Abstract

Context

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling is crucial for sex differentiation and development of Leydig and Sertoli cells in fetal mice testes. No such information is available for human embryonic and fetal testes and ovaries.

Objective

To investigate presence and activity of the IGF signaling system during human embryonic and fetal ovarian and testicular development.

Design

Human embryonic and fetal gonads were obtained following legal terminations of pregnancies. Gene expression was assessed by microarray and qPCR transcript analyses. Proteins of the IGF system components were detected with immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses. Specimens were included from 2010 to 2017.

Setting

University Hospital.

Patients/Participants

Ovaries and testes from a total of 124 human embryos and fetuses aged 5 to 17 postconception weeks were obtained from healthy women aged 16 to 47 years resident in Denmark or Scotland.

Main Outcome Measures

Gene expression analysis using microarray was performed in 46 specimens and qPCR analysis in 56 specimens, both sexes included. Protein analysis included 22 specimens (11 ovaries, 11 testes).

Results

IGF system members were detected in embryonic and fetal testes and ovaries, both at gene transcript and protein level. A higher expression of IGF regulators was detected in testes than ovaries, with a preferred localization to Leydig cells.

Conclusions

These data indicate that the IGF system is active during very early gestation, when it may have a regulatory role in Leydig cells.

Keywords: human gonadal development, IGF signaling, stanniocalcins, PAPP-A, first- and second-trimester gonads

The insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling system is a key mediator of cell growth, proliferation, survival, and metabolism throughout the body (1-3). The ligands IGF1 and IGF2 signal through the cell surface IGF receptors type 1 (IGF1R) and the insulin receptor (INSR) (4, 5). Signal transduction is performed by the free ligand and the bioactivity of IGFs is tightly regulated by IGF binding proteins (IGFBP-1 to -6), which antagonize receptor binding but prolong circulatory IGF half-life (6, 7) (Fig. 1).

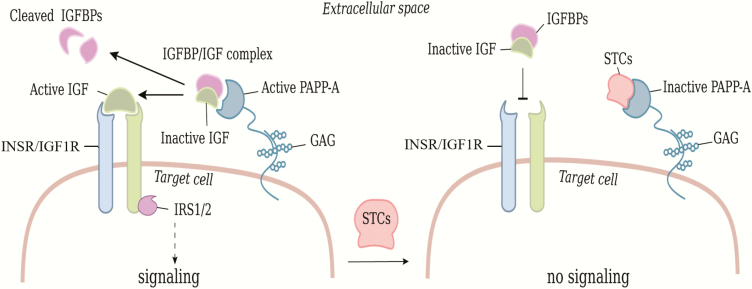

Figure 1.

Regulation of IGF signaling and the inhibitory effects of stanniocalsin (STC). IGFs are tightly regulated by IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) that inhibit receptor binding. PAPPA-A cleaves IGFBPs causing release of bioactive IGF, which binds to the receptors IGF1R or INSR and induces intracellular signaling mediated by IRS1 and IRS2. IGF signaling is downregulated by STCs inhibiting PAPP-A. Abbreviation: GAG, glycosaminoglycan.

IGFs become bioactive when released from their binding proteins by different proteinases, including pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A), which specifically cleaves 3 of the 6 IGFBPs (ie, IGFBP-2, IGFBP-4, and IGFBP-5) and secures release of IGFs in the vicinity of cell surface, close to the receptor (8-10). The proteolytic activity of PAPP-A is inhibited by stanniocalsin-1 and -2 (STC1, STC2), leading to downregulation of IGF signaling (11, 12) (Fig. 1). Information on the IGF system and its impact during embryonic and fetal development is primarily obtained from murine models. Mice deficient in Igf1r or Insr exhibit significant growth retardation and delay in sex differentiation (13, 14). Moreover, sex reversal was observed in XY testes from Igf1r and Insr knockout mice, suggesting that IGF signaling is required for testis differentiation in mice (14, 15). Reduced Sertoli cell proliferation and sperm production occurred when Igf1r and Insr were specifically inactivated in mouse Sertoli cells, emphasizing an important role of IGF signaling in Sertoli cell proliferation and sperm production in mice (16-18). The insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins are key mediators of insulin and IGF signaling, and deletion of Irs2 causes reduced testicular weight and fewer, and abnormal, Sertoli and sperm cells, indicating that Ins2 is vital for murine testicular development (19). Igf1 is expressed in testes of embryonic mice and Igf1 regulates somatic cell proliferation and promotes steroidogenesis, indicating that Igf1 is important for development of the male phenotype and fertility in mice (20, 21). A recent study on spermatogonial stem cells indicated a vital role of Igf1 in mouse spermatogenesis, since it was found to decrease apoptosis of germ cells and increase their density in culture (22).

There is only limited information of the importance of IGF signaling during early development in humans. Neonatal testes show high expression levels of IGF2 and IGF1R in Leydig cells, suggesting that IGF signaling affects Leydig cell differentiation (23). IGF signaling has been reported to be essential for postnatal human testicular descent (24, 25). Expression of IGF2 was decreased in both human testis tissue and ovaries in midterm fetuses (26), although the expression was significantly higher in testes than ovaries. This suggests that IGF2 expression is regulated differently in fetal testes than in ovaries and may exert a more pronounced function in testicular than ovarian development. IGF1 expression has been detected in human fetal ovaries (at 15 and 22 postconception weeks [pcw]) (27), and may affect ovarian function during fetal life. In contrast, IGF2 is the primary ligand operating in adult human ovaries (28). In the adult human ovary, IGF signaling plays a significant role, regulating both folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis (29-32).

