Abstract

Objectives:

Children of color and from low-income families experience disparities in hospital care and outcomes. This study examined the experiences of parents and providers who participated in a novel patient navigation program designed to address these disparities.

Methods:

Between April and October 2018, we conducted semi-structured interviews with parents enrolled in the Family Bridge navigation pilot study, and inpatient care providers. Each set of interviews was thematically coded and analyzed according to the Realist Evaluation Framework of context, mechanism and outcomes; to identify how and when the program worked, for whom, and with what results.

Results:

Of 60 parents enrolled in the intervention, 50 (83%) completed an interview. Enrolled children all had public insurance; 66% were Hispanic, 24% were non-Hispanic Black, and 36% of parents preferred Spanish for communication. Of 23 providers who completed an interview, 16 (70%) were attending physicians. Parents identified four contexts influencing intervention effectiveness: past clinical experience, barriers to communication, access to resources, and timing of intervention delivery. Four mechanisms were identified by both parents and providers: emotional support, information collection and sharing, facilitating communication, and addressing unmet social needs. Parent-level outcomes included improved communication, feeling supported, and increased parental knowledge surrounding the child’s care and the health system. Provider-level outcomes included providing tailored communication and attending to family non-medical needs.

Conclusions:

This study provided insight into the mechanisms by which an inpatient navigation program may improve communication, support, and knowledge for parents of low-income children of color, both directly and by changing provider behavior.

Keywords: Patient Navigation, Low-Income/Minority, Patient-Centered Communication, Emotional Support, Pediatric Hospital Medicine

Introduction

Low-income children of color and their families have worse hospital experiences and outcomes relative to other children. These include increased risk of serious adverse events, increased length of stay (LOS),1 inadequate pain control,2,3 and poor communication between parents and clinicians.4,5 While structural and interpersonal racism and discrimination are the foundational causes of these disparities, research suggests that suboptimal communication and healthcare system complexity contribute to and reinforce them.1,6,7 While addressing the underlying discrimination is essential, few interventions exist to improve experiences and outcomes for these families in the meantime.5–7

Patient navigation programs help patients access, understand, and/or complete needed medical care by addressing logistical and structural barriers to care through partnership with a designated individual who helps identify barriers, propose solutions, and connect the patient with resources.8 Some programs emphasize cultural concordance between patient and navigator, and/or provision of longitudinal support. The navigator’s relationship to other healthcare team members varies by program, but they typically enable others to spend more time performing specialized work (e.g., allowing social workers to spend more time providing mental health counseling rather than coordinating transportation). Navigation programs have demonstrated effectiveness for patients with chronic conditions,9 and navigation targeting social needs has been found to improve child health in outpatient settings.10 There are few studies examining navigation for children, especially in the hospital setting, and none that explicitly include addressing barriers to high-quality care related to the parent-provider interaction, such as communication.

Consequently, we developed an inpatient navigation program for low-income children of color and their parents, The Family Bridge Program (FBP). Our design was informed by a survey,6 focus groups, collaborative workshops including parents, and pilot-tested. This qualitative study evaluates the FBP using interviews with enrolled parents or caregivers and their inpatient healthcare providers, employing a realist evaluation framework.11 Study objectives were to (1) understand the experiences of parents and providers who interacted with the FBP and (2) to refine a program theory by exploring relationships between contexts, program mechanisms, and outcomes from the perspectives of families and providers. We sought to understand how the FBP worked, for whom, and in which contexts, to refine the program and adapt it to new sites.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at Seattle Children’s Hospital, a free-standing, quaternary care facility in Seattle, WA between April and October of 2018. The program was developed over 4 years with input from parents, providers, staff, researchers, administrators, and hospital leaders. It was pilot-tested on the medical unit, which is staffed by unit-specific nurses, social workers, care coordinators, and medical teams. Each of the 4 General Pediatric resident teams is composed of a supervising attending physician; resident physicians, who provide front-line care and are first contacts for families and clinical staff; and medical students. These teams care for inpatients with conditions that do not “belong” to a specific subspecialty service, such as asthma, dehydration, or chronic conditions involving multiple organ systems. The program was designed to flexibly interface with existing support services without duplication, to ensure families were being reliably connected to those services and to address identified gaps related to communication, culture, and emotional support. Only existing hospital- and community-based resources were accessed, beyond the services provided by the Guide herself.

