Abstract

Most Americans think that the country is politically divided and polarization will only get worse, not better. Such perceptions of polarization are widespread, but we do not know enough about their effects, especially those unrelated to political variables. This study examines the consequences of perceived polarization for levels of social trust in the United States. Trust in fellow citizens is the backbone of a well-functioning democracy, given its role in promoting social cohesion and facilitating collective action. Using nationally representative panel data, as well as an original survey experiment, I find that perceived polarization directly undermines Americans’ trust in each other. A belief that members of society share common values fosters social trust, but perceptions of partisan divisions and polarization make people less trusting of their fellow citizens. Due to perceived polarization, people are less likely to believe that others can be trusted to do the right thing, which in turn decreases their willingness to cooperate for good causes. I discuss the implications of these findings for society’s ability to work together toward common goals.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11109-022-09787-1.

Keywords: Polarization, Social trust, Perceptions of polarization, Panel data, Experiment

Introduction

It is impossible for even the casual observer of politics not to notice polarization today. We hear America is politically divided and polarization is here to stay, at least for a while longer. Americans clearly seem to accept this notion and perceive the country to be experiencing growing partisan divisions and tribalism, at the expense of common ground and shared values (Ahler, 2014; Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016a).

Perceptions of political polarization are widespread. About nine-in-ten Americans view the country as divided over politics and partisan conflicts (Pew Research Center, 2020; PRRI, 2019). These perceptions are likely to prevail, as roughly two-thirds of the public expect polarization to only worsen in the future (Pew Research Center, 2019a).

A belief that members of society share similar values and norms undergirds social trust (Offe, 1999). Trust in fellow citizens—so-called generalized social trust—acts as the social glue that binds people together in harmony and for the common good (Putnam, 2000). That being so, if an increasing number of people feel that there is more that divides them than unites them, what consequences does that have for citizens’ trust in each other?

This question is important because social trust is the foundation of a well-functioning democracy. It is a vital attribute every society strives to cultivate; social trust promotes civic engagement, facilitates cooperation, fosters social harmony, and supports democratic systems (Fukuyama, 1995; Paxton, 1999; Putnam, 1993, 2000; Uslaner, 2002). This question is especially timely and relevant, given that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of trust among citizens when responding to crises. A society’s trust levels represent how effectively it can perform collective action (Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 1993), which is critical for tackling shared challenges, such as public health, climate change, inequality, and other societal ills that require concerted efforts by society as a whole.

This study focuses on the public perception of polarization and its consequences for levels of generalized social trust. Past studies on perceived polarization have examined its effects mostly with respect to political variables, such as whether it leads to the actual polarization of political attitudes and how it impacts political behavior (Ahler, 2014; Enders & Armaly, 2019; Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016b). Perhaps most relevant to this study, Enders and Armaly (2019) find, based on cross-sectional data, that perceived polarization is associated with lower political trust, or trust in government.

Nevertheless, little is known about the relationship between perceived polarization and social trust, including whether that relationship is causal. Social trust (trust in people in general) and political trust (trust in political leaders and institutions) are different kinds of trust with different antecedents. For instance, trust in government is heavily shaped by evaluations of government performance and whether or not one supports the party-in-power (Citrin, 1974), and it is not the same as how much one trusts other people (Newton, 2001). While social and political trust tend to move in tandem at the macro level (Keele, 2007), the empirical evidence on the individual level is inconclusive; if anything, it weighs more heavily for a weak association between the two (Uslaner, 2002; Delhey & Newton, 2003; Kaase, 1999; see Brehm & Rahn, 1997 for an exception).

This suggests that prior work on polarization and political trust does not reveal what effects polarization might have on social trust. My study is unique in that it focuses on the direct connection between perceived polarization and social trust. While social and political trust are both crucial to the quality of democracy, many view social trust as further-reaching in its effects, given its relation to various outcomes across multiple domains, including economic growth, effective governance, social and political inclusion, citizen engagement, low crime and corruption rates, and healthy and happy citizenry (Carl & Billari, 2014; Knack, 2002; Knack & Keefer, 1997; Neilson & Paxton, 2010; Putnam, 2000; Reeskens, 2013; Rothstein & Uslaner, 2005; Uslaner, 2002).

My study contributes to the literature by demonstrating a direct causal link between perceived polarization and social trust. Using data from a nationally representative panel survey and an original survey experiment, I find that perceptions of polarization, which are held by most Americans today, lead to the erosion of social trust. The results are robust to controlling for actual polarization defined in both affective and ideological terms. Perceived polarization makes individuals more distrustful of their fellow citizens and discourages them from cooperating with others to contribute to the public good. In short, it fundamentally impacts the ways Americans view and interact with each other. I discuss the implications of these findings for how they undermine our ability to trust and work together toward common goals.

Perceived Partisan Polarization and Social Trust

Many Americans think that the country is politically polarized, with fewer and fewer shared values and common interests to build common ground. Only a small share (15%) say that Americans have a lot in common with each other (More in Common, 2018). Public perception of a divided America has increased substantially over the past decades and is expected to last for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, we do not know enough about its effects on our society, particularly its effects besides those related to political variables.

This study examines whether these widespread perceptions of polarization harm Americans’ trust in each other. I focus on perceived polarization, i.e., the extent to which one sees the nation as polarized, rather than actual ideological or affective polarization, which refers to adopting more extreme issue attitudes or polarized feelings toward political groups.

Perceived polarization is not the same as actual polarization. First, most Americans across the political spectrum—Republicans, Democrats, and Independents—exhibit high perceptions of polarization (PRRI, 2019), which makes perceived polarization a more general and widespread phenomenon. People may view the country as politically polarized without having polarized attitudes themselves, although polarized attitudes can amplify perceptions of polarization (Westfall et al., 2015). Second, perceived polarization tends to be extreme and exaggerated. Many see the country as more severely polarized than it actually is—the perceived level of polarization can be twice as large as its actual level (Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016a).

Perceived polarization is as important a phenomenon as actual polarization, if not more. Perception of polarization exceeds actual polarization, and importantly, it can affect citizen attitudes and behavior, independent of actual polarization (Enders & Armaly, 2019). People’s own perceptions of a given phenomenon are powerful in shaping their attitudes, often more so than actual, objective reality (van Setten et al., 2017).

Past research on the effects of perceived polarization has primarily focused on political outcomes. For example, perceived polarization is found to intensify negative feelings toward those of the other party (Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016b). On ideological polarization, the results are mixed; some studies find that it depolarizes issue attitudes (Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016b), while others find it drives attitude extremity (Ahler, 2014). Additionally, perceived polarization is associated with lower political trust and efficacy and higher political participation (Enders & Armaly, 2019).

