Abstract

Accurate detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is not only necessary for viral load monitoring to optimize treatment in hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 patients, but also critical for deciding whether the patient could be discharged without any risk of viral shedding. Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) is more sensitive than reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and is usually considered the superior choice. In the current study, we compared the clinical performance of RT-qPCR and ddPCR using oropharyngeal swab samples from patients hospitalized in the temporary Huoshenshan Hospital, Wuhan, Hubei, China. Results demonstrated that ddPCR was indeed more sensitive than RT-qPCR. Negative results might be caused by poor sampling technique or recovered patients, as the range of viral load in these patients varied significantly. In addition, both methods were highly correlated in terms of their ability to detect all three target genes as well as the ratio of copies of viral genes to that of the IC gene. Furthermore, our results evidenced that both methods detected the N gene more easily than the ORF gene. Taken together, these findings imply that the use of ddPCR, as an alternative to RT-qPCR, is necessary for the accurate diagnosis of hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, RT-qPCR, ddPCR, Quantitative detection, Clinical performance

1. Introduction

Since its outbreak in December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread rapidly and resulted in a worldwide pandemic https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. In this situation, there is an unprecedented need for diagnostic nucleic acid testing [1,2]. The availability and reliability of rapid nucleic acid tests facilitates the quick identification of infected individuals. This mobilizes the appropriate utilization of scarce public health and medical resources, including those related to contact-tracing, isolation, personal protective equipment, and therapeutic devices [3].

Reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is considered the gold standard method for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection and is routinely used in the epidemiological screening of individuals with suspected COVID-19. However, for hospitalized patients, the sensitivity of RT-qPCR is usually not sufficient to discriminate positive patients with a very low SARS-CoV-2 viral load, from recovered patients without risk of viral shedding [4], [5], [6]. In addition, the inability to quantify the viral load in patients renders it impossible to monitor viral load changes during treatment [6], [7], [8]. Therefore, more sensitive and robust detection methods, especially for low and residual viral load samples, are required for accurate SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and to mitigate the shortcomings of RT-qPCR. Fortunately, digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) provides absolute quantification through Poisson statistics after limiting dilution and endpoint PCR, offering a more sensitive method than RT-qPCR [9,10]. ddPCR has been used to detect small fold changes in copy number variation or gene expression, and rare mutations in cancer diagnostics and infectious disease diagnostics, including dengue virus, hepatitis A virus, norovirus, and SARS-CoV-2 [11], [12], [13], [14], [15].

In hospitalized patients with suspected COVID-19, relying on RT-qPCR to confirm SARS-CoV-2 infection, the accurate detection and precise diagnosis of viral content are helpful and necessary for viral load monitoring and treatment adjustment [7,8]. Additionally, accurate diagnostic techniques are critical for deciding whether the patient has recovered without risk of viral shedding and can be discharged, or the patient is still shedding viral debris and requires further treatment [8,16]. In the present study, we compared the clinical performance of RT-qPCR and ddPCR in patients hospitalized at Huoshenshan Hospital, a temporary hospital built in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China [17]. Furthermore, we assessed the correlation between these two methods in determining RNA copies of different viral genes from different individuals. Our results provide a unique characterization of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in clinical specimens from hospitalized patients who underwent treatment or were awaiting discharge. Additionally, our findings demonstrate a notable correlation between SARS-CoV-2 detection using RT-qPCR and ddPCR and might indicate viral load fluctuations within individuals and the divergence of genome replication within different regions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Clinical specimens

The Huoshenshan Hospital was specifically established to treat COVID-19 patients in response to the outbreak in Wuhan, Hubei, China [17]. All specimens used in this study were obtained from patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection before they were transferred to Huoshenshan Hospital. In total, more than 4,000 patients were admitted and treated in this hospital [17]. All recovered patients must test SARS-CoV-2-negative for two consecutive days before being discharged. Some of these patients might have recovered from the infection during the sampling; therefore, the samples obtained from them tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 and were used as negative controls for our experiments. Oropharyngeal swabs were collected under aseptic conditions and placed in sterile tubes containing viral transport medium. Samples were stored at 4 °C and transported directly to the diagnostic laboratory for further examination.