The FBP assisted families during and immediately after a child’s hospital stay. Program activities were delivered by the Family Bridge Guide, a bilingual, bicultural Latina and former medical Spanish interpreter at the same hospital who was hired and trained for this role. Program elements included (1) an orientation to and education about the hospital and medical team structure; (2) an unmet social needs assessment, to identify and address needs such as food insecurity; (3) a communication and cultural preference assessment, to elicit important information regarding communication with the family, such as health literacy; (4) communication coaching with the parent, to clarify and practice asking questions; (5) emotional support, delivered through frequent check-ins; and (6) a follow-up phone call 2–3 days after discharge.12 The Guide communicated with the family in-person, via call and text; and with the medical team via email, pager, chart notes, and rounds attendance when possible. The Guide interpreted for Spanish-speaking parents when present for medical discussions and used a professional interpreter to communicate with Somali-speaking families. In her role, she proactively identified family needs across a range of domains (financial, logistical, communication-related, cultural, emotional), responding to them herself whenever possible and connecting the family to other team members (e.g., social work) when the need required additional expertise.

Participants and Recruitment

After electronic record screening, parents or caregivers (henceforth referred to as ‘parents’) were consented and enrolled at the bedside for participation in the FBP Pilot Study, including the interview. Eligible families included those whose child was admitted to a resident-staffed general pediatric service within the prior three days; whose preferred language for care was English, Spanish, or Somali; who had public or no insurance; and who reported any combination of race and ethnicity besides non-Hispanic white. Preferred language, race and ethnicity were collected at hospital registration. Sixty families enrolled and participated in the study. Providers and staff (attendings, residents, nurses, care coordinators, and social workers) who cared for enrolled families were invited via email to participate in a semi-structured telephone interview.

Data Collection

Patient race and ethnicity, language for care, medical complexity,13 and encounter characteristics were derived from hospital administrative data. Parents reported annual household income on the enrollment survey.

Four to six weeks post-discharge, we conducted a semi-structured interview with parents regarding their experience with the FBP. Parent interviews (n=50) lasted 20–40 minutes, mostly via telephone, and were conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed by trained study staff, both male and female (L.S.G., K.B., H.C.), who were unknown to participants prior to study initiation (interview guide is available from the author on request). Spanish interviews were conducted by a certified bilingual team member (L.S.G.). All interviewers had experience with qualitative research, and the principal investigator reviewed and provided feedback on initial encounters. Both parents who preferred Somali for medical care chose to complete interviews in English. Parents who did not complete the interview (n=10) were considered lost to follow up.

Provider/staff interviews (n=23) lasted 10–30 minutes and were conducted via phone by the principal investigator (K.C.L.), who is an attending physician and known to many of the participants. Interviews elicited perceptions of the program regarding how it impacted patients and workflows, along with suggested improvements. Detailed notes and verbatim quotes were transcribed during each interview given time and resource constraints. Of the sample, 70% were attending physicians. Other interviewees included medical trainees, bedside nurses, and social workers (all referred to as “providers” henceforth).

We sought to interview all parents enrolled in the study and all involved providers, thus did not use data saturation to determine our final sample. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment. All de-identified transcripts were analyzed in Dedoose (version 8.1.21).

Analytic Framework

The Family Bridge Program design was guided by Fishbein’s Integrated Model of Behavior Prediction,14 which states that actions in health care settings are changed by taking into account beliefs and expectations regarding care; equipping individuals with skills to inform those future actions can lead to higher expectations and better care. Interviews were analyzed using a Realist Evaluation framework to better understand which program components produced what reported outcomes, under what circumstances. Realist Evaluation starts with a program theory, then refines it by carefully interrogating the qualitative transcripts to answer the question: ‘What works, for whom, in what circumstances and in what respects, and how?’11 The framework is organized around categories of context, mechanism and outcomes, and facilitates delineation of the relationships between these categories and an understanding of how and for whom a program works. This approach results in a robust program theory that allows for effective revision, tailoring, and adaptation of the program based on a clear understanding of the mechanisms by which it operates. For this study, we operationalized the question of “for whom” the program worked based on attributes mentioned in their interviews, rather than using externally-defined categories (e.g., administratively-defined medical complexity).

