Abstract

Background.

Performance characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests among children are limited despite the need for point-of-care testing in school and childcare settings. We describe children seeking SARS-CoV-2 testing at a community site and compare antigen test performance to real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and viral culture.

Methods.

Two anterior nasal specimens were self-collected for BinaxNOW antigen and RT-PCR testing, along with demographics, symptoms, and exposure information from individuals ≥5 years at a community testing site. Viral culture was attempted on residual antigen or RT-PCR-positive specimens. Demographic and clinical characteristics, and the performance of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests, were compared among children (<18 years) and adults.

Results.

About 1 in 10 included specimens were from children (225/2110); 16.4% (37/225) were RT-PCR-positive. Cycle threshold values were similar among RT-PCR-positive specimens from children and adults (22.5 vs 21.3, P = .46) and among specimens from symptomatic and asymptomatic children (22.5 vs 23.2, P = .39). Sensitivity of antigen test compared to RT-PCR was 73.0% (27/37) among specimens from children and 80.8% (240/297) among specimens from adults; among specimens from children, specificity was 100% (188/188), positive and negative predictive values were 100% (27/27) and 94.9% (188/198), respectively. Virus was isolated from 51.4% (19/37) of RT-PCR-positive pediatric specimens; all 19 had positive antigen test results.

Conclusions.

With lower sensitivity relative to RT-PCR, antigen tests may not diagnose all positive COVID-19 cases; however, antigen testing identified children with live SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Keywords: COVID-19, epidemiology, infectious diseases, pediatrics, public health

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases in children in the United States reached over 2 million in December 2020 [1]. While children are more likely to be asymptomatic or have milder illness [2–4], children can transmit the virus to other children and adults [5–8].

SARS-CoV-2 testing to identify and isolate infected individuals and quarantine their close contacts is an important part of COVID-19 prevention efforts [9]. Although diagnostic testing is recommended regardless of age, children with symptoms and/or exposures are less likely to undergo diagnostic testing than adults [3, 10–13]. Therefore, screening of asymptomatic individuals, including children, has been suggested as a prevention strategy [3, 10–13].

Community surge testing and screening programs pair well with antigen-based tests due to their low cost and provision of rapid results without specialized equipment [14–18]. Antigen-based tests detect the presence of a specific viral antigen and may be performed on nasopharyngeal or nasal swab specimens from persons of any age [19]. Antigen tests are most sensitive for detecting specimens with high viral loads and correlate well with viral culture [19, 20]. When testing symptomatic adults, antigen-based tests have high concordance with real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which is the gold standard test for SARS-CoV-2 detection [14, 19]. Lower sensitivity and specificity have been observed in asymptomatic adults and in adults who undergo testing more than 7 days from symptom onset [21, 22].

However, there are limited data on antigen test performance in children, who are more likely to be asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Given rapid and wide distribution of antigen tests for both diagnostic and screening testing in children, there is greater need to understand their performance. In this investigation, we describe children who sought SARS-CoV-2 testing at a community testing site and compare BinaxNOW (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) SARS-CoV-2 antigen test performance in children relative to RT-PCR and viral isolation in culture.

METHODS

Investigation Participants and Enrollment

Beginning on November 4, 2020, a COVID-19 surge community testing site opened in Oshkosh, Wisconsin offering SARS-CoV-2 BinaxNOW antigen or RT-PCR testing to the public. Individuals could be tested regardless of symptoms or exposures. In collaboration with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, the University of Wisconsin System, and the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted an investigation at the surge testing site between November 16, 2020 and December 15, 2020 to evaluate and validate the performance of the site-selected BinaxNOW antigen test in a community setting [22]. Individuals ≥5 years of age who sought testing at this site and received an antigen test were eligible to participate in the CDC investigation, and a convenience sample was recruited. For those who chose to participate, patient information was collected, along with self-collected paired nasal swabs for both antigen and RT-PCR testing. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy (See, for example, 45 C.F.R. part 46.102(l)(2), 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.).

Data Collection and Testing Algorithm

Participants completed a self-administered standardized paper questionnaire, which captured demographics, symptoms, and known exposure to COVID-19 case(s) in the 14 days prior to specimen collection. Parents or guardians completed questionnaires for children who were unable to do so on their own. Approximately 30 minutes after community testing site staff completed a participant’s antigen test, the participant provided 2 additional observed self-collected anterior nasal swabs, sometimes with assistance from a household member (e.g., for young children or persons with disabilities). Participants were instructed to simultaneously insert 1 swab into each nostril, rotate 5 times, then switch nostrils and repeat the process. CDC staff performed the antigen test with 1 of the 2 additional nasal swabs per manufacturer instructions [20]. The second simultaneously collected nasal swab was placed in transport media (UTM, Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA) for RT-PCR testing. COVID-19 TaqPath RT-PCR testing was completed at the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute [23]. Specimens with a cycle threshold (Ct) value (indicating levels of viral RNA) of ≤37 for at least 2 of 3 SARS-CoV-2 gene targets (ORF1ab, S-gene, and N-gene) on the RT-PCR assay were considered positive [23]. Virus isolation was attempted at CDC using Vero CCL-81 cell suspension in 96-well format from residual RT-PCR specimens from all patients who tested positive by either RT-PCR or antigen testing [24].

