Abstract

Purpose

The study aimed to determine the prevalence and risk factors of frailty among a Chinese cohort of hemodialysis patients and to assess the degree to which frailty was associated with all-cause mortality.

Participants and Methods

We enrolled a group of older adults (≥60 years old) in a prospective cohort study of cognitive impairment in Chinese patients undergoing hemodialysis (registered in Clinical Trials.gov, ID: NCT03251573). We assessed the prevalence of frailty using Fried’s definition in the Cardiovascular Health Study, then we evaluated the associated risk factors of frailty using multivariate logistic regression analysis. Finally, we assessed the association of frailty and all-cause mortality with multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses.

Results

The prevalence of frailty in these 204 enrolled hemodialysis patients was 72.1%. Patients with frailty were more inclined to have composite abnormal components that included poor physical functioning, exhaustion, low physical activity, and undernutrition. Multivariable logistic regression analysis suggested that increased age, female gender, history of diabetes, longer dialysis vintage, lower Kt/V, lower serum level of albumin concentrations, and increased serum iPTH concentrations were independently associated with frailty. Cox regression analysis indicated that frailty as a dichotomous construct was strongly associated with an increased risk of mortality (HR 6.092, 95% CI 1.886–19.677, P = 0.003) in unadjusted analyses. After adjusting (Model I = no adjusted; II = adjusted for age, gender; III = adjusted for age, gender, history of diabetes; IV = adjusted for all covariates associated at the p ≤ 0.10 level with death in unadjusted analyses, including age, history of diabetes, MoCA<26, single-pool Kt/V, and the levels of albumin and iPTH), the association was slightly affected but observed consistent as before.

Conclusion

Frailty is extremely common and is associated with serious clinical outcomes among older hemodialysis patients. Based on those clinical features of frailty, future studies should focus on exploring effective interventions aimed to prevent or attenuate frailty in the older hemodialysis population.

Keywords: frailty, risk factors, older adult, hemodialysis, mortality

Introduction

Frailty has become an emerging public health problem with the advent of the aging society worldwide, currently, frailty is regarded as a state of vulnerability to poor resolution of homeostasis after a stressor event and is a consequence of a cumulative decline in many physiological systems during a lifetime.1,2 The prevalence of frailty is about 7.0% among community-dwelling aged 60 years or older; and varies with different definitions and increasing age.3,4 Previous studies also indicated that frailty could increase the risk of adverse outcomes among the community-dwelling elders.5,6

As the proportion of older hemodialysis patients kept increasing in recent years, the occurrence of frailty and its influence on the clinical outcomes among those patients also caused great attention.7,8 Johansen and his colleagues examined the prevalence of frailty among 2275 adult hemodialysis patients, and the result showed that nearly one-third of patients on hemodialysis were frail, and frailty was associated with mortality.9 Another cross-sectional analysis from Japan showed that the prevalence of frailty was 21.4% among a group of hemodialysis patients whose average age was 67.2± 11.9 years old, the data also showed that the prevalence of frailty increased steadily with age and was more prevalent in females than in males.10 Currently, there is still limited data concerning the clinical features of frailty and its association with adverse outcomes in Chinese older patients undergoing hemodialysis.

According to the China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET) 2016 Annual Data Report, the number of patients receiving hemodialysis kept increasing in the last 10 years. There were 447,435 patients with end-stage renal disease receiving hemodialysis by the end of 2016 with an average age of 56.1±11.9 years old.11 Finding the significant characteristics of frailty may contribute to the identification of patients at risk for frailty-associated outcomes and consequently design interventions for them to improve functioning or prevent decline. Therefore, we evaluated the prevalence and related risk factors of frailty using the definition of frailty phenotype applied in the Cardiovascular Health Study and examined whether there was an association between frailty and all-cause mortality in a Chinese prospective cohort of older patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study used the data repository from the prospective cohort study of cognitive impairment in Chinese patients undergoing hemodialysis (registered in Clinical Trials.gov, ID: NCT03251573). Potential study participants were 613 maintenance hemodialysis patients recruited from 11 hemodialysis centers in Beijing, who were screened for eligibility between April 2017 and June 2017.12 Patients were excluded if they (1) were younger than 60 years; (2) unwilling to participate in the assessment of frailty; (3) did not fully complete the frailty assessment.

This prospective cohort study was performed on the basis of the guidelines from the Helsinki Declaration and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval no. SJT2016-18). This approved protocol was also authorized by other joining hospitals as a general ethical document. All participants provided written informed consent by themselves or their legal guardians.

