Abstract

Background

Abdominal organ cluster transplantation for the treatment of upper abdominal end-stage diseases is a serious conundrum for surgeons.

Case Report

We performed clinical assessment of quadruple organ transplantation (liver, pancreas, duodenum, and kidney) for a patient with end-stage liver disease, post-chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis, uremia, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and explored the optimal surgical procedure. Simultaneous classic orthotopic liver, pancreas-duodenum, and heterotopic renal transplantation was performed on a 46-year-old man. The process was an improvement of surgery implemented with a single vascular anastomosis (Y graft of the superior mesenteric artery and the celiac artery open together in the common iliac artery). The pancreatic secretions and bile were drained through a modified uncut jejunal loop anastomosis, and the donor’s kidneys were placed in the right iliac fossa. The patient was prescribed basiliximab, glucocorticoid, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil for immunosuppression. The hepatic function recovered satisfactorily on postoperative day (POD) 3, and pancreatic function recovered satisfactorily in postoperative month (POM) 1. Hydronephrosis occurred in the transplanted kidney, with elevated creatinine on POD 15. Consequently, renal pelvic puncture and drainage were performed. His creatinine dropped to a normal level on POD 42. No allograft rejections or other complications, like pancreatic leakage, thrombosis, or localized infections, occurred. The patient had normal liver, renal, and pancreas functions with insulin-independent after POD 365.

Conclusions

Simultaneous classic orthotopic liver, pancreas-duodenum, and heterotopic renal transplantation is a promising therapeutic option for patients with insulin-dependent diabetes combined with end-stage hepatic and renal disease, and our center’s experience can provide a reference for clinical multiorgan transplantation.

Keywords: Islets of Langerhans Transplantation; Kidney Transplantation; Liver Cirrhosis; Liver Transplantation; Organ Transplantation; Transplantation, Isogeneic

Background

Abdominal multiorgan transplantation is effective for patients with multiple organ failure (MOF). Combined liver-kidney transplantation (CLKT), simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation (SKPT) with enteric drainage of pancreatic exocrine secretions, and simultaneous orthotopic liver and heterotopic pancreas-duodenum transplantation (SLPT) can be indicated for patients with failure of both organs. All of these combinations have been reported in the literature [1].

Combined liver, pancreas-duodenum, and kidney transplantation (LPDKT) has only been performed in a few cases as a therapeutic approach for patients with end-stage liver disease combined with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus with renal failure. Such patients are rare, and there is no causal connection among end-stage liver disease, diabetes, and chronic renal failure. Patients with simultaneous failure of 3 organs often have difficulty tolerating surgery due to their poor physical condition [2]. LPDKT is complex because the perioperative hemodynamics are unstable, and it is difficult to adjust the use of drugs during and after surgery, which makes successfully combined transplantation challenging. According to statistics, the 5-year survival rates of diabetic patients after liver transplantation are significantly lower than those of nondiabetic patients, so diabetic patients must strictly control their blood glucose level after organ transplantation to keep it in the normal range [3,4]. Herein, we discuss a case where 1 patient with end-stage liver disease, post-chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis, uremia, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) was successfully transplanted and recovered, the details of surgical techniques, and immunosuppressive treatment regimens.

Case Report

A 46-year-old man was diagnosed with kidney stones and high creatinine (up to 1100 μmol/L) in 2008, and, after repeated extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and creatinine-lowering therapy, his renal function remained poor. Two months later, he was found to be positive for hepatitis B surface antigen and was diagnosed with IDDM, but he was not followed up regularly. Abdominal pain, conjunctival bleeding, and gastrointestinal bleeding occurred intermittently in the following 10 years. Additionally, he started regular dialysis (3 times per week) because of chronic renal failure. He underwent insulin therapy (48 units/day) and showed a history of repeated hypoglycemic episodes. In addition, the patient developed abdominal distension, fatigue, and anorexia 2 months prior and was hospitalized with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

