Abstract

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is quite prevalent in low- and middle-income countries, and has been proposed to increase the risk of depression. There is only a prior study assessing antenatal depression among the subjects with GDM in the Bangladesh, which leads this study to be investigated.

Objective

To determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms and potential associations among pregnant women diagnosed with GDM.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out among 105 pregnant women diagnosed with GDM over the period of January to December 2017 in 4- hospitals located in two different cities (Dhaka and Barisal). A semi-structured questionnaire was developed consisting of items related to socio-demographics, reproductive health history, diabetes, anthropometrics, and depression.

Results

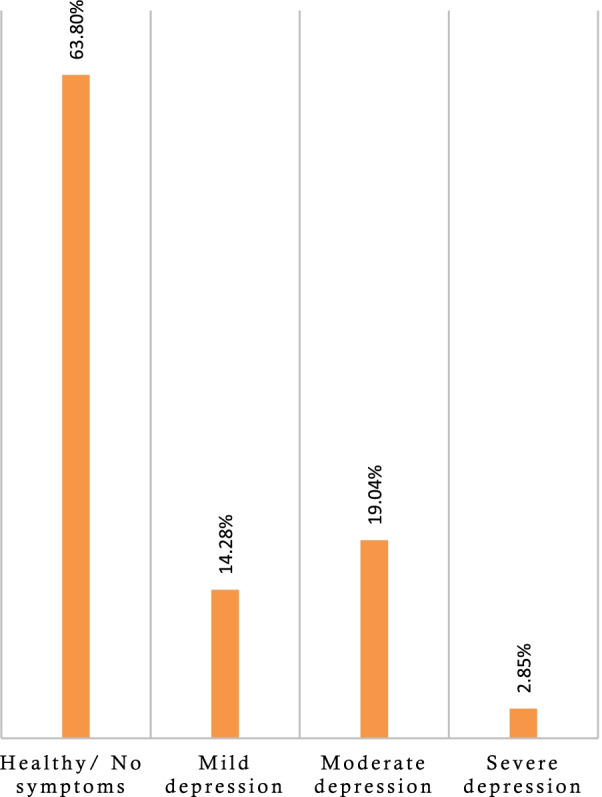

Mild to severe antenatal depression was present in 36.2% of the subjects (i.e., 14.3%, 19% and 2.9% for mild, moderate and severe depression, respectively). None of the socio-demographic factors were associated with depression, but the history of reproductive health-related issues (i.e., abortion, neonatal death) and uncontrolled glycemic status were associated with the increased risk of depressive disorders.

Conclusions

GDM is associated with a high prevalence of depressive symptoms, which is enhanced by poor diabetes control. Thus, in women presenting with GDM, screening for depression should be pursued and treated as needed.

Keywords: Antenatal depression, Body mass index, Diabetes and depression, Gestational diabetes mellitus, Maternal depression, Pregnancy and depression, Reproductive health

Plain English Summary

Pregnancy is a highly stressful period in a woman's life that can also be associated with mental health problems such as depression. Depression is reported in about 16% of pregnant women whereas and such prevalence can double in LMICs (e.g., Bangladesh). In addition, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has emerged as a common condition affecting approximately 10% of all pregnancies. GDM has also been associated with adverse mental health outcomes, particularly depression. GDM women with antenatal depression are not only at increased risk of poorer quality of life, but are also at increased risk of adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes, particularly in LMIC. This study investigates the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Bangladeshi pregnant women diagnosed with GDM. It is found that depression was detectable in 36.2% subjects. In addition, a history of reproductive health-related issues (i.e., abortion, neonatal death) and uncontrolled glycemic status were associated with increased risk of depressive disorders. Considering the negative effects of both GDM and depression on pregnancy-related outcomes, early screening of these conditions should be pursued, preferably once every trimester over the duration of the pregnancy.

