocontrol agents, such as Beauveria bassiana (Zhou et al. 2014), Bacillus thuringiensis (Song et al. 2016) and entomopathogenic nematodes (Wu et al. 2017) require more than 7 d to achieve the same effect. However, combinations with other entomopathogenic fungi or chemical insecticides could provide better control and these should be studied further.

In conclusion, we isolated a new entomopathogenic fungi strain from infested B. odoriphaga larvae. This was identified as Mucor hiemalis BO-1 based on the morphological and molecular characteristics. Bioassay results confirmed that Mucor hiemalis BO-1 exhibited the greatest pathogenicity to B. odoriphaga larvae at 18–28°C, a temperature range that was beneficial to fungal growth and sporulation. A pot experiment confirmed that M. hiemalis BO-1 possessed efficient control efficiency against B. odoriphaga larvae, and control exceeded 80% within 5 d. M. hiemalis BO-1 should be further evaluated for use as a biocontrol agent for B. odoriphaga.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by ‘Shandong provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR201911130528)’ and ‘National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001929)’. We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

The study was jointly conceived by GZ, WD and MX. Experiments were designed by GZ and MX. GZ prepared the manuscript; YZ, MX, WD, ML, and ZL edited the manuscript, and GZ and WD carried out the experiments.

References Cited

- Angel-Sahagún, C., Lezama-Gutiérrez R., Molina-Ochoa J., Galindo-Velasco E., López-Edwards M., Rebolledo-Domínguez O., Cruz-Vázquez C., Reyes-Velázquez W., Skoda S., and Foster J. E.. 2005. Susceptibility of biological stages of the horn fly, Haematobia irritans, to entomopathogenic fungi (Hyphomycetes). J Insect Sci, 5: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardeshir, Z., Mohammadali Z., Mansour B., and Jamal H., . 2016. Molecular identification of Mucor and Lichtheimia species in pure cultures of Zygomycetes. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 9(4): e35237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, G. Y., Xu H., Fu Y. Q., Wang X. Y., Shen G. S., Ma H. K., Feng X., Pan J., Gu X. S., Guo Y. Z., . et al. 2016a. A comparison of novel entomopathogenic nematode application methods for control of the chive gnat, Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 109: 2006–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y., Cui Y., Cao N., Liu Y., Ghulam A., and Wang B., . 2016b. Effects of Luz humidity and temperature on the pathogenecity of Beauveria bassiana against Stephanitis nashi and Locusta migratoria manilensis. Chinese J Biol Control. 32: 735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, J. S., van Lenteren J. C., and Bigler F.. . 2008. Biological control and sustainable food production. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363: 761–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barra, P., Rosso L., Nesci A., and Etcheverry M., . 2013. Isolation and identification of entomopathogenic fungi and their evaluation against Tribolium confusum, Sitophilus zeamais, and Rhyzopertha dominica in stored maize. J. Pest Sci. 86: 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Benny, G. L 1995. Classical morphology in zygomycete taxonomy. Can. J. Bot. 73: S725–S730. [Google Scholar]

- Bibbs, C.S., Vitoreli A.M., Benny G., Harmon C.L., and Baldwin R.W.. 2013. Susceptibility of Latrodectus geometricus (Araneae: Theridiidae) to a Mucor strain discovered in north central Florida, USA. Fla Entomol. 96: 1052–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H., Wang Y., Zhou X., Gao H., Zhai Y., and Yi Y., . 2016. Status and prospect on biological control of Bradysia odoriphaga. Shandong Agric. Sci. 48: 158–161. [Google Scholar]