Definition of the Frailty Phenotype

We adopted a definition of frailty with components that applied in the Cardiovascular Health Study by Fried et al, each of the five components included in the frailty phenotype was assessed at the study enrollment.4 Weight loss was determined by asking participants whether they had lost more than 10 pounds in the last year unintentionally. To avoid the influence of excess volume load among dialysis patients, we applied the dry weight of patients after the dialysis treatment as the “weight” in evaluating “weight loss” in the questionnaire of Fried’s criteria. Exhaustion was based on questions about endurance and energy from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale.13 Low physical activity was ascertained from the short version of the modified Minnesota Leisure Time Activity (MMLTA) questionnaire, which asks about the frequency and duration of participation in various activities over 2 weeks, using gender-specific cut points.14 Participants performed three tests of grip strength with each hand, and the mean of the strongest hand was used to determine frailty using cutoffs that were developed in the original study of frailty phenotype by Fried and colleagues, which varied according to gender and body mass index. Walking speed was measured while participants walked at their usual pace over a 15-foot course, and the faster of two trials was recorded. (Table 1). Walking speed and hand grip were all measured on the second day of dialysis to avoid the influence of rapid volume change. The trained coordinators of our study interviewed participants, measured physical performance, and administered study questionnaires.

Table 1.

Criteria and Cut Points for Each Component of the Fried Frailty Phenotype

| Component | Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight loss | “In the past 12 months, have you lost more than 10 pounds unintentionally (ie, not due to dieting or exercise)?” | |

| Weakness | Weakness was defined as adjusted mean grip strength in the stronger arm in the lowest 20th percentile of a community-dwelling population of adults aged 60 years and older. | |

| Men: | Women: | |

| BMI ≤ 24 kg/m2: ≤ 29 kg | BMI ≤ 23 kg/m2: ≤ 17 kg | |

| BMI 24.1–26 kg/m2: ≤ 30 kg | BMI 23.1–26 kg/m2: ≤ 17.3 kg | |

| BMI 26.1–28 kg/m2: ≤ 31 kg | BMI 26.1–29 kg/m2: ≤ 18 kg | |

| BMI > 28 kg/m2: ≤ 32 kg | BMI > 29 kg/m2: ≤ 21 kg | |

| Exhaustion | Two items from the CES-D: (1) I felt that everything I did was an effort. (2) I could not get “going.” Patients were asked how often in the last week they felt this way, and those who chose “a moderate amount of the time (3–4 days)” or “most or all of the time (5–7 days)” to either question were considered to meet the exhaustion criterion for frailty. | |

| Low activity | Leisure-time physical activities over the 2 weeks before the study assessment were assessed using the short version of the MLTA Questionnaire. Weekly activities were converted to kilocalories of energy expenditure, and the frailty criterion if individuals were below the 20th percentile of a community-dwelling elderly population based on gender (men, <383 kcal/week; women, <270 kcal/week). | |

| Slow walking speed | Individuals with a walking speed less than the 20th percentile of a community-dwelling elderly population, adjusted for gender and height: | |

| Men: | Women: | |

| Height ≤ 173 cm: ≥ 7 s | Height ≤ 159 cm: ≥ 7 s | |

| Height > 173 cm: ≥ 6 s | Height > 159 cm: ≥ 6 s | |

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Survey-Depression Scale; MLTA, Minnesota Leisure Time Activities.

Participants who met at least 3 criteria were defined as frailty; those who met 1 or 2 criteria were defined as pre-frailty, and those who did not meet any criteria were considered as no frailty.4

Risk Factors Associated with Frailty

To determine the risk factors associated with frailty, we identified a set of factors that we suspected might be associated with frailty and for which data were available in our database. These included demographic factors such as age, gender, marital status, education; comorbidity data such as smoking history, alcohol intake, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease (CHD); the serum levels of hemoglobin, albumin, total cholesterol, triglyceride, phosphate, intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration; body mass index; hemodialysis vintage and adequacy-related variable (the single-pool Kt/V which was calculated from the pre-and post-dialysis serum urea nitrogen levels). In addition, cognitive function assessment was performed under standardized conditions (before dialysis, alone in a separate room, and by trained research staff) using the Chinese Beijing version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-BJ), in which a maximum of 30 points is attainable. The cut-off value for pathological patterns is 26 points.15,16

Study Outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Survival time was defined as the time elapsed from initial study enrollment until death, kidney transplantation, and the end of the one-year follow-up period (June 30, 2018). We obtained the survival status of the patients through periodic medical chart monitoring, as well as contacting each facility in the hemodialysis units.

