Abstract

Exposure to respirable air particulate matter (PM2.5) in ambient air is associated with morbidity and premature deaths. A major source of PM2.5 is the photooxidation of volatile plant-produced organic compounds such as isoprene. Photochemical oxidation of isoprene leads to the formation of hydroperoxides, environmental oxidants that lead to inflammatory (IL-8) and adaptive (HMOX1) gene expression in human airway epithelial cells (HAEC). To examine the mechanism through which these oxidants alter intracellular redox balance, we used live-cell imaging to monitor the effects of isoprene hydroxyhydroperoxides (ISOPOOH) in HAEC expressing roGFP2, a sensor of the glutathione redox potential (EGSH). Non-cytotoxic exposure of HAEC to ISOPOOH resulted in a rapid and robust increase in EGSH that was independent of the generation of intracellular or extracellular hydrogen peroxide. Our results point to oxidation of GSH through the redox relay initiated by glutathione peroxidase 4, directly by ISOPOOH or indirectly by ISOPOOH-generated lipid hydroperoxides. We did not find evidence for involvement of peroxiredoxin 6. Supplementation of HAEC with polyunsaturated fatty acids enhanced ISOPOOH-induced glutathione oxidation, providing additional evidence that ISOPOOH initiates lipid peroxidation of cellular membranes. These findings demonstrate that ISOPOOH is a potent environmental airborne hydroperoxide with the potential to contribute to oxidative burden of human airway posed by inhalation of secondary organic aerosols.

Keywords: Air pollution, Secondary organic aerosols, Oxidative stress, Glutathione redox potential, Lipid peroxidation, Live cell imagining

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

ISOPOOH exposure of HAEC increases EGSH monitored by live cell imaging.

-

•

Effect of ISOPOOH on EGSH does not involve intracellular or extracellular H2O2.

-

•

Knockdown of GPX4 in HAEC significantly diminished ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation.

-

•

ISOPOOH exposure of cellular and biomimetic membranes resulted in lipid peroxidation.

-

•

PUFA supplementation increased HAEC sensitivity to ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation.

Abbreviations

- Adenoviral Overexpression of Intracellular Catalase

AdCAT

- Airborne Fine Particulate Matter

PM2.5

- Dithiothreitol

DTT

- Docosahexaenoic Acid

DHA

- Eicosapentaenoic Acid

EPA

- Giant Unilamellar Vesicles

GUVs

- Glutaredoxin

GRX

- Glutathione Peroxidases

GPX

- Glutathione Redox Potential

EGSH

- Glutathione Reductase

GR

- Human Airway Epithelial Cells

HAEC

- Isoprene-derived Secondary Organic Aerosols

Iso-SOA

- Isoprene Hydroxyhydroperoxide

ISOPOOH

- Oxidized Glutathione

GSSG

- Palmitic Acid

PA

- Peroxiredoxin

PRX

- Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

PUFAs

- Redox Green Fluorescent Protein

roGFP

- Reduced Glutathione

GSH

- Secondary Organic Aerosols

SOA

- tert-butyl hydroperoxide

t-BOOH

- Total Lipid Extracts

TLE

1. Introduction

Environmental peroxides produced by photochemical oxidation of biogenic volatile organic compounds such as isoprene contributes to the formation of secondary organic aerosols (SOA). SOA are the largest mass fraction of ambient particulate matter (PM2.5), a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]. While much of the interest in isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosols (Iso-SOA) concerns the mass contribution to PM2.5, recent studies have demonstrated adverse biological effects from direct human exposure to Iso-SOA [9].

Exposure of human airway epithelial cells (HAEC) to Iso-SOA induces inflammatory and adaptive gene expression that is regulated by oxidant responsive signaling [10]. This mechanism is supported by Lin et al. [11], who reported activation of the KEAP1/Nrf-2/ARE signaling pathway in HAEC exposed to Iso-SOA. Consistent with this observation, Iso-SOA has been shown to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in HAEC [10].

The mixture of isoprene-derived compounds present in Iso-SOA includes environmental hydroperoxides such as isoprene hydroxyhydroperoxide (ISOPOOH) and electrophilic compounds. The mechanisms through which environmental hydroperoxides such as ISOPOOH induce oxidant stress in exposed cells have not been established; specifically, it is presently unknown whether these compounds act directly on HAEC or through the generation of intermediate oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide or lipid hydroperoxides formed intra- or extracellularly. Peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids can disrupt membrane structure and result in downstream production of oxidized products [12,13], and in accordance with expectations, increasing the membrane unsaturated fatty acid content in HAEC has been shown to increase sensitivity to oxidant stress [12,14].

The high temporal resolution provided by live-cell imaging is well suited to the study of transient events such as those induced by oxidative stress [15]. We have shown that monitoring the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (EGSH) using the genetically-encoded sensor roGFP [16] provides a dynamic index of intracellular redox changes that occur in response to xenobiotic oxidative stress induced by exposure of HAEC to Zn [17], ozone [18], quinones [19], and lipid hydroperoxides [20]. In addition to its utility as a real-time reporter of intracellular EGSH, live-cell imaging using roGFP is an experimental approach that has been used extensively to probe biochemical processes, such as bioenergetic adaptations, involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics and to identify enzymatic activities that mediate them [16,21,22]. While the redox relay through which roGFP equilibrates with EGSH was originally described for H2O2, we recently showed that the lipid hydroperoxide 9-HpODE can also initiate glutathione oxidation through glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) that is reported by roGFP [20]. Glutathione-S-transferase-mediated glutathionylation of peroxiredoxin 6 (PRX6), a 1-cysteine lipid hydroperoxide scavenging enzyme [23], is a second potential mechanism for oxidation of glutathione that may be sensed by roGFP.

In the present study we elucidate the mechanism through which exposure to the environmental hydroperoxide ISOPOOH induces oxidative stress in cultured HAEC. We report that ISOPOOH potentiates lipid peroxidation leading to the oxidation of glutathione.

2. Methods

2.1. Material and reagents

All media for cell culture including: minimum essential media with glutamax (MEM), Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco, and Bovine type 1 collagen was obtained from Fisher Scientific, Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Willco Wells black glass-bottom dishes were used for confocal microscopy (Amsterdam, Netherlands). Laboratory regents and chemicals including: hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH), dithiothreitol (DTT), hexadimethrine bromide (Polybrene), 2-acetylamino-3-[4-(2-acetylamino-2-carboxyethylsulfanylthiocarbonylamino)phenylthiocarbamoylsulfanyl] propionic acid (2-AAPA), sodium selenite, D-(+)-glucose, extracellular catalase from bovine liver, human fibronectin, and fatty acid free fraction V bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Liperfluo was obtained from Dojindo (Rockville, MD, USA). Calcein AM was purchased from Invitrogen- Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Basic laboratory supplies were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Fatty acids: palmitic acid (PA) and oleic acid (OA), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs): eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). 1-stearoyl-2-docosahexaenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (SDPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PAPC), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Birmingham, AL). All solvents were HPLC grade and purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Indium tin oxide (ITO) coated glass slides were purchased from Sigma (Burlington, MA). Fresh stocks of lipid mixtures were used to minimize oxidation, and handling of lipids occurred under low light conditions and a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. Antibodies for GPX4 and PRX6 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA).

2.2. Synthesis of ISOPOOH

Aqueous hydrogen peroxide (30%; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was extracted three times with ethyl ether and the extracts combined and dried over MgSO4. KMnO4 titration determined this solution to be ∼1 M [24]. To 20 mL of this solution was added 1 g 2-methyl-2-vinyloxirane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 2–3 mg phosphomolybdic acid hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) catalyst [25]. The mixture was stirred at room temperature and monitored by 1H NMR until the starting material was consumed. The solvent was removed under vacuum on a rotary evaporator at room temperature and the residue frozen and lyophilized for a ∼2 h to remove the bulk of the hydrogen peroxide. The lyophilizate was then purified by column chromatography on silica gel using a solvent gradient from 50% ether in hexane to 100% ether. The factions were analyzed by 1H NMR and fractions that were free of residual H2O2 were used for exposure experiments.

