Abstract

Introduction

Hydrocephalus is a chronic medical condition that has a significant impact on children and their caregivers. The objective of this study was to measure quality of life (QOL) of children with hydrocephalus, as assessed by both caregivers and patients.

Methods

Pediatric patients with hydrocephalus and their caregivers were enrolled during routine neurosurgery clinic visits. The Hydrocephalus Outcomes Questionnaire (HOQ), a report of hydrocephalus-related quality of life, was administered to both children with hydrocephalus (self-report) and their caregivers (proxy-report about the child). Patients with hydrocephalus also completed measures of anxiety, depression, fatigue, traumatic stress, and headache. Caregivers completed a proxy-report of child traumatic stress and a measure of caregiver burden. Demographic information was collected from administration of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT 2.0) and from the medical record. Child and caregiver HOQ scores were analyzed and correlated with clinical, demographic, and psychological variables.

Results

The mean overall HOQ score (parent assessment of child QOL) was 0.68. HOQ Physical Health, Social-Emotional Health, and Cognitive Health subscore averages were 0.69, 0.73, 0.54, respectively. Mean overall child self-assessment (cHOQ) score was 0.77, with cHOQ Physical Health, Social-Emotional Health, and Cognitive Health subscore means of 0.84, 0.79, 0.66, respectively. We analyzed 39 dyads, in which both a child with hydrocephalus and his or her caregiver completed the cHOQ and HOQ. There was a positive correlation between parent and child scores (p<0.004 for all subscores). Child scores were consistently higher than parent scores. Variables that showed association with caregiver-assessed QOL in at least one domain included child age, etiology of hydrocephalus and history of ETV. There was a significant negative relationship (rho −0.42 to −0.59) between child-reported cHOQ score and child-reported measures of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and fatigue. There was a similar significant relationship between caregiver report of child’s quality of life (HOQ) and caregiver assessment of the child’s post-traumatic stress symptoms as well as their assessment of burden of care (rho=−0.59 and rho=−0.51, respectively). No relationship between parent-reported HOQ and child-reported psychosocial factors was significant. No clinical or demographic variables were associated with child self-assessed cHOQ.

Conclusions

Pediatric patients with hydrocephalus consistently rate their own quality of life higher than their caregivers do. Psychological factors such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress may be associated with lower quality of life. These findings warrant further exploration.

Keywords: hydrocephalus, quality of life, pediatrics, caregivers

Introduction

Hydrocephalus is a life-altering, chronic condition that has a significant impact on children and their caregivers. It is recognized that quality-of-life (QOL) can be negatively affected in pediatric hydrocephalus patients and their families. Previous studies have demonstrated that children with hydrocephalus have lower QOL scores than children without hydrocephalus, as assessed by their caregivers1. Lower QOL has been associated with socioeconomic factors, such as family income and parental education, as well as disease-related factors, like presence of epilepsy or etiology of hydrocephalus2.

Almost all studies of quality of life in children with hydrocephalus have used surveys completed by the parent or caregiver. To our knowledge, only one study has assessed child self-reported QOL3. In this study, Kulkarni et al. reported a correlation between child and parent report of QOL.

The primary objective of this study was to measure the health related QOL of children with hydrocephalus, as assessed by both caregivers and pediatric patients themselves. The secondary objective was to directly compare QOL assessment between caregiver-child dyad pairs. In addition, we sought to determine what factors were associated with lower QOL for these children and their caregivers, assessing factors previously established in the existing literature, as well as conducting the first study of psychological comorbidities and their association with QOL. We hypothesize that factors such as anxiety, depression, fatigue, severity of headache, and presence of post-traumatic stress symptoms will negatively correlate with quality of life.

Methods

Setting

Study enrollment took place over a seven-month period in 2017–2018. Participants were recruited during their annual neurosurgical clinic visit at Children’s of Alabama (COA), a tertiary referral center for pediatric neurosurgery in the southeastern United States.

Study Population

Caregivers of pediatric patients with hydrocephalus and pediatric patients themselves were eligible for enrollment. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were between five and twenty-one years of age and were capable of independently completing the survey as assessed by caregiver and research staff. Recognizing that some children with hydrocephalus have cognitive difficulties, research staff along with the caregiver determined if a child was capable of independently completing the questionnaire. This determination involved an assessment of level of consciousness, ability to read or to understand questions read aloud, ability to respond to the questions either verbally or in writing, and maturity level. Patients were eligible for enrollment regardless of whether their caregiver chose to enroll in the study.

Caregivers were eligible for enrollment if they were the legal guardian of a child with hydrocephalus between five and twenty-one years of age. In the event that the caregiver’s child was not eligible for enrollment due to inability to independently complete research survey or refusal to participate, the caregiver was still eligible for enrollment. If more than one caregiver was present at their child’s clinic visit, both caregivers were eligible for enrollment, however, during the course of the study, in every case, only one caregiver was present or willing to participate. Therefore, study results represent the responses of the caregiver who is the primary caregiver in the context of the child’s neurosurgical clinic visit.