Statistical Analyses

Participant characteristics at baseline were described according to the degree of frailty. Continuous variables were expressed as mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR); categorical variables were expressed as a number with a percentage. Differences between the groups of normal, pre-frailty, and frailty were compared using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and One-way ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis H-test, as appropriate, for continuous variables. We calculated the frequency of no frailty, pre-frailty, and frailty.

We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to evaluate the predictors related to frailty, with frailty as the dependent variable and 7 variables associated at the p≤0.10 level with frailty in unadjusted analyses as covariates into the multivariate logistic regression models. Survival curves were constructed using Kaplan-Meier estimates with comparisons between curves based on the log-rank χ2 statistic. The effect of frailty on the risk of all-cause mortality was quantified by hazard ratios (HRs; with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) using univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses. In the Cox proportional hazards models, we repeated analyses after adjusting for a set of covariates (model I = unadjusted; II = adjusted for age, gender; III= adjusted for age, gender, history of diabetes; IV = adjusted for all covariates associated at the p≤0.10 level with all-cause mortality in unadjusted analyses). We also performed a sensitivity analysis to validate the relationship between frailty and all-cause mortality by applying frailty components as a continuous variable in the Cox proportional hazards analysis.

Statistical significance was set at a value of p<0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 21.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Frailty Status

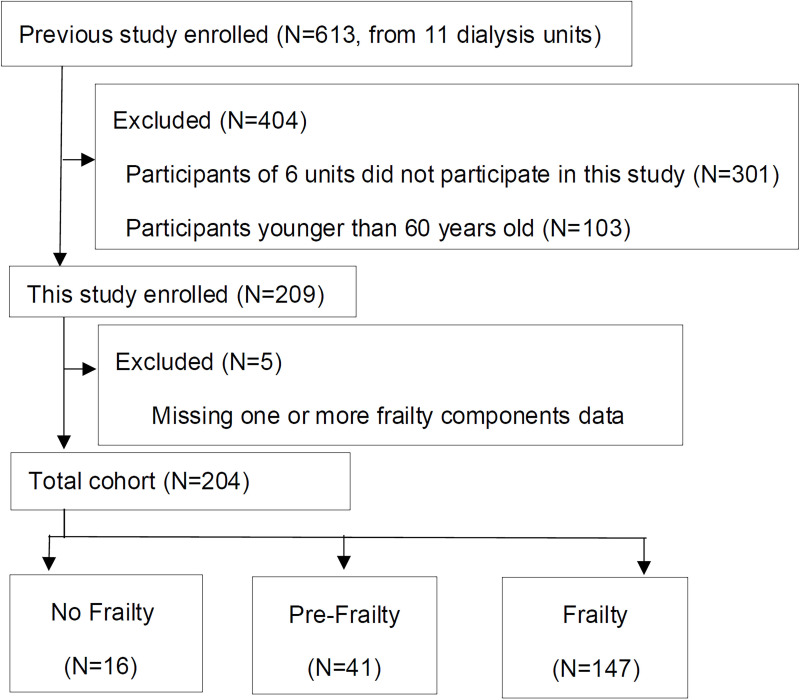

The previous study enrolled 613 patients from 11 dialysis units. Among them, all 301 patients of 6 units did not participate in this frailty assessment, 103 patients were younger than 60 years old, and 5 patients had one or more frailty components data loss. Finally, 204 patients were included in this cohort study with completed frailty assessments data and all the other necessary covariates (Figure 1). Participants’ mean age was 71.65±5.89 years, 44.6% were women and the median dialysis vintage was 59.0 months (71.19±64.74 months). All patients received renal replacement therapy for 12 hours a week, the modalities included hemodialysis and hemofiltration. We used the prescription of glucose-free bicarbonate dialysate with endotoxin less than 0.25EU/mL and used polyacrylonitrile or polycarbonate membrane dialyzer with ultrafiltration rates of 40–55mL/h·mmHg in our patients. The leading etiology of ESRD was diabetic nephropathy. The comparison of basic characteristics between included and excluded patients were illustrated in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram of participants enrolled in this study.