In human adult testes, IGF1 has been detected in Sertoli and Leydig cells, and spermatocytes (33, 34). The IGF1R is present on spermatocytes, early spermatids, and variably on Leydig cells, and it may enhance spermatogenesis (33). Furthermore, a positive correlation between IGF1 serum levels and testicular volume has been shown in pubertal boys, suggesting that IGF is involved in testicular growth (18, 35).

The aim of this study was to explore the expression of key regulators of the IGF signaling system in first- and second-trimester human embryonic and fetal gonads of both sexes, at both gene and protein levels. The study focuses on the changes in expression levels over time and the differences between sexes, thereby enhancing knowledge on the IGF signaling system during human gonadal development.

Materials and Methods

This study includes male and female gonads from a total of 124 first- and second-trimester human embryos and fetuses. Gene expression analysis was performed on RNA isolated from 46 embryonic and fetal gonads (18 ovaries, 28 testes) aged 5 to 9 postconception weeks (pcw) (mean ± SD; 7.7 pcw ± 1.1), using a Human Transcriptome Array (HTA) 2.0 microarray analysis (36). Part of the data from the microarray analysis has previously been published (36). The gene expression assays were validated with quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using a total of 56 first- and second-trimester gonads (21 ovaries, 34 testes) aged 5 to 18 pcw. Regulators of the IGF system were detected at protein level using immunohistochemistry in a total of 22 first- and second-trimester gonads (11 ovaries, 11 testes). Ovarian tissue sections with primordial follicles from one human ovary obtained from a 10.5-year-old girl with Fanconi anemia were used for positive controls.

Participating women and ethical statement

Participants were healthy women aged 16 to 47 years (mean age 24.3 years, 95% of the women were between 16 and 41, one woman was 47 years of age) enrolled in Denmark and Scotland, who underwent legal elective terminations of normally-progressing pregnancies under current legislation in each country (ie, in Denmark before 10 pcw, in Scotland before 22 pcw). Women from Denmark were 18 to 47 years of age, and women from Scotland were 16 to 33 years old. All participants received oral and written information about the study and gave their informed consent in writing prior to inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria included dependence on an interpreter, chronic disease, and pregnancies with known disorders. In Denmark, women younger than 18 years were also excluded. Participation had no effect on the medical care received by the women. The study was in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations in Denmark and Scotland and was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee for the Capital Region [KF(01)258206] and NHS Grampian Research Ethics Committees (REC 04/S0802/21, REC 15/NS/0123) respectively. Researchers have no access to patient identifiers and the women undergoing termination of pregnancy were therefore totally anonymized. The ovarian tissue cryopreservation scheme of the 10.5-year-old control patient with Fanconi anemia was approved by the Danish Ministry of Health (J. no. 30–1372) and by the Danish authorities to comply with the European Union tissue directive.

Collection of human embryonic and fetal gonads

Gonadal tissue from first- and second-trimester human embryos and fetuses from 2 separate collections were obtained from 2010 to 2017. In Denmark, embryonic and fetal gonads were obtained following elective surgical terminations of pregnancies at Skejby University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark as described previously (36). Second-trimester medically aborted samples were collected in Aberdeen, Scotland. Details on collection and cohort characteristics have previously been described (37, 38).

Gestational age was in all cases determined by crown-rump length and head circumference for fetuses older than 14 pcw, using abdominal ultrasound. Gonads were identified and isolated using a stereomicroscope directly after the evacuation (Denmark) or dissected from intact fetuses (Scotland). Gonads obtained for gene expression analysis were snap-frozen on dry ice or placed in RNAlater (Sigma-Aldrich, Copenhagen, Denmark) before they were frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until further analysis. Gonads obtained for immunohistochemistry were fixed in Bouin’s solution or 4% neutral-buffered formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin for histological analysis.

All embryos and fetuses included in the study appeared morphologically normal. Embryonic and fetal sex was first determined by gonadal morphology, and then confirmed by real-time PCR (39).

RNA extraction

Prior to RNA extraction, whole human embryonic/fetal male and female gonads were homogenized on a TissueLyser II at 4 °C (Qiagen) in 1.0 mL TRI reagent (cat. no. T9424, Sigma-Aldrich, Copenhagen, Denmark) for 2 × 30 seconds at 15 Hz, using 0.3 mm stainless steel beads. Samples were further homogenized by adding 200 µL chloroform, followed by 15 seconds shaking and incubation at room temperature for 2 to 3 minutes. The RNA was purified using silica membrane columns following the manufactured protocol (RNeasy Plus minikit, cat. no. 74136, Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Microarray analysis

Gene expression data from the present microarray analysis related to sex differentiation have previously been published describing the microarray methods in detail (36). Gonadal RNA samples were amplified using an Ovation Pico WTA v.2 RNA amplification system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nugen, San Carlos, CA) followed by cDNA synthesis using the Encore Biotin Module (Nugen, San Carlos, CA) before hybridization to the HTA 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Using the Robust Multichip Average (RMA) and prefiltering according to Bourgon and colleagues (40), the data were normalized as previously described (36). Log2 expression from 2.1 to 5 defined genes expressed in a compartment of cells and log2 expression above 5 defined genes being expressed in either all cells or abundantly in a subset of cells. The probes identifying the IGF2 gene also covered exons including in the INS gene and the expression detected represent both IGF2 and INS expression.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