2.2. RNA extraction

Prior to RNA extraction, all samples were treated at 56 °C for 30 minutes to inactivate SARS-CoV-2. Within 2 hours of inactivation, total viral RNA was extracted from the supernatant using Prefilled Viral Total NA Kit-Flex (KFRPF-805296; Fisher Scientific, LOCATION) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 200 μL specimens were used for extraction, and elution was set to 50 μL. Extracted RNA samples were either immediately subjected to RT-qPCR and ddPCR protocol or stored at -80 °C for further studies.

2.3. Primers and probes

According to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CD), primers and probes targeted ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2. The primer and probe sequences used in the present study were as follows http://ivdc.chinacdc.cn/kyjz/202001/t20200121_211337.html:

-

•

Target 1 (ORF1ab): forward, 5′-CCCTGTGGGTTTTACACTTAA-3′; reverse, 5′-ACGATTGTGCATCAGCTGA-3′; and probe, 5′-FAM-CCGTCTGCGGTATGTGGAAAGGTTATGG-BHQ1-3′.

-

•

Target 2 (N): forward, 5′-GGGGAACTTCTCCTGCTAGAAT-3′; reverse, 5′-CAGACATTTTGCTCTCAAGCTG-3′; and probe: 5′-HEX-TTGCTGCTGCTTGACAGATT-TAMRA-3′.

-

•

Internal control gene (IC gene; RPP30): forward, 5′-AGT GCA TGC TTA TCT CTG ACA G-3′; reverse, 5′-GCA GGG CTA TAG ACA AGT TCA-3′; and probe: 5′-Cy5-TTT CCT GTG AAG GCG ATT GAC CGA-BHQ-3′.

2.4. RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was conducted using the SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection kit (Sansure Co, Ltd, Changsha, China) with the SLAN Real-time PCR System following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the total volume of the reaction mixture was 25 μL and it contained 10 μL RNA template. The reaction conditions were as follows: reverse transcription at 50 °C for 30 minutes; cDNA pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 1 minute; denaturation at 95 °C for 15 seconds (45 cycles), then annealing and elongation (with fluorescence monitoring) at 60 °C for 30 seconds, and a final step at 25 °C for 10 minutes. A cycle threshold (CT) value ≤ 40 indicated a positive result and that >40 represented a negative result. Samples positive for all three genes were considered positive, whereas samples positive for the IC gene and only one viral gene indicated suspected COVID-19 cases. However, samples positive for the IC gene and negative for both viral genes were considered negative. Samples that tested negative for the IC gene were considered defective.

2.5. Digital droplet PCR

Workflow procedures for ddPCR were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions for the RainSure DropX-2000 Droplet Digital PCR System using the RainSure Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Nucleic Acid Detection Kit [19]. Briefly, 25 μL reaction mixture contained 10 μL SARS-CoV-2 one-step RT ddPCR master mix, 4 µL enzyme mix, and 10 μL RNA extracted from patient samples. Firstly, 70 μL droplet generation oil and 25 μL reaction mixture were loaded into an oil well and a sample well, respectively. Thereafter, a gasket with filters was mounted onto the wells of the reagent-loaded cartridges. The cartridges were then loaded into the instrument and the droplet generation process automatically commenced using the following thermal cycling protocol: 49 °C for 20 minutes (reverse transcription); 97 °C for 12 minutes (DNA polymerase activation); 40 cycles at 95.3 °C for 20 seconds (denaturation), and then 52 °C for 1 minutes (annealing); and finally 20 °C (cooling) for infinite hold. The cartridges were then transferred and loaded onto the DScanner-2000 for multi-channel fluorescence detection of droplets. Results were interpreted in a similar manner to those of RT-qPCR.

2.6. Data analysis

Analysis of ddPCR data was performed using the analysis software GeneCount V1.60b0318 (RainSure Scientific). Concentrations of target RNA sequences along with their Poisson-based 95% confidence intervals were provided by the software. The Mann-Whitney test was performed to make comparisons between two groups. Additionally, the Spearman rank correlation test was used to analyze the correlation between the CT values of RT-qPCR and log2 values of copies determined by ddPCR. Computations were performed using R software version 3.6. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Comparing clinical performance of RT-qPCR and ddPCR in hospitalized patients

