Abstract

Some patients with myocardial infarction (MI) exhibit lymphopenia, a reduction in blood lymphocyte count. Moreover, lymphopenia inversely correlates with patient prognosis. The objective of this study was to elucidate the underlying mechanisms that cause lymphopenia after MI. Multiparameter flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that MI induced profound B and T lymphopenia in a mouse model, peaking at day 1 post-MI. The finding that non-MI control and MI mice exhibited similar apoptotic rate for blood B and T lymphocytes argues against apoptosis being essential for MI-induced lymphopenia. Interestingly, the bone marrow in day 1 post-MI mice contained more B and T cells but showed less B- and T-cell proliferation compared with day 0 controls. This suggests that blood lymphocytes may travel to the bone marrow after MI. This was confirmed by adoptive transfer experiments demonstrating that MI caused the loss of transferred lymphocytes in the blood, but the accumulation of transferred lymphocytes in the bone marrow. To elucidate the underlying signaling pathways, β2-adrenergic receptor or sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor type 1 (S1PR1) was pharmacologically blocked, respectively. β2-receptor inhibition had no significant effect on blood lymphocyte count, whereas S1PR1 blockade aggravated lymphopenia in MI mice. Furthermore, we discovered that MI-induced glucocorticoid release triggered lymphopenia. This was supported by the findings that adrenalectomy (ADX) completely prevented mice from MI-induced lymphopenia, and supplementation with corticosterone in adrenalectomized MI mice reinduced lymphopenia. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that MI-associated lymphopenia involves lymphocyte redistribution from peripheral blood to the bone marrow, which is mediated by glucocorticoids.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Lymphopenia, a reduction in blood lymphocyte count, is known to inversely correlate with the prognosis for patients with myocardial infarction (MI). However, the underlying mechanisms by which cardiac ischemia induces lymphopenia remain elusive. This study provides the first evidence that MI activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to increase glucocorticoid secretion, and elevated circulating glucocorticoids induce blood lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow, leading to lymphopenia.

Keywords: bone marrow, glucocorticoids, lymphocyte, lymphopenia, myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial infarction (MI)-induced chronic heart failure is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in developed counties. In-hospital survival rates for patients with MI have greatly improved over the past several decades because of timely reperfusion and other therapeutic strategies; however, many patients who survive an acute MI episode subsequently develop chronic heart failure, due to progressive maladaptive myocardial remodeling. The 5-year mortality rate for chronic heart failure remains close to ∼40% (1). Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms underlying the development and progression of chronic heart failure post-MI is an unmet medical need that has high significance.

Lymphopenia, also known as lymphocytopenia, is defined as a count of < 1,000 lymphocytes per microliter of blood in adults, or <3,000 lymphocytes per microliter of blood in children. Lymphopenia is commonly observed in infectious diseases (including COVID-19), blood cancer, autoimmune disorders, and in patients who have received steroid therapy, radiation, or chemotherapy (2–5). Accumulating clinical studies have shown that some patients with MI also exhibit lymphopenia; and more importantly, lymphopenia is positively associated with worse prognosis. In patients with acute chest pain, low lymphocyte count is related to an increased risk for developing MI (6). Lymphopenia is associated with a higher risk of microvascular obstruction and worse heart function in patients with MI (7–10). The fact that neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) serve as strong independent biomarkers to predict the prognosis of patients with MI also highlights the significance of blood lymphocyte count (11, 12). Since lymphocytes play important roles in regulating post-MI cardiac remodeling and repair, we speculate that MI patients with severe lymphopenia may have insufficient protective adaptive immunity, which is detrimental to postischemic myocardial wound healing. Although the significance of lymphopenia in patients with MI has been appreciated for more than two decades, the mechanisms by which cardiac ischemia triggers lymphopenia are largely unknown.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying lymphopenia after MI using a mouse model. Our data demonstrate that MI stimulates the release of glucocorticoids, which induces blood B and T lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow, resulting in lymphopenia. Therefore, targeting glucocorticoid pathways may attenuate lymphopenia in patients with MI and potentially improve patient prognosis.

METHODS

Mice

Adult (3–6 mo old) male C57BL/6J mice were used in this study. Animals were housed in a facility with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle and had free access to water and standard rodent chow. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Florida and were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

MI and Ischemia-Reperfusion

MI was induced by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery, as described previously (13, 14). Before surgery, sustained release buprenorphine (1 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously. Mice were anaesthetized with 1%–3% isoflurane, intubated, and ventilated with a standard rodent ventilator (Harvard Apparatus). Using a minimally invasive surgery, the thoracic cavity was opened through an incision between the 3rd and 4th intercostal space. The left anterior descending coronary artery was ligated with 8-0 nylon suture (AD Surgical, No. XXS-N807T6) placed 1–2 mm distal to the left atrium. Infarction was confirmed by visualizing myocardium blanching. The thoracic cavity and skin were closed using 6-0 polypropylene suture (AD Surgical, No. S-P618R13). Non operated naïve mice served as day 0 controls as our previous study shows that day 0 could replace sham as MI controls (15). For myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R), the left anterior descending coronary artery was occluded for 45 min, followed by reperfusion for 24 h. Sham controls underwent the same procedure without artery occlusion. To avoid the impact of diurnal oscillations on blood leukocytes (16, 17), all animal surgeries and tissue collection were performed in the same time window (8:00 AM to 12:00 PM) of the day. Mice were euthanized with 3% inhalational isoflurane, followed by exsanguination and removal of the heart.

Infarct Area Measurement

At euthanasia, the heart was flushed with cardioplegic solution to arrest the heart in diastole and resected as aforementioned (14, 18). The left ventricle (LV) was sliced into apex, middle, and base pieces, and stained with 1% 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma-Aldrich, T8877) for 5 min at 37°C. Infarct area was calculated as the percentage of infarct area (white color) to total LV area using Photoshop (Adobe) (14).

Single Cell Preparation and Flow Cytometry

At different euthanasia time points, mouse blood was collected into EDTA tubes (BD Biosciences, 365974) via cardiac puncture. Whole blood was stained with a panel of antibodies against CD45 (BioLegend, 103108), CD11b (BioLegend, 101212), Ly6G (BioLegend, 127608), CD3 (BioLegend, 100222), CD19 (BioLegend, 115549), CD4 (BioLegend, 100430), and CD8 (BioLegend, 100743) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with red blood cell lysis/fixation solution (Biolegend, 422401) for 15 min at room temperature. To measure absolute cell count, precision count beads (BioLegend, 424902) were added to blood samples.