Because caregiver and patient enrollment were not mutually exclusive, there were three different study populations 1.) caregivers of children with hydrocephalus, 2.) children with hydrocephalus, 3.) caregiver-child pairs (“dyads”) who both enrolled in the study.

Only English-speaking participants were eligible, given the lack of availability of the study instruments in other languages. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Alabama at Birmingham4.

Data Collection

Prior to enrollment, ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. A research assistant, trained in both informed consent and research ethics, obtained consent from study participants during their routine pediatric neurosurgery clinic visit. Both parent/caregiver and child study participants completed the Hydrocephalus Outcome Questionnaire (HOQ), a 51-question instrument to measure the health status in children living with hydrocephalus5. The HOQ is a validated instrument for measuring quality of life in children with hydrocephalus. The HOQ measures overall quality of life and provides subscores to assess three domains: Social-Emotional Health, Cognitive Health, and Physical Health. The HOQ is primarily used as a parental proxy evaluation, with the parent or caregiver performing the assessment of their child. For children with hydrocephalus, the cHOQ is a self-report version of the HOQ, including the same 51 items, scored in the same way3. The HOQ is scored on a scale of 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating higher QOL. The HOQ has previously been used in caregivers of patients ages 5 years of age and older, and the cHOQ has been used in pediatric patients with hydrocephalus ages 6–193,5.

Demographic social variables were collected from the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT 2.0), a validated parent report screen of psychosocial risk in pediatric health and are summarized in Table 16. Distance of the child’s residence to Children’s of Alabama hospital was calculated from the patient’s most recent zip code, as obtained from the patient’s electronic medical record. Clinical variables such as etiology of hydrocephalus, number of hydrocephalus-related procedures, and history of shunt infection were collected from institutional records. All of these data points are collected prospectively as part of institutional participation in the Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network (HCRN) registry. Additionally, the electronic medical record was utilized to collect information such as child’s gestational age at birth, total number of non-temporary hydrocephalus procedures, and total number of external ventricular drain placements. Recognizing that shunts can fail repeatedly, and that this may increase the risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), we defined a new variable to capture those patients who had a history of a cluster of shunt revisions. The variable, shunt cluster, was defined as having three or more hydrocephalus operations within a 2-month period.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Variables

| Variable | Caregiver Participant Characteristics (n=91) | Child Participant Characteristics (n=39) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age of Child, years | (n=83) | (n=39) |

| Mean | 11.41 | 14.03 |

| SD | 5.02 | 4.50 |

|

| ||

| Child Gender | ||

| Female | 37 (41%) | 19 (49%) |

| Male | 46 (51%) | 20 (51%) |

|

| ||

| Child Race | ||

| White | 55 (60%) | 27 (69%) |

| Non-White | 28 (31%) | 12 (31%) |

|

| ||

| Etiology of Hydrocephalus | ||

| Aqueductal stenosis | 4 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Intra-ventricular hemorrhage | 22 (24%) | 7 (18%) |

| Myelomeningocele | 17 (19%) | 6 (15%) |

| Post infectious | 7 (8%) | 3 (8%) |

| Spontaneous hemorrhage | 1 (1%) | 1 (3%) |

| Midbrain tumor or lesion | 3 (3%) | 3 (8%) |

| Post-head injury | 4 (4%) | 2 (5%) |

| Posterior fossa cyst | 1 (1%) | 2 (5%) |

| Other intracranial cyst | 1 (1%) | 1 (3%) |

| Communicating congenital | 12 (13%) | 8 (21%) |

| Other congenital | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 2 (2%) | 2 (5%) |

