Abstract

Household air pollution from solid fuel combustion was estimated to cause 2.31 million deaths worldwide in 2019; cardiovascular disease is a substantial contributor to the global burden. We evaluated the cross-sectional association between household air pollution (24-hour gravimetric kitchen and personal particulate matter (PM2.5) and black carbon (BC)) and C-reactive protein (CRP) measured in dried blood spots among 107 women in rural Honduras using wood-burning traditional or Justa (an engineered combustion chamber) stoves. A suite of 6 additional markers of systemic injury and inflammation were considered in secondary analyses. We adjusted for potential confounders and assessed effect modification of several cardiovascular-disease risk factors.

The median (25th, 75th percentiles) 24-hour-average personal PM2.5 concentration was 115 μg/m3 (65,154 μg/m3) for traditional stove users and 52 μg/m3 (39, 81 μg/m3) for Justa stove users; kitchen PM2.5 and BC had similar patterns. Higher concentrations of PM2.5 and BC were associated with higher levels of CRP (e.g., a 25% increase in personal PM2.5 was associated with a 10.5% increase in CRP [95% CI: 1.2–20.6]). In secondary analyses results were generally consistent with a null association. Evidence for effect modification between pollutant measures and four different cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., high blood pressure) was inconsistent. These results support the growing evidence linking household air pollution and cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: household air pollution, cookstoves, C-reactive protein, biomass, black carbon, particulate matter

1. Introduction

Short-term and long-term exposure to particulate matter is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Atkinson, Kang, Anderson, Mills, & Walton, 2014; Brook et al., 2010; Franklin, Brook, & Arden Pope, 2015; Gold & Mittleman, 2013; Hoek et al., 2013; Newby et al., 2015; Polichetti, Cocco, Spinali, Trimarco, & Nunziata, 2009; C. A. Pope, 2000). The use of solid biomass fuels, such as wood, dung or crop residue, for cooking and heating results in high levels of chronic exposure to particulate matter and black carbon (BC). The majority of the household air pollution burden of disease is among those living in low and middle income countries (LMIC), where approximately 80% of worldwide cardiovascular deaths occur (Bowry, Lewey, Dugani, & Choudhry, 2015). Exposure to household air pollution was estimated to be responsible for 91.5 million disability-adjusted life years and 2.31 million deaths in 2019 (Bennitt, Wozniak, Causey, Burkart, & Brauer, 2021; Health Effects Institute, 2020). There is evidence that exposure to household air pollution is associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Lee et al., 2020; Shupler et al., 2020).

Numerous plausible mechanistic pathways may explain the association between particulate matter and cardiovascular disease including systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress (Brook et al., 2010; Caravedo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2003; C. Arden Pope et al., 2016). The expression of circulating C-reactive protein (CRP) is an indication of systemic general inflammatory activity and a predictor of future cardiovascular disease as well as all-cause mortality (Johnson et al., 2004; Ridker, 2003). Supporting evidence exists for exposure to ambient air pollution and increased levels of CRP (W. Li et al., 2017; Y. Li, Rittenhouse-Olson, Scheider, & Mu, 2012). Additional biomarkers of inflammation such as (Serum Amyloid A [SAA], Interleukin 1-β [IL1β], IL-8, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α [TNF-α], Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 [ICAM-1], and Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule [VCAM-1]), are also indicators of increased endothelial inflammation and cardiovascular disease(Teixeira et al., 2014). There is suggestive evidence from the field of household air pollution that demonstrates associations between cleaner-burning stoves and measured household air pollution and these biomarkers (Caravedo et al., 2016; Dutta, Ray, & Banerjee, 2012; Olopade et al., 2017).

Quantifying associations between household air pollution and cardiovascular disease in rural, low-resource settings is challenging, especially when clinical disease outcomes are measured (Mcdade, Williams, & Snodgrass, 2007). Biomarkers of subclinical cardiovascular disease are feasible to measure in the field and have been utilized in household air pollution studies (Caravedo et al., 2016; Dutta et al., 2012; Dutta, Roychoudhury, Chowdhury, & Ray, 2013; Olopade et al., 2017; Young et al., 2019). Although standard practice is to measure biomarkers in serum drawn from venous blood, logistical challenges in the field often prevent direct blood draws due to a lack of equipment and facilities for sample processing and preservation (Mcdade et al., 2007). The use of dried blood spots to quantify inflammatory markers has grown in utility over the past decade in both clinical and research applications due to the increased convenience, low-cost, and reliability of the methods (Miller & McDade, 2012). The use of dried blood spots to measure CRP is particularly promising. Through our feasibility study in Nicaragua among 54 women, we demonstrated low within-person variability in CRP concentrations as measured daily in dried blood over a 4-day period and positive associations between exposure to household air pollution and increased levels of CRP among wood-burning cookstove users (Young et al., 2019). Specifically, we reported that a 25% increase in kitchen PM2.5 was associated with a 7.4% increase in CRP measured in dried blood spots (Young et al., 2019).

In this cross-sectional study among 107 rural Honduran women, we used a minimally invasive method of finger-stick dried blood spots to assess the association between systemic inflammation and the previous 24-hour average exposure to household air pollution. In this study, we built upon our previous work in Nicaragua and added several important indicators of exposure including measured concentrations of personal PM2.5 and kitchen and personal BC. Our primary analysis focused on CRP, a decision based largely on the role of CRP as an important indicator of future disease risk and the results of our feasibility study (Young et al., 2019). Although CRP itself is not likely causally involved in cardiovascular events, it is consistently reflective of underlying proinflammatory pathways that mediate disease (Eiriksdottir et al., 2011). For our secondary analyses, we measured additional markers of systemic injury and inflammation (SAA, IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1). Further, we hypothesized that the association between household air pollution and CRP may be stronger among a subset of the population with risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as increased age, higher body mass index (BMI), higher levels of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and higher blood pressure (Dubowsky, Suh, Schwartz, Coull, & Gold, 2006).

2. Materials and Methods

Study protocols were approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Study Population

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 11 rural communities surrounding La Esperanza which is home to approximately 15,000 people and located in the mountainous region of Western Honduras. Participants were a convenience sample recruited into the study from a sample of more than 500 households screened in a household survey. We obtained exposure and health measurements from 150 female primary cooks near La Esperanza between February and April 2015 (dry season). Enrollment criteria required that the primary cook own a traditional stove or a cleaner-burning Justa cookstove (built at least 4 months prior to the interview) and be 25–56 years old, a non-smoker, and not pregnant. Traditional cookstoves in the communities are typically self-built wood-burning stoves, with a metal griddle and a chimney. Justa cookstoves are a common wood-burning stove model in Central America. The Justa design includes a rocket-elbow combustion chamber, metal griddle, and chimney. Study participants provided informed consent and, following data collection, received an incentive of USD$5 worth of food items for their participation.