Introduction

Pregnancy is a highly stressful time in a woman's life and is often associated with anxiety and depression. Fear of fetal deformities, economic concerns, and motherhood expectations are the common sources of anxiety that may ultimately lead to depression [1]. According to the WHO, the prevalence of depression in developing countries is around 15.6% during pregnancy [2]. However, a systematic review of studies conducted in developed and low-income countries reported the prevalence of gestational depression as ranging between 5 to 30% for developed economies [1, 3, 4] and 15.6% to 31.1% for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like Bangladesh [5]. These estimates varied according to ethnicity, history of miscarriage, issues related to medically assisted pregnancy, ambivalent attitude about the pregnancy, and socioeconomic condition of the women [1, 3, 5–7]. Depression is an abnormal psychological state that is usually characterized by excessive or long-term decreased mood and loss of interest in enjoyable activities, and reduced quality of life [8, 9], all of which can lead to a vast array of pernicious consequences for both mother and child.

In recent years, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has emerged as a common condition during pregnancy [10]. Indeed, one in 10 pregnancies is estimated to be associated with diabetes, whereas 90% of these cases are reported as GDM [11, 12]. Furthermore, the risk of GDM can rise to 30% of all pregnancies if obesity is present [11], with the majority of cases (87%) being reported from LMIC [12]. The prevalence of GDM has been progressively increasing in Bangladesh compared to other South-East Asian countries [13], with pooled estimates indicating a prevalence of about 8.0% [14–16]. The presence of GDM increases the risk of adverse effects on both the mother and child. The most common complications include an increased risk of fetal loss as well as postpartum development of type 2 diabetes in the mother [11, 17, 18].

GDM has also been associated with adverse mental health outcomes, particularly depression. GDM subjects with antenatal depression are not only at increased risk of poorer quality of life [19], but are also at increased risk of adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes, particularly in LMICs [20–22]. Considering the potential negative consequences of GDM and gestational depression and the scarcity of information regarding these issues in Bangladesh [23], the present study was undertaken to investigate the prevalence of depressive symptoms and potential associations among Bangladeshi pregnant women diagnosed with GDM.

Methods

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the prevalence of depressive symptoms and potential associations among Bangladeshi pregnant women diagnosed with GDM within January to December 2017 in two different cities (Dhaka and Barisal). Two hospitals from each city were included based on the criteria of having adequate facilities to deal with GDM patients and availability of patients seeking medical assistance from remote areas and those who had GDM-related complications. Therefore, it is assumed that the vast majority, if not all pregnant women who were at risk, suspected to suffer from GDM, or those formally diagnosed as GDM patients would come to these hospitals for their treatment and antenatal check-ups. The survey was carried out in the outpatient departments of the four hospitals, namely (i) BIRDEM General Hospital (Dhaka), (ii) BSMMU Hospital (Dhaka), (iii) Sher E Bangla Medical College Hospital (Barisal), and (iv) Advocate Hemayet Uddin Ahmed Diabetic & General Hospital (Barisal).

Data collection approach

Before the onset of the data acquisition interviews, the semi-structured questionnaire was pilot tested on a total of 10 respondents to ascertain it was easily understandable by all interviewees. After implementing changes based on the feedback from the pre-testing phase, data were collected from the respondents through face-to-face interviews conducted in Bangla, the native language of both the research team and the participants. However, respondents were identified by purposive sampling after compiling selection criteria, which included: (i) pregnant women diagnosed with GDM by the hospital physician and (ii) women who were willing to participate. Participants were excluded from the study if they (i) had pre-gestational diabetes and comorbid conditions, (ii) were severely ill or unable to participate, or (iii) were not willing to participate. A total of 105 interviews were ultimately included for analyses.

