Abstract

The presence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) bearing mutations resistant to nucleosidic inhibitors of the viral reverse transcriptase (RT) derived from HIV-seropositive asymptomatic and untreated volunteer blood donors was examined. The RT amplicons of 32 specimens were analyzed by using a reverse hybridization line probe assay technique that detects resistance against zidovudine (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine [AZT], didanosine (2′,3′-dideoxyinosine [ddI], zalcitabine (2′,3′-dideoxycytidine [ddC]), and lamivudine {(−)-β-l-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine [3TC]} at amino acid positions 41, 69, 70, 74, 184, and 215 of the HIV RT. One sample (brp004, subtype B) showed an AZT resistance secondary mutation at position K70R. Fifteen specimens revealed one or more sites of nonreactivity to both wild-type- and mutant-specific probes (dual nonreactivity). Samples were also submitted to RT direct sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. Nine of 32 specimens belonged to non-B subtypes (C, D, F, and F/B or B/F mosaics). Three of these non-B isolates, named brp004, brp063, and brp069, revealed three other relevant AZT resistance mutations—a T215F mutation and two M41L mutations, respectively—hidden by the nonreactivity to line probe assay strips on the respective codon regions. The isolate brp004 also carried a D67N AZT resistance mutation revealed by direct sequencing. No nonnucleosidic RT inhibitor-resistant mutation was found. The analysis revealed a frequency of 2.26 × 10−4 mutations per nucleotide for independent samples related to RT resistance. These findings emphasize the magnitude of naturally occurring reservoirs of drug-resistant virus among untreated HIV-1-positive individuals in Brazil.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is the etiologic agent of the AIDS pandemic. The prevalence of HIV-1 in Brazil is the highest in Latin America, with 110,000 cases of AIDS cumulatively reported by the National Health Agencies in 1996 (13). The genetic diversity of HIV-1 strains circulating in this country includes not only the prevalent HIV-1 subtype B found in the United States and other developed countries (10, 15, 19, 20), but also subtypes (15, 20) and C (24); B/F and B/C recombinants (4, 21); and F/B, F/D, and B/C dual infections (10).

The antiretroviral strategies adopted for asymptomatic subjects in Brazil are based on nucleosidic inhibitors of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT), such as zidovudine (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine [AZT]), didanosine (2′,3′-dideoxyinosine [ddI]), zalcitabine (2′,3′-dideoxycytidine [ddC]), lamivudine {(−)-β-l-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine [3TC]) and stavudine (2′,3′-didehydro-3′-deoxythymidine [d4T]). However, concerns have been raised regarding the existence and possible emergence of drug-resistant virus reservoirs naturally occurring within the wide range of HIV-1 Brazilian variants. More information about RT gene mutations causing resistance to nucleosidic inhibitors is needed. The reverse hybridization line probe assay (Inno-LiPA HIV RT; Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium) is designed for the rapid and simultaneous characterization of the most frequent and important drug-selected mutations found in the RT gene, such as those leading to changes in amino acid positions 41, 69, 70, 74, 184, and 215 of the protein (22). This method proved to be useful in studying genetic resistance in follow-up samples of treated HIV-1-infected individuals. Since the resistant RT genotyping assay is designed for the detection of type B HIV genotypes, one may expect some degree of nonreactivity for the RT genotyping assay due to the intrinsic genetic difference between B and non-B HIV subtypes (1), such as those found in Brazil.

Naturally occurring resistance mutations on the RT of HIV variants in untreated seropositive individuals from Brazil are described herein. Also, nucleotide mutations in the RT genes of some samples were found with low specificity for each set of probes scanning the amino acid positions detected by the reverse hybridization line probe assay. They were characterized by phylogenetic analysis and clustered with non-B HIV variants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasma sample collection.

Thirty-two whole-blood samples were collected from January through December 1996 at blood banks distributed throughout the states of Rio de Janeiro and Rio Grande do Sul (2 blood units) and were delivered to the Instituto Noel Nutels, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Plasma samples from collected specimens were stored at −80°C until use. The plasma specimens repeatedly reactive for antibodies to HIV by different commercially available enzyme immunoassays were selected after confirmation of seropositivity with indirect immunofluorescence and Western blot tests (23). These samples were identified by the Brazilian blood bank protocol as being blood specimens from HIV-seropositive asymptomatic and untreated volunteer blood donors identified during 1996. Genetic variation and results of phylogenetic analyses among specimens had previously been used to evaluate the p24gag, C2V3env, and gp41env HIV-1 regions (23).