Among the 130 clinical samples obtained from hospitalized patients, 89, 9, and 32 samples tested positive, suspected, and negative for COVID-19, respectively, using RT-qPCR. Conversely, ddPCR detected 93, 21, and 16 positive, suspected, and negative COVID-19 samples, respectively. Although both methods are considered to have a high specificity, ddPCR demonstrated a higher true positive rate and sensitivity than RT-qPCR (Table 1 ). Furthermore, both methods successfully detected the IC gene in all 130 samples. Regarding the ORF gene, all 89 positive samples detected with RT-qPCR also tested positive using ddPCR (100%). However, 6 of the 41 samples that tested negative for the ORF gene using RT-qPCR, came back positive using ddPCR (14.6%). Moreover, the 98 samples that tested positive for the N gene using RT-qPCR were also positive using ddPCR (100%), although 14 of the 32 samples that tested negative for the N gene using RT-qPCR, tested positive using ddPCR (43.75%) (Table 2 ). These results indicate that ddPCR might be more sensitive than RT-qPCR for detecting the ORF and N genes, although both methods successfully detected the IC gene similarly; this was consistent with the results from previous studies [5,18,19]. Regarding CT values determined using RT-qPCR, CTORF values were higher than CTN values in all 89 positive samples. However, 8 samples (8/89; 8.98%) determined using ddPCR demonstrated a higher valueORF than valueN, which might be due to the higher accuracy with which ddPCR detects viral targets (Supplement Table 1) [20].

Table 1.

Comparison between the ddPCR and RT-qPCR results of the clinical samples.

| RT-qPCR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Suspected | Positive | ||

| ddPCR | Negative | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Suspected | 13 | 8 | 0 | |

| Positive | 3 | 1 | 89 | |

ddPCR = digital droplet PCR; RT-qPCR = real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Table 2.

Comparison between the results of ddPCR and RT-qPCR performed for different targets, using clinical samples.

| RT-qPCR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||

| ddPCR | IC | Negative | 0 | 0 |

| Positive | 0 | 130 | ||

| ORF gene | Negative | 35 | 0 | |

| Positive | 6 | 89 | ||

| N gene | Negative | 18 | 0 | |

| Positive | 14 | 98 | ||

ddPCR = digital droplet PCR; RT-qPCR = real-time polymerase chain reaction.