An antigen test was indeterminant when a control line did not appear or remained blue [20]. Inconclusive RT-PCR results were only positive for 1 of the 3 targets [23]. Participants with indeterminate antigen results or inconclusive RT-PCR results were excluded from analyses.

Some individuals registered for antigen tests on more than 1 day throughout the investigation period and could therefore contribute multiple specimens to the investigation if tested on different days.

Analysis

We defined children as participants <18 years old and adults as ≥18 years old. We categorized children in the following age groups: 5–8 years old, 9–12 years old, 13–15 years old, and 16–17 years old. Participants who reported ≥1 of COVID-19 symptoms, listed in the Council for State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) clinical criteria [25], at the time of specimen collection were considered symptomatic; participants who did not report any COVID-19 symptoms at the time of specimen collection were considered asymptomatic. Participants met the CSTE clinical criteria for COVID-19 (a surveillance case definition used by public health surveillance systems within the United States) if they had a cough, shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, a new loss of taste or smell, or had 2 or more of the following: fever, chills, rigors, muscle aches, headache, sore throat, nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, and congestion [25]. An exposure was defined as reporting being within 6 feet of a person with a diagnosis of COVID-19 for at least 15 minutes in the past 14 days. We compared demographics, exposures, and symptoms in children to adult participants. We used chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests when cell values were <5, to assess differences among dichotomous/categorical characteristics and considered P values <.05 as statistically significant. Median days with interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated for the time interval between date of symptom onset and/or last known exposure and the specimen collection date.

Results from the antigen test specimen collected at the same time as the RT-PCR specimens were used for all analyses; we have previously shown that sensitivity of repeat antigen testing was similar, and specificity remained high [22]. With analysis stratified by children and adults, we assessed concordance between antigen and RT-PCR tests using Cohen’s Kappa statistic. Antigen test sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated with RT-PCR results as the reference; 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each performance characteristic were determined with the exact binomial method. We calculated percentage positive by antigen test and RT-PCR for all age categories. To further evaluate test differences, we compared N-gene Ct values, detected in all positive RT-PCR specimens, and viral culture results. Test results were compared based on age group, symptom, and exposure status. Two-sided Mann-Whitney tests were used for the comparison of Ct values. Statistical analysis was performed in SAS 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., and figures were prepared with R version 4.0.2.

RESULTS

Study Population

Between November 16 and December 15, 2020, data on 2127/9473 specimens tested at the community surge testing site were collected; 13 specimen pairs with inconclusive or missing RT-PCR results and 4 with indeterminate antigen test results were excluded from further analysis. Males provided 42.9% (905/2110) and non-Hispanic Whites provided 88.9% (1876/2110) of specimens (Table 1). Among all specimens, 89.3% (1885/2110) were collected from 1807 adults and 10.7% (225/2110) were collected from 217 children.

Table 1.

Demographic Information, Exposure, and Symptoms of Participants Testing at a Community Testing Site by Age Group, Wisconsin, November-December 2020

| No (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children (<18 yr), N = 225 | Adults (≥18 yr), N = 1885 | All Participants, N = 2110 | P Value | |

|

| ||||

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 5–8 | 42 (18.7) | – | 42 (2.0) | NA |

| 9–12 | 62 (27.6) | – | 62 (2.9) | |

| 13–15 | 66 (29.3) | – | 66 (3.1) | |

| 16–17 | 55 (24.4) | – | 55 (2.6) | |

| 18 to ≥65 | – | 1885 (100) | 1885 (89.3) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 111 (49.3) | 794 (42.1) | 905 (42.9) | .10a |

| Female | 113 (50.2) | 1070 (56.8) | 1183 (56.1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | 21 (1.1) | 22 (1.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 187 (83.1) | 1689 (89.6) | 1867 (88.9) | <.01a |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 (7.1) | 50 (2.7) | 66 (3.1) | |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 5 (2.2) | 30 (1.6) | 35 (1.7) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 4 (1.8) | 17 (0.9) | 21 (1.0) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic | 3 (1.3) | 10 (0.5) | 13 (0.6) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 0 (0) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | |

| Unknown | 10 (4.4) | 86 (4.6) | 96 (4.5) | |

| Contact with a COVID-19 case in the past 14 days | ||||

| Yes | 112 (49.8) | 782 (41.5) | 894 (42.4) | .05 |

| Median (IQR) days since exposure | 4 (1–6) | 4 (1–6) | 4 (1–6) | |

| No | 80 (35.6) | 750 (39.8) | 830 (39.3) | |

| Don’t know/unknown | 33 (14.7) | 353 (18.7) | 386 (18.3) | |

| ≥1 symptom at time of testing | ||||

| Yes | 122 (54.2) | 1066 (56.6) | 1188 (56.3) | .74a |

| No | 99 (44.0) | 778 (41.3) | 877 (41.6) | |

| Unknown symptom status | 4 (1.8) | 41 (2.2) | 45 (2.1) | |

| CSTE clinical criteriab at time of testing | ||||

| Yes | 83 (36.9) | 844 (44.8) | 927 (43.9) | .06a |

| No | 138 (61.3) | 1000 (53.1) | 1138 (53.9) | |

| Unknown symptom status | 4 (1.8) | 41 (2.2) | 45 (2.1) | |

| Reported symptoms at time of testingc | ||||

| Congestion | 76 (62.3) | 592 (55.5) | 668 (56.2) | .15 |

| Sore throat | 43 (35.2) | 369 (34.6) | 412 (34.7) | .89 |

| Headache | 40 (32.8) | 466 (43.7) | 506 (42.6) | .02 |

| Cough | 29 (23.8) | 359 (33.7) | 388 (32.7) | .03 |

| Fatigue | 20 (16.4) | 368 (34.5) | 388 (32.7) | <.01 |

| Muscle aches | 15 (12.3) | 265 (24.9) | 280 (23.6) | <.01 |

| Chills | 14 (11.5) | 140 (13.1) | 154 (13.0) | .61 |

| Loss of smell | 12 (9.8) | 94 (8.8) | 106 (8.9) | .71 |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (9.8) | 44 (4.1) | 56 (4.7) | <.01 |

| Nausea | 11 (9.0) | 84 (7.9) | 95 (8.0) | .66 |

| Fever | 10 (8.2) | 85 (8.0) | 95 (8.0) | .93 |

| Shortness of breath | 9 (7.4) | 118 (11.1) | 127 (10.7) | .21 |

| Loss of taste | 6 (4.9) | 86 (8.1) | 6 (4.9) | .22 |

| Diarrhea | 5 (4.1) | 102 (9.6) | 107 (9.0) | .05 |

| Rigors | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | .10a |

| Days since symptom onsetc | ||||

| 0–2 days since onset | 68 (55.7) | 458 (43.0) | 526 (44.3) | .03a |

| 3–5 days since onset | 33 (27.0) | 303 (28.4) | 336 (28.3) | |

| 6–7 days since onset | 4 (3.3) | 63 (5.9) | 67 (5.6) | |

| >7 days since onset | 5 (4.1) | 111 (10.4) | 116 (9.8) | |

| Unknown symptom onset | 12 (9.8) | 131 (12.3) | 143 (12.0) | |

Abbreviations: CSTE, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Fisher exact P value.

CSTE clinical criteria is a surveillance case definition used within public health surveillance systems within the United States due to the nonspecific nature of symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Percentage denominator is participants reporting ≥1 symptom.

P value compares <18 years and ≥18 years.

Among specimens from children, 49.3% (111/225) were from males and 83.1% (187/225) were from non-Hispanic Whites. In this population, 18.7% (42/225) were from participants aged 5–8 years, 27.6% (62/225) were from participants aged 9–12 years, 29.3% (66/225) were from participants aged 13–15 years, and 24.4% (55/225) were from participants aged 16–17 years.

Comparing specimens from adults and children, 41.5% (782/1885) were from adults who reported exposure to a COVID-19 case in the past 14 days vs 49.8% (112/225) of specimens from children (P = .05). Exposures among children aged 16–17 years were significantly higher than adults (60%, 33/55, P = .02, Supplementary Table 1). Most specimens were from symptomatic participants for both children (54.2%; 122/225) and adults (56.6%; 1066/1885) (P = .74). Compared to adults, a higher proportion of specimens were from symptomatic children who reported only one symptom (35.2% vs 24.1%, P < .01). Eighty-three (36.9%) child and 844 (44.8%) adult specimens were from individuals reporting symptoms that matched the CSTE clinical criteria for COVID-19 (P = .06). Specimens were collected a median of 2-days post-symptom onset from children (IQR 1–3; 9.8% missing onset date) and 3-days post-symptom onset from adults (IQR 1–5; 12.3% missing onset date).

