Abstract

We reported that application of ethanol with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) enhanced alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level. In the current experiment, the protective effect of treadmill running on liver injury caused by ethanol with LPS and CCl4 in mice was studied. Liver injury severity was determined by measuring ALT and AST level in the blood. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining, immunohistochemistry for caspase-3, and Western blotting for Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) were performed to indicate hepatocyte apoptosis. In addition, to understand the mechanism, 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation was studied by Western blotting. Treadmill exercise ameliorated ethanol with LPS and CCl4-mediated elevation of ALT and AST level. Treadmill exercise suppressed ethanol with LPS and CCl4-mediated elevation of the TUNEL-positive cell number and cleaved caspase-3 expression. Treadmill exercise suppressed ethanol with LPS and CCl4-mediated elevation of Bax expression and increased Bcl-2 expression suppressed by application of ethanol with LPS and CCl4. Treadmill exercise enhanced AMPK phosphorylation which was suppressed by application of ethanol with LPS and CCl4. Treadmill exercise has the effect of reducing liver damage caused by alcohol and or drug addiction.

Keywords: Ethanol, Liver, Lipopolysaccharide, Carbon tetrachloride, Treadmill exercise

INTRODUCTION

The liver is the largest organ in our body and has various roles such as metabolism, immunity, and detoxification. However, alcohol or chemicals cause liver damage (Kim et al., 2021). In the case of alcoholic liver disease, medical expenses are reported to be increased by an average of 8.4% annually, making it difficult to manage the disease. This should be paid more attention because it is closely related not only to alcoholic liver disease itself, but also to cardiovascular diseases such as cardiomyopathy. The mechanism of alcoholic liver injury involves a complex interplay of inflammation, apoptosis, and fibrosis (Shojaie et al., 2020; Sun and Kisseleva, 2015). Apoptotic cell death is a mechanism by which cells function normally by eliminating harmful or severely damaged cells (Ko et al., 2020; Shojaie et al., 2020). However, excessive hepatocyte apoptotic death rather leads to hepatic dysfunction, leading to acute liver injury (Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020).

Exercise can improve mental and physical health by positively affecting weight control, maintenance and development of the musculoskeletal system, and human metabolism. It is also recommended for all patients with chronic disease, and the American Liver Disease Research Association recommends personalized exercise interventions for patients with liver disease. Exercise training has a beneficial effect on maintaining good health including brain health (Mattson, 2012; Rayhan et al., 2020). Exercise is known to be effective in reducing the incidence of some metabolic abnormalities, such as cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and preventing various cell and tissue damage (Rayhan et al., 2020). Previously, we reported that application of ethanol with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) enhanced alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level (Kim et al., 2021).

In the current experiment, the protective effect of treadmill running against liver damage caused by ethanol with LPS and CCl4 in mice was studied. Liver injury severity was determined by measuring ALT and AST level in the blood. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining, immunohistochemistry for caspase-3, and Western blotting for Bcl- 2-associated X protein (Bax) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) were done to indicate hepatocyte apoptosis. In addition, to understand the mechanism, 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation was studied by Western blotting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and treatments

Male ICR mice were used for this experiment, and the experimental process was evaluated by the Animal Ethics Review Committee and approval number was achieved (KHSASP-20-495). The mice were grouped into control group, exercise group, ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application group, and ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application and exercise group (n=10 in each group). The mice in the ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application groups were given 0.5 mL of 50% ethanol orally and intraperitoneally injected with 1-mg/kg LPS and 0.6-mL/kg CCl4, once a day, 3 times a week for 6 weeks. The mice in the exercise groups performed treadmill running at speed of 8 m/min for 30 min a day for 6 weeks.

ALT and AST measurement in the blood

Using a disposable syringe, 1 mL of blood was collected from the jugular vein, and plasma was separated by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 min. ALT and AST level was detected by the method of Ko et al. (2020).

TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was done by a Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in the same manner of Park et al. (2020). The sections were treated with ethanol-acetic acid (2:1) solution, proteinase K (100 mg/mL), 3% H2O2, 0.5% Triton X-100, and finally with the TUNEL reaction mixture. After rinsing, the sections were incubated with converter-peroxidase with 0.03% diaminobenzidine, and stained with Nissl solution. After mounting the sections on gelatin-coated slides, and the slides were air-dried overnight at room temperature. Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was used for coverslips.

Caspase-3 immunohistochemistry

Caspase-3 immunohistochemistry was done in the same manner of Lee et al. (2020b). The sections were treated with mouse anti-caspase-3 antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight. The sections were incubated with the biotinylated mouse secondary antibody for another 1 hour. Vector Elite ABC kit (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used to amplify the secondary antibody. The sections were visualized by 0.02% diaminobenzidine, and the sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides. The slides were air-dried overnight at room temperature, and Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was used for coverslips.

Bax, Bcl-2, AMPK Western blotting

Western blot analysis for Bax, Bcl-2, and AMPK was done as the same method of Park et al. (2020). After homogenizing liver tissues on ice, the tissues were lysed using lysis buffer. Protein content was calculated using Bio-Rad colorimetric protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). After separation of 40-μg protein on sodium dodecyl sulfate-poly-acrylamide gels, it was transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane. Then, the reaction mixture was treated with primary antibodies such as mouse β-actin antibody (1:3,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse Bcl-2 antibody (1: 1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit Bax antibody (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit AMPK antibody (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies for β-actin and Bcl-2 and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies for Bax and AMPK were used as the secondary antibodies. The expression for bands was analyzed using enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Data analysis

One-way analysis of vairiance and Duncan post hoc test were used for data analysis. Results were expressed as mean±standard error of the mean, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