|

| ||

| ETV Alone (no shunt in lifetime) | ||

| No | 70 (77%) | 30 (77%) |

| Yes | 7 (8%) | 4 (10%) |

|

| ||

| History of Shunt Infection | ||

| No | 57 (63%) | 27 (69%) |

| Yes | 21 (23%) | 8 (21%) |

|

| ||

| History of clustered shunt failure | ||

| No clusters | 64 (70%) | 26 (67%) |

| Clusters | 12 (13%) | 7 (18%) |

|

| ||

| Total Number of EVDs | ||

| None | 48 (53%) | 22 (56%) |

| 1 or more | 29 (32%) | 12 (31%) |

|

| ||

| Gestational Age at Birth, weeks | (n=74) | (n=31) |

| Mean | 34.18 | 35.19 |

| SD | 5.98 | 5.68 |

|

| ||

| Number of Hydrocephalus Procedures | (n=78) | (n=35) |

| Mean | 4.28 | 4.54 |

| SD | 5.06 | 6.54 |

|

| ||

| Type of Health Insurance | ||

| Other | 43 (47%) | 19 (49%) |

| Private | 36 (40%) | 17 (44%) |

|

| ||

| Age of Caregiver | ||

| Age 21 or over | 73 (80%) | 32 (82%) |

| Other | 8 (9%) | 5 (13%) |

|

| ||

| Caregiver Education | ||

| College/Graduate Education | 42 (46%) | 18 (46%) |

| Other | 39 (43%) | 19 (49%) |

| Caregiver Marital Status | ||

| Married/partnered | 57 (63%) | 22 (56%) |

| Other | 24 (26%) | 15 (38%) |

|

| ||

| Distance from hospital, miles | (n=77) | (n=34) |

| Mean | 87.76 | 91.44 |

| SD | 57.55 | 49.31 |

|

| ||

| Time from last surgery, months | (n=82) | (n=39) |

| Mean | 67.66 | 76.16 |

| SD | 58.78 | 71.58 |

|

| ||

| Child with developmental problems | ||

| Yes or getting help | 22 (24%) | 9 (23%) |

| Sometimes | 19 (21%) | 9 (23%) |

| No | 28 (31%) | 16 (41%) |

EVD: external ventricular drain, ETV: endoscopic third ventriculostomy, SD: standard deviation

Average survey completion time was thirty minutes. No specific precautions were taken to avoid survey fatigue. Participants were not compensated for study participation. If subjects did not complete all survey measures, only completed surveys were included in data analysis.

Psychological Variables

To measure psychological variables, we used several validated survey instruments. To assess PTSS, we administered the Child Stress Disorders Checklist (CSDC), a parent report of child post-traumatic stress in children ages 2–187. In addition to this parent-report of PTSS, we administered the Acute Stress Checklist for Kids (ASC-Kids), a child self-report measure for children ages 8–178. Pediatric patients completed three PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) measures of psychological comorbidities in children ages 8–17: PROMIS Anxiety, PROMIS Depression, and PROMIS Fatigue scales9. To measure the burden of headache, pediatric patients completed the Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment (PedMIDAS), an assessment of migraine disability in patients ages 4–1810. Finally, caregivers completed the Zarit Burden Interview, an assessment of caregiver perception of the burden of providing care for a loved one with a chronic illness and its impact on health, personal, and social well-being11.

Statistical Analysis

Three study group were analyzed: 1.) caregivers of patients with hydrocephalus, 2.) patients with hydrocephalus, and 3.) caregiver-patient pairs (“dyads”) who both enrolled in the study.

Demographic characteristics that are categorical were summarized using counts and percentages, while continuous demographic and outcome variables were summarized using means and standard deviations. Kruskall-Wallis test was used to compare the continuous QOL and psychological scores for different categories of a categorical variables that had small numbers in some categories (for example, age of caregivers, etiology of hydrocephalus, and ETV-alone hydrocephalus treatment. In these cases, we prefer to use non-parametric tests as tests for normality may not perform as well as needed with small numbers. For uniformity, we used Kruskall-Wallis for all other categorical variables as well. Scatterplots were examined, and Pearson correlation was estimated and tested (null hypothesis: correlation=0) to examine the association among pairs of continuous variables. Parametric tests were used for these comparisons because the issue of small numbers noted above was not a concern. For the dyads, we calculated the differences in responses between the matched parent and child. We presented the mean and standard deviation of these differences. To determine if the parent responses differ significantly from the child, we used signed rank test. Due to multiple tests performed, we used Bonferroni method by dividing 0.05 by the total number of tests. Because this method is very conservative and this study is exploratory in nature, we made adjustments separately for parent and child analyses. In investigating which demographic and clinical characteristics are significantly associated with HOQ scores, the total number of variables used was 17 (listed in Table 1) hence a cutoff for determining significance of 0.0029. For comparing HOQ with 7 psychological variables, we use the cut-off of 0.0071 (=0.05/7). In all the tables, raw unadjusted p-values were presented. All analyses were done using SAS version 9.4.

Missing Data

Missing clinical and demographic data are due to the following: caregiver did not complete Psychosocial Assessment Tool, pediatric patient not enrolled in the Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network Registry, and information not available in the electronic medical record. Only those with available data were included in a given analyses.

Results

Ninety-one caregivers and 39 children with hydrocephalus were enrolled in this study (Figure 1). Among these cohorts, there were 39 dyad-pairs, in which both a child with hydrocephalus and their caregiver completed the HOQ and cHOQ. Detailed information on the sample of both caregivers and children can be found in Table 1.

Figure 1:

Enrollment Diagram

The mean overall HOQ score (parent assessment of child QOL) was 0.68. HOQ Physical Health, Social-Emotional Health, and Cognitive Health subscore averages were 0.69, 0.73, 0.54, respectively. Mean overall child self-assessment (cHOQ) score was 0.77, with cHOQ Physical Health, Social-Emotional Health, and Cognitive Health subscore means of 0.84, 0.79, 0.66, respectively. We analyzed 39 dyads, in which both a child with hydrocephalus and his or her caregiver completed the cHOQ and HOQ, respectively. As expected, linear regression shows a positive correlation between parent and child scores (p<0.004 for all subscores). Physical health showed the strongest correlation between parent and child scores (rho=0.77). However, child scores were consistently higher than parent scores. This difference was statistically significant for physical QOL (Table 2).