The entire LV was minced and dissociated into single cell suspension with a cocktail of collagenase II (Worthington Biochemical, CLS-2) and DNase I (Roche, 41407200) for 40–50 min at 37°C (13, 18). One lobe of the liver was dissociated with a mouse liver dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-105-807) using gentleMACS Octo dissociator with heaters. The spleen and mediastinal lymph node (mLN) were harvested. Single cell suspension was made by mashing tissues between the frosted ends of two microscope slides. Bone marrow cells were collected by flushing the femur with RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM EDTA (19) or centrifuging the femur (one-end cut) for 30 s at 10,000 g (20). After red blood cells were lysed (BioLegend, 420301), the cell suspension was stained with a panel of antibodies against CD45, CD11b, Ly6G, CD3, CD19, CD4, and CD8.

For flow cytometry experiments, isotype IgG served as negative staining controls. Dead cells were excluded using Zombie NIR fixable viability dye (BioLegend, 423105). The samples were run on flow cytometers LSRII (BD Biosciences) or Cytek Northern Lights (CYTEK), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software. Total cell count in the tissue was quantified using a Luna-II automated cell counter, and the numbers of different cells were calculated based on relative abundance obtained by flow cytometry (number = total cell count × percentage of positive cells).

Evaluation of Cell Apoptosis

Mouse blood was collected into EDTA tubes via cardiac puncture. Red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (Gibco, A1049201). The cells were stained with antibodies against CD45, CD11b, CD3, and CD19. Single cell splenocytes were acquired by mashing the spleen between the frosted ends of two microscope slides, followed by lysis of red blood cells. Cell apoptosis was then evaluated using an Annexin V apoptosis detection kit (BioLegend, 640934). Apoptosis was calculated as the percentage of Annexin V+ cells to total cells.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Femurs and tibias were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 2 days, decalcified in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 2 wk, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned longitudinally at 5 µm thickness. Immunohisto chemical staining was performed as described previously (19). B and T cells were stained with anti-CD19 (eBioscience, 14–0194-82) and anti-CD3 (R&D Systems, MAB4841) antibodies, respectively.

Analysis of Bone Marrow Lymphocyte Proliferation

Bone marrow cells were collected, as aforementioned. After lysing red blood cells, the single cell suspension was labeled with antibodies against CD45, CD11b, CD3, and CD19. Cell proliferation was then detected with Click-iT plus EdU flow cytometry assay kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C10646) following manufacturer’s instructions. Proliferation was calculated as the percentage of EdU+ lymphocytes to total lymphocytes.

Purification and Adoptive Transfer of Splenic Lymphocytes

The splenic cell suspension was made by mashing tissues between the frosted ends of two microscope slides. After lysing red blood cells, cells were incubated with CD11b microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-126-725) to deplete CD11b+ cells. CD11b− splenic cells were mostly composed of B and T cells, and the purity was ∼90%. Splenic lymphocytes were then labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE, BioLegend, 423801) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Adoptive transfer was performed by intravenous (tail vein) injection of 5 × 106 CFSE labeled lymphocytes immediately before MI.

Treatments

To block β2-adrenergic receptor activity, mice were administered intraperitoneally with ICI-118,551 hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, I127) at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight daily (21). To inhibit sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor type 1 (S1PR1) activity, FTY720 (Sigma-Aldrich, SML0700) was administered by daily intraperitoneal injection (3 mg/kg) (22). Both drugs were given twice (1 day before MI and the day of MI surgery), and the doses were based on previous studies (21, 22). These animals were euthanized 1 day after MI.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA in the hypothalamus was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596), and RNA was quantified using the NanoDrop ND-2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse transcription of RNA was performed using high capacity RNA to cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4387406), and gene expression was evaluated using Taqman gene expression master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4369016) plus individual primers for Il1b, Il6, Il12a, and Tnfa. The gene expression was normalized to the reference gene Gapdh and shown as fold change to control groups. MIQE guidelines were followed for PCR experiments and analysis (23).

Measurement of Plasma Corticosterone Levels

Mouse blood was collected into EDTA tubes via cardiac puncture. Plasma was acquired by centrifuging blood at 2,000 g for 15 min at room temperature. Plasma corticosterone concentration was measured using a corticosterone enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Enzo, ADI-900-097) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Adrenalectomy and Corticosterone Feeding

Mice were anaesthetized with 1%–3% isoflurane. Sustained release buprenorphine (1 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously before surgery. A flank incision below the ribs on both sides was made. Two adrenal glands were dissected from the surrounding fat pad and removed (24). After surgery, all animals were given free access to saline in drinking bottles to maintain sodium balance.

For certain adrenalectomized mice, corticosterone (Sigma-Aldrich, C2505, 70 μg/mL, equivalent to 10 mg/kg/day) dissolved in saline with 0.45% 2-hydroxypropyl cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich, 332593) was fed in lightproof drinking bottles during the period of experiments (25, 26). Corticosterone was prepared fresh every 3 days to prevent degradation. Control mice received saline with 0.45% 2-hydroxypropyl cyclodextrin.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE. For data that followed Gaussian distribution, multiple group comparisons were performed using ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test when SD was equal among groups or using Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA and Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons test when SD was not equal among groups. Two group comparisons were analyzed with parametric unpaired t test when both groups had the same SD or parametric unpaired t test with Welch’s correction when SD was not equal in both groups. For data that did not follow Gaussian distribution, multiple group comparisons were analyzed with the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Pearson’s correlation was performed to determine correlation coefficients. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8 software.