2.2. Exposure to Household Air Pollution

We measured kitchen and personal 24-hour concentrations of PM2.5 and BC. Fine particle concentrations were measured gravimetrically using Triplex cyclones with a particle cut size of 2.5μm (BGI by Mesa Labs, Butler NJ, USA). Air was pulled through the cyclone by an external pump (SKC AirCheck XR5000, SKC Inc, Eighty Four, PA, USA) that was pre-calibrated daily using a flow meter (DryCal Dc-Lite, Bios International, Mesa Labs, NJ, USA) and set to a flow rate of 1.5 L/min. PM2.5 was collected on 37-mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-coated glass fiber filters (Fiberfilm™ T60A20, Pall Corporation, Port Washington KY, USA). Prior to sampling, the filters were equilibrated for at least 24-hours and then pre-weighed at Colorado State University (CSU) using a microbalance (Mettler Toledo Microbalance, model MX5, resolution and repeatability of 1-ug, Columbus, OH, USA).

Kitchen exposure monitors were placed between 76 and 127 centimeters above the stove and away from open windows and doors. For personal exposure, the sampling pump was placed in a small bag that each participant wore over their shoulder for the 24-hour period (except when bathing or sleeping). Women were instructed to place the bag with the monitor next to their bathing area or bed when not wearing it. The inlet to the cyclone was clipped to a strap on the woman’s chest near her breathing zone. After collection of the sample, filters were stored at −22°C and then transported to CSU, equilibrated for at least 24-hours, and post-weighed for particulate matter mass. One filter blank was collected every two weeks (n=7).

We calculated the 24-hour average gravimetric PM2.5 concentration as the change in sample filter mass (adjusted for the average mass change in blank filters) divided by the total volume of air sampled. The PM2.5 mass limit of detection (LOD) was calculated as follows: average mass of blank filters plus 3 times the standard deviation (SD) of the sample blank filter masses. All samples with a mass less than the LOD of 54 μg (7 kitchen samples and 7 personal samples) were replaced with a value of LOD/√2 (MacDougall et al., 1980). Due to a broken DryCal volumetric flow meter needed to calibrate the PM2.5 sampling pump, we were unable to collect PM exposure measures from the first 41 houses recruited into the study. Additional samples were excluded from analysis due to: AirCheck pumps running for less than 75% of the intended time (<18 hours) (three personal and two kitchen samples), negative filter weight (one personal PM2.5 sample), and missing flow post-calibration data in the field (one kitchen PM2.5 sample).

BC concentrations were estimated based on the optical transmission of light through the filters (Hansen et al, 1984) using a transmissometer (model OT-21, Magee Scientific, USA). Transmission data were converted to mass concentrations based on published mass-absorption values for combustion aerosols (Chylek, Ramaswamy, Cheng, & Pinnick, 1981) and corrected for a filter loading artifact wherein an underestimation occurs at high sample loading (Kirchstetter & Novakov, 2007). We calculated a BC concentration using the sample air flow and duration. The LOD was estimated to be equivalent to a minimum concentration 0.86 μg/m3 which corresponds to three times the standard deviation of BC concentrations from 54 blank samples (additional blank filters were used from field sampling campaigns in Honduras conducted within the same year to estimate the reference values for the transmissometer). Values below the LOD (3 kitchen samples and 10 personal samples) were substituted by LOD/√2. For more detailed information on BC methodologies, please see Chylek et al, 1981, Kitchstetter and Novakov, 2007, and supporting information in our previous publication (Young et al., 2018).

2.3. Markers of Systemic Injury and Inflammation

Markers of systemic injury and inflammation were assessed via dried blood (Mei, Alexander, Adam, & Hannon, 2001). To obtain the dried blood spots, each woman had her middle or ring finger cleaned with a 70% alcohol swab. Once the finger was dry, it was pricked with a sterile disposable 1.75 mm point BD Genie™ lancet (BD, Franklin Lakes, USA). The first drop of blood was wiped away using sterile gauze to prevent contamination from possible tissue fluid or skin. Blood was then spotted onto a standardized filter paper (See Figure 1) (903 Protein Saver Card, Schleicher & Schuell, NH). Participants provided up to 5 spots on the card. The samples were obtained in the morning between 7:30am and 12:00pm, immediately following the 24-hour exposure assessment. After collection, samples were allowed to dry for 24-hours at room temperature, placed in baggies with desiccant and humidity indicator cards, and stored frozen at −22°C in Honduras. The samples were transported (off ice for less than 24 hours) and stored at CSU at −80°C. Samples were shipped overnight (on dry ice) from CSU to the National Health and Environmental Effects Laboratory of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for analysis. Analyses were performed on the Meso Scale Multiplex instrument (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). The V-PLEX Plus Vascular Injury Panel 2 (human) kit was used to measure ICAM-1, VCAM-1, CRP, SAA. The Human Pro-Inflammatory-4 II Base Kit was used for proinflammatory mediators (IL-Iβ, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8). One 6 mm circle was punched from one blood spot on each card. The punches were transferred to 96-well plates (one punch per well) and a 200 μL extraction buffer (PBS with 0.5% tween-20) was added to each well. Each plate was sealed and placed on a shaker table overnight in a 4°C refrigerator. Plates were stored in a −80°C freezer prior to analysis. For analysis, the extraction liquids were measured in a 1:200 dilution factor for the V-PLEX plus vascular injury kit and without any dilution for the pro-inflammatory mediator kit. The QuickPlex 120 instrument directly outputs data. The reliability (intra-plate variability) and reproducibility (inter-plate variability) were tested for all assays and were below a 10% coefficient of variation. We evaluated the lower LOD for each inflammatory marker according to the company specifications (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). Samples with a value below the LOD for the inflammatory marker were substituted with the LOD/√2 (MacDougall et al., 1980). Five of the inflammatory markers had no values less than the LOD (CRP, SAA, IL-8, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1). For IL-1β, we substituted one value less than the LOD (LOD=0.04 ng/mL), while we substituted 37 values for TNF-α (LOD =0.04 ng/mL). For IL-6, 89% (127 samples) were below the LOD of 0.06 ng/mL, therefore we did not evaluate this marker in further analyses.

Figure 1: Protein saver card and dried blood spot.

Photo Credit: Joanna B Pinneo Photography, https://www.joannabpinneophoto.com/index

2.4. Additional Information

2.4.1. Population Demographics and Covariates

The study team administered in-person demographic surveys in the homes of participants. Responses were recorded on a tablet into an electronic data collection system, Open Data Kit (Brunette et al., 2013). We ascertained data on the number of beds per person in the household, years of formal education, access to electricity, the number of assets owned (cars, bikes, motorbikes, televisions, radios, refrigerators, sewing machines), and diet to calculate a dietary diversity score. For the dietary diversity score, women reported all food eaten in the previous 24-hour period and the number of portions (Arps, 2011). The final dietary diversity score was a sum of the number of food groups a woman had eaten at least one portion of in the past 24 hours. Scores ranged from 1 to 10 and served as an indicator of socioeconomic status (SES). Surveys were also used to collect information on cooking and exposure to secondhand smoke. Women self-reported any medication use at the time of the study. Anthropometric data were gathered at the homes of women. Participant’s waist circumference, weight (kilograms), and height (meters) were measured. BMI was calculated by dividing the weight by the square of the height.