2.3. Cell culture

SV-40 transformed human bronchial epithelial cell line 16HBE14 (16-HBE) was gifted from the laboratory of Dr. Ilona Jaspers (UNC Chapel Hill, NC, USA) [26]. 16-HBE cells were cultured with complete media: MEM with Glutamax with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All containers used to culture 16-HBE cells were coated with a matrix of: 30 μg/mL bovine type 1 collagen, 0.01% BSA, and 1% human fibronectin in LHC Basal Medium. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified environment containing 5% carbon dioxide (CO2). For live-cell imaging, cells were cultured in 35 mm black glass-bottom dishes with 12 mm #1.5 glass aperture.

2.4. Genetically encoded constructs

The plasmids for the genetically encoded roGFP2 were a generous gift from S.J. Remington (University of Oregon, OR, USA). The plasmid for genetically encoded glutaredoxin-linked roGFP (GRX1-roGFP2) was a generous gift from Professor Doctor Tobias Dick (German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany). The plasmid for the genetically encoded HyPer was purchased from Evrogen (Farmingdale, NY, USA). The adenoviral vector for the overexpression of intracellular catalase (AdCAT) was purchased from the University of Iowa Viral Vector Core (Iowa City, IA, USA).

2.5. shRNA design

ShRNA hairpin oligonucleotides shown below were designed by selecting an 18-bp site from the human GPX4 complete mRNA (NCBI Accession: NM_002085.4) and human PRX6 complete mRNA (NCBI Accession: NM_004905.3) optimized for siRNA targeting of GPX4 and PRX6 mRNAs, or a random 18-bp sequence (scramble) with no predicted homology to human genomic or transcript sequences.:

GPX4: 5′- GATCTTGCTGAACATATC -3′

PRX6: 5′- CTTCTTCTTCAGGGATGG -3′

Scramble: 5′- ACTCTCGCCCAAGCGAGA -3′

Single stranded synthetic 97-bp oligonucleotides (Invitrogen Corp., Valcencia, CA) incorporating sense/antisense sequences in a stem-loop motif were PCR amplified using the primers forward: 5′-AGTCACTCGAGTGCTGTTGACAGTGAG-3′ and reverse: 5′-AAGTCAGGATCCTCCGAGGCAGTAGG-3.’ The resulting PCR products were subcloned into a modified lentiviral transfer vector, pRIPZ (Dharmacon, Birmingham, AL) between XhoI and BamHI restriction sites. The resulting shRNA expression constructs were verified by fluorescent DNA capillary sequencing. This cloning strategy nests the shRNA fragments between 5′ and 3′ miRNA30 adaptors within the 3′ untranslated region of a polycistronic red fluorescent protein reporter gene under the control of a CMV promoter.

2.6. Lentiviral vector production and titering

HEK293T cells were co-transfected in 10 cm dishes with purified transfer vector plasmids and lentiviral packing mix (Dharmacon; Birmingham, AL) according to manufacturer's instructions. 16 h post-transfection, cell culture medium was replaced with fresh DMEM and cells were incubated for an additional 48 h at 37 °C. Medium was then harvested and detached cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 5000×g. The resulting supernatants from the individual transfections were concentrated once by low-speed centrifugation through an Amicon Ultra 100kD centrifuge filter unit (Millipore; Billerica, MA), and the retentates were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. To determine viral titers, 2 × 104 HEK293T cells were transduced with 50 μl of lentiviral stock dilutions ranging from 1:10 to 1:781,250. Viral titers (expressed as transducing units per ml viral stock) were determined 96 h post-transduction by counting fluorescent cell colonies by fluorescent microscopy and multiplying the colony count by the dilution and volume factors.

2.7. Viral transduction

Stable cellular expression of genetically encoded fluorescent reporters was achieved through a lentiviral transduction of 16-HBE cells. 16-HBE cells were seeded in a 6-well plate overnight to reach 40% confluency. 16-HBE cells were then serum-starved in LHC Basal Medium for 2 h. Lentivirus encoding either roGFP2, GRX-roGFP2, or HyPer at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 were mixed with 10 μg/mL hexadimethrine bromide (Polybrene) and incubated with 16-HBE cells for 4 h. The plate was rocked every 30 min to allow for redistribution of viral particles. After 4 h, 2 mL of complete cell culture media was added to each well, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C/5% CO2 for another 4 h. Following this incubation, media was aspirated and 16-HBE cells were washed twice with 1X DPBS. Complete cell culture media was added to each well and cells were incubated at 37 °C/5% CO2 and expanded.

Stable expression of GPX4 and PRX6 knockdown followed identical protocols using roGFP2 expressing 16-HBE cells. Cells expressing shRNAs were only used for 2 weeks before repeating the transduction. Transient overexpression of intracellular catalase was achieved using adenoviral transduction (AdCAT). AdCAT particles were mixed with LHC Basal Medium at MOI of 200 and added to cells for 4 h. Complete media (1 mL) was added and cells were incubated an additional 4 h. Cells were then washed with DPBS and fresh complete media was added until experiments the following day at confluency of 80%. All AdCAT experiments were conducted in glucose sufficient conditions (Kirkman, 1984).

2.8. Exposure conditions

All exposures were conducted on native 16-HBE cells or 16-HBE cells expressing the aforementioned genetically encoded fluorescent reporters at 80% confluency. 16-HBE cells cultured in glass bottom dishes for microscopy experiments were identically equilibrated for 30 min in Locke's Buffer, a minimal buffered salt solution which contains no organic compounds, prior to imaging [18,27]. HAEC were exposed to a variety of hydroperoxides on a custom-built microscopy stage top, maintaining 37 °C with 5% CO2 and ≥95% relative humidity at a flow rate of 3.0 L/min.

To induce overexpression of GPX, roGFP-HAEC were pre-treated for 36 h with 1 μM sodium selenite dissolved in water and diluted in complete media. To inhibit GRX, roGFP-HAEC were pretreated for 3 h with 100 μM of the small molecule inhibitor 2-AAPA, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted to less than 1% DMSO in complete media, prior to equilibration in Locke's Buffer. Exogenous catalase was suspended in 1X DPBS and was administered to roGFP-HAEC at a final concentration of 100 units/mL. In some experiments, roGFP-HAEC were deprived of glucose for 2 h to sensitize cells to oxidant exposure.

Each experiment consisted of four distinct intervals: (a) an untreated baseline for 5 min, (b) exposure to hydroperoxide for 25–35 min, (c) exposure to 1 mM H2O2 for 5 min as a maximal control to check the integrity of the roGFP relay, and (d) exposure to 5 mM DTT for 5 min to reduce sensor back to baseline. All experiments involved treatment with paired controls within 1 h of exposure.

2.9. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by Calcein AM. 16-HBE cells grown in black Willco wells microscopy dishes were washed twice with 1X DPBS. Cells were incubated with 1 μM Calcein AM in 1X DPBS for 30 min at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After incubation, cells were washed twice with 1X DPBS and replenished with Locke's Buffer. Cells were exposed to either 100 μM t-BOOH, 100 μM ISOPOOH, or 100 μM H2O2 for 35 min. Cells were then exposed to 0.1% Triton-X as a positive control. Calcein AM incorporation was assessed using 488 nm excitation and measuring 525/30 nm emission. The fluorescent intensity data are presented after normalization to baseline for each condition.

2.10. Lipid extract preparation

Total lipid extracts (TLE) were prepared from 16-HBE cells using a modified Bligh and Dyer extraction [28]. 16-HBE cells were exposed to either 100 μM ISOPOOH, 100 μM t-BOOH, 100 μM H2O2, or 1 mM H2O2 for 40 min. TLE from exposed cells were dried under a stream of nitrogen until a lipid film was formed void of excess solvent. TLE were resuspended in 1X DPBS with 0.025% BSA by vortexing for 2 min. Naïve roGFP-HAEC were then exposed to aqueous TLE.