This study demonstrates that perceived polarization has broader consequences, beyond the political sphere. Specifically, I focus on how it affects trust in other members of society, called generalized social trust. As discussed above, social trust is conceptually different from political trust or institutional trust, which refers to one’s confidence in political institutions, authorities, and systems (Uslaner, 2002).

Generalized social trust also differs from trust in family, friends, and other personal contacts (personalized trust) and from trust in those who share similar characteristics (ingroup trust). Rather, it is a generalized belief about what “most people” are like, including those whom one does not know and those different from oneself (Delhey et al., 2011; Uslaner, 2002). This trust is based on the belief that most people have good intentions and adhere to a set of norms shared within society. Our society teaches us the values of honesty and integrity, so we are provided with common moral codes that prescribe good behaviors. When it comes to anonymous fellow citizens, trusting them means we expect them, even absent personal familiarity, to abide by and act as per shared norms (Fukuyama, 1995; Offe, 1999).

This generalized trust in other people plays a particularly important role as societies become more anonymous and heterogeneous. Many of our daily interactions require us to trust people we know little, and generalized social trust increases people’s comfort levels when dealing with strangers for productive exchange (Offe, 1999). Social trust is what makes “social interactions in complex, diversified societies work” (Stolle, 2002, 399). Trust encourages people to engage with those who are personally unfamiliar and different and to cooperate for mutual benefit (Brooks, 2005; Sønderskov, 2009).

Why, then, would perceived polarization undermine Americans’ trust in each other? Research suggests that generalized social trust is generally lower in societies divided along salient cleavages, such as race, ethnicity, and social class (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2002; Bjørnskov, 2007; Delhey & Newton, 2005; Dinesen & Sønderskov, 2015; Uslaner & Brown, 2005). Whether these divisions are based on racial or economic differences, scholars posit a similar explanation of why they are detrimental to social trust: they decrease the sense of shared values and common belonging among members of society, leaving them feeling less connected with one another (Delhey & Newton, 2005; Rothstein & Uslaner, 2005).

Similarity breeds trust, as people are naturally inclined to trust those with similar attitudes and values (Byrne, 1961). The belief that fellow citizens share common values fosters trust and allows this trust to be generalized to society as a whole (Offe, 1999). In fact, social trust is higher when there is more agreement than disagreement among citizens on key values, such as the role of government and moral issues (Beugelsdijk & Klasing, 2016; Rapp, 2016).

Dissimilarity and discord, conversely, engender feelings of mistrust. Studies have shown the significance of actual and perceived social divisions in fueling distrust (Delhey & Newton, 2003). The greater the perceived divisions over core values regarding how society should function, the less likely individuals are to feel that they belong to the same “community” (Delhey & Newton, 2005). Tensions arising from such differences render it difficult to promote social trust, especially if divisions are salient.

Political polarization is a form of social division not previously examined in relation to Americans’ social trust. While past research has explored the role of social divisions based on racial/ethnic, economic, and cultural grounds in eroding social trust, the rise of political polarization warrants the need to investigate whether political divisions have similar adverse effects. Specifically, this study focuses on the public perception of polarization as an indicator of social division and examines whether it undermines social trust.

Some might say that perceived polarization should have little net effect on social trust if it is guided by political group identity; that is, to the extent that it decreases one’s trust in those with different political views, its impact could be offset by it increasing one’s trust in those who are politically similar. I argue, however, that this may not be the case. First, trust in most people, i.e., generalized social trust, does not necessarily indicate how much one trusts people of a particular group, i.e., ingroup-outgroup trust. Since generalized social trust extends to those without similar backgrounds, there is some overlap with outgroup trust, in that both have to do with how one views unfamiliar and dissimilar others.

Nonetheless, social trust and group-based trust are different concepts; outgroup trust is based on group identity and thus directed at particular outgroup members, whereas the targets for generalized social trust are much broader (Freitag & Bauer, 2013). Generalized social trust is not about any particular social/political group. Rather, it is an abstract attitude toward others in general, i.e., the “average” person in the population (Robinson & Jackson, 2001).

Furthermore, even if perceived polarization allows political identity to influence social trust, there are still several reasons to expect that it could undermine one’s overall level of trust in others regardless of their political backgrounds. Thus, it reduces trust in the average American.

Due to perceived polarization, individuals might become detached from both sides of the political spectrum as they see growing extremism and intolerance on both sides. Most Americans are fed up with polarization in both political parties and the inability to find common ground (More in Common, 2018). This is most likely to be true for Independents, but even for partisans, polarization can make neither side look good. In fact, many party supporters report feeling less warmth toward their own party as polarization has risen (Groenendyk, 2018). They dislike the other party, but many nonetheless seem to disapprove of—or, at least feel ambivalent about—the direction their party is headed, i.e., ideological extremity.

Polarization and extremism conflict with the broadly shared social norms of moderation and compromise deemed positive in American society. Few like to think of themselves as extreme (Hetherington & Rudolph, 2015), and close-mindedness and inflexibility are likewise regarded negatively (Klar & Krupnikov, 2016). But when thinking about the people out there, frequent media coverage of polarization makes people believe that more and more Americans today embrace polarized, extreme, and intolerant views, on both the left and right (Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016b). People tend to view such individuals as typical of the majority of ordinary voters, while considering themselves not like them; further, people express negative views of those espousing extreme and rigid views, not just in the other party but also in their own party (Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016b).

In other words, as people believe typical Americans are becoming more polarized and close-minded, such perceptions should induce feelings of distance and estrangement from fellow citizens and society in general. This can result in the erosion of social trust.

Testing This Relationship: Panel Data Analysis

To test my argument, I use panel survey data containing repeated measures of the same key variables taken on the same individuals. A nationally representative probability sample of U.S. adults was drawn from NORC’s AmeriSpeak Panel and interviewed yearly from 2016 to 2020. My study sample consists of 1337 panel members present in all five waves. It closely mirrors the demographics of the national population (see Online Appendix, Table A1).

In every wave, respondents answered three standard questions on generalized social trust: whether they think most people can be trusted (vs. can’t be too careful), try to be helpful (vs. mostly look out for themselves), and try to be fair (vs. take advantage of someone). Each question was asked in a dichotomous-choice format, and positive responses were summed into a four-point index, with higher values corresponding to higher social trust (see Online Appendix for survey instrument).

Perceived polarization was measured by asking respondents to indicate the extent to which they think Americans these days are politically divided and polarized, disagree on issues, and have extreme views. Responses were combined into an index, where higher values indicate higher levels of perceived polarization. By asking about the American public specifically, these questions provide a good measure for this study, which seeks to understand the effect of perceptions of mass-level polarization rather than polarization among political elites. Overall, there is a significant increase in mean perceived polarization over the five-year study period (see Online Appendix, Fig A1).