RT-PCR-Positive Participants

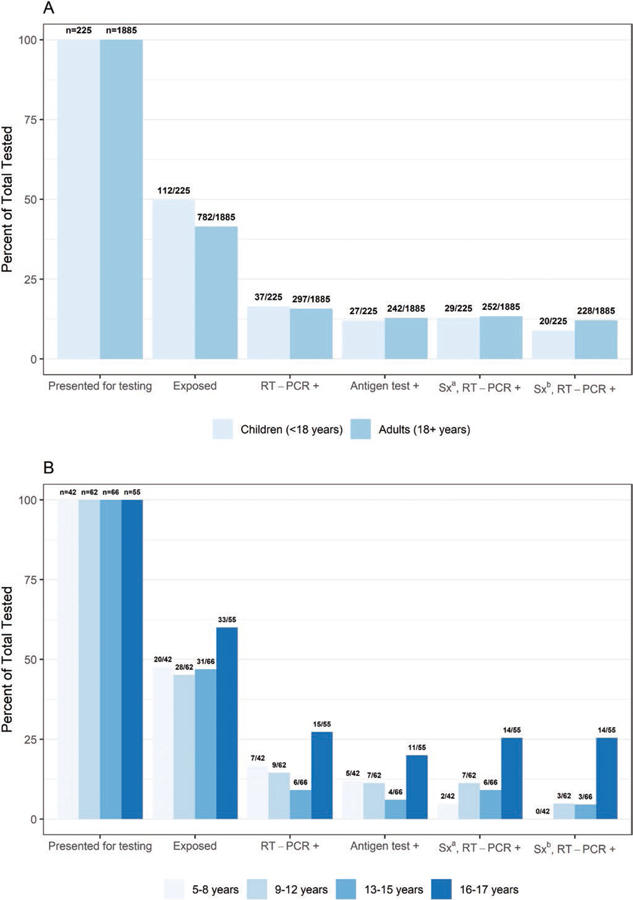

RT-PCR positivity was 15.8% (297/1885) among specimens from adults and 16.4% (37/225) among specimens from children (Figure 1). Among specimens from children by age group, RT-PCR positivity was 16.7% (7/42) for children 5–8 years, 14.5% (9/62) for children 9–12 years, 9.1% (6/66) for children 13–15 years, and 27.3% (15/55) for children 16–17 years (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Specimens from participants aged 16–17 years had significantly higher positivity by RT-PCR than participants aged <16 years (P = .01) and adults (P = .02).

Figure 1.

(A) Percentage presenting for testing, exposed, real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or antigen test-positive and (B) positive and symptomatic by age group, collected at a community testing site – Oshkosh, Wisconsin, November-December 2020. aSx: Symptomatic defined as reporting ≥1 symptom at specimen collection. bSx: Symptomatic defined as reporting symptoms meeting the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) clinical criteria for COVID-19.

The proportion of RT-PCR-positive specimens from exposed children (56.8%) and symptomatic children (78.4%) was similar to the proportion of RT-PCR-positive specimens from exposed (54.9%, P = .98) and symptomatic (84.8%, P = .33) adults (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Among RT-PCR-positive specimens, a lower proportion was from children who reported symptoms meeting the CSTE clinical criteria than from adults who reported meeting the CSTE clinical criteria (54.1% vs 76.8%, P = .01).

Median Ct values did not differ between specimens from children and adults (P = .46, Table 2) or among pediatric age groups (5–8 years: 22.2, 9–12 years: 22.8, 13–15 years: 23.4, and 16–17 years 20.6, P = .90; Supplementary Table 4). The median Ct value of RT-PCR-positive specimens from children did not differ by symptom status or by symptom duration; among RT-PCR-positive specimens from adults, the median Ct value also did not differ by symptom status but was lower among specimens from adults tested within 7 days of symptom onset compared to adults tested >7 days since symptom onset (Ct value 20.9 vs 27.7, P < .01).

Table 2.

SARS-CoV-2 N-Gene RT-PCR Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values and Virus Isolation, Children, and Adults

| Children |

Adults |

|||||||

| RT-PCR Median Ct (IQR) |

Virus Isolated |

RT-PCR Median Ct (IQR) |

Virus Isolated |

|||||

| Overall | 22.5 (18.8–27.3) | 51.4% (19/37) | 21.3 (17.8–26.7) | 60.5% (181/299) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| P Value | P Value | P Value | P Value | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Contact with a COVID-19 case in the past 14 days | ||||||||

| Yes | 21.4 (18.6–23.8) | .21 | 52.4% (11/21) | .89 | 21.2 (17.6–27.8) | .60 | 63.0% (104/165) | .33 |

| No or unknown | 24.4 (19.7–30.3) | 50.0% (8/16) | 21.5 (17.9–26.6) | 57.5% (77/134) | ||||

| Current symptomsa | ||||||||

| No symptoms | 23.2 (21.6–31.6) | .39 | 57.1% (4/7) | 1.00b | 21.8 (18.7–30.3) | .25 | 47.6% (20/42) | .07 |

| ≥1 symptom | 22.5 (18.6–26.9) | 48.3% (14/29) | 21.4 (17.8–26.6) | 62.5% (158/253) | ||||

| No CSTE clinical criteriac | 22.5 (18.6–29.6) | .65 | 56.3% (9/16) | .50 | 21.2 (18.3–28.0) | .39 | 54.5% (36/66) | .28 |

| CSTE clinical criteria | 22.6 (18.7–26.8) | 45.0% (9/20) | 21.4 (17.7–26.6) | 62.0% (142/229) | ||||

| ≤7 days since onset | 21.4 (17.8–26.9) | .15 | 53.8% (14/26) | .48b | 20.9 (17.5–25.6) | <.001 | 67.4% (147/218) | .001 |

| >7 days since onset | 28.8 (23.8–33.8) | 0% (0/2) | 27.7 (20.9–30.9) | 34.5% (10/29) | ||||

| Antigen test result | ||||||||

| Positive | 20.2 (17.6–23.0) | <.001 | 70.4% (19/27) | <.001b | 19.8 (17.3–23.6) | <.001 | 71.1% (172/242) | <.001 |

| Negative | 31.1 (29.8–32.5) | 0% (0/10) | 30.6 (28.8–33.3) | 15.8% (9/57) | ||||

Abbreviations: CSTE, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; Ct, cycle threshold; IQR, interquartile range; RT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Excluding specimens where symptoms were not reported (n = 1 for children and n = 4 for adults). For days since symptom onset, also excluding specimens with unknown symptom onset date (n = 1 for children and n = 6 for adults).