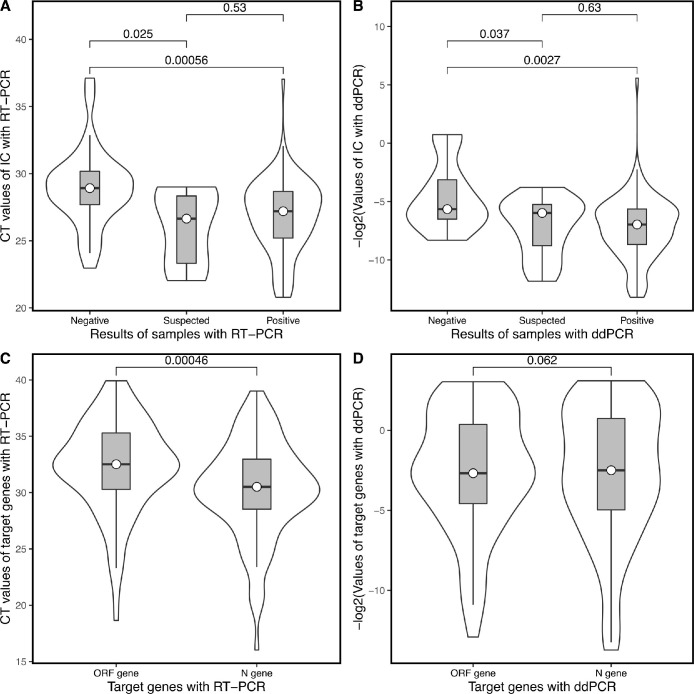

Regarding RT-qPCR, CT values of the IC, ORF, and N genes ranged from 20.79 to 37.03 (median: 27.20), 18.65 to 39.93 (median: 32.52), and from 16.03 to 37.09 (median: 30.21), respectively. The number of copies of the IC, ORF, and N genes ranged from 0.02 to 9425.00 (median: of 146.10), 0.12 to 7727.00 (median: 6.42), and from 0.14 to 13561.00 (median: of 8.814), respectively, when using ddPCR. For both RT-qPCR and ddPCR techniques, the median CT value of the IC gene was higher in the COVID-19-negative group than that in the COVID-19-positive group (Fig. 1 A and B). Moreover, higher CT values of the IC gene in negative samples indicated lower total RNA content compared to positive samples. This might be due to poor sampling techniques, which result in lower viral content collected on oropharyngeal swabs.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the distribution of results obtained with RT-qPCR and ddPCR. (A) CT values of the IC gene in negative, suspected, and positive samples determined using RT-qPCR. (B) -log2 values of the IC gene in negative, suspected, and positive samples determined using ddPCR. (C) CT values of the ORF and N genes determined using RT-qPCR. (D) CT values of the ORF and N genes determined using ddPCR. P values are included in the box. CT = cycle threshold; ddPCR = digital droplet PCR; IC gene = internal control gene; RT-qPCR = real-time polymerase chain reaction.

The median CT values of the ORF gene were higher than those of the N gene, detected using RT-qPCR [19]; however, there were no obvious differences noted when using ddPCR (Fig. 1C and D). This suggests that further study is required regarding individual differences of these two methods.

3.2. Correlation between results obtained using RT-qPCR and ddPCR

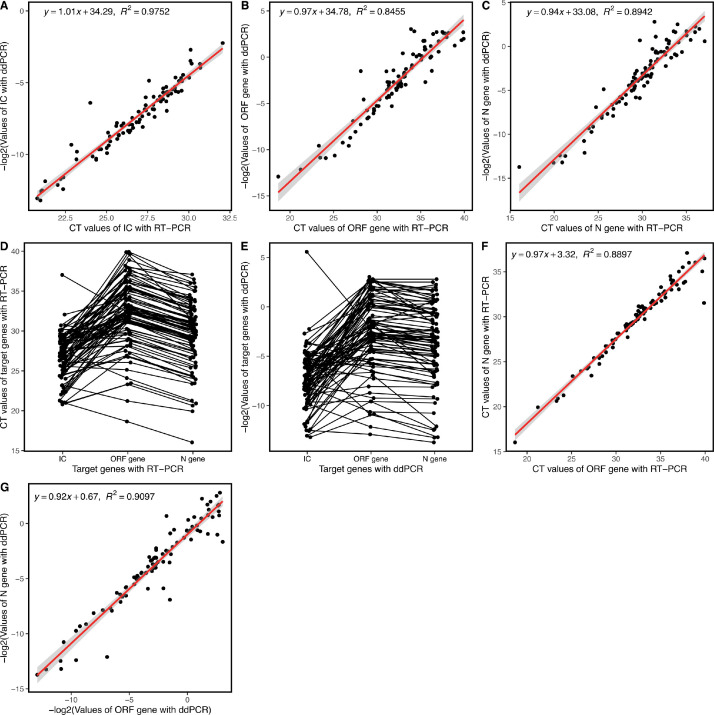

Considering that RT-qPCR and ddPCR are semi-quantitative and quantitative detection methods, respectively, we aimed to explore whether any correlation existed between these two methods. Surprisingly, for all 89 COVID-19-positive samples detected in several different batches, we identified that the results for all three target genes demonstrated a high correlation between RT-qPCR and ddPCR techniques. Particularly, R2 values of 0.9752, 0.8455, and 0.8942 were calculated for the IC, ORF, and N genes, respectively (Fig. 2 A–C). These results indicate that although the CT value determined using RT-qPCR is considered relatively quantitative, R2 values are more accurate for determining the absolute content of the target gene (i.e., viral load) in detecting SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, contrary to prior belief that only valuable qualitative results were obtained from RT-qPCR, we might be able to compare the viral load of different samples using their CT value determined using RT-qPCR [6].

Fig. 2.

Correlation analysis between the CT values and -log2 values determined by RT-qPCR and ddPCR, respectively, for the IC gene (A), ORF gene (B), and N gene (C). Comparison of deviations of values obtained for each sample ran using the same method. (A) CT values of the three target genes determined using RT-qPCR. (B) -log2 values of the three target genes determined using ddPCR. Correlation analysis between the ORF and N genes. (A) CT values determined with RT-qPCR. (B) -log2 values determined by ddPCR. CT = cycle threshold; ddPCR = digital droplet PCR; IC gene = internal control gene; RT-qPCR = real-time polymerase chain reaction.