RNA from embryonic and fetal gonads was converted to first-strand cDNA by the use of the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were kept on ice at all times. Real-time (RT-PCR) analysis was performed using TaqMan technology (Applied Biosystems), applying TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix from Invitrogen (Invitrogen, 2012 Life Technologies Corporation) and predesigned Taq-Man Gene Expression Assays for the following genes: IGF2, IGFBP4, IGFBP5, STC1, STC2, and PAPP-A (probe-id: IGF2, Hs04188276_m1, Hs04188276_m1; IGFBP4, Hs01057900_m1; IGFBP5, Hs00181213_m1; STC1, Hs00174970_m1; STC2, Hs01063215_m1; PAPPA, Hs01032307_m1) (Invitrogen). The genes were selected based on their regulative role of IGF bioactivity. The cDNA samples were amplified in duplicates using the LightCycler 480 quantitative PCR instrument (Roche). Human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as endogenous control (probe id. No.: 433764 F). All samples were normalized to GAPDH and the relative expression was quantified according to the Comparative CT Method (41).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5-μm paraffin-embedded sections, which were deparaffinized in xylene, gradually rehydrated in ethanol (99%, 96%, and 70%) followed by antigen retrieval in either 10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6 or in 10 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EGTA, pH 9. Endogenous activity was inhibited using 3% peroxidase, followed by inhibition of nonspecific binding with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma Aldrich, Copenhagen, Denmark). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C in a humid chamber; details of antibodies and conditions are given in Table 1. A secondary rabbit-anti-mouse-HRP conjugated antibody was used (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and visualised with 3.3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB+ Substrate Chromogen System, Dako). Both Universal negative control serum (BioCare Medical, CA) and antibody dilution buffer was used in place of primary antibody as IgG-negative controls and showed no staining in all specimens; data not shown.

Table 1.

Antibody information

| Antibody | Species | Supplier | Cat. No. | Concentration | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1R | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technologya | 3027S | 2.6 µg/mL | 1:50 |

| PAPP-A | Mouse | Giftb | - | 6.4 µg/mL | 1:100 |

| STC1 | Mouse | Giftb | - | 2.3 µg/mL | 1:300 |

| STC2 | Mouse | Giftb | - | 2.5 µg/mL | 1:400 |

| IGFBP4 | Mouse | Giftb | - | 10 µg/mL | 1:100 |

| IGFBP5 | Mouse | Giftb | - | 6.3 µg/mL | 1:300 |

| CYP17A1 | Mouse | Santa Cruzc | Sc-374244 | 2 µg/mL | 1:100 |

| LIN28 | Rabbit | Abcamd | Ab46020 | 10 µg/mL | 1:100 |

a BioNordika Denmark A/S, Herlev, Denmark

b Claus Oxvig, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics - Molecular Intervention, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

e Heidelberg, Germany

d Cambridge, UK

Immunofluorescence

To investigate the localization of PAPP-A and the Leydig cell marker CYP17A1, immunofluorescence was performed. Briefly, 5-μm paraffin tissue sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series. Antigens were retrieved with Tris-EGTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EGTA, pH 9) boiled in a pressure cooker for 20 minutes. After cooling, slides were blocked in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 1% BSA (TBS: 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) for 1 hour prior to incubating with primary antibody (Table 1) at 4 °C overnight. After incubation, slides were rinsed in TBS supplemented with Tween-20 (TBST) (100 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.6) and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After rinsing with TBST, slides were counterstained with DAPI (1:100) and mounted with Prolong Gold mounting medium (cat. No. P36930, Invitrogen).

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses of microarray and RT-PCR gene expression data were performed using a generalized linear model with a 2-way interaction between embryonic/fetal sex and age. Normality checks were performed prior to each transcript data analysis. The potential for maternal age effects on RT-PCR gene expression profiles was analyzed using the Pearson correlation model. For the purpose of this study, raw data were log2 transformed for consistency. Statistical significance was set to < 0.05 and confidence intervals at 95% were calculated and represented graphically. All statistical analyses and generation of graphs was performed using R Software version 3.6.0 and ggplot2.