HIV RNA preparation, cDNA synthesis, and PCR.

HIV RNA preparation and cDNA synthesis were performed as described before (22). In brief, 50 μl of plasma was mixed with 150 μl of guanidinium-phenol (Trizol; Gibco BRL). After lysis and denaturation, a chloroform extraction was made to obtain phase separation; nucleic acids were precipitated from the aqueous phase with isopropanol and were collected by centrifugation. The RNA pellet was dissolved in a random primer solution [pd(N6); Pharmacia]. The synthesis of cDNA occurred in the presence of avian myeloblastosis virus RT (Stratagene) at 42°C. For the nested amplification of the HIV RT gene, a mixture was created that contained 5 μl of cDNA (or 2 μl of the outer PCR product), 5 μl of 10× Taq buffer, 5 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 solution, 1 μl of 10 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μl (25 pmol) of each PCR primer, 31.5 μl of H2O (or 34.5 μl, for the nested reaction), and 0.5 μl (2.5 U) of AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). For both outer and nested-PCR rounds, 35 cycles were performed, with an annealing temperature of 57°C, extension at 72°C, and denaturation at 94°C, over 30 s each. Nested-PCR products were analyzed on agarose gels, and only clearly visible amplification products were used in the Inno-LiPA HIV RT procedure or were purified by using the QIAamp PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Inc.) for further direct sequencing. The following PCR primers were used for sequencing: outer PCR sense primer RT-9 (5′-GTACAGTATTAGTAGGACCTACACCTGTC-3′) and outer PCR antisense primer RT-12 (5′-ATCAGGATGGAGTTCATAACCCATCCA-3′) and nested-PCR sense primer RT-1 (5′-CCAAAAGTTAAACAATGGCCATTGACAGA-3′) and nested-PCR antisense primer RT-4 (5′-AGTTCATAACCCATCCAAAG-3′). The sets of primers used for the Inno-LiPA HIV RT assay were biotinylated at the 5′ end. The RT-1 and RT-4 inner primers provide a PCR fragment (amplicon) of 576 bp, covering the RT coding sequence from amino acid 29 to amino acid 220 (nucleotides [nt] 85 to 660) of the RT coding region, in the clade B isolate HXB2. Primers RT-1 and RT-4 were used for direct sequencing of purified amplicons on their two complementary strands.

Reverse hybridization line probe assay (Inno-LiPA).

Amplification products of PCR-positive samples were hybridized on the line probe assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Innogenetics). Samples were selected for reamplification and direct sequencing when their Inno-LiPA HIV RT strips presented at least one resistance mutation or when no hybridization was revealed to the probe set of at least one of the amino acid positions responsible for HIV RT resistance covered by the assay.

DNA sequencing.

Both strands of the HIV RT gene were sequenced by using the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer-Applied Biosystems) with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase and by following the manufacturer’s protocol. The sequencing reaction mixture was fractionated and analyzed with an automated sequencer (ABI PRISM model 310; Perkin-Elmer-Applied Biosystems). Direct sequencing of PCR-amplified fragments represents a consensus sequence or the dominant viral species present in the plasma.

Sequence analysis.

Sequence data were analyzed by using DNASIS for Windows, version 2.1, software (Hitachi). For subtype determination, nucleic acid sequences were trimmed to equivalent lengths (571 nt) and aligned with RT sequences representative of the HIV-1 group M subtypes A through F available in the Los Alamos database (16) and GenBank database accessed by the web site of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Md.). Alignments were generated by using the same software described before and manually edited. Phylogenetic analysis was performed by using the PHYLIP software package (University of Washington, Seattle) (6). Evolutionary distances were estimated by using DNADIST (Kimura two-parameter method), and phylogenetic relationships were determined using NEIGHBOR (neighbor-joining method). Reproducibility of branching patterns was done with SEQBOOT (bootstrap method; 100 replicates), and the consensus tree was generated with CONSENSE. The sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus of chimpanzees (SIVcpz) RT was used as the out-group.

RESULTS

Analysis of samples by the line probe assay (Inno-LiPA HIV RT).

