Abstract

A previously unrecognized penicillin binding protein (PBP) gene, pbpF, was identified in Staphylococcus aureus. This gene encodes a protein of 691 amino acid residues with an estimated molecular mass of 78 kDa. The molecular mass is very close to that of S. aureus PBP2 (81 kDa), and the protein is tentatively named PBP2B. PBP2B has three motifs, SSVK, SSN, and KTG, that can be found in PBPs and β-lactamases. Recombinant PBP2B (rPBP2B), which lacks a putative signal peptide at the N terminus and has a histidine tag at the C terminus, was expressed in Escherichia coli. The purified rPBP2B was shown to have penicillin binding activity. A protein band was detected from S. aureus membrane fraction by immunoblotting with anti-rPBP2B serum. Also, penicillin binding activity of the protein immunoprecipitated with anti-rPBP2B serum was detected. These results suggest the presence of PBP2B in S. aureus cell membrane that covalently binds penicillin. The internal region of pbpF and PBP2B protein were found in all 12 S. aureus strains tested by PCR and immunoblotting.

Penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), which are membrane-bound enzymes, catalyze carboxypeptidase or transpeptidase reactions for bacterial peptidoglycan synthesis. In methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), four PBPs (PBP1, 85 kDa; PBP2, 81 kDa; PBP3, 75 kDa; and PBP4, 45 kDa) have been identified (9), and an extra PBP [PBP2′ (A)] is also found in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (2, 26). S. aureus PBP1 to -4 are targets of β-lactam antibiotics. β-lactam antibiotics bind to these PBPs due to structural similarity, and cell wall synthesis is inhibited. In MRSA, PBP2′ (A) has low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics, so this PBP can still function in the presence of a concentration of β-lactam antibiotics that inhibits other PBPs (8, 19).

In addition to PBP2′ (A), the expression levels and modifications of other PBPs have also been associated with methicillin resistance in S. aureus (4). Overexpression of PBP4 enhanced resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (4, 11). Modified PBP1, PBP2, and PBP4 were also associated with increased methicillin resistance due to the decrease in penicillin affinity, although their precise mechanism remains unknown (25).

The DNA sequences encoding PBP1, -2, -2′, and -4 have been determined (11, 17, 26, 27). Also, several experiments have demonstrated that PBP1, or PBP1 in combination with PBP2 or PBP3, is essential for cell viability (3), while PBP4 is nonessential (6, 11).

Here, we report a previously unrecognized PBP2B gene that was identified from S. aureus sequence data. Also, we demonstrate that the protein has penicillin binding activity and is expressed in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and S. aureus were grown in Luria-Bertani broth and Trypticase soy broth (TSB) (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.), respectively. When necessary, ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was added.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Origin or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | ||

| ISP3 | Laboratory strain; Mcs | J. Iandolo (P. A. Pattee’s collection) |

| COL | Laboratory strain; Mcr | A. Tomasz, 15 |

| RN450 | Laboratory strain; Mcs; NCTC8325-4 (NCTC8325 UV cured) | R. Novick |

| E. coli | ||

| XL-1 Blue | rec-1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac | 21 |

| M15 (pREP4) | [F′ proAB lacIqZM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Qiagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| PCR2.1 | PCR cloning vector; Ampr in E. coli | Invitrogen |

| pGEM T-Easy | PCR cloning vector; Ampr in E. coli | Promega |

| pQE70 | Expression vector | Qiagen |

| pHK4247 | 4.4-kb PCR fragment containing pbpF (ISP3)/PCR2.1 | This study |

| pHK4315 | 2.4-kb PCR fragment containing pbpF (RN450)/pGEM T-Easy | This study |

DNA sequence of the gene encoding a possible PBP.

S. aureus chromosomal DNA was prepared from an overnight culture of the ISP3 strain in TSB with the Puregene Gram+ DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The genome of S. aureus ISP3 was sequenced by the whole-genome random-sequencing method as previously described for the sequencing of other microbial genomes (7) at Human Genome Sciences, Inc. (Rockville, Md.). From this collection of S. aureus genomic DNA sequences, a putative penicillin binding protein homolog was identified based upon sequence homology to the PBP2B of Streptococcus pneumoniae.