2.4.2. Effect Modification Covariates

To estimate diabetes-related information for our effect modification analyses, we measured HbA1c with a 5 μl finger stick sample of blood. The sample was analyzed in the field with the A1CNow+® system (PTS Diagnostics, Indianapolis, USA). We categorized participants into having normal levels of HbA1c (HbA1c <5.7%) or elevated levels (HbA1c ≥5.7%) (American Diabetes Association, 2018). Blood pressure was measured using the SphygmoCor XCEL Central Blood Pressure Measurement System (AtCor Medical Pty Ltd, Australia), recorded at the brachial artery on the woman’s right arm with a 23–33 cm cuff. Three consecutive measurements were taken for each participant after a 10-minute rest period. The average of the last two measurements was recorded. We categorized blood pressure into normal blood pressure (systolic <120 mmHg and diastolic <80 mmHg) and elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥120 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥80 mmHg) (Whelton et al., 2018). BMI was estimated as described above.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS® software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R, version 3.4.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Descriptive statistics were determined for population characteristics and pollutant concentrations for the entire population and stratified by stove type used within the home. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated between pollutants. Descriptive statistics and Spearman correlation coefficients were also calculated for the 7 inflammatory markers.

In primary analyses we evaluated the associations between PM2.5 (personal and kitchen) and BC (personal and kitchen) with each of the inflammatory markers using a separate multiple linear regression model for each exposure-outcome combination. We logarithmically transformed both PM2.5 and BC exposure concentrations as well as all inflammatory markers to meet the assumptions of linear regression. For all analyses, we removed participants who self-reported use of hypertension medications (n=3), use of vitamins and/or folic acid (n=22), or anti-inflammatory medications (n=11). Potential confounding variables were chosen a priori based on previous literature and included age, education, a marker of anthropometry, and a marker of socioeconomic status. We evaluated options for markers of anthropometry (BMI, height, weight, and waist circumference) and measures of socio-economic status (including dietary diversity score, number of assets owned, electricity, beds per person, and education level) based on crude associations with the biomarkers. In our final models, we controlled for age, body-mass index, assets owned (< 2 assets or ≥2 assets), electricity (yes/no) and years of school (< 6 or ≥6 years). We also conducted sensitivity analyses and re-ran final models: 1.) including a term for community in order to account for non-independence of participants within communities, and 2). the removal of five participants who reported occasional secondhand smoke exposure.

We explored effect modification by risk factors for cardiovascular disease including age (<40 or ≥40 years), BMI (<25.1 or ≥25.1 kg/m2, the median value in our dataset), HbA1c levels (normal [<5.7] vs. elevated [≥5.7%]) and a one-time measure of blood pressure (normal [systolic <120 mmHg and diastolic <80 mmHg] vs. elevated [systolic ≥120 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥80 mmHg]) by adding an interaction term for each of the candidate modifying factors and each of the exposure variables in the models. We considered effect modification results to be significant based on a p-value of 0.05 or less for the interaction term.

3. Results

We enrolled 150 women in our cross-sectional study; a total of 146 women were included in our sample. Two participants declined to provide dried blood samples, and two women had incomplete samples. Population characteristics are presented in Table 1. The average age of women in the study was 37.3 years (SD: 8.9), average BMI was 25.9 kg/m2 (SD: 4.1), and about half the population (n=67) had less than 6 years of education. Most variables were similar between the two stove groups; there was a suggestive difference in education status (51.4% of traditional stove users had less than 6 years of education compared to 41.7% of Justa stove users).

Table 1:

Population characteristics among nonsmoking primary female cooks using traditional or cleaner-burning Justa stoves, rural Honduras (N=146)

| Total (N=146) | Traditional (N=73) | Justa (N=73) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or Mean (SD) | N (%) or Mean (SD) | N (%) or Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 37.3 (8.9) | 38.4 (9.4) | 36.1 (7.9) |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 25.9 (4.1) | 25.8 (4.5) | 26.0 (3.8) |

| Categorized BMI | |||

| <25.1 | 67 (46%) | 36 (49.3%) | 31 (42%) |

| ≥ 25.1 | 79 (54%) | 37 (50.7%) | 42 (58%) |

| Elevation (meters) † | 1913 (103) | 1990 (91) | 1936 (109) |

| Years of education ‡ | |||

| Less than six years | 67 (46.5%) | 37 (51.4%) | 30 (41.7%) |

| Six or more years | 77 (53.5%) | 35 (48.6%) | 42 (58.3%) |

| Electricity † | |||

| No | 119 (82.1%) | 61 (83.6%) | 58 (80.6%) |

| Yes | 26 (17.9%) | 12 (16.4%) | 14 (19.4%) |

| Number of assets | |||

| Less than 2 | 69 (47.3%) | 33 (45.2%) | 36 (49.3%) |

| Two or more | 77 (52.7%) | 40 (54.8%) | 37 (50.7%) |

| Years spent cooking with biomass | 25.8 (9.7) | 26.8 (10.5) | 24.8 (8.8) |

| Self-reported exposure to secondhand smoke | 5 (3.4%) | 5 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Systolic blood pressure | 118.6 (12.7) | 120.4 (12.2) | 116.8 (13.1) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 73.1 (8.6) | 73.8 (9.4) | 72.4 (8.9) |

| Blood Pressure | |||

| Normal (systolic <120 mmHg and diastolic <80 mmHg) | 118 (80.8%) | 54 (74%) | 64 (88)% |

| Elevated (systolic ≥120 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥80 mmHg) | 28 (19%) | 19 (26%) | 9 (12%) |

| HbA1c § | 5.5 (0.75) | 5.5 (0.4) | 5.6 (1.0) |

| Glycated Hemoglobin | |||

| Normal (HbA1c <5.7%) | 104 (74%) | 54 (76%) | 50 (73%) |

| Elevated (HbA1c ≥5.7%) | 36 (25%) | 17 (24%) | 19 (27%) |

N=145; Traditional=73, Justa=73

N=144; Traditional=73, Justa=72

N=140; Traditional=71, Justa=69

3.1. Exposure concentrations

For the exposures, the final sample sizes for the pollutant measurements was 105 for personal PM2.5, 106 for personal BC and kitchen PM2.5, and 107 for kitchen BC (the final sample sizes for PM2.5 and BC differed by one measurement each due to the a negative filter weight (one personal PM2.5 sample) and missing flow post-calibration data in the field (one kitchen PM2.5 sample); these measurements were retained in the BC analyses). Twenty-four hour minimum, maximum, median, 25th and 75th percentile concentrations of each pollutant are shown in Table 2. As expected, kitchen PM2.5 (n=106) was higher than personal PM2.5 (n=105) with median concentration of 132 μg/m3 (25th and 75th percentile: 62 μg/m3, 374 μg/m3) compared to 80 μg/m3 (25th and 75th percentile: 51 μg/m3, 137 μg/m3). The same pattern holds for kitchen and personal BC. In addition, women who owned traditional stoves were exposed to higher concentrations of each of the two pollutants than women who owned Justa stoves (Table 2). For example, the median 24-hour-average personal PM2.5 concentration was 115 μg/m3 (25th and 75th percentile: 65 μg/m3, 154 μg/m3) for traditional stove users (n=62) and 52 μg/m3 (25th and 75th percentile: 39 μg/m3, 81 μg/m3) for Justa stove users (n=43). The 24-hour averages of the four pollutant measures (kitchen and personal PM2.5 and kitchen and personal BC) were strongly correlated. Within pollutants, there was a positive correlation between kitchen concentrations and personal concentrations to PM2.5 (Spearman rho=0.80) and kitchen and personal BC (Spearman rho=0.77). PM2.5 and BC exposures were correlated among kitchen measurements (Spearman rho=0.89) and personal measurements (Spearman rho=0.78).