Ethical considerations

A formal ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the National Institute of Preventive and Social Medicine, Dhaka, Bangladesh (ethical clearance approval number: NIPSOM/IRB/2017/245). Participation in this study was absolutely voluntary. Potential subjects were informed that they have the right to refuse to respond to any of the entire set of interview questions and that they also have the right to withdraw from an ongoing interview. Subjects were also clearly informed about the confidentiality of their data and provided complete assurance that all information would be kept confidential and their names or anything which can identify them would not be published or exposed anywhere. Participants had to provide consent by signature or thumb impression.

Measures

A semi-structured questionnaire was developed in Bangla consisting of questions related to (i) socio-demographics, (ii) reproductive health, (iii) diabetes, (iv) anthropometrics, and (iv) depression. Permission for using the depression assessment instrument was granted by the developer of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). A short description of all variables included in this study is given below.

Socio-demographic factors

The basic socio-demographic information of the participants, such as age, residence, religion, family type, family income, family expenditure, occupation, and education, were documented. In addition, the occupation and education of the participants’ spouses were explored.

Reproductive Health-related factors

Data on reproductive health-related issues such as the age of marriage, duration of married status, age of first pregnancy, the total number of pregnancies, total number of children, age of the last child born, etc., were collected. In addition, a history of (i) intrauterine death, (ii) abortion, (iii) dilation and curettage, and (iv) neonatal death was obtained. Subsequently, a continuous variable was created, compiling all the history-related variables.

Diabetes-related factors

A number of factors associated with GDM were collected in this study. First of all, the history of GDM diagnosis and hypertension in the past pregnancy was assessed. Furthermore, family history of diabetes, personal history of hypertension, and status of smoking and smokeless tobacco use were asked. The aforementioned variables were compiled to create a continuous variable on GDM related issues.

Glycemic status

To evaluate GDM glycemic control or the current use of glucose-lowering medications [24], recently diagnosed glycemic status data were collected from the participants’ patient charts. Based on the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria [25], GDM participants were classified to ‘no control of diabetes’ based on their blood glucose (BG) levels (i) fasting: ≥ 5.3 mmol/l, or (ii) 2 h after breakfast (ABF): ≥ 8.6 mmol/l.

Anthropometric measures

Measurements of the height and weight of the participants were performed. For assessing body mass index (BMI), weight in kilos was divided by the square of height in meters. The research assistants measured height and weight. The participants' weight was measured with a digital scale with an accuracy of 0.1 kg; with participants having on light clothing and without shoes. The digital weighing scale measurement accuracy was checked at various stages using standard weights. The height of the participants was measured using a tape with an accuracy of 0.1 cm that was fixed to the wall with a special tool in the different clinics. The participants took off their shoes and heels; buttocks, shoulders, and back of the head touched the wall, and the Frankfort line was parallel to the ground. Later on, the recommended BMI categories were followed: (i) < 18.5 kg/m2 = underweight, (ii) 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 = normal or healthy weight, (iii) 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 = overweight, and (iv) ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 = obese [26].

Depression scale

Depression was assessed by the 10-item MADRS [27]. Since its development, the scale has been widely validated and used globally, including in Bangladesh [28, 29] and has also been used in GDM patients [23]. The scale contains symptoms related to (i) apparent sadness, (ii) reported sadness, (iii) inner tension, (iv) reduced sleep, (v) reduced appetite, (vi) concentration difficulties, (vii) lassitude, (viii) inability to feel, (ix) pessimistic thoughts, and (x) suicidal thoughts [27]. Based on the five-point Likert scale (0 to 6), the total score of the scale ranges from 0 to 60 points. Like in previous studies [23, 28, 30], the MADRS scores are categorized into 4 groups, healthy (0–12 points), mild depression (13–19 points), moderate depression (20–34 points) and severe depression (35–60 points) [27].

Statistical analysis

After data collection, individual questionnaires were edited for completion and consistency. Only fully completed questionnaires were entered into the statistical software (SPSS 22, IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis. Descriptive statistics (e.g., percentage, frequencies, mean and standard deviations) were used to describe the data. Inferential statistics (e.g., ANOVA tests, independent t-tests, etc.) were performed to identify significant associations of the studied variables with depression as the outcome variable. A two-tailed p-value of < 0.05 and 95% confidence interval was considered statistically significant.

Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1, whereas Tables 2 and 3 show reproductive health history and GDM-related variables, respectively. Of the 105 women with GDM, 60.0% were in the 26–33-year-old group, and their mean age was 28.98 (± 4.87) years. Most of them were Muslim (88.6%), urban residents (75.2%), and housewives (67.6%) (Table 1). Only 25 women reported having a personal monthly income (42,000 ± 17,795 BDT). The mean total family income of the participants was 57,028 ± 33,860 BDT, whereas 26,400 ± 13,945 BDT was the average reported monthly expenditure (Table 4). About 36.2% of the subjects with GDM reported suffering from mild to severe levels of depression (Fig. 1). However, bivariate analyses showed no significant associations between socio-demographic factors and depression levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the Socio-demographic variables with depression

| Variables | Total sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean | SD | f/t-value | p-value | |

| Age group | |||||

| 18–25 years | 23; 21.9% | 12.78 | 8.61 | 0.265 | 0.768 |

| 26–33 years | 63; 60.0% | 12.83 | 9.51 | ||

| 34–41 years | 19; 18.1% | 11.16 | 7.40 | ||

| Religion | |||||

| Muslim | 93; 88.6% | 12.06 | 8.91 | 2.091 | 0.151 |

| Hindu | 12; 11.4% | 16.00 | 8.57 | ||

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 79; 75.2% | 12.63 | 9.13 | 0.056 | 0.814 |

| Rural | 26; 24.8% | 12.15 | 8.41 | ||

| Family type | |||||

| Joint | 43; 41.0% | 12.93 | 8.39 | 0.157 | 0.693 |

| Nuclear | 62; 59.0% | 12.22 | 9.32 | ||

| Education | |||||

| Up to primary | 21; 20.0% | 14.00 | 10.18 | 0.365 | 0.695 |

| Secondary | 40; 38.1% | 12.25 | 7.57 | ||

| Higher | 44; 41.9% | 12.04 | 9.53 | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Housewife | 71; 67.6% | 12.45 | 8.47 | 0.480 | 0.620 |

| Service holder | 14; 13.3% | 10.86 | 9.47 | ||

| Others | 20; 19.0% | 13.90 | 10.29 | ||

| Husband’s education | |||||

| Up to primary | 7; 6.7% | 11.71 | 7.95 | 0.938 | 0.395 |

| Secondary | 30; 28.6% | 14.40 | 10.09 | ||

| Higher | 68; 64.8% | 11.76 | 8.45 | ||

| Husband’s occupation | |||||

| Service holder | 43; 41.0% | 12.65 | 9.41 | 2.441 | 0.069 |

| Business man | 31; 29.5% | 15.29 | 8.76 | ||

| Stay in abroad | 12; 11.4% | 8.00 | 5.12 | ||

| Day labor | 19; 18.1% | 10.53 | 8.84 | ||

Table 2.

Distribution of the reproductive health-related variables and association with depression

| Variables | Total sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean | SD | f/t-value | p-value | |

| History of intrauterine death | |||||

| No | 100; 95.2% | 12.38 | 8.95 | 0.474 | 0.493 |

| Yes | 5; 4.8% | 15.20 | 8.79 | ||

| History of abortion | |||||

| No | 74; 70.5% | 11.27 | 8.49 | 5.067 | 0.027 |

| Yes | 31; 29.5% | 15.48 | 9.34 | ||

| History of dilation and curettage | |||||

| No | 89; 84.8% | 12.02 | 8.57 | 1.790 | 0.184 |

| Yes | 16; 15.2% | 15.25 | 10.55 | ||

| History of neonatal death | |||||

| No | 93; 88.6% | 11.76 | 8.33 | 6.048 | 0.016 |

| Yes | 12; 11.4% | 18.33 | 11.37 | ||

Table 3.