Results

Screening for IGF signaling family members

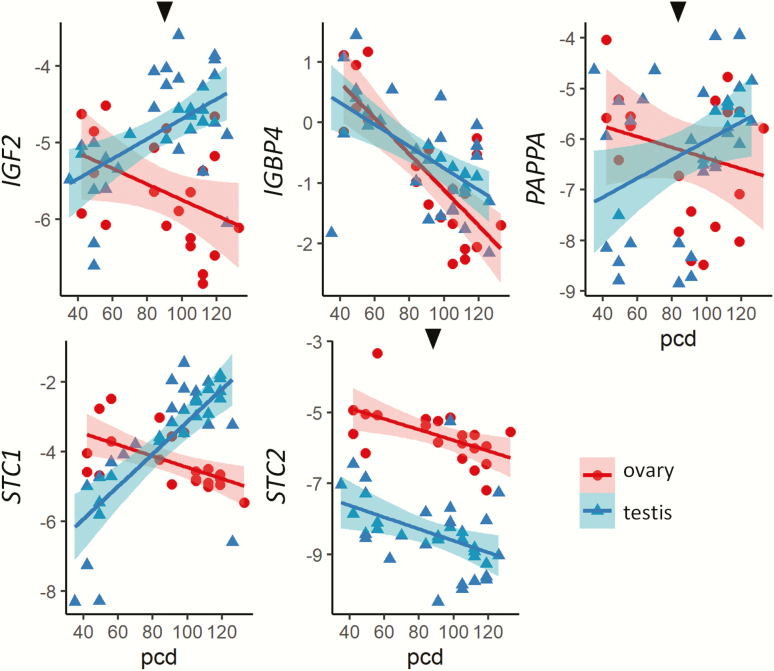

Gene expressions in both ovaries and testes in relation to age (postconception days, pcd) are shown in Fig. 2. One-way interactions of expression with age for each sex separately, and 2-way interactions with age together with sex, were checked for each presented gene. Expression of IGF1 mRNA increased with age in both sexes, although this was only statistically significant in testes (P = 0.013). No difference in expression was observed between the sexes. In contrast, the INS-IGF2 expression (combined expression of insulin and IGF2) increased significantly with age in testis (P < 0.001) and decreased in ovaries (P = 0.002). The IGF1R showed similar expression patterns, with a lower expression in ovaries than testes, a significant difference between the sexes was detected (P = 0.044). Both IGF1R and INSR increased significantly across gestation in testes (P < 0.001, P < 0.001), not in ovaries (P = 0.869, P = 0.865). All IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) 1-6 were expressed in the first-trimester gonads, with no significant difference in transcript levels between the sexes. The expression of IGFBP3 and IGFBP5 decreased significantly with age in both sexes (testes: P < 0.001, P = 0.003; ovaries: P = 0.003, P = 0.001) respectively, while no changes were observed according to age for other IGFBPs. PAPP-A and PAPPA-2 both significantly decreased with age in testes and ovaries (testes P < 0.001, P < 0.001; ovaries P = 0.007, P = 0.014), respectively. Overall, STC1 expression was higher than STC2 in both sexes. Only testicular STC1 expression increased significantly with age (P < 0.001) but was significantly lower (P = 0.014) than ovarian expression levels. There was no significant difference in the expression levels of STC2 between males and females. The downstream targets INSR, IRS1 and IRS2, were differentially expressed between the sexes. IRS1 was significantly higher (P = 0.011) in ovaries, while IRS2 was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in testes. Age differences were also seen, with IRS1 expression significantly decreasing across gestation in ovaries (P < 0.001) but not in testes, and IRS2 expression significantly increased with age in testes (P < 0.001) but not in ovaries. Moreover, a significantly higher IRS2 expression was seen in testes from 53 pcd and onwards compared to before day 53 (P = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Effects of fetal age and sex on IGF signaling pathway members. Data were from microarray analysis of 18 ovaries (42-64 pcd) and 28 testes (40-68 pcd). Black arrows above graphs indicate a 2-way significant interaction between sex, age, and expression levels. Shading illustrate 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviation: pcd, postconception days.

Confirmation of IGF component transcripts in first- and second-trimester gonads

A larger cohort of 34 male and 21 female gonads aged 5 to 17 pcw were used to perform RT-PCRs on IGF2, IGFBP4, PAPPA, STC1, and STC2 genes (Fig. 3). We observed no correlation between maternal age and any of the reported gene expression profiles (data not shown). As seen in the previous analysis, IGF2 expression increased in males and decreased in females across gestation, resulting in significant differential expression (P < 0.001) between the sexes. However, the rate of change in expression across gestation was significant only for males (P = 0.001). Expression of IGFBP4 decreased significantly across gestation in both sexes (P < 0.001). A sex dimorphic expression pattern was observed for PAPP-A (P = 0.030), with an increase in males and a decrease in females across gestation. In testes, PAPP-A expression increased significantly with age (P = 0.032), which was not the case in ovaries (P = 0.3). Transcript levels for STC1 increased in males and decreased in females with significant differences for sex (P < 0.001) and age in both males (P < 0.001) and females (P = 0.006), in agreement with the microarray. The STC2 expression was higher in ovaries than testes confirming the microarray analysis. A significant decrease in STC2 expression across gestation was observed in both testes (P = 0.01) and ovaries (P = 0.009).

Figure 3.

Confirmation of microarray findings for a larger population. Relative transcript levels from qPCR analysis of 21 ovaries (42-133 pcd) and 34 testes (35-126 pcd) are shown. Black arrows above graphs indicate a 2-way significant interaction between sex, age, and expression levels. Shading indicates 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviation: pcd, postconception days.