Thirty-two plasma samples from HIV-seropositive asymptomatic and untreated volunteer blood donors were identified as shown in column 1 of Table 1. All samples used were subtyped by gag and env genotyping (23). The results obtained with the Inno-LiPA HIV RT hybridizations are presented in Table 1. One of the 32 specimens showed a resistance profile (specimen brp004 [Table 1]), and a K70R AZT resistance mutation was revealed. Fifteen specimens showed no reactivity for one or more sets of probes. The current Inno-LiPA HIV RT assay was primarily developed for the detection of RT resistance in HIV genotype B viruses. Considering each relevant amino acid position analyzed by the assay as showing possible reactivity, only 6 of 115 (3.9%) positions of HIV B genotype isolates were not detected. In the non-B isolates, 62.2% of the relevant positions could still be detected. In the overall population tested, a reactivity rate of 85.6% was achieved.

TABLE 1.

Hybridization profile of LiPA strips for RT amplicons of each plasma sample

| Sample identification for genotypea | Result for amino acid position on LiPA stripc:

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlb

|

41

|

69 and 70

|

74 and 75

|

184

|

214 and 215

|

|||||||||||||||

| Conjugate | Amplified (HIV) | M41 | L41 (TTG) | L41 (CTG) | T69K70 | T69R70 | D69K70 | D69R70 | N69R70 | L74V75 | V74V75 | M184 | V184 | F214T215 | L214T215 | T215 | F214Y215 | L214Y215 | F214F215 | |

| B | ||||||||||||||||||||

| brp004 | + | + | + | − | − | − | +** | − | − | +** | + | − | + | − | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* |

| brp009 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp011 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp015 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp019 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp025 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp029 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp030 | + | + | + | − | − | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp043 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp044 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp066 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | |

| brp071 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp075 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp081 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| brp088 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp089 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp093 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | −* | −* | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| brp095 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp105 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp116 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp124 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| brp130 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* |

| brp132 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| C | ||||||||||||||||||||

| brp134 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| brp136 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | + | − | −* | −* | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| D | ||||||||||||||||||||

| brp072 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| E | ||||||||||||||||||||

| brp026 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| brp034 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| brp035 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | − | −* | −* | −* | −* | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| brp127 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| B/F (gag/env) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| brp063 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | − | −* | −* | + | − | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* | −* |

| brp069 | + | + | −* | −* | −* | + | − | − | − | − | −* | −* | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

Sample identification numbers were grouped according to their subtypes established by gag/env genotyping.

Internal controls of the strips.

The relevant codon position analyzed for mutation in each set of probes is shown. +, reactivity of the material analyzed; −, no reactivity; ∗∗, reactivity for drug resistance mutations; *, lack of reactivity for any probe of the relevant codon position analyzed.

Phylogenetic analysis based on RT sequence.