Fisher’s exact P value.

CSTE clinical criteria is a more conservative case definition used within public health surveillance systems within the United States due to the nonspecific nature of symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Virus was isolated from 51.4% (19/37) of RT-PCR-positive specimens from children and 60.5% (181/299) of RT-PCR- or antigen-positive specimens from adults (Table 2). The proportion of positive specimens with isolated virus did not differ among children by exposure (52.4% exposed, P = .89) or symptom (48.7% symptomatic, P = 1.00). The proportion of positive specimens with isolated virus differed among adults by symptom duration prior to collection (≤7 days, 67.4% vs >7 days, 34.5%; P = 0.001).

Antigen Test Performance Compared to RT-PCR Test and Viral Isolation

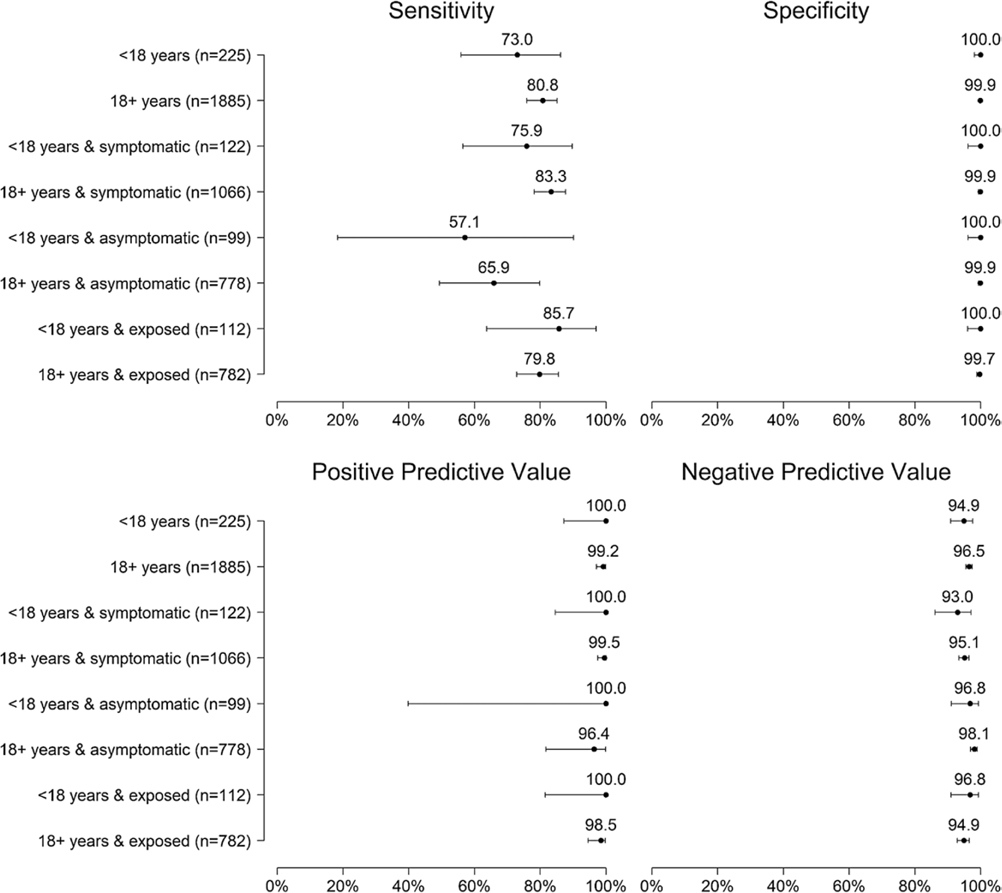

Antigen test positivity was 12.8% (242/1885) among adults and 12.0% (27/225) among children (Figure 1; positivity by pediatric age group in Supplementary Table 3). High concordance between antigen test and RT-PCR test was observed, but lower when testing specimens from children (k 0.82, 95% CI 0.71–0.93) than adults (k 0.87, 95% CI 0.84–0.93). Antigen test sensitivity was 73.0% (27/37, 95% CI 55.9%-86.2%) among specimens from children and 80.8% (240/297, 95% CI 75.9%-85.1%) among specimens from adults; specificity was 100% (188/188, 95% CI 98.1%-100%) and 99.9% (1586/1588, 95% CI 99.5%-100%), respectively; PPV was 100% (27/27, 95% CI 87.2%-100%) and 99.2% (240/242, 95% CI 97.0%-99.9%), respectively; NPV was 94.9% (188/198, 95% CI 90.9%-97.6%) and 96.5% (1586/1643, 95% CI 95.5%-97.4%), respectively (Figure 2 and Supplementary Tables 5, 6 and 7).

Figure 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of antigen test compared with real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test among pediatric and adult participants overall and by symptom and exposure status, Oshkosh, Wisconsin, November-December 2020.