RESULTS

MI Causes Lymphopenia and Neutrophilia

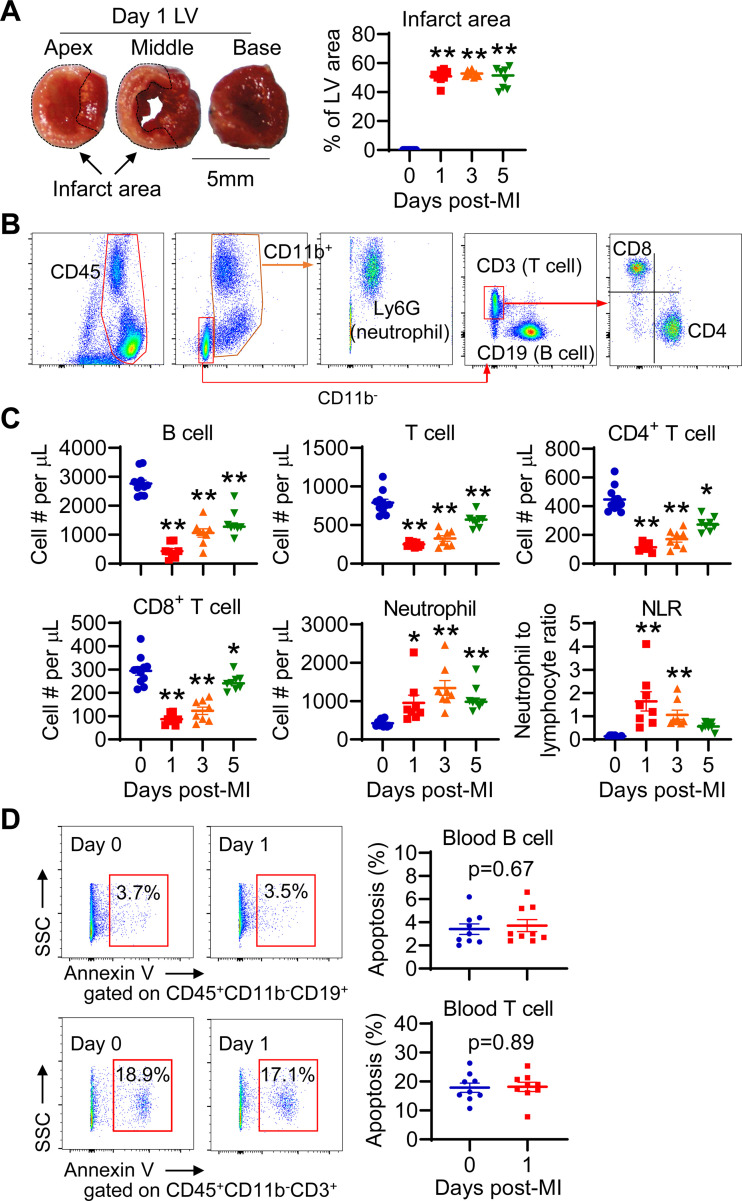

Lymphopenia and neutrophilia have been shown to occur in patients with MI (8, 10). To confirm them in animal models, we induced permanent ligation MI in mice. Mice at days 1, 3, and 5 post-MI showed comparable infarct area (Fig. 1A). We counted the numbers of peripheral blood leukocytes using multiparameter flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). The number of blood B and T cells was significantly reduced at days 1, 3, and 5 post-MI compared with non-MI day 0 controls (Fig. 1C). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells showed similar reduction, implying that MI-induced lymphopenia is a general response, not specific to certain phenotypes. Consistent with published findings (27), blood neutrophil numbers were significantly elevated after MI (Fig. 1C), leading to neutrophilia. Accordingly, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was drastically elevated at days 1 and 3 post-MI (Fig. 1C). Likewise, the percentage of B and T cells to leukocytes decreased, whereas neutrophil ratio was elevated following MI (Supplemental Fig. S1A, all supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17868560). To exclude the effect of surgery itself on blood lymphocytes, we compared naïve nonoperated and sham mice 24 h after operation. The data showed that sham surgery had minimal impact on blood B- and T-cell numbers (Supplemental Fig. S1B), confirming that lymphopenia is induced by MI. This gives us the rationale to use naïve day 0 mice as controls. In addition, the lymphopenia in MI mice was recapitulated in a mouse myocardial I/R model (Supplemental Fig. S2). Collectively, both MI and I/R induced B and T lymphopenia. Since lymphopenia peaked at day 1 after MI, we chose this time point for the following experiments.

Figure 1.

Myocardial infarction (MI) induces lymphopenia, which is not due to apoptosis. A: post-MI mice show similar infarct area. The left ventricle (LV) was cut into apex, middle, and base pieces, and stained with 1% 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride for infarct measurement. n = 8–11/group. **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. One-way ANOVA was used. B: gating strategy to identify distinct peripheral blood leukocytes with multiparameter flow cytometry. C: blood lymphocyte count decreases, whereas neutrophil count and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) increase after MI. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. Ordinary one-way ANOVA or nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used. D: days 0 and 1 MI mice exhibit comparable apoptotic (Annexin V+) B and T cells in blood, as evaluated by flow cytometry. n = 9/group. Unpaired t test was used.

MI Does Not Increase Blood Lymphocyte Apoptosis

Cell apoptosis has been shown to be involved in lymphopenia in cardiac arrest and resuscitation, sepsis, and other severe injuries (28, 29). For this reason, we evaluated the apoptosis of circulating lymphocytes using flow cytometry with Annexin V as an apoptotic marker. Interestingly, our data showed that day 0 control and day 1 MI mice displayed similar apoptotic rate for circulating B and T cells (Fig. 1D). This result argues against apoptosis as the major contributing factor for MI-induced lymphopenia.

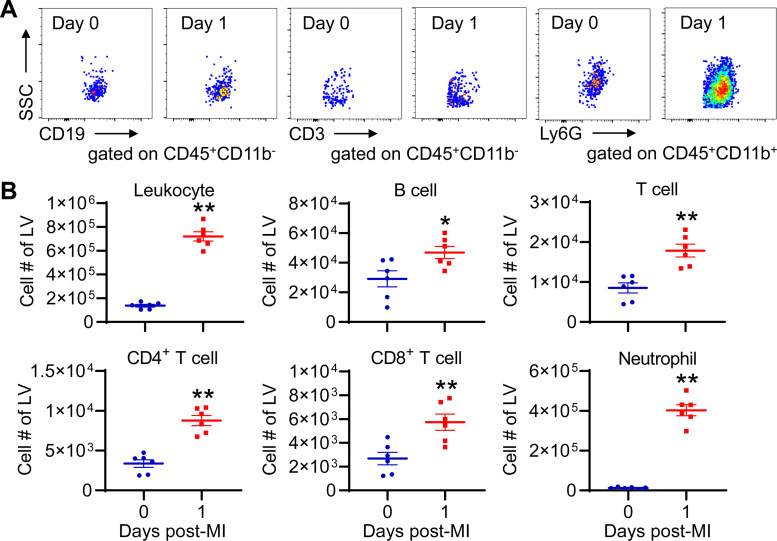

Lymphocyte Infiltration into Ischemic Myocardium at Day 1 post-MI Has Minor Contribution to MI-Associated Lymphopenia

It is well known that distinct leukocytes infiltrate the infarcted heart at different times after MI, with lymphocytes peaking at ∼7 days (30). In line with published findings (30), our data revealed that total leukocytes, B cells, T cells, and neutrophils were all significantly increased in day 1 LV than day 0 controls (Fig. 2, A and B). Of which, neutrophil number exhibited 30-fold increase, the biggest change among all leukocytes. This is consistent with the fact that neutrophil infiltration peaks at day 1 post-MI (18, 31). Quantitatively, ∼3×104 lymphocytes per mouse infiltrated the LV at day 1 post-MI; however, ∼5 × 106 blood lymphocytes per mouse (based on 2 mL of blood volume/mouse) were lost. Therefore, the lymphocyte infiltration into the ischemic myocardium is not the major reason for lymphopenia induced by MI.

Figure 2.

Lymphocytes and neutrophils infiltrate the ischemic myocardium at day 1 post-MI. A: representative dot plots showing different leukocytes in the left ventricle (LV) of day 0 and day 1 post-MI mice. Equal events were recorded for each group. B: leukocytes, B cells, T cells, and neutrophils in the LV are significantly increased at day 1 post-MI. n = 6/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. Unpaired t test was used. MI, myocardial infarction.