3.3. Correlation between copy numbers of the ORF and N genes determined using either RT-qPCR or ddPCR

A single SARS-CoV-2 genome only contains one copy of both the ORF and N genes. This suggests that copies of the ORF gene should be equal to those of the N gene [21]. However, RT-qPCR-revealed CT values of the ORF gene were higher than those of the N gene in most samples. These results suggest that the N gene consisted of more nucleic acids than the ORF gene within the same sample, where amplification efficiency was not considered. Moreover, ddPCR also detected that most of the copy values of the ORF gene were lower than those of the N gene at the individual level (Fig. 2D and E) [20]. Interestingly, the ddPCR method detected no significant differences between the overall values of the ORF and N genes (Fig. 2D). This might be due to a few exceptions in which outlying results misrepresented the overall effects, indicating that a more detailed comparison is necessary for analyzing absolute quantitative results obtained with ddPCR.

The CT values of the ORF and N genes demonstrate a strong correlation, using both RT-qPCR (R2= 0.8897) and ddPCR detection methods (R2= 0.9097), as presented in Fig. 2F and G. The correlation between the ORF and N genes in any one method elucidated that these two target genes, within the viral genome, are closely related [6,20]. In general, both methods were more sensitive for the detection of the N gene than the ORF gene [20].

3.4. Correlation between ratios of any two of the three target genes

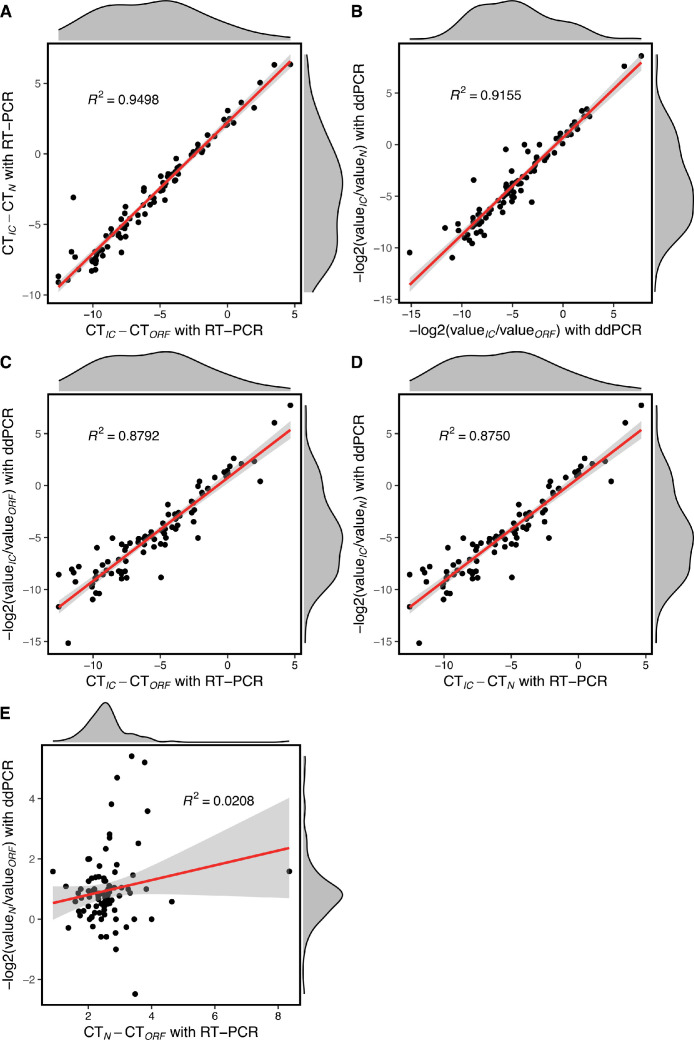

As described above, we confirmed that the values of the ORF and N genes exhibited a linear correlation in any one detection method. Moreover, the detection of all three target genes also had a linear correlation across both methods. Therefore, we pondered whether the ratio between any two target genes was correlated within the same method or between the two methods. To further determine the correlation of the ratio between any two targets, we used CTIC/ CTORF, CTIC/ CTN, and CTORF/ CTN for RT-qPCR and log2(valueIC/valueORF), log2(valueIC/valueN), and log2(valueORF/valueN) for ddPCR.