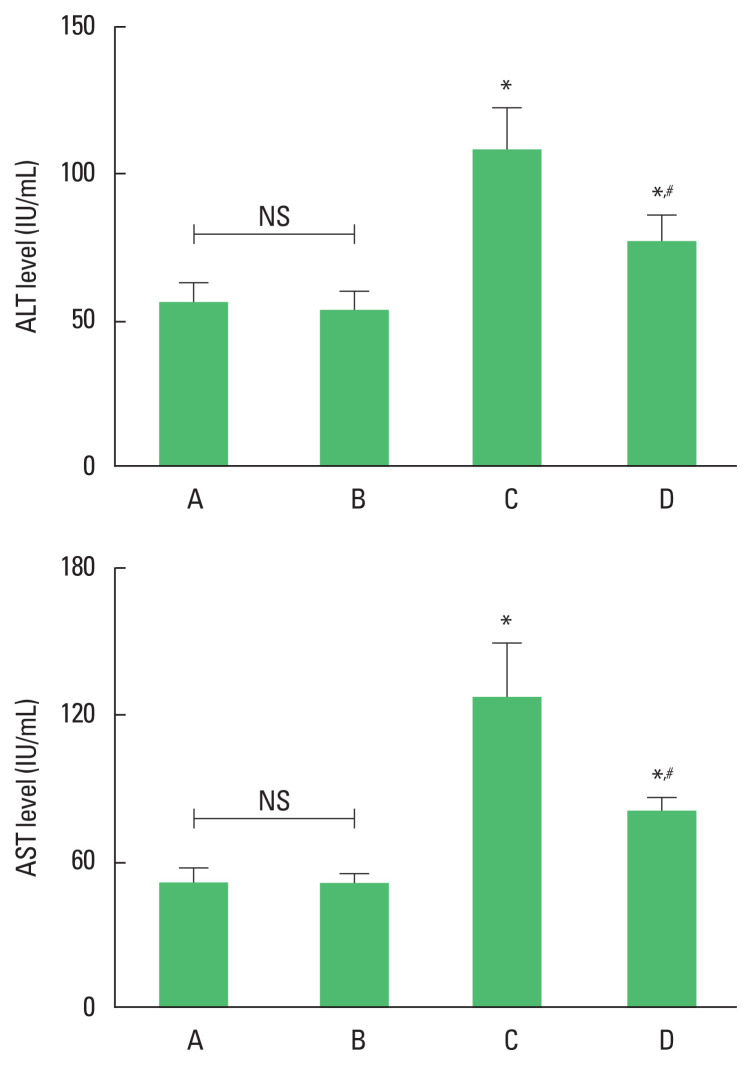

ALT and AST level

The level of ALT and AST was enhanced by ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application (P<0.05). However, ALT and AST level was suppressed by treadmill running (P<0.05) in the ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application mice. Treadmill running did not show significant effect on the ALT and AST level under normal conditions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The level of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Upper panel: ALT level. Lower panel: AST level. *P<0.05 compared to the control group. #P<0.05 compared to the exercise group. A, control group; B, exercise group; C, ethanol with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) application group; D, ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application and exercise group; NS, nonsignificant.

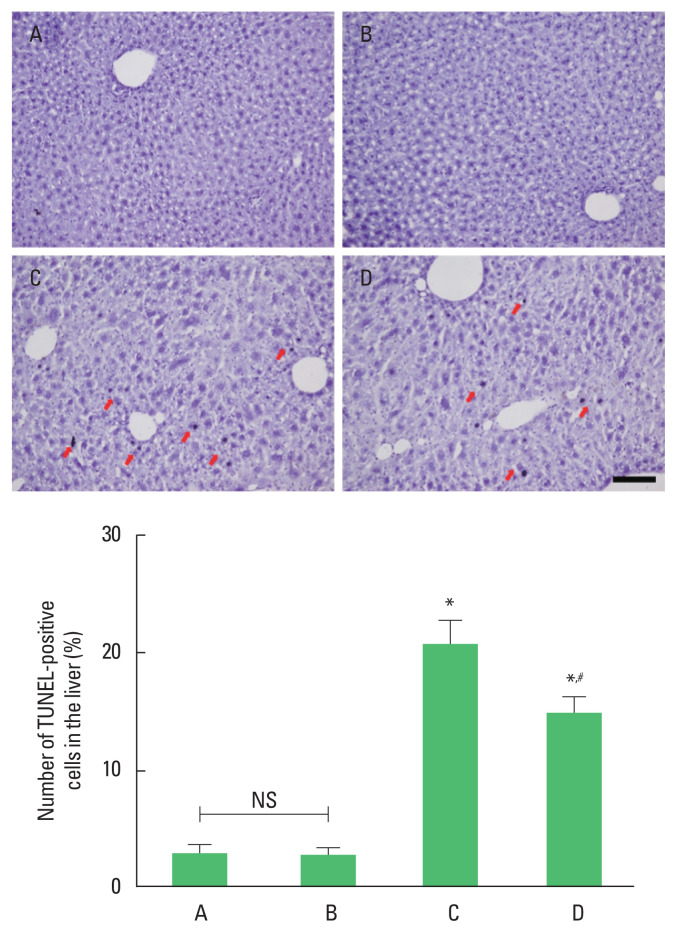

TUNEL-positive cell number

The number of TUNEL-positive cells was enhanced by ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application (P<0.05). However, TUNEL-positive cell number was suppressed by treadmill running (P<0.05) in the ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application mice. Treadmill running did not show significant effect on the TUNEL-positive cell number under normal conditions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The percentage of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells in the liver. Upper panel: photomicrographs of TUNEL-positive cells. Red arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. Scale bar represents 100 μm. Lower panel: number of TUNEL-positive cells in each group. *P<0.05 compared to the control group. #P<0.05 compared to the exercise group. A, control group; B, exercise group; C, ethanol with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) application group; D, ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application and exercise group; NS, nonsignificant.