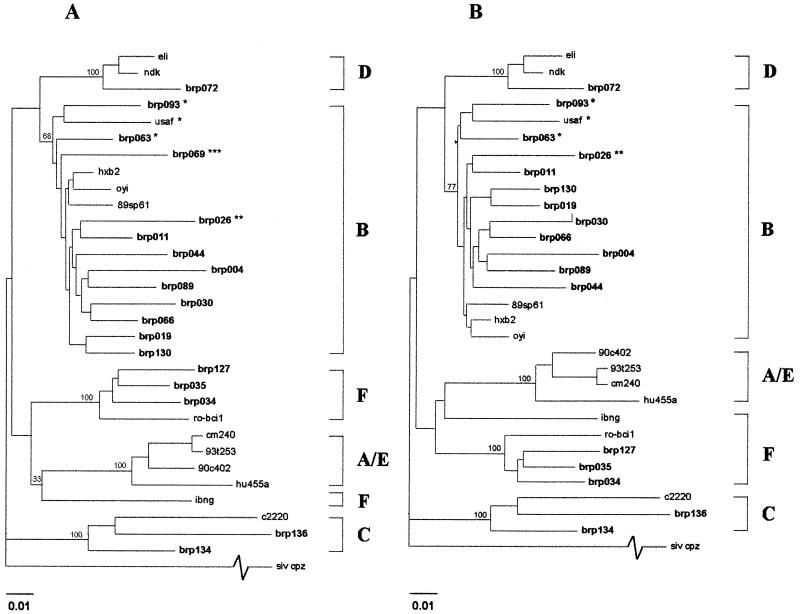

The 15 RT amplicons showing no reactivity for at least one position of the Inno-LiPA HIV RT were sequenced for nucleotide alignment and generation of phenograms (Fig. 1). Three amplicons of Inno-LiPA HIV RT-reactive, nonmutated and B-subtype-defined specimens (brp011, brp019, and brp044) were also sequenced and submitted for phylogenetic analysis.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the pol RT genes of 18 HIV isolates from Brazilian blood donors (A) compared to reference HIV-1 group M subtypes available in the Los Alamos database. Fragments containing a 571-nt region of the HIV RT gene were aligned for the generation of the phenogram. (B) The phenogram was performed without the alignment of the brp069 recombinant sequence. The RT sequence of SIVcpz was used as an outgroup, and bootstrap values for 100 replicates are listed at the major subtype branches. The brazilian isolates sequenced in this study are highlighted. Specimens of mixed subtype are designated as follows: ∗, type B/F mosaics (RT intragenic mosaic and/or p24gag gp41env mosaic); ∗∗, brp026 type B/F/B mosaic (p24gag/pol RT/gp41env gp41); ∗∗∗, brp069 type B/F/B intragenic RT chimera and type B/F p24gag/gp41env mosaic. The hash mark on SIVcpz indicates a truncation of actual distance.

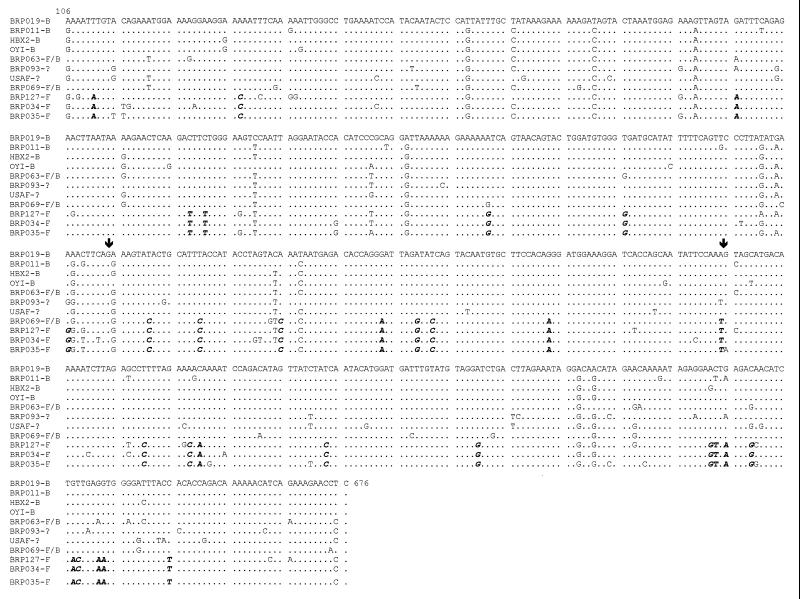

The specimens brp026, brp069, and brp093 were the mosaic exceptions to the prototypic specimens’ phylogenetic distribution (Fig. 1A). Specimen brp026 grouped with the B subtype, revealing a new genotyping for RT different from that described for its gag and env regions (23). The specimens brp063 and brp069 had been described before as mosaic B/F intergenic (gag/env) genomes (23). They grouped with brp093 and USAF, an HIV-1 specimen from the United States described as a unique F subtype-like virus (8) isolated after the patient’s long exposure to nucleosidic RT inhibitors during treatment. Surprisingly, brp069 RT sequence was displayed like a putative intragenic (RT) B/F/B chimera, as shown by complete RT sequence alignment with the subtype B sequences of HXB2 and brp019 and subtype F sequences brp034, brp035, and brp127 (Fig. 2). The alignment clearly reveals the switch of the molecular signature of the RT coding sequence from nt 376 to nt 485. The phenogram of Fig. 1B reveals an increase in the bootstrap value for the genotype B group when the chimeric sample brp069 is excluded from the phylogenetic analysis.