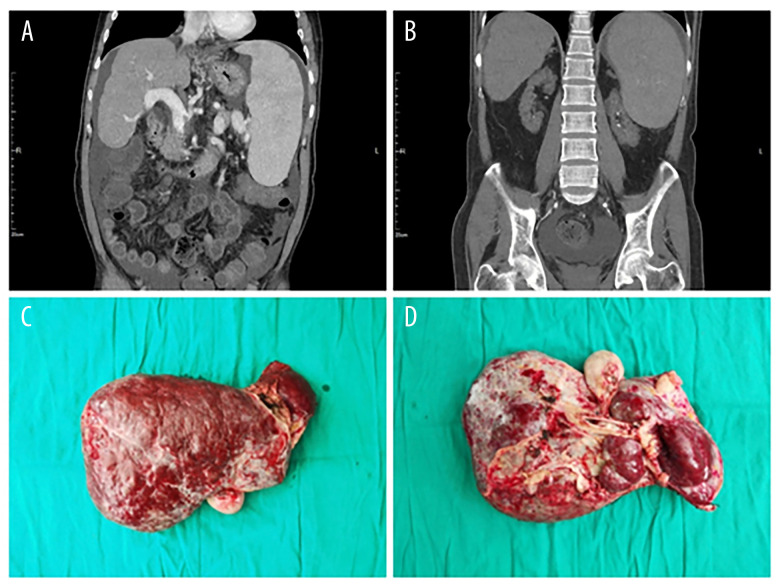

A physical examination identified discomfort in the right upper abdomen, abdominal distension, and positive shifting dullness. The laboratory examination results and the imaging descriptions are clubbed with an end-stage liver and renal disease (Table 1 and Figure 1A, 1B). Thus, this patient was diagnosed with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B with chronic renal function failure and uremia, IDDM, and kidney stones (Figure 1C, 1D). After much clinical multidisciplinary testing, deliberation, and care, management concluded that the strategy of transplant would offer the best survival benefit. The patient was well-suited to a combined liver, pancreas-duodenum, and kidney transplant.

Table 1.

Preoperative laboratory examination results of the patient.

| Items | Value |

|---|---|

| Routine blood examination | |

| WBC (×109/L) | 2.49 |

| RBC (×1012/L) | 3.30 |

| Hb (g/L) | 79 |

| PLT (1012/L) | 44 |

| Routine urine | |

| Protein | ++ |

| Occult blood | ++++ |

| Liver function | |

| ALT (U/L) | 27 |

| AST (U/L) | 33 |

| ALB (g/L) | 37 |

| ALP (U/L) | 175 |

| TBil (umol/L) | 13.5 |

| Renal function | |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 15.5 |

| CRE (umol/L) | 788 |

| Hepatitis B virus serum markers | |

| HBsAg | + |

| HBeAg | + |

| HBcAg | + |

| HBV-DNA (U/ml) | <100 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 11.2 |

| Postprandial blood sugar (mmol/L) | 19.7 |

| Ultrasonography | Cirrhosis, ascites, splenomegaly, atrophy of both kidneys, gallbladder polyps and thickening of the gallbladder wall, a slightly larger prostate |

| Computed tomography | Cirrhosis, ascites, portal hypertension, esophageal and gastric varices, thrombosis in the proximal portal vein and superior mesenteric vein, splenomegaly, ascites, atrophy of both kidneys, multiple kidney cysts and stones; abdominal aorta and bilateral common iliac arteriosclerosis |

WBC – white blood cells; RBC – red blood cells; Hb – hemoglobin; PLT – platelet; ALT – alanine aminotransferase; AST – aspartate aminotransferase; ALB – albumin; ALP – alkaline phosphatase; TBil – total bilirubin; BUN – blood urea nitrogen; CRE – creatinine; HBsAg – hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg – hepatitis B e antigen; HBcAg – hepatitis B core antibody.

Figure 1.