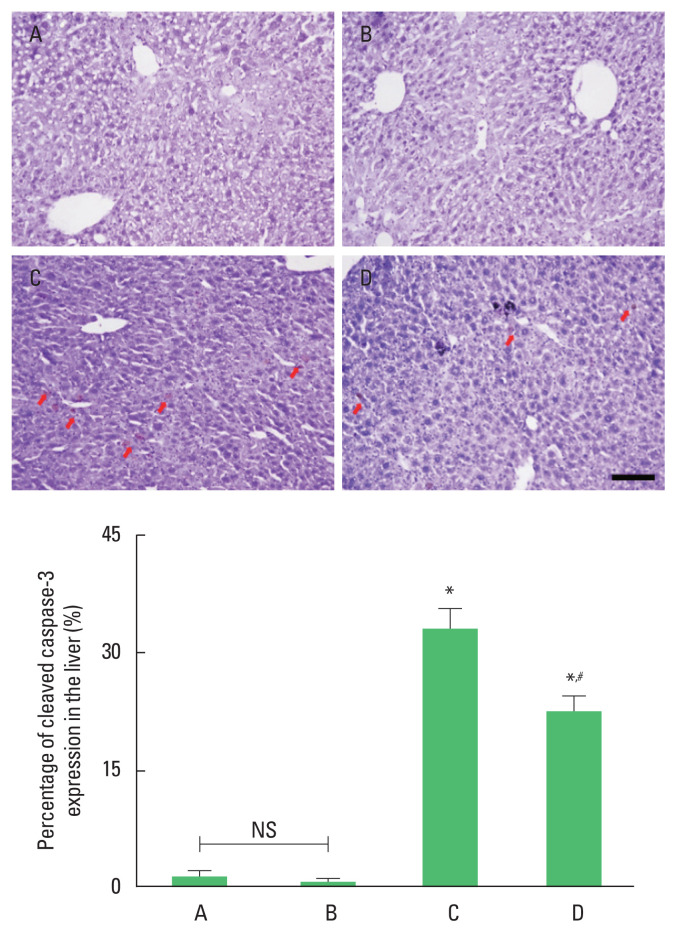

Cleaved caspase-3 expression

The expression of cleaved caspase-3 was enhanced by ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application (P<0.05). However, cleaved caspase-3 expression was suppressed by treadmill running (P<0.05) in the ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application mice. Treadmill running did not show significant effect on the cleaved caspase-3 expression under normal conditions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The percentage of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells in the liver. Upper panel: photomicrographs of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells. Red arrows indicate cleaved caspase-3-positive cells. Scale bar represents 100 μm. Lower panel: number of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells in each group. ns indicates nonsignificant. *P<0.05 compared to the control group. #P<0.05 compared to the exercise group. A, control group; B, exercise group; C, ethanol with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) application group; D, ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application and exercise group; NS, nonsignificant.