DNA manipulations.

Routine DNA manipulations; DNA digestion with restriction enzymes and shrimp alkaline phosphatase; DNA ligations, gel electrophoresis, and hybridization; and DNA sequencing were performed essentially as described previously (21). Restriction enzymes and shrimp alkaline phosphatase were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica, Tokyo, Japan, and T4 DNA ligase was purchased from New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass. PCR reagents were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim, and PCR was performed with the GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin-Elmer).

Construction of recombinant protein of PBP2 and PBP2B.

An expression construct was made by removing the hydrophobic leader peptide region to facilitate expression and purification of the recombinant protein. The open reading frame (ORF) encoding the putative PBP2B starting at amino acid 44 (Q) was PCR amplified with the following oligonucleotide primers (3948 Nucleic Acid Synthesis and Purification System; Applied Biosystems): N-terminal primer, 5′-CAGTGCATGCCACAAATCGCACAAGGCTCA-3′, and C-terminal primer, 5′-GACTGGATCCTTTGTCTTTGTCTTTATTTTTATC-3′. The PCR product was digested with SphI and BamHI (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) and ligated into the protein expression vector pQE70 (Qiagen), and then E. coli M15 (pREP4) cells were transformed. A clone with the correct PBP2B ORF sequence was selected to prepare six-His-tagged recombinant protein from the M15 (pREP4) cells following Qiagen’s protocol. Native protein was eluted from Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin by raising the concentration of imidazole from 40 to 500 mM. To make recombinant PBP2, the DNA fragment amplified with two primers (N-terminal primer, 5′-ACTGGCATGCCTGCTTTTACCGAAGCTAAATTACAAG-3′, and C-terminal primer, 5′-AGTCGGATCCGTTGAATATACCTGTTAATCCACCGCTG-3′) was cloned into pQE70 and then transformed into M15 (pREP4). The protein was purified as described above.

Antisera.

One hundred micrograms of the purified protein (PBP2B) emulsified with an equal volume of Freund’s complete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was administered by hypodermic injection to a rabbit (weight, 2 kg). After 2, 4, and 6 weeks, the rabbit was injected with 100 μg of the purified protein emulsified with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories) and then injected intravenously with 50 μg of the purified protein. Three days after the final injection, antiserum was obtained. Anti-PBP2 (obtained from rats) was kindly provided by K. Murakami, Shionogi Research Laboratories, Osaka, Japan (17).

Penicillin binding assay.

Cell membrane fractions from S. aureus or E. coli were obtained by differential centrifugation as described elsewhere (14). For the E. coli system, we assayed penicillin binding activity with two membrane fractions of E. coli XL-1 Blue containing pbpF of ISP3 or RN450. pbpF, amplified from RN450 chromosomal DNA, was cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Tokyo, Japan) and then transformed to E. coli XL-1 Blue. Twenty micrograms of membrane protein was labeled for 15 min at 37°C with 3H-benzylpenicillin (250 μg/ml; 10 to 30 Ci/mmol; Amersham International, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The purified recombinant protein (0.15 μg [2 pmol]) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was incubated with various concentrations of 3H-benzylpenicillin (twofold dilution from 10 to 0.15 ng [27 to 0.4 pmol]). Each mixture was incubated at 37°C for 15 min, and then the reaction was stopped by addition of an equal volume of sample buffer (0.05 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 1.6% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.04% bromophenol blue, and 27% glycerol). After samples were boiled for 10 min, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), using 10% acrylamide gels, was performed. The protein bands reacted with 3H-benzylpenicillin were detected by fluorography. The reacted bands were then quantitated with an image scanner connected to the computer. The degree of saturation in each sample was calculated from the ratio of its density with that of the band reacted with 10 ng of 3H-benzylpenicillin. For the competition assay, various concentrations of penicillin G or methicillin (0.005, 0.01, and 0.1 μg/ml) were added before the addition of 3H-benzylpenicillin, and the mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Then, 5 ng (14 pmol) of 3H-benzylpenicillin was added and the mixture was further incubated for 15 min. Finally, the radioactive band was detected by fluorography.