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of the RT gene (nt 106 to 676) of Brazilian specimens brp019 brp011 (subtype B); brp063 and brp093 (subtype B/F mosaics); brp069 (subtype B/F/B chimera); and brp034, brp035, and brp127 (subtype F). The prototypes HXB2 and OYI (subtype B) were also included, as well as the mosaic B/F sequence USAF, which was from an HIV isolate from an American subject undergoing antiretroviral treatment. The dots represent similarity of sequence; the arrows indicate the regions near the putative recombination sites at the brp069 RT gene. The highlighted and italicized bases represent the subtype F sequence signature found.

Sequence alignment of the codons analyzed by Inno-LiPA HIV RT.

Sequence alignments were performed with the prototypic HXB2 RT region as a consensus sequence (Table 2). Sequences of both the mutated and double-blind nonreactive specimens were aligned for each set of codons analyzed in the LiPA assay. Three AZT-resistant mutations were found: one of these was in specimen brp004 (T215F), and the two others occurred on the mosaic B/F specimens brp063 and brp069 (both carrying M41L). The resistant variants were masked by other mutations on the same analyzed region, disabling the hybridization with the Inno-LiPA HIV RT probes.

TABLE 2.

HIV-1 RT gene variability of samples analyzed for codon positions covered by the probes of the LiPA strips

| Genotype | Sample | Sequence for codonsa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38–43

|

68–72

|

72–77

|

|||||

| Nucleic acid | aab | Nucleic acid | aa | Nucleic acid | aa | ||

| B | HXB2 RTc | TGTACAGAGATGGAAAAG | CTEMEK | AGTACTAAATGGAGA | STKWR | AGAAAATTAGTAGATTTC | RKLVDF |

| B | LiPA consensusd | ........A......... | ...... | ............... | ..... | .................. | ...... |

| B | brp044 | ........A......... | ...... | ............... | ..... | ...........G...... | ...... |

| B | brp011 | ........A......... | ...... | ............... | ..... | .................T | ...... |

| B | brp019 | ........A......... | ...... | ............... | ..... | .....G............ | ...... |

| B | brp030 | ........A......... | ...... | .....C......... | ..... | ............A..... | ....N. |

| B | brp004 | ........A......... | ...... | .......g....... | ..R.. | .................. | ...... |

| B | brp130 | ..C.....A......... | ...... | ............... | ..... | ............A..... | ....N. |

| B | brp066 | ........A......... | ...... | ............... | ..... | ............A..... | ....N. |

| B | brp093 | ...G....A......... | .A.... | ..............G | ..... | ..G.........A..... | ....N. |

| F? | brp026 | ........A........A | ...... | ............... | ..... | ............A..... | ....N. |

| B | brp089 | ........A.....G... | ...... | ............... | ..... | ...........G...... | ...... |

| B/F(gag/env) | brp063 | ........At......G. | ...L.R | ............... | ..... | .........T..A..... | ...LN. |

| B/F(gag/env) | brp069 | ......A.At........ | ...L.. | ............... | ..... | .........T..A..... | ...LN. |

| D | brp072 | ........T......... | ..D... | .....C..G...... | ..... | ............A..... | ....N. |

| C | brp134 | ...GAT..A.......G. | .D...R | ........T...... | ..N.. | ............... | ...... |

| C | brp136 | ...CAG..A......... | .E.... | ........T....A. | ..N.K | ............A..... | ....N. |

| F | brp035 | ...TT...A......... | .L.... | ..............G | ..... | ..G.........A..... | ....N. |

| F | brp034 | ....TG..A........A | .M.... | ............... | ..... | ............A..... | ....N. |

| F | brp127 | ........A......... | ...... | ..............G | ..... | ..G.........A..... | ....N. |

| Sequence for codonsa:

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 182–185

|

212–218

|

||

| Nucleic acid | aa | Nucleic acid | aa |

| CAATACATGGAT | QYMD | TGGGGACTTACCACACCAGAC | WGLTTPD |

| ............ | .... | ......T.............. | ..F.... |

| ............ | .... | ......T.............. | ..F.... |

| ............ | .... | ......T.............. | ..F.... |

| ............ | .... | ......T.............. | ..F.... |

| ............ | .... | .....TA.....G........ | ..I.A.. |

| ............ | .... | ......T..tt.T........ | ..FFS.. |

| ............ | .... | .....G......G........ | ....A.. |

| ............ | .... | ........A...T........ | ....S.. |

| ............ | .... | ......T.....C........ | ..F.P.. |

| ............ | .... | ......T.............T | ..F.... |

| ............ | .... | ......T.....T........ | ..F.S.. |

| ............ | .... | ...A................. | .R.... |

| ............ | .... | .....GT.......C...... | ..F.... |

| ........... | .... | ......T.....G.......T | ..F.A.. |

| ............ | .... | ........C............ | ....... |

| .....T...... | .... | ........C............ | ....... |

| .C.......... | P... | ......T....T......... | ..F.... |

| ............ | .... | ......T....T......... | ..F.... |

| ............ | .... | ......T....T......... | ..F.... |

aa, amino acids.

Dots represent matches of nucleotide and amino acids with HXB2 sequences; boldface letters indicate nucleotide and amino acid mutations possibly involved with lack of LiPA reactivity; boldface and italicized letters represent drug resisted mutations.

M group sequence (subtype B) used to align the sample sequences.

The nucleotide consensus presented does not provide the exact probe sequences, but only the regions that represent the required specificity motifs indicated by the consensus amino acids for each region analyzed.

A fourth AZT resistance mutation (secondary mutation), D67N, was found again within the brp004 isolate RT sequence, but was not related to the Inno-LiPA HIV RT genotyping method.

These disabling nucleotide substitutions were responsible for all samples with sites of dual nonreactivity, including those not carrying relevant RT resistance mutations within the double-blind nonreactive region.

In terms of nucleotides, all double-blind nonreactive samples for codon positions 38 to 43 (nt 112 to 129) were found on non-B specimens (except for brp089). The substitutions of subtypes F and C responsible for the lack of reactivity were dinucleotide changes at positions 115 to 116 or 116 to 117. Specimen brp072, the only representative of subtype D, showed sites of dual nonreactivity caused by a G- or A→T transversion at nt 120, while all mosaics and brp089 seemed to be nonreactive due to a melting temperature decrease caused by the double substitutions. For the brp063 B/F mosaic and brp069 B/F/B chimera, one of these two mutations generated the L41-resistant codon.

For codon positions 68 to 72 (nt 202 to 216), a transition mutation was responsible for the double-blind reactive specimen profile (T→C at nt 207 for brp030 and brp072 and G→A at nt 215 for brp134).

Two nucleotide changes along the codon positions 72 to 77 (nt 214 to 231) were found correlating with the double-blind nonreactive phenotype of specimens brp035 and brp127 (subtype F) and brp093, brp063, and brp069.

The codon positions 182 to 185 (nt 544 to 555) presented only two mutated sites, a transition (C→T) at position 549 of specimen brp136 (subtype C) and a transversion (A→C) at position 545 of specimen brp035 (subtype F). Four double-blind nonreactive specimens could be found for codon positions 212 to 218 (nt 634 to 654). Most of them belonged to subtype B (brp004, brp066, and brp130) and presented at least two hybridization-disabling substitutions each. The changes varied between nt 639 to 646, the only exception being a double-blind nonreactive substitution (G→A transversion) at position 637 presented by the mosaic brp063.

Analysis of resistant HIV-1 genotypes based on RT sequence.

Together with the 15 samples previously analyzed by direct amplified cDNA sequencing, the other 17 specimens had their RT amplicons sequenced. All of those 17 samples belonged to the subtype B clade (data not shown), as expected by previous findings (23). No mutation related to resistance to nonnucleosidic RT inhibitors was found in any of these 17 isolates nor in any of the 15 previously sequenced isolates. Also, no other AZT resistance or nucleosidic inhibitor resistance mutation was found within this group of clade B sequences.