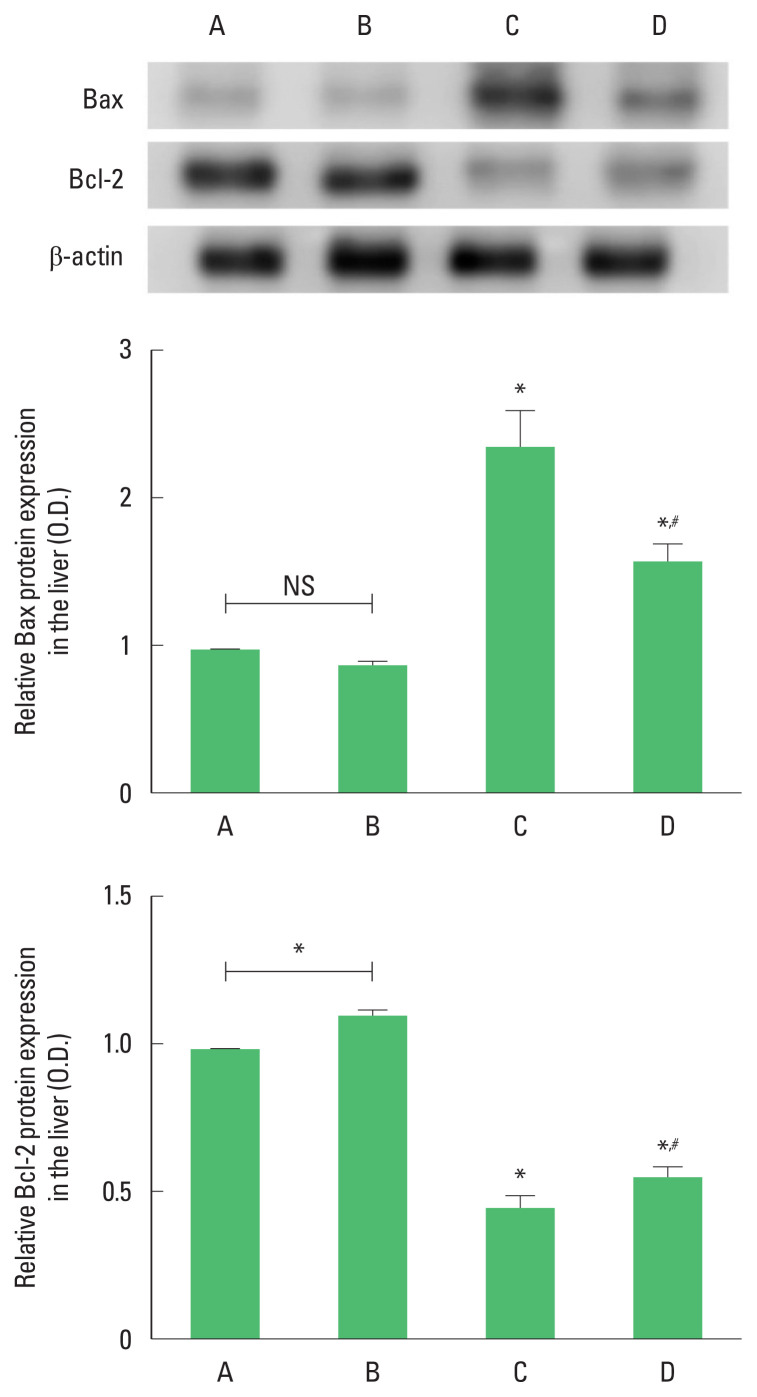

Bax and Bcl-2 expressions

The expression of Bax was enhanced and the expression of Bcl-2 was suppressed by ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application (P<0.05). However, Bax expression was suppressed and Bcl-2 expression was enhanced by treadmill running (P<0.05) in the ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application mice. Treadmill running exerted no significant effect on the Bax expression but enhanced Bcl-2 expression under normal conditions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The expressions of Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) in the liver. Upper panel: representative expressions of Bax and Bcl-2. Middle panel: relative expression of Bax in each group. Lower panel: relative expression of Bcl-2 in each group. ns indicates nonsignificant. *P<0.05 compared to the control group. #P<0.05 compared to the exercise group. A, control group; B, exercise group; C, ethanol with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) application group; D, ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application and exercise group; NS, nonsignificant.