- Coombes, C.A., Hill M. P., Moore S. D., and Dames J. F., . 2016. Entomopathogenic fungi as control agents of Thaumatotibia leucotreta in citrus orchards: field efficacy and persistence. Biocontrol. 61: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C., and Wyss E., . 2009. Susceptibility of different life stages of the European cherry fruit fly, Rhagoletis cerasi, to entomopathogenic fungi. J. Appl. Entomol. 133:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ekesi, S., Maniania N., and Ampong-Nyarko K., . 1999. Effect of temperature on germination, radial growth and virulence of Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana on Megalurothrips sjostedti. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 9: 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Fargues, J., and Luz C.. . 2000. Effects of fluctuating moisture and temperature regimes on the infection potential of Beauveria bassiana for Rhodnius prolixus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 75: 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargues, J., Goettel M., Smits N., Ouedraogo A., and Rougier M., . 1997. Effect of temperature on vegetative growth of Beauveria bassiana isolates from different origins. Mycologia. 89: 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Fargues, J., Vidal C., Smits N., Rougier M., Boulard T., Mermier M., Nicot P., Reich P., Jeannequin B., and Ridray G., . 2003. Climatic factors on entomopathogenic hyphomycetes infection of Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) in Mediterranean glasshouse tomato. Biol. Control. 28: 320–331. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarty, A., Salem H., Fouda M., Abas A., and Ibrahim A., . 2012. Pathogencity induced by the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in Agrotisipsilon (Hufn.). J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 7: 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Jurado, I., Torrent J., Barron V., and Quesada-Moraga E., 2011. Soil properties affect the availability, movement, and virulence of entomopathogenic fungi conidia against puparia of Ceratitis capitata (Diptera:Tephritidae). Biol. Control. 58: 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek, A.E., McManus M. L., and Junior I. D., . 2007. A review of introductions of pathogens and nematodes for classical biological control of insects and mites. Biol. Control. 41: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrikson, H. P., Hurst S. F., De Aguirre L., and Morrison C. J.. . 2005. Molecular methods for the identification of Aspergillus species. Med. Mycol. 43: S129–S137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, K.A., Abdel-Rahman M., Abdel-Mallek A. Y., El-Maraghy S. S., and Jin H. J.. . 2010. Climatic factors interference with the occurrence of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in cultivated soil. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 9: 7674–7682. [Google Scholar]

- Kassa, A., Stephan D., Vidal S., and Zimmermann G., . 2004. Laboratory and field evaluation of different formulations of Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum submerged spores and aerial conidia for the control of locusts and grasshoppers. Biocontrol. 49: 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, C.A., Guillot J., and Nemer N., . 2019. Lethal activity of beauvericin, a Beauveria bassiana mycotoxin, against the two-spotted spider mites, Tetranychus urticae Koch. J. Appl. Entomol. 143: 974–983. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulou, M.A., and Mazomenos B., . 2005. Evaluation of Beauveria bassiana and B. brongniartii strains and four wild-type fungal species against adults of Bactrocera oleae and Ceratitis capitata. Biocontrol. 50: 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Kryukov, V. Y., Yaroslavtseva O. N., Whitten M. M. A., Tyurin M. V., Ficken K. J., Greig C., Melo N. R., Glupov V. V., Dubovskiy I. M., and Butt T. M.. . 2018. Fungal infection dynamics in response to temperature in the lepidopteran insect Galleria mellonella. Insect Sci. 25: 454–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek, C.P., and Druzhinina I. S.. . 2007. Entomopathogenic fungi and their role in pest control. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey L. A, Frutos R. and Kaya H. K., . 2001. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: do they have a future? Biol. Control. 21: 230–248. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Y. Yang, W. Xie, Q. Wu, B. Xu, S. Wang, Y. Zhang. 2015. Effects of temperature on the age-stage, two-sex life table of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 108(1): 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J., Chen S., Moens M., Han R., and De Clercq P., . 2013. Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) against the chive gnat, Bradysia odoriphaga. J. Pest Sci. 86: 551–561. [Google Scholar]