Data Analysis

Provider and parent interviews were qualitatively analyzed as separate data sets. For each set, we (H.C., L.S.G, K.B., K.C.L.) free-coded 5 interviews to generate observed themes and create a preliminary codebook, discussing each code in twice-weekly team meetings to reach consensus on meaning and definition. We then undertook several rounds of code testing and refinement, via double-coding of transcripts by multiple team members, followed by group discussion and code revision. This continued until codes were applied consistently between team members; all parent transcripts were double-coded, while the remaining transcripts were single-coded in the provider data set. Spanish transcripts were analyzed in Spanish by certified proficient team members, with selected quotes translated for inclusion in the manuscript.

For synthesis of parent and provider codes, coding memos were used to categorize each into the domains of context, mechanisms, and outcomes. We then mapped connections between these. Relationships were examined, discussed and refined at weekly meetings; and ultimately consolidated into theory diagrams, which were iterated upon until consensus was achieved.

Summary statistics were compiled for patient and parent demographic and clinical data. The Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Parent Interviews

Of 60 families enrolled, 50 (83%) completed the follow-up interview. Sixty-six percent of enrolled children identified as Hispanic and 24% as non-Hispanic Black (Table 1). Preferred language for medical care was predominantly English (60%), followed by Spanish (36%) and Somali (4%). Over half of respondents reported an annual family income of <$30,000.

TABLE 1.

Child and parent characteristics of those who completed follow-up semi-structured interviews.

| Child characteristics | N=50 |

|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity, N (%) | |

| Hispanic | 33 (66%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12 (24%) |

| Asian | 1 (2%) |

| Alaska Native or American Indian | 1 (2%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 1 (2%) |

| Other1 | 2 (4%) |

|

| |

| Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm | |

| Non-chronic | 18 (36%) |

| Non-complex chronic | 14 (28%) |

| Complex chronic | 18 (36%) |

|

| |

| Previous inpatient stay at SCH, N (%) | 14 (28%) |

|

| |

| 30-day inpatient readmission, N (%) | 5 (10%) |

|

| |

| ED Visit within 30 days, N (%) | 6 (12%) |

|

| |

| Previous PICU Stay | 11 (22%) |

|

| |

| Hospital length of stay in days, median (IQR)1 | 2.9 (1.6, 6.2) |

| Parent characteristics | N=50 |

|

| |

| Preferred language for care, N (%) | |

| English | 30 (60%) |

| Spanish | 18 (36%) |

| Somali | 2 (4%) |

|

| |

| Household income in US dollars, N (%) | |

| <15,000 | 11 (22%) |

| 15–30,000 | 15 (30%) |

| >30,000 | 13 (26%) |

| Unsure/Declined to answer | 11 (22%) |

|

| |

| SCH—Seattle Children’s Hospital PICU—Pediatric intensive care unit | |

”Other” is reported if that was the category selected by respondents

IQR—Interquartile range

Contexts

Parents identified four contextual factors that influenced program relevance and effect (Figure 1). Parents found the FBP most helpful when the timing of intervention delivery occurred early in their hospital stay, which enabled them to use the tools more fully, and when current and past clinical experiences were negative or few. Additionally, parents reported that the FBP was most relevant when barriers to communication, such as language or lack of familiarity with medical terminology, existed; also when parents identified limited access to resources, ranging from transportation, to food insecurity, to lack of social support (see Table 2 for interview excerpts).

Figure 1.

Parent Program Thory

This figure describes the program theory developed from interviews of enrolled parents. Arrows represent a relationship between a context that rendered a mechanism relevant for families, and the reported outcome associated with that mechanism. This diagram depicts only the ways in which parents reported that the program did work, not the ways in which it did not.

Table 2:

Parent interview excerpts to illustrate domains of Realist Evaluation framework

| Contexts | |

|---|---|

| Current and Past Clinical Experiences | Really, the program was good. It helps a lot of people who come for the first time-especially for the first time--and who don’t know much about hospitals. (Parent 34, Spanish) |

| Barriers to Communication | Sometimes, maybe we have a misunderstanding, or the way [the doctors] understand the issue is different from the way I understand the issue, because I am the parent, not the doctor. (Parent 59, English) |

| Access to Resources | The first day that [the Guide] met me, I did the survey, and I told her, you know, what I was having trouble with, and she came back with resources immediately. (Parent 02, English) |