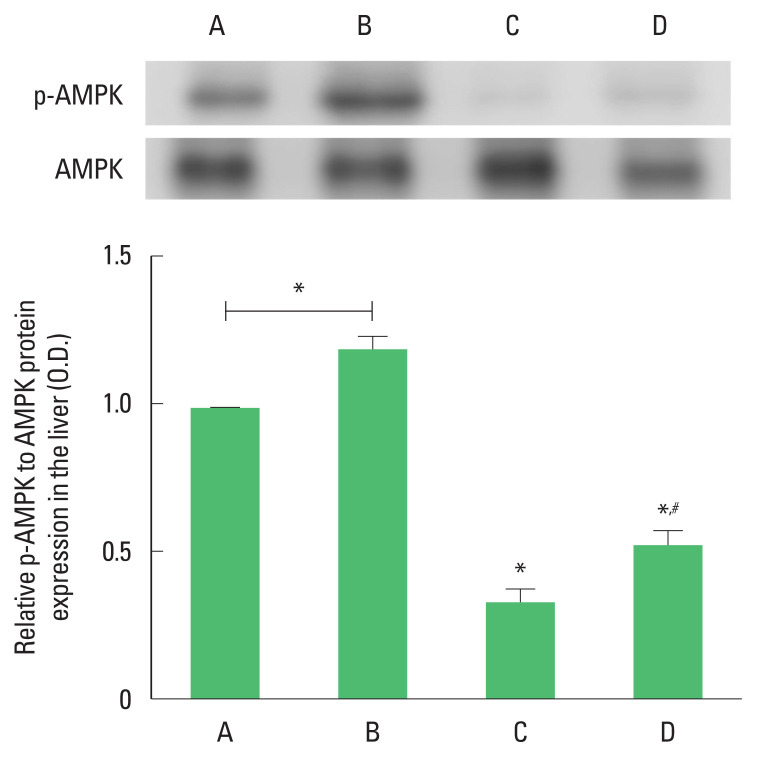

AMPK phosphorylation

The phosphorylation of AMPK was suppressed by ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application (P<0.05). However, AMPK phosphorylation was enhanced by treadmill running (P<0.05) in the ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application mice. Treadmill running enhanced AMPK phosphorylation under normal conditions (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The phosphorylation of 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in the liver. Upper panel: representative expression of AMPK. Lower panel: relative expression of AMPK in each group. *P<0.05 compared to the control group. #P<0.05 compared to the exercise group. A, control group; B, exercise group; C, ethanol with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) application group; D, ethanol with LPS and CCl4 application and exercise group.

DISCUSSION

Ethanol alone enhanced ALT and AST level in mice, whereas ethanol administration with LPS and CCl4 more potently enhanced ALT and AST level in mice (Kim et al., 2021). To induce acute liver injury, intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 into mice increased ALT and AST level (Lee et al., 2020a), and CCl4 injection to mice also increased ALT and AST level in serum (Ko et al., 2020). Decreased ALT and AST level indicates recovery of liver injury. From the current results, treadmill exercise ameliorated ethanol with LPS and CCl4-induced elevation of ALT and AST level.

TUNEL staining is an experimental method detecting DNA fragmentation generated in apoptotic process (Gorczyca et al., 1993). Social isolation in old rats enhanced the number of TUNEL-positive cells, representing that apoptotic cell death was accelerated by social isolation (Park et al., 2020). Treadmill running in old and obese mother rats decreased TUNEL-positive cell number, suggesting that treadmill running suppressed apoptotic cell death (Ko, 2021). Decreased TUNEL-positive cell number represents suppressed apoptosis. From the current results, treadmill exercise suppressed ethanol with LPS and CCl4-induced elevation of TUNEL- positive cell number.

Caspases activation is the final step of apoptosis process, and caspase-3 is a critical actor of apoptosis (Lee et al., 2020b). Caspase-3 expression in the hippocampus was enhanced in the socially isolated group compared to the control group (Song et al., 2018). However, treadmill running reduced caspase-3 expression in socially isolated rats (Song et al., 2018). Inhibition of caspase-3 expression indicates suppression of apoptosis. From the current results, treadmill exercise suppressed ethanol with LPS and CCl4-induced elevation of cleaved caspase-3 expression.

Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis, but Bcl-2 forms a heterodimer with Bax, resulting in loss of apoptosis inhibitory function (Kuwana and Newmeyer, 2003). In old rats subjected to social isolation, apoptosis was promoted by increasing Bax expression and decreasing Bcl-2 expression, but swimming exercise inhibited Bax expression and increased Bcl-2 expression to inhibit apoptosis (Park et al., 2020). Inhibition of Bax expression and enhancing of Bcl-2 expression means suppression of apoptosis. From the current results, treadmill exercise suppressed ethanol with LPS and CCl4-induced elevation of Bax expression. Treadmill exercise also enhanced Bcl-2 expression suppressed by application of ethanol with LPS and CCl4.

