Abstract

Clinical relevance:

Objective assessment of near viewing behaviors performed in a laboratory setting showed that children demonstrate differing viewing distances and angles based on the type of task. Findings will contribute to our understanding of how near work influences myopia.

Background:

Evidence suggests that near working distance and viewing breaks are associated with myopia. The purpose of this study was to use an objective, continuously measuring range finding device to examine these viewing behaviors in children.

Methods:

Viewing distance, number of breaks, and head and eye angles were assessed in 16 non-myopic and 19 myopic children (ages 13.38 ± 4.14 years) using the Clouclip, an objective rangefinder, during five 15-minute near tasks, including a) passive reading and b) active writing on printed material, c) passive viewing and d) active engagement on an iPad, and e) active engagement on a cell phone. Height and Harmon distance were measured. Viewing behaviors were analyzed by task, refractive error group, and gender.

Results:

Mean viewing distances significantly differed by task (P < 0.001) and were highly correlated with children’s Harmon distance and height for all near tasks (P < 0.05), except for the active printed task (P > 0.05). Viewing distances did not differ by gender or refractive error group. During each task, mean number of viewing breaks was 2.6 ± 4.1 and did not vary between task (P = 0.92) or refractive error group (P = 0.65). Head declination and total viewing angle varied by type of near task (P < 0.001 for both).

Conclusion:

Children demonstrated differing viewing distances and viewing angles based on the type of near task they were performing. Viewing behaviors did not vary between myopic and non-myopic children. Findings will contribute to a better understanding of how near viewing behaviors can be quantified objectively and relationships with myopia.

Keywords: myopia, near work, refractive error, sensors, viewing angle, viewing distance

Introduction

The prevalence of myopia is increasing with 50% of the world population expected to be myopic by the year 2050.1 Any amount of myopia is associated with an increased risk of sight threatening ocular comorbidities, such as cataract, glaucoma, retinal detachment, and myopic maculopathy.2–4 Myopia represents a significant socioeconomic burden and cause of vision impairment and blindness.5,6 Identifying modifiable risk factors to prevent myopia is important to address the increasing prevalence.

Myopia is regulated by a complex interaction of genetics and environmental, behavioral, and optical factors,7 including time outdoors,8,9 light exposure,10,11 near work,12–14 and peripheral hyperopic defocus.15,16 Outdoor light exposure has been found to be protective against myopia onset.9,17,18 Rose et al. reported the highest odds ratio of myopia prevalence among children who spend low time outdoors and greater amount of time doing near work.19 Studies have shown that physical activity is not an independent risk factor for myopia.20,21 Slower myopia progression has been reported in summer months compared to winter months, which the authors hypothesized could be due to increased light exposure during summer accompanied by reduced academic pressure.22 Several studies show an association between the amount and duration of near work and myopia prevalence among children,23 adolescents,9 and university students.24 The defocus profile of near work in home environment has been found to be associated with myopia development in children.25 However, results regarding the influence of near work on myopia pathogenesis are conflicting, with several studies reporting no significant increased risk of myopia with increased near work.26–28 Inconsistencies across studies relating to a role of near work in myopia may be due to the subjective nature by which near work is traditionally assessed and quantified. Parent surveys are typically utilized to quantify near work; however, this method is limited by recall errors and parental biases.29,30 Other methods include diaries and the experience sampling methods, which are limited by compliance and low sampling rate. Surrogate methods such as level of education,31 number of books read,32 and occupation33 have also been used to infer near work.

Evidence suggests that near viewing behaviors, such as duration of each near viewing session, absolute viewing distance, and viewing breaks may be more relevant than overall duration of near work.34 In a cross sectional study of 12-year-old Australian children, continuous reading (>30 minutes) and a reading distance less than 30 cm were associated with a more myopic refraction.35 Li et al. reported a higher odds of myopia in Chinese school children if the reading distance was closer than 20 cm and if continuous reading was performed for more than 45-minute periods.36 Use of digital devices is another potential environmental risk factor for myopia.37,38

The aim of this study was to compare objectively measured viewing behaviors in non-myopic and myopic children during various near tasks using a continuously measuring spectacle-mounted rangefinder.

Methods

Children ages 6 to 18 years were recruited. Ethical approval was obtained from the Committee for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Houston, and all procedures followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, written parental permission and consent to enroll their children was obtained from parents, and written assent was obtained from each child.

All children had best corrected visual acuity of 6/7.5 or better and no history of ocular disease. Children with known history of strabismus or ocular surgery were excluded. Children with excessive phoria or any tropia on unilateral and alternating cover tests were excluded. Harmon distance was measured as the distance from the elbow to the middle knuckle while a fist was made, the elbow was placed on a desk, and the arm upright.39 Non-cycloplegic autorefraction (WAM-5000, Grand Seiko, Japan) and biometry were measured (LenStar LS900, Haag-Streit, Switzerland). Five measurements were taken in each eye and averaged. Accommodative responses were measured for demands of 2, 3, 4, and 5 D using a letter target and open field autorefractor (WAM-5000) to ensure that excessive accommodative lags were not present. Refractive errors greater than 0.5 D were corrected with a trial lens, and the accommodative response was calculated for each demand as the change in refraction from distance viewing.

Children were classified as myopic (spherical equivalent refractive error of right and left eyes ≤ −0.50 DS, with at least one eye measuring −0.75 DS myopia) or non-myopic (mean spherical equivalent refractive error from right and left eyes of +1.25 to −0.50 DS, with no eye exhibiting −0.75 D or greater myopia). Children with hyperopia (spherical equivalent refractive error ≥ +1.50 D) and with high myopia (≤ −6.00 D) were excluded to avoid potential confounding effects on viewing behavior.

Procedures

The Clouclip (Glasson Technology Co Ltd, HangZhou, China) is a lightweight cordless spectacle-mounted device that measures distance every 5 seconds using infrared time-of-flight technology.40,41 The tracking beam diameter is 25 degrees and is angled 10 degrees inferiorly, with a reported range of 5 to 120 cm. The Clouclip goes to sleep mode if no movement is detected for 40 seconds. All Clouclip devices (n = 11) were tested and calibrated.42 Devices were charged and mounted on the right temple of the child’s habitual spectacle frame for myopes or of a frame with plano lenses for non-myopes or myopes wearing contact lenses. The Clouclip was mounted with an additional 10 degrees downward tilt to reliably capture the viewing targets, as described previously.42

The Clouclip has been previously validated and was found to reliably measure viewing distances for both printed (matte) and electronic (glossy) targets with good repeatability.42 Distance measures are robust for up to 60 degrees of target tilt respective to the measurement beam. When mounted on a spectacle frame, the measurement beam is aligned with axis of the head, which may produce small misalignment errors from the line of sight. Care was taken to mount the Clouclip such that the anterior surface of the device, emitting the infrared tracking beam, was aligned with the corneal surface so that eye-to-target and Clouclip-to-target distances were similar.