(A, B) Preoperative CT examination shows severe liver cirrhosis, splenomegaly, and atrophy of both kidneys. (C, D) Intraoperative resection of the diseased liver.

He received en bloc liver, pancreas, partial duodenum, and kidney grafts from a donor aged 36 years, that were trimmed using routine methods [5,6]. The organ cluster was preserved in University of Wisconsin solution, and the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) sites of the donor and recipient are shown in Table 2. A liver biopsy of the graft showed no steatosis. The en bloc liver, pancreas, partial duodenum, and both kidneys were retrieved without disturbing the hepatoduodenal ligament, and the bilateral iliac vessels were kept for backup. The openings of the internal iliac artery and external iliac artery of the donor Y graft were anastomosed with the superior mesenteric artery and celiac arteries, respectively, of the same donor organ cluster to form a single opening of the common iliac artery for a single vascular anastomosis (Supplementary Figure 1). The bile was directly released from the major extrahepatic bile duct into the duodenum as the bile duct remained intact. The blood flow of the superior mesenteric vein beyond the neck of the pancreas was interrupted.

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of the recipient and donors.

| Recipient/donor | Gender | Age | Source of donors | Organ types | HLA sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | Male | 46 | – | – | A2; A2; B46; B51; DR9; DR15 |

| Donor | Male | 36 | DBD | Liver, pancreas, duodenum, right kidney | A2; A33; B51; B58; DR17; DR1404 |

DCD – donation after citizen’s death; HLA – human leukocyte antigen.

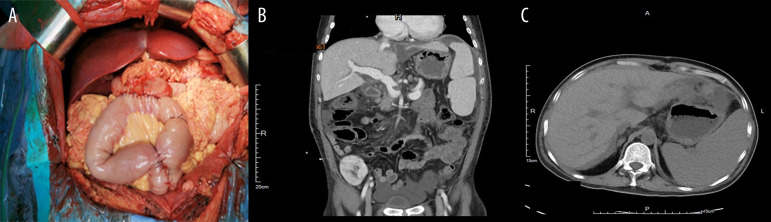

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia. An abdominal incision under the bilateral costal margin was made, and the white line on the abdomen was extended upward to below the xiphoid process. The classical technique with cava cross-clamping of hepatectomy was performed in the removal process of diseased organs. The liver was transplanted orthotopically without using vein-venous bypass, together with the whole duodenum-pancreatic graft. Subsequently, the suprahepatic and infrahepatic inferior vena cava were anastomosed, and then 600 ml fresh frozen plasma was infused through the portal vein during the anastomosis, and it was anastomosed to the portal vein of the recipient and the graft sequentially with end-to-end continuous valgus sutures. End-to-end anastomosis was created between the opening of the common iliac artery of the donor organ cluster and the recipients’ hepatic artery. The infrahepatic inferior vena cava was loosened, the portal vein and hepatic artery were reperfused, and the suprahepatic inferior vena cava was loosened to restore the donor organ hemodynamics. After reperfusion, the graft liver and pancreas were well perfused, with normal color. Finally, a modified uncut jejunal loop anastomosis (a Warren anastomosis) was performed between the graft duodenum and the recipient’s jejunum for transplanted pancreatic exocrine and biliary drainage. The pancreatic exocrine secretions were drained enterically to the jejunum and the allograft pancreas was left in place instead of performing orthotopic pancreas transplantation. The allograft kidney was placed in the right iliac fossa according to the traditional classical manner (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Intraoperative anastomosis. (B, C) Postoperative CT scan.