2.11. Supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)

HAEC were supplemented with PUFA as previously described using a protocol shown to be effective in shifting the fatty acid profile with supplemented fatty acids [12]. Briefly, PUFAs were prepared in serum-free MEM with 2.5 mg/mL fatty acid-free BSA (fraction V). roGFP-HAEC were supplemented with either PA, EPA, or DHA at a final concentration of 30 μM in complete media for 16–18 h [29]. Cells were washed with 2.5 mg/mL BSA in DPBS followed by a second rinse in the appropriate exposure medium. Uptake and incorporation of PUFAs was previously confirmed with complete fatty acid profile analysis conducted via gas chromatography (Omegaquant, Sioux Falls, SD, USA) [12].

2.12. Construction of giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs)

GUVs were constructed by electroformation as described [[30], [31], [32]]. Lipids (33.3 mol% SDPC, 33.3 mol% PAPC, 33.3 mol% DOPE) and the fluorescent probe Liperfluo (0.1 mol%; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Rockville, MD) were co-dissolved in chloroform to achieve a total concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Next, 10 μg of total lipid was spread onto the conductive side of an ITO-coated glass slide. The lipid-coated slide was subjected to vacuum pumping in the dark for 1 h to remove excess solvent. Once the lipid film was dried, a GUV electroformation chamber was assembled as described [31].

GUV electroformation was performed at room temperature, in the dark, using a 250 mM sucrose solution. GUV electroformation frequency and peak-to-peak voltage was controlled using a HP3324A programmable function generator. Initially, a sine waveform with a frequency of 10 Hz and a peak-to-peak voltage ranging from 0.2 V to 1.4 V was applied and linearly increased over a 30-min period. Next, a sine waveform with a frequency of 10 Hz and a peak-to-peak voltage of 1.4 V was applied and held constant for 120 min. For the detachment of GUVs, a square waveform with a frequency of 4.5 Hz and peak-to-peak voltage of 2.1 V was applied and held constant for 30 min. Once electroformation was completed, GUVs were extracted from the chamber using a 20½-gauge needle and allowed to settle in the dark at room temperature for 30 min prior to preparing microscopy slides. GUVs were then drawn into a rectangular micro-capillary tube, mounted on a microscope slide, and the ends were sealed with nail polish. Imaging was performed at room temperature. For treated GUVs, an aliquot of GUVs was removed and treated with a final concentration of either 100 μM H2O2, ISOPOOH, t-BOOH immediately prior to preparing microscope slides for imaging.

2.13. Live-cell imaging analysis

All live-cell imaging was conducted on the Nikon Eclipse C1si spectral confocal imaging system using 404 nm, 488 nm, and 561 nm primary lasers with Perfect Focus (Nikon Instruments Corporation, Melville, NY, USA). The objective used was the 1.4 NA 60 X violet-corrected, oil-immersed lens. 16-HBE cells expressing roGFP2, GRX1-roGFP2, and HyPer monitored in time-series experiments with temporal resolution of 1 acquisition/minute or 10 acquisitions/minute were excited sequentially at 488 nm and 405 nm and emission was monitored using a 525/30 nm band-pass filter (Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT, USA). Laser power and pixel dwell time were constant for all experiments, and detector gain was optimized prior to the start for each experiment and kept constant for the duration of the experiment.

Regions of interests (ROI) were drawn for 10 individual cells within a single well and monitored for the duration of the experiment. Data obtained from each experiment were calculated as ratios of the emission intensities at 510 nm for laser excitation at 488 nm and 405 nm. Ratios were calculated for each cell observed and normalized to the baseline and maximal response for each individual cell. The maximal response was achieved by administering 1 mM H2O2, as a control near the end of the experiment. The normalized ratios for individual ROIs (cells) were averaged to compile as one sample. The results presented in each graph are the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments.

2.14. Lipid peroxidation measurements

Lipid peroxidation of the plasma membrane in living 16-HBE cells was measured using the fluorescent sensor Liperfluo [33]. 16-HBE cells were incubated with 1 μM solution of Liperfluo in LHC Basal Medium for 30 min at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After incubation, cells were washed twice with HBSS and replenished with Locke Buffer. Cells were exposed to either 100 μM t-BOOH, 100 μM ISOPOOH, or 100 μM H2O2 for 35 min. Data was collected by exciting the sensor with 488 nm while measuring at 525/30 nm emission. The fluorescent intensities are presented after normalization to baseline for each condition.

2.15. Confocal microscopy and image analysis of GUVs

Imaging was conducted using a Nikon A1R-HD25 Confocal Microscope using a 60 × 1.49 NA APO TIRF oil immersion objective (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Secondary analysis of GUVs was conducted with NIH ImageJ. After background subtraction, the total fluorescence intensity of individual GUVs was measured by analyzing the integrated density of each GUV membrane. A circle surrounding the perimeter of each GUV membrane was first measured and then subtracted from measurement of a circle drawn around the interior of each GUV membrane. The total fluorescence intensity of each GUV membrane was normalized to its diameter to account for any disparities in GUV size.

2.16. Statistical analysis

All microscopy images were quantified using the NIS-Elements AR software (Nikon Instruments Corporation, Melville, NY, USA). All data in the main text were normalized to individual cell baseline and expressed as mean ± SEM of three or more independent experiments. All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad PRISM 9.1 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). A Two-way ANOVA analysis with post-hoc Sidak's multiple comparisons test to control were conducted for time-series experiments with two treatment groups. A threshold of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For GUV analysis, images were quantified using ImageJ FIJI [34]. A one-way ANOVA analysis with Dunnett's multiple comparison to control (untreated GUVs) was conducted for all GUV measurements. All statistical analyses were conducted in Graphpad PRISM 9.1 (Graphphad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. ISOPOOH induced glutathione oxidization in HAEC

To examine oxidative stress induced in the human airway epithelium by exposure to the environmental peroxide ISOPOOH, we used live cell imaging to monitor the oxidation state of the intracellular glutathione pool in HAEC expressing roGFP (roGFP-HAEC) exposed to ISOPOOH in real time. The exposure of HAEC to 100 μM ISOPOOH resulted in a rapid increase in EGSH, followed by a slow decline suggesting an adaptive recovery (Fig. 1A, S2A, S2B). ISOPOOH-exposed HAEC remained responsive to further oxidation with 1 mM H2O2 (positive oxidant control) and reduction by 5 mM DTT (reducing control) (Fig. 1A, S2A, S2B). Similarly, in experiments using temporal resolution ten-fold greater in magnitude (measurements taken every 6 s) responses of HAEC exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH were identical to the response shown in Fig. 1A (data not shown). Preliminary, experiments showed that 100 μM ISOPOOH was the lowest dose that produced robust effects (Fig. 1A, S2A, S2B) without inducing cytotoxicity in the study interval (Fig. 1B, S3B). 100 μM ISOPOOH showed approximately equimolar potency to known strong oxidants such as 100 μM t-BOOH and 100 μM H2O2 (Fig. S3A).

Fig. 1.

Exposure to ISOPOOH induces a rapid increase in EGSHin HAEC. A) Exposure of roGFP-HAEC to 100 μM ISOPOOH for 40 min followed by the addition of 1 mM H2O2 and 5 mM DTT. (B) Cytotoxicity of 100 μM ISOPOOH was measured in HAEC prelabeled with Calcein AM. Cells were treated with to 0.1% Triton-X at 40 min as a positive control. Data shown represent the fluorescence intensity at 510 nm resulting from sequential excitation with 488 and 405 nm laser light. Calculated ratios are corrected for baseline ratio and expressed as percent of the maximal response observed. Values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