According to Fried’s classification criteria, 16 patients (7.84%) were classified as no frailty, 41 patients (20.10%) as pre-frailty, and 147 patients (72.06%) as frailty. Patients with a higher degree of frailty were older and more likely to have lower education levels, comorbid diabetes, longer dialysis vintage, lower Kt/V, and lower serum albumin concentration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients with Different Frailty Status

| Characteristics | Total (n=204) | Frailty Status | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Frailty (n=16) | Pre-Frailty (n=41) | Frailty (n=147) | |||

| Demographic | |||||

| Age, years | 71.65±5.89 | 68.81±5.29 | 64.80±4.81 | 73.86±4.47 | 0.001 |

| Gender, female | 91(44.6) | 4(25.0) | 15(36.6) | 72(49.0) | 0.096 |

| Married | 183(89.7) | 15(93.8) | 37(90.2) | 131(89.1) | 0.839 |

| Education level | 0.014 | ||||

| Primary school (<6 years) | 12(5.9) | 2(12.5) | 1(2.4) | 10(6.8) | |

| Middle school (6–12 years) | 133(65.2) | 8(50.0) | 21(51.2) | 103(70.1) | |

| Higher education (>12 years) | 59(28.9) | 6(37.5) | 19(46.3) | 34(23.1) | |

| Smoking history | 95(46.6) | 7(43.8) | 21(51.2) | 67(45.6) | 0.792 |

| Alcohol intake | 78(38.2) | 7(43.8) | 20(48.8) | 51(34.7) | 0.233 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | 177(86.8) | 13(81.3) | 34(82.9) | 130(88.4) | 0.537 |

| Diabetes | 84(41.2) | 2(12.5) | 15(36.6) | 67(45.6) | 0.031 |

| Stroke | 31(15.2) | 3(18.8) | 6(14.6) | 22(15.0) | 0.921 |

| CHD | 65(31.9) | 3(18.8) | 11(26.8) | 51(34.7) | 0.318 |

| MoCA<26 | 130(63.7) | 9(56.3) | 30(73.2) | 91(61.9) | 0.336 |

| Dialysis vintage, mo. | 59.00(21.00, 99.50) | 20.00(7.00, 63.50) | 34.00(12.00, 90.00) | 65.00(28.50, 106.00) | 0.005 |

| Single-pool Kt/V | 1.29±0.17 | 1.35±0.15 | 1.34±0.13 | 1.27±0.18 | 0.019 |

| nPCR, g/(kg·d) | 0.98±0.15 | 0.99±0.14 | 0.99±0.11 | 0.98±0.16 | 0.132 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.95±4.28 | 26.18±8.59 | 23.98±3.69 | 23.7±3.68 | 0.089 |

| Laboratory | |||||

| Hb, g/L | 110.24±13.33 | 111.56±15.60 | 111.68±10.29 | 109.69±13.81 | 0.645 |

| Alb, g/L | 37.67±3.35 | 40.84±3.09 | 39.44±3.25 | 36.84±3.02 | 0.000 |

| CPK, U/L | 210.22±23.30 | 221.06±25.00 | 211.76±18.43 | 209.78±21.80 | 0.725 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.22±1.39 | 4.28±0.90 | 4.06±0.82 | 4.26±1.55 | 0.706 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.99±1.22 | 2.28±1.39 | 1.95±1.12 | 1.97±1.23 | 0.611 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.23±0.25 | 2.19±0.17 | 2.20±0.25 | 2.24±0.25 | 0.511 |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 1.73±0.72 | 1.69±0.44 | 1.84±0.77 | 1.71±0.73 | 0.569 |

| iPTH, pg/mL | 164.90(85.33, 270.20) | 116.10(38.66226.25) | 162.80(102.9, 255.50) | 166.30(88.20, 282.55) | 0.287 |

| CRP, mg/L | 2.7(1.31, 5.55) | 1.78(1.14, 4.63) | 2.77(1.26, 5.00) | 2.70(1.39, 5.72) | 0.777 |

| EPO dosage, u/W | 7500(6000,9000) | 9000(6750,9000) | 7500(6000,9000) | 7500(6000,9000) | 0.198 |

Note: Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range: 25th to 75th percentiles] or n (%).

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; Kt/V, an indicator for evaluating dialysis adequacy; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; BMI, body mass index; Hb, hemoglobin; ALB, albumin; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; CRP, C-reactive protein; EPO, erythropoietin.