Table 2.

Caregiver and Child HOQ Scores and Dyad Scores

| HOQ Score | Caregiver Assessment (n=91) Mean±SD |

Caregiver Assessment (n=39) Mean±SD |

Child Self-Report (n=39) Mean±SD |

Dyad Difference (Child Score-Caregiver Score) Mean±SD |

Dyad Difference P-value |

Dyad Pearson Correlation | Dyad Pearson Correlation P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Health | 0.68± 0.17 | 0.74± 0.14 | 0.77± 0.13 | 0.04± 0.13 | 0.096 | 0.52 | 0.0007 |

| Physical Health | 0.69± 0.21 | 0.80± 0.14 | 0.84± 0.14 | 0.05± 0.09 | 0.0035 | 0.77 | <0.0001 |

| Social-Emotional Health | 0.73± 0.17 | 0.76± 0.16 | 0.79± 0.14 | 0.03± 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.005 |

| Cognitive Health | 0.54± 0.28 | 0.62± 0.27 | 0.66± 0.23 | 0.04± 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.0006 |

Variables that showed association with caregiver assessment of at least one domain of quality of life prior to applying the Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05) were child age, child gender, etiology of hydrocephalus, number of procedures, history of ETV alone (no ventriculoperitoneal [VP] shunt), and history of shunt infection (Table 3). After applying the Bonferroni correction, only child age (older age associated with higher physical QOL score), etiology of hydrocephalus (aqueductal stenosis associated with higher overall and physical QOL than other etiologies), and history of ETV (ETV without VP shunt associated with higher overall QOL) maintained significance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Caregiver-report HOQ Correlation with Clinical and Demographic Factors

| Variable | Overall Health | Cognitive Health | Physical Health | Social-Emotional Health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Mean (SD) or rho | P-Value | Mean (SD) or rho | P-Value | Mean (SD) or rho | P-Value | Mean (SD) or rho | P-Value | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Child age | Rho= 0.24 | 0.02 | rho=0.32 | 0.002* | 0.095 | 0.38 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Child gender | Male | 0.72 (0.16) | 0.008 | 0.60 (0.26) | 0.02 | 0.75 (0.18) | 0.02 | 0.76 (0.17) | 0.05 |

| Female | 0.62 (0.17) | 0.47 (0.29) | 0.63 (0.23) | 0.69 (0.17) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Etiology | Myelomeningocele (MMC) | 0.62 (0.18) | 0.02 | 0.51 (0.25) | 0.03 | 0.57 (0.18) | 0.0002* | 0.72 (0.20) | 0.67 |

| Hemorrhage (IVH) | 0.60 (0.20) | 0.40 (0.28) | 0.60 (0.25) | 0.71 (0.19) | |||||

| Aqueductal stenosis (AS) | 0.78 (0.16) | 0.68 (0.30) | 0.80 (0.15) | 0.83 (0.13) | |||||

| Other | 0.72 (0.14) | 0.62 (0.27) | 0.78 (0.18) | 0.74 (0.17) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Number of procedures | Rho=−0.30 | 0.021 | rho=−0.23 | 0.04 | −0.17 | 0.12 | rho=−0.30 | 0.007 | |

|

| |||||||||

| ETV Alone | Yes | 0.85 (0.07) | 0.002* | 0.82 (0.16) | 0.02 | 0.86 (0.10) | 0.86 (0.08) | 0.044 | |

| No | 0.66 (0.17) | 0.52 (0.28) | 0.68 (0.22) | 0.02 | 0.72 (0.18) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Shunt Infection | Yes | 0.63 (0.16) | 0.13 | 0.57 (0.29) | 0.21 | 0.60 (0.24) | 0.021 | 0.72 (0.17) | 0.57 |

| No | 0.70 (0.18) | 0.48 (0.27) | 0.73 (0.20) | 0.74 (0.18) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age of Main Caregiver | Age 21 or over | 0.67 (0.17) | 0.30 | 0.54 (0.28) | 0.44 | 0.69 (0.21) | 0.58 | 0.73 (0.18) | 0.86 |

| Other | 0.73 (0.18) | 0.62 (0.27) | 0.79 (0.25) | 0.75 (0.15) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Child Race | White | 0.68 | 0.18 | 0.56 (0.29) | 0.33 | 0.69 (0.23) | 0.78 | 0.73 (0.18) | 0.86 |

| Non-white | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.51 (0.26) | 0.72 (0.19) | 0.74 (0.16) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Caregiver Education | College/grad | 0.69 (0.16) | 0.90 | 0.55 (0.26) | 0.93 | 0.69 (0.22) | 0.71 | 0.75 (0.16) | 0.42 |

| Other | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.55 (0.29) | 0.71 (0.21) | 0.72 (0.19) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Marital Status | Married/partnered | 0.67 (0.17) | 0.23 | 0.54 (0.28) | 0.74 | 0.68 (0.21) | 0.13 | 0.72 (0.18) | 0.32 |