| Timing of Intervention Delivery | Knowing [about resources] from the beginning would have been really, really helpful. ‘Cuz even worrying, you know, about where am I going to go get food and that kind of thing, that’s pretty stressful when you’re in here. (Parent 01, English) |

| Mechanisms | |

| Emotional Support | [The Guide] was really amazing…Anybody could be comfortable around her…You know, someone who I can talk to. (Parent 24, English) |

| Information Collection & Sharing | Sometimes I didn’t understand something and was left feeling unsure … I would tell [the Guide] and she would tell the doctors or nurses. (Parent 14, Spanish) |

| Facilitating Communication | If I had any questions, I could just put them on the whiteboard that they had there.…Then the next day when *the doctors+ come for rounds, they already know my concerns. (Parent 10, Spanish) |

| Addressing Unmet Social Needs | It does help, you know, to have someone…look after your needs and make sure they’re met, ‘cuz it’s just so chaotic when you’re here… Just having someone making sure that you have food, and resources, ‘cuz you just forget. (Parent 01, English) |

| Enhanced Familiarity with Hospital Environment | Well, she helped me by telling me where everything was, looking in to it if I wanted money for food…the laundromat, soap, toothbrush, and all of that, clothing if we needed it. (Parent 18, Spanish) |

| Outcomes | |

| Improved Communication Skills |

I just felt confident saying it myself, you know, ‘How’s my son?’, ‘What’s his condition look like?’, ‘What’s best for the child?’… [The doctors were] more interested in what I had to say – I felt like I had a lot of knowledge, after all, as a mom. (Parent 24, English) |

| Feeling Supported in the Care Environment | I felt very lonely because it was just me and my kid. And then [the Guide] came and talked with me about not feeling bad, and that was how I felt her support. And then she told me of the type of help that is available there from the hospital. (Parent 49, Spanish) |

| Increased Knowledge, Skills, and Understanding | She shared our concerns with the doctor... And then the doctor came back and explained her thinking to help us understand her overall thinking and gave us a bigger picture. (Parent 44, English) |

| Improved Knowledge of Healthcare System and Resources | I liked the program because for the next time that I am at the hospital I will already know about what I can do or ask, or to ask for an interpreter. (Parent 10, Spanish) |

Mechanisms

Parent interviews elicited five primary mechanisms by which the FBP led to outcomes, illustrating how they felt the program worked. Parents recalled the Guide serving as a reliable source of emotional support and helping to address unmet social needs, both of which enabled them to focus on their child’s care. Additionally, parents reported that the FBP programming enhanced familiarity with the hospital environment by detailing hospital resources available to parents during their stay and providing information on daily hospital life, which increased confidence by reducing unknowns.

Parents also identified the Guide’s activities of information collection and sharing between the family and the medical team as an important mechanism by which hospital experience was improved given the emphasis on communicating detailed information. In a similar yet distinct group of activities, which we understood as facilitating communication, parents described promotion of open conversation with care providers and new communication skills and confidence that could be carried beyond the current hospitalization. Parents recalled the Guide practicing communication techniques, offering coaching with regard to asking questions of the medical team, and interpreting for Spanish-speaking families.

Outcomes

Parents identified four outcomes from FBP participation, two of which described ways in which their immediate experience was modified, and two that extended to future encounters. First, parents described improved communication as the FBP prepared them to express concerns, which contributed to care plans and communication tailored for their specific needs. Parents also describe feeling supported in the care environment, through the provision of emotional support and addressing needs, particularly in the context of prior negative experiences or greater unmet social need.

Second, parents described program outcomes interrelated with perceived improvements in communication and feelings of support, but distinct with respect to learnings applicable in other settings. Parents described increased knowledge, skills and understanding, from engaging in their child’s care and with receptive clinicians; and improved knowledge of the healthcare system and available resources, as well as increased comfort in the hospital environment relative to any prior experiences. The outcome of improved communication facilitated increased knowledge, especially for parents who preferred Spanish or Somali languages. Increased understanding further improved communication, as parents were better able to know which questions to ask and concerns to voice.

Suggestions for Improvement

Most parents reported no suggestions for improvement and reiterated having liked everything about the program. Some parents suggested that connecting with the Guide earlier in the hospital stay, rather than a few days in, would have helped them know about available resources sooner. Other suggestions included offering resources to siblings and other non-parent family, especially for those who travelled long distances; providing a recording of conversations; and continuing to follow families in outpatient clinics.