The liver is shown to upregulate cardioprotective proteins following MI (32, 33), indicative of heart-liver cross talk. To investigate whether blood lymphocytes are recruited to the liver post-MI, we assessed their content (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Interestingly, the liver in day 1 MI mice had less B cells than day 0 controls; by contrast, T-cell content showed no significant difference (Supplemental Fig. S3B). These data suggest that lymphocytes do not infiltrate the liver 1 day after MI.

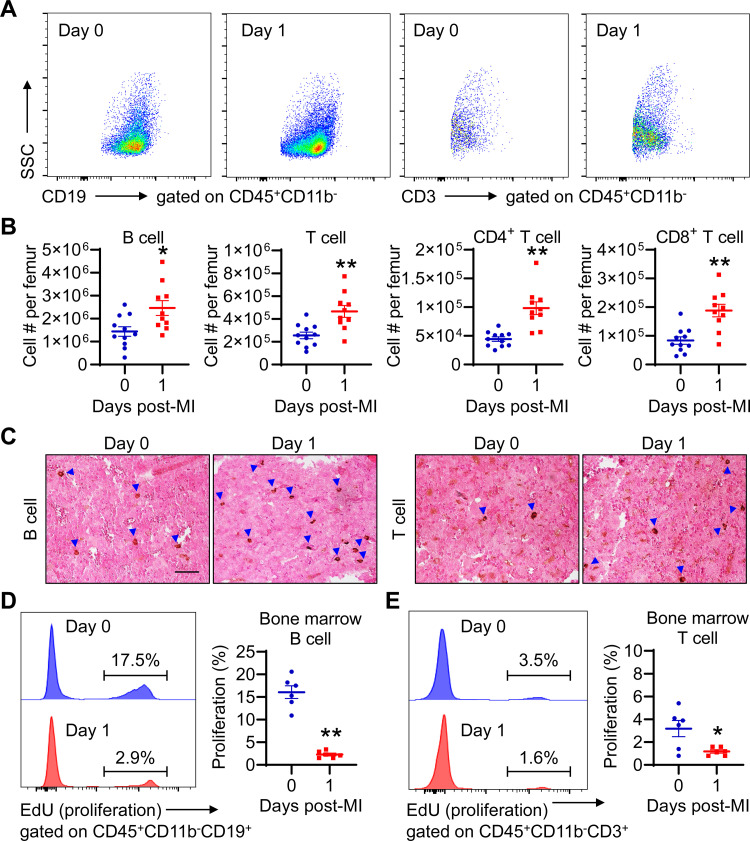

MI Causes Atrophy of the Spleen, which Contains Less B and T Lymphocytes Compared with Controls

The spleen and lymph nodes are secondary lymphoid organs that contain abundant lymphocytes. To determine whether blood lymphocytes migrate to the spleen and lymph nodes after MI, we compared the cell count in day 0 control and day 1 MI mice. Our data showed that the spleen in day 1 MI mice exhibited significant atrophy, lower cellularity, as well as less B and T lymphocytes than day 0 controls (Fig. 3A). To determine whether cell death promotes splenic atrophy, we evaluated splenocyte apoptosis. Unexpectedly, splenocyte apoptosis was actually reduced in day 1 MI mice compared with controls (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the heart-draining mLN did not show significant changes in terms of weight, cellularity, and B- and T-lymphocyte counts at day 1 post-MI (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that blood lymphocytes did not migrate to the spleen and mLN after MI; rather, the spleen showed lymphocyte loss.

Figure 3.

MI induces spleen atrophy and splenic lymphocyte loss. A: the spleen in day 1 MI mice shows atrophy and contains less B and T cells. n = 15/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. day (D) 0. Unpaired t test was used. B: flow cytometric analysis shows that splenocyte apoptosis is decreased after MI. Annexin V+ cells represent apoptotic cells. n = 8–11/group. *P < 0.05 vs. day 0. Unpaired t test was used. C: MI does not trigger atrophy and lymphocyte loss of heart-draining mediastinal lymph node (mLN). n = 5–6/group. Unpaired t test was used. MI, myocardial infarction.