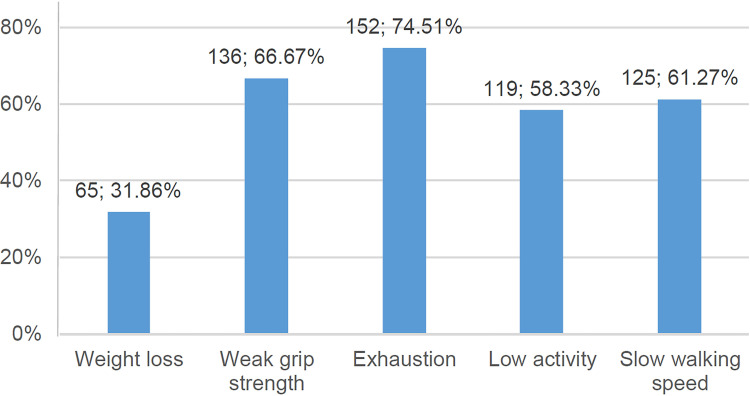

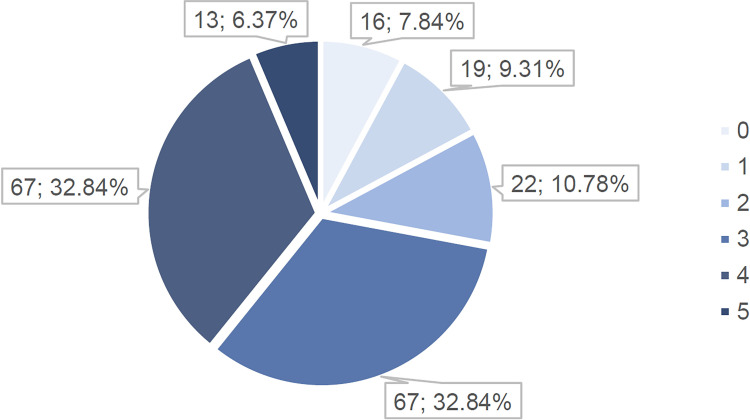

At baseline, 31.86% of the participants met the criterion for unintentional weight loss, 74.51% for exhaustion, and 58.33% for low activity. In addition, 66.67% had weak grip strength and 61.27% had slow walking speed (Figure 2). Furthermore, 7.84%, 9.31%, 10.78%, 32.84%, 32.84%, and6.37% of all patients met 0 to 5 frailty component combinations, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Number and percentage of patients in each frailty component.

Figure 3.

Number and percentage of patients who had 0 to 5 combining frailty component.

Risk Factors Associated with Frailty

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the risk factors independently associated with frailty included increased age (OR=1.393, 95% CI 1.241–1.563, P<0.001), female (HR=1.920, 95% CI 1.014–3.636, P=0.045), history of diabetes (OR=3.610, 95% CI 1.262–10.327, P=0.017), longer dialysis vintage (OR=1.011, 95% CI 1.002–1.020, P=0.019), lower dialysis dosage variable Kt/V (OR=0.711, 95% CI 0.516–0.979, P=0.037), lower serum level of albumin concentrations (OR=0.754, 95% CI 0.644–0.882, P<0.001) and increased serum iPTH concentrations (OR=1.344, 95% CI 1.024–1.763, P=0.033) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Analysis of Predictors for Frailty

| Variables | Adjusted OR* | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.393 | 1.241–1.563 | <0.001 |

| Gender (female) | 1.920 | 1.014–3.636 | 0.045 |

| History of diabetes | 3.610 | 1.262–10.327 | 0.017 |

| Dialysis vintage (per 1-month increase) | 1.011 | 1.002–1.020 | 0.019 |

| Single-pool Kt/V (per 0.1 increase) | 0.711 | 0.516–0.979 | 0.037 |

| ALB (per 1g/L increase) | 0.754 | 0.644–0.882 | <0.001 |

| iPTH (per 100pg/mL increase) | 1.344 | 1.024–1.763 | 0.033 |

Note: All covariates with a P value of less than 0.10 on univariable analysis were entered into the multivariable model, including age, gender, marital status, history of diabetes, dialysis vintage, single-pool Kt/V, and the levels of albumin and iPTH.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Kt/V, an indicator for evaluating dialysis adequacy; ALB, albumin; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone.