The total surgery duration was 435 min, with 60 min in the anhepatic phase. The total cold ischemia time was 7 h, with a warm ischemia time of 5 min. A total of 23 units of red cell suspension were transfused. Regular monitoring was performed of routine blood and urine tests, blood and urine bilirubin, blood and urine amylase, serum C-peptide, liver and kidney function, blood sugar, blood coagulation, D-dimer, tacrolimus (FK506) blood concentration, and immune index after the operation. The quadruple immunosuppressive regimen included induction with basiliximab (Simulect) and maintenance therapy with tacrolimus (target trough level 8–10 ng/mL)+mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 0.72 g/day+prednisone acetate (Pred) was used in the early-stage after transplant and a gradual transition to maintenance therapy with tacrolimus alone. The Pred was tapered down and completely withdrawn within 20 days after transplant. Additionally, anti-coagulative, anti-infectious, inhibitory of gastric acid and pancreatic enzyme secretion, and nutritional supportive therapies were given routinely after surgery.

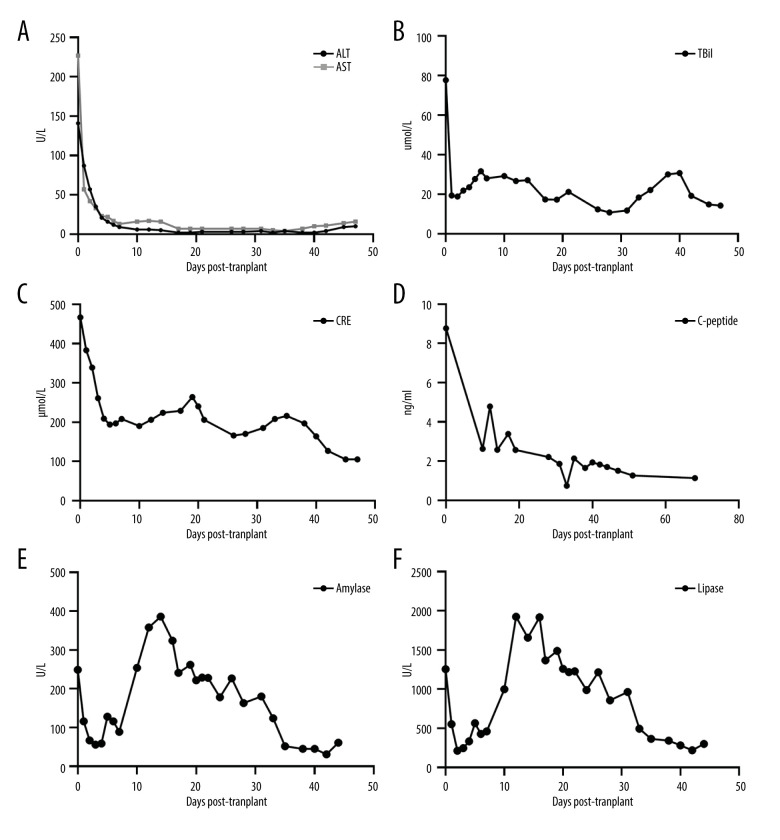

The peak values of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBil), and creatinine (CRE) on postoperative day 1 (POD) were 141 U/L, 227 U/L, 77.6 μmol/L, and 467 μmol/L, respectively. The values of ALT, AST, TBil, and CRE were 9 U/L, 13 U/L, 28.0 μmol/L, and 194 μmol/L, respectively, and insulin was completely discontinued on POD 7. The value of C-peptide was 2.58 ng/mL on POD 14 (Figure 3A–3F). Ultrasonography showed that the blood flow of the transplanted organs was normal. On POD 15, the transplanted kidney experienced mild to moderate fluid effusion, but the symptoms improved after the right transplanted kidney was punctured and drained. The serum creatinine decreased steadily in the early stage and returned to normal on POD 42. Amylase lipase fluctuated in the early stage after the operation, but the symptoms improved after fasting, nutritional supplementation, and somatostatin treatment. The amylase level returned to normal on POD 33 and was stable, without complications such as vascular embolism, pancreatic fistula, or local infection. The transplanted liver, kidney, and pancreas of the patient were all stable on POD 47 (Figure 2B, 2C) and the patient was discharged routinely.

Figure 3.