Test sensitivity was 75.9% (95% CI 56.5%-89.7%) among specimens from symptomatic children compared with 57.1% (95% CI 18.4%-90.1%) among asymptomatic children, and 85.7% (6/7) of antigen-negative, RT-PCR-positive specimens were from symptomatic children tested ≤7 days from symptom onset. Among specimens from children with reported exposure, test sensitivity was 85.7% overall (18/21, 95% CI 63.7%-97.0%), 88.2% with symptoms (15/17, 95% CI 63.6%-98.5%), and 66.7% without symptoms (2/3, 95% CI 9.4%-99.2%) (Supplementary Figure 2). Specificity and PPV were 100% among specimens from symptomatic, asymptomatic, and exposed children. Antigen-positive or RT-PCR-positive specimens from children were collected a median of 4 days (IQR 0–6) since last known exposure, while antigen-negative, RT-PCR-positive specimens were collected a median of 2 days (IQR 1–6) from known exposure.

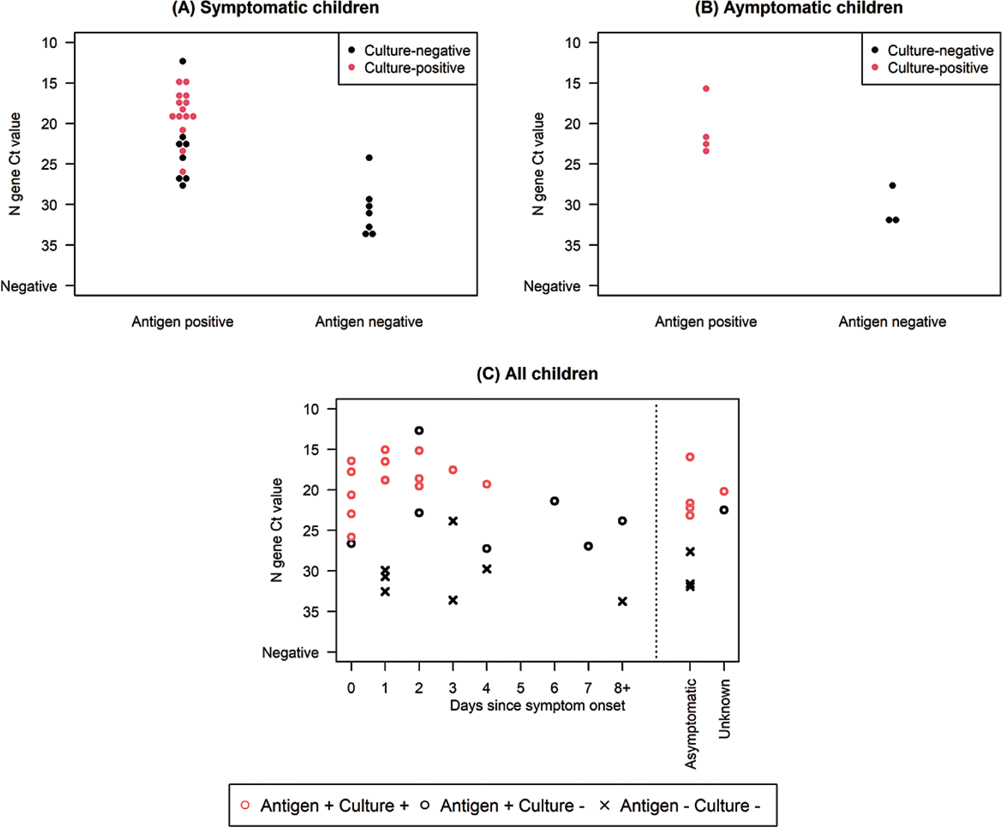

Among specimens from both children and adults with a positive RT-PCR result, Ct values for specimens with positive antigen tests were lower than for specimens with negative antigen tests (Table 2, Figure 3, and Supplementary Figure 3). Among RT-PCR and antigen-positive specimens from children, virus was isolated from 70.4% (19/27); 73.7% (14/19) were from symptomatic children, 21.1% (4/19) were from asymptomatic children, and 5.3% (1/19) were from children with unknown symptom status. No (0/10) virus was isolated from RT-PCR-positive, antigen-negative specimens from children.

Figure 3.

N-gene cycle threshold value distribution and viral isolation among real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or antigen-positive (A) symptomatic children (B) asymptomatic children, (C) all children by days since symptom onset, Oshkosh, Wisconsin, November-December 2020. A and B are excluding 1 child with unknown symptom status.

Discussion

We describe children who sought testing at a community site and provide an opportunity to better understand antigen test performance in children. As of January 2021, 11% of lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States were <18 years of age [26], and in this investigation, approximately 11% of specimens and 11% of RT-PCR-positive specimens were from children. Over half of pediatric specimens tested were from symptomatic children (a similar proportion to adults), but children generally had fewer symptoms. In particular, RT-PCR-positive specimens from younger children (5–8 years) were from either asymptomatic children or children only reporting nasal congestion. Although children are often asymptomatic or have mild, nonspecific symptoms [2–4], they still can transmit SARS-CoV-2 [4–8]. Here, virus was isolated in 51% of RT-PCR-positive specimens from children, and Ct values were similar to adults. While antigen testing sensitivity in specimens from children was 73%, compared to 81% in specimens from adults, antigen-positive results were received for all RT-PCR-positive specimens from children with isolated virus.