| Other | 0.71 (0.17) | 0.56 (0.28) | 0.74 (0.20) | 0.76 (0.16) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Type of health insurance | Other | 0.67 (0.16) | 0.61 | 0.52 (0.26) | 0.15 | 0.71 (0.19) | 0.94 | 0.73 (0.18) | 0.82 |

| Private | 0.70 (0.18) | 0.60 (0.29) | 0.70 (0.22) |

0.74 (0.17) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Number of clusters | None | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.45 | 0.54 (0.28) | 0.66 | 0.71 (0.22) | 0.14 | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.21 |

| 1 or more | 0.64 (0.17) | 0.58 (0.29) | 0.64 (0.20) | 0.67 (0.21) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total number of EVDs | None | 0.70 (0.17) | 0.18 | 0.57 (0.28) | 0.31 | 0.73 (0.20) | 0.03 | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.58 |

| 1 or more | 0.64 (0.18) | 0.50 (0.28) | 0.63 (0.23) | 0.72 (0.18) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Gestational age at birth | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.14 | −0.003 | 0.98 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Distance from hospital | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.54 | |

Bold print in p-values indicates a statistically significant association after correction for multiple measures (p<0.0029).

As shown in Table 4, when considering child self-reported QOL, fewer variables showed significant association prior to application of correction for multiple measures (p<0.05). Increasing number of hydrocephalus procedures was associated with lower overall (rho = −0.34, p=0.03) and cognitive QOL scores (rho = −0.30, p=0.008). Children whose parents had college or graduate school education had lower cognitive QOL than children of parents with lower levels of education (0.60 vs 0.75, p=0.041). However, none of these associations maintained significance (p<0.0029) after Bonferroni correction.

Table 4.

Child-report HOQ Correlation with Clinical and Demographic Factors

| Variable | Overall Health | Cognitive Health | Physical Health | Social-Emotional Health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Mean (SD) or regression coefficient | P-Value | Mean (SD) or regression coefficient | P-Value | Mean (SD) or regression coefficient | P-Value | Mean (SD) or regression coefficient | P-Value | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Number of Procedures | rho=−0.34 | 0.03 | rho=−0.30 | 0.008 | −0.22 | 0.18 | −0.26 | 0.10 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Caregiver Education | College/Grad | 0.76 (0.12) | 0.60 (0.23) | 0.041 | 0.84 (0.12) | 0.36 | 0.78 (0.12) | 0.43 | |

| Other | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.75 (0.19) | 0.87 (0.14) | 0.80 (0.15) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age of Main Caregiver | Age 21 or over | 0.78 (0.13) | 0.84 | 0.68 (0.22) | 0.84 | 0.85 (0.13) | 0.21 | 0.79 (0.14) | 0.96 |

| Other | 0.80 (0.12) | 0.67 (0.23) | 0.90 (0.12) | 0.81 (0.12) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Child Gender | Male | 0.83 (0.12) | 0.05 | 0.72 (0.21) | 0.18 | 0.88 (0.12) | 0.18 | 0.84 (0.11) | 0.06 |

| Female | 0.75 (0.12) | 0.63 (0.24) | 0.84 (0.14) | 0.75 (0.14) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Child Race | White | 0.80 (0.14) | 0.33 | 0.70 (0.24) | 0.29 | 0.87 (0.13) | 0.36 | 0.81 (0.14) | 0.43 |

| Non-white | 0.77 (0.10) | 0.64 (0.22) | 0.84 (0.13) | 0.78 (0.13) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Marital Status | Married/Partnered | 0.77 (0.13) | 0.61 | 0.67 (0.23) | 0.92 | 0.85 (0.14) | 0.77 | 0.78 (0.13) | 0.37 |

| Other | 0.80 (0.12) | 0.69 (0.22) | 0.86 (0.12) | 0.81 (0.14) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Type of Health Insurance | Other | 0.77 (0.13) | 0.32 | 0.66 (0.22) | 0.44 | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.05 | 0.78 (0.14) | 0.91 |

| Private | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.71 (0.24) | 0.90 (0.09) | 0.80 (0.12) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ETV Alone | No | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.32 | 0.69 (0.24) | 0.75 | 0.88 (0.12) | 0.11 | 0.80 (0.14) | 0.56 |

| Yes | 0.73 (0.15) | 0.63 (0.22) | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.78 (0.14) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Etiology of Hydrocephalus | Myelomeningocele ((MMC) | 0.73 (0.10) | 0.12 | 0.61 (0.19) | 0.25 | 0.82 (0.09) | 0.09 | 0.72 (0.14) | 0.11 |

| Hemorrhage (IVH) | 0.78 (0.17) | 0.70 (0.25) | 0.83 (0.19) | 0.78 (0.18) | |||||

| Aqueductal stenosis (AS) | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Other | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.69 (0.25) | 0.89 (0.11) | 0.93 (0.10) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Number of Clusters | None | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.20 | 0.71 (0.23) | 0.23 | 0.89 (0.11) | 0.08 | 0.81 (0.13) | 0.42 |