Table 2:

24-hour average kitchen and personal fine particulate matter and black carbon concentrations, traditional and Justa stove users, rural Honduras

| All Participants | Traditional Stove Users | Justa Stove Users | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Min | 25th | Median | 75th | Max | n | Min | 25th | Median | 75th | Max | n | Min | 25th | Median | 75th | Max | |

| 24-hour average kitchen PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 106 | 18 | 62 | 132 | 374 | 1654 | 62 | 18 | 91 | 181 | 511 | 1654 | 44 | 18 | 38 | 71 | 159 | 1134 |

| 24-hour average personal PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 105 | 18 | 51 | 80 | 137 | 346 | 62 | 18 | 65 | 115 | 154 | 346 | 43 | 18 | 39 | 52 | 81 | 174 |

| 24-hour average kitchen Black Carbon (μg/m3) | 107 | 1 | 9 | 21 | 82 | 1172 | 63 | 1 | 15 | 44 | 114 | 1172 | 44 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 19 | 469 |

| 24-hour average personal Black Carbon (μg/m3) | 106 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 18 | 123 | 62 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 32 | 123 | 44 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 47 |

PM2.5: fine particulate matter

3.1.2. Markers of Systemic injury and Inflammation

Overall summary statistics for the seven inflammatory markers measured in dried blood spots are presented in Table 3. We had 110 participants with valid blood spot data. Participants had a median CRP level of 13.6 per ng/mL (25th-75th: 5.8–27.5 per ng/ml). Several markers were moderately correlated, CRP and SAA (Spearman rho = 0.49) and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (Spearman rho=0.71), while other markers exhibited low or no correlation (Table 3).

Table 3:

Median (25th and 75th percentiles) and Spearman rank correlation between markers of systemic injury and inflammatory (N=110)

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | TNFa | CRP | SAA | ICAM-1 | VCAM-1 | IL-1B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-8 | 5.8 (4.9, 8.2) | 0.26 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.22 |

| TNF-a | 0.06 (0.04, 0.07) | 1 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.14 |

| CRP † | 13.6 (5.8, 27.5) | - | 1 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| SAA † | 28.9 (17.9, 52.8) | - | - | 1 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| ICAM-1 † | 6.9 (5.9, 8.5) | - | - | - | 1 | 0.71 | 0.1 |

| VCAM-1 † | 11.2 (9.8, 13.3) | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.18 |

| IL-1 β | 0.20 (0.1, 0.20) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

Concentrations presented per ng/mL

Interleukin 8 (IL-8), Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), Serum Amyloid A (SAA), Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule (VCAM-1) Interleukin 1-β (IL-1β)

3.1.3. Primary analysis of CRP

In our linear models, our sample size was limited to participants who had valid exposure measurements, valid dried blood spot samples, and who did not take medications (Kitchen PM2.5: n=74; personal PM2.5: n=73; Kitchen BC: n=75; personal BC: n=75; stove-type: n=73). The analytical sample did not differ by demographic characteristics from the full study sample (data not presented). Higher levels of PM2.5 were associated with higher levels of CRP (Table 4). For example, a 25% increase in personal PM2.5 concentrations resulted in a 10.5% (95% CI: 1.2 – 20.6) increase in CRP concentrations after controlling for potential confounders (age, body mass index (BMI), number of assets (<2 or ≥2), electricity (yes/no), years of education (<6 or ≥6). Because of the natural-log transformation of our modeled PM2.5 exposure variable, the 25% increase in personal PM2.5 associated with the 10.5% increase in CRP represents a different absolute difference in PM2.5 at varying points along the observed PM2.5 continuum; for example, at the 25th percentile the corresponding absolute difference is 13 μg/m3 (i.e., from 51 μg/m3 to 64 μg/m3) and at the 75th percentile the corresponding absolute difference is 34 μg/m3 (i.e., from 137 μg/m3 to 171 μg/m3). Similar positive results were observed between higher kitchen concentrations of BC and higher CRP concentrations, while there was a suggestive positive association between kitchen PM2.5 and CRP as well as personal BC and CRP.

Table 4:

Estimated adjusted† percentage difference in C-reactive protein per 25% increase in 24-hour average measured pollutant concentration, or by stove type among traditional and Justa stove users, rural Honduras

| Pollutant | N | Percentage Difference in CRP | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kitchen PM2.5 (μg/m3)‡ | 74 | 4.2 | −1.1, 9.7 | |

| Personal PM2.5 (μg/m3)‡ | 73 | 10.5 | 1.2, 20.6* | |

| Kitchen BC (μg/m3)‡ | 75 | 3.9 | 0.1, 7.8* | |

| Personal BC (μg/m3)‡ | 73 | 4.2 | −0.5, 9.1 | |

| Stove type§ | Traditional | 54 | 24.6 | −33.4, 133.1 |

| Justa (ref) | 56 |

Cl: Confidence interval; PM2.5: fine particulate matter; CRP (C-reactive protein)

Sample size included only participants with both exposure and CRP. Models were adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), number of assets (<2 or ≥2), electricity (yes/no), years of education (<6 or ≥6)

In continuous exposure models, CRP and measured pollution were both log transformed. Beta coefficients were entered into the formula ((1.25^β)-1) and multiplied by 100. We can interpret the estimate of the continuous pollution exposures as a percent increase in inflammatory marker for each 25% increase in exposure. Example: There is a 10.5% higher CRP level with a 25% higher personal PM2.5 concentration.

Inflammatory marker was log-transformed. Categorical variable beta coefficients were entered into the formula (e^β−1)*100). The estimates for the categorical measures of exposure can be interpreted as the percent difference in inflammatory marker when comparing traditional stove to the reference (Justa stove).

Significant at the 0.05 level

We observed that women who used traditional stoves had CRP levels that were 24.6% higher than women who used Justas stoves (95% CI: −33.4 – 133.1) (Table 4).

3.1.4. Secondary Analysis of Markers of Systemic injury and Inflammation

Among our secondary biomarkers, we also observed associations between all four continuous pollutants and SAA (Supplement Table 1). A 25% increase in personal PM2.5 exposure was associated with an 8.3% increase in SAA concentrations (95% CI: 2.3, 14.7). Additionally, a 25% higher kitchen black-carbon concentration was associated with 1.9% higher IL-8 concentration (95% CI: 0.4–3.5) in finger prick blood samples. We did not observe any associations between household air pollution concentrations and IL-1β, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, or TNF-α.