Antigen test sensitivity among children and adults was consistent with similar studies conducted at community or pediatric clinic testing sites [27, 28]. Among specimens from children, antigen test sensitivity was highest (86%) for those with a known exposure, whereby the probability of infection is higher [9, 13]. More older teenagers (16–17 years) reported a known exposure and had a higher percentage positivity than adults. However, whereas few young children (5–8 years) were symptomatic almost all RT-PCR-positive teenagers 16–17 years were symptomatic, and the percentage of specimens from individuals meeting the CSTE clinical criteria appeared to increase by age. Antigen testing may be useful in this high-prevalence and exposed population, particularly if used as part of a serial testing strategy [29]. Testing pediatric populations, particularly teenagers, with any symptoms or possible exposures is important due to their high levels of exposure and risk of community transmission. Confirmatory nucleic acid amplification testing is recommended for a negative antigen result in individuals with symptoms or known exposures [19].

Median Ct values, which indicate levels of viral RNA, were similar by age, in line with other studies [30, 31]. Median Ct values were also similar among specimens from symptomatic and asymptomatic children, which contrasts with previous studies that found lower Ct values in symptomatic compared with asymptomatic individuals, including those who have recovered from infection [14, 18, 32, 33]. While lower Ct values may suggest higher levels of virus, Ct values are not necessarily a measurement of viral loads [14, 18, 32]. Considering the short duration between testing and contact with a COVID-19 case (ie, 2–4 days) in this investigation, asymptomatic participants may predominantly be pre-symptomatic instead of at the recovery stage. This may explain why we did not observe differences in Ct values by symptom status.

As reported in other studies [18, 20, 27], Ct values were significantly higher among specimens with antigen-negative results than those with antigen-positive results. In children, antigen testing also performed better with RT-PCR-positive specimens that were culture-positive, than with those that were culture-negative. Viral culture may be insensitive and viral isolation may not perfectly correlate with infectiousness [14, 18, 32]; but it is noteworthy that we detected no live virus in specimens from children with negative antigen results.

Antigen tests were highly specific regardless of symptom status or exposures. There were no antigen-positive, RT-PCR-negative results in specimens from children, resulting in a PPV of 100% in this moderate-high prevalence setting. Our finding is similar to what was reported at a community testing site in San Francisco and at an outpatient clinic in West Bend, where no antigen-positive RT-PCR-negative results were received among participants <18 years [16, 28]. The high specificity and ability of these tests to identify those without disease promote efficient use of scarce public health resources for disease investigation and contact tracing; the specificity also prevents individuals with low-pretest probability from having to isolate unnecessarily due to false-positive results. As widespread antigen testing in K-12 schools is considered [9], the advantages and limitations of antigen tests should be taken into account when designing testing strategies and interpreting results. Background levels of community incidence, access to other viral testing options (ie, RT-PCR testing), and single vs serial testing approaches should all be considered alongside SARS-CoV-2 antigen test performance in children.

Our investigation was subject to several limitations. Investigation participants were a convenience sample of largely non-Hispanic White participants and the findings might not be generalizable to other settings. The sample size may have affected the ability to detect significant differences. Furthermore, demographics, exposures, and symptoms were self-reported, so they may not have been known, provided, accurate, or may be symptoms of other respiratory viral infections. Similarly, not many children had a symptom onset >7 days prior to testing, and we were unable to draw conclusions on test performance in this group. Finally, we limited our antigen testing to the BinaxNOW antigen platform, so it is unclear how these results may be generalizable to other antigen platforms.

In conclusion, while children reported fewer symptoms than adults, RT-PCR Ct values and virus isolation results were similar to adults, further supporting that children play a role in transmission [5, 30, 34–36]. Antigen testing was highly specific; estimates suggest that test sensitivity may be highest among exposed children and could be useful in this population regardless of where testing may occur. From this study and others, antigen tests had lower, although not necessarily statistically significant, sensitivity among children compared with adults; this lower sensitivity should be considered when developing diagnostic testing programs. However, all culture-positive specimens from children had a positive antigen test, indicating that antigen testing identified children with live SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to thank the contributions of Allen Bateman, Alana Sterkel, and Mary Wedig from the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene and the members of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response Team: John Paul Bigouette, Juliana DaSilva, Alicia Fry, Aron Hall, Emiko Kamitane, Sandor Karpathy, Marie Killerby, Nancy Knight, Shirley Lecher, Kaitlin Mitchell, Tarah Somers, and Miriam Van Dyke.

Financial support.

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Names of specific vendors, manufacturers, or products are included for public health and informational purposes; inclusion does not imply endorsement of the vendors, manufacturers, or products by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society online.