| 1 or more | 0.73 (0.15) | 0.61 (0.23) | 0.79 (0.18) | 0.75 (0.16) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| History of Shunt Infection | Yes | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.18 | 0.59 (0.25) | 0.23 | 0.87 (0.14) | 0.27 | 0.75 (0.15) | 0.37 |

| No | 0.74 (0.10) | 0.70 (0.23) | 0.85 (0.10) | 0.81 (0.13) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total Number of EVDs | None | 0.79 (0.13) | 0.81 | 0.68 (0.23) | 0.93 | 0.87 (0.14) | 0.85 | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.78 |

| 1 or more | 0.79 (0.14) | 0.67 (0.26) | 0.86 (0.12) | 0.80 (0.16) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Gestational Age at Birth | −0.11 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.89 | −0.07 | 0.68 | −0.20 | 0.25 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Child Age | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.83 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Distance from Hospital (miles) | −0.06 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.83 | −0.28 | 0.08 | 0.012 | 0.91 | |

Association of QOL with Psychological Comorbidities

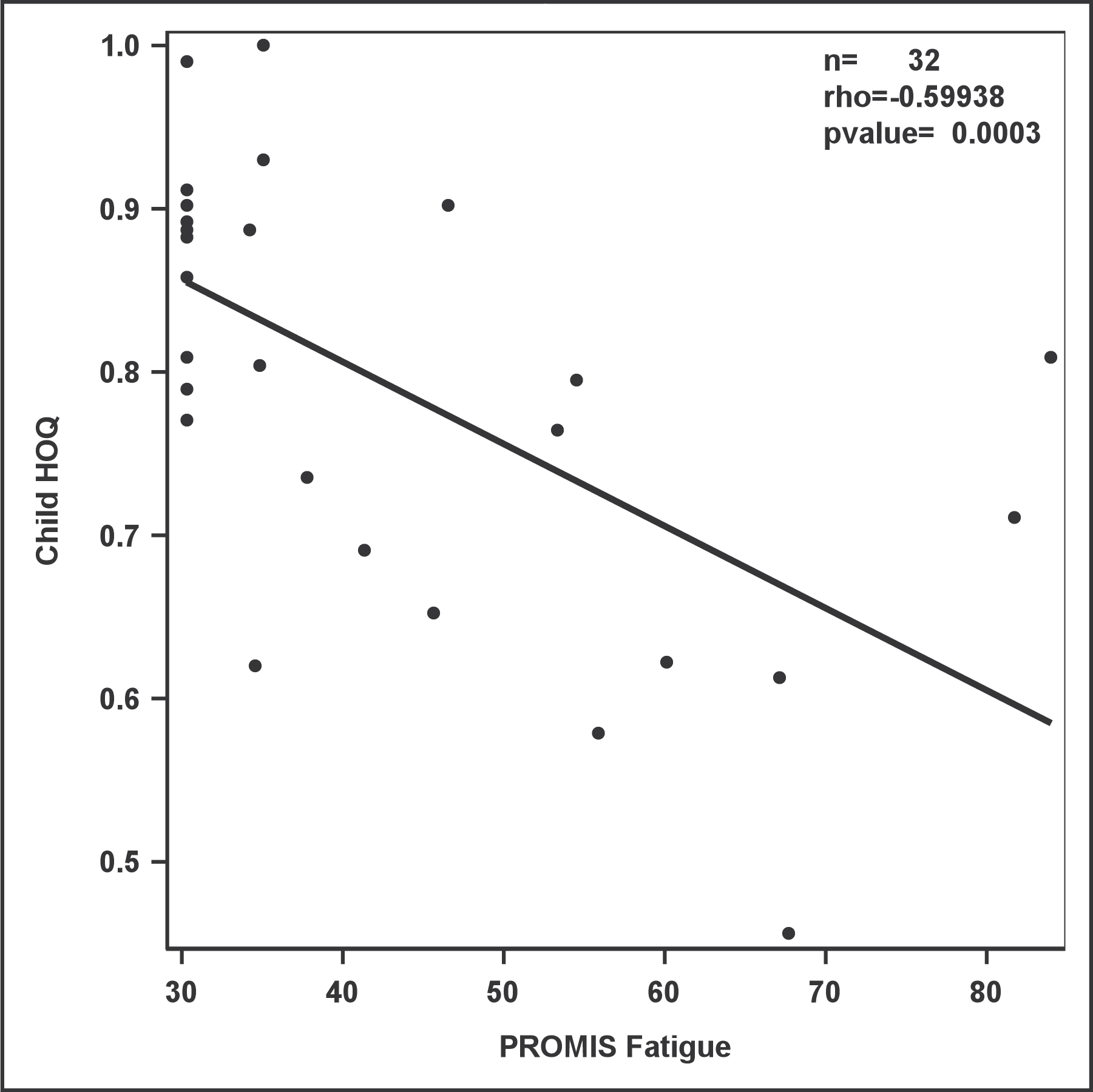

When comparing overall QOL with components of the psychological assessment, several statistically significant associations were apparent. There was a negative relationship (rho −0.42 to −0.59) between child-reported cHOQ score and most other child-report measures (ASC-Kids, PROMIS Anxiety, Depression, and Fatigue scores). The exception was headache-related disability (PedMIDAS), which only approached statistical significance. Children who rated themselves higher on these scales also rated their overall QOL lower. However, there was not a significant association between parent-reported psychosocial assessments and child-reported cHOQ (Table 5). Similarly, we observed a significant relationship between the parent’s report of the child’s QOL (HOQ) and parent assessment of the child’s post-traumatic stress symptoms (CSDC) as well as their assessment of burden of care (rho=−0.59 and rho=−0.51, respectively). Here again, higher perceived burden of care and more severe PTSS were associated with lower overall QOL. No significant relationship between parent-reported QOL and child-reported psychosocial factors was seen. Correlations can be seen in Figures 2–4.

Table 5.

HOQ Correlation with Psychological Factors

| Survey | Child-Reported Quality of Life | Parent-Reported Quality of Life | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear regression coefficient (Rho) | p-value | Linear regression coefficient (Rho) | p-value | |

| Child-reported Measures | ||||

| Acute Stress Checklist for Kids (ASC-Kids) | −0.50 | 0.0016 | 0.04 | 0.85 |

| PedMIDAS Headache Tool | −0.42 | 0.0076 | −0.37 | 0.053 |

| PROMIS Anxiety | −0.55 | 0.0001 | −0.12 | 0.52 |

| PROMIS Depression | −0.42 | 0.0043 | 0.06 | 0.76 |

| PROMIS Fatigue | −0.59 | <0.0001 | −0.25 | 0.18 |

| Parent-reported Measures | ||||

| Zarit Burden Interview | −0.39 | 0.018 | −0.51 | <0.0001 |

| Child Stress Disorders Checklist (CSDC) | −0.160 | 0.36 | −0.59 | <0.0001 |

Bold print in p-values indicates a statistically significant association after correction for multiple measures (p<0.007).

Figure 2:

Correlation of HOQ with PedMIDAS: 2a. Child HOQ, 2b. Parent HOQ

Figure 4:

Correlation of HOQ with PROMIS Measures

4a. Child HOQ v. PROMIS Anxiety; 4b. Parent HOQ v. PROMIS Anxiety;

4c. Child HOQ v. PROMIS Depression; 4d. Parent HOQ v. PROMIS Depression;