Immunoprecipitation.

For immunoprecipitation experiments, we used methicillin-susceptible (RN450) and methicillin-resistant (COL) strains. A 1:100 dilution of an overnight culture of the S. aureus strain was inoculated into fresh TSB and grown with shaking until the optical density at 660 nm reached 0.8. After the cells were harvested and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 6.8), they were resuspended with PBS containing lysostaphin (100 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and then the supernatant was further ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min. Finally, the pellet was dissolved with 1% SDS in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and used as the membrane protein fraction. The protein concentration of the fraction was 5 mg/ml. Twenty microliters (100 μg) of membrane protein was diluted 10-fold with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Anti-PBP2B serum or normal serum was added to 100 μl of membrane protein (0.1% SDS) and incubated at room temperature for 60 min. Then, 50 μl of Protein A-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) was added and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min with gentle shaking. The protein A-Sepharose was washed with PBS five times. Sample buffer (50 μl) was added, and the mixture was boiled for 5 min. SDS-PAGE (7.5% polyacrylamide gel) was performed, and the separated proteins were transferred to nylon membrane (Hybond N; Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Immunoblotting was performed with anti-PBP2B or anti-PBP2 serum as the first antibody. Anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for anti-PBP2B or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for anti-PBP2 was used as the second antibody. Immunodetection was performed with Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) according to the manual supplied.

For the radiolabeling assay, membrane protein fraction suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was reacted with 3H-benzylpenicillin at 37°C for 20 min. Two microliters of 10% SDS was added to 20 μl of the mixture, and then 180 μl of PBS was added (final concentration, 0.1% SDS). Immunoprecipitation with anti-PBP2B serum or normal serum was performed as described above. After SDS-PAGE, radiolabeled protein bands were detected by fluorography.

Localization of PBP2B.

The fractionation of cells was performed as described elsewhere (24). Briefly, mid-log-phase cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g, and the cells were washed twice with PBS. The culture supernatant was concentrated 60 times by 80% saturated ammonium sulfate precipitation and used as the culture supernatant fraction. The cells were suspended in digestion buffer (30% raffinose and 0.145 M NaCl in 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) containing 100 μg of lysostaphin/ml, 100 μg of DNase/ml, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Protoplasts were obtained by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was used as the cell wall fraction. The protoplasts were disrupted by adding 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and then ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant was used as the cytoplasmic fraction, and the pellet, suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), was used as the membrane fraction. Western blotting of these fractions was performed with anti-PBP2B as the first antibody.

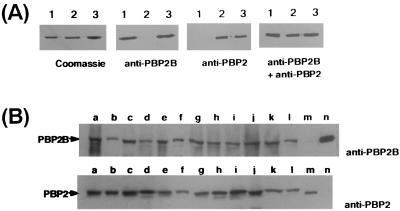

Immunoanalysis of PBP2 and PBP2B comigration.

To demonstrate the comigration of PBP2 and PBP2B, we performed immunoblotting with recombinant PBP2 (rPBP2) and PBP2B (rPBP2B). Four sets of three samples (PBP2, PBP2B, and PBP2 plus PBP2B) were loaded on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel. After SDS-PAGE, one set of gels was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The other gels were transferred to nylon membrane. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-PBP2, anti-PBP2B, or anti-PBP2 plus anti-PBP2B as the primary antibody.

We also performed immunoblotting of membrane protein fractions prepared from 12 S. aureus strains with anti-PBP2 or anti-PBP2B as the primary antibody.

PCR amplification of the PBP2B gene in different strains.

To determine whether pbpF is prevalent among various strains, PCR-based amplification of the internal DNA region of the PBP2B gene was performed with eight MRSA and four MSSA strains. Chromosomal DNAs were prepared from each strain as described previously. The primer set was PBP2B-1, 5′-CGA AAA TCG GAA AAT CAC-3′; and PBP2B-2, 5′-ACC ACC TTG GAA ATG TAA-3′.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence discussed in this work will appear in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession no. AF098801.

RESULTS

Sequence.