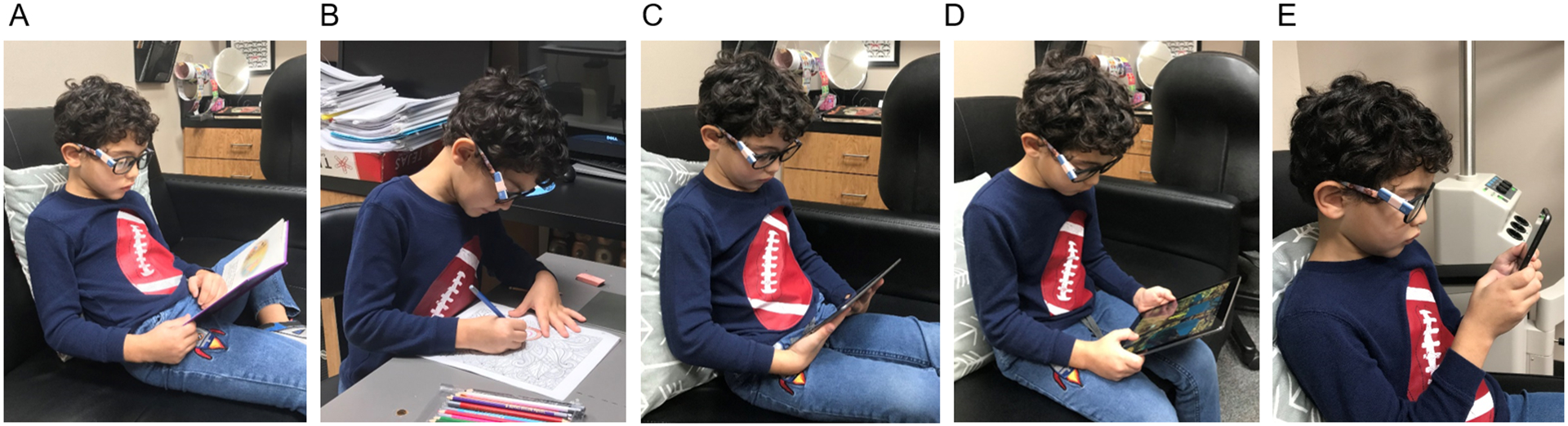

The order of five 15-minute tasks was randomized and included a) passive reading of printed material b) active writing on printed material, c) passive viewing on an iPad (iPad Air 2, 9.7 inch screen), d) active engagement on the iPad, and e) active engagement on a cell phone (Google Pixel, 5 inch screen) (Figure 1). For passive reading of printed material, children read age-appropriate books (size 22.5 cm × 14.5 cm and font 8.5–12 point) at their habitual reading distance while sitting in a chair. For active printed tasks, children were seated at a desk and completed word puzzles, Sudoku, and coloring templates printed on white A4 paper. Tasks on the iPad and cell phone were performed while children were seated in a chair and holding the device in their hands. For passive viewing on an iPad, children watched a video on YouTube, and for active engagement on the iPad and cell phone, children played a game (Temple Run, Imangi Studio, www.templerun.com). Room illuminance was approximately 400 lux.

Figure 1.

Near tasks included A) passive printed task (reading), B) active printed task (writing), C) passive electronic task on iPad (watching videos), D) active electronic task on iPad (playing a game), and E) active electronic task on cell phone (playing a game)