- Murigu, M. M., Nana P., Waruiru R. M., Nga’nga’ C. J., Ekesi S., and Maniania N. K.. . 2016. Laboratory and field evaluation of entomopathogenic fungi for the control of amitraz-resistant and susceptible strains of Rhipicephalus decoloratus. Vet. Parasitol. 225: 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwamburi, L. A., Laing M. D., and Miller R. M.. . 2015. Effect of surfactants and temperature on germination and vegetative growth of Beauveria bassiana. Braz. J. Microbiol. 46: 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyongesa, B.W., Okoth S., and Ayugi V., . 2015. Identification key for Aspergillus species isolated from maize and soil of Nandi County, Kenya. Adv. Microbiol. 5: 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, J., 1993. Biotoxic activity in the Mucorales. Mycopathologia. 121: 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P. A., and Pell J. K.. . 2003. Entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61: 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, T., Zhang H., Chen C., Chen A., Shi X., and Gao X.. . 2020. Low expression levels of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits Boα1 and Boβ1 are associated with imidacloprid resistance in Bradysia odoriphaga. Pest Manag. Sci. 76: 3038–3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.H., Hu J. R., Wei Q. W., Ya Ng Y. T., Cheng J. X., Han H. L., Wu Q. J., Wang S. L., Xu B. Y., and Qi S.. 2018. Control of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae) by soil solarization. Crop Prot. 114: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C. H., Hu J. R., and Zhang Y. J.. . 2020. The effects of temperature and humidity on a field population of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 113: 1927–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu, Mitsuaki, 2004. Effects of temperature on growth of Beauveria bassiana F-263, a strain highly virulent to the Japanese pine sawyer, Monochamus alternatus, especially tolerance to high temperatures. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 39: 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J., Cao W., and Feng S., . 2016. Effectiveness of high virulence Bt resources as a means of controlling Bradysia odoriphaga larvae. Chinese J. Appl. Entomol. 53: 1217–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Sowjanya Sree, K., Padmaja V., and Murthy Y. L.. . 2008. Insecticidal activity of destruxin, a mycotoxin from Metarhizium anisopliae (Hypocreales), against Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larval stages. Pest Manag. Sci. 64: 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyelu, O., Oyerinde R., Odu B., and Okonji R.. 2020. Effect of fungal infection on defence proteins of Musca domestica L. and variation of virulence with temperature. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 24: 473–476. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., and Wang S.. . 2017. Insect pathogenic fungi: genomics, molecular interactions, and genetic improvements. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 62: 73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G., Lai Y., Wang G., Chen H., Li F., and Wang S.. . 2017. Insect pathogenic fungus interacts with the gut microbiota to accelerate mosquito mortality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114: 5994–5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H., Gong Q., Fan K., Sun R., Xu Y., and Zhang K., . 2017. Synergistic effect of entomopathogenic nematodes and thiamethoxam in controlling Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang (Diptera: Sciaridae). Biol. Control. 111: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, M., Pang Y., Wang C., and Li Q., . 2005. Biological effect of liliaceous host plants on Bradysia odoriphaga Yang et Zhang (Diptera: Sciaridae). Acta Entomol. Sin. 48: 914. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. K., and Zhang X.. 1985. Notes on the fragrant onion gnats with descriptions of two new species of Bradysia (Sciaridae: Diptera). J. China Agric. Univ. 11: 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, W. L. and Lacey L. A., . 2005. Mortality of different life stages of Rhagoletis indifferens (Diptera: Tephritidae) exposed to the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. J. Entomol. Sci. 40: 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, H., Pell J. K., Alderson P. G., Clark S. J., and Pye B. J.. . 2003. Laboratory evaluation of temperature effects on the germination and growth of entomopathogenic fungi and on their pathogenicity to two aphid species. Pest Manag. Sci. 59: 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F., Xiao M., Berestetskiy A., and Hu Q.. 2021. The Metarhizium anisopliae toxin, destruxin A, interacts with the SEC23A and TEME214 proteins of Bombyx mori. J. Fungi. 7: 460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P., He M., Zhao Y., Ren Y., Wei Y., Mu W., and Liu F.. . 2016. Dissipation dynamics of clothianidin and its control efficacy against Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang in Chinese chive ecosystems. Pest Manag. Sci. 72: 1396–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Zhang H., and Song Y.. . 2018. Identification and characterization of diacylglycerol acyltransferase from oleaginous fungus Mucor circinelloides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66: 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X., Ma T., Zhuang Q., Zhang A., Zhang S., and Yu Y., . 2014. Indoor bioassay of Beauveria bassiana against Bradysia odoriphaga and evaluation on control effect in field. Shandong Agric. Sci. 46: 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G., Xue M., Luo Y., Ji G., Liu F., Zhao H., and Sun X.. . 2017. Effects of short-term heat shock and physiological responses to heat stress in two Bradysia adults, Bradysia odoriphaga and Bradysia difformis. Sci. Rep. 7: 13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]