References

- 1.Jenco M. COVID-19 Cases in Children Surpass 2 Million. Itasca, IL: AAP News: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2020. https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/12/29/covid-2million-children-122920 [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children – United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69(14): 422–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim L, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of children aged <18 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 – COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-July 25, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1081–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han MS, Choi EH, Chang SH, et al. Clinical characteristics and viral RNA detection in children with Coronavirus disease 2019 in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Pediatr 2021; 175(1):73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laws RL, Chancey RJ, Rabold EM, et al. Symptoms and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among children — Utah and Wisconsin, March–May 2020. Pedriatrics 2021; 147(1):e2020027268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez AS, Hill M, Antezano J, et al. Transmission dynamics of COVID-19 outbreaks associated with child care facilities – Salt Lake City, Utah, April-July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1319–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz NG, Moorman AC, Makaretz A, et al. Adolescent with COVID-19 as the source of an outbreak at a 3-week family gathering – four states, June-July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1457–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szablewski CM, Chang KT, Brown MM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission and infection among attendees of an overnight camp – Georgia, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1023–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening K-12 Students for Symptoms of COVID-19: Limitations and Considerations. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/symptom-screening.html

- 10.Leeb RT, Price S, Sliwa S, et al. COVID-19 trends among school-aged children – United States, March 1-September 19, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1410–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leidman E, Duca LM, Omura JD, Proia K, Stephens JW, Sauber-Schatz EK. COVID-19 trends among persons aged 0–24 years – United States, March 1-December 12, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70(3):88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poline J, Gaschignard J, Leblanc C, et al. Systematic SARS-CoV-2 screening at hospital admission in children: a French prospective multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 72(12):2215–2217. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Information for Pediatric Healthcare Providers. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/pediatric-hcp.html

- 14.Pray IW, Ford L, Cole D, et al. Performance of an antigen-based test for asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing at two university campuses – Wisconsin, September-October 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 69(5152):1642–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert E, Torres I, Bueno F, et al. Field evaluation of a rapid antigen test (Panbio™ COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device) for COVID-19 diagnosis in primary healthcare centres. Clin Microbiol Infec 2020; 27(3):472.e7–472.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilarowski G, Lebel P, Sunshine S, et al. Performance characteristics of a rapid severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 antigen detection assay at a public plaza testing site in San Francisco. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:1139–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin R. The challenges of expanding rapid tests to curb COVID-19. JAMA 2020; 324:1813–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prince-Guerra JL, Almendares O, Nolen LD, et al. Evaluation of Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 infection at two community-based testing sites – Pima County, Arizona, November 3–17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70(3):100–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Interim Guidance for Antigen Testing for SARS-CoV-2. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antigen-tests-guidelines.html

- 20.Pekosz A, Cooper CK, Parvu V, et al. Antigen-based testing but not real-time polymerase chain reaction correlates with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 viral culture. Clin Infect Dis 2021:ciaa1706. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card (PN 195–000) – Instructions for Use. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/141570/download

- 22.Shah MM, Salvatore PP, Ford L, et al. Performance of repeat BinaxNOW™ SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing in a community setting, Wisconsin, November-December 2020. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73(Suppl 1):S54–S57. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ThermoFisher Scientific. TaqPath™ COVID-19 Combo Kit and TaqPath™ COVID-19 Combo Kit Advanced* Instructions for Use. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/136112/download

- 24.Harcourt J, Tamin A, Lu X, et al. Isolation and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 from the first US COVID-19 patient. bioRxiv 2020.03.972935 [Preprint]. March 7, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2021. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.02.972935v2

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020 Interim Case Definition, Approved August 5, 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021.https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/coronavirus-disease-2019-2020-08-05/

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

- 27.Pollock NR, Savage TJ, Wardell H, et al. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antigen and RNA concentrations in nasopharyngeal samples from children and adults using an ultrasensitive and quantitative antigen assay. J Clin Microbiol 2021; 59(4):e03077–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck ET, Paar W, Fojut L, Serwe J, Jahnke RR. Comparison of the Quidel Sofia SARS FIA test to the Hologic Aptima SARS-CoV-2 TMA test for diagnosis of COVID-19 in symptomatic outpatients. J Clin Microbiol 2021;59(2):e02727–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paltiel AD, Zheng A, Walensky RP. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 screening strategies to permit the safe reopening of college campuses in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e2016818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heald-Sargent T, Muller WJ, Zheng X, Rippe J, Patel AB, Kociolek LK. Age-related differences in nasopharyngeal Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) levels in patients with mild to moderate Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Pediatr 2020; 174(9):902–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchan BW, Hoff JS, Gmehlin CG, et al. Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 PCR cycle threshold values provide practical insight into overall and target-specific sensitivity among symptomatic patients. Am J Clin Pathol 2020; 154:479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang CG, Lee KM, Hsiao MJ, et al. Culture-based virus isolation to evaluate potential infectivity of clinical specimens tested for COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58(8):e01068–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salvatore PP, Dawson P, Wadhwa A, et al. Epidemiological correlates of PCR cycle threshold values in the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72(11):e761–e767. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaafar R, Aherfi S, Wurtz N, et al. Correlation between 3790 quantitative polymerase chain reaction–positives samples and positive cell cultures, including 1941 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 isolates. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72(11):e921. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, et al. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2021; 2:e13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, et al. Predicting infectious severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:2663–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.