4e. Child HOQ v. PROMIS Fatigue; 4f. Parent HOQ v. PROMIS Fatigue

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate QOL in pediatric patients with hydrocephalus, as assessed both by the children themselves and their caregiver. In addition, we sought to verify the relationship of QOL with clinical variables from previously published studies and conduct the first examination of psychological variables with QOL. Several previous studies have shown correlation between clinical variables and quality of life2. For example, children with myelomeningocele or intraventricular hemorrhage as the etiology of their hydrocephalus have been reported to have lower HOQ scores12–14. We have found a similar relationship here, although only the physical component of QOL had a statistically significant association with hydrocephalus etiology. This may indicate that other components of these conditions (myelomeningocele and intraventricular hemorrhage of prematurity) that result in physical disability are a driving factor in lower QOL in these children.

Previous studies have suggested that children with more shunt-related complications have lower QOL scores.5,13 We have assessed this by testing the total number of lifetime shunt operations, history of shunt infection, total number of external ventricular drains, and history of a cluster of shunt malfunctions (defined as 3 or more operations within 2 months). None of these variables showed significant association with QOL in our analysis. Total number of shunt operations approached statistical significance for overall, cognitive, and social-emotional QOL, but does not meet the significance threshold when controlling for multiple measures. In addition, correlation coefficients for these associations are low (rho= −0.23 to −0.3) indicating weak correlation.

Social and economic factors that have previously been shown to correlate with QOL scores include family income, family functioning, and parental education.13 We assessed these factors using components of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool. We found no significant association with child race, type of health insurance (private or public), age of caregiver (over age 21 or under), caregiver marital status (married/partnered or single), or distance from the hospital. Caregiver education showed no relationship with parent-rated QOL but did show a possible relationship with child-related cHOQ score. This relationship appears paradoxical, with children whose parents had lower levels of education reporting higher cognitive QOL scores. However, this relationship did not maintain significance when corrected for multiple measures. Therefore, we would caution against placing much importance on this observation.

There were 39 parent-child dyads in this study, where both caregiver and child completed the HOQ and cHOQ, respectively. It is important to note that these both measure the quality of life of the child, and so a high level of correlation would be expected. Indeed, that is what we observed. Importantly, however, children rated their QOL higher than their parents, though that difference was only statistically significant for physical health scores. This may indicate that children with hydrocephalus perceive their own physical abilities differently than their parents. This is important to consider when designing studies or interventions focused on QOL. While parent QOL has been shown to be a reliable proxy, there may be enough difference to warrant specific attention on child self-report when possible3.