Changes in organ functions after transplantation. (A) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). (B) Total bilirubin (TBil). (C) Creatinine (CRE). (D) C-peptide. (E) Amylase. (F) Lipase.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Clinical Research and Animal Trials of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, and an informed consent waiver was granted by the IEC given the retrospective nature and minimal risk of the study. The patient gave consent for his details and accompanying images to be published.

Discussion

Classic orthotopic liver transplantation combined with heterotopic pancreas transplantation is the standard treatment for chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis, IDDM, and uremia. There are few reports (Table 3 [7–11]) on the treatment of combined LPDKT in patients with end-stage liver disease, renal disease, and IDDM because patients with all these conditions are rare. There is no conclusive evidence yet to suggest an internal causative relationship among end-stage liver disease, chronic renal failure, and diabetes.

Table 3.

Multiorgan liver-pancreas-kidney transplantation.

| Ref. | Grafts | Immunosuppressive program | Complication | Graft function recovery time | Follow-up time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Kidney | Pancrea | |||||

| Jiang Li et al, 2017 | Liver Duodenopancreas Kidney |

Basiliximab, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids | Non | 15 days | 15 days | 3 weeks | 3 weeks |

| Tzakis AG et al, 2015 | Liver Pancreas Kidney |

Tacrolimus and steroids | All three transplanted organs acute rejection | 2 months | 2 months | 2 months | 18 months |

| Rivera E et al, 2016 | Liver Pancreas Kidney |

Thymoglobulin, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids | Liver and pancreas acute rejection | NA | 45 days | NA | 18 months |

| Zhang G et al, 2020 | Liver Duodenopancreas Kidney |

rabbit anti-human thymocyte immunoglobulin (ATG), FK506, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone acetate (Pred) | Transplant again for the kidney acute rejection | 7 days | 20 days | 7 days | 14 years |

| Luis A et al, 2017 | Liver Pancreas Kidney |

Tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, prednisolone | Non | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA – not applicable.

Surgical treatment of patients with multiple organ failure is often difficult because of the patients’ poor physical condition. The complex surgical process, unstable hemodynamic changes [12], and many contradictions regarding the adjustments of medication during and after the operation increase the difficulty of a successful combined LPDKT. However, this type of surgery will reduce the complications of pancreas transplantation affecting a previously transplanted liver, such as vascular embolism, pancreatitis, or a local abscess. Moreover, it can also reduce the damage to the liver produced by pancreatic complications when reoperation is required, and it will facilitate the operation, but this technique is very difficult [13]. Some studies have shown that combined liver transplantation can reduce the recipient’s rejection of the transplanted organs, while the insulin and glucagon produced by the pancreas have nutritional protective effects on the liver [14,15]. The pancreas relies on portal vein reflux, which makes the metabolism of insulin more stable [16].

Therefore, combined pancreas transplantation should be considered for patients with organ failure complicated with diabetes. The grafts should all be taken from the same donor with a similar genetic background and antigenicity. This will produce fewer donor-specific antibodies than grafts from different donors. The symptoms of diabetes can be corrected at the same time as uremia and liver failure. Combined en bloc liver-pancreas transplantation has been proven to be effective in treating end-stage liver disease with IDDM [17,18]. Zhang et al [7] reported the long-term effects of liver-kidney-pancreas transplant for patients with advanced liver disease, hepatitis B cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, and chronic pancreatitis caused by insulin-dependent diabetes, and achieved satisfactory long-term effects after 14 years of follow-up, without any rejection or other complications. Kornberg et al [19] reported SLPT for 14 liver cirrhosis and IDDM patients. All recipients could discontinue insulin therapy shortly after the operation. The 7-year survival rate of the recipients was as high as 64.2%, and only 1 patient experienced diabetes relapse. Li et al [9] reported simultaneous LPDKT in a patient with hepatitis B cirrhosis, uremia, and IDDM. The patient was hospitalized for 47 days and did well with normalization of transplanted organ function. Therefore, combined LPDKT is effective in the treatment of diabetes with liver and kidney failure and has better long-term effects than combined liver-kidney transplantation.