For the analysis, I used fixed-effects panel models, focusing on change within individuals over time. Fixed-effects models discard all between-unit variation and utilize only within-unit variation (Wooldridge, 2010). Each person is compared to him- or herself at different time points, so any stable individual-specific characteristics—observed and unobserved—are automatically controlled for, under the assumption that their effects are constant over time. Since they offer controls for all time-invariant individual heterogeneity, which usually makes up a substantial proportion of confounding, fixed-effects models are considered superior to other approaches for estimating causal effects with nonexperimental data (Allison, 2009).

To use fixed-effects models, the data should ideally contain considerable within-unit variation in the predictor to leverage estimation of the effects. My data do so; the level of perceived polarization varies substantially from wave to wave at the individual level. Across the five waves, 98.2% of respondents changed their perceptions of polarization at least once. Such extensive variation within individuals makes it appropriate to employ fixed-effects models.

Since these models control for all stable confounders, one does not need a list of respondent background variables, e.g., demographics, to serve as “control variables.” However, the models do not automatically eliminate confounding due to variables that change over time and correlate with both independent and dependent variables. Therefore, I accounted for several potential time-varying confounders. Among these was a measure of changes in personal finances, based on past research showing the associations of personal economic well-being with social trust and with perceived polarization. Next, I included controls for changes in the perceived prevalence of discrimination against one’s gender and racial groups, since experiencing or witnessing discrimination negatively impacts generalized social trust (Douds & Wu 2018) and could also contribute to perceptions of polarization, if a given identity is politically relevant.

To isolate the independent effects of perceived polarization from actual polarization, I controlled for changes in the intensity of individual political preferences, such as increased extremity of issue attitudes, partisan and ideological identities, and affect toward Donald Trump.1 By controlling for these correlates and potential confounders, I can assess whether perceived polarization plays a role in the erosion of generalized social trust.2

Finally, I included dummy variables representing each wave to account for common time trends. They capture the average effects of unobserved temporal influences on social trust in each wave. I estimated the following fixed-effects model:

where indexes individual respondents and indexes survey waves, is a vector of time-varying controls, and are individual and time fixed effects, respectively, and is an idiosyncratic error term.

Effect of Perceived Polarization on Social Trust

Table 1 reports the results of the fixed-effects estimations. Model 1 serves as a baseline model, estimating the effect of perceived polarization on generalized social trust with individual and time fixed effects. Model 2 includes the time-varying control variables.

Table 1.

Effect of perceived polarization on generalized social trust: fixed-effect estimates

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Changes in | ||

| Perceived polarization | − 0.096** | − 0.087* |

| (0.035) | (0.037) | |

| Changes in | ||

| Personal financial situation | − 0.101*** | |

| (0.023) | ||

| Issue attitude extremity | − 0.067 | |

| (0.041) | ||

| Intensity of affect toward Donald Trump | − 0.035 | |

| (0.022) | ||

| Partisan strength | 0.017 | |

| (0.029) | ||

| Ideological strength | − 0.014 | |

| (0.022) | ||

| Perceived discrimination against own gender | − 0.029 | |

| (0.034) | ||

| Perceived discrimination against own race | 0.020 | |

| (0.032) | ||

| Wave 2 (2017) | 0.039** | 0.032* |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| Wave 3 (2018) | 0.018 | 0.016 |

| (0.013) | (0.015) | |

| Wave 4 (2019) | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| (0.014) | (0.016) | |

| Wave 5 (2020) | − 0.007 | − 0.012 |

| (0.013) | (0.014) | |

| Constant | 0.525*** | 0.634*** |

| (0.026) | (0.046) | |

| N of observations | 6651 | 6167 |

| N of individuals | 1336 | 1237 |

Note: Results from linear fixed-effects panel models. Robust standard errors in parentheses. All variables rescaled to range from 0–1. Weighted to represent the U.S. adult population. Unweighted estimates are very similar (see Online Appendix, Table A2)

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

In Model 1, perceived polarization significantly reduces social trust, after controlling for person-specific fixed effects and common time trends (p < 0.01). That is, increases in perceived polarization result in decreases in trust in others. Even after adding time-varying control variables in Model 2, the negative effect of perceived polarization persists (p < 0.05).

It is worth emphasizing that the results are robust to controlling for actual ideological and affective polarization. In fact, the variables related to actual polarization, i.e., increases in issue attitude extremity, intensity of like/dislike for Trump,3 and strength of partisanship and ideology, are statistically insignificant. In other words, adopting more extreme attitudes and feelings does not significantly impact one’s social trust, while perceiving greater polarization within society does. These results are consistent with those of Enders and Armaly (2019), which show that perceived polarization has its own significance, independent of actual polarization.

One might speculate about whether perceived polarization potentially mediates the relationship between actual polarization and social trust. For instance, adopting more extreme attitudes might enhance perceptions of polarization, which then negatively affect social trust. Alternatively, actual polarization might mediate the effect of perceived polarization, if an impression of greater polarization makes people more extreme in their own attitudes, and then it reduces their social trust. While these are interesting questions, they cannot be directly tested from this data because the estimates will likely be biased (see Bullock et al., 2010).4 Regardless, the results demonstrate that perceived polarization has a significant, direct effect on social trust.

The largest effect comes from changes in personal economic conditions, a factor known to impact generalized social trust; the less satisfied individuals are financially, the less trusting they become (p < 0.001). Other changes, such as a perception of increased discrimination toward one’s own social groups, do not have significant effects.

Based on my models, perceived polarization reduces social trust by 8.7 to 9.6 percentage points, as it changes from the lowest (0) to the highest (1) level. However, not many people would experience such a drastic change over five years. To assess its substantive effect more realistically, I used the actual range of shift observed within individuals (see Mummolo & Peterson, 2018). During the study period, the average within-person change in perceived polarization over time is 0.28 on a 0–1 scale; based on this shift, as one’s perception of polarization changes (increases) by the mean within-person range, social trust decreases by 2.4–2.7 percentage points. An increase in perceived polarization by one standard deviation of the within-person distribution (0.19) produces a 1.7–1.8 percentage point decrease in social trust. These effect sizes are similar to those found in previous studies on other forms of division, such as those based on income or race/ethnicity.5

Discussion

Perceived polarization implies that people are less likely to believe that Americans share common values and interests. As a result, they should find it difficult to feel bound to each other and develop social trust. Using fixed-effects models that control for all stable individual heterogeneity, common time trends, and several time-varying confounders, I find support for my hypothesis that perceived polarization erodes social trust.