In general, the cookstove type (traditional or Justa) was not associated with secondary markers of inflammation with the exception of SAA. We observed that women who owned a traditional stove had a 59.8% higher SAA level compared to women who used a Justa cookstove (95% CI: 10.2 – 131.8). Separate sensitivity analyses including a term for community and removing participants exposed to second-hand smoke did not influence results (results not shown).

3.2. Effect Modification

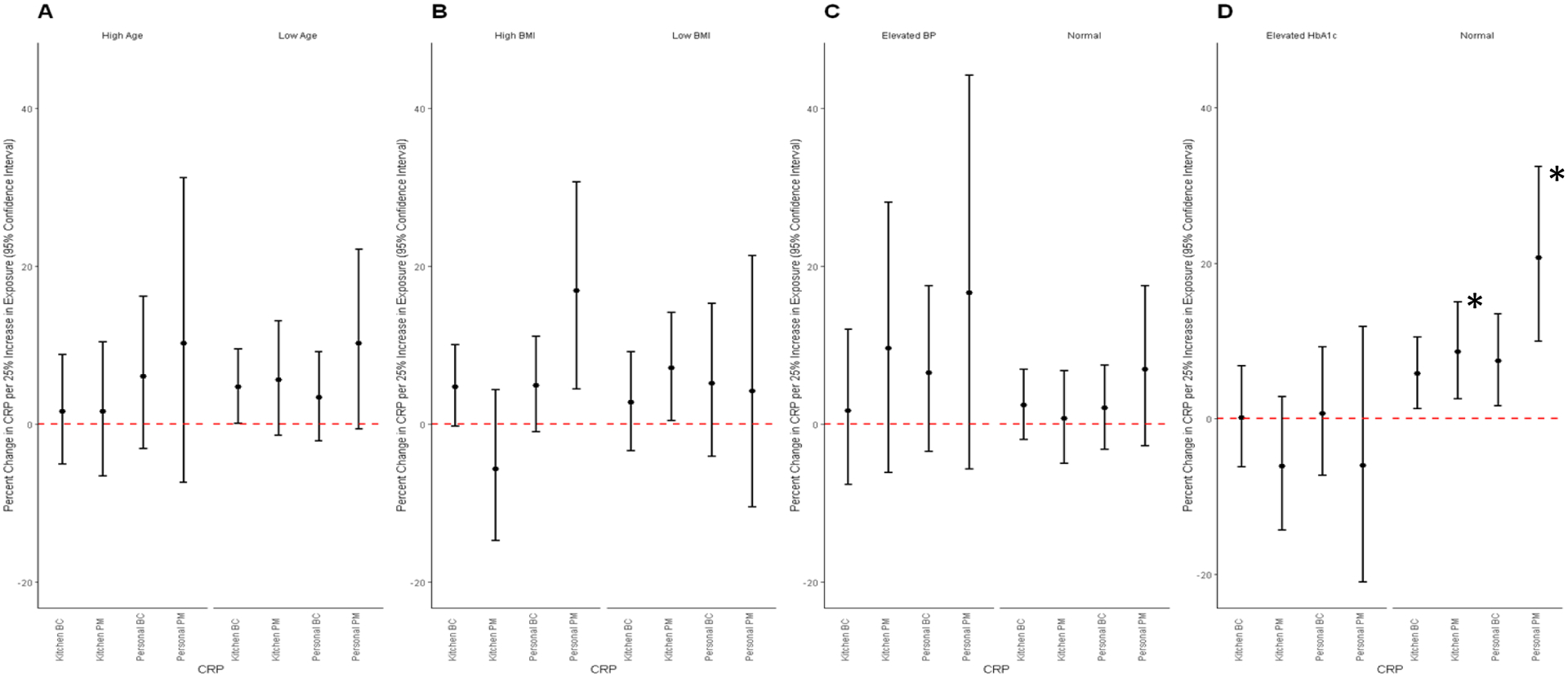

For effect modification analyses, 18 of 110 women reported no cardiovascular risk factors. Of those who reported only one risk factor, 13 had only age > 40 years as a risk factor, 15 had only high BMI (≥25.1 kg/m2), five women had only high blood pressure, and 11 were classified as only having high HbA1c (Figure 2), the others had multiple risk factors. Although we hypothesized effects of household air pollution on CRP to be stronger among those in our population with cardiovascular disease risk factors; patterns were not consistent with this hypothesis (Figure 3). For example, we observed a stronger positive association between household air pollution and CRP among women who were classified as “normal” compared to the elevated HbA1c group. A 25% higher kitchen PM2.5 concentration was associated with an 8.6% (95% CI: 2.6, 15.0) higher CRP concentration among women with elevated HbA1c, while a 25% higher personal PM2.5 concentration was associated with a 20.7% higher CRP among women with normal HbA1c (95% CI: 10.0, 32.4); (p-interaction=0.01) (Figure 3). We did not observe evidence of effect modification on the association of personal PM2.5 and CRP for other factors including categories of BMI (pinteraction=0.22) or blood pressure (p-interaction=0.46). Similarly inconsistent effect modification results were observed for the secondary markers of systemic injury and inflammation (Supplement Figures 1–4). Further, we did not observe consistent patterns of pollutant concentration distributions by risk factor groupings that may have helped with interpreting effect modification results (Supplemental Table 2). For example, if those with normal HbA1c were, on average, in a lower distribution range of PM2.5 as compared to those with elevated HbA1c, these results could have suggested that the stronger effect of PM2.5 on CRP among those with normal HbA1c was due to the exposure-response being stronger at lower PM concentrations.

Figure 2: Venn diagram of risk factors for cardiovascular disease (N = 110).

†18 participants did not have any risk factor

BMI = body mass index, HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin

Figure 3. Associations between 24-hour average pollutant concentrations and levels of C-reactive protein (CRP).

Models were adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), number of assets (<2 or ≥2), electricity (yes/no), years of education (<6 or ≥6)

A: Model for age; Low age = <40 years old (N =47 kitchen PM, N= 48 for personal PM, kitchen BC and personal BC); high age = ≥40 years old (N = 27 for kitchen PM and kitchen BC, N=25 for personal PM and personal BC)

B: Model for BMI; Low BMI = BMI <25.1 kg/m3 (N = 31 for kitchen PM and kitchen BC, N=30 for personal PM and personal BC); high BMI = ≥ 25.1 kg/m ( N =44 kitchen BC, N= 43 for personal PM, kitchen BC and personal BC)

C: Model for blood pressure; Normal blood pressure= normal blood pressure (systolic <120 mmHg and diastolic <80 mmHg) (N = 53 for kitchen PM, personal PM, and personal BC, N= 54 for kitchen BC); Elevated BP = elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥120 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥80 mmHg) (N=19 for kitchen PM and kitchen BC, N=18 for personal PM and personal BC)

D: Model for HbA1c: Normal HbA1c = HbA1c <5.7% (N = 61 for kitchen PM and kitchen BC, N=60 for personal PM and personal BC); Elevated HbA1c = HbA1c ≥5.7

*Statistically significant at the 0.05 level

4. Discussion

4.1. CRP

We observed evidence of associations between higher household air pollution, i.e., PM2.5 and BC, and higher levels of CRP among female primary cooks. CRP is an important clinical biomarker and indicator of systemic inflammation with seemingly little diurnal or seasonable variability (Langrish et al., 2012; Pearson et al., 2003). CRP has demonstrated low within-person variability in previous studies; a measure of CRP on four consecutive days in Nicaragua had an interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.88 (Young et al., 2019). Although limited by a cross-sectional design, these results suggest that inhalation of smoke from cooking with biomass may result in systemic inflammation with potential implications for future cardiovascular disease risk.