Like the original technique of pancreas graft exocrine drainage, the bladder-drained grafts always had to be revised to enteric drainage owing to complications such as urinary tract infections, metabolic acidosis, and reflux pancreatitis from urinary retention. Bladder drainage may have a selective benefit to allow for an earlier diagnosis of graft rejection by allowing monitoring of urinary amylase levels, but its status has been questioned because of improvements in immunosuppression. Subsequently, enteric drainage becomes another most physiologic approach for drainage of exocrine secretions.

According to data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and the International Pancreatic Transplant Registry (IPTR) [20,21], from 2006 to 2016, 8.4% of pancreases underwent bladder drainage, 18.5% underwent enteric drainage using a Roux limb, and 66.4% underwent enteric drainage without a Roux limb. The survival rates of recipients and grafts for all strategies were similar. Enteric drainage is preferred because it can drain pancreatic secretions into the dysfunctional intestine, thereby transferring the contents of the small intestine from the transplanted duodenal-jejunal anastomosis. However, it can be easier to achieve graft rescue if the duodenum-jejunum anastomosis leaks when perforation occurs [22].

To improve the surgical process, the donor’s superior mesenteric artery and celiac arteries were anastomosed to a Y graft of the internal iliac artery and external iliac artery from the same donor to allow for a single vascular anastomosis (the common iliac artery) (Supplementary Figure 1). The artery and the recipient’s hepatic artery were anastomosed in an end-to-end fashion. The procedure of single opening vascular reconstruction is completed during the pruning of the organ clusters, which can appropriately prolong the vascular pedicle and shorten the anhepatic phase to make the anastomosis operation more convenient. It has been reported [23] that a long anhepatic phase will aggravate the ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) of the graft, which is of great significance for the recovery of postoperative organ function. After reperfusion of the organ cluster, we performed a modified uncut jejunal loop anastomosis (a Warren anastomosis) between the graft duodenum and recipient’s jejunum for exocrine pancreatic and biliary drainage. Warren anastomosis is a new anastomosis method for choledochojejunostomy, performed behind the antrum pyloricum after lifting the jejunum 15–20 cm away from the ligament of Treitz to the hilar of the liver and anastomosed end-to-side with the bile duct stump, and then the proximal jejunum is anastomosed side-to-side with the bile-draining jejunal loops 40 cm from the bile-enteric anastomosis to form a loop [24,25]. Compared with patients undergoing Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy, this surgical procedure is performed without cutting off the jejunum. Only the intestinal tube is ligated, and its normal electrophysiological conduction is not disrupted. Therefore, it is more conducive to the drainage of pancreatic juice, bile, and intestinal contents, reducing the incidence of intestinal loop motility disorders. The patient’s anus exhausts faster, and gastrointestinal function is recovered faster after surgery.

Donor organs are easy to procure and trim for multiple organ transplantation. Only 4 to 5 vessels need to be anastomosed during transplantation to make a jejunal anastomosis without a biliary anastomosis. In addition, the bile and pancreatic juice enter the recipient directly through the duodenum, which is more in line with the normal physiological function. Therefore, classic orthotopic liver transplantation, pancreas-partial duodenal transplantation, and heterotopic kidney transplantation are the best choices. In this case, the patient had end-stage liver disease, post-chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis, uremia, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. After combined transplantation, exogenous insulin was stopped. The function of the liver and kidney and blood glucose levels returned to normal and satisfactory results were achieved.