3.2. Testing the integrity of the roGFP redox relay in HAEC exposed to ISOPOOH

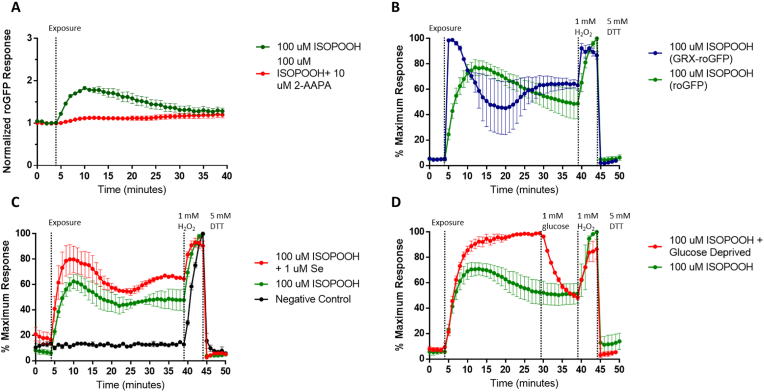

The fluorogenic sensor roGFP equilibrates with the GSH/GSSG redox pair through the activity of glutaredoxin (GRX) [16]. To examine the possibility that ISOPOOH interacts directly with the roGFP sensor, we tested the dependence of the roGFP response to ISOPOOH on GRX activity by pretreating roGFP-HAEC with 100 μM 2-AAPA, a small molecule inhibitor of GRX. As shown in Fig. 2A, pretreatment with 2-AAPA ablated the roGFP response to 100 μM ISOPOOH. While 2-AAPA is also a known inhibitor of glutathione reductase (GR), the enzyme that reduces GSSG to GSH using NADPH (Fig. S1), we observed no changes in the EGSH baseline in 2-AAPA treated cells, suggesting that any effect on GR was not sufficient to alter the kinetics of the response to ISOPOOH. Similarly, pretreating roGFP-HAEC with 100 μM 2-AAPA ablated responses to 100 μM H2O2 and t-BOOH (Figs. S4A and S5A). Furthermore, to assess the involvement of GRX in ISOPOOH-induced EGSH, we also treated HAEC expressing GRX-roGFP to ISOPOOH. Chimerically linking GRX to roGFP effectively increases the local concentration of GRX in proximity to roGFP, producing a response with higher sensitivity to GSH oxidation and faster kinetics [16]. In HAEC expressing GRX-roGFP, exposure to 100 μM ISOPOOH induced an earlier response that reached a higher plateau compared to the response in HAEC expressing roGFP (Fig. 2B). These results show that GRX is required for the ISOPOOH-induced roGFP response, ruling out direct oxidation of roGFP by ISOPOOH. GRX involvement was also validated for H2O2 and t-BOOH exposures in HAEC expressing GRX-roGFP.

Fig. 2.

ISOPOOH induces GSH oxidation through a redox relay as reported by roGFP. (A) roGFP-HAEC were treated with a GRX inhibitor 2-AAPA or vehicle for 3 h prior to exposure to 100 μM ISOPOOH at the indicated time. (B) A comparison of 16-HBEs cells expressing roGFP or GRX-roGFP exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH at the indicated time. (C) roGFP-HAEC were supplemented 1 μM sodium selenite or vehicle for 36 h prior to exposure to 100 μM ISOPOOH. (D) roGFP-HAEC were deprived of glucose for 2 h prior to exposure to 100 μM ISOPOOH followed by the addition of glucose (1 mM final). All fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline and/or maximal sensor response. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

We have previously shown in HAEC that GPX proteins mediate the oxidation of GSH by H2O2 as well as by short-chain hydroperoxides such as t-BOOH and long-chain hydroperoxides such as 9-HpODE (Figs. S4C and S5C) [20]. To determine whether the EGSH oxidation reported by roGFP reflects direct oxidation of GSH by ISOPOOH, we examined the involvement of GPX in mediating GSH-dependent reduction of ISOPOOH by increasing the expression of GPX. roGFP-HAEC were pre-treated with 1 μM sodium selenite for 36 h prior to ISOPOOH exposure [20]. As shown in Fig. 2C, roGFP-HAEC supplemented with Se evinced an accelerated rate of GSH oxidation when exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH compared to non-supplemented HAEC, consistent with a rate-limiting role of GPX4 in mediating GSH oxidation in response to ISOPOOH treatment of HAEC. Combined with the GRX findings, these data demonstrate that ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation is reported by roGFP through the same oxidative relay previously established for H2O2 (Fig. S1).

The pentose phosphate pathway utilizes glucose to produce NADPH required for GR to mount a reductive tone to oppose oxidative stress [21]. We next tested the integrity of the NADPH-dependent reductive step in the relay by depriving HAEC of glucose prior to exposure to ISOPOOH. As shown in Fig. 2D, in HAEC that were deprived of glucose for 2 h, ISOPOOH treatment produced an roGFP-reported response that was markedly potentiated in magnitude relative to cells incubated in normal glucose levels. The reintroduction of glucose caused a rapid and robust reversal of the ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation reported by roGFP in HAEC (Fig. 2D). These findings are consistent with a role for NADPH in the maintenance of EGSH in HAEC exposed to ISOPOOH. Similarly, glucose deprivation of roGFP-HAEC exposed to 100 μM H2O2 or t-BOOH also demonstrated increased sensitivity, with a similar reversal with the introduction of glucose (Figs. S4D and S5D). Taken together with the findings showing GPX involvement in ISOPOOH-induced oxidation of GSH, and the requirement of GRX in the transduction of EGSH to roGFP, these data validated the use of roGFP as a reporter of the oxidation state of the GSH in HAEC exposed to ISOPOOH.

3.3. ISOPOOH induced GSH oxidization is not dependent on the generation of H2O2

Organic hydroperoxides are unstable compounds that can decay in aqueous media [35]. We therefore next investigated the possibility that ISOPOOH-induced oxidation of GSH is mediated by the generation of secondary oxidants, specifically H2O2. To determine whether the increase of EGSH induced by ISOPOOH in roGFP-HAEC is mediated by the generation of extracellular H2O2, we used exogenous catalase to specifically scavenge H2O2 that might be produced in the medium. As shown in Fig. 3A, the presence of 100 units/mL of bovine liver catalase effectively ablated GSH-oxidation induced by 100 μM H2O2. In marked contrast, the same concentration of exogenous catalase failed to suppress glutathione oxidation induced by exposure of HAEC to 100 μM ISOPOOH (Fig. 3B), and indeed, appeared to cause a time-dependent enhancement in response to ISOPOOH. Paradoxically, the effect of ISOPOOH appeared to be enhanced by the presence of 100 units/mL of extracellular catalase, suggesting possible oxidant generation by redox cycling between the peroxide and the iron in the catalytic center in catalase; however, use of catalase inactivated by pretreatment with an equimolar concentration of the iron-chelator deferoxamine did not alter the EGSH response in HAEC exposed to ISOPOOH compared to untreated catalase (data not shown), arguing against a redox-cycling event. We speculate that the enhanced activity could be the result of the formation of alkoxy radicals from some homolytic cleavage of ISOPOOH by catalase [36].

Fig. 3.

GSH oxidation induced by ISOPOOH is independent of extracellular H2O2. (A) roGFP-HAEC were exposed to 100 μM H2O2 in the presence of 100 units/mL of extracellular catalase or vehicle alone. (B) roGFP-HAEC exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH in the presence of 100 units/mL of extracellular catalase or vehicle alone. All fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline and maximal sensor response. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

We next examined whether ISOPOOH-induced oxidation of GSH is dependent on intracellular generation of H2O2. While adenoviral overexpression of catalase in roGFP-HAEC ablated roGFP responses to H2O2 at concentrations up to 1 mM (Fig. 4A), catalase had no effect on ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation in roGFP-HAEC, which showed time dependent increase similar to that observed with exogenous catalase (Fig. 4B). Similarly, extracellular catalase and overexpression of intracellular catalase failed to dampen t-BOOH-induced GSH oxidation in HAEC (Fig. S6).

Fig. 4.

GSH oxidation by ISOPOOH is independent of intracellular H2O2. (A) roGFP-HAEC overexpressing intracellular catalase were exposed to 100 μM H2O2 or vehicle alone. (B) roGFP-HAEC overexpressing intracellular catalase were exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH or vehicle alone. (C) HAEC expressing the sensor HyPer were exposed to 100 μM H2O2 or vehicle alone. (D) HAEC expressing the sensor HyPer were exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH or vehicle alone. All fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline and maximal sensor response. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

Additionally, we measured levels of intracellular H2O2 in HAEC expressing HyPer, a specific and sensitive fluorogenic reporter of H2O2 [37]. HyPer expressing HAEC (Hyper-HAEC) exposed to ISOPOOH showed no detectable increase in intracellular concentrations of cytosolic H2O2 (Fig. 4C and D). Taken together, these data show that ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation is not dependent on the generation of extracellular or intracellular H2O2.