Household air pollution studies with less sensitive measures of exposure (i.e. indicators for stove type) show mixed results for associations with CRP. A study in India demonstrated that women using biomass stoves had 3.3 times as much serum CRP than age-matched liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) users (Dutta et al., 2012). On the contrary, two studies in Peru among exposed and non-exposed biomass users have shown negative and null associations between biomass users and CRP levels (Caravedo et al., 2016; Kephart et al., 2020). A cross-sectional analysis of measured 48-hour concentrations of kitchen and personal PM2.5 and BC in Peru also showed null associations with CRP in dried blood spots (Fandiño-Del-Rio et al., 2021).

Our results are largely consistent with literature showing associations between measured ambient air pollution, especially particulate matter, and CRP (Liu et al., 2019). Although a direct comparison between the current results and past work should be interpreted carefully (due to differences in exposure instrumentation, exposure ranges, and sample size), our results are consistent with our previous feasibility work with measured household air pollution, demonstrating that among 54 women in Nicaragua, a 25% increase in 48-hour household PM2.5 was associated with a 7.4% (95% CI: 0.7 – 14.5%) increase in CRP measured in dried blood spots (Young et al., 2019). Our measured kitchen exposures demonstrated that a 25% increase in 24-hour average kitchen PM2.5 was associated with a 4.2% increase in CRP (95% CI: −1.1 – 9.7%). Our current study adds additional information on personal exposure to PM2.5 and personal and kitchen BC and CRP concentrations.

4.2. Secondary Analysis of Markers of Systemic Injury and Inflammation

Our results on the secondary markers of injury and inflammation were mixed and add to the inconsistent results from the field of household air pollution. We observed associations between all measures of household air pollution and SAA. The concentrations of SAA usually correlate with those of CRP (as observed in our study), however some studies indicate SAA to be a more sensitive marker to inflammatory disease than CRP (Johnson et al., 2004; Willerson & Ridker, 2004). We observed limited evidence of associations between household air pollution and other markers of inflammation; however, other studies demonstrate some associations between exposure to household air pollution and increased levels of systemic inflammation. Studies from India have demonstrated that users of biomass stoves compared to liquid-petroleum gas stoves had higher levels of serum IL-8 and TNF-α (Dutta et al., 2012, 2013). A study in Nigeria demonstrated that pregnant women who switched from firewood stoves to ethanol-burning stoves demonstrated lower TNF-α, and higher measured concentrations of PM2.5 were associated with higher levels of IL-8 and TNF-α, but not IL-6 (Olopade et al., 2017). In Peru, measured 48-hour concentrations of kitchen BC were associated with TNF-α (Fandiño-Del-Rio et al., 2021). There may be several reasons for observed associations with CRP and not with other makers of inflammation. It is possible that the complex biological pathways for inflammatory mediators may vary by time from exposure or source of combustion, and thus may trigger a response from some inflammatory markers and not others (Wu, Jin, & Carlsten, 2018). Additionally, it is possible that CRP may be more stable in dried blood (Young et al., 2019) or that other biomarkers may have larger variability for which our study sample may have been underpowered to detect associations with household air pollution.

4.3. Effect Modification

Our findings suggest inconsistencies in observed associations between air pollution concentrations and markers of systemic injury and inflammation by cardiovascular disease risk factors (Eckel, 1997; Leon, 2015; Ortega, Lavie, & Blair, 2016; Sanidas et al., 2017). These types of risk factors have been shown to modify the associations between air pollution and indicators of cardiovascular health (Brook et al., 2010; Dubowsky et al., 2006); however, a systematic review of the effects of air pollution on CRP did not find consistent results for effect modification by categories such as obesity or diabetic status (Y. Li et al., 2012). Contrary to our results of an effect of household air pollution on CRP only among those with normal HbA1c (but in line with our initial hypothesis), Dubowsky et al. observed that associations between ambient PM2.5 and CRP were elevated among people classified as diabetic, overweight, and hypertensive seniors (≥ 60 years old) in the U.S. (Dubowsky et al., 2006). There is some precedence for our finding, however; in a study of long-term exposure to ambient air pollution among residents in Germany, annual levels of PM2.5 were associated with higher measured CRP among participants who did not have diabetes (Pilz et al., 2018). In a study of household air pollution defined as biomass users vs. non-users, Caravedo et al. explored effect modification by age categories (35–44 years, 45–54, 55–64, and 65 and over) and sex, however they found no interaction between these factors and stove type on markers of inflammation (CRP, SAA, ICAM-1 or VCAM-1) (Caravedo et al., 2016). It is challenging to compare studies of measured air pollutants with those using binary measures of stove use and also for those being conducted in different areas with often unmeasured contextual differences; however, further research with more robust study designs should evaluate factors that may modify these associations (Clark & Peel, 2014).

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

Our study builds on our work in Nicaragua and demonstrates the ability to successfully collect dried blood spots in the field setting, and several validation studies have shown high correlations between serum and dried blood spot samples (Miller & McDade, 2012; Qian, 2015; Schmid et al., 2004; Skogstrand et al., 2008). Although this study is cross-sectional, the use of this methodologic approach in future prospective studies will help elucidate the potential impacts of household air pollution on cardiovascular disease risk without relying on the need to follow participants for long periods of time to clinical disease ascertainment or the need to rely on retrospective exposure assessment in case-control studies. The relatively few studies evaluating the association between measured PM2.5 or black carbon and biomarkers of systemic inflammation (Dutta et al., 2013; Fandiño-Del-Rio et al., 2021; Olopade et al., 2017; Young et al., 2019) demonstrate inconsistent results; our study contributes additional data to help elucidate the association. A strength of our study is the relatively large sample size and the measured concentrations of exposures and biomarker outcomes. We measured both kitchen and personal PM2.5 and BC, rather than relying on proxy-measures for exposure (i.e. stove type or biomass use).

Selection bias in our cross-sectional study is a concern due to the recruitment of a convenience sample. However, we believe it is unlikely that selection or participation would be associated with both the exposure and the outcome. Additionally, our one-time measurement of household air pollution and markers of systemic injury and inflammation may not be representative of long-term conditions. Measurement error for biomarkers on the Multiplex instrument could have occurred, but we do not believe any error would be differential with respect to exposure. A limitation of CRP is that is can be impacted by acute events (e.g., respiratory infections) which could reduce the precision of our results. Residual confounding is a potential limitation; however, the population was fairly homogenous with respect to other measured characteristics. Establishing temporality between exposure and outcome is always a concern for cross-sectional studies; we at least partially addressed this limitation by requiring that the Justa stove was installed at least 4 months prior to study enrollment. The cross-sectional nature also reduces our ability to draw conclusions regarding the duration of stove use and potential time needed to observe changes in the outcome. Finally, our stove type results (traditional vs. cleaner-burning Justa) may not be generalizable to other populations or stove and fuel types.