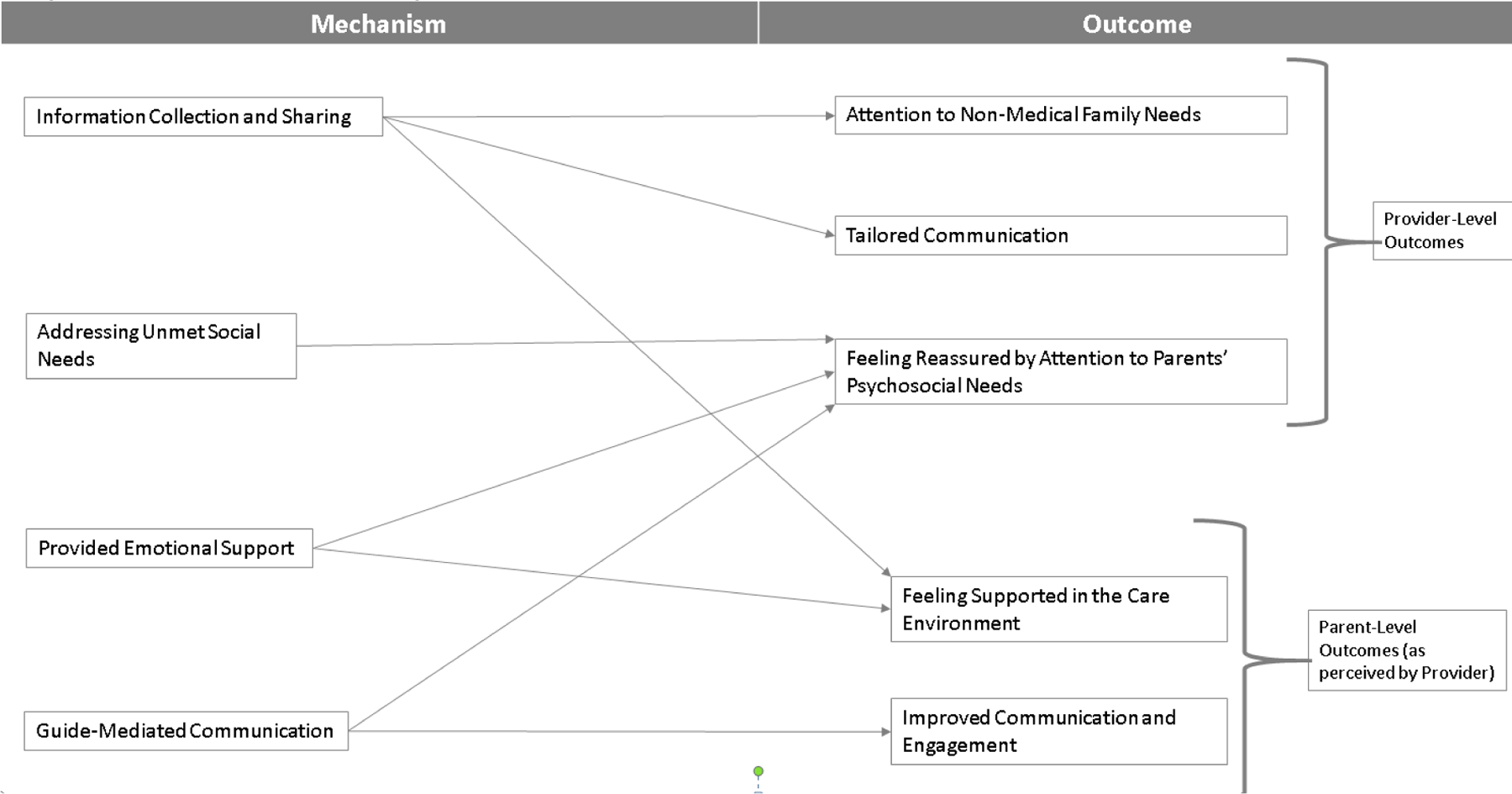

Provider Interviews

Twenty-three hospital-based providers completed an interview concerning their experience with the FBP. In analyzing the interviews, we sought to understand how providers felt that the program was working for both families and themselves (mechanisms), and what outcomes resulted. Given the more limited sample, we did not identify consistent contexts from provider interviews (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Provider Program Theory

This figure represents the reactions to program elements as described by providers, and their perception of how the same program elements impacted caregivers.