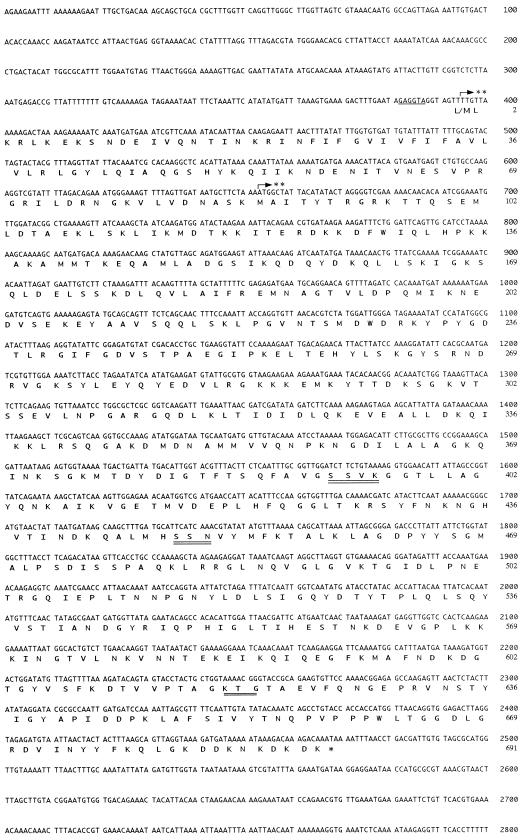

Figure 1 shows a restriction map of the gene, designated pbpF, encoding a putative penicillin binding protein. This gene, extending from nucleotides (nt) 395 to 2467, could potentially encode a protein of 691 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of 77.2 kDa. The computer analysis of the ORF for a putative penicillin binding protein suggested two initiation codons of pbpF, ATG (653 nt) and TTG (395 nt) (Fig. 2). Although the starting amino acid needs to be N-formylmethionine, we could not find the putative promoter and Shine-Dalgarno sequences upstream of the ATG codon but found them upstream of the TTG codon. Therefore, it is possible that the initial methionine is encoded by TTG. The signal sequence was found in the putative protein (1 to 43 amino acid residues).

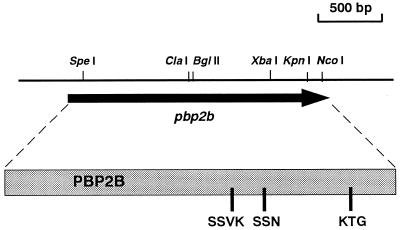

FIG. 1.

Mapping of the pbpF region of S. aureus ISP3. The arrow represents the ORF and its direction. The box represents the PBP2B protein with three motifs indicated.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of pbpF region from S. aureus ISP3. The ribosome binding site (Shine-Dalgarno sequence) is underlined, and three motifs are double underlined. The stop codon is marked by an asterisk. Two putative starting sites are marked by double asterisks.

The deduced protein exhibited a high degree of amino acid sequence similarity to an 80-kDa hypothetical protein (a PBP homolog) in Bacillus subtilis (42% identity), YkuA protein (another PBP homolog) in B. subtilis (36%), and PBP2B of S. pneumoniae (30%), Streptococcus oralis (26%), and Streptococcus thermophilus (31%). The deduced protein, PBP2B, has three conserved motifs (SXXK, K[H]T[S]G, and SXN) which are typically found in PBPs and β-lactamases. Two SXXK (49SHYK52 and 392SSVK395), four KTG (297KSG299, 372KSG374, 494KTG496, and 618KTG620), and three SXN (266SRN268, 448SSN450, and 558STN560) motifs were found in this protein. Considering the importance of the order and the distances between motifs, we speculated that 392SSVK395, 448SSN450, and 618KTG620 are key motifs for PBP activity.

Penicillin binding activity of rPBP2B.