Distribution of the diabetes-related variables and association with depression

| Variables | Total sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean | SD | F/t-value | p-value | |

| History of GDM in past pregnancy | |||||

| No | 76; 72.4% | 12.68 | 9.14 | 0.099 | 0.754 |

| Yes | 29; 27.6% | 12.07 | 8.44 | ||

| Family history diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 39; 37.1% | 11.95 | 8.48 | 0.248 | 0.620 |

| Yes | 66; 62.9% | 12.85 | 9.22 | ||

| History of hypertension | |||||

| No | 91; 86.7% | 12.59 | 8.95 | 0.053 | 0.818 |

| Yes | 14; 13.3% | 12.00 | 9.05 | ||

| History of hypertension in past pregnancy | |||||

| No | 100; 95.2% | 12.58 | 8.92 | 0.113 | 0.737 |

| Yes | 5; 4.8% | 11.20 | 9.86 | ||

| Family history of hypertension | |||||

| No | 58; 55.2% | 12.03 | 8.41 | 0.373 | 0.543 |

| Yes | 47; 44.8% | 13.11 | 9.57 | ||

| Glycemic status | |||||

| Both fasting and 2 h ABF BG level are in control | 16; 15.2% | 9.38 | 5.30 | 22.403 | < 0.001 |

| Either fasting or 2 h ABF BG level is in control | 48; 45.7% | 8.33 | 5.04 | ||

| Both fasting and 2 h ABF BG level are not in control | 41; 39.0% | 18.49 | 9.98 | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | |||||

| Normal | 23; 21.9% | 12.00 | 7.38 | 0.100 | 0.905 |

| Overweight | 44; 41.9% | 12.95 | 9.03 | ||

| Obesity | 38; 36.2% | 12.32 | 9.79 | ||

Table 4.

Correlations of the continuous variables with depression

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Correlation coefficient (r) | 2-tailed Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28.98 ± 4.87 | − 0.085 | 0.390 |

| Monthly personal income | 42,000.00 ± 17,795.13 | 0.074 | 0.726 |

| Monthly family income | 57,028.57 ± 33,860.14 | 0.017 | 0.862 |

| Monthly family expenditure | 26,400.00 ± 13,945.53 | 0.033 | 0.740 |

| Age at marriage | 21.49 ± 4.339 | − 0.019 | 0.844 |

| Marriage duration | 7.58 ± 5.31 | -0.067 | 0.497 |

| Age of first conceive | 23.54 ± 5.31 | 0.087 | 0.375 |

| Total number of conceive | 2.40 ± 1.31 | − 0.203 | 0.138 |

| Total number of children | 1.64 ± 0.85 | 0.039 | 0.775 |

| Age of last children | 5.96 ± 3.53 | 0.001 | 0.994 |

| Total reproductive health related history | 0.61 ± 0.75 | 0.314 | < 0.001 |

| Total diabetes related history | 1.53 ± 1.07 | 0.023 | 0.814 |

| Fasting blood glucose level | 5.91 ± 1.34 | 0.088 | 0.373 |

| 2 h after breakfast glucose (AFB) level | 8.52 ± 2.29 | 0.271 | 0.005 |

| Both fasting and 2 h AFB glucose level | 14.43 ± 3.08 | 0.239 | 0.014 |

| Body mass index | 28.95 ± 4.91 | − 0.061 | 0.533 |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the depression of the subjects with GDM

Among the participants, 4.8% had a history of intrauterine death, whereas 29.5%, 15.2%, and 11.4% reported a history of abortion, dilation and curettage, and neonatal death, respectively. Subjects reporting a history of abortion and neonatal death were significantly more likely to suffer from depression (f = 5.07, p = 0.027 and f = 6.05, p = 0.016, respectively) (Table 2). In addition, 0.61 (± 0.75) was the mean score of total reproductive health-related history, which was also significantly correlated with depression (r = 0.314, p < 0.001) (Tables 2, 4).