DISCUSSION

The natural occurrence of drug resistance mutations in the pol gene of HIV-1 isolates from untreated patients has been reported (5, 12, 14, 17). In some cases, mutations related to RT resistance to ddC and d4T were reported in patients undergoing AZT monotherapy (2, 18). Also, several substitutions on the RT sequence related to the resistance phenotype were found in patients undergoing no drug therapy with a frequency very similar to the average mutation frequencies observed along the pol gene (17), revealing the randomized origin of these substitutions and the importance of the HIV-1 quasispecies reservoir for the occurrence of drug-resistant phenotypes. The analysis of the Brazilian untreated HIV-1-positive individuals studied here revealed a frequency of 2.26 × 10−4 mutations per nucleotide for independent samples related to drug resistance, or 9.38% (3 of 32) of patient specimens presenting drug-resistant mutations. All of these naturally occurring mutations were related to resistance to AZT (1 K70R, 2 M41L, and 1 T215F; 4 of 160 or 2.5% of Inno-LiPA HIV RT positions analyzed, as well as 1 D67N). This finding surpasses the hypothesis of the natural occurrence of these mutations as a result of the quasispecies sequence variation in viral reservoirs (9). The detection of only AZT resistance mutations in the overall naive individuals analyzed may reflect a selective advantage of the AZT-resistant viruses existing in the reservoir of circulating viruses in Brazil, due to the extensive use of this drug during a long period in this country. These AZT-resistant viruses were probably created as a result of the RT error rate that defines the HIV quasispecies, but they were transmitted by AZT-treated individuals to the naive individuals studied here. This implies a positive selective pressure applied to the quasispecies reservoir during AZT treatment. This could explain the coexistence of different D67N, K70R, and T215F AZT resistance mutations in the viral population of a single sample (brp004) of an untreated individual.

The T215F mutation found within sample brp004, as well as K70R, is categorized as primary mutation, i.e., is selected early in the process of resistance mutation accumulation and may have a discernible inhibitor-specific effect on virus drug susceptibility (9). The M41L mutations found, on the other hand, are considered secondary mutations, with no discernible effect on magnitude of resistance when found alone, but selected because they improve viral fitness. The results confirm the importance of keeping the patient’s viral load down-regulated in order to substantially decrease its capacity to replicate and, thus, its ability to transform even into a drug resistance phenotype under weak drug pressure (3, 7, 11, 25).

Using the line probe assay (Inno-LiPA), a number of sites of dual nonreactivity of non-B subtypes were detected (17 of 45 positions [37.8%]). Most such cases were not of significance for resistance genotyping and generally originated by one or few substitutions not relevant at the nucleotide level. Nevertheless, three relevant resistance mutations related to the Inno-LiPA HIV RT positions analyzed were attributed to the B/F chimeric specimens brp063 and brp069 (2 of 45 [4.4%]) and B specimen brp004 (1 of 115 [0.9%]) and were masked by the double-blind reactivity of the Inno-LiPA strips.