Association Between Frailty and All-Cause Mortality

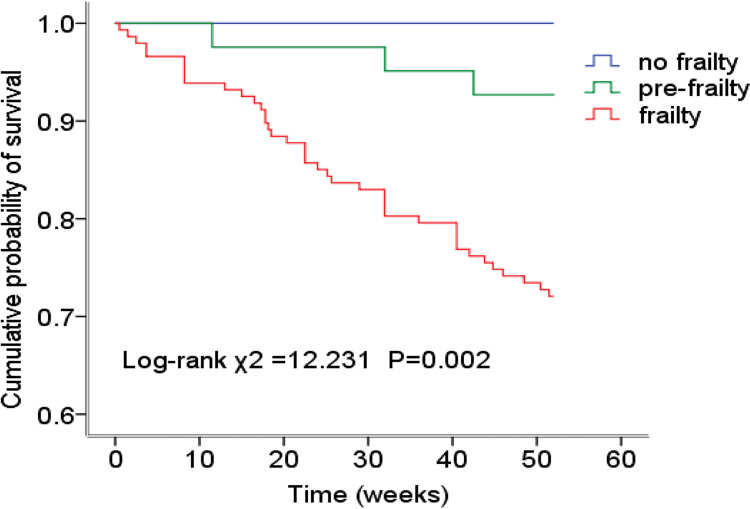

Patients were followed for a median of 52 weeks (46.48±12.45 weeks), and there were 44 deaths during follow-up. The mortality rates were 0% (0/16) for no frail, 3.2% (3/47) for pre-frail, and 9.2% (41/147) for frail patients (P=0.002).

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed a lower cumulative survival rate in the frail group compared with the pre-frail or no frail groups (log-rank χ2=12.231, P=0.002). The pairwise comparison of the three groups using the Log-rank method showed that there were significant differences between the no-frailty group versus the frail group (χ2 =7.256, P=0.007) and the pre-frailty group versus the frail group (χ2 =5.238, P=0.022), but there was no significant difference between the no-frailty group and the pre-frailty group (χ2 =1.200, P=0.273). (Figure 4). Cox regression analysis indicated that frailty as a dichotomous construct was strongly associated with an increased risk of mortality (HR 6.092, 95% CI 1.886–19.677, P=0.003) in unadjusted analyses. After adjusting (Model I = no adjusted; II = adjusted for age, gender; III = adjusted for age, gender, history of diabetes; IV = adjusted for all covariates associated at the p≤0.10 level with death in unadjusted analyses, including age, history of diabetes, MoCA<26, single-pool Kt/V, and the levels of albumin and iPTH), the association was slightly affected but observed consistent as before. (Table 4).

Figure 4.

Time to death. Kaplan-Meier plot of the association between frailty and survival. The pairwise comparison showed that there were significant differences between the frailty group and no frailty group (Log Rank χ2=7.256, P=0.007), frailty group and pre-frailty group (Log Rank χ2=5.238, P=0.022), respectively. No significant difference between the no frailty group and pre-frailty (Log Rank χ2=1.200, P=0.273).

Table 4.

Cox Regression Analyses of All-Cause Mortality Among Participants with Frailty

| Models | Hazard Ratios of All-Cause Mortality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR * | 95% CI | P-value | HR # | 95% CI | P-value | |

| I | 6.092 | 1.886–19.677 | 0.003 | 1.860 | 1.357–2.548 | <0.001 |

| II | 5.107 | 1.414–18.441 | 0.013 | 1.781 | 1.263–2.510 | 0.001 |

| III | 4.451 | 1.224–16.189 | 0.023 | 1.627 | 1.155–2.292 | 0.005 |

| IV | 3.832 | 1.116–13.157 | 0.033 | 1.507 | 1.073–2.118 | 0.018 |

Notes: model I: unadjusted; model II: adjusted for age, gender; model III: adjusted for age, gender, history of diabetes; model IV: adjusted for all covariates associated at the p≤0.10 level with death in unadjusted analyses (including age, history of diabetes, MoCA<26, single-pool Kt/V, and the levels of albumin, iPTH); * Frailty was regarded as a dichotomous variable; # The number of frailty components was regarded as a continuous variable.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Sensitivity analysis showed that the number of frailty components as a continuous variable was still associated with mortality in univariable analyses (HR 3.935, 95% CI 1.153–13.433, P=0.029). After adjustment for all baseline variables, the association was attenuated but remained statistically significant (HR 1.507, 95% CI 1.072–2.117, P=0.018).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we found that the overall prevalence of frailty in the older hemodialysis patients was 72.1%, which was significantly higher than those in community-dwelling older adults in both the United States and China.3,17,18 It increased with age, female gender, history of diabetes, and lower serum of albumin concentrations. Some hemodialysis-related factors like longer dialysis vintage, lower Kt/V, and increased serum iPTH were also associated with the incidence of frailty. After 1 year follow-up, the frailty was found to be associated with all-cause mortality. Facing the great challenge of the rapidly increasing aged dialysis population, our study provided reliable clinical evidence about the clinical significance of frailty and its relationship with adverse outcomes among Chinese hemodialysis patients.