We identified that CTIC/ CTORF and CTIC/ CTN demonstrated a very strong linear correlation in the RT-qPCR method, with a similar result verified with ddPCR (Fig. 3 A and B). Moreover, a linear correlation was detected between CTIC/ CTORF in RT-qPCR and log2(valueIC/valueORF) in ddPCR, with similar results obtained regarding these ratios for the N gene (Fig. 3C and D). Unsurprisingly, we did not observe any correlation between CTORF/ CTN in RT-qPCR and log2(valueORF/valueN) in ddPCR (Fig. 3E). The ratio of copies of viral genes compared to that of the IC revealed that individuals have fluctuating viral loads to some extent, and a very strong correlation within and between the two methods. This indicates that the analysis of these ratios is reliable and could efficiently reflect variable virus loads during infection.

Fig. 3.

Correlation analysis among ratios of the three target genes determined using the same or different method. (A) Correlation between CTIC/ CTORF and CTIC/ CTN determined using RT-qPCR. (B) Correlation between −log2(valueIC/ valueORF) and -log2(valueIC/ valueN) determined using ddPCR. (C) Correlation between CTIC/ CTORF and −log2(valueIC/ valueORF) determined by RT-qPCR and ddPCR, respectively. (D) Correlation between CTIC/ CTN and −log2(valueIC/valueN) determined by RT-qPCR and ddPCR, respectively. (E) Correlation between CTN/ CTORF and −log2(valueN/valueORF) determined by RT-qPCR and ddPCR, respectively. CT = cycle threshold; ddPCR = digital droplet PCR; IC gene = internal control gene; RT-qPCR = real-time polymerase chain reaction.

4. Discussion

Positive specimens, obtained by screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection among suspected COVID-19 cases, were sampled from patients during the early phase of infection. Therefore, the qualitative observation of viral infection was generally sufficient to help make correct medical decisions [1]. For hospitalized COVID-19 patients, nucleic acid testing for the detection of viral RNA is usually required when patients have obviously recovered and are awaiting discharge, or when patients experience worsening of symptoms and require treatment optimization [6,8]. Therefore, it may be possible to characterize viral load fluctuation in these patients [[6], [7], [8]]. The results of RT-qPCR and ddPCR performed using specimens collected from hospitalized COVID-19 patients demonstrate that ddPCR is indeed more sensitive than RT-qPCR. Moreover, negative specimens might be the result of poor sampling techniques, as the viral load in these patients varied significantly [18,19,[22], [23], [24]].

Both methods demonstrated a strong correlation regarding the detection of all three target genes, and between the ratio of the copies of viral genes to that of the IC gene. These results indicate that the CT values of genes detected using RT-qPCR could be used to evaluate the number of viral copies in a specimen when it was not possible to utilize ddPCR to directly determine viral copies [6,20]. Furthermore, our results evidence that the N gene was more easily detected by both methods, which might be due to the efficiency of amplification and fluorescence monitoring of these two genes as well as their primers and probes [8,20]. This might indicate a distinction between primers, probes, polymerase, and reaction mixtures, or imply deviations of genome replication or stability within the N and ORF regions, which requires further study [19].

In summary, we compared the clinical performance of RT-qPCR and ddPCR in detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection in oropharyngeal swab samples from hospitalized patients. Results indicated that ddPCR is indeed more sensitive than RT-qPCR. Additionally, COVID-19-negative specimens might result from poor sampling techniques, as the viral load in these patients varies significantly. All three target genes and their ratios demonstrated strong correlations between both methods; however, both methods were more sensitive for detecting the N gene than the ORF gene. Our results evidence that ddPCR should be used as an alternative to RT-qPCR for the accurate diagnosis of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients.

Authors’ contributions

Jingyuan Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing original draft. Weishi Lin: Methodology, Writing original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Pibo Du: Conceptualization, Writing original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis. Wei Liu: Resources, Validation. Xiong Liu: Resources, Validation. Chaojie Yang: Resources, Validation. Ruizhong Jia: Resources, Validation. Yong Wang: Resources, Validation. Yong Chen: Resources, Validation. Leili Jia: Resources, Validation. Li Han: Investigation, Visualization. Weilong Tan: Software, Data curation. Nan Liu: Investigation, Visualization. Junjie Du: Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Yuehua Ke: Project administration, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition. Changjun Wang: Project administration, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC1202905), National Key Program for Infectious Diseases of China (2018ZX10732401-001, 2018ZX10713003-001), COVID-19 Research Program (YJGG2020-01, YJGG2020-02), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671977).