3.4. ISOPOOH induced EGSH oxidization is mediated through glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)

Having eliminated H2O2 as major contributor, we next assessed the role of lipid hydroperoxides as potential mediators of ISOPOOH-induced glutathione oxidation in HAEC. Although there is some overlap with other GPX forms, the GPX4 isozyme is known to be relatively specific for long chain lipid hydroperoxides [38], and we recently showed that its activity can mediate GSH oxidation induced by lipid hydroperoxides in roGFP-HAEC [20]. As expected, shRNA knockdown of GPX4 expression did not alter the H2O2-induced increase in EGSH in HAEC (Fig. 5A). However, GPX4 knockdown resulted in a significant reduction in ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation compared to a scramble shRNA control sequence (Fig. 5C). Like ISOPOOH, EGSH increases induced by t-BOOH were also significantly diminished in roGFP-GPX4 KD HAEC relative to scramble controls (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation is mediated by GPX4. HAEC expressing roGFP and GPX4 shRNA (GPX4 KD) or a scramble control were exposed to (A) 100 μM H2O2 (C) 100 μM ISOPOOH, or (E) 100 μM t-BOOH. EGSH response to (B) 100 μM H2O2 (D) 100 μM ISOPOOH, or (F) 100 μM t-BOOH expressing GPX4 knockdown were compared to roGFP-HAEC with wildtype GPX4 expression in the same cultures. All fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

The efficiency of lentiviral-targeted gene expression knockdown is known to vary among cells in a population [39]. The presence of an additional red fluorescent protein marker in the GPX4 and scramble (control) shRNA vectors permitted visual identification of roGFP-HAEC expressing GPX4 KD or scramble sequences and non-transduced roGFP-HAEC in the same microscopy field. This facilitated a direct comparison of GPX4 KD and scramble shRNA positive cells side-by-side with non-transduced roGFP-HAEC expressing normal levels of GPX4, as both respond to hydroperoxide exposure in real time. As shown in Fig. 5B, D, and 5F, the comparison of adjacent exposures of GPX4 KD to control roGFP-HAEC showed the same pattern with hydroperoxide stimulation as that seen in heterogenous cultures of GPX4 KD and scramble shRNA transduced cells (Fig. 5A, C, 5E), thus supporting the role of GPX4 in mediating ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation.

Peroxiredoxin 6 (PRX6) has a substrate specificity similar to GPX4 [40]. Since PRX6 is reduced by glutathione-S-transferase using GSH, it could potentially play a role in glutathione oxidation induced by lipid hydroperoxides formed by exposure of HAEC to ISOPOOH. The EGSH increase in roGFP-HAEC expressing a PRX6 shRNA vector showed no significant difference in response to 100 μM ISOPOOH exposure relative to cells transduced with a scramble control vector (Fig. 6A, C, 6E). Similar to the GPX4 knockdown experiments, the red fluorescent protein encoded in the PRX6 KD and scramble vectors permitted visual identification of PRX6 and scramble controls in roGFP-HAEC. Comparison of PRX6 shRNA positive cells to adjacent normal expressing PRX6 HAEC also showed no difference in responses to exposures to ISOPOOH, H2O2, or t-BOOH (Fig. 6B, D, 6F). These findings suggest that PRX6 activity is not a major contributor to metabolism of hydroperoxides that induce GSH oxidation, as a key reported by roGFP, further implicating GPX4 as the enzyme responsible for ISOPOOH activity.

Fig. 6.

ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation is not mediated by PRX6. HAEC expressing roGFP and PRX6 shRNA (PRX6 KD) or a scramble control were exposed to (A) 100 μM H2O2 (C) 100 μM ISOPOOH, or (E) 100 μM t-BOOH. EGSH response to (B) 100 μM H2O2 (D) 100 μM ISOPOOH, or (F) 100 μM t-BOOH expressing PRX6 knockdown were compared to roGFP-HAEC with wildtype PRX6 expression in the same cultures. All fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

The involvement of GPX4 in GSH oxidation thus suggests the possibility that ISOPOOH exposure generates secondary lipid hydroperoxides which are capable of oxidizing GSH through the action of GPX4.

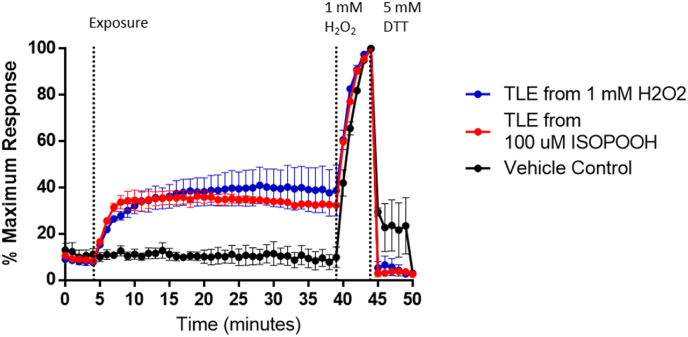

3.5. ISOPOOH induces lipid peroxidation of cellular membranes in HAEC

We next asked whether GPX4 mediates GSH oxidation induced by ISOPOOH exposure through the production of secondary lipid hydroperoxides. As an initial test of the generation of bioactive lipid hydroperoxides in HAEC treated with ISOPOOH, total lipid extracts (TLE) were prepared from HAEC exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH and were subsequently added to unexposed HAEC cultures. As shown in Fig. 7, the addition of TLE from ISOPOOH-exposed HAEC induced oxidation of GSH in naïve HAEC (Fig. 7). TLE from HAEC which had been exposed to 100 or 1000 μM H2O2 similarly increased EGSH in unexposed roGFP-HAEC (Fig. S7). Furthermore, TLE from HAEC exposed to 100 μM t-BOOH which is known to induce lipid peroxidation, showed similar increases in GSH oxidation in unexposed roGFP-HAEC (Fig. S8). Furthermore, to ensure that ISOPOOH could not have been carried over in the TLE, organic extracts of media containing ISOPOOH were taken to dryness under nitrogen and showed no effect on EGSH in HAEC (data not shown). These data are consistent with the notion that bioactive lipid products are formed in HAEC treated with ISOPOOH.

Fig. 7.

ISOPOOH exposure produces secondary organic oxidative species in HAEC. roGFP-HAEC were exposed to total lipid extracts (TLE) prepared from HAEC exposed to either 100 μM ISOPOOH, 1 mM H2O2, or 0.025% BSA (Vehicle Control) for 40 min. All fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline and maximal sensor response. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

The fluorophore Liperfluo partitions into cellular membranes to allow for lipid hydroperoxide detection and quantification. It has been demonstrated by Yamanaka et al. that changes in Liperfluo's fluorescent properties are mediated through the reduction of lipid hydroperoxides to lipid alcohols [33]. As shown in Fig. 8, exposure of Liperfluo-labelled HAEC to 100 μM ISOPOOH resulted in an increase in fluorescence intensity, indicating that ISOPOOH exposure generates lipid hydroperoxides, relative to vehicle treated control cells. Similar results were obtained in HAEC exposed to 100 μM H2O2 or t-BOOH (Fig. 8). Overall, while ISOPOOH may directly oxidize GPX4, these data suggest that GSH oxidation induced by ISOPOOH exposure of HAEC is mediated by secondary lipid hydroperoxides formed through peroxidation of cellular membranes.

Fig. 8.