My fixed-effects estimates represent the average treatment effect on the treated because these estimates are based only on information from those whose perceptions of polarization changed over time, i.e., those who were “treated.” The generalizability of the fixed-effects results is thus limited to those experiencing such change in treatment status. Recall that my data include a nationally representative sample, and almost all respondents’ perceptions of polarization changed across waves. Only 1.8% showed no within-individual variation whatsoever. Given this general tendency of within-individual changes in the level of perceived polarization, the effects I find should apply broadly throughout the population.

Note that at the beginning of the study in 2016, the level of public perception of polarization was already high. However, even after seemingly reaching a plateau, perceived polarization continued to rise. For example, 83.7% of my respondents said in 2016 that Americans were “very” or “extremely” divided, which increased to 85.3% in 2020. Similarly, 80.7% saw “very little” or “no agreement” on issues among Americans in 2016, and 84.8% did so in 2020. In other words, perceived polarization still increased significantly, albeit moderately, during these years, and that affected Americans’ social trust.

The talk of polarization is not new. Political polarization started to rise in Congress in the late 1970s (McCarty et al., 2008). The mass public began to show signs of affective polarization in the late 1980s, although it was only after 2000 that this trend accelerated (Iyengar & Krupenkin, 2018). The public’s perception of political polarization coincided with these trends; in 2001, 24% of Americans said the country was greatly divided, and that number drastically increased thereafter, to 53% in 2004 and 77% in 2016 (Gallup, 2017).

If I extrapolate these findings back in time, I might find a much larger effect of perceived polarization. Over the last few decades, the American public has witnessed constant partisan conflict and rancor, with the media telling them on a daily basis that the country is polarized. So, by the year 2016, public perceptions of polarization were already high, with little room to grow further. If we could go back in time some 20 years, to when people started to notice and develop perceptions of a polarized America, the negative effects of perceived polarization on social trust might be even stronger and much more pronounced than those found here.

Finally, one limitation of this panel analysis is that fixed-effects models are not well suited to dealing with reverse causality, especially if one expects contemporaneous effects.6 Reverse causation is possible, to the extent that people whose social trust level is lowered (for reasons unrelated to perceived polarization) would perceive greater divisions within society, including the political kind. Using experiments will help rule out reverse causation.

Experimental Evidence

To establish the causal effects of perceived polarization on social trust, I now use an experimental design in which I manipulate perceived polarization and assess its impact on social trust levels. My experiment aims to complement the panel study findings in two additional ways. First, besides the standard three-item generalized social trust scale, I include two more measures based on alternative operationalizations of social trust: (1) trust in personally unknown individuals, and (2) trust in the American citizenry. Second, I examine the behavioral implications of reduced social trust as a result of perceived polarization. Advocates of social trust emphasize its role in promoting prosocial behaviors—behaviors that benefit others, such as helping and cooperating (Brooks, 2005; Sønderskov, 2009; Uslaner, 2002). To what extent, then, does perceived polarization discourage socially beneficial behavior, i.e., prosocial actions?

Using multiple operationalizations of social trust not only improves reliability but also sheds clearer light on what trusting other members of society actually means. For instance, generalized social trust has been found to correspond to trust in people one meets for the first time (Torpe & Lolle, 2011), but the fairly abstract wording of the standard trust scale makes it difficult to assess how much one would actually trust a stranger, and in what situations. Therefore, I include a measure focused on people’s behavioral willingness to trust strangers in everyday situations.

Furthermore, generalized social trust has been defined as trust in fellow citizens because social trust is believed to reflect the quality of a society’s social structure (Coleman, 1988). Nonetheless, when asked about “most people” by the standard question, some people seem to base their answers on their opinions about non-nationals (Sturgis & Smith, 2010). To avoid this ambiguity, I also include items to measure the trust one has in co-nationals, particularly tapping into positive expectations about other Americans’ civic and social behavior.

These measures cover important aspects of social trust for the smooth functioning of society. First, beliefs about strangers govern human interactions in modern societies, where people rely on strangers in various everyday activities, e.g., when buying from or hiring an individual, or when sharing a ride or space with a stranger. Additionally, beliefs about the character of a typical citizen influence whether one sees it as fair to comply with society’s norms and contribute to society, such as working toward the common good and reciprocating prosocial acts (Putnam, 2000).

As for the behavioral consequences of perceived polarization, I explore how it affects cooperation for charitable causes. People give to charity for various reasons, including inherent kindness, personal satisfaction, and connection with a charity or cause (Andreoni, 1989; Bennett, 2003). Importantly, social trust is a powerful driver of giving (Uslaner, 2002) and cooperation for collective welfare (Sønderskov, 2009). People high (vs. low) in social trust are more likely to act prosocially because they have positive expectations of the reciprocity of goodwill by others (Putnam, 2000). In the following experiment, I present to the respondents charitable giving as a form of cooperation with other Americans and see whether it is affected by perceptions of polarization. If perceived polarization reduces one’s social trust, it should also negatively affect one’s willingness to act prosocially and cooperate.

Procedures, Treatments, and Measures

I recruited a sample of 1006 Americans from an online survey panel, Bovitz Inc.’s Forthright, in spring 2020. My sample resembles the demographic distribution of the American population (see Online Appendix, Table A6). Respondents were randomly assigned to read one of three news articles designed to either promote perceived polarization (more-polarization), reduce perceived polarization (less-polarization), or serve as a control article (see Online Appendix for treatments). The treatments were developed through pretests to improve their effectiveness in manipulating levels of perceived polarization. The article for the more-polarization condition portrayed the American people as severely polarized, highlighting deep divisions with little middle ground. On the other hand, the less-polarization treatment portrayed Americans as sharing substantial common ground, rejecting extremism, and being open to compromise.

The control article included no reference to polarization. It discussed the COVID-19 pandemic and its expected electoral impact in the most politically neutral manner possible. I chose this political control over a non-political control to ensure that my treatment effect is attributable to differences in the level of polarization perceived by individuals, not merely differences in the salience of politics. All respondents were shown articles about U.S. politics, with the only difference being whether/how they addressed the topic of polarization—highly polarized, not polarized, or without any discussion of polarization. I can thus assess the implications of different levels of perceived polarization on social trust, while keeping constant the effects of priming politics.

For outcome measures, I first asked respondents the three standard questions on generalized social trust. To measure trust in the American citizenry, I used questions adapted from past research (Pew Research Center, 2019b) about how much respondents trust Americans to act as honest and responsible citizens, such as by treating each other with honesty, obeying laws, reporting their income honestly, and working together to solve problems (see Online Appendix for questionnaire). Additionally, I measured willingness to trust strangers in everyday situations by assessing respondents’ comfort levels with buying used items from Craigslist, giving a ride, and lending their cellphone to a stranger. Three indices of social trust were created, with higher values indicating higher trust.