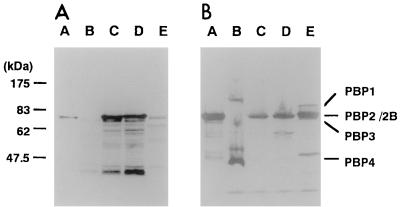

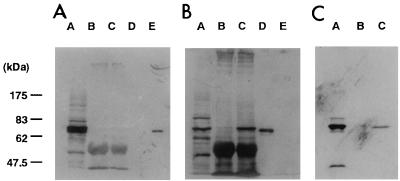

When PBP2B was expressed in E. coli XL-1, we found that the 70-kDa protein band reacted with anti-PBP2B in the whole-cell lysate (Fig. 3A, lanes C and D). These bands, as well as six-His-tagged rPBP2B, showed binding of 3H-benzylpenicillin (Fig. 3B, lanes A, C, and D). The bands were not present in cell lysates of E. coli XL-1 Blue without the plasmid pHK4247 (Fig. 3B, lane B). These results indicate that PBP2B expressed in E. coli possesses 3H-benzylpenicillin binding activity. When membrane proteins of S. aureus were used for the binding assay, we were not able to separate the two PBPs, PBP2 and PBP2B (Fig. 3B, lane E).

FIG. 3.

Immunoblotting (A) and fluorographic (B) analysis of E. coli and S. aureus membranes. The membrane fraction was prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-rPBP2B serum, and fluorography was performed with 3H-benzylpenicillin. Lanes: A, recombinant PBP2B; B, E. coli XL-1 Blue; C, E. coli XL-1 Blue/pHK4247; D, E. coli XL-1 Blue/pHK4315; E, S. aureus RN450. Standard molecular mass markers are indicated on the left. The positions of the PBPs are indicated on the right.

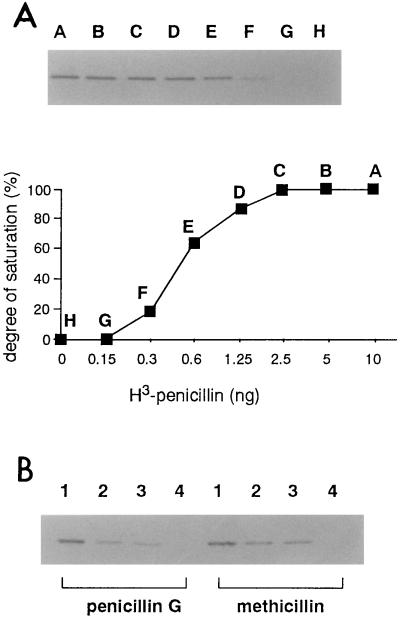

Figure 4 shows the kinetics of the penicillin binding activity of rPBP2B. Two pmol (0.15 μg) of rPBP2B was completely saturated with 6.7 pmol (2.5 ng) of 3H-benzylpenicillin. The amount of binding to PBP2B increased linearly up to 2.5 ng and was saturated above 2.5 ng. In a competition assay, PBP2B was completely saturated by 0.1 μg/ml of penicillin G or methicillin/ml, as subsequent binding of 3H-benzylpenicillin was inhibited.

FIG. 4.

Penicillin binding assay (A) and competition assay (B) of rPBP2B. rPBP2B (0.15 μg) was mixed with various amounts of 3H-benzylpenicillin (lanes: A, 10 ng; B, 5 ng; C, 2.5 ng; D, 1.25 ng; E, 0.6 ng; F, 0.3 ng; G, 0.15 ng; H, 0 ng) as described in Materials and methods. After detection by fluorography, the bands on the film were scanned. The degree of saturation was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. For the competition assay, various concentrations of methicillin or penicillin G (lanes: 1, no additives; 2, 0.005 μg/ml; 3, 0.01 μg/ml; 4, 0.1 μg/ml) were incubated with rPBP2B, followed by incubation with 3H-benzylpenicillin.

Immunoprecipitation.