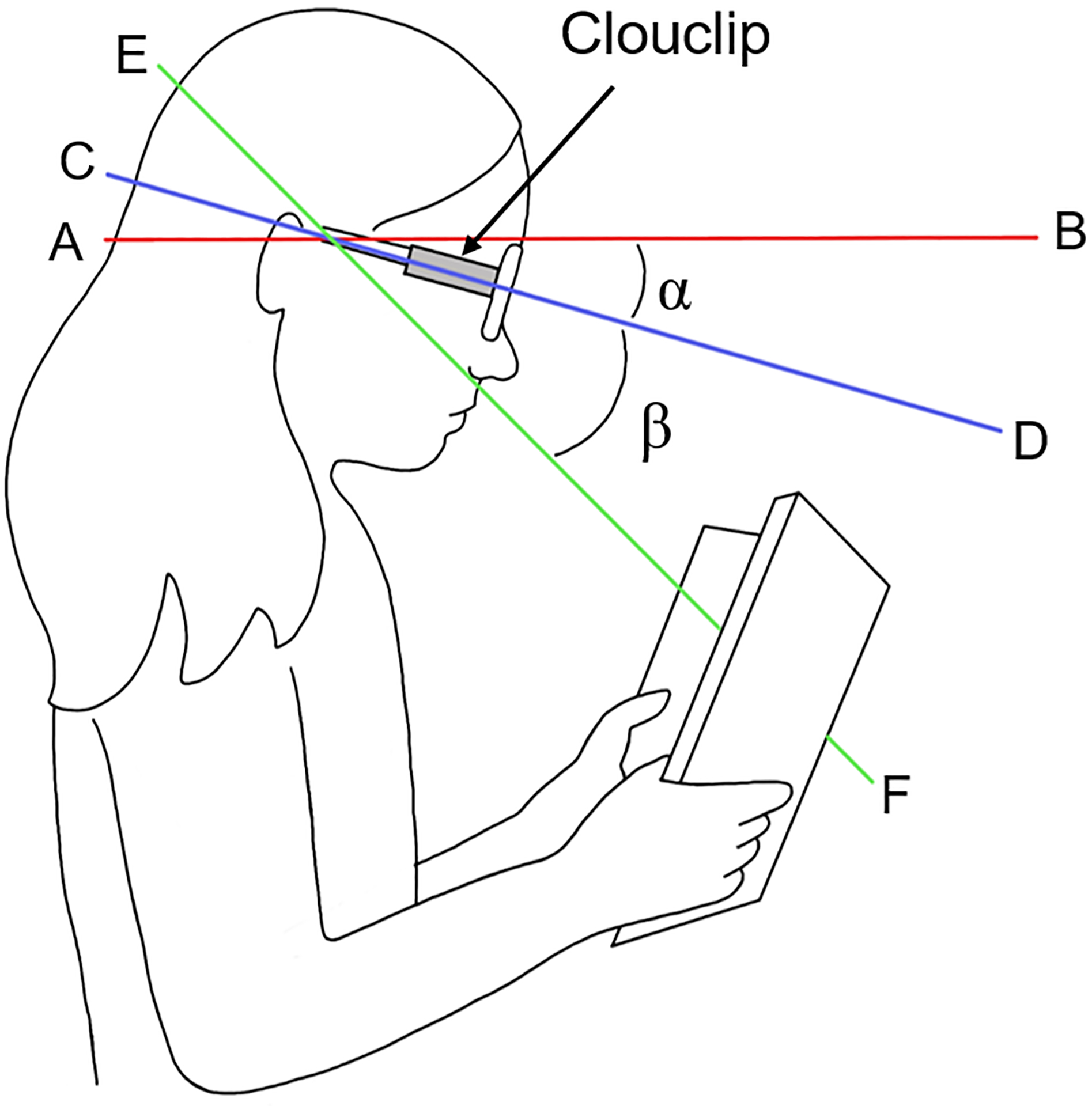

At the midpoint of each 15-minute task, viewing distance was measured using a ruler, and three photos were captured. Children were informed that pictures would be captured and were instructed to continue their task and try to pay no attention to the pictures; the camera did not flash or make sound in order to minimize disturbances to the child. One good quality photo was chosen, and three lines were drawn using MS Paint to mark head angle, eye angle, and straight-ahead horizontal line. Photos were imported into ImageJ 1.53e software (National Institute of Health, USA), and head angle, eye angle, and total viewing angle were determined using Angle tool (Figure 2). Head angle was defined as the forward downward angle of the head relative to a horizontal straight-ahead direction (angle α). Eye angle was defined as the angle of the eye relative to the right temple of the glasses (angle β). Total viewing angle was defined as the sum of head angle and eye angle. Viewing breaks were quantified as the number of occasions that the child looked away from the near task, such that viewing distance was ≥ 1 meter for at least 5 seconds.

Figure 2.

Measurement of head and eye angle; line AB: straight ahead horizontal; line CD: along the temple of the glasses; line EF: direction of line of sight; angle α: angle of head tilt; angle β: angle of eye gaze; angle α+β: total viewing angle

Analysis

Data were uploaded to a cloud then downloaded from the server and consisted of time-tagged viewing distance. The data were separated by task, and for each task, mean viewing distance and number of viewing breaks were determined. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., NY, USA). All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Two-way ANOVAs were utilized to assess distance and number of viewing breaks by task and refractive error group. Mean viewing distances were compared based on media (paper versus electronic) and engagement (passive versus active) using paired t-test. Viewing distances recorded over each 15-minute task were binned into three time periods, 0 to <5 minutes, 5 to <10 minutes, and 10 to 15 minutes, and compared using a repeated measures ANOVA. Head angle, eye angle, and total viewing angle were compared between task and refractive error group using repeated measures ANOVA. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were performed when indicated. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

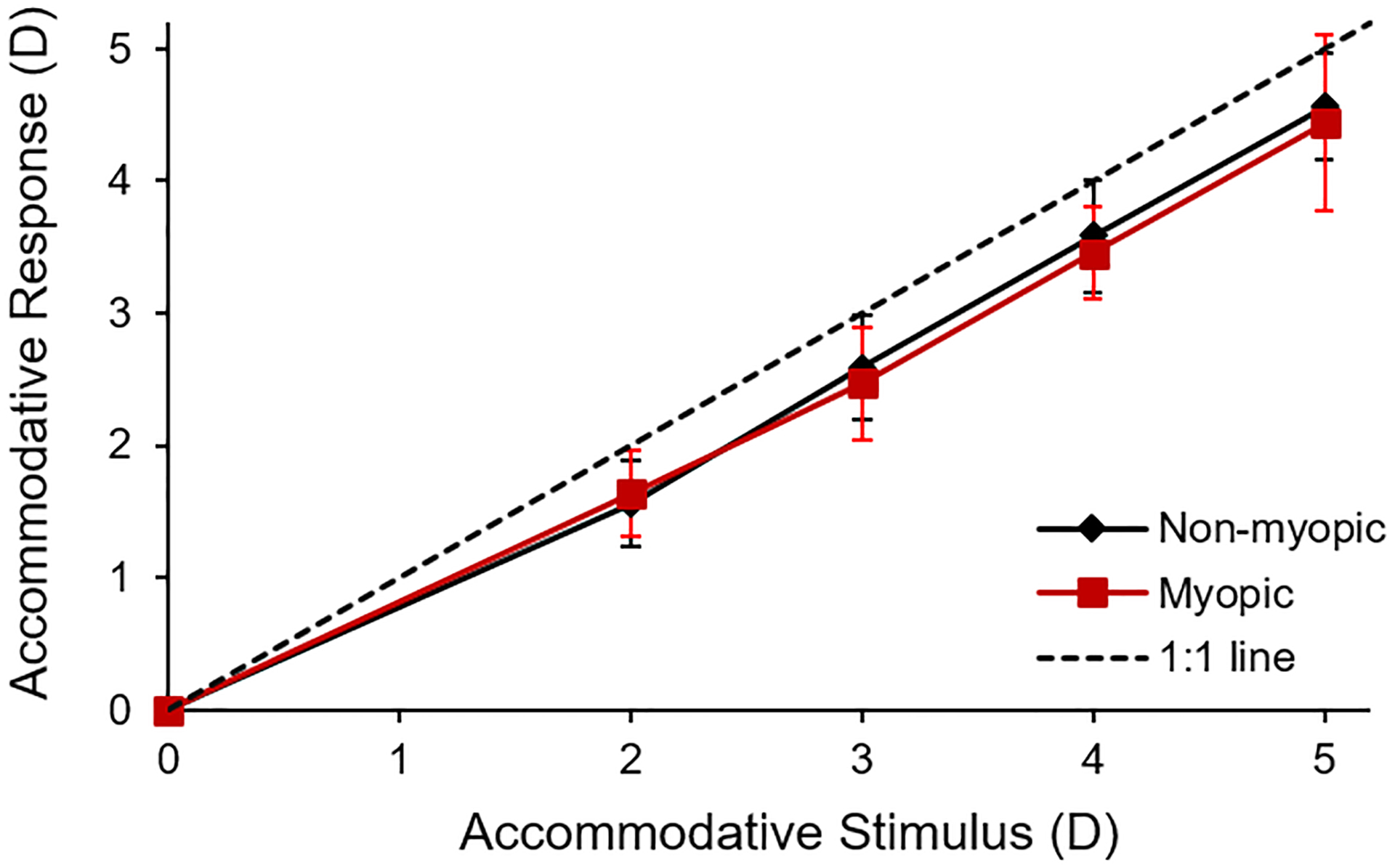

Thirty-five children, ages 13.4 ± 4.1 years (range: 6.1 to 18.6 years) participated (Table 1). Mean height and Harmon distance was 150.0 ± 16.9 cm and 31.7 ± 4.0 cm, respectively. Axial lengths and spherical equivalent refractive errors were similar between right eye and left eyes (P = 0.26 and 0.65, respectively); only data from right eyes are considered further. Mean spherical equivalent refractive errors in non-myopes (n = 16) was +0.03 ± 0.37 D (range −0.06 to +0.43 D), and in myopes (n = 19) was −2.65 ± 1.82 D (range −0.68 to −5.75 D). Myopes had longer axial length than non-myopes (P = 0.003). Age, height, and Harmon distance were similar between refractive error groups (P = 0.23, 0.43, and 0.36, respectively). There were no significant differences in the accommodative response or lag between refractive error groups (P > 0.05 for all, Figure 3).