To obtain a behavioral measure that reflects social trust, I focused on people’s decisions about charitable donations and how they were brought into cooperation. At the end of the study, respondents were given a cash bonus of $2.00 each and told that they could keep the bonus or give any or all of it to a charity. They were shown a list of four well-known, non-partisan charitable organizations and asked to allocate their bonus between themselves and the charity.

For this task, respondents were further randomized into either the baseline or donation-matching condition. In the baseline condition, they were simply asked to individually decide how much to give and how much to keep. For the donation-matching condition, respondents were told that people across the country were participating in this study and their contributions would be matched if more than 80% of the respondents donated as well, regardless of the amount. They were specifically asked to take this into account in their decisions.

The purpose of this matching offer was to frame donation as an act of cooperation with other citizens and to encourage respondents to make decisions based on their expectations of others’ behavior. To the extent that perceived polarization lowers social trust, this offer should be less appealing to those with lower trust or lower expectations of others’ cooperation. Conversely, people should be more willing to contribute if they believe that most people are going to participate enough to make the matching threshold attainable, which is more likely among those whose social trust has improved.

Manipulation Check

Respondents were asked after treatment the same four questions measuring perceived polarization as in the panel study (e.g., perceived political divisions, polarization, attitude extremity, and disagreement among voters). I added a question on the perceived intensity of partisan animosity. These five items provide a more holistic measure that covers perceptions of both ideological and affective polarization.

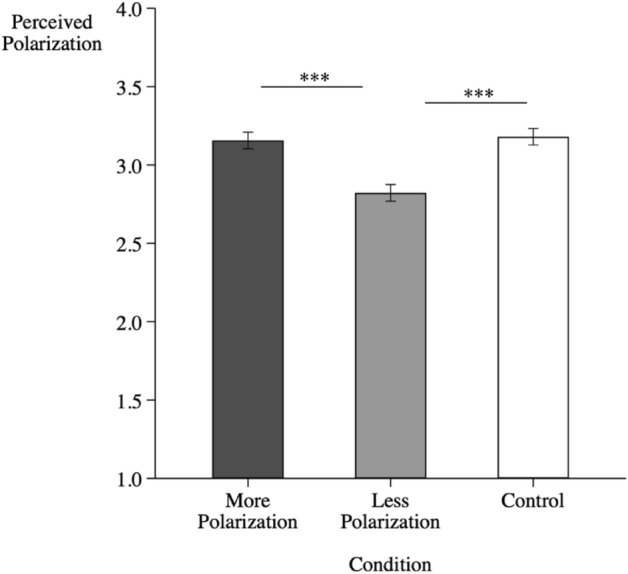

Ideally, the treatments should manipulate perceived polarization in both higher and lower directions. Unfortunately, they succeeded only in decreasing perceptions of polarization, not in increasing them. In Fig. 1, the less-polarization condition is significantly lower in perceived polarization than the more-polarization and control conditions (both p < 0.001). However, there is no difference between the means of the more-polarization and control conditions (p = 0.53).7 This is a somewhat anticipated possibility, given the already high level of perceived polarization; most Americans already believe the country to be polarized, so it may have been difficult to experimentally raise people’s perceptions of polarization any further.

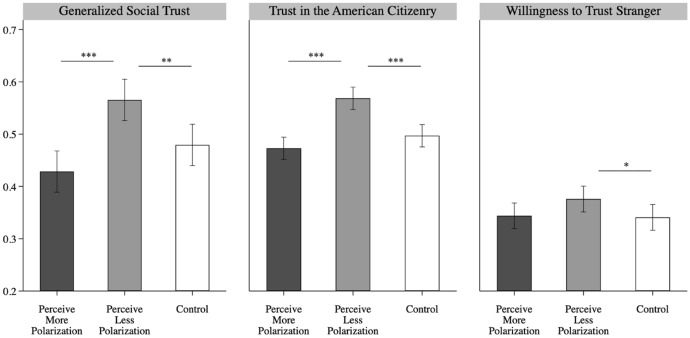

Fig. 1.

Manipulation Check: Perceived Polarization by Condition Note: Mean perceived polarization scores, with 95% confidence intervals. Range from 1 (low) to 4 (high)

Effect of Perceived Polarization on Social Trust Measures

To test my hypothesis, I compared the means of each social trust measure across the three conditions, testing for differences between the less-polarization and control conditions and between the less-polarization and more-polarization conditions. These comparisons will reveal the difference in social trust levels when perceived polarization is high versus when it is decreased. To improve the efficiency of the analysis, I included several covariates known to be strongly related to social trust, including household income, age, and indicators of minority identity/status (e.g., female, non-white), lower educational attainment, and divorce or separation (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2002; Brehm & Rahn, 1997; Uslaner, 2002).

If my predictions hold, I should find lower levels of generalized social trust, trust in the American citizenry, and willingness to trust strangers in the more-polarization and control conditions, and higher levels in the less-polarization condition. As for the behavioral measure, by depicting the donation task as cooperation with others, the matching offer should increase giving among people whose social trust and expectations about others’ behavior are likely be improved by treatment, i.e., those in the less-polarization condition.

As Fig. 2 shows, the results provide strong support for my hypothesis. Trust is significantly lower in the conditions where perceptions of polarization remain high. Trust increases when those perceptions are reduced. In the left panel, generalized social trust is highest in the less-polarization condition, 8.6% points higher than the control (p < 0.01), and 13.7 percentage points higher than the more-polarization condition (p < 0.001). The middle panel shows the mean levels of trust in the American citizenry by condition. Again, trust is lower when perceived polarization is high, but the treatment to reduce perceived polarization increases people’s trust in other Americans, by 7.2 percentage points over the control and by 9.6 percentage points over the more-polarization treatment (both p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Effect of Perceived Polarization Treatments on Social Trust Measures Note: Estimated means of social trust, with 95% confidence intervals. All outcomes scaled from 0 (low) to 1 (high trust). Means adjusted for covariates

Perceived polarization also impacts individuals’ willingness to place trust in strangers in everyday situations. The means are in the hypothesized directions; the right panel of Fig. 2 shows that people in the less-polarization condition are most trusting, with a mean trust 3.5% points higher than the control condition (p < 0.05). Trust is also higher than the more-polarization condition (by 3.2% points), but the difference is only marginally significant (p = 0.07).