5. Conclusions

Our results indicated that higher exposure to household air pollution was associated with higher levels of CRP, a commonly accepted indicator of future cardiovascular disease risk, among women in rural Honduras. Additional analyses also demonstrated associations with other markers of systemic inflammation, although these were less consistent. Positive associations between exposure to PM2.5 and BC with SAA demonstrate a need to further investigate the importance of SAA in the mechanistic pathway from air pollution exposure to disease. The inclusion of measured BC adds to the limited and inconsistent research on the role of BC from household air pollution and inflammatory markers. Our work further demonstrates the feasibility of dried blood spots as a tool to evaluate markers of systemic inflammation in study areas with limited resources. Our results support the body of research demonstrating an association between air pollution and indicators of cardiovascular disease risk and adds evidence from the field of household air pollution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our Honduran partners and community members for ongoing support of this project. Specifically, we would like to thank Gloribel Bautista Cuellar and Jonathan Stack for their leadership and contributions during fieldwork and data collection.

Funding Source:

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21ES022810. Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations of interest:

Two of the authors, Sebastian Africano and Anibal Pinel and are members of the implementing non-governmental organizations that deploy the cookstove technology studied in this paper. Results of research like this are often shown as evidence of the effectiveness of this particular cookstove technology in publications, including blogs, articles, and grant proposals, which may lead to future funding of these initiatives by individual and/or institutional supporters of the respective organizations. As such, we disclose this information for your review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: This paper does not necessarily reflect EPA policy.

References.

- American Diabetes Association. (2018). Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes−−2018. Diabetes Care, 41(Suppl. 1), S13–S27. 10.2337/dc18-S002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arps Shahna. (2011). Socioeconomic status and body size among women in Honduran Miskito communities. Annals of Human Biology, 38(4), 508–519. 10.3109/03014460.2011.564206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RW, Kang S, Anderson HR, Mills IC, & Walton HA (2014). Epidemiological time series studies of PM2.5 and daily mortality and hospital admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax, 69(7), 660–665. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennitt FB, Wozniak SS, Causey K, Burkart K, & Brauer M (2021). Estimating disease burden attributable to household air pollution: new methods within the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet Global Health, 9, S18. 10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00126-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowry Ashna D. K., Lewey Jennifer, Dugani Sagar B., & Choudhry Niteesh K. (2015). The Burden of Cardiovascular Disease in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Epidemiology and Management. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 31(9), 1151–1159. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. (2010). Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update to the Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 121(21), 2331–2378. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette Waylon, Sundt Mitchell, Dell Nicola, Chaudhri Rohit, Breit Nathan, & Borriello Gaetano. (2013). Open Data Kit 2.0: Expanding and Refining Information Services for Developing Regions.