Since PBP2 and PBP2B had similar molecular masses and penicillin binding activities, we tried to demonstrate the expression of PBP2B in S. aureus COL and RN450 by immunoprecipitation. First, we tested for possible cross-reactivity of both proteins against anti-rPBP2B or anti-PBP2 serum (Fig. 5). Anti-PBP2 and anti-rPBP2B serum did not cross-react with rPBP2B and rPBP2, respectively. With anti-rPBP2B as the primary serum, a protein band of the expected size was detected in the sample immunoprecipitated with anti-rPBP2B serum from the COL membrane fraction but not in the sample immunoprecipitated with preimmune serum (Fig. 5B). With anti-PBP2 as the primary serum, no protein bands were detected in samples immunoprecipitated with either anti-rPBP2B serum or preimmune serum (Fig. 5A). These results clearly demonstrate that anti-PBP2B specifically recognizes PBP2B but not PBP2. This indicates that the protein immunoprecipitated with the antiserum is the PBP2B protein. With anti-PBP2B serum, the one radioactive band corresponding to the molecular mass of PBP2B was extracted from the 3H-benzylpenicillin-pretreated membrane fraction, while no radioactive band was extracted with preimmune serum (Fig. 5C). With the RN450 strain, we had the same results as with the COL strain (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Immunoblotting and fluorography of immunoprecipitation samples with anti-rPBP2B serum or preimmune serum. Western blotting was performed with anti-PBP2 serum (A) or anti-rPBP2B serum (B) as a primary antibody. Fluorography (C) was performed with anti-rPBP2B serum and 3H-benzylpenicillin-reacted membrane fraction. Immunoprecipitation was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: A, membrane fraction of strain COL; B, immunoprecipitation with preimmune serum; C, immunoprecipitation with anti-rPBP2B serum; D, recombinant PBP2B; E, recombinant PBP2. Standard molecular mass markers are indicated on the left.

Localization of PBP2B.

By using fractionation assays, PBP2B was found to localize mainly in the membrane fraction, not in the supernatant, cell wall, or cytoplasm (data not shown).

Comigration of PBP2 and PBP2B.

Figure 6A shows that rPBP2 and rPBP2B comigrated in polyacrylamide gel. When rPBP2 and rPBP2B were mixed and loaded, we found only a single band detected by immunoblotting and Coomassie staining. Immunoblotting of membrane fractions of various strains with anti-PBP2 or anti-PBP2B showed that PBP2 and PBP2B were both found in all of the strains tested and both proteins migrated to the same position (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Comigration of S. aureus PBP2 and PBP2B. (A) rPBP2B (lane 1), rPBP2 (lane 2) and rPBP2B plus rPBP2 (lane 3) were loaded on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel, and immunoblotting was performed with anti-rPBP2B, anti-PBP2, or both sera. The left panel shows Coomassie straining after SDS-PAGE. (B) Membrane fractions were prepared from eight MRSA and four MSSA strains as described in Materials and Methods. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-rPBP2B or anti-PBP2 serum. Lanes: a, MRSA COL; b, MRSA KSA7; c, MRSA KSA9; d, MRSA KSA11; e, MRSA KSA14; f, MRSA KSA16; g, MRSA KSA17; h, MRSA KSA19; i, MSSA KSA4; j, MSSA KSA24; k, MSSA FDA209P; l, MSSA CowanI; m, rPBP2; n, rPBP2B.

Identification of the PBP2B gene among various strains.

We detected a single PCR-amplified DNA fragment (about 780 bp) corresponding to the size (783 bp) calculated from the DNA sequence of the ISP3 strain in all strains tested (data not shown). We cloned DNA fragments, amplified from the MRSA COL strain and the MSSA RN450 strain, into the pGEM-T Easy vector. The DNA sequences of these two fragments matched perfectly with that of the corresponding portion of the ISP3 strain (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that S. aureus has another PBP, PBP2B, that has not been previously demonstrated. When PBPs are identified by fluorography in S. aureus, using radiolabeled penicillin, four bands (PBP1 to -4) are generally found. The molecular mass of PBP2B is 77.2 kDa, while that of PBP2 is 80.3 kDa, so it is difficult to distinguish these two proteins by fluorography of a one-dimensional gel. We found a gene, pbpF, encoding a putative PBP (PBP2B) from S. aureus genome sequence data. Based on the DNA sequence of pbpF, we demonstrated by the immunoprecipitation method that PBP2B was expressed and had penicillin binding activity in S. aureus. We performed the immunoprecipitation with the membrane fraction of an MRSA strain, COL, and obtained a result similar to that of MSSA strain RN450 membrane preparations (data not shown). Chambers and Miick reported that two penicillin binding peptides of PBP2 were identified by two-dimensional electrophoresis in a methicillin-susceptible strain (5). They divided PBP2 into two peptides, acidic and basic. The isoelectric point of PBP2 is 9.18, while that of PBP2B is 9.76 from the deduced amino acid sequence. It is possible that PBP2B corresponds to the basic peptide. This PBP2 complex was also observed in glycopeptide-resistant S. aureus (16, 20). The increased production of PBP2 complex was considered to be associated with glycopeptide resistance. In these studies, two kinds of PBP2 bands reacting with radiolabeled penicillin were found in the membrane fraction. Though we could not differentiate these PBPs clearly in our experiments, the results suggested the presence of two distinct PBPs showing almost the same molecular weight.