ISOPOOH exposure produces secondary lipid hydroperoxides in HAEC membranes. HAEC prelabeled with the fluorophore Liperfluo were exposed to either 100 μM t-BOOH (green line), ISOPOOH (red line), H2O2 (blue line), or vehicle (black line) for 35 min after a 5-min baseline. Data shown represent the fluorescence intensity at 510 nm resulting from excitation with 488 nm laser light. All fluorescence intensity values were corrected for baseline fluorescence. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. One-sided error bars were used for clarity. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To further explore the potential formation of lipid hydroperoxides when ISOPOOH interacts with cellular membranes, we employed a biomimetic membrane system in which the fatty acid composition can be tightly controlled. Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) were constructed by electroformation of various phospholipids containing unsaturated fatty acids [(18:0–22:6)-PC/(16:0–20:4)-PC/(18:1)2PE] and visualized by the sensor Liperfluo. Liperfluo-containing GUVs exposed to 100 μM ISOPOOH showed increased fluorescence intensity as compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 9). The diameter of each GUV was also measured to eliminate any artifacts arising from variations in GUV size distribution. These data highlight the oxidative potency of ISOPOOH given that direct interaction of ISOPOOH with cellular and biomimetic membranes results in increased peroxidation of unsaturated phospholipid fatty acids.

Fig. 9.

ISPOOH induces lipid peroxidation in a cell free biomimetic membrane preparation. (A) Representative images of untreated GUVs visualized with Liperfluo (0.1 mol%) (left panel) and GUVs treated with 100 μM H2O2, ISOPOOH, and t-BOOH, respectively (right panel). GUVs were composed of (18:0–22:6) PC/(16:0–20:4) PC/(18:1)2DOPE (33.3/33.3/33.3 mol%). (B) The average fluorescence intensity of individual GUV membranes (left panel), either untreated or treated with 100 μM H2O2, ISOPOOH, and t-BOOH, respectively was determined for each individual vesicle, as well as the average GUV diameter (right panel). Data shwon are average ± SEM from a total of 150–300 vesicles analyzed from n = 2–3 independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significance from untreated vesicles: ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars are 10 μm.

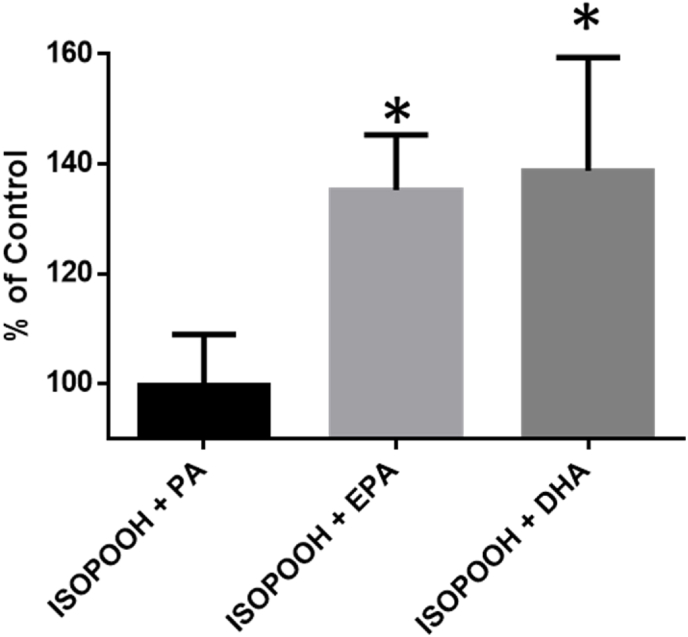

3.6. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) supplementation potentiates ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation in HAEC

The GUV experiment suggested that membrane fatty acid saturation plays a role in the potency with which ISOPOOH oxidizes GSH in HAEC. We therefore sought to determine whether modulating the PUFA content of HAEC membranes prior to exposure to ISOPOOH influences the magnitude of glutathione oxidation in HAEC. We pretreated roGFP-HAECs with BSA conjugated PA (16:0), EPA (20:5n-3), or DHA (22:6n-3) 16–18 h prior to ISOPOOH exposure. As shown in Fig. 10, ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation was markedly potentiated in HAEC pretreated with EPA or DHA relative to unsupplemented controls. HAEC pretreated with EPA or DHA before exposure to H2O2 showed similar increases in EGSH (Fig. S9). HAEC supplemented with palmitic acid, a saturated fatty acid, exposed to ISOPOOH, H2O2, or t-BOOH did not show alterations in GSH oxidation compared to supplemented controls (Fig. 10, S9, S10). These findings show that fatty acid unsaturation is a determinant of ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation as reported by roGFP in HAEC.

Fig. 10.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids increase HAEC sensitivity to ISOPOOH-induced changes in EGSH. roGFP-HAEC were supplemented with 30 μM PA, EPA, or DHA for 16–18 h prior to exposure to 100 μM ISOPOOH for 5 min. The ratio of 510 nm fluorescence intensity by 488 nm–405 nm excitation was controlled for baseline and positive control (1 mM H2O2 treatment) is shown as the percent of the response in unsupplemented controls. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. Asterisks denote significance difference from unsupplemented controls: *, p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

With estimated releases of 500 Tg/year, isoprene is the most abundant non-methane hydrocarbon in the atmosphere and is known to be a major precursor of a variety of photochemical oxidation products, including hydroperoxides [41]. We previously reported that exposure to long-chain lipid hydroperoxides, such as 9-HpODE, induces alterations in cellular metabolism and oxidative stress in HAEC [20]. However, despite their pervasiveness in the atmosphere, the initiating toxicological events arising from exposure to low-molecular weight environmental hydroperoxides remain to be investigated. In this study we present the first report on a mechanism of action through which exposure to an environmentally relevant hydroperoxide, such as ISOPOOH, initiates oxidative stress in HAEC.

Inasmuch as glutathione is present in millimolar concentrations in most cells, the glutathione redox potential is a relevant and quantifiable marker of the intracellular redox state [42]. Key proteins involved in many facets of cellular function are subject to regulation through reversible oxidation of specific cysteinyl thiols which is reflected in the EGSH [43]. The high temporal resolution of live-cell imaging using roGFP, a sensor that reports on the intracellular EGSH, is advantageous to the elucidation of the early oxidative effects of xenobiotic exposure in HAEC [15]. Using this approach, we observed that exposure of roGFP-HAEC to ISOPOOH causes a rapid and robust increase in EGSH. However, the interactions of H2O2, low molecular weight environmental organic hydroperoxides or long-chain lipid hydroperoxides with glutathione, between glutathione and roGFP, and between glutathione and NADPH, all require the participation of key enzymes arranged in a specific redox relay that includes GPX, GRX, and GR [16,21,22]. Inserting roGFP into the relay can validate its use as a readout of EGSH in HAEC exposed to ISOPOOH and provide valuable insight into the mechanism of ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation. While the redox relay through which roGFP equilibrates with EGSH is well described for H2O2, we demonstrate here by using extra and intracellular catalase interventions as well as the sensor HyPer that the effect of ISOPOOH on HAEC is not dependent on generation of extracellular or intracellular H2O2.

We then sought to determine the involvement of the glutathione peroxidases. Within the GPX family of proteins, GPX1 has strong selectivity for small inorganic peroxides such as H2O2 while GPX4 has demonstrated selectivity for long-chain lipid hydroperoxides [20,44]. shRNA knockdown of GPX4 revealed that it is a critical protein involved in regulating GSH oxidation in HAEC following ISOPOOH exposure. We also investigated the possible involvement of ISOPOOH-mediated lipid peroxidation and show evidence pointing to the participation of lipid hydroperoxides. PRX6 is another lipid hydroperoxide scavenger enzyme. In contrast to GPX4, knockdown of PRX6 had no effect on the roGFP response to ISOPOOH, indicating that PRX6 may not contribute significantly to ISOPOOH-induced oxidative stress. However, the persistence of ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation in PRX6 knockdown cells does not rule out PRX6 involvement, rather it shows that PRX6 does not have a significant role in reducing ISOPOOH-generated lipid hydroperoxides in the roGFP redox relay. Furthermore, although we show that GPX4 is a critical protein in mediating the ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation, we cannot rule out the involvement of other GPX isotypes, which remains an area for future investigation.

The demonstration that organic extracts of ISOPOOH-treated HAEC can convey the glutathione-oxidizing activity to naïve cells suggests the generation of oxidizing intermediates. Direct measurement of lipid hydroperoxides by Lipferfluo confirmed the formation of lipid hydroperoxides in HAEC following ISOPOOH exposure, as did the findings we obtained using a biomimetic membrane system.