- Caravedo MA, Herrera PM, Mongilardi N, de Ferrari A, Davila-Roman VG, Gilman RH, et al. (2016). Chronic exposure to biomass fuel smoke and markers of endothelial inflammation. Indoor Air, 26(5), 768–775. 10.1111/ina.12259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chylek P, Ramaswamy V, Cheng R, & Pinnick RG (1981). Optical properties and mass concentration of carbonaceous smokes. Applied Optics, 20(17), 2980–2985. 10.1364/AO.20.002980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Maggie L., & Peel Jennifer L. (2014). Perspectives in Household Air Pollution Research : Who Will Benefit from Interventions ? Curr Envir Health Rpt, 250–257. 10.1007/s40572-014-0021-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowsky Sarah D., Suh Helen, Schwartz Joel, Coull Brent A., & Gold Diane R. (2006). Diabetes, obesity, and hypertension may enhance associations between air pollution and markers of systemic inflammation. Environmental Health Perspectives 114(7), 992–998. 10.1289/ehp.8469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta Anindita, Ray Manas Ranjan, & Banerjee Anirban. (2012). Systemic inflammatory changes and increased oxidative stress in rural Indian women cooking with biomass fuels. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 261(3), 255–262. 10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta Anindita, Roychoudhury Sanghita, Chowdhury Saswati, & Ray Manas Ranjan. (2013). Changes in sputum cytology, airway inflammation and oxidative stress due to chronic inhalation of biomass smoke during cooking in premenopausal rural Indian women. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 216(3), 301–308. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel Robert H. (1997). Obesity and Heart Disease. Circulation, 96(9), 3248 LP – 3250. Retrieved from http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/96/9/3248.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiriksdottir G, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Gudnason V, Folsom AR, Andrews G, et al. (2011). Association between C reactive protein and coronary heart disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ, 342(7794), 425. 10.1136/bmj.d548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandiño-Del-Rio Magdalena, Kephart Josiah L., Williams Kendra N., Malpartida Gary, Boyd Barr Dana, Steenland Kyle, et al. (2021). Household air pollution and blood markers of inflammation: A cross-sectional analysis. Indoor Air, 31(5), 1509–1521. 10.1111/ina.12814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin Barry A., Brook Robert, & Arden Pope C. (2015). Air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Current Problems in Cardiology, 40(5), 207–238. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold Diane R., & Mittleman Murray A. (2013). New insights into pollution and the cardiovascular system: 2010 to 2012. Circulation, 127(18), 1903–1913. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.064337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Effects Institute. (2020). State of Global Air 2020. Special Report. Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek Gerard, Krishnan Ranjini M., Beelen Rob, Peters Annette, Ostro Bart, Brunekreef Bert, & Kaufman Joel D. (2013). Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio- respiratory mortality: a review. Environmental Health, 12(1), 43. 10.1186/1476-069X-12-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. Delia, Kip Kevin E., Marroquin Oscar C., Ridker Paul M., Kelsey Sheryl F., Shaw Leslee J., et al. (2004). Serum Amyloid A as a Predictor of Coronary Artery Disease and Cardiovascular Outcome in Women: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Circulation, 109(6), 726–732. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115516.54550.B1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kephart Josiah L., Fandiño-Del-Rio Magdalena, Koehler Kirsten, Bernabe-Ortiz Antonio, Miranda J. Jaime, Gilman Robert H., & Checkley William. (2020). Indoor air pollution concentrations and cardiometabolic health across four diverse settings in Peru: A cross-sectional study. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source 19(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s12940-020-00612-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchstetter Thomas W., & Novakov T (2007). Controlled generation of black carbon particles from a diffusion flame and applications in evaluating black carbon measurement methods. Atmospheric Environment, 41(9), 1874–1888. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.10.067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langrish JP, Bosson J, Unosson J, Muala A, Newby DE, Mills NL, et al. (2012). Cardiovascular effects of particulate air pollution exposure: Time course and underlying mechanisms. Journal of Internal Medicine, 272(3), 224–239. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02566.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Kuan Ken, Bing Rong, Kiang Joanne, Bashir Sophia, Spath Nicholas, Stelzle Dominik, et al. (2020). Adverse health effects associated with household air pollution: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and burden estimation study. The Lancet Global Health, 8(11), e1427–e1434. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30343-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon Benjamin M. (2015). Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology, biological mechanisms, treatment recommendations and future research. World Journal of Diabetes, 6(13), 1246. 10.4239/wjd.v6.i13.1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Dorans Kirsten S., Wilker Elissa H., Rice Mary B., Ljungman Petter L., Schwartz Joel D., et al. (2017). Short-Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Biomarkers of Systemic Inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 37(9), 1793–1800. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Rittenhouse-Olson Kate, Scheider William L., & Mu Lina (2012). Effect of particulate matter air pollution on C-reactive protein: a review of epidemiologic studies. Rev Environ Health, 27(4), 133–149. 10.1515/reveh-2012-0012.Effect [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Qisijing, Gu Xuelin, Deng Furong, Mu Lina, Baccarelli Andrea A., Guo Xinbiao, & Wu Shaowei. (2019). Ambient particulate air pollution and circulating C-reactive protein level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 222(5), 756–764. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall D, Crummet WB, Amore FJ, Crosby DG, Estes FL, Freeman DH, et al. (1980). Guidelines For Data Acquisition And Data Quality Evaluation In Environmental Chemistry. Analytical Chemistry, 52(14), 2242–2249. 10.1021/ac50064a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdade Thomas W., Williams Sharon, & Snodgrass J. Josh. (2007). What a Drop Can Do : Dried Blood Spots As a. Demography, 44(4), 899–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Joanne V, Alexander J. Richard, Adam Barbara W., & Hannon W. Harry. (2001). Innovative Non- or Minimally-Invasive Technologies for Monitoring Health and Nutritional Status in Mothers and Young Children Use of Filter Paper for the Collection and Analysis of Human Whole Blood Specimens 1, 1631–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Elizabeth M., & McDade THomas W. (2012). A highly sensitive immunoassay for interleukin-6 in dried blood spots. American Journal of Human Biology 24(6), 863–865. 10.1002/ajhb.22324.A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby David E., Mannucci Pier M., Tell Grethe S., Baccarelli Andrea A., Brook Robert D., Donaldson Ken, et al. (2015). Expert position paper on air pollution and cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal, 36(2), 83–93. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olopade Christopher O., Frank Elizabeth, Bartlett Emily, Alexander Donee, Dutta Anindita, Ibigbami Tope, et al. (2017). Effect of a clean stove intervention on inflammatory biomarkers in pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria: A randomized controlled study. Environment International, 98, 181–190. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Francisco B., Lavie Carl J., & Blair Steven N. (2016). Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research, 118(11), 1752–1770. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson Thomas A., Mensah George A., Alexander R. Wayne, Anderson Jeffrey L., Cannon Richard O., Criqui Michael, et al. (2003). Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: Application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 107(3), 499–511. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000052939.59093.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilz Veronika, Wolf Kathrin, Breitner Susanne, Rückerl Regina, Koenig Wolfgang, Rathmann Wolfgang, et al. (2018). International Journal of Hygiene and C-reactive protein (CRP) and long-term air pollution with a focus on ultra fine particles. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 221(3), 510–518. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polichetti Giuliano, Cocco Stefania, Spinali Alessandra, Trimarco Valentina, & Nunziata Alfredo. (2009). Effects of particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5 and PM1) on the cardiovascular system. Toxicology, 261(1–2), 1–8. 10.1016/j.tox.2009.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA (2000). Epidemiology of fine particulate air pollution and human health: Biologic mechanisms and who’s at risk? Environmental Health Perspectives, 108(Supp. 4), 713–723. 10.1289/ehp.00108s4713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C. Arden, Bhatnagar Aruni, McCracken James P., Abplanalp Wesley, Conklin Daniel J., & O’Toole Timothy. (2016). Exposure to Fine Particulate Air Pollution Is Associated with Endothelial Injury and Systemic Inflammation. Circulation Research, 119(11), 1204–1214. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Yuchen. (2015). Comparing and Validating Dried Blood Spots with Plasma for Cytokine Assessments in Environmental Exposure Settings.

- Ridker Paul M. (2003). Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation, 107(3), 363–369. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000053730.47739.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanidas Elias, Papadopoulos Dimitris P., Grassos Harris, Velliou Maria, Tsioufis Kostas, Barbetseas John, & Papademetriou Vasilios. (2017). Air pollution and arterial hypertension. A new risk factor is in the air. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension, 11(11), 709– 715. 10.1016/j.jash.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid Christoph, Wiesli Peter, Bernays René, Bloch Konrad, Zapf Jürgen, Zwimpfer Cornelia, et al. (2004). Decrease in sE-Selectin after Pituitary Surgery in Patients with Acromegaly. Clinical Chemistry, 50(3), 650–652. 10.1373/clinchem.2003.028779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupler Matthew, Hystad Perry, Birch Aaron, Miller-Lionberg Daniel, Jeronimo Matthew, Arku RaphaelE, et al. (2020). Household and personal air pollution exposure measurements from 120 communities in eight countries: results from the PURE-AIR study. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(10), e451–e462. 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30197-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skogstrand Kristin, Ekelund Charlotte K., Thorsen Poul, Vogel Ida, Jacobsson Bo, NørgaardPedersen Bent, & Hougaard David M. (2008). Effects of blood sample handling procedures on measurable inflammatory markers in plasma, serum and dried blood spot samples. Journal of Immunological Methods, 336(1), 78–84. 10.1016/j.jim.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira Bruno Costa, Lopes André Luiz, Macedo Rodrigo Cauduro Oliveira, Correa Cleiton Silva, Ramis Thiago Rozales, Ribeiro Jerri Luiz, et al. (2014). Inflammatory markers, endothelial function and cardiovascular risk. Jornal Vascular Brasileiro, 13(2), 108–115. 10.1590/jvb.2014.054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton Paul K., Carey Robert M., Aronow Wilbert S., Casey Donald E., Collins Karen J., Dennison Himmelfarb Cheryl, et al. (2018). 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Pr. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 71(19), e127–e248. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willerson JT, & Ridker Paul M. (2004). Inflammation as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor. Circulation, 109, II-2–II–10. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129535.04194.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Weidong, Jin Yuefei, & Carlsten Chris. (2018). Inflammatory health effects of indoor and outdoor particulate matter. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 141(3), 833–844. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Bonnie N., Clark Maggie L., Rajkumar Sarah, Benka-Coker Megan L., Bachand Annette, Brook Robert D., et al. (2018). Exposure to household air pollution from biomass cookstoves and blood pressure among women in rural honduras: a cross-sectional study. Indoor Air, (July), 1–13. 10.1111/ina.12507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Bonnie N., Peel Jennifer L., Nelson Tracy L., Bachand Annette M., Heiderscheidt Judy M., Luna Bevin, et al. (2019). C-reactive protein from dried blood spots: Application to household air pollution field studies. Indoor Air, (July), 1–7. 10.1111/ina.12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.