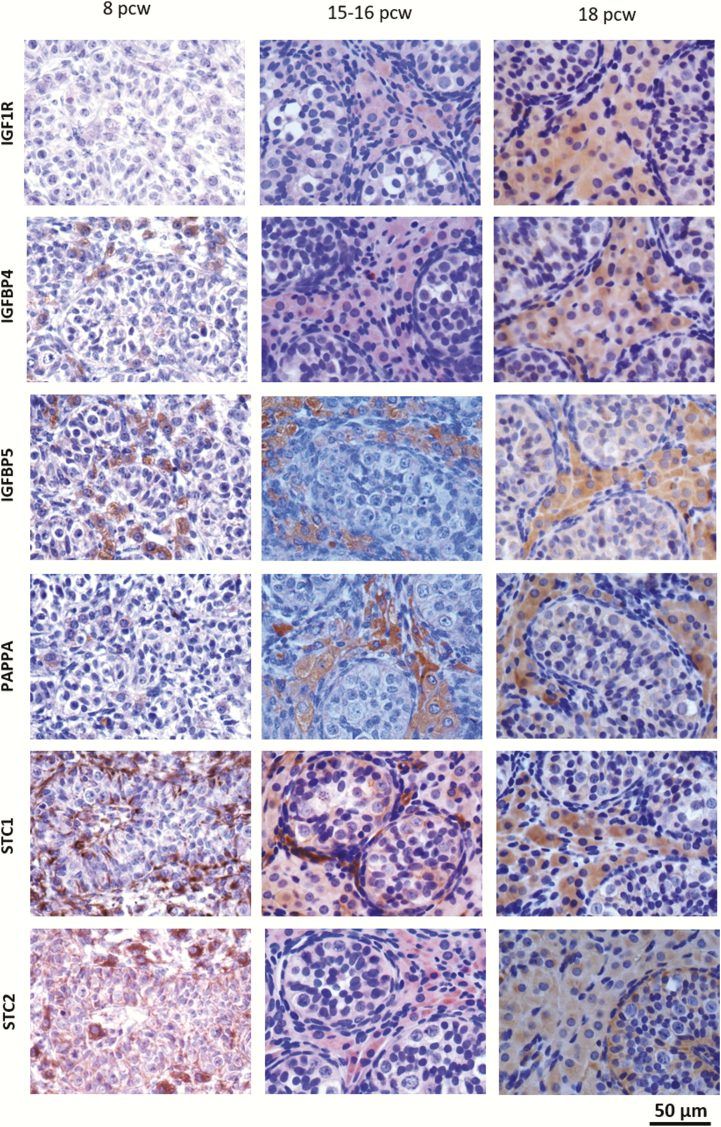

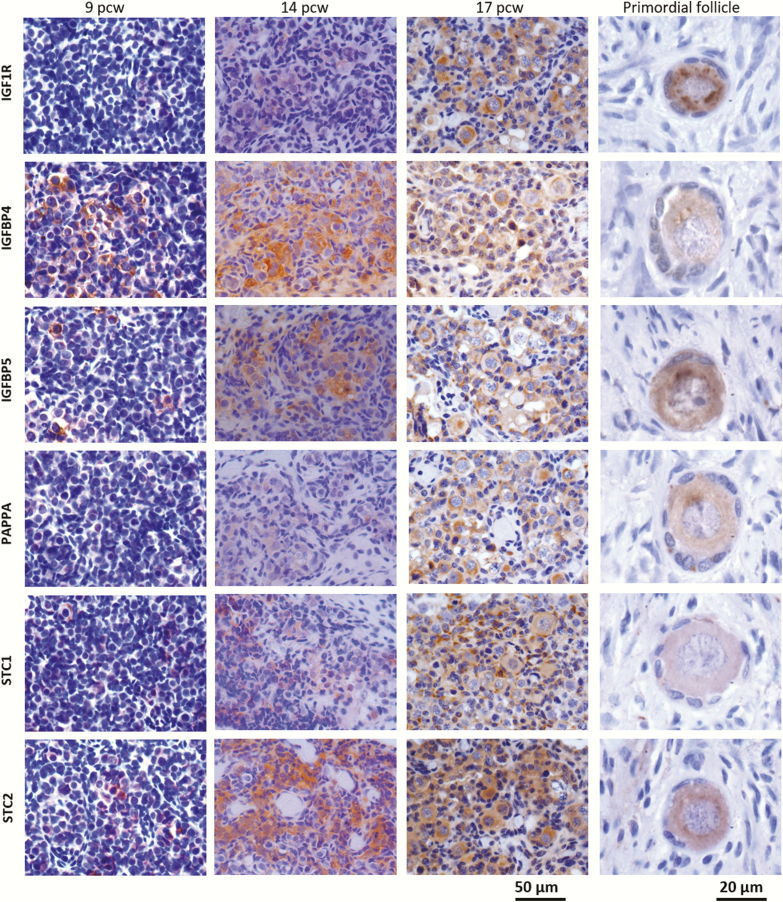

Immunohistochemical analysis

Using immunohistochemistry, expression at the protein level of key IGF regulators (IGF1R, PAPPA, STC1, STC2, IGFBP-4, and IGFBP-5) in both testes and ovaries from pcw 5 to 18 was then assessed. Representative images are shown in Fig. 4. The analyses were performed in ovaries from consecutive pcw 6 and 8 to 18, representing all developmental weeks, except week 7. Testes included all pcw 6 to 18. In testes, proteins of the IGF system localized primarily to Leydig cells although detection in germ and Sertoli cells was also observed (Fig. 4A). In contrast, proteins of the IGF system were generally expressed in both germ cells and somatic cells in the ovary, with no preference to a specific cell type (Fig. 4B). A tendency to more intense staining in the germ cells was observed.

Figure 4.

Localization of IGF1R, IGFBP4, IGFBP5, PAPP-A, STC1, and STC2 in embryonic and fetal testes (A) and ovaries (B).The components were located primarily in the Leydig cells in testes, with a weak detection in germ and Sertoli cells, whereas a general expression was seen in the ovary, with a prevalence to germ cells. Scale bars: fetal gonads = 50 µm, primordial follicle = 20 µm.

PAPP-A in second-trimester testis and ovary

PAPP-A was detected in Leydig cells of a human male 17 pcw testis. Double staining with the Leydig cell marker CYP17 confirmed that PAPP-A was primarily located outside the seminiferous tubules with expression distinctly located to Leydig cells (Fig. 5A). In the 18 pcw human fetal ovary, PAPP-A showed less specific localization. Double staining with the germ cell marker LIN28 revealed localization of PAPP-A in some germ cells along with other cell types (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Fluorescent staining of A) PAPP-A together with the Leydig cell marker CYP17 in 17 pcw testis. White arrows indicate Leydig cell staining. PAPP-A was localized in Leydig cells and there was no protein presence within the seminiferous tubules. B) PAPP-A and the germ cell marker LIN28 in an 18 pcw fetal ovary. White arrows indicate a cluster of germ cells. There was a more global localization of PAPP-A in the ovary. PAPP-A was present in some germ cells; however, it was also seen in other cell types. Abbreviation: ST, seminiferous tubule.