The deduced PBP2B protein of S. aureus showed homology with high-molecular-weight PBPs, especially PBP2 or PBP2B, in other species. Like those of other high-molecular-weight PBPs, the N-terminal region of PBP2B possesses a hydrophobic stretch, suggesting it is a membrane-spanning region. It has been reported that E. coli PBP2 is attached to the cell membrane as an ectoprotein by an N-terminal hydrophobic region with the single peptide uncleaved (1). The molecular mass of PBP2B detected in the S. aureus membrane fraction by Western blotting analysis was calculated as 70 kDa, suggesting that the signal sequence of PBP2B might be cleaved in vivo. The recombinant PBP2B without the membrane-spanning region still possesses penicillin binding activity, implying that this region is not associated with the binding activity. Similarly, PBP2′, with its N-terminal membrane-spanning region truncated, retains penicillin binding activity (28).

Among high-molecular-weight PBPs, three conserved motifs which are typically observed in PBPs and β-lactamases are found in the C-terminal halves of the proteins as a transpeptidase domain (12, 13, 18, 23). A putative transpeptidase domain was also found in the C-terminal half of the PBP2B amino acid sequence. Recently, C. Goffin and J.-M. Ghuysen reported the classification of all multimodular PBPs (10). PBP2B of S. aureus is a class B5 PBP, like S. pneumoniae PBP2B, S. thermophilus PBP2B, and B. subtilis PBP2A. The function of class B5 PBPs remains unknown. PBP2′ of MRSA, a class B1 PBP, is considered to have a transglycosylase domain in the N-terminal-half region because of the homology with PBP2 and PBP3 of E. coli (22). The non-penicillin-binding domain of class B5 PBPs, including PBP2B of S. aureus, does not have motifs for transglycosylase, so the function of the N-terminal half of PBP2B remains unknown. Further biochemical study will be needed to elucidate the function of PBP2B.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The contributions of members of the DNA-sequencing facility at Human Genome Sciences, Inc., are acknowledged. We thank Y. Huang for her help in the laboratory and K. Murakami, Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan, for anti-PBP2 serum.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists (grant no. 10770119) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and Health Sciences Research Grants for Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi H, Ohta T, Matsuzawa H. A water-soluble form of penicillin-binding protein 2 of Escherichia coli constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS Lett. 1987;226:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck W D, Berger-Bächi B, Kayser F H. Additional DNA in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and molecular cloning of mec-specific DNA. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:373–378. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.2.373-378.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beise F, Labischinski H, Giesbrecht P. Role of the penicillin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus in the induction of bacteriolysis by β-lactam antibiotics. In: Actor P, Daneo-Moore L, Higgins M L, Salton M R J, Shockman G D, editors. Antibiotic inhibition of bacterial cell surface assembly and function. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1988. pp. 360–366. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger-Bächi B, Strässle A, Kayser F H. Natural methicillin resistance in comparison with that selected by in-vitro drug exposure in Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;23:179–188. doi: 10.1093/jac/23.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers H F, Miick C. Characterization of penicillin-binding protein 2 of Staphylococcus aureus: deacylation reaction and identification of two penicillin-binding peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:656–661. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.3.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis N A C, Hayes M V, Wyke A W, Ward J B. A mutant of Staphylococcus aureus H lacking penicillin-binding protein 4 and transpeptidase activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;9:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontana R. Penicillin-binding proteins and the intrinsic resistance to beta-lactams in gram-positive cocci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;16:412–416. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgopapadakou N H, Liu F Y. Binding of β-lactam antibiotics of penicillin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus faecalis: relation to antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18:834–836. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.5.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goffin C, Ghuysen J-M. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1079–1093. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1079-1093.