The prevalence of frailty has been reported much higher in the dialysis population.19,20 Johansen et al9 reported that the prevalence of frailty in the incident hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients was 67.7% in the Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study (DMMS) Wave 2. Other reports from Japan and Korea showed that the prevalence of frailty was 21.4% and 34.8%, respectively.10,21 Our study showed that the prevalence frailty among older hemodialysis patients was 72.1%, this result was similar to that in DMMS Wave 2 study and much higher than that in Japan and Korea. This inconsistency seems to be related to the differences in the characteristics of study populations. DMMS Wave 2 study included patients with an average age of 58.2±15.5 years old, while the studies from Korea and Japan include patients with an average age of 55.2±11.9 years old and 67.2±11.9, respectively. Compared with these studies, the average age of the enrolled patients in our study was 71.65±5.89 years old. As the increased age is a closely related factor in the prevalence of frailty, the difference of age among the above-mentioned studies could partially explain the different prevalence of frailty. At the same time, we also noticed that the prevalence of frailty in our study was significantly higher than that in the age-matched studies among the community-dwellings, Fried reported that the prevalence of frailty was 6.9% in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) with a group of older community-dwelling who were ≥60 years old, and the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) cohort with 40,000 women between the ages of 65 and 79 indicated the prevalence of frailty was 16.3%.4,22 This different prevalence of frailty between hemodialysis patients and community-dwellings indicated that the pathological changes of chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis treatment per se might be related to the high prevalence of frailty among those patients. Indeed, proposed mediators of accelerated decline in frailty-related functioning, such as inflammation, oxidative stress are common and often severe in ESRD.23,24 These changes may be major contributors to the development of frailty in hemodialysis patients, understanding those pathological processes might be helpful in reducing the incidence of frailty among them. At the same time, we also noticed the different definitions of frailty might be another major issue that could influence the prevalence of frailty, currently, Fried’s criteria, Wood’s criteria, and DMMS Wave 2 criteria are 3 main definitions applied in the previous studies.9 The difference of these criteria might be one of the important reasons for the difference in the prevalence of frailty.

Identifying the frailty associated risk factors is an important step in the prevention of frailty, our results showed that older age, female, comorbidity of diabetes, lower serum of albumin concentrations were associated with the prevalence of frailty, these factors were also found in other frailty studies of the general population and dialysis patients.7,17,23 Besides these factors, Johansen et al9 also showed that hemodialysis modality was a significant predictor of frailty, but they did not analyze the detailed variables of dialysis modality. In our study, we found that longer dialysis vintage, lower Kt/V, and a higher level of serum iPTH were also associated with the incidence of frailty. Keeping improving the quality of hemodialysis treatment could potentially improve these dialysis-related variables and might become the potential measure in reducing the prevalence of frailty among dialysis patients.19,25 These confirmed hemodialysis-related risk factors also remind us that we should make more accurate interventions in frailty prevention among hemodialysis patients.

As a multidimensional construct reflecting the decline in health and functioning in the elderly, frailty ultimately increased the risk for disability, hospitalization, and death.23 This association has been widely examined among community-dwelling and hemodialysis patients.26 In the CHS, the 3-year all-cause mortality was increased to 1.5 folds in the frailty population compared with that in non-frailty individuals.4 In the DMMS Wave 2 study, the Kaplan-Meier plots and the hazard ratio of 1-year all-cause death indicated the death rate increased significantly in the hemodialysis patients with frailty.9 In our study, the Kaplan-Meier curves indicated that the survival rate in the frailty group was significantly lower than that in the pre-frailty and no-frailty group, Cox regression analysis showed that all-cause mortality was increased to 3.9 folds in frailty dialysis patients compared with that in non-frailty patients. Our data, together with previous results provided enough evidence about the relationship between frailty and adverse outcomes. It seems urgent to make identification and prevention of frailty among elderly populations.