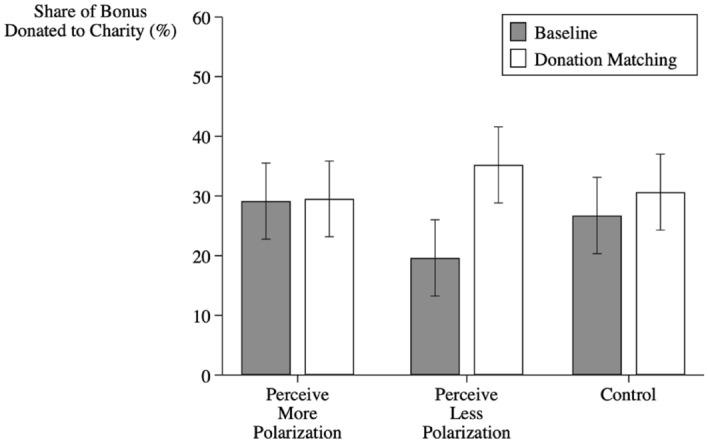

Finally, I assessed whether perceived polarization influences prosocial, cooperative behavior. For the donation task, I have two between-subjects factors: perception of polarization (more, less, or control) and donation matching (or no matching). To the extent that the polarization treatment affects social trust, the matching offer should boost donations among those in the less-polarization condition, thus producing an interaction effect.

I compared the mean percentages of the bonus donated to charity across conditions. First, the analysis reveals no main effect of perceived polarization treatment; the mean rate of giving does not significantly differ between the more-polarization, less-polarization, and control conditions (p = 0.84). But donation matching has a significant main effect: people gave more when an offer was made to match their donations than when no such offer was made (p < 0.05).

Second, as predicted, there is a significant interaction between perceived polarization treatments and donation matching (p < 0.05). Importantly, Fig. 3 reveals that the effect of the matching offer is mostly concentrated among people in the less-polarization condition. The offer did not make much difference for those in the other two conditions, where perceptions of polarization remained high. By contrast, people whose perceived polarization was reduced were more interested in combining forces with others to support charitable causes, when such an opportunity was present. Presenting giving as a cooperative activity and prompting people to think about the likely behavior of others caused a significant increase in donations, only for those in the less-polarization condition, i.e., those whose social trust had been improved (p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Giving by Perceived Polarization Treatments and Donation Matching Condition Note: Estimated mean percentages of giving, with 95% confidence intervals. Means adjusted for covariates

A Note on the Mechanism

Experiments provide an unbiased estimate of the causal treatment effect. The question, however, remains: what is the causal mechanism linking perceived polarization to social trust? When outlining my hypothesized effects, I drew on the literature suggesting that divisions in society make people see less commonality with one another and thus fuel distrust, whereas the belief that similar values are shared fosters social trust (Delhey & Newton, 2005; Rothstein & Uslaner, 2005).

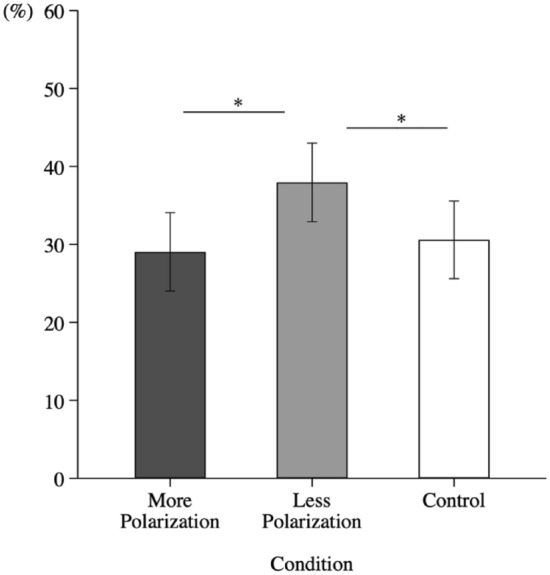

To explore this question, I asked respondents after treatment how many Americans (e.g., none, few, some, about half, most, almost all, all) they thought shared their values or beliefs. If perceived polarization reduces social trust by lowering the sense of shared values, people with high perceived polarization should report lower levels of perceived commonality than those whose perceptions of polarization have been reduced.

That is precisely what my data show: in Fig. 4, those in the less-polarization condition are more likely to say that at least most people in this country share similar values and beliefs than those in the more-polarization and control conditions, respectively (both p < 0.05). Certainly, this is not a mediation analysis and does not establish this is how the effect of perceived polarization occurs. Still, this finding provides insight into the possible mechanisms at work.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of People Saying that Most, Almost, All, or All Americans Share Their Values or Beliefs, by Condition

Discussion

My experiment provides strong evidence for the causal effects of perceived polarization on social trust. Consistent with my predictions, perceptions of polarization lead to different levels of trust in generalized others, trust in fellow citizens to do the right thing, and willingness to trust unfamiliar others in everyday situations.

Perceived polarization also impacts individual behavior associated with contributing to the common good, an important form of collective action. When donation to a charity was described as cooperation with other citizens, the rate of donation was highest among those whose perceived polarization was reduced, i.e., those whose belief in the goodwill of others was likely to have increased as a result. All the charities listed pursue public-good causes that benefit members of society at large. The matching offer made people reflect on whether most people would cooperate for the interests of the larger population, and those with improved social trust were most likely to cooperate and contribute.

Studies suggest that the offer to match donations does not itself automatically boost contributions (e.g., Huck & Rasul, 2011). What matters is one’s belief about the actions of others, which is the essence of social trust. Especially given an offer to match donations conditional on meeting a certain threshold of joint participation, such as the one used here, people take into account the likely behavior of others when deciding whether to donate or not (see Gee & Schreck, 2018). My results demonstrate that perceptions of polarization play a consequential role in conditioning individual behavior for collective action and in society’s ability to produce charitable public goods.

Social trust is an “abstract preparedness to trust” others in general, extending beyond the boundaries of face-to-face interaction and personal settings (Stolle, 2002, p. 403). In large, modern societies that depend greatly on interactions between strangers, social trust makes it easier for individuals with little personal familiarity to collaborate for productive exchange.

The scenarios asked about in my experiment, such as buying used items from someone online, riding with strangers, or lending goods to strangers, all tap into how comfortable one feels engaging with strangers in real-world contexts. Importantly, these contexts have close relevance to the activities that constitute the so-called “sharing economy,” a rapidly growing market phenomenon in which access to goods and services is shared or exchanged between individuals, e.g., ride sharing, house sharing, trading, reselling, and freelance sourcing.