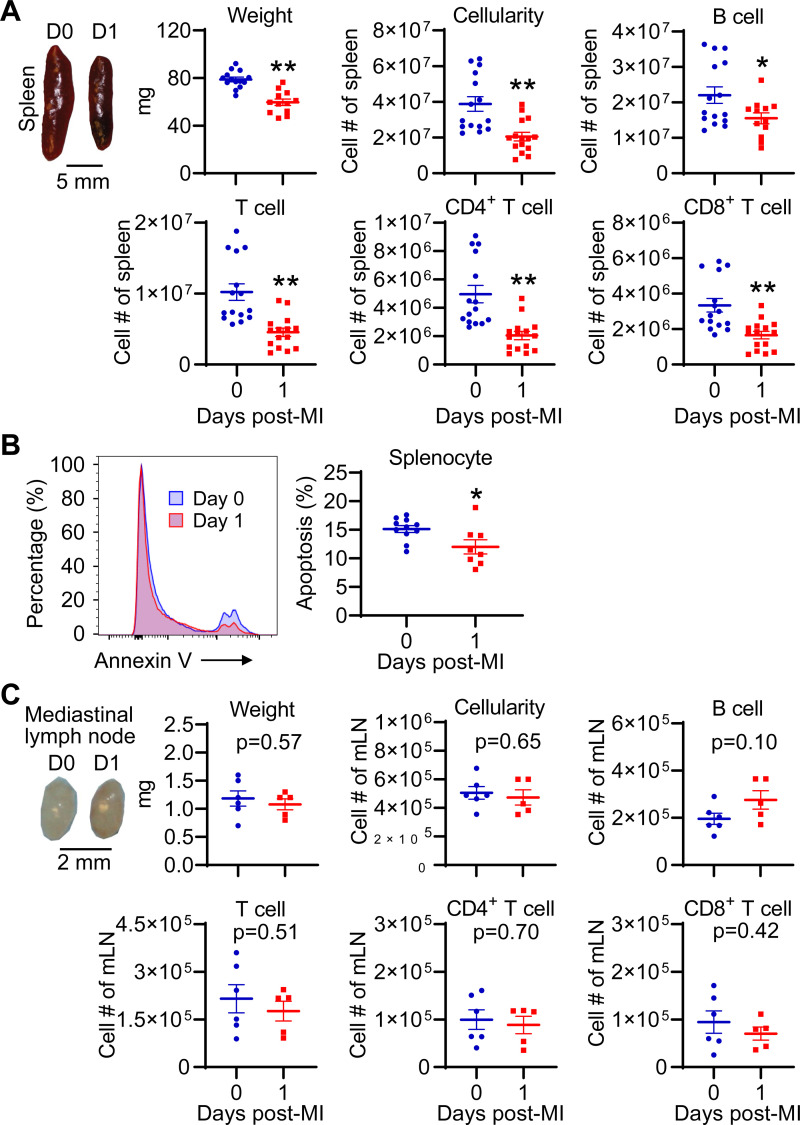

The Bone Marrow of Day 1 MI Mice Has More Lymphocytes than Controls

In addition to hematopoiesis, the bone marrow serves as a reservoir for regulatory T cells and CD8+ cells (34, 35). We therefore investigated if there is more lymphocyte accumulation in the bone marrow after MI. The data demonstrated that the bone marrow in mice at day 1 post-MI had more B and T cells than day 0 controls (Fig. 4, A and B). Immunohistochemical staining confirmed increased B and T lymphocytes in the bone marrow of day 1 MI mice (Fig. 4C). To determine whether lymphocyte proliferation contributes to their accumulation in the bone marrow post-MI, we evaluated B- and T-cell proliferation using flow cytometry with EdU as a proliferation marker. Under normal conditions, ∼16.1 ± 1.4% of B cells in the bone marrow was proliferative, which was reduced to 2.3 ± 0.3% at day 1 post-MI (Fig. 4D). T cell proliferation in the bone marrow was reduced from 3.2 ± 0.7% at day 0 to 1.2 ± 0.2% at day 1 post-MI (Fig. 4E). Thus, the more B and T lymphocytes in the bone marrow of day 1 MI mice were not due to increased cell proliferation. It is likely that they derive from peripheral blood.

Figure 4.

The bone marrow in day 1 MI mice contains more B and T cells. A: representative dot plots demonstrating B and T lymphocytes in the bone marrow of days 0 and 1 post-MI mice. Equal events were recorded for each group. B: B- and T-cell numbers are higher in the bone marrow of day 1 MI mice than that of day 0 controls. n = 10–11/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. Unpaired t test was used. C: representative images of immunohistochemical staining revealed increased B and T cells in the bone marrow of day 1 MI mice than day 0 controls. The blue arrow heads indicate B or T cells (brown dots). Scale bar, 50 µm. D: bone marrow B cells in day 1 MI mice have significantly lower proliferation (EdU+ cells) than day 0 controls. E: bone marrow T cells in day 1 MI mice exhibit lower proliferation than day 0 controls. n = 6/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. Unpaired t test was used. MI, myocardial infarction.

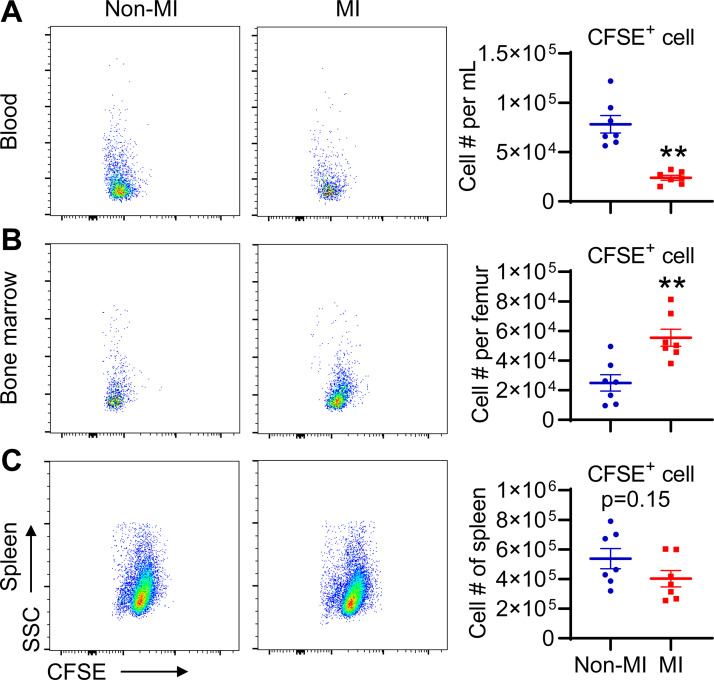

Adoptive Transfer Experiments Confirm That Blood Lymphocytes Migrate to the Bone Marrow after MI

To examine whether blood lymphocytes go to the bone marrow in response to MI, we performed adoptive transfer experiments. Splenic lymphocytes from naïve mice were purified with negative depletion of CD11b+ cells, and the purity of lymphocytes was ∼90% (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Purified lymphocytes were then labeled with CFSE (Supplemental Fig. S4B) and administered by tail vein injection. Within 30 min after transfer, both groups exhibited comparable blood CFSE+ cell count (Supplemental Fig. S4C), indicative of no difference in the number of transferred CFSE+ cells. The mice (red square in Supplemental Fig. 4C) were then subject to MI surgery, whereas the animals (blue dot) served as non-MI controls. After 24 h, MI mice had lower CFSE+ lymphocytes in the blood, but more CFSE+ lymphocytes in the bone marrow than non-MI controls (Fig. 5, A and B). In contrast, MI and non-MI control mice had comparable number of CFSE+ lymphocytes in the spleen (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these data confirm that blood lymphocytes migrate to the bone marrow after MI.

Figure 5.

MI causes the loss of blood CFSE+ lymphocytes and the accumulation of CFSE+ lymphocytes in the bone marrow. Equal volume of blood or equal events from tissue was recorded for each group. A: blood CFSE+ lymphocyte count is lower in day 1 MI mice than non-MI controls. n = 7/group. **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. B: bone marrow CFSE+ lymphocyte number is higher in day 1 MI mice than non-MI controls. n = 7/group. **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. C: splenic CFSE+ lymphocyte numbers are comparable in non-MI and day 1 MI mice. n = 7/group. Unpaired t test was used. CFSE, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester; MI, myocardial infarction.

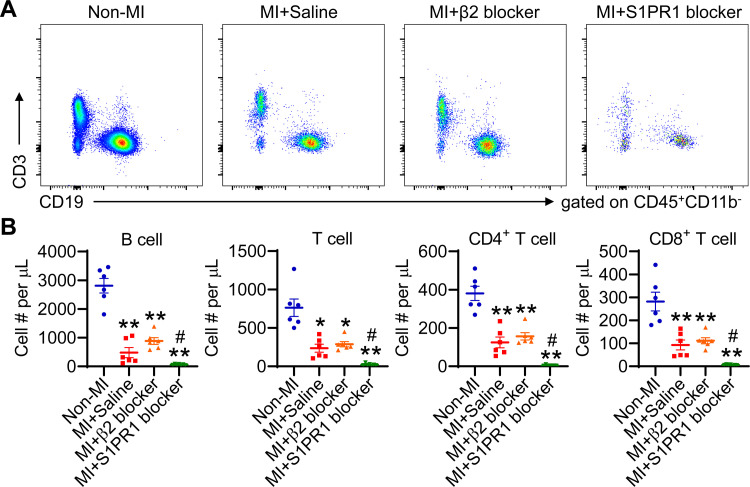

Blocking S1PR1 Activity Aggravates MI-Induced Lymphopenia

To decipher the signaling pathways that lead to MI-associated lymphopenia, we focused on β2-adrenergic receptor (36) and S1PR1 (37), both of which have been shown to modulate lymphocyte trafficking. We blocked these pathways respectively using specific receptor antagonist and then counted blood lymphocyte numbers. β2-adrenergic receptor blockade had no significant effect on MI-induced B and T lymphopenia, as shown in Fig. 6, A and B. In contrast, S1RP1 blockade further aggravated B and T lymphopenia induced by MI (Fig. 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