Table 1.

Ocular and biometric profile of children in non-myopic and myopic groups. P values are shown for unpaired t-test between refractive error groups;

| Parameter | Non-Myopes (n=16) | Myopes (n=19) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.46 ± 4.24 | 14.15 ± 4.00 | 0.23 | |

| Gender | 7 M:9 F | 6 M:13 F | 0.45 | |

| Axial length (mm) | 23.33 ± 0.69 | 24.34 ± 1.12 | 0.003* | |

| Spherical equivalent refractive error (D) | +0.03 ± 0.37 | −2.65 ± 1.82 | <0.0001** | |

| Height (cm) | 147.51 ± 17.70 | 152.13 ± 16.37 | 0.43 | |

| Harmon distance (cm) | 30.96 ± 3.88 | 32.23 ± 4.10 | 0.36 | |

< 0.05,

< 0.001

Figure 3.

Accommodative response (D) for non-myopes (black line) and myopes (red line) at 2, 3, 4, and 5 D target demands; dashed line indicates the one-to-one line

The Clouclip went to sleep mode on 0.5 ± 1.1 occasions per child, and was not significantly different by task (P = 0.07) or by refractive error group (P = 0.50). During each 15-minute task, valid data for non-myopes (13.9 ± 2.6 minutes) and myopes (14.1 ± 2.2 minutes) was similar (P = 0.73).

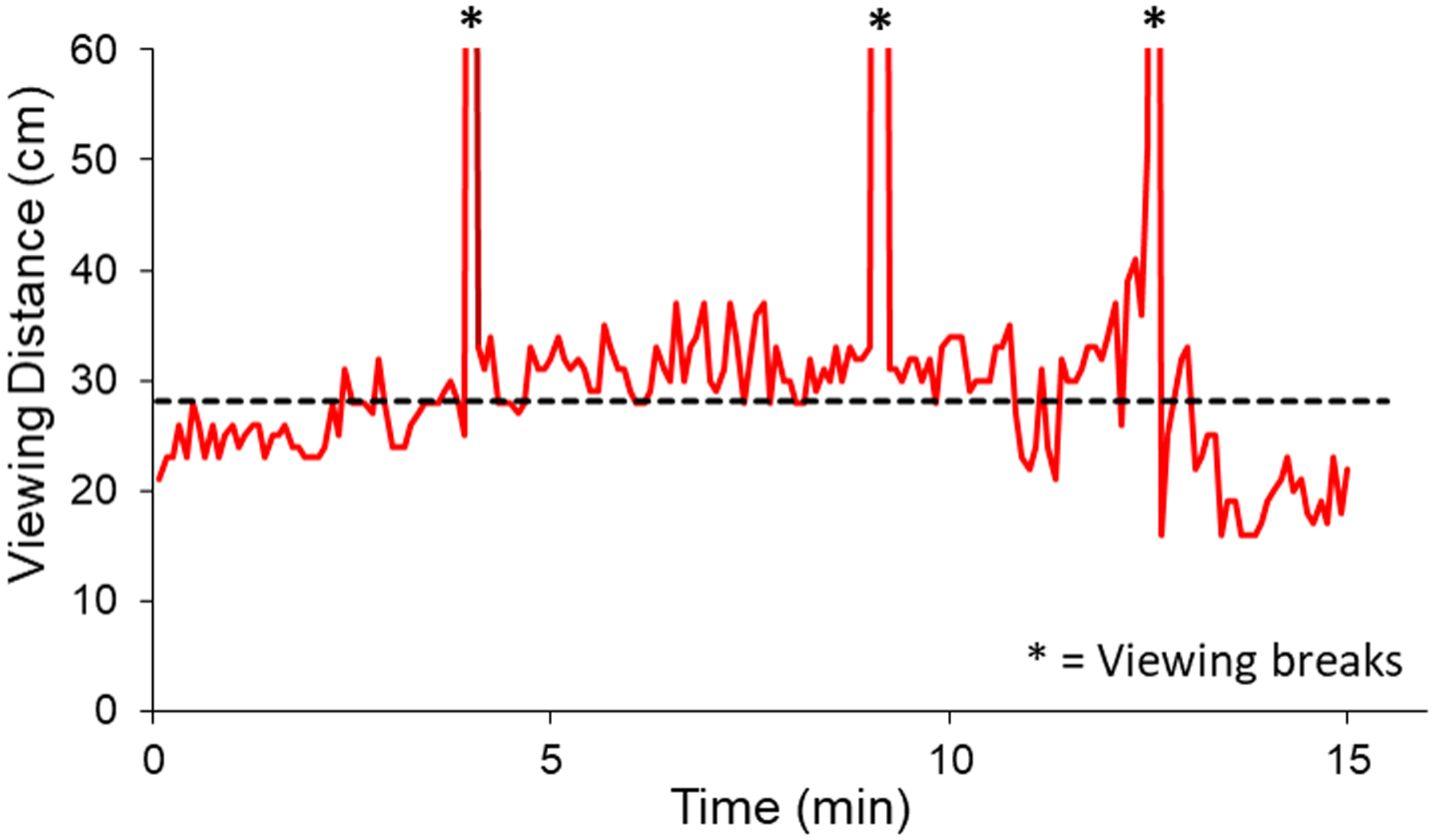

A representative trace of viewing distance during the 15-minute active electronic task is shown in Figure 4, and mean viewing distances, breaks, and angles are shown in Figure 5. Mean viewing distances are presented in Table 2. Viewing distances recorded by Clouclip were similar to distances measured with the ruler except for the active printed task (Clouclip-recorded distance closer by 2.0 cm, P = 0.001) and electronic task (Clouclip-recorded distance closer by 2.3 cm, P = 0.007). These differences are likely due to the fact that the ruler was used to measure at a single time point where as the Clouclip measures were summed over 15 minutes.

Figure 4.