Social trust is fundamental to these kinds of exchanges and interactions. People must trust the platforms connecting users, but more importantly, they must trust each other. My study finds that people who perceive high polarization are more suspicious of strangers and will thus be less inclined to participate in these sharing and collaborative activities. This underlines the potentially far-reaching consequences of perceived polarization, including economic implications, and more broadly, the potential for socioeconomic collaboration.

My experiment is not without limitations. One is the inability to increase perceptions of polarization, possibly due to the ceiling effect. Future research could use stronger manipulations, but given the high level of perceived polarization established in the public’s minds, this may not be an easy task to accomplish. However, this experiment still offers a good test for identifying the causal effects of perceived polarization. Due to random assignment and the successful manipulation of significantly lowering perceptions of polarization, any difference in social trust measures between the less-polarization condition and the other two conditions is attributable to different levels of perceived polarization—whether they are high, as is the case for most Americans today, or lowered. Furthermore, people in the more-polarization condition, whose perception of polarization was unchanged, behaved very similarly to those in the control condition; if their social trust levels had been different from those in the control, it would have indicated that something other than perceptions of polarization was responsible for the observed results. The fact that the more-polarization treatment neither shifted perceived polarization nor affected any of the outcome measures relative to the control bolsters my argument: perceptions of polarization cause changes in social trust.

Conclusion

Both of my panel survey and experimental results show that perceived polarization makes people less trusting of each other. Past research has documented the similar effects of social divisions based on racial/ethnic and economic differences, but my study provides new evidence that political divisions matter. More precisely, this study is the first to demonstrate that perceptions of political divisions can directly undermine Americans’ social trust. Perceived polarization has an effect independent of actual polarization, and its consequences reach further than previously recognized in the literature. Since the public is expected to maintain perceptions of a polarized country (Pew Research Center, 2019a), the adverse effects of perceived polarization on social trust are likely to prevail.

Perceived polarization changes how one views other members of society. In particular, it affects individuals’ judgments about the moral character of their fellow citizens, which in turn influence their willingness to respect social norms and do good for society. Social trust is a belief in the expected actions of others and the expected consequences of others’ actions for our own well-being (Offe, 1999). Trusting others to act as honest and responsible citizens is important because it can affect one’s own behavior. In fact, the more trusting one is, the more likely they are to behaves as a good citizen themselves (Putnam, 2000; Uslaner, 2002).

Perceived polarization and the erosion of social trust present challenges for social cohesion. Low social trust may discourage people from doing good deeds and voluntarily contributing to society. If people believe that others cannot be trusted to do the right thing, they will be less willing to forgo their self-interests in favor of the collective. Social trust entails an expectation that others will do what is right and act for the common good (Neilson & Paxton, 2010). Why would anyone make a sacrifice for the common good if they believe others would not follow suit and would instead take advantage of their good behavior? They may become more concerned with looking out for themselves than caring for the collective interest.

Today, this question seems more important than ever. Besides the COVID-19 pandemic, the country is faced with a number of national challenges, including climate change, inequality, public health, etc., which require cooperation and collective action among citizens. If the public does not trust each other to do the right thing and is unwilling to put aside personal interests for the common good, the country will find it harder to achieve collective goals.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Diana Mutz, Matthew Levendusky, Yphtach Lelkes, Michael Delli Carpini, Michele Margolis, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. I am grateful to the Institute for the Study of Citizens and Politics (ISCAP) at the University of Pennsylvania for providing me with access to their panel survey data.

Data availability

Replication data and code are available at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WXOYVM

Footnotes

These measures were created by folding the original scales at their midpoints, so higher values indicate greater extremity/polarization. See Online Appendix for details on variable construction.

To preserve cases, missing values in control variables were recoded to the neutral midpoint. The results do not change with these cases included or excluded.

Affective polarization was measured using a feeling thermometer for Donald Trump because this item was available in all five waves. The farther the rating moves from the neutral 50-degree, the more intense the feeling is. Affective polarization is more commonly measured via feeling thermometers for the Democratic and Republican parties, but these items were not asked in every wave. When I analyze a subset of the data that includes party thermometer ratings, perceived polarization still significantly reduces social trust after controlling for the actual polarization of party affect and issue attitudes. See Online Appendix, Table A3.

When I nonetheless explore the data for these questions, the coefficients of the actual polarization are unaffected by whether or not the model includes the perceived polarization variable, and they are consistently statistically insignificant. There is thus little indication for perceived polarization being a potential pathway mediating the relationship between actual polarization and social trust. On the other hand, the model predicts a larger effect of perceived polarization on social trust when the actual polarization variables are not included; when they are, the effect of perceived polarization decreases by 8.4% (see Online Appendix, Table A4). This might indicate the presence of partial indirect effects but cannot be confirmed with this data.

My effect sizes cannot be directly compared to those from past studies, but just for reference, studies report that an increase by one standard deviation in racial/ethnic fragmentation or income inequality decreases social trust by 0.6–3.0 percentage points (Alesina and La Ferrara 2002; Dinesen and Sønderskov 2015).

See Online Appendix, Table A5 for the cross-lagged panel regression results.

Some might wonder if this has to do with the content of the control article—the pandemic and the election. Since these were polarizing topics, mentioning them even in a neutral manner might have had a similar effect to the more-polarization treatment. Yet, while developing my treatments, I also tested an apolitical stimulus to see if it would serve a better baseline/control. The more-polarization treatment still did not induce higher perceived polarization relative to the apolitical control condition. This suggests the presence of ceiling effects. See Online Appendix for pretest results.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahler DJ. Self-fulfilling misperceptions of public polarization. Journal of Politics. 2014;76(3):607–620. doi: 10.1017/S0022381614000085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A, La Ferrara E. Who trusts others? Journal of Public Economics. 2002;85(2):207–234. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00084-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Fixed effects regression models. SAGE Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J. Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and ricardian equivalence. Journal of Political Economy. 1989;97(6):1447–1458. doi: 10.1086/261662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. Factors underlying the inclination to donate to particular types of charity. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing. 2003;8(1):12–29. doi: 10.1002/nvsm.198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk S, Klasing MJ. Diversity and trust: The role of shared values. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2016;44(3):522–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2015.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnskov C. Determinants of generalized trust: A cross-country comparison. Public Choice. 2007;130(1–2):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11127-006-9069-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm J, Rahn W. Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science. 1997;41(3):999–1023. doi: 10.2307/2111684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AC. Does social capital make you generous? Social Science Quarterly. 2005;86(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.0038-4941.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock JG, Green DP, Shang EH. Yes, but what’s the mechanism? (Don’t expect an easy answer) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(4):550–558. doi: 10.1037/a0018933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne D. Interpersonal attraction and attitude similarity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1961;62(3):713–715. doi: 10.1037/h0044721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl Noah, Billari Francesco C. Generalized trust and intelligence in the United States. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrin J. Comment: The political relevance of trust in government. American Political Science Review. 1974;68(3):973–988. doi: 10.2307/1959141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–120. doi: 10.1086/228943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delhey J, Newton K. Who trusts? The origins of social trust in seven societies. European Societies. 2003;5(2):93–137. doi: 10.1080/1461669032000072256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delhey J, Newton K. Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: Global pattern or nordic exceptionalism? European Sociological Review. 2005;21(4):311–327. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delhey J, Newton K, Welzel C. How general is trust in ‘most people’? Solving the radius of trust problem. American Sociological Review. 2011;76(5):786–807. doi: 10.1177/0003122411420817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesen PT, Sønderskov KM. Ethnic diversity and social trust: Evidence from the micro-context. American Sociological Review. 2015;80(3):550–573. doi: 10.1177/0003122415577989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douds K, Jie Wu. Trust in the bayou city: Do racial segregation and discrimination matter for generalized trust? Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 2018;4(4):567–584. doi: 10.1177/2332649217717741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders AM, Armaly MT. The differential effects of actual and perceived polarization. Political Behavior. 2019;41(3):815–839. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-9476-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M, Bauer PC. Testing for measurement equivalence in surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2013;77(S1):24–44. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. Trust: Human nature and the reconstitution of social order. Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. (2017). The divided states of America. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/201728/divided-states-america.aspx