Blocking sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor type 1 (S1PR1) activity exacerbates MI-induced lymphopenia. Mice were treated with either β2-adrenergic receptor or S1PR1 blocker, respectively, with saline as negative controls. A: representative dot plots revealing blood B and T lymphocytes. Equal volume of blood was recorded for each group. B: β2-adrenergic receptor blockade has no significant effect on blood lymphocyte count, whereas S1PR1 blocker aggravates lymphopenia induced by MI. n = 6–7/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. non-MI controls, #P < 0.05 vs. MI+Saline. One-way ANOVA was used. MI, myocardial infarction.

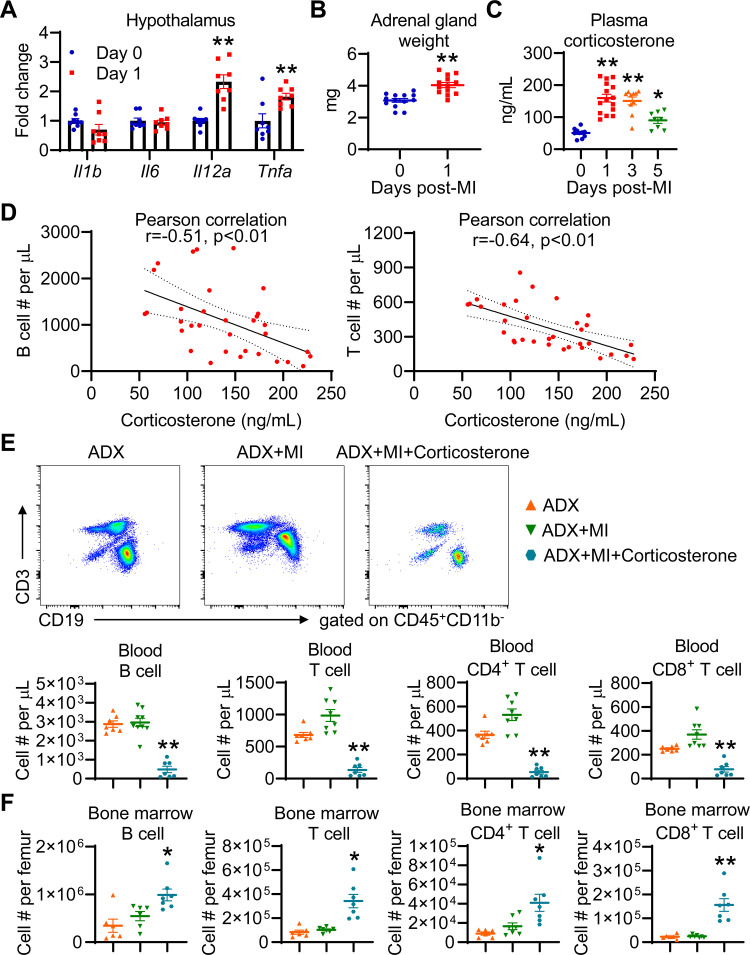

Adrenalectomy Prevents MI-Induced Lymphopenia, which Was Reversed by Glucocorticoid Administration

A wide range of insults, including infection (37), cardiac arrest and resuscitation (28), as well as stroke (21) are able to activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to release glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents), and glucocorticoids can induce lymphopenia. Therefore, we evaluated the HPA axis activation in MI mice. Compared with day 0 controls, day 1 MI mice showed higher mRNA expression of proinflammatory Il12a and Tnfa in the hypothalamus (Fig. 7A); in contrast, the mRNA expression of Il1b and Il6 in the hypothalamus was not affected by MI. Adrenal glands were significantly enlarged in MI mice than day 0 controls (Fig. 7B), confirming HPA axis activation. Correspondingly, plasma corticosterone levels were drastically elevated at days 1, 3, and 5 post-MI (Fig. 7C). Moreover, increased corticosterone levels in MI mice inversely correlated with blood B- and T-lymphocyte numbers (Fig. 7D), indicating that glucocorticoids may induce lymphopenia following MI.

Figure 7.

Glucocorticoids induce lymphopenia after MI. A: MI upregulates Il12a and Tnfa mRNA expression in the hypothalamus. n = 8/group. **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. Unpaired t test was used. B: MI significantly increases the weight of adrenal glands. n = 13/group. **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. Unpaired t test was used. C: plasma corticosterone levels are significantly increased at days 1, 3, and 5 post-MI. n = 8–15/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. day 0. One-way ANOVA was used. D: Pearson correlation analysis reveals that plasma corticosterone levels in post-MI mice negatively correlate with blood B- or T-cell count. n = 33. E: adrenalectomy (ADX) completely prevents MI-induced lymphopenia, which is reversed by corticosterone administration. For representative dot plots, equal volume of blood was recorded for each group. n = 7–9/group. **P < 0.01 vs. ADX+MI. One-way ANOVA was used. F: ADX prevents bone marrow B- and T-cell accumulation induced by MI, which is reversed by corticosterone administration. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. ADX+MI. One-way ANOVA was used. MI, myocardial infarction.

To determine a role for glucocorticoids in orchestrating lymphopenia after MI, mice underwent ADX, with two adrenal glands removed. The data demonstrated that ADX significantly decreased mouse plasma corticosterone levels from 53.9 ± 5.2 ng/mL at baseline to 3.8 ± 0.9 in adrenalectomized animals (Supplemental Fig. S5A). However, ADX per se did not significantly affect blood B- and T-lymphocyte numbers in naïve mice (Supplemental Fig. S5, B and C). As expected, ADX completely prevented MI-induced B and T lymphopenia and inhibited B- and T-cell accumulation in the bone marrow (Fig. 7, E and F).

In addition to glucocorticoids, adrenal glands secrete aldosterone, androgen, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. To uncover the direct contribution of glucocorticoids to lymphopenia induced by MI, adrenalectomized mice with MI were fed corticosterone. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S6A, corticosterone feeding significantly increased plasma corticosterone levels from 6.7 ± 2.0 ng/mL in ADX + MI mice to 77.5 ± 19.7 ng/mL in ADX + MI+Corticosterone mice. Although having no effect on infarct area (Supplemental Fig. S6B), corticosterone administration reinduced B and T lymphopenia and triggered B- and T-cell accumulation in the bone marrow (Fig. 7, E and F), phenocopying lymphopenia induced by MI. These data further confirm that glucocorticoids induce blood lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow after MI, causing lymphopenia.