Mechanisms

Like parents, providers noted how the Guide’s participation in information collection and sharing was an important part of how the FBP worked. Through participating in family-centered rounds, and serving as an interpreter for Spanish-speaking families, Guide-mediated communication bridged gaps in understanding by eliciting and sharing detail that providers didn’t have time to gather through usual pathways, but which influenced engagement with the family. Providers also expressed relief and appreciation for the FBP’s proactive approach to addressing unmet social needs; including helping families to navigate challenging moments when the Guide provided emotional support by spending time that providers felt they did not have (see Table 3 for interview excerpts).

Table 3:

Provider Interview excerpts to illustrate domains of Realist Evaluation framework

| Mechanisms | |

|---|---|

| Information Collection & Sharing | We think we’re doing a great job but the family has no idea what’s going on. [Getting information from the Guide] personally changed how I was communicating with the family, and I made sure the rest of the team was using that too. (Provider 2, Attending) |

| Addressing Unmet Social Needs | [The Guide] uncovered some housing insecurity and transportation needs for this family. So when we were planning discharge, it really helped us understand what would be needed to get the family home safely.(Provider 5, Social Work) |

| Provided Emotional Support | It was a non-ideal clinical situation, and we wanted to give more info than we had. So it was really nice to have someone taking the more holistic and thoughtful approach…that supportive help. … There was just so much going on that the rest of us didn’t have a lot of capacity to take on. (Provider 16, Attending) |

| Guide-Mediated Communication | I thought the dynamic on rounds was really great, and I thought it was really great to have a parental cheerleader there on rounds. (Provider 15, Resident) |

| Outcomes | |

| Attention to Non-Medical Family Needs | It’s telling that we need the program…Parents don’t know about the pathway and steroids, but they’re worried about food and transportation. It’s awareness [for us] regarding that. (Provider 17, Attending) |

| Tailored communication | The email [from the Guide] provided a lot more information that made me realize I needed to go back and talk more with the mom about the things that had been brought up with the Guide. (Provider 15, Resident) |

| Feeling Reassured by Attention to Parents’ Psychosocial Needs | It was hard to feel like we were doing a good job with them on a not-busy day, so almost impossible to do a good job on a busy day. So knowing someone else was walking this walk with them was really great. (Provider 16, Attending) |

| Feeling Supported in the Care Environment | I also really appreciated how much the family said they felt supported. And this was a kid with a lot of cooks in the kitchen, so many specialties, but no one was really providing wrap around services and figuring out what the family needed and how they are coping. (Provider 5, Social Work) |

| Improved Communication and Engagement | [This was] a patient who didn’t have a diagnosis…pretty sick, the family had a lot of social issues… *They were+ not used to having a lot of doctors involved, so [the Guide] really helped navigate them through the process, helped us know how to communicate with them. (Provider 18, Attending) |

Outcomes

Provider interviews revealed five perceived outcomes of the FBP, three of which related to providers themselves, and two which they noted in enrolled families.

Provider-level outcomes highlighted reductions in provider stress, and reconsideration of usual interaction patterns. Providers noted that learning family communication preferences through the Guide’s evaluations drew attention to non-medical family needs, and encouraged them to reconsider usual interactions resulting in tailored communication to meet families’ specific circumstances. Providers reported feeling reassured by attention to parents’ psychosocial needs, specifically that having someone whose explicit goal was to attend to parents’ psychosocial well-being resulted in one less concern for the medical team. Having such needs assessed and communicated early allowed for an organized and coordinated response, decreasing provider stress.

Providers observed parent-level outcomes of FBP participation with regard to communication style and perceived feelings of support. Providers felt that the Guide tended to families’ emotional needs which resulted in families feeling supported in the care environment. Separately, providers reported increased parental confidence to voice concerns via the Guide’s reminders that they had relevant, important details to share about their child, which providers observed as feelings of validation and ultimately improved communication and engagement with the team.

Suggestions for Improvement

Provider feedback focused on how the information collected by the Guide was shared, and how to best incorporate those communications into already-busy workflows. Discussion of who should receive communications (attending, resident, nurse) and mode of communication (pager, email, chart note, or face-to-face) dominated responses, with no clear consensus. Other suggestions included further integration with other hospital services, and (similar to parent suggestions) initiating program screening and enrollment early in the hospital stay.