Disclaimer

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2022.115677.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Binnicker MJ. Challenges and controversies to testing for COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(11):e01695–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01695-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilic T, Weissleder R, Lee H. Molecular and immunological diagnostic tests of COVID-19: current status and challenges. iScience. 2020;23(8):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers R, O’Brien T, Aridi J, Beckwith CG. The COVID-19 diagnostic dilemma: a clinician’s perspective. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(8):e01287–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01287-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tahamtan A, Ardebili A. Real-time RT-PCR in COVID-19 detection: issues affecting the results. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20(5):453–454. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2020.1757437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veyer D, Kerneis S, Poulet G, Wack M, Robillard N, Taly V, et al. Highly sensitive quantification of plasma SARS-CoV-2 RNA shelds light on its potential clinical value. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;73(9):e2890–e2897. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, Yang S, Wang L, Tang Y, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):793–798. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fajnzylber J, Regan J, Coxen K, Corry H, Wong C, Rosenthal A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Muller MA, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milosevic D, Mills JR, Campion MB, Vidal-Folch N, Voss JS, Halling KC, et al. Applying standard clinical chemistry assay validation to droplet digital PCR quantitative liquid biopsy testing. Clin Chem. 2018;64(12):1732–1742. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.291278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salipante SJ, Jerome KR. Digital PCR-an emerging technology with broad applications in microbiology. Clin Chem. 2020;66(1):117–123. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2019.304048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abachin E, Convers S, Falque S, Esson R, Mallet L, Nougarede N. Comparison of reverse-transcriptase qPCR and droplet digital PCR for the quantification of dengue virus nucleic acid. Biologicals. 2018;52:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coudray-Meunier C, Fraisse A, Martin-Latil S, Guillier L, Delannoy S, Fach P, et al. A comparative study of digital RT-PCR and RT-qPCR for quantification of Hepatitis A virus and Norovirus in lettuce and water samples. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;201:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Feng J, Zhang Q, Guo D, Zhang L, Suo T, et al. Analytical comparisons of SARS-COV-2 detection by qRT-PCR and ddPCR with multiple primer/probe sets. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1175–1179. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1772679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persson S, Eriksson R, Lowther J, Ellstrom P, Simonsson M. Comparison between RT droplet digital PCR and RT real-time PCR for quantification of noroviruses in oysters. Int J Food Microbiol. 2018;284:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suo T, Liu X, Feng J, Guo M, Hu W, Guo D, et al. ddPCR: a more accurate tool for SARS-CoV-2 detection in low viral load specimens. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1259–1268. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1772678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.To KK, Tsang OT, Leung WS, Tam AR, Wu TC, Lung DC, et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhihui W, Sibing Z, Bin L, Yufeng G, Fangzhou Y. Practice and reflection on COVID-19 specialized hospital construction and management in Wuhan(in Chinese) Hosp Admin J Chin PLA. 2020;27(03):201–203. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falzone L, Musso N, Gattuso G, Bongiorno D, Palermo CI, Scalia G, et al. Sensitivity assessment of droplet digital PCR for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Int J Mol Med. 2020;46(3):957–964. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao M, Rashid FA, Sabri F, Jamil NN, Zain R, Hashim R, et al. Comparing nasopharyngeal swab and early morning saliva for the identification of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;72(9):e352–e356. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen H, Wu R, Xing Y, Du Q, Xue Z, Xi Y, et al. Influence of different inactivation methods on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA copy number. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(8):e00958–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00958-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D, Lee JY, Yang JS, Kim JW, Kim VN, Chang H. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome. Cell. 2020;181(4):914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dang Y, Liu N, Tan C, Feng Y, Yuan X, Fan D, et al. Comparison of qualitative and quantitative analyses of COVID-19 clinical samples. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;510:613–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Kock R, Baselmans M, Scharnhorst V, Deiman B. Sensitive detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 by multiplex droplet digital RT-PCR. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;40(4):807–813. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-04076-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muenchhoff M, Mairhofer H, Nitschko H, Grzimek-Koschewa N, Hoffmann D, Berger A, et al. Multicentre comparison of quantitative PCR-based assays to detect SARS-CoV-2, Germany, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(24):1–9. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.24.2001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.