DISCUSSION

Although lymphopenia is considered an independent prognostic marker for patients with MI, the mechanisms by which MI induces lymphopenia are unknown. Here, we describe that MI triggers severe B and T lymphopenia, which persist at least several days after MI. The decline in circulating lymphocytes after MI is not due to cells undergoing apoptosis or relocating to the liver or secondary lymphoid organs, such as the spleen and mLN. Rather, blood lymphocytes migrated to the bone marrow in response to MI, leading to lymphopenia. This process is mediated by HPA axis activation and increased release of glucocorticoids. This, to the best of our knowledge, is the first study to unveil the mechanisms underlying lymphopenia after MI.

Cell apoptosis contributes to lymphopenia in stroke (38) and cardiac arrest and resuscitation (28). Interestingly, we did not observe increased blood lymphocyte apoptosis in MI mice, suggesting that apoptosis did not play a key role in MI-induced lymphopenia. The fact that lymphopenia induced by Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection is not attributable to increased apoptosis indicates that apoptosis-associated lymphopenia is context dependent (37). Since MI does not increase blood lymphocyte apoptosis, we speculate that blood lymphocytes must have migrated to other organs and tissues. First, we quantified how many lymphocytes infiltrated the ischemic heart at day 1 post-MI and compared it with the number of lost blood lymphocytes. We found that the lymphocytes infiltrated the infarct heart at day 1 post-MI only accounted for 0.6% of lost blood lymphocytes. This suggests that the majority of blood lymphocytes went somewhere else. We also showed that lymphocytes did not infiltrate the liver at day 1 post-MI.

We next sought to focus on secondary lymphoid organs the spleen and lymph nodes, where lymphocytes are activated and proliferate to initiate adaptive immune responses (39). In agreement with published findings (40), the spleen at day 1 post-MI exhibited atrophy, lower cellularity, and less B and T lymphocytes. This is not due to apoptosis because day 1 MI mice showed lower splenocyte apoptosis than day 0 controls. The decreased apoptosis rate could be partially explained by activated neutrophils that might have a prolonged lifespan in inflammatory conditions. Indeed, spleen atrophy and lymphocyte loss were also observed in stroke (21), cardiac arrest and resuscitation (28), and infection (37). It is likely that splenic lymphocytes may also migrate to elsewhere in response to MI, phenocopying blood lymphocytes. In addition, splenic monocyte mobilization to the circulation after MI may also contribute to its atrophy (41). Blood T cell migration to peripheral LNs can cause T lymphopenia (36). For this reason, we evaluated the mLN that drains the heart. Interestingly, MI and non-MI control mice showed similar B- and T-cell numbers in the mLN at day 1 post-MI, indicating that circulating lymphocytes are not likely to accumulate in mLN. A previous study has shown that mLN T cells at day 7 post-MI have a higher proliferation rate (42). This makes sense because T cells are relatively late players and their peak infiltration into the ischemic heart occurs at 7 days after MI (30).

In humans, certain memory B cells generated during antigen responses migrate to the bone marrow (43). Following stroke, mature B cells from the periphery travel to the bone marrow (21). During dietary restriction, peripheral CD8+ memory T cells are redistributed to the bone marrow for priming (44). Our data demonstrated that the bone marrow in day 1 MI mice contained more B and T cells than day 0 controls. We then evaluated if increased lymphocyte production partially accounts for lymphocyte accumulation in the bone marrow of MI mice. Overall, T-cell proliferation was dramatically lower than that of B cells (2.3% for T cells vs. 16.1% for B cells) under baseline conditions. This is in line with the fact that B cells are produced in the bone marrow, whereas the thymus is the site for T-cell development and maturation. Furthermore, our data showed lower proliferation of B and T cells in MI mice than controls. These results suggest that the more B and T lymphocytes in the bone marrow of day 1 MI mice are not because of increased generation, probably derived from circulation. This hypothesis was confirmed by subsequent adoptive transfer experiments showing that MI caused the loss of transferred lymphocytes in the blood and the accumulation of transferred lymphocytes in the bone marrow.

A recent study reveals reactive vascular changes in the bone marrow following MI, including upregulated endothelial cell proliferation, increased endothelial numbers and vessel density, and elevated microvascular permeability (45). These vascular changes promote bone marrow myelopoiesis and production of neutrophils and monocytes. Although this study focused on days 2 to 6 post-MI, we speculate that some of those changes, especially increased microvascular permeability, likely occur at day 1 post-MI, which might trigger lymphocyte retention in bone marrow. Recurrent MI is shown to diminish bone marrow hematopoiesis and cardiac inflammation compared with a first MI (46). This is likely mediated by bone marrow macrophages expressing high levels of quiescence-promoting factors Vcam1 and Angpt1. Whether recurrent MI exacerbates or attenuates lymphopenia remains uninvestigated.

Continuous recirculation of the lymphocyte through lymphoid organs and peripheral blood is essential for immunosurveillance (47). β2-receptor and S1PR1 are two known pathways that regulate lymphocyte trafficking. Lymphocyte egress from LNs depends on S1PR1, through which lymphocytes detect high concentration of S1P in lymph to exit LNs (48). In addition, S1PR1 activation contributes to memory T-cell accumulation in the bone marrow during dietary restriction (44). Lymphocytes mainly express the β2-adrenergic receptor (49). Agonist stimulation of β2-receptor expressed on lymphocytes inhibits their egress from lymph nodes and rapidly causes lymphopenia in mice through enhancing retention-promoting signals CCR7 and CXCR4 (36). Interestingly, our results showed that pharmacological inhibition of β2-adrenergic receptor did not attenuate lymphopenia in MI mice, implying that β2-adrenergic receptor is not critical for lymphopenia induced by cardiac ischemia. This is also consistent with our data showing that blood lymphocytes did not accumulate in mLN following MI. In contrast, S1PR1 further decreased blood B- and T-lymphocyte count after MI. This might be because blockade of S1PR1 inhibited lymphocyte egress from LNs (48), and lymphocyte accumulation in LNs can cause lymphopenia (36). However, how S1PR1 blockade aggravates MI-induced lymphopenia needs to be revealed in future studies.