The study also has several limitations. First, we enrolled the patients whose age was ≥ 60 years old, and the average age was more than 70 years old, the results could only reflect the high prevalence of frailty of the patients in this age group, and might have an overestimation of the prevalence of frailty among the Chinese hemodialysis patients, we are preparing to explore this issue in another age group of dialysis patients. Second, as the frailty could change with time, it would be meaningful to evaluate frailty longitudinally in dialysis patients so that the cumulative effects of dialysis therapy on frailty could be examined. Third, some blood samples were not taken which would have been informative to explore associations among frailty, inflammation, oxidative stress. Even with those limitations, our study still has several strengths. First, we applied Fried’s definition of frailty in CHS, which included more precise measures of actual physical performance compared with that other definition with a self-reported questionnaire. Second, the comorbid conditions and laboratory data were also assessed by qualified staff after a review of medical charts. Third, the associations among frailty and mortality were determined using multivariable methods to adjust for the possible confounding.

Conclusion

We described an extremely high prevalence of frailty in a group of Chinese older patients undergoing hemodialysis. The frailty among those patients was significantly associated with all-cause mortality. Apart from some of the classical risk factors like increased age, female, diabetes, and lower level of serum albumin, three hemodialysis-related factors including dialysis vintage, single-pool Kt/V, and iPTH were found to be associated with the prevalence of frailty. Interventions aimed at delaying the development of frailty should pay more attention to adjusting the dosage of dialysis and controlling the complications of hemodialysis in those dialysis patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged the tremendous assistance of the doctors and nurses in the dialysis centers at 11 hospitals in Beijing for their support and collaboration in this research.

Funding Statement

This project was supported by grants from The Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z161100002616005) and The capital health research and development of special (2022-2-2081). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

The raw data supporting the findings of this study will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement and Informed Consent

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval no. SJT2016-18), this approved protocol was also authorized by other joining hospitals as a general ethical document. All participants provided written informed consent by themselves or their legal guardians.

Consent for Publication

The authors obtained written informed consent to publish the participant’s related details in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crocker TF, Clegg A, Riley RD, et al. Community-based complex interventions to sustain Independence in older people, stratified by frailty: a protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e045637. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt J, Long S, Carter B, Bach S, McCarthy K, Clegg A. The prevalence of frailty and its association with clinical outcomes in general surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018;47(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JC, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD. Frailty and protein-energy wasting in elderly patients with end stage kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(3):337–351. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012010047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng JK, Kwan BC, Chow KM, et al. Frailty in Chinese Peritoneal Dialysis Patients: prevalence and Prognostic Significance. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2016;41(6):736–745. doi: 10.1159/000450563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2960–2967. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi H, Uchida HA, Kakio Y, et al. The Prevalence of Frailty and its Associated Factors in Japanese Hemodialysis Patients. Aging Dis. 2018;9(2):192–207. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C, Gao B, Zhao X, et al. Executive summary for China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET) 2016 Annual Data Report. Kidney Int. 2020;98(6):1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo Y, Murray AM, Guo YD, et al. Cognitive impairment and associated risk factors in older adult hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12542. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69482-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42(1):28–33. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(12):741–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu J, Li D, Li F, et al. Montreal cognitive assessment in detecting cognitive impairment in Chinese elderly individuals: a population-based study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2011;24(4):184–190. doi: 10.1177/0891988711422528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian R, Guo Y, Ye P, Zhang C, Luo Y. The validation of the Beijing version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in Chinese patients undergoing hemodialysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siriwardhana DD, Hardoon S, Rait G, Weerasinghe MC, Walters KR. Prevalence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018195. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu W, Li YX, Wu C. Incidence of frailty among community-dwelling older adults: a nationally representative profile in China. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):378. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1393-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez-Agudelo SY, Musso CG, González-Torres HJ, et al. Optimizing dialysis dose in the context of frailty: an exploratory study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53(5):1025–1031. doi: 10.1007/s11255-020-02757-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos D, Pallone JM, Manzini C, Zazzetta MS, Orlandi FS. Relationship between frailty, social support and family functionality of hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2021;139(6):570–575. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2021.0089.R1.0904221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SY, Yang DH, Hwang E, et al. The Prevalence, Association, and Clinical Outcomes of Frailty in Maintenance Dialysis Patients. J Ren Nutr. 2017;27(2):106–112. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, et al. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1321–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury R, Peel NM, Krosch M, Hubbard RE. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;68:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(9):505–522. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0064-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang SH, Do JY, Lee SY, Kim JC. Effect of dialysis modality on frailty phenotype, disability, and health-related quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Glidden D, et al. Association of Performance-Based and Self-Reported Function-Based Definitions of Frailty with Mortality among Patients Receiving Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(4):626–632. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03710415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]