Discussion

This study describes, for the first time, expression of IGF system regulators in human ovaries and testes during embryonic and fetal life, at both gene and protein levels. These results demonstrate that IGF is potentially involved in gonadal growth and development as early as the embryonic stages around sex differentiation (6 pcw) and onset of male steroidogenesis (8 pcw) (36, 42). Moreover, the IGF signaling components increasing in expression with embryonic/fetal age (ie, INS-IGF2, IGF1R, INSR, IRS2), were generally upregulated in testes compared to ovaries. In first-trimester gonads, PAPP-A decreased with age in both sexes. Surprisingly, the expression in testes increased when specimens from both first- and second-trimester were included, indicating a biphasic PAPP-A expression pattern, with downregulation in the first trimester, while there is an upregulation in the second trimester. Consequently, it may be hypothesized that bioavailable IGF2 is reduced in the first trimester, with a relative increase in the second trimester. Methodologically, the array probe detecting IGF2 also included INS, whereas the qPCR probe detected IGF2 alone. Since the expression patterns obtained by the 2 different methods were in agreement, the contribution of INS to the array expression is probably minor. The IGF binding proteins remained constant between sexes across gestation in both sexes, while STC1 and STC2 were upregulated in ovaries compared with testes in first-trimester specimens. Interestingly, the STC1 expression increased significantly in second-trimester testes, where the expression was higher than ovaries, illustrating a significantly increased STC1 expression in testes across gestation. Collectively, this suggests that the IGF system is a more central regulator in testes than in ovaries during embryonic and fetal development. This is interesting, since there is hardly any circulation in embryos at these early developmental stages, suggesting that IGF signaling occurs via para- and autocrine mechanisms in the developing gonads. Similarly, IGF signaling in the avascular human ovarian follicles has been described (28, 43), emphasizing that active IGF signaling is not dependent on direct contact to the circulation. IGF1 was upregulated in both sexes across gestation, whereas IGF2 was upregulated in testes and downregulated in ovaries, indicating a more profound role for IGF2 in testes than in ovaries.

Overall, there was good agreement between the 2 methods used for evaluating gonadal transcript expression of IGF signaling (ie, microarray and qPCR analysis). The present study is retrospective and the functional roles of the IGF system are not directly elucidated by these analyses. Further studies are needed to evaluate the precise regulatory effects that IGF signaling may exert on early fetal gonadal development as well as possible regulatory effects on the testicular steroidogenesis.

Our findings confirm and extend the observations by Voutilainen and Miller, who, more than 3 decades ago, reported IGF2 to be expressed in human fetal gonads (13-26 gestational weeks) with a higher expression in testes than ovaries (26). While Voutilainen and Miller found a decrease in IGF2 expression in testis from gestational week 13 to 26, we here show a significant increase from pcw 5 to 16, indicating that IGF2 may be a particularly important regulator during the crucial early events of sex differentiation and onset of steroidogenesis in males, which takes place in pcw 6 and 8, respectively (36, 42). Taken together, this suggests that IGF signaling is relatively upregulated in the embryonic and fetal testes as compared to the ovary, indicating that IGF signaling may play a more important regulatory role in the developing testes than in the ovary. In adults, the regulation of IGF signaling components changes with age (44, 45) and we tested whether maternal age was associated with the level of embryonic and fetal IGF gene expression; however, our data did not show any such associations.

Our gene expression analyses revealed that both STC1 and STC2 as well as PAPP-A were expressed in testes and ovaries, indicating that proteinase-inhibitor complex formation is possible, and that PAPP-A activity may be regulated by both STC1 and STC2. It has previously been shown in mice in vitro that STC1 and STC2 inhibit the proteolytic activity of PAPP-A (11, 12). Moreover, PAPP-A, STC1, STC2 and the inhibited complexes have been detected in human follicular fluids, demonstrating that complex formation occurs in adult human ovarian tissues, and suggesting that STC1 and STC2 regulate PAPP-A in the adult human ovary during folliculogenesis (43). The present study detected a significant upregulation of STC1 transcript in testes across gestation, suggesting that PAPP-A may primarily be regulated by STC1 during the first and second trimesters.

Gene expression of the intracellular IGF signaling mediators, IRS-1 and IRS-2, were detected in gonads of both sexes. Interestingly, IRS-1 expression was decreasing across gestation in ovaries and constantly expressed in testes, while IRS-2 was increasing across gestation in testis and constantly expressed in ovaries. This indicates a sex dimorphic intracellular IGF signal transduction, with transduction increasing in testes and decreasing in ovaries with age. This illustrates that IGF regulation may be more critical in embryonic and fetal testis than in ovaries. IRS-2 increased significantly in testes from day 53 and onwards, compared to the levels before day 53, which correlates exactly with the previously reported onset of human steroidogenic onset around postconception day 53 (36). This supports the hypothesis that IGF-mediated signaling may affect steroidogenesis in human fetal Leydig cells, as seen in human postnatal Leydig cells (23). In the adult human testis, both IRS-1 and IRS-2 have been detected. Furthermore, IRS-1 has been detected in peritubular myoid cells and interstitial cells, which is in accordance with the high energy expenditure of these contractile cells in the adult testis (46). Irs-2 is required for normal testis development in mice. Contradictorily, Irs-2 deficient mice present with abnormalities in Sertoli cells and germ cells rather than in Leydig cells (19), indicating that IGF regulation is likely to be different between the two species. However, Irs-2 has been detected in Sertoli cells, germ cells, and Leydig cells in adult rat testes, suggesting that IGF signaling may be functional in additional testicular cell type at different developmental phases.