This is the first study to examine the relationship between quality of life and psychological comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression, fatigue, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. In contrast to clinical and demographic variables, where we observed few significant relationships, all psychological factors showed a correlation with QOL. Children who reported higher levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, depression, or fatigue all reported significantly lower overall quality of life. However, none of these self-reported psychological factors showed significant association with caregiver-reported overall QOL. On the other hand, parental assessment of their child’s post-traumatic stress symptoms and of the level of burden involved in caring for the child both correlated with parent-report of the child’s quality of life. But these two parent-report measures had no association with child-reported QOL. It would appear that when assessing psychological comorbidities in hydrocephalus, it is critical to consider who is making the report.

This study has several limitations. Approximately 50% of the eligible patients seen in the clinic during the enrollment period were not screened for enrollment due to unavailability of the research assistant. A relatively smaller proportion declined participation in the study. Enrollment of less than 50% of eligible subjects could lead to a biased sample. However, given that the majority of non-participation was due to lack of availability of the research assistant, it is unlikely that this introduces significant bias. Additionally, caregivers and research staff made assessments of whether a child was capable of completing the child-report questionnaires. Since these judgements were somewhat subjective, there is a possibility of selection bias in the child self-report cohort, as only children able to complete the survey independently were able to enroll. Children with significant impairments, developmental delay, cognitive disability and low maturity level were not eligible for enrollment, so quality of life and psychosocial comorbidities were unable to be assessed in these populations. It is also possible that children with more complicated hydrocephalus or more frequent shunt problems were in clinic more often, and thus more likely to be approached for participation in this study. This would also lead to selection bias, potentially enriching our sample for more severely affected children. The HOQ itself contains questions that have some overlap with PROMIS measures. This could artificially increase the degree of correlation observed between these measures. Nevertheless, we suggest that anxiety, depression, and fatigue are important comorbidities for which screening and treatment may improve QOL in these patients.

Conclusion

Psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, fatigue, and traumatic stress may have a significant association with quality of life for pediatric patients with hydrocephalus, though these factors have not been well-studied in this population. Child-reported QOL was significantly associated with child-reported symptoms, but not caregiver-reported psychological symptoms, so future studies should focus on child-reported symptoms whenever feasible. In contrast to many of the clinical and demographic variables that have been the focus of previous QOL studies, psychological factors may be modifiable. Further study of traumatic-stress, anxiety, depression, and fatigue are warranted. Routine assessment of these comorbidities in the clinical setting could lead to recognition of problems and referral for appropriate treatment. If quality of life is to be improved in this population, further research must include these factors when assessing overall health and well-being of pediatric hydrocephalus patients.

Figure 3:

Correlation of HOQ with ASC-Kids: 3a. Child HOQ, 3b. Parent HOQ

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH TL1 5TL1TR001418-03

Footnotes

Previous Presentations: Portions of this work were presented at the 2018 AANS/CNS Section on Pediatric Neurosurgery in Nashville, Tennessee, and the 2019 AANS Annual Meeting in San Diego, California. The format was an oral presentation.

References

- 1.Khan SA, Khan MF, Bakhshi SK, et al. Quality of Life in Individuals Surgically Treated for Congenital Hydrocephalus During Infancy: A Single-Institution Experience. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulkarni AV. Quality of life in childhood hydrocephalus: a review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26(6):737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulkarni AV, Cochrane DD, McNeely PD, Shams I. Comparing children’s and parents’ perspectives of health outcome in paediatric hydrocephalus. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(8):587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulkarni AV, Rabin D, Drake JM. An instrument to measure the health status in children with hydrocephalus: the Hydrocephalus Outcome Questionnaire. J Neurosurg. 2004;101(2 Suppl):134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pai ALH, Patiño-Fernández AM, McSherry M, et al. The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT2.0): psychometric properties of a screener for psychosocial distress in families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(1):50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxe G, Chawla N, Stoddard F, et al. Child Stress Disorders Checklist: a measure of ASD and PTSD in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(8):972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassam-Adams N The Acute Stress Checklist for Children (ASC-Kids): development of a child self-report measure. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(1):129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWalt DA, Gross HE, Gipson DS, et al. PROMIS(®) pediatric self-report scales distinguish subgroups of children within and across six common pediatric chronic health conditions. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2015;24(9):2195–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57(11):2034–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karmur BS, Kulkarni AV. Medical and socioeconomic predictors of quality of life in myelomeningocele patients with shunted hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018;34(4):741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulkarni AV, Cochrane DD, McNeely PD, Shams I. Medical, Social, and Economic Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life in Canadian Children with Hydrocephalus. J Pediatr. 2008;153(5):689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulkarni AV, Shams I. Quality of life in children with hydrocephalus: results from the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(5 Suppl):358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]