- Gee LK, Schreck MJ. Do beliefs about peers matter for donation matching? Experiments in the field and laboratory. Games and Economic Behavior. 2018;107:282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendyk E. Competing motives in a polarized electorate: Political responsiveness, identity defensiveness, and the rise of partisan antipathy. Political Psychology. 2018;39:159–171. doi: 10.1111/pops.12481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington M, Rudolph TJ. Why Washington won’t work: Polarization, political trust, and the governing crisis. University of Chicago Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huck S, Rasul I. Matched fundraising: Evidence from a natural field experiment. Journal of Public Economics. 2011;95(5–6):351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S, Krupenkin M. The strengthening of partisan affect: Strengthening of partisan affect. Political Psychology. 2018;39:201–218. doi: 10.1111/pops.12487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaase M. Interpersonal trust, political trust and non-institutionalised political participation in Western Europe. West European Politics. 1999;22(3):1–21. doi: 10.1080/01402389908425313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keele L. social capital and the dynamics of trust in government. American Journal of Political Science. 2007;51(2):241–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00248.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klar Samara, Krupnikov Yanna. Independent politics: How American disdain for parties leads to political inaction. Cambridge University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knack S. Social capital and the quality of government: Evidence from the States. American Journal of Political Science. 2002;46(4):772. doi: 10.2307/3088433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knack S, Keefer P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997;112(4):1251–1288. doi: 10.1162/003355300555475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levendusky MS, Malhotra N. Does media coverage of partisan polarization affect political attitudes? Political Communication. 2016;33(2):283–301. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2015.1038455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levendusky MS, Malhotra N. (Mis)Perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2016;80(S1):378–391. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfv045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty N, Poole KT, Rosenthal H. Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. The MIT Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- More in Common. (2018). “Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape.” https://hiddentribes.us/pdf/hidden_tribes_report.pdf

- Mummolo J, Peterson E. Improving the interpretation of fixed effects regression results. Political Science Research and Methods. 2018;6(4):829–835. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2017.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson LA, Paxton P. Social capital and political consumerism: A multilevel analysis. Social Problems. 2010;57(1):5–24. doi: 10.1525/sp.2010.57.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K. Trust, social capital, civil society, and democracy. International Political Science Review. 2001;22(2):201–214. doi: 10.1177/0192512101222004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Offe Claus. How can we trust our fellow citizens? In: Mark E, editor. Democracy and trust. Warren. Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 42–87. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton P. Is Social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105(1):88–127. doi: 10.1086/210268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI). (2019). “American Democracy in Crisis: The Fate of Pluralism in a Divided Nation.”https://www.prri.org/research/american-democracy-in-crisis-the-fate-of-pluralism-in-a-divided-nation

- Pew Research Center. (2019a). “Looking to the Future, Public Sees an America in Decline on Many Fronts.”https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/03/21/public-sees-an-america-in-decline-on-many-fronts/

- Pew Research Center. (2019b). “Trust and Distrust in America.”https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/07/22/trust-and-distrust-in-america/https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/07/22/trust-and-distrust-in-america/

- Pew Research Center. (2020). “Far More Americans See 'Very Strong' Partisan Conflicts Now Than in The Last Two Presidential Election Years.” https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/04/far-more-americans-see-very-strong-partisan-conflicts-now-than-in-the-last-two-presidential-election-years/

- Putnam RD. Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern italy. Princeton University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of american community. Simon & Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp C. Moral opinion polarization and the erosion of trust. Social Science Research. 2016;58:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeskens T. But who are those ‘most people’ that can be trusted? evaluating the radius of trust across 29 European societies. Social Indicators Research. 2013;114(2):703–722. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0169-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RV, Jackson EF. Is trust in others declining in America? An age–period–cohort analysis. Social Science Research. 2001;30(1):117–145. doi: 10.1006/ssre.2000.0692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein Bo, Uslaner EM. All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World Politics. 2005;58(01):41–72. doi: 10.1353/wp.2006.0022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderskov KM. Different goods, different effects: Exploring the effects of generalized social trust in large-N collective action. Public Choice. 2009;140:145–160. doi: 10.1007/s11127-009-9416-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stolle D. Trusting strangers—The concept of generalized trust in perspective. Österreichische Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft. 2002;31(4):397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgis P, Smith P. Assessing the validity of generalized trust questions: What kind of trust are we measuring? International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 2010;22(1):74–92. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edq003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torpe L, Lolle H. Identifying social trust in cross-country analysis: Do we really measure the same? Social Indicators Research. 2011;103(3):481–500. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9713-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner EM. The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner EM, Brown M. Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. American Politics Research. 2005;33(6):868–894. doi: 10.1177/1532673X04271903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Setten M, Scheepers P, Lubbers M. Support for restrictive immigration policies in the European Union 2002–2013: The impact of economic strain and ethnic threat for vulnerable economic groups. European Societies. 2017;19(4):440–465. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2016.1268705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall J, Van Boven L, Chambers JR, Judd CM. Perceiving political polarization in the United States: Party identity strength and attitude extremity exacerbate the perceived partisan divide. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(2):145–158. doi: 10.1177/1745691615569849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. The MIT Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Replication data and code are available at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WXOYVM