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henze U U, Berger-Bächi B. Staphylococcus aureus penicillin-binding protein 4 and intrinsic β-lactam resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2415–2422. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joris B, Ghuysen J-M, Dive G, Renard A, Dideberg O, Charlier P, Frere J-M, Kelly J A, Boyington J C, Moews P C, Knox J R. The active-site-serine penicillin-recognizing enzymes as members of the Streptomyces R61 DD-peptidase family. Biochem J. 1988;250:313–324. doi: 10.1042/bj2500313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly J A, Knox J R, Haiching Z, Frere J-M, Ghuysen J-M. Crystallographic mapping of beta-lactams bound to a D-alanyl-D-alanine peptidase target enzyme. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:281–295. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komatsuzawa H, Suzuki J, Sugai M, Miyake Y, Suginaka H. The effect of Triton X-100 on the in-vitro susceptibility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to oxacillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:885–897. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kornblum J, Hartman B J, Novick R P, Tomasz A. Conversion of a homogeneously methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus to heterogeneous resistance by Tn551-mediated insertional inactivation. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986;5:714–718. doi: 10.1007/BF02013311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreira B, Boyle-Vavra S, de Jonge B L M, Daum R S. Increased production of penicillin-binding protein 2, increased detection of other penicillin-binding proteins, and decreased coagulase activity associated with glycopeptide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1788–1793. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami K, Fujimura T, Doi M. Nucleotide sequence of the structural gene for the penicillin-binding protein 2 of Staphylococcus aureus and the presence of a homologous gene in other staphylococci. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;117:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oefner C, D’Arcy A, Daly J J, Guernator K, Charnas R L, Heinze I, Hubschwerien C, Winkler F K. Refined crystal structure of beta-lactamase from Citrobacter freundii indicates a mechanism for beta-lactam hydrolysis. Nature (London) 1990;343:284–288. doi: 10.1038/343284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds P E, Fuller C. Methicillin resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus; presence of an identical additional penicillin-binding protein in all strains examined. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;33:251–254. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shlaes D M, Shlaes J H, Vincent S, Etter L, Fey P D, Goering R V. Teicoplanin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus expresses a novel membrane protein and increases expression of penicillin-binding protein 2 complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2432–2437. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song M D, Wachi M, Doi M, Ishino F, Matsuhashi M. Evolution of an inducible penicillin-target protein in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by gene fusion. FEBS Lett. 1987;221:167–171. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spratt B G, Cromie K D. Penicillin-binding proteins of Gram-negative bacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:699–711. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugai M, Akiyama T, Komatsuzawa H, Miyake Y, Suginaka H. Characterization of sodium dodecyl sulfate-stable Staphylococcus aureus bacteriolytic enzymes by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6494–6498. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6494-6498.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomasz A, Drugeon H B, de Lencastre H M, Jabes D, McDougall L, Bille J. New mechanism for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: clinical isolates that lack the PBP 2a gene and contain normal penicillin-binding proteins with modified penicillin-binding capacity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1869–1874. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ubukata K, Nogorochi R, Matsuhashi M, Konno M. Expression and inducibility in Staphylococcus aureus of the mecA gene which encodes a methicillin-resistant S. aureus-specific penicillin-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2882–2885. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2882-2885.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada A, Watanabe H. Penicillin-binding protein 1 of Staphylococcus aureus is essential for growth. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2759–2765. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2759-2765.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu C Y E, Hoskins J, Blaszczak L C, Preston D A, Skatrud P L. Construction of a water-soluble form of penicillin-binding protein 2a from a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:533–539. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.3.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]