Discussion

Application of a modified Realist Evaluation approach helped us understand mechanisms by which the FBP improved hospital outcomes for low-income children of color and their families. Based on parent and provider interviews, the FBP’s primary mechanisms included interpersonal emotional support, facilitating communication in direct and indirect ways, assisting with unmet social needs, and enhancing parent knowledge about the hospital and healthcare system. These mechanisms led to parent outcomes of improved communication, increased knowledge of both their child’s condition and the healthcare system, and feeling supported; and provider outcomes of improved tailoring of communication to the individual family and feeling reassured. Suggested improvement included program delivery earlier in the hospital stay.

The existing pediatric patient navigation literature is limited, largely focused on the outpatient setting and specific disease processes.10,15–18 The FBP is unique in its inpatient focus and inclusion of pediatric patients regardless of diagnosis. Nonetheless, several of the FBP’s identified mechanisms are commonly found in the adult and/or pediatric patient navigation literature.19–22 Many navigation programs address unmet social needs, as those needs frequently pose the barriers to care that navigation seeks to address.10,22,23 However, rather than focusing only on needs that interfered directly with accessing medical care (e.g., transportation), the FBP proactively assisted with a broad range of needs, from food and housing to education, that may not have been actively impeding the child’s care, but may have been causing stress to parents thus interfering with their ability to engage.

Many other programs also feature a navigator who collects and shares information between the patient and the medical team.20 However, most programs do not emphasize empowerment, advocacy, or communication coaching for parents, to help them express their questions and concerns and thereby elicit better communication from providers.23,24 In our study, this was identified as a key programmatic element by both parents and providers. Given that better communication is associated with better health outcomes,25 this represents a novel addition to patient navigation that has the potential to reduce disparities across racial and socioeconomic lines. Our study also builds upon prior evidence that identified the navigator as crucial to the flow of communication,19 by delineating how assessing and sharing social and cultural information within the medical team can improve provider-reported tailoring of their interactions and communication to family needs.

Patient navigation programs generally focus on individual barrier reduction rather than emotional support22; however, emotional support may be an implicit rather than explicit program component in many.20 For example, when programs work with patients to address cancer-related fear and emotions, they are providing emotional support.22 According to parents and providers in our interviews, emotional support emerged as a clear mechanism by which the FBP achieved positive outcomes, suggesting it as an important component of navigation that warrants more explicit future study.

The FBP was developed as a stand-alone program that could interface flexibly with existing social support and care coordination programs in the inpatient and community settings. As such, we expect that the FBP or similar program could be adapted to a large range of local contexts. Beyond informing program adoption, our results could also be seen as illuminating the activities that lead to improved care delivery from both parent and provider perspectives: detailed, sensitively-collected information about families’ needs and preferences; more emotional and concrete support for families; communication coaching for parents; and more tailored communication from providers. Even in the absence of a formal program, these things could be implemented by individual providers or clinical groups to improve care delivery for families of low-income children of color.

Future research should examine the extent to which brief multi-faceted navigation programs like FBP influence patient, family, and provider outcomes, using validated survey measures and direct observation. Examining effects on bias, discrimination, and disparate outcomes are of particular relevance. It is important to understand the relative contribution to overall outcomes of individual program components to inform future tailoring to new cultural groups and settings. In particular, given how important emotional support was to both parents and providers in our study, more research on how this influences health outcomes is needed; very little exists at present.

Limitations of the study include overweighting English and Spanish-speaking families in enrollment (96%), and that the majority of providers being attending physicians (70%). Parent interviews were conducted 4–6 weeks after hospital discharge, so recall bias may have influenced our findings; however, because a child’s hospitalization is a stressful event for parents, we expect reasonable recall of salient experiences within this time frame.26 Additionally, coding was done to capture aspects of the FBP. Thus, absence of comment on certain hospital experiences does not mean the element itself was absent. As is true with all qualitative studies, results reflect the experiences and opinions of a particular group of individuals, and are not necessarily representative of others. However, we interviewed the majority of parent participants in the FBP, so we expect our results are reflective of this group of pilot participants.