About 27.6% and 4.8% of the subjects were diagnosed with GDM and hypertension in their prior pregnancy, respectively, and 13.3% reported suffering from hypertension during the non-pregnant period. Similarly, 62.9% and 44.8% reported that someone in their family had suffered from diabetes mellitus and hypertension, respectively. Among the participants, 39.0% GDM was not controlled based on both fasting and 2 h after breakfast glycemic levels, and 45.7% were deemed as controlled. In addition, 41.9% were overweight, and 36.2% were obese. However, neither previous pregnancy diabetes nor hypertension history, nor BMI status were significantly associated with depression, but current GDM glycemic status was. In fact, the lesser the GDM control, the more likely subjects were to report depression (f = 22.40, p < 0.001) (Tables 3, 4).

Discussion

The prevalence of severe levels of depressive symptoms among women with GDM was 36.2% and was associated with a history of abortion, neonatal death, and poor GDM glycemic control. This study shows that the presence of GDM, particularly when glycemia is not well-controlled among expectant Bangladeshi mothers, is associated with an increased risk of depression. It is now well established that the presence of antenatal and postpartum depression imposes substantial adverse effects on both mothers and their offspring [17, 31, 32]. In addition, many of the mothers with antenatal depression will also suffer from depression after labor and delivery, with 39% of postnatal depression rates being attributable as being initiated and established during the pregnancy period [31]. Thus, early identification and treatment of antenatally depressed subjects with GDM are critical [33, 34].

Before entertaining the potential implications of the present study, several methodological issues deserve comment. First of all, this was a cross-sectional study which may hinder the ability to infer causal associations. Second, participants were identified from four hospitals and included a relatively small sample size; therefore, generalizability may be limited. Third, this study lacked a control group of participants without GDM, a comparative control group. However, the present study provides important and scarcely available information in the Bangladeshi context, and the findings further reinforce the need to expand the study and identify viable pragmatic interventions to prevent the deleterious consequences of GDM and depression on both mother and child.

The prevalence of all severities of depression was 36.2%, whereas the only prior study assessing depression in Bangladesh reported a prevalence of 18.32% among pregnant women with and without GDM [23]. Furthermore, the investigators reported that a prevalence of 25.92% (12.70%, 5.48% and 0.14% mild, moderate and severe depression, respectively) for antenatal depression was present among women with GDM [23]. Of note, a review article estimated the prevalence of mental disorders in Bangladesh within 6.5 to 31.0% of all adult subjects [35], while the median prevalence of antenatal depression has been estimated to be around 14.7–24.3% globally [17, 31, 36]. Furthermore, the prevalence rates of antenatal depression were 7.4%, 12.8%, and 12.0% in the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively [37]. However, antenatal depression rates as high as 57% have been reported in LMIC such as Bangladesh [3], with a pooled prevalence estimated around 34.0% (compared to 22.7% in middle-income countries) [5]. Depression-related studies considering special situations of pregnant women (for example, gestational diabetes) are somewhat limited in the literature [17, 36]; only a prior study was conducted in Bangladesh [23].

Although many factors related to socio-demographic (e.g., low socioeconomic status, low social support, lower education levels, poor marital relationships etc.), psychological (e.g., psychiatric illness history, stressful life events, exposure to violence etc.), and health (e.g., negative attitude towards pregnancy, negative obstetric history etc.) have been associated with antenatal depression risk [1, 3, 5], the potential contribution of GDM to this risk has only been sporadically examined. However, as suggested by the present study, pregnant women with GDM are at high risk of depression, and such risk is further exacerbated by poor control of their glycemic state.