Lastly, the involvement of lipid hydroperoxides in mediating glutathione oxidation induced by ISOPOOH is further supported by our experiments showing its potentiation in HAEC containing elevated levels of unsaturated fatty acids. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, specifically ω-3 PUFA dietary supplementation, has previously been shown to ameliorate the adverse health effects of exposure to air pollution [45,46]. However, it has also been shown that lipid peroxidation and resulting oxidative stress by strong oxidants such as ozone, can be enhanced by increasing the degree of unsaturation of fatty acids in cellular membranes [12]. We similarly show here that increasing the content of unsaturated fatty acids in HAEC membranes increases their sensitivity to ISOPOOH exposure. Furthermore, compared to H2O2 and a potent organic hydroperoxide t-BOOH, ISOPOOH demonstrated similar potency inducing lipid peroxidation and GSH oxidation in HAEC. Previous reports have implicated the production of lipid hydroperoxides in receptor-mediated activation of critical signaling pathways [47], thereby potentially linking ISOPOOH exposure to altered cell signaling.

The finding that glucose deprivation potentiates EGSH, and that glucose replacement reverses ISOPOOH-induced GSH oxidation is consistent with the requirement of NADPH for glutathione reductase activity. Oxidant exposure induces sulfenylation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [48,49]. Peroxide mediated sulfenylation of GAPDH shifts the metabolism of glucose from glycolysis to PPP [50,51]. Since, the inactivation of GAPDH is reversible, this posttranslational modification allows the cell to maintain homeostatic equilibrium by shifting between metabolic function and the redox balance via the production of NADPH [21,50]. This observation implies that the oxidative stress induced by ISOPOOH exposure may be tightly regulated by adaptative intracellular metabolic changes. Therefore, further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms that underlie ISOPOOH effects on cellular bioenergetics. Of interest is whether ISOPOOH can directly oxidize GAPDH or if GADPH is sulfenylated by ISOPOOH-generated secondary lipid hydroperoxides.

ISOPOOH is a first-generation photochemical oxidation product of isoprene. In the western United States, daytime ambient ISOPOOH concentrations have reached 1–2 ppb [52,53]. Given the ubiquitous nature of ISOPOOH exposure, a plausible exposure range of HAEC based on similar previous calculations would be 40–90 μM ISOPOOH/hour (S11), an exposure dose similar to that used in this study [54]. The study of secondary aerosols consisting of higher generation oxidation products such dihydroxydihydroperoxy isoprene (ISO(POOH)2) and additional highly oxygenated oligomers, will serve to improve our understanding of the role of plant-derived organic molecules and their oxidation products in the inhalation toxicology of air pollution.

Previous studies investigating the adverse effects of isoprene-derived SOA have focused on downstream analysis of differential gene expression, specifically alterations in mRNA levels and the use of chemical assays to quantify the oxidative potency of the SOA. In this study, we aimed to characterize early events involved in the mechanism of action underlying the redox toxicology of ISOPOOH in HAEC. By using a quantitative real-time live-cell imaging approach to monitor changes in cellular EGSH we were able to quantify early redox-responses in HAEC exposed to ISOPOOH.

In summary we investigated the early cell responses to oxidative stress induced in HAEC by ISOPOOH exposure as reported by changes in intracellular EGSH as reported by roGFP. Our findings show that exposure to ISOPOOH generates lipid hydroperoxides and that ISOPOOH-induced lipid peroxidation induces changes in the intracellular glutathione redox status of HAEC. These findings demonstrate that ISOPOOH is an environmental hydroperoxide with potency equivalent to H2O2 and t-BOOH that can contribute to the oxidative burden posed by direct exposure of the human airway epithelium to SOA.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Disclaimer

The research described in this article has been reviewed by the Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Agency, nor does the mention of trade names of commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Funding sources