Our immunohistochemical analysis showed that all evaluated components of the IGF system were present at the protein level in both testes and ovaries. Furthermore, in testes, the IGF components located primarily to Leydig cells, which implies that IGF signaling may exert functions in different cell compartments at various time points, as well as playing a sex-specific role in regulating fetal Leydig cells differentiation and steroidogenesis. PAPP-A and CYP17A1 (a key enzyme in androgen synthesis) were also located specifically to embryonic/fetal human Leydig cells, further supporting the hypothesis that IGF signaling may affect early steroidogenesis. These observations confirm a previous report, which also detected IGF-2, IGF1R, and INSR primarily located in Leydig cells in postnatal human testes and implied that IGF signaling was involved in postnatal human testicular differentiation and steroidogenesis (23). The present study found that both IGF-1 and IGF-2 are expressed in embryonic and fetal testis. Previous studies have reported that serum IGF-1 levels correlate with size of testes in children and adolescents (35) and that adult human Leydig cells, Sertoli cells, and spermatocytes express IGF-1 (33). One study found IGF-2 expressed in spermatocytes and in some Sertoli cells in adult testicular tissue (47). Furthermore, IGF-2 correlated with the FSH receptor (FSHR) expression, implicating a paracrine control of spermatogenesis (47). A potential different regulation and function of IGFs in fetal gonads than in adults require further studies to elucidate.

In summary, our data provide the first evidence that the IGF signaling system is active in human embryonic and fetal gonads of both sexes, with a relatively higher expression of most components in testes compared to ovaries. The IGF components were located primarily to Leydig cells in testis, suggesting a regulatory role in differentiation and steroidogenesis.

Limitations

First- and second-trimester specimens were collected in Denmark and Scotland, respectively, and geographical differences in maternal lifestyles which potentially could affect results cannot be excluded. There were no obvious differences between the Danish and Scottish participants regarding age, BMI, and rural/urban site of living. All analyses were performed in Denmark in order to maintain methodological consistency. Moreover, the data are descriptive and further studies are required for mechanistic conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Marianne Sguazzino is acknowledged for excellent technical assistance. Gabriela Gudbergsen is acknowledged for her excellent design of Figure 1.

Financial Support: This work was supported by The Medical Research Council [MR/L010011/1 to PAF] and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) [under grant agreement no 212885 to PAF], BBSRC/EASTBIO (to AZ), ESHRE supported the ReproUnion fellowship (to AZ), Rigshospitalets Forskningspuljer (to LSM), and ReproUnion 1.0 (to LSM).

Author Contributions: L.S.M. designed the project, obtained embryonic and fetal specimens from the Danish cohort, was responsible for the microarray analysis, did immunohistochemistry and wrote the paper. Z.A. collected the fetal specimens from the UK, did immunohistochemical staining, statistical analysis, performed qPCR analysis, and wrote the paper. J.A.B. did the qPCR analysis and wrote the paper. J.H. did immunohistochemical staining. E.E. recruited Danish patients and evacuated embryos and fetuses. C.O. developed IGF-related antibodies and participated in writing the paper. P.A.F. was responsible for the UK fetal cohort and designed the project. C.Y.A. designed the project and participated in writing the paper. Authors L.S.M., Z.A., C.O., P.A.F., and C.Y.A. were responsible for final editing and approval of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IGF

insulin-like growth factor

- IGFBP

insulin-like growth factor binding proteins

- IGFR1

insulin-like growth factor receptor type 1

- INSR

insulin receptor

- IRS

insulin receptor substrate

- PAPP-A

pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A

- pcd

postconception days

- pcw

postconception weeks

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: The dataset generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Microarray data are available with the Array Express accession number: E-MTAB-5611.