Representative trace of viewing distance recorded by the Clouclip for one child performing the 15-minute active electronic iPad task; dashed line represents mean viewing distance excluding breaks; * = viewing breaks

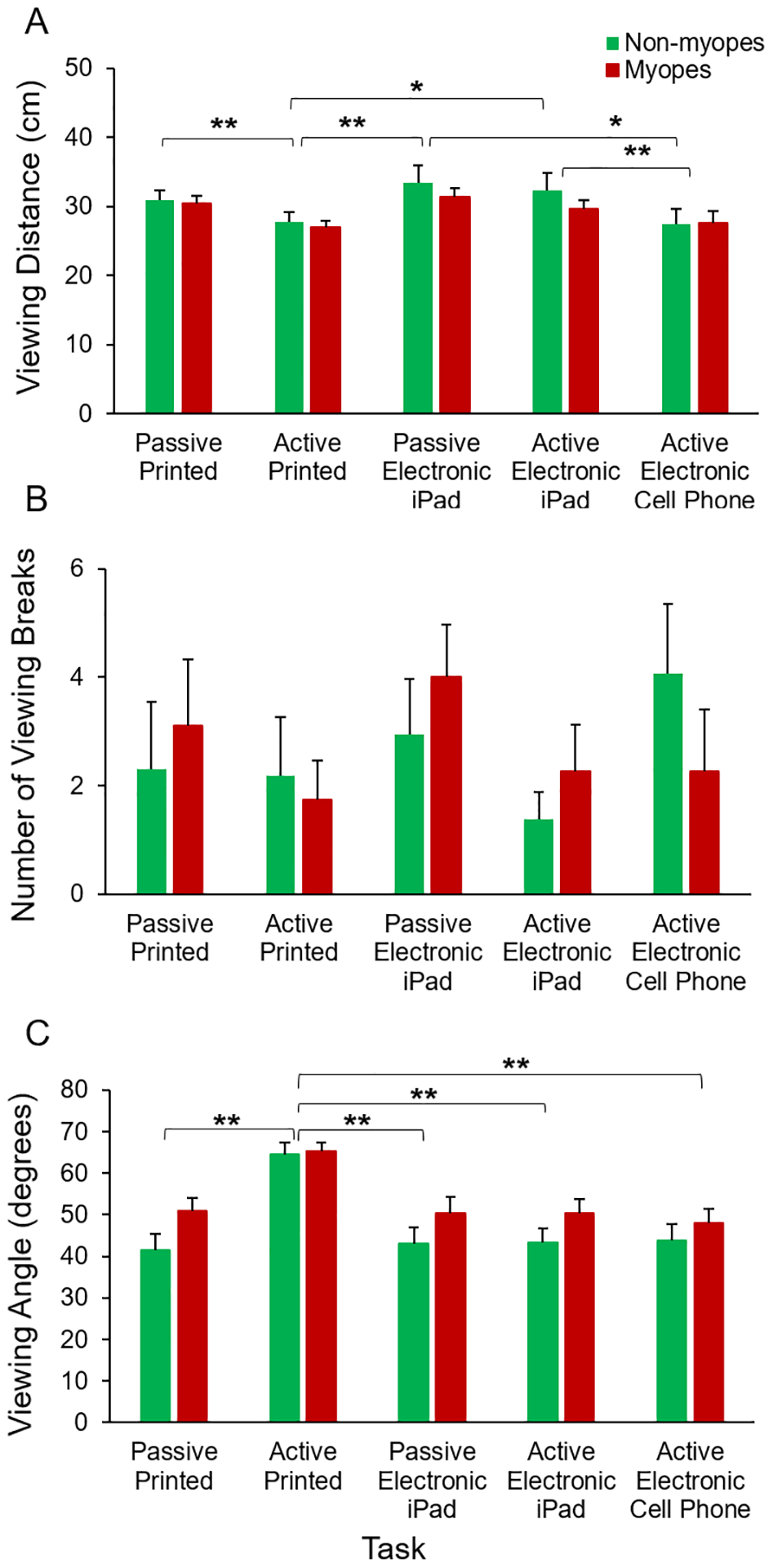

Figure 5.

A) Mean viewing distance (cm), B) number of breaks, and C) total viewing angle (degrees) for each task for non-myopes (green) and myopes (red); *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001 for post-hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons between tasks

Table 2.

Viewing distances (cm) for five near tasks for non-myopes and myopes. P value is shown for post-hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons between refractive error groups

| Task | Non-Myopes (N = 16) | Myopes (N = 19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive printed | 30.9 ± 5.4 | 30.4 ± 4.5 | 0.77 |

| Active printed | 27.8 ± 5.7 | 26.9 ± 4.4 | 0.61 |

| Passive electronic iPad | 33.4 ± 10.0 | 31.3 ± 5.7 | 0.43 |

| Active electronic iPad | 32.4 ± 9.8 | 29.7 ± 5.5 | 0.31 |

| Active electronic cell phone | 27.4 ± 9.2 | 27.6 ± 7.9 | 0.94 |

Mean viewing distance differed significantly by task (P < 0.001), but not by refractive error group (P = 0.55) or gender (P = 0.32). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that viewing distance for the active printed task was significantly less than for the passive printed (P = 0.009), passive electronic iPad (P = 0.002), and active electronic iPad (P = 0.02) tasks. Viewing distance for the active cell phone task was significantly less than for the active electronic iPad task (P = 0.02) and passive electronic iPad task (P = 0.01). Although a trend for shorter viewing distance with increasing negative spherical equivalent refractive error was observed, the relationships did not reach significance (P > 0.05 for all).

Children took an average of 2.6 viewing breaks per task. The number of viewing breaks was not significantly different by task (P = 0.92) or by refractive error group (P = 0.65).

Mean viewing distance was not significantly different for printed tasks (29.0 ± 3.0 cm) versus electronic tasks (30.2 ± 7.1 cm, P = 0.15). However, mean viewing distance for active tasks (28.6 ± 6.0 cm) was significantly less than for passive tasks (31.5 ± 5.8 cm, P = 0.001).

To assess change in viewing distance over time, viewing distances for each 15-minute task were binned into three time periods (0 to <5 minutes, 5 to <10 minutes, and 10–15 minutes). Viewing distances did not differ across the three time periods and were similar between non-myopes and myopes (P > 0.05 for all).