This work was supported by U.S. EPA-University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Toxicology Training Agreement [Grant CR-83591401-0], National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant Nos. T32 ES007126 and TS32 ES007018 and National Science Foundation Grant AGS 2001027.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2022.102281.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Shrivastava M., Cappa C.D., Fan J., Goldstein A.H., Guenther A.B., Jimenez J.L., Kuang C., Laskin A., Martin S.T., Ng N.L., Petaja T., Pierce J.R., Rasch P.J., Roldin P., Seinfeld J.H., Shilling J., Smith J.N., Thornton J.A., Volkamer R., Wang J., Worsnop D.R., Zaveri R.A., Zelenyuk A., Zhang Q. Recent advances in understanding secondary organic aerosol: implications for global climate forcing. Rev. Geophys. 2017;55:509–559. doi: 10.1002/2016RG000540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandis S.N., Harley R.A., Cass G.R., Seinfeld J.H. Secondary organic aerosol formation and transport. Atmos. Environ. Part A, Gen. Top. 1992;26:2269–2282. doi: 10.1016/0960-1686(92)90358-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guenther A.B., Jiang X., Heald C.L., Sakulyanontvittaya T., Duhl T., Emmons L.K., Wang X. The model of emissions of gases and aerosols from nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012;5:1471–1492. doi: 10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiendler-Scharr A., Wildt J., Maso M.D., Hohaus T., Kleist E., Mentel T.F., Tillmann R., Uerlings R., Schurr U., Wahner A. New particle formation in forests inhibited by isoprene emissions. Nature. 2009;461:381–384. doi: 10.1038/nature08292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samet J.M., Zeger S.L., Dominici F., Curriero F., Coursac I., Dockery D.W. 2000. The National Morbidity , Mortality , Part II : Morbidity and Mortality from Air Pollution in the United States Final Version Includes a Commentary by the Institute ’ S Health Review Committee. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee K.K., Miller M.R., Shah A.S.V. Air pollution and stroke. J. Stroke. 2018;20:2–11. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824ea667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnett R.T., Arden Pope C., Ezzati M., Olives C., Lim S.S., Mehta S., Shin H.H., Singh G., Hubbell B., Brauer M., Ross Anderson H., Smith K.R., Balmes J.R., Bruce N.G., Kan H., Laden F., Prüss-Ustün A., Turner M.C., Gapstur S.M., Diver W.R., Cohen A. An integrated risk function for estimating the global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014;122:397–403. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teng A.P., Crounse J.D., Wennberg P.O. Isoprene peroxy radical dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:5367–5377. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arashiro M., Lin Y.H., Zhang Z., Sexton K.G., Gold A., Jaspers I., Fry R.C., Surratt J.D. Effect of secondary organic aerosol from isoprene-derived hydroxyhydroperoxides on the expression of oxidative stress response genes in human bronchial epithelial cells. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts. 2018;20:332–339. doi: 10.1039/c7em00439g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arashiro M., Lin Y.H., Sexton K.G., Zhang Z., Jaspers I., Fry R.C., Vizuete W.G., Gold A., Surratt J.D. In vitro exposure to isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol by direct deposition and its effects on COX-2 and IL-8 gene expression. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016;16:14079–14090. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-14079-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Y.H., Arashiro M., Clapp P.W., Cui T., Sexton K.G., Vizuete W., Gold A., Jaspers I., Fry R.C., Surratt J.D. Gene expression profiling in human lung cells exposed to isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:8166–8175. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b01967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corteselli E.M., Gold A., Surratt J., Cui T., Bromberg P., Dailey L., Samet J.M. Supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids potentiates oxidative stress in human airway epithelial cells exposed to ozone. Environ. Res. 2020;187 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaschler M.M., Stockwell B.R. Lipid peroxidation in cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;482:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander-North L.S., North J.A., Kiminyo K.P., Buettner G.R., Spector A.A. Polyunsaturated fatty acids increase lipid radical formation induced by oxidant stress in endothelial cells. J. Lipid Res. 1994;35:1773–1785. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2275(20)39772-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wages P.A., Cheng W.Y., Gibbs-Flournoy E., Samet J.M. Live-cell imaging approaches for the investigation of xenobiotic-induced oxidant stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2016;1860:2802–2815. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer A.J., Dick T.P. Fluorescent protein-based redox probes. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010;13:621–650. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wages P.A., Silbajoris R., Speen A., Brighton L., Henriquez A., Tong H., Bromberg P.A., Simmons S.O., Samet J.M. Role of H2O2 in the oxidative effects of zinc exposure in human airway epithelial cells. Redox Biol. 2014;3:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbs-Flournoy E.A., Simmons S.O., Bromberg P.A., Dick T.P., Samet J.M. Monitoring intracellular redox changes in ozone-exposed airway epithelial cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013;121:312–317. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-08593-9.00020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavrich K.S., Corteselli E.M., Wages P.A., Bromberg P.A., Simmons S.O., Gibbs-Flournoy E.A., Samet J.M. Investigating mitochondrial dysfunction in human lung cells exposed to redox-active PM components. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018;342:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corteselli E.M., Gibbs-Flournoy E., Simmons S.O., Bromberg P., Gold A., Samet J.M. Long chain lipid hydroperoxides increase the glutathione redox potential through glutathione peroxidase 4. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2019;1863:950–959. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones D.P. Redox potential of GSH/GSSG couple: assay and biological significance. Methods Enzymol. 2002;348:93–112. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)48630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filomeni G., Rotilio G., Ciriolo M.R. Cell signalling and the glutathione redox system. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhee S.G., Kang S.W., Chang T.S., Jeong W., Kim K. Peroxiredoxin, a novel family of peroxidases. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:35–41. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y., Hao H.D., Zhang Q., Wu Y. A broadly applicable mild method for the synthesis of gem-diperoxides from corresponding Ketones or 1,3-dioxolanes. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1615–1618. doi: 10.1021/ol900262t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y., Hao H.D., Wu Y. Facile ring-opening of oxiranes by H2O2 catalyzed by phosphomolybdic acid. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2691–2694. doi: 10.1021/ol900811m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cozens A.L., Yezzi M.J., Kunzelmann K., Ohrui T., Chin L., Eng K., Finkbeiner W.E., Widdicombe J.H., Gruenert D.C. CFTR expression and chloride secretion in polarized immortal human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1994;10:38–47. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.7507342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor-Clark T.E., Undem B.J. Ozone activates airway nerves via the selective stimulation of TRPA1 ion channels. J. Physiol. 2010;588:423–433. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bligh E.G., Dyer W.J. A rapid ethod of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spector A.A. Fatty acid binding to plasma albumin. J. Lipid Res. 1975;16:165–179. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2275(20)36723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennington E.R., Sullivan E.M., Fix A., Dadoo S., Zeczycki T.N., DeSantis A., Schlattner U., Coleman R.A., Chicco A.J., Brown D.A., Shaikh S.R. Proteolipid domains form in biomimetic and cardiac mitochondrial vesicles and are regulated by cardiolipin concentration but not monolyso-cardiolipin. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:15933–15946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid E.M., Richmond D.L., Fletcher D.A. Reconstitution of proteins on electroformed giant unilamellar vesicles. Methods Cell Biol. 2015;128:319–338. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2015.02.004.Reconstitution. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wassall S.R., Leng X., Canner S.W., Pennington E.R., Kinnun J.J., Cavazos A.T., Dadoo S., Johnson D., Heberle F.A., Katsaras J., Shaikh S.R. Docosahexaenoic acid regulates the formation of lipid rafts: a unified view from experiment and simulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:1985–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamanaka K., Saito Y., Sakiyama J., Ohuchi Y., Oseto F., Noguchi N. A novel fluorescent probe with high sensitivity and selective detection of lipid hydroperoxides in cells. RSC Adv. 2012;2:7894–7900. doi: 10.1039/c2ra20816d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., Tinevez J.Y., White D.J., Hartenstein V., Eliceiri K., Tomancak P., Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duh Y.-S., Hui wu X., Kao C.-S. Hazard ratings for organic peroxides. Process Saf. Prog. 2008;27:89–99. doi: 10.1002/prs. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oszajca M., Franke A., Drzewiecka-Matuszek A., Brindell M., Stochel G., Van Eldik R. Temperature and pressure effects on C-H abstraction reactions involving compound i and II mimics in aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:2848–2857. doi: 10.1021/ic402567h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bilan D.S., Belousov V.V. HyPer family probes: state of the art. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2016;24:731–751. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imai H., Nakagawa Y. Biological significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:145–169. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anastasov N., Klier M., Koch I., Angermeier D., Höfler H., Fend F., Quintanilla-Martinez L. Efficient shRNA delivery into B and T lymphoma cells using lentiviral vector-mediated transfer. J. Hematop. 2009;2:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s12308-008-0020-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher A.B., Vasquez-Medina J.P., Dodia C., Sorokina E.M., Tao J.Q., Feinstein S.I. Peroxiredoxin 6 phospholipid hydroperoxidase activity in the repair of peroxidized cell membranes. Redox Biol. 2018;14:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teng A.P., Crounse J.D., Wennberg P.O. Isoprene peroxy radical dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:5367–5377. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sies H. Forum glutathione and its role IN cellular functions. Free. 1999;27:916–921. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00177-x. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/46050158/s0891-5849_2899_2900177-x20160529-27412-14f86yx.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1536069398&Signature=ehuTHdVd35%252FzGzx16hc9l4p7jXw%253D&response-content-disposition=inline%253B fil [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones D.P. Redefining oxidative stress, antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:1865–1879. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatfield D.L., Berry M.J., Gladyshev V.N. 2012. Selenium its Molecular Biology and Role in Human Health. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tong H., Rappold A.G., Diaz-Sanchez D., Steck S.E., Berntsen J., Cascio W.E., Devlin R.B., Samet J.M. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation appears to attenuate particulate air pollution–induced cardiac effects and lipid changes in healthy middle-aged adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120:952–957. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin Z., Chen R., Jiang Y., Xia Y., Niu Y., Wang C., Liu C., Chen C., Ge Y., Wang W., Yin G., Cai J., Clement V., Xu X., Chen B., Chen H., Kan H. Cardiovascular benefits of fish-oil supplementation against fine particulate air pollution in China. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;73:2076–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niki E., Yoshida Y., Saito Y., Noguchi N. Lipid peroxidation: mechanisms, inhibition, and biological effects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;338:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wages P.A., Lavrich K.S., Zhang Z., Cheng W.Y., Corteselli E., Gold A., Bromberg P., Simmons S.O., Samet J.M. Protein sulfenylation: a novel readout of environmental oxidant stress. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015;28:2411–2418. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peralta D., Bronowska A.K., Morgan B., Dóka É., Van Laer K., Nagy P., Gräter F., Dick T.P. A proton relay enhances H2O2 sensitivity of GAPDH to facilitate metabolic adaptation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:156–163. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tristan C., Shahani N., Sedlak T.W., Sawa A. The diverse functions of GAPDH: views from different subcellular compartments. Cell. Signal. 2011;23:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tom C.T.M.B., Crellin J.E., Motiwala H.F., Stone M.B., Davda D., Walker W., Kuo Y.H., Hernandez J.L., Labby K.J., Gomez-Rodriguez L., Jenkins P.M., Veatch S.L., Martin B.R. Chemoselective ratiometric imaging of protein: S-sulfenylation. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:7385–7388. doi: 10.1039/c7cc02285a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Y., Brito J., Dorris M.R., Rivera-Rios J.C., Seco R., Bates K.H., Artaxo P., Duvoisin S., Keutsch F.N., Kim S., Goldstein A.H., Guenther A.B., Manzi A.O., Souza R.A.F., Springston S.R., Watson T.B., McKinney K.A., Martin S.T. Isoprene photochemistry over the Amazon rainforest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016;113:6125–6130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524136113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dovrou E., Bates K., Rivera-Rios J., Cox J., Shutter J., Keutsch F. Towards a chemical mechanism of the oxidation of aqueous sulfur dioxide via isoprene hydroxyl hydroperoxides (ISOPOOH) Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2021:1–16. doi: 10.5194/acp-2021-176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng W.Y., Currier J., Bromberg P.A., Silbajoris R., Simmons S.O., Samet J.M. Linking oxidative events to inflammatory and adaptive gene expression induced by exposure to an organic particulate matter component. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120:267–274. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.