AMPK activation causes hepatic fatty acid oxidation, ketogenesis, cholesterol synthesis, adipogenesis, stimulation of skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation and glucose uptake, regulation of insulin secretion, and inhibition of triglyceride synthesis, adipocyte lipogenesis and lipolysis (Winder and Hardie, 1999). Adiponectin directly activates AMPK in the liver and musculoskeletal system, increases fatty acid oxidation, improves insulin resistance and causes anti-inflammatory property (Hada et al., 2007). AMPK plays an important role in modulating growth and metabolism and has been linked to autophagy and cell polarity (Mihaylova and Shaw, 2011). AMPK phosphorylation exerts protective role against ethanol with LPS and CCl4-induced liver damage. From the current results, treadmill exercise enhanced AMPK phosphorylation which was suppressed by application of ethanol with LPS and CCl4.

As a result of this experiment, it was found that running on the treadmill had the effect of preventing ethanol with LPS and CCl4- induced liver damage to some extent. Through this experiment, it was found that treadmill exercise has the effect of reducing liver damage caused by alcohol and or drug addiction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A01044808).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- Gorczyca W, Traganos F, Jesionowska H, Darzynkiewicz Z. Presence of DNA strand breaks and increased sensitivity of DNA in situ to denaturation in abnormal human sperm cells. Analogy to apoptosis of somatic cells. Exp Cell Res. 1993;207:202–205. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hada Y, Yamauchi T, Waki H, Tsuchida A, Hara K, Yago H, Miyazaki O, Ebinuma H, Kadowaki T. Selective purification and characterization of adiponectin multimer species from human plasma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Ko IG, Jin JJ, Hwang L, Kim BK, Baek SS. Study on the pathogenesis of liver injury caused by alcohol and drugs. J Exerc Rehabil. 2021;17:319–323. doi: 10.12965/jer.2142530.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko IG, Jin JJ, Hwang L, Kim SH, Kim CJ, Han JH, Lee S, Kim HI, Shin HP, Jeon JW. Polydeoxyribonucleotide exerts protective effect against CCl4- induced acute liver injury through inactivation of NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7894. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko YJ. Treadmill exercise alleviates short-term memory impairments of pups born to old and obese mother rats. J Exerc Rehabil. 2021;17:153–157. doi: 10.12965/jer.2142300.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD. Bcl-2-family proteins and the role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Won KY, Joo S. Protective effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide against CCl4-induced acute liver injury in mice. Int Neurourol J. 2020a;24(Suppl 2):S88–95. doi: 10.5213/inj.2040430.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Kim CJ, Shin MS, Lim BV. Treadmill exercise ameliorates memory impairment through ERK-Akt-CREB-BDNF signaling pathway in cerebral ischemia gerbils. J Exerc Rehabil. 2020b;16:49–57. doi: 10.12965/jer.2040014.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Energy intake and exercise as determinants of brain health and vulnerability to injury and disease. Cell Metab. 2012;16:706–722. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SS, Park HS, Kim TW, Lee SJ. Effects of swimming exercise on social isolation-induced memory impairment and apoptosis in old rats. J Exerc Rehabil. 2020;16:234–241. doi: 10.12965/jer.2040366.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayhan MA, Islam MK, Khatun MA, Islam D, Rahman MN. Remedial role of exercise training to deep-fried oil-induced metabolic and histological changes in Wistar rats. J Food Biochem. 2020;44:e13458. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shojaie L, Iorga A, Dara L. Cell death in liver diseases: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:9682. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SH, Jee YS, Ko IG, Lee SW, Sim YJ, Kim DY, Lee SJ, Cho YS. Treadmill exercise and wheel exercise improve motor function by suppressing apoptotic neuronal cell death in brain inflammation rats. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018;14:911–919. doi: 10.12965/jer.1836508.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Kisseleva T. Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;1:S60–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Song F, Li S, Wu B, Gu Y, Yuan Y. Salvianolic acid A attenuates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Bcl-2/Bax and caspase-3/cleaved caspase-3 signaling pathways. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:1889–1900. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S194787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder WW, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase, a metabolic master switch: possible roles in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E1–E10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.1.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YF, Bu FT, Yin NN, Wang A, You HM, Wang L, Jia WQ, Huang C, Li J. NLRP12 negatively regulates EtOH-induced liver macrophage activation via NF-κB pathway and mediates hepatocyte apoptosis in alcoholic liver injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106968. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]