Allograft rejection is still one of the important factors affecting the efficacy of organ cluster transplantation [26]. There is no perfect immunosuppressive program for multiple organ transplantation due to the small number of cases. At present, many researchers advocate that a combined immunosuppressive regimen should be used after hepatopancreas-duodenal organ cluster transplantation. The quadruple immunosuppressive regimen of this patient was based on basiliximab, tacrolimus, MMF, and Pred, and no allograft rejection occurred within 47 days after transplantation. Basiliximab was used to induce immunity at the end of the operation and on POD 4. The concentration of tacrolimus was stabilized to 8–10 μg/L in the first 3 months. The application of hormones can easily induce postoperative hyperglycemia and diabetes recurrence, and it is recommended that postoperative hormones be quickly reduced and discontinued early for such patients. Our patient recovered and was discharged home after 47 days of hospitalization, insulin-independent, and maintaining a healthy diet and good physical condition 365 days after transplant.

Decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B is an absolute indication for liver transplantation, but it is necessary to prevent hepatitis B virus reinfection in the early period after surgery. We used high-dose anti-hepatitis B immunoglobulin to prevent hepatitis B virus infection during and after surgery, checked his HsBAb and HBV DNA regularly, and adjusted the dosage of anti-hepatitis B immunoglobulin. Preventing the recurrence of hepatitis is key for long-term survival [27].

This article reports a rare case in which the patient was diagnosed with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B with chronic renal function failure and uremia, IDDM, and kidney stones. We discussed the necessity of choosing this technique. The main advantage of this technique is its rapidity because of rebuilding the vessels in ex vitro and simplicity since it involves only 4 large vascular anastomoses and 1 duodeno-jejunostomy with no separate biliary anastomosis. This new choledochojejunostomy anastomosis method promotes the postoperative recovery of patients. We used a quadruple immunosuppressive regimen, including basiliximab, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and prednisone acetate (Pred), and gradually transitioned to maintenance therapy with tacrolimus alone. We hope that our center’s experience can provide a reference for the selection and perioperative management of clinical multiorgan transplantation.

Conclusions

Simultaneous classic orthotopic liver, pancreas-duodenum, and heterotopic renal transplantation is a promising therapeutic option for patients with insulin-dependent diabetes combined with end-stage hepatic and renal disease, and our center’s experience can provide a reference for clinical multiorgan transplantation.

Supplementary Data

Vessel reconstruction and anastomosis of the donor and recipient.

Abbreviations

- LPDKT

liver, pancreas-duodenum, and kidney transplantation

- POD

postoperative day

- POM

postoperative month

- MOF

multiple organ failure

- SKPT

simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation

- CLKT

combined liver-kidney transplantation

- SLPT

simultaneous orthotopic liver and heterotopic pancreas-duodenum transplantation

- LT

liver transplantation

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- IDDM

insulin-dependent DM

- ESWL

extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

- MMF

mycophenolate mofetil

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- TBil

total bilirubin

- CRE

creatinine

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- IPTR

International Pancreatic Transplant Registry

- IRI

ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Pred

prednisone acetate.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81401324 and 81770410), the Elite program” specially supported by the China Organ Transplantation Development Foundation (2019JYJH12), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2016A020215048), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Organ Donation and Transplant Immunology (2013A061401007), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A1515011557, 2020A1515010903), and the Guangdong Provincial International Cooperation Base of Science and Technology (Organ Transplantation) (2015B050501002), China