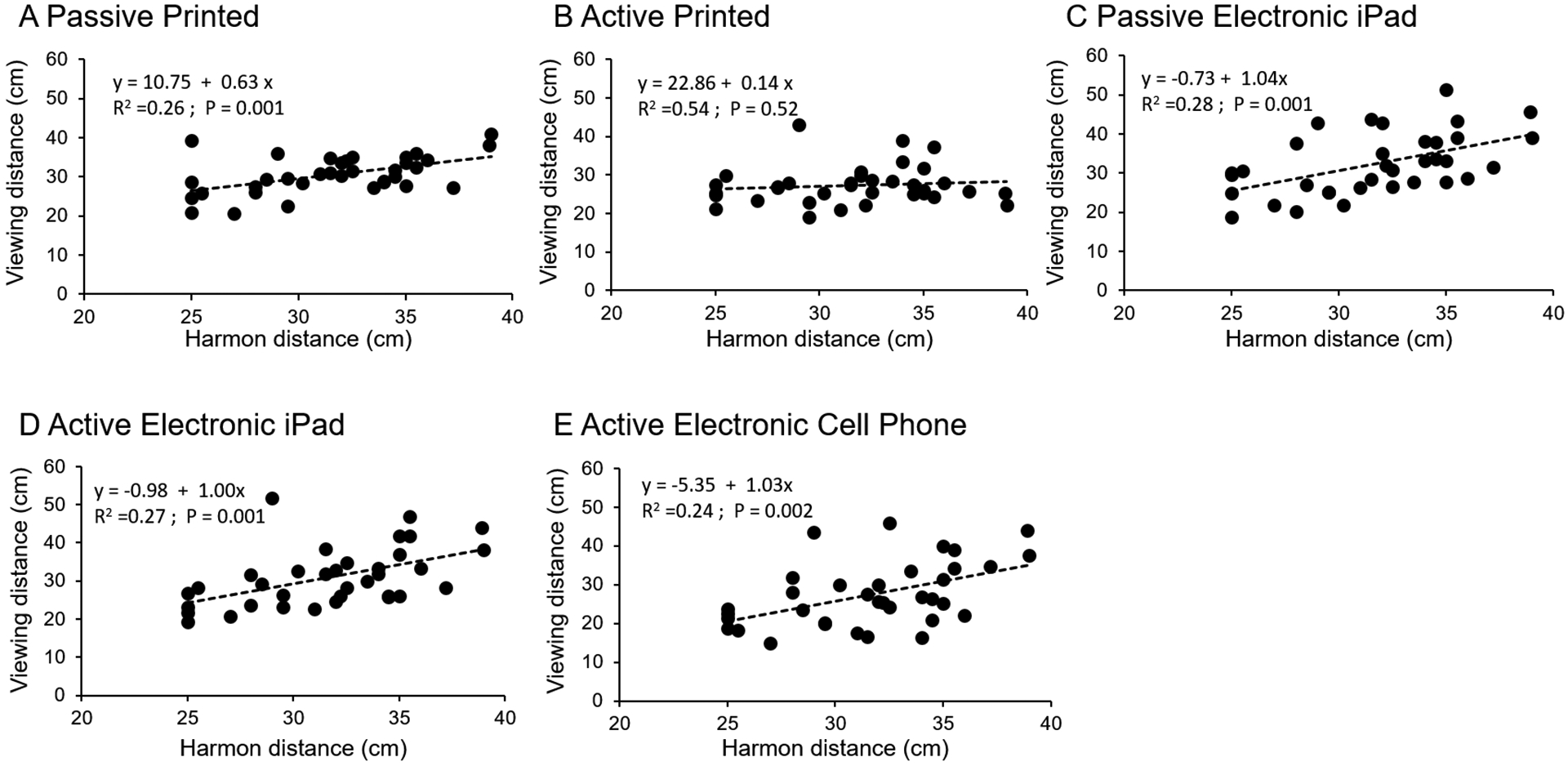

A significant positive correlation was found between Harmon distance and mean viewing distance for all tasks (P < 0.05 for all), except for the active printed task (P = 0.52, Figure 6). Similarly, a significant positive correlation was seen between height and mean viewing distance for all tasks (P < 0.05 for all), except for active printed task (P = 0.53). There were no differences by refractive error group (P > 0.05 for all). A significant positive correlation was seen between height and Harmon distance (R2 =0.90, P < 0.001). Multiple regression analysis adjusting for height and Harmon distance showed a significant correlation between height, Harmon distance, and viewing distance for all tasks (P < 0.05 for all), except for the active printed task (P = 0.81).

Figure 6.

Linear relationships (dashed line) between Harmon distance and mean viewing distance for A) passive printed, B) active printed, C) passive electronic iPad, D) active electronic iPad, and E) active cell phone tasks

Mean head, eye, and total viewing angle varied by task (P < 0.001 for all), but not by refractive error group or gender (P > 0.05 for all, Table 3). Head angle for the active printed task was significantly greater (i.e., more declined) than all other tasks (P < 0.001 for all). There was a significant negative correlation between viewing distance and head angle for the active printed task (R2 = 0.31, P < 0.001); closer viewing distances were associated with greater head angle. There was a weak, but significant, positive correlation between viewing distance and head angle for the active electronic cell phone task (R2 = 0.12, P = 0.04). For the other three tasks, there were no associations between head angle and viewing distance (P > 0.05 for all). A significant positive correlation was found between eye angle and viewing distance for active printed tasks (R2 = 0.23, P = 0.003) and active electronic cell phone use (R2 = 0.35, P < 0.001). Total viewing angle was significantly greater for the active printed task compared to the other tasks (P < 0.001 for all). A significant positive correlation was found between total viewing angle and viewing distance only for active electronic cell phone use (R2 = 0.38, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Head, eye, and total viewing angles (degrees) for each task for non-myopes and myopes.

| Task | Parameters | Non-Myopes (N = 16) | Myopes (N = 19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive printed | Head angle | 20.4 ± 11.1 | 29.7 ± 13.5 | 0.03* |

| Eye angle | 20.9 ± 9.4 | 21.3 ± 9.3 | 0.90 | |

| Total | 41.3 ± 16.0 | 51.0 ± 13.8 | 0.06 | |

| Active printed | Head angle | 44.0 ± 14.6 | 44.7 ± 8.5 | 0.87 |

| Eye angle | 20.4 ± 9.4 | 20.6 ± 8.9 | 0.94 | |

| Total | 64.4 ± 12.2 | 65.3 ± 9.4 | 0.81 | |

| Passive electronic iPad | Head angle | 23.9 ± 13.6 | 32.8 ± 16.2 | 0.09 |

| Eye angle | 19.1 ± 7.6 | 17.6 ± 8.0 | 0.26 | |

| Total | 43.0 ± 16.5 | 50.4 ± 17.0 | 0.19 | |

| Active electronic iPad | Head angle | 24.1 ± 12.3 | 33.3 ± 7.9 | 0.04* |

| Eye angle | 19.2 ± 6.5 | 17.1 ± 6.5 | 0.77 | |

| Total | 43.2 ± 13.7 | 50.4 ± 15.3 | 0.16 | |

| Active electronic cell phone | Head angle | 26.4 ± 11.8 | 32.1 ± 13.4 | 0.19 |

| Eye angle | 17.4 ± 8.5 | 15.9 ± 9.2 | 0.61 | |

| Total | 43.8 ± 16.3 | 48.0 ± 15.2 | 0.43 |

P < 0.05 are shown for independent samples t-tests between refractive error groups

Discussion

With recent advances in wearable sensor technology, it is possible to capture temporal patterns of near work pertinent to myopia research, such as absolute viewing distance, duration of continuous near work, and number of viewing breaks.36,41,43–46 In this study, viewing behaviors were assessed in children during five 15-minute near tasks that incorporated a range of common printed and electronic near activities. Viewing distances were shortest for active writing and cell phone tasks, and shorter for the cell phone compared to the iPad. There were no differences in viewing distance, number of breaks, or head, eye, and total viewing angles between non-myopes and myopes or by gender. Height and Harmon distances were significantly correlated with each other, and both were associated with viewing distances for all near tasks except for the active writing task, which was the only task in which the material was placed on a desk rather than hand held. There were no significant variations in viewing distance over time for each task. The greatest vertical head declination was seen for the active writing task.