This work describes the drug-resistant mutations found in the viral populations of untreated HIV-1-infected individuals from Brazil, probably as a result of the high degree of genetic variability for this virus. This leads to the appearance of HIV-1 subpopulations with the resistant genotypes that represent a reservoir of virus capable of infective spreading and causing therapeutic failure during treatment. This finding poses an important concern for antiretroviral therapy in Brazil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apetrei C, Loussert-Ajaka I, Descamps D, Damond F, Saragosti S, Brun-Vezinet F, Simon F. Lack of screening test sensitivity during HIV-1 non-subtype B seroconversions. AIDS. 1996;10:F57–F60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199612000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brun-Vézinet F, Boucher C, Loveday C, Descamps D, Fauveau V, Izopet J, Jeffries D, Koye S, Krzyanowski C, Nunn A, Schuurman R, Seigneurin J M, Tamalet C, Tedder R, Weber J, Weverling G J. HIV-1 viral load, phenotype, and resistance in a subset of drug naive participants from the Delta trial. The National Virology Groups. Delta Virology Working Group and Coordinating Committee. Lancet. 1997;350:983–990. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)03380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffin J M. HIV-1 population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornelissen M, Kampinga G, Zorgdrager F, Goudsmit J the UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes defined by env show high frequency of recombinant gag genes. J Virol. 1996;70:8209–8212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8209-8212.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornelissen M, van den Burg R, Zorgdrager F, Lukashov V, Goudsmit J. pol gene diversity of five human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes: evidence for naturally occurring mutations that contribute to drug resistance, limited recombination patterns, and common ancestry for subtypes B and D. J Virol. 1997;71:6348–6358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6348-6358.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogenetic Inference Package) version 3.5. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth L M, Buck C, Chaisson R E, Quinn T C, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho D D, Richman D D, Siliciano R F. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997;278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunthard H F, Wong J K, Ignacio C C, Guntelli J C, Riggs N L, Havlir D V, Richman D D. Human immunodeficiency virus replication and genotypic resistance in blood and lymph nodes after a year of potent antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 1998;72:2422–2428. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2422-2428.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch M S, Conway B, D’Aquila R T, Johnson V A, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, Demeter L M, Flammer S M, Jacobsen D M, Kuritzkes D R, Loveday C, Mellors J W, Vella S, Richman D D. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adults with HIV infection. Implications for clinical management. International AIDS Society—USA Panel. JAMA. 1998;279:1984–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.24.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janini L M, Pieniazek D, Peralta J M, Schechter M, Tanuri A, Vicente A C, de la Torre N, Pieniazek N J, Luo C C, Kalish M L, Schochetmon G, Rayfield M A. Identification of single and dual infections with distinct subtypes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Virus Genes. 1996;13:69–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00576981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jong M D, Schuurman R, Lange J M A, Boucher C A B. Replication of a pre-existing resistant HIV-1 subpopulation in vivo after introduction of a strong selective drug pressure. Antivir Ther. 1996;1:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lech W J, Wang G, Yang Y L, Chee Y, Dorman K, McCrae D, Lazzeroni L C, Erickson J W, Sinsheimer J S, Kaplan A H. In vivo sequence diversity of the protease of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: presence of protease inhibitor-resistant variants in untreated subjects. J Virol. 1996;70:2038–2043. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.2038-2043.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health from Brazil. Programa Nacional de DST/AIDS. AIDS Bol Epidemiol. 1996;6:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohri H, Singh M K, Ching W T W, Ho D D. Quantitation of zidovudine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the blood of treated and untreated patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:25–29. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgado M G, Sabino E C, Shpaer E G, Bongertz V, Brigido L, Guimaraes M A, Castilho E A, Galvao-Castro B, Mullins J I, Hendry R M. V3 region polymorphisms in HIV-1 from Brazil: prevalence of subtype B strains divergent from North American/European prototype and detection of subtype F. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:569–576. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers G, Kober B, Hahn B H. Human retroviruses and AIDS. Los Alamos, N. Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nájera I, Holguín A, Quiñones-Mateu M E, Muñoz-Fernandez M A, Nájera R, López-Galindez C, Domingo E. pol gene quasispecies of human immunodeficiency virus: mutations associated with drug resistance in virus from patients undergoing no drug therapy. J Virol. 1995;69:23–31. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.23-31.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nájera I, Richman D D, Olivares I, Rojas J M, Peinado M A, Perucho M, Najera R, Lopez-Galindez C. Natural occurrence of drug resistance mutations in the reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:1479–1488. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potts K E, Kalish M L, Lott T, Orloff G, Luo C C, Bernard M A, Alves C B, Badaro R, Suleiman J, Ferreira O. Genetic heterogeneity of the V3 region of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein in Brazil. AIDS. 1993;7:1191–1197. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabino E C, Diaz R S, Brigido L F, Learn G H, Mullins J I, Reingold A L, Duarte A J, Mayer A, Busch M P. Distribution of HIV-1 subtypes seen in an AIDS clinic in São Paulo City, Brazil. AIDS. 1996;10:1579–1584. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199611000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabino E C, Shpaer E G, Morgado M G, Korber B T M, Diaz R S, Bongertz V, Cavalcante S, Galuão-Castro B, Mullins J I, Mayer A. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope genes recombinant between subtypes B and F in two epidemiologically linked individuals from Brazil. J Virol. 1994;68:6340–6346. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6340-6346.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuyver L, Wyseur A, Rombout A, Louwagie J, Scarcez T, Verhofstede C, Rimland D, Schinazi R F, Rossau R. Line probe assay for rapid detection of drug-selected mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:284–291. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanuri A, Swanson P, Devare S, Berro O J, Savedra A, Costa L J, Telles J G, Brindeiro R, Schable C, Pieniazek D, Rayfield M. HIV-1 subtypes among blood donors from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr, 1999;20:60–66. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199901010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. HIV type 1 variation in World Health Organization-sponsored vaccine evaluation sites: genetic screening, sequence analysis, and preliminary biological characterization of selected viral strains. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:1327–1343. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong J K, Hezareh M, Günthard H F, Havlir D V, Ignacio C C, Spina C A, Richman D D. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged supression of plasma viremia. Science. 1997;278:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]