Conclusion

Overall, parents and providers reported positive experiences with the Family Bridge Program. The program provided parents with emotional support, orientation to the hospital environment, connection to resources, and assistance with communication; yielding improved communication, feelings of support, knowledge, and skills. Providers noted the program offered important information about the family, along with support, resources, and in-person communication facilitation to parents; allowing providers to offer what they perceived to be better medical care. The model of brief, inpatient-focused patient navigation developed for the FBP holds promise for addressing persistent disparities in hospital experiences and outcomes experienced by low-income children of color and their families.

What’s New:

In this qualitative evaluation, we delineate the contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes by which an inpatient-focused patient navigation program for structurally marginalized families can improve parental support and understanding while also prompting more tailored provider behavior and communication.

Funding Sources:

This work was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant K23 HD078507 (PI Lion). Ms. Chisholm’s time was supported by Yale School of Public Health Summer Internship stipend. The funding sources had no role in the conduct of the research or the preparation of the article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03599674

References

- 1.Lion KC, Rafton SA, Shafii J, et al. Association Between Language, Serious Adverse Events, and Length of Stay Among Hospitalized Children. Hospital Pediatrics 2013;3(3):219–225. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2012-0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jimenez N, Jackson DL, Zhou C, Ayala NC, Ebel BE. Postoperative pain management in children, parental English proficiency, and access to interpretation. Hosp Pediatr 2014;4(1):23–30. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2013-0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med 2019;37(9):1770–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics 2005;116(3):575–579. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan A, Yin HS, Brach C, et al. Association Between Parent Comfort With English and Adverse Events Among Hospitalized Children. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174(12):e203215. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lion K Casey L, Zhou C, Ebel BE, Penfold R, Mangione-Smith R. Identifying Modifiable Health Care Barriers to Improve Health Equity for Hospitalized Children. Hosp Pediatr 2019;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2019-0096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flores G, Committee On Pediatric Research. Technical report--racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics 2010;125(4):e979–e1020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. The History and Principles of Patient Navigation. Cancer 2011;117(15 0):3539–3542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McBrien KA, Ivers N, Barnieh L, et al. Patient navigators for people with chronic disease: A systematic review. PLoS One 2018;13(2). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of Social Needs Screening and In-Person Service Navigation on Child Health: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170(11):e162521. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lion K, Arthur K, Sotelo Guerra L, et al. Development and Pilot-Testing of an Inpatient Navigation Program for Families of Vulnerable Children Presented at the: Pediatric Academic Societies 2019 Meeting; April 30, 2019; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and Validation of the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA) Version 3.0. Acad Pediatr 2018;18(5):577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishbein M An integrative model for behavioral prediction and its application to health promotion. In: Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research, 2nd Ed. Jossey-Bass; 2009:215–234. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantell MS, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of In-Person Navigation to Address Family Social Needs on Child Health Care Utilization: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open 2020;3(6):e206445–e206445. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krantz C, Hynes M, DesLauriers A, et al. Helping Families Thrive: Co-Designing a Program to Support Parents of Children with Medical Complexity. Healthc Q 2021;24(2):40–46. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2021.26547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirk J, Jespersen J, McKillop S. Early Psychosocial Contact for Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with Cancer: The Impact of the AYA Oncology Navigator. Journal of adolescent and young adult oncology Published online 2021. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2021.0036 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Wagner C, Zimmerman CE, Barrero C, et al. Reduced Socioeconomic Disparities in Cleft Care After Implementing a Cleft Nurse Navigator Program. Cleft Palate Craniofac J Published online April 7, 2021:10556656211005646. doi: 10.1177/10556656211005646 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Gunn C, Battaglia TA, Parker VA, et al. What Makes Patient Navigation Most Effective: Defining Useful Tasks and Networks. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 2017;28(2):663–676. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients. Cancer 2005;104(4):848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh J, Young JM, Harrison JD, et al. What is important in cancer care coordination? A qualitative investigation. European Journal of Cancer Care 2011;20(2):220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient Navigation: An Update on the State of the Science. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61(4):237–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb LM, Adler NE, Wing H, et al. Effects of In-Person Assistance vs Personalized Written Resources About Social Services on Household Social Risks and Child and Caregiver Health: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(3):e200701. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luke A, Doucet S, Azar R. Paediatric patient navigation models of care in Canada: An environmental scan. Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(3):e46–e55. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(2):146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummings P Ability of parents to recall the injuries of their young children. Injury Prevention 2005;11(1):43–47. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.006833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]