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Yu LX, Liu XY, Xu J, et al. Clinical evaluation of abdominal multiorgan transplantation. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2004;24(2):148–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu J, Yu LX, Deng WF, et al. [Simultaneous liver-pancreas-duodenum transplantation: One case report and review of the literature]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;44(3):157–60. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John PR, Thuluvath PJ. Outcome of liver transplantation in patients with diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. Hepatology. 2001;34(5):889–95. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.29134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng CY, Chen CH, Wu MF, et al. Risk factors in and long-term survival of patients with post-transplantation diabetes mellitus: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4581. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakache R, Merhav H. Rapid en bloc liver-pancreas-kidney procurement: More pancreas with better vascular supply. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(4):755–56. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)00969-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samoylova ML, Borle D, Ravindra KV. Pancreas transplantation: Indications, techniques, and outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99(1):87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang G, Qin W, Yuan J, et al. A 14-year follow-up of a combined liver-pancreas-kidney transplantation: Case report and literature review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:148. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzakis AG, Nunnelley MJ, Tekin A, et al. Liver, pancreas and kidney transplantation for the treatment of Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(2):565–67. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Guo QJ, Cai JZ, et al. Simultaneous liver, pancreas-duodenum and kidney transplantation in a patient with hepatitis B cirrhosis, uremia and insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(45):8104–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i45.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera E, Gupta S, Chavers B, et al. En bloc multiorgan transplant (liver, pancreas, and kidney) for acute liver and renal failure in a patient with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Liver Transpl. 2016;22(3):371–74. doi: 10.1002/lt.24402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caicedo LA, Villegas JI, Serrano O, et al. En-bloc transplant of the liver, kidney and pancreas: Experience from a Latin American transplant center. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:114–18. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.901554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matuszkiewicz-Rowińska J, Wieliczko M, Małyszko J. Renal replacement therapy before, during, and after orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2013;18:248–55. doi: 10.12659/AOT.883929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benzing C, Hau HM, Atanasov G, et al. Outcome and complications of combined liver and pancreas resections: A retrospective analysis. Acta Chir Belg. 2016;116(6):340–45. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2016.1186962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haydon G, Neuberger J. Liver transplantation in cirrhotic patients with diabetes mellitus. Liver Transpl. 2001;7(3):234–37. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.22329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegel AB, Lim EA, Wang S, et al. Diabetes, body mass index, and outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;94(5):539–43. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31825c58ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaber AO, Shokouh-Amiri H, Hathaway DK, et al. Pancreas transplantation with portal venous and enteric drainage eliminates hyperinsulinemia and reduces postoperative complications. Transplant Proc. 1993;25(1 Pt 2):1176–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mekeel KL, Langham MR, Jr, Gonzalez-Perralta R, et al. Combined en bloc liver pancreas transplantation for children with CF. Liver Transpl. 2007;13(3):406–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.21070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trotter JF, Bak TE, Wachs ME, et al. Combined liver-pancreas transplantation in a patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Transplantation. 2000;70(10):1469–71. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200011270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornberg A, Küpper B, Bärthel E, et al. Combined en-bloc liver-pancreas transplantation in patients with liver cirrhosis and insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus. Transplantation. 2009;87(4):542–45. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181949cce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruessner AC, Gruessner RW. Pancreas transplantation of US and Non-US cases from 2005 to 2014 as reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) Rev Diabet Stud. 2016;13(1):35–58. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2016.13.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziaja J, Wullstein C, Woeste G, Bechstein WO. High duodeno-jejunal anastomosis as a safe method of enteric drainage in simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2002;7(3):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amin I, Butler AJ, Defries G, et al. A single-centre experience of Roux-en-Y enteric drainage for pancreas transplantation. Transpl Int. 2017;30(4):410–19. doi: 10.1111/tri.12920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ijtsma AJ, van der Hilst CS, de Boer MT, et al. The clinical relevance of the anhepatic phase during liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(9):1050–55. doi: 10.1002/lt.21791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang XW, Yang J, Wang K, et al. A new anastomosis method for choledochojejunostomy by the way behind antrue pyloricum. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126(24):4633–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang L, Liang LJ, Lai JM. [Determination of the postoperative effect on intestinal structure and myoelectric motility in rabbits: Modified uncut jejunal loop versus Roux-en-Y biliodigestive anastomosis.]]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;46(11):839–42. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller ML, Daniels MD, Wang T, et al. Spontaneous restoration of transplantation tolerance after acute rejection. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7566. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karasu Z, Ozacar T, Akyildiz M, et al. Low-dose hepatitis B immune globulin and higher-dose lamivudine combination to prevent hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Antivir Ther. 2004;9(6):921–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Vessel reconstruction and anastomosis of the donor and recipient.