Evidence in animal models suggests that viewing breaks or intermittent periods of fixation changes could be protective against myopiagenic effects of defocus. In infant monkeys, one hour of unrestricted vision countered myopiagenic effects of diffuser lenses worn for the rest of the day.47 In chicks, brief interruptions of form deprivation with normal viewing breaks resulted in reduced magnitude of myopia.48 In tree shrews reared with defocus lenses, a brief daily period of unrestricted vision for 45 minutes counteracted lens induced myopiagenic defocus for the remaining 13 hours and 15 minutes of the day.49 These findings suggest that viewing breaks during sustained near work might be beneficial to minimize the myopiagenic effects of hyperopic defocus on the peripheral retina from prolonged near work. In the current study in children, there were no differences in the number of viewing breaks taken during these short-term near tasks, and no differences by refractive error group. Wearing the Clouclip device for longer duration and in home and school environments will provide more insight into how viewing breaks influence myopia.

Previous studies have used wearable rangefinders to objectively and precisely measure near viewing distances in relation to refractive error in a lab setting.50,51 An ultrasonic device attached to a head band was used to log near work distances at 1 Hz in adults, and the authors found that high myopes had a significantly shorter working distance than low myopes and non-myopes.51 For the 10 minute reading session, subjectively reported viewing distances were not correlated with objectively determined distances.51 Hartwig et al. used a helmet-mounted eye tracker and electromagnetic motion sensor to measure working distance and eye and head movements in adults during two minutes each of reading on a screen, reading a printed book, and writing on paper, and found a positive correlation between mean spherical equivalent refractive error and working distance for reading a book.50 In the current study, however, no significant correlations were observed between spherical equivalent refraction and viewing distances for any near tasks. Different findings between studies could be due to differences in the population tested; here, participants were younger and no high myopes were included.

In addition to working distance, near work posture is also important factor to consider. In a previous study, a shorter viewing distance and increased head declination were observed with reading and writing tasks performed on the desk compared to reading on an arm chair as determined using photographs.52 Bao et al. used an electromagnetic motion-tracking system to measure working distance and near-vision posture in Chinese children during three different near tasks that included playing a handheld video game, reading, and writing at a desk.53 They reported a significant difference in working distance and head declination between near tasks, with closest working distance and greatest head declination for video games, followed by writing and reading tasks, similar to our study. Shortened working distances and increased head declination was reported for reading tasks over 3 minutes, highlighting the importance of more frequent sampling of near work behaviors for myopia studies.

In a previous study, a reading and writing distance of approximately 27 cm was found in children when they performed near tasks at a school desk,54 closely matching the viewing distance recorded for the active printed task in our study (27.3 ± 5.0 cm). Another study quantified viewing distance and eye angle from photographs acquired at 10-second sampling intervals over three 3-minute near tasks and found a mean viewing distance of 20 to 30 cm.52 The slightly longer distances observed here may be due to the older age of children in the current study. Head and eye angles in the previous study closely matched with the angles measured here.

We found that active tasks were performed at a closer distance compared to passive tasks. The decrease in viewing distance for active tasks might be due to increased attentional demand and the necessity to use hands to write on the paper or actively navigate the screen. Therefore, to get a complete near work profile, it is important to consider task-related demands in terms of concentration and physical interaction based on type of media. Shorter working distance has previously been found to be associated with an increase in accommodative lag and variability leading to increased hyperopic defocus.55,56 Over an extended period of near work, these factors might integrate temporally, making children working at a closer distance more susceptible to myopia.57

There are several factors that may have influenced working distances and viewing angles measured in this experiment. Children were somewhat limited in position based on the experimental set up in the lab, which included a freestanding chair for reading and electronic tasks, and a fixed desk and chair for the active printed task. Children were allowed to adjust the height of the desk and chair at the beginning of the active printed task. However, in children’s homes, they likely work at a variety of positions in addition to sitting in a chair, such as laying in either prone or supine positions. The use of spectacle frames in non-myopic children could have influenced viewing behaviors, compared to myopes who were accustomed to spectacle wear. Additionally, children’s behaviors may have been biased from being aware that they were being observed. Future studies taking place in habitual working environments and encompassing broad range of near activities would be informative.

A limitation in this study was that refractive status was determined using non-cycloplegic autorefraction. To overcome this limitation, an open-field auto refractor was used. The Clouclip device also presents some limitations. The device goes to “sleep mode” if the tri-axial accelerometer does not detect movement for 40 seconds, resulting in data loss of about 2.5 minutes on each occasion. Such occasions were observed in those children who were extremely still and did not move their head during near tasks. However, a similar number of occasions in which the device went to sleep mode was observed in non-myopes and myopes. Another limitation of the Clouclip is that the beam may not necessarily align with the line of sight, as the Clouclip is mounted on the spectacle temple and eye position is not tracked. Additionally, the sampling rate of Clouclip is every 5 seconds and short viewing breaks will be missed. Future studies could incorporate video recording to test the accuracy of viewing break quantification. Further advances in tracking technology with increased sampling rate will be useful in getting precise measurement of viewing behaviors; however, this may require larger, less portable hardware.

Conclusion

Viewing behaviors measured continuously and objectively differed with the type of near task performed. Children exhibited a shorter working distance for tasks in which they were actively engaged, regardless of whether the task was on printed or electronic media. There were no differences in viewing distances, number of breaks, or head, eye, and total viewing angles between non-myopic and myopic children. Future studies using objective methods for longer durations, in children’s habitual environment, and with a range of refractive errors will provide a better understanding of the role of near work and light exposure in myopia onset and progression.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Weizhong Lan for generously providing the Clouclip devices. The study was funded by NIH P30 EY007551.