GDM subjects with a history of reproductive health-related complexities were more likely to be depressed. Such associations have been previously identified, and the present study concurs with such findings [6, 7, 38]. It can be postulated that poor diabetes self-care increases the risk of depression, likely related to the complex nature of diabetes management in LMIC, and the impositions of GDM on lifestyle, particularly when the access to care is sporadic and difficult [33, 39]. Indeed, it is possible that GDM women who have ready access to interventions and medical care for their diabetes (i.e., dietary advice, glucose monitoring, insulin therapy etc.) may be less likely to develop adverse mental health outcomes [40]. Consequently, the inability to establish GDM glycemic control may simply reflect the lack of access to overall care, which may exacerbate the propensity for antenatal depression in these cases.

Conclusions

In a group of GDM women, 36.2% suffered from depressive symptoms, and the depression severity was enhanced by the presence of underlying poor glycemic control. Considering the known negative impact of GDM and depression on pregnancy-related outcomes, early screening of these conditions should be pursued, preferentially once every trimester over the duration of the gestational period.

Acknowledgements

The present study was carried out as part of the fulfillment of MPH thesis at the National Institute of Preventive and Social Medicine, Bangladesh. In addition, it should be noted that the CHINTA Research Bangladesh was formerly known as the Undergraduate Research Organization.

Abbreviations

- ABF

2H after breakfast

- BG

Blood glucose

- BMI

Body mass index

- GDM

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- LMICs

Low-and middle-income countries

- MADRS

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale

Authors’ contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study did not get any financial support.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

A formal ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the National Institute of Preventive and Social Medicine, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Participants had to provide consent by signature or thumb impression.

Consent for publication

All participants consented for publication of their information.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord, Elsevier. 2016;191:62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Maternal and Child Mental Health [Internet]. 2021 [cited 3 Apr 2021]. Available: https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/en/.

- 3.Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Araya R, Williams MA. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry, Elsevier. 2016;3:973–982. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30284-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord, Elsevier. 2017;219:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dadi AF, Miller ER, Mwanri L. Antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, Public Library of Science. 2020;15:0227323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannandrea SAM, Cerulli C, Anson E, Chaudron LH. Increased risk for postpartum psychiatric disorders among women with past pregnancy loss. J Women’s Heal, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 2013;22:760–768. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broen AN, Moum T, Bødtker AS, Ekeberg O. The course of mental health after miscarriage and induced abortion: a longitudinal, five-year follow-up study. BMC Med. 2005;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasheduzzaman M, Al Mamun F, Faruk MO, Hosen I, Mamun MA. Depression in Bangladeshi university students: the role of sociodemographic, personal, and familial psychopathological factors. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021 doi: 10.1111/ppc.12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Diabetes - WHO [Internet]. 2020 [cited 3 Apr 2021]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes.

- 11.Veeraswamy S, Vijayam B, Gupta VK, Kapur A. Gestational diabetes: the public health relevance and approach. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, Elsevier. 2012;97:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas-7th edition [Internet]. 2015 [cited 3 Apr 2021]. Available: https://diabetesatlas.org/upload/resources/previous/files/7/IDF Diabetes Atlas 7th.pdf. [PubMed]