References

- 1. Annunziata M, Granata R, Ghigo E. The IGF system. Acta Diabetol. 2011;48(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell. 1993;75(1):73-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeChiara TM, Efstratiadis A, Robertson EJ. A growth-deficiency phenotype in heterozygous mice carrying an insulin-like growth factor II gene disrupted by targeting. Nature. 1990;345(6270):78-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Le Roith D. The insulin-like growth factor system. Exp Diabesity Res. 2003;4(4):205-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, et al. . Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(5):3278-3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohan S, Baylink DJ, Pettis JL. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding proteins in serum–do they have additional roles besides modulating the endocrine IGF actions? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(11):3817-3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Firth SM, Baxter RC. Cellular actions of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(6):824-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boldt HB, Conover CA. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A): a local regulator of IGF bioavailability through cleavage of IGFBPs. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2007;17(1):10-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oxvig C. The role of PAPP-A in the IGF system: location, location, location. J Cell Commun Signal. 2015;9(2):177-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laursen LS, Overgaard MT, Weyer K, et al. . Cell surface targeting of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A proteolytic activity. Reversible adhesion is mediated by two neighboring short consensus repeats. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(49):47225-47234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jepsen MR, Kløverpris S, Mikkelsen JH, et al. . Stanniocalcin-2 inhibits mammalian growth by proteolytic inhibition of the insulin-like growth factor axis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(6):3430-3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kløverpris S, Mikkelsen JH, Pedersen JH, et al. . Stanniocalcin-1 potently inhibits the proteolytic activity of the metalloproteinase pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(36):21915-21924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker J, Hardy MP, Zhou J, et al. . Effects of an Igf1 gene null mutation on mouse reproduction. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10(7):903-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pitetti JL, Calvel P, Romero Y, et al. . Insulin and IGF1 receptors are essential for XX and XY gonadal differentiation and adrenal development in mice. Plos Genet. 2013;9(1):e1003160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nef S, Verma-Kurvari S, Merenmies J, et al. . Testis determination requires insulin receptor family function in mice. Nature. 2003;426(6964):291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pitetti JL, Calvel P, Zimmermann C, et al. . An essential role for insulin and IGF1 receptors in regulating sertoli cell proliferation, testis size, and FSH action in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27(5):814-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Froment P, Vigier M, Nègre D, et al. . Inactivation of the IGF-I receptor gene in primary Sertoli cells highlights the autocrine effects of IGF-I. J Endocrinol. 2007;194(3):557-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cannarella R, Condorelli RA, La Vignera S, Calogero AE. Effects of the insulin-like growth factor system on testicular differentiation and function: a review of the literature. Andrology. 2018;6(1):3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Griffeth RJ, Carretero J, Burks DJ. Insulin receptor substrate 2 is required for testicular development. Plos One. 2013;8(5):e62103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Villalpando I, López-Olmos V. Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) regulates endocrine activity of the embryonic testis in the mouse. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86(2):151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Villalpando I, Lira E, Medina G, Garcia-Garcia E, Echeverria O. Insulin-like growth factor 1 is expressed in mouse developing testis and regulates somatic cell proliferation. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233(4):419-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yao J, Zuo H, Gao J, Wang M, Wang D, Li X. The effects of IGF-1 on mouse spermatogenesis using an organ culture method. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491(3):840-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Berensztein EB, Baquedano MS, Pepe CM, et al. . Role of IGFs and insulin in the human testis during postnatal activation: differentiation of steroidogenic cells. Pediatr Res. 2008;63(6):662-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Özdamar MY, Şahin S, Zengin K, Seçkin S, Gürdal M. Detection of insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 in the human cremaster muscle and its role in the etiology of the undescended testis. Asian J Surg. 2019;42(1):290-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koskenniemi JJ, Virtanen HE, Wohlfahrt-Veje C, et al. . Postnatal changes in testicular position are associated with IGF-I and function of sertoli and leydig cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(4):1429-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Voutilainen R, Miller WL. Developmental and hormonal regulation of mRNAs for insulin-like growth factor II and steroidogenic enzymes in human fetal adrenals and gonads. DNA. 1988;7(1):9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poljicanin A, Filipovic N, Vukusic Pusic T, et al. . Expression pattern of RAGE and IGF-1 in the human fetal ovary and ovarian serous carcinoma. Acta Histochem. 2015;117(4-5):468-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bøtkjær JA, Jeppesen JV, Wissing ML, et al. . Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A in human ovarian follicles and its association with intrafollicular hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(5):1294-301.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou P, Baumgarten SC, Wu Y, et al. . IGF-I signaling is essential for FSH stimulation of AKT and steroidogenic genes in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27(3):511-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thierry van Dessel HJ, Chandrasekher Y, Yap OW, et al. . Serum and follicular fluid levels of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), IGF-II, and IGF-binding protein-1 and -3 during the normal menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(3):1224-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chandrasekher YA, Van Dessel HJ, Fauser BC, Giudice LC. Estrogen- but not androgen-dominant human ovarian follicular fluid contains an insulin-like growth factor binding protein-4 protease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(9):2734-2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Geisthovel F, Moretti-Rojas I, Asch RH, Rojas FJ. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), but not IGF-I mRNA, in human preovulatory granulosa cells. Hum Reprod. 1989;4(8):899-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vannelli BG, Barni T, Orlando C, Natali A, Serio M, Balboni GC. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and IGF-I receptor in human testis: an immunohistochemical study. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(4):666-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lejeune H, Sanchez P, Saez JM. Enhancement of long-term testosterone secretion and steroidogenic enzyme expression in human Leydig cells by co-culture with human Sertoli cell-enriched preparations. Int J Androl. 1998;21(3):129-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Juul A, Bang P, Hertel NT, et al. . Serum insulin-like growth factor-I in 1030 healthy children, adolescents, and adults: relation to age, sex, stage of puberty, testicular size, and body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(3):744-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mamsen LS, Ernst EH, Borup R, et al. . Temporal expression pattern of genes during the period of sex differentiation in human embryonic gonads. Nat Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walker N, Filis P, O’Shaughnessy PJ, Bellingham M, Fowler PA. Nutrient transporter expression in both the placenta and fetal liver are affected by maternal smoking. Placenta. 2019;78:10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O’Shaughnessy PJ, Baker PJ, Monteiro A, Cassie S, Bhattacharya S, Fowler PA. Developmental changes in human fetal testicular cell numbers and messenger ribonucleic acid levels during the second trimester. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(12):4792-4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakahori Y, Hamano K, Iwaya M, Nakagome Y. Sex identification by polymerase chain reaction using X-Y homologous primer. Am J Med Genet. 1991;39(4):472-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bourgon R, Gentleman R, Huber W. Independent filtering increases detection power for high-throughput experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(21):9546-9551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Byskov AG. Differentiation of mammalian embryonic gonad. Physiol Rev. 1986;66(1):71-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jepsen MR, Kløverpris S, Bøtkjær JA, Wissing ML, Andersen CY, Oxvig C. The proteolytic activity of pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A is potentially regulated by stanniocalcin-1 and -2 during human ovarian follicle development. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(4):866-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mohan S, Farley JR, Baylink DJ. Age-related changes in IGFBP-4 and IGFBP-5 levels in human serum and bone: implications for bone loss with aging. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1995;6(2-4):465-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O’Connor KG, Tobin JD, Harman SM, et al. . Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-I are related to age and not to body composition in healthy women and men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53(3):M176-M182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kokk K, Veräjänkorva E, Laato M, Wu XK, Tapfer H, Pöllänen P. Expression of insulin receptor substrates 1-3, glucose transporters GLUT-1-4, signal regulatory protein 1alpha, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase B at the protein level in the human testis. Anat Sci Int. 2005;80(2):91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Neuvians TP, Gashaw I, Hasenfus A, Hacherhäcker A, Winterhager E, Grobholz R. Differential expression of IGF components and insulin receptor isoforms in human seminoma versus normal testicular tissue. Neoplasia. 2005;7(5): 446-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]