References

- 1.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016; 123: 1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flitcroft DI. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Prog Retin Eye Res 2012; 31: 622–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tideman JW, Snabel MC, Tedja MS et al. Association of axial length with risk of uncorrectable visual impairment for Europeans with myopia. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016; 134: 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saw SM, Gazzard G, Shih-Yen EC et al. Myopia and associated pathological complications. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2005; 25: 381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fricke TR, Holden BA, Wilson DA et al. Global cost of correcting vision impairment from uncorrected refractive error. Bull World Health Organ 2012; 90: 728–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose K, Harper R, Tromans C et al. Quality of life in myopia. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84: 1031–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutti DO. Hereditary and environmental contributions to emmetropization and myopia. Optom Vis Sci 2010; 87: 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah RL, Huang Y, Guggenheim JA et al. Time outdoors at specific ages during early childhood and the risk of incident myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017; 58: 1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dirani M, Tong L, Gazzard G et al. Outdoor activity and myopia in Singapore teenage children. Br J Ophthalmol 2009; 93: 997–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashby R, Ohlendorf A, Schaeffel F. The effect of ambient illuminance on the development of deprivation myopia in chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009; 50: 5348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dharani R, Lee CF, Theng ZX et al. Comparison of measurements of time outdoors and light levels as risk factors for myopia in young Singapore children. Eye 2012; 26: 911–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saw S-M, Hong C-Y, Chia K-S et al. Nearwork and myopia in young children. The Lancet 2001; 357: 390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You X, Wang L, Tan H et al. Near work related behaviors associated with myopic shifts among primary school students in the Jiading District of Shanghai: A school-based one-year cohort study. Plos One 2016; 11: e0154671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ip JM, Saw SM, Rose KA et al. Role of near work in myopia: findings in a sample of Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49: 2903–2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoogerheide J, Rempt F, Hoogenboom WP. Acquired myopia in young pilots. Ophthalmologica 1971; 163: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charman WN, Radhakrishnan H. Peripheral refraction and the development of refractive error: a review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2010; 30: 321–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lingham G, Yazar S, Lucas RM et al. Time spent outdoors in childhood is associated with reduced risk of myopia as an adult. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 6337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French AN, Ashby RS, Morgan IG et al. Time outdoors and the prevention of myopia. Exp Eye Res 2013; 114: 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Ip J et al. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 1279–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suhr Thykjaer A, Lundberg K, Grauslund J. Physical activity in relation to development and progression of myopia - a systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol 2017; 95: 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundberg K, Suhr Thykjaer A, Søgaard Hansen R et al. Physical activity and myopia in Danish children-The CHAMPS Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol 2018; 96: 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwiazda J, Deng L, Manny R et al. Seasonal variations in the progression of myopia in children enrolled in the correction of myopia evaluation trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014; 55: 752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.French AN, Morgan IG, Mitchell P et al. Risk factors for incident myopia in Australian schoolchildren: The Sydney Adolescent Vascular and Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2013; 120: 2100–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinge B, Midelfart A, Jacobsen G et al. The influence of near-work on development of myopia among university students. A three-year longitudinal study among engineering students in Norway. Acta Ophthalmol 2000; 78: 26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi KY, Mok AY, Do CW et al. The diversified defocus profile of the near-work environment and myopia development. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2020; 40: 463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saw S-M, Shankar A, Tan S-B et al. A cohort study of incident myopia in Singaporean children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47: 1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones LA, Sinnott LT, Mutti DO et al. Parental history of myopia, sports and outdoor activities, and future myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin Z, Vasudevan B, Jhanji V et al. Near work, outdoor activity, and their association with refractive error. Optom Vis Sci 2014; 91: 376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whiteman D, Green A. Wherein lies the truth? Assessment of agreement between parent proxy and child respondents. Int J Epidemiol 1997; 26: 855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Najman JM, Williams GM, Nikles J et al. Bias influencing maternal reports of child behaviour and emotional state. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001; 36: 186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nickels S, Hopf S, Pfeiffer N et al. Myopia is associated with education: Results from NHANES 1999–2008. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0211196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saw SM, Carkeet A, Chia KS et al. Component dependent risk factors for ocular parameters in Singapore Chinese children. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 2065–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gwiazda J, Deng L, Dias L et al. Association of education and occupation with myopia in COMET parents. Optom Vis Sci 2011; 88: 1045–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.You QS, Wu LJ, Duan JL et al. Factors associated with myopia in school children in China: The Beijing Childhood Eye Study. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e52668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ip JM, Rose KA, Morgan IG et al. Myopia and the urban environment: findings in a sample of 12-year-old Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49: 3858–3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li SM, Li SY, Kang MT et al. Near work related parameters and myopia in Chinese children: The anyang childhood eye study. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0134514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanca C, Saw SM. The association between digital screen time and myopia: A systematic review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2020; 40: 216–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu S, Ye S, Xi W et al. Electronic devices and myopic refraction among children aged 6–14 years in urban areas of Tianjin, China. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2019; 39: 282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harmon DB. Notes on a Dyanamic Theory of Vision. Austin TX, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen L, Lan W, Huang Y et al. A novel device to record the behavior related to myopia development-preliminary results in the lab. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016; 57: 2491. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao Y, Lan W, Wen L et al. An effectiveness study of a wearable device (Clouclip) intervention in unhealthy visual behaviors among school-age children. Medicine 2020; 99: e17992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhandari KR, Ostrin LA. Validation of the Clouclip and utility in measuring viewing distance in adults. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2020; 40: 801–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams R, Bakshi S, Ostrin EJ et al. Continuous objective assessment of near work. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 6901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen L, Cheng Q, Cao Y et al. The Clouclip, a wearable device for measuring near-work and outdoor time: validation and comparison of objective measures with questionnaire estimates. Acta Ophthalmol 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen L, Cheng Q, Lan W et al. An objective comparison of light intensity and near-visual tasks between rural and urban school children in China by a wearable device Clouclip. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2019; 8: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wen L, Cao Y, Cheng Q et al. Objectively measured near work, outdoor exposure and myopia in children. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:1542–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith EL 3rd, Hung, Kee CS et al. Effects of brief periods of unrestricted vision on the development of form-deprivation myopia in monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002; 43: 291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Napper GA, Brennan NA, Barrington M et al. The effect of an interrupted daily period of normal visual stimulation on form deprivation myopia in chicks. Vision Res 1997; 37: 1557–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Norton TT, Siegwart JT, Amedo AO. Effectiveness of hyperopic defocus, minimal defocus, or myopic defocus in competition with a myopiagenic stimulus in tree shrew eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47: 4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartwig A, Gowen E, Charman WN et al. Working distance and eye and head movements during near work in myopes and non-myopes. Clin Exp Optom 2011; 94: 536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wing Leung T, Flitcroft DI, Wallman J et al. A novel instrument for logging nearwork distance. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2011; 31: 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Bao J, Ou L et al. Reading behavior of emmetropic schoolchildren in China. Vision Res 2013; 86: 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bao J, Drobe B, Wang Y et al. Influence of near tasks on posture in myopic Chinese schoolchildren. Optom Vis Sci 2015; 92: 908–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenfield M, Wong NN, Solan HA. Nearwork distances in children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2001; 21: 75–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charman WN. Near vision, lags of accommodation and myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 1999; 19: 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gwiazda J, Thorn F, Held R. Accommodation, accommodative convergence, and response AC/A ratios before and at the onset of myopia in children. Optom Vis Sci 2005; 82: 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harb E, Thorn F, Troilo D. Characteristics of accommodative behavior during sustained reading in emmetropes and myopes. Vision Res 2006; 46: 2581–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]