- 13.Lee KW, Ching SM, Ramachandran V, Yee A, Hoo FK, Chia YC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Preg Childbirth, BioMed Central. 2018;18:494. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2131-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayeed MA, Mahtab H, Khanam PA, Begum R, Banu A, Azad Khan AK. Diabetes and hypertension in pregnancy in a rural community of Bangladesh: a population-based study. Diabet Med, Wiley Online Library. 2005;22:1267–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jesmin S, Akter S, Akashi H, Al-Mamun A, Rahman MA, Islam MM, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus and its prevalence in Bangladesh. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, Elsevier. 2014;103:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mustafa FN. Pregnancy profile and perinatal outcome in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: a hospital based study. J Bangladesh Coll Physicians Surg, Bangladesh Academy of Sciences. 2015;33:79–85. doi: 10.3329/jbcps.v33i2.28040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross GP, Falhammar H, Chen R, Barraclough H, Kleivenes O, Gallen I. Relationship between depression and diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review. World J Diabetes, Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. 2016;7:554–571. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v7.i19.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrn MA, Penckofer S. Antenatal depression and gestational diabetes: a review of Maternaland fetal outcomes. Nurs Womens Health, Elsevier. 2013;17:22–33. doi: 10.1111/1751-486X.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damé P, Cherubini K, Goveia P, Pena G, Galliano L, Façanha C, et al. Depressive symptoms in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: the LINDA-Brazil Study. J Diabetes Res, Hindawi. 2017;2017:7341893. doi: 10.1155/2017/7341893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KW, Ching SM, Hoo FK, Ramachandran V, Chong SC, Tusimin M, et al. Neonatal outcomes and its association among gestational diabetes mellitus with and without depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. Midwifery, Elsevier. 2020;81:102586. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.102586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muche AA, Olayemi OO, Gete YK. Gestational diabetes mellitus increased the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes: a prospective cohort study in Northwest Ethiopia. Midwifery, Elsevier. 2020;87:102713. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Persson M, Shah PS, Rusconi F, Reichman B, Modi N, Kusuda S, et al. Association of maternal diabetes with neonatal outcomes of very preterm and very low-birth-weight infants: an international cohort study. JAMA Pediatr, American Medical Association. 2018;172:867–875. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natasha K, Hussain A, Khan AKA. Prevalence of depression among subjects with and without gestational diabetes mellitus in Bangladesh: a hospital based study. J Diabetes Metab Disord, Springer. 2015;14:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0189-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rospleszcz S, Schafnitzel A, Koenig W, Lorbeer R, Auweter S, Huth C, et al. Association of glycemic status and segmental left ventricular wall thickness in subjects without prior cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, BioMed Central. 2018;18:162. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0900-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Diabetes Association Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care, American Diabetes Association. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S88–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Adult BMI [Internet]. 2020 [cited 8 Mar 2021]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html.

- 27.Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry, Cambridge University Press. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhowmik B, Munir SB, Hossain IA, Siddiquee T, Diep LM, Mahmood S, et al. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose regulation with associated cardiometabolic risk factors and depression in an urbanizing rural community in Bangladesh: a population-based cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab J, Korean Diabetes Association. 2012;36:422–432. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.6.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soron TR. Validation of Bangla Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRSB) Asian J Psychiatr, Elsevier. 2017;28:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zahid N, Asghar S, Claussen B, Hussain A. Depression and diabetes in a rural community in Pakistan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, Elsevier. 2008;79:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Underwood L, Waldie K, D’Souza S, Peterson ER, Morton S. A review of longitudinal studies on antenatal and postnatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health, Springer. 2016;19:711–720. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0629-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DelRosario GA, Chang AC, Lee ED. Postpartum depression: symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment approaches. J Am Acad Physician Assist, LWW. 2013;26:50–54. doi: 10.1097/01720610-201302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotella F, Mannucci E. Depression as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Clin Psychiatry, Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. 2013;74:31–37. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord, Elsevier. 2012;142:S8–S21. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(12)70004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hossain MD, Ahmed HU, Chowdhury WA, Niessen LW, Alam DS. Mental disorders in Bangladesh: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, BioMed Central. 2014;14:216. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahendran R, Puthussery S, Amalan M. Prevalence of antenatal depression in South Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Commun Health, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. 2019;73:768–777. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol, LWW. 2004;103:698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt CB, Voorhorst I, VandeGaar VHW, Keukens A, PottervanLoon BJ, Snoek FJ, et al. Diabetes distress is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with gestational diabetes: a prospective cohort study. BMC Preg Childbirth, BioMed Central. 2019;19:223. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care, American Diabetes Association. 2008;31:2398–2403. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med, Massachusetts Medical Society. 2005;352:2477–2486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.