HPA axis activation and glucocorticoid release have been shown to participate in lymphopenia development in multiple diseases (21, 28, 37). B cell-specific deletion of glucocorticoid receptor rescues B lymphopenia and inhibits B-cell accumulation in the bone marrow after stroke (21). Pharmacological blockade of glucocorticoid receptor activity also attenuates lymphopenia in infection and cardiac arrest and resuscitation (28, 37). Patients with MI have higher cortisol levels (50, 51). Thus, we hypothesized that MI activates the HPA axis to induce glucocorticoid release, which triggers blood lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow and causes lymphopenia. We found that MI did activate the HPA axis, as evidenced by upregulated cytokine expression in the hypothalamus, enlarged adrenal glands, and dramatic increase in plasma corticosterone levels in MI mice. Pearson correlation analysis further indicated that plasma corticosterone levels negatively correlated with blood lymphocyte count. More importantly, blocking glucocorticoid release by ADX completely prevented mice from MI-induced lymphopenia and lymphocyte accumulation in the bone marrow, and supplementation with exogenous glucocorticoids phenocopied MI-induced lymphopenia. Taken together, these results prove our hypothesis that MI-induced glucocorticoid release leads to lymphopenia through a mechanism involving blood lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow. In line with our findings, a recent study shows that glucocorticoids orchestrate B-cell migration selectively between the bone marrow and blood (52). Although glucocorticoids have been reported to induce T-cell apoptosis (53), our data showed that increased plasma corticosterone levels in MI mice did not enhance lymphocyte apoptosis. It is likely that blood lymphocytes travel to the bone marrow to escape apoptosis induced by high levels of plasma glucocorticoids. However, the exact reason that peripheral lymphocytes migrate to the bone marrow in response to MI needs further investigation.

How local cardiac ischemia triggers distant HPA axis activation remains to be elucidated. Proinflammatory cytokines are known to induce HPA activation (54, 55). Our data showed that the hypothalamus in MI mice expressed higher levels of proinflammatory Il12a and Tnfa. One possibility is that MI-induced systemic inflammatory response is involved in post-MI HPA axis activation. In support of our data, cardiac arrest and resuscitation are also shown to upregulate proinflammatory cytokines in the hypothalamus (28). The chest pain and acute psychologic stress accompanied with MI could also be potential factors that activate the HPA axis. Although we showed that glucocorticoids induced peripheral lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow, it is unclear if glucocorticoids regulate chemotactic signaling or act directly on lymphocytes to modulate migration. Glucocorticoids are shown to upregulate CXCR4 expression on B and T lymphocytes and contribute to their migration from blood to the bone marrow (44, 52). Our flow cytometric analysis shows that MI upregulates CXCR4 expression on blood lymphocytes (data not shown). Therefore, future studies are warranted to investigate whether CXCR4 acts as a downstream molecule of glucocorticoids to regulate lymphocyte trafficking from blood to the bone marrow. In addition to lymphocyte apoptosis and trafficking, impaired lymphopoiesis has been shown to contribute to lymphopenia in other diseases (21, 37, 56). We could not rule out the possibility that reduced lymphopoiesis is involved in MI-induced lymphopenia, which is supported by our data showing that day 1 MI mice exhibited lower B and T proliferation in the bone marrow. Whether MI impairs lymphopoiesis that contributes to lymphopenia is an interesting question to address. Based on our data, lymphopenia tends to recover at day 5 post-MI. The reasons could be that the body resumes to generate more lymphocytes or lymphocytes trafficked to the bone marrow are released back to the peripheral blood.

Our study has several limitations. First, only male mice were used. One study reveals that women patients with MI present with higher peripheral lymphocyte count and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio than male patients (57). Whether sex differences exist in lymphocyte alterations in MI mice needs to be investigated. Second, MI is most prevalent in elderly population, and inflammatory processes in elderly are different from those in young individuals. Therefore, our findings need to be further expanded in aging animals. Third, our study focused mainly on day 1 post-MI. Given lymphocytes being relatively late players, future studies are warranted to unravel the role of lymphocytes in chronic stages post-MI.

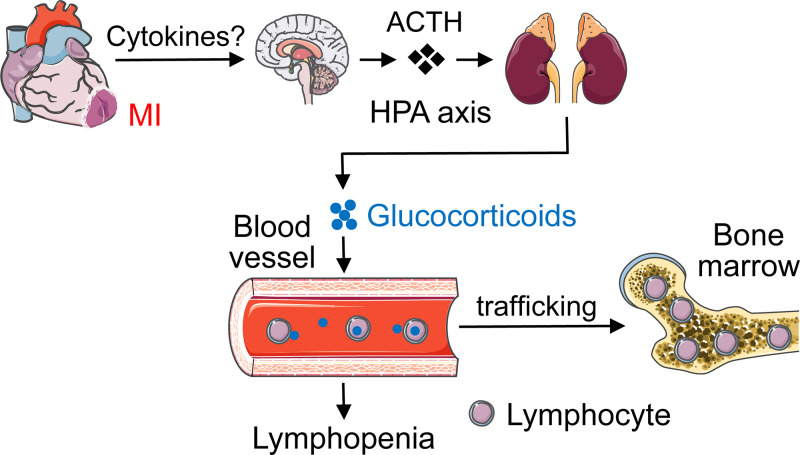

Taken together, our results unveil a previously unknown mechanism whereby heart-brain-immune system coordination induces lymphopenia following MI (Fig. 8). MI activates the HPA axis through an inflammation-related mechanism to enhance glucocorticoid secretion. Elevated circulating glucocorticoids induce blood lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow, causing lymphopenia. Persistent lymphopenia may cause insufficient protective adaptive immune response. It should be mentioned that distinct lymphocytes play different roles in post-MI cardiac repair. B lymphocytes impair cardiac function after MI by mobilizing monocytes (58). CD4+ T cells are beneficial (42, 59), whereas CD8+ T cells are deleterious to post-MI cardiac wound healing by affecting neutrophils, macrophages, and angiogenesis (60, 61). Therefore, inhibiting CD4+ T lymphopenia may potentially enhance protective CD4+ T-cell infiltration into the ischemic heart due to cell availability in the blood and ameliorate post-ischemic cardiac repair. One feasible and promising approach is to generate a mouse line with CD4+ T cell-specific deletion of glucocorticoid receptor and determine whether inhibiting CD4+ T lymphopenia would improve post-MI cardiac repair and function.

Figure 8.

A diagram showing how cardiac ischemia induces lymphopenia. MI activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis through an inflammation-related mechanism to enhance glucocorticoid secretion. Enhanced circulating glucocorticoids facilitate blood lymphocytes trafficking to the bone marrow, resulting in lymphopenia. Images of organs are from Servier Medical ART (https://smart.servier.com).

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Figs S1–S6: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17868560

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (R35 HL150732 to S.Y.Y.; R01GM142110 to S.Y.Y. and M.H.W.) and Department of Veterans Affairs (I01BX000799 and IK6BX004210 to M.H.W.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.M. and S.Y.Y. conceived and designed research; Y.M., N.V., A.R., and S.S. performed experiments; Y.M. analyzed data; Y.M., X.Y., N.V., V.C., A.R., S.S., M.H.W., and S.Y.Y. interpreted results of experiments; Y.M. prepared figures; Y.M. drafted manuscript; Y.M., X.Y., N.V., V.C., A.R., S.S., M.H.W., and S.Y.Y. edited and revised manuscript; Y.M., X.Y., N.V., V.C., A.R., S.S., M.H.W., and S.Y.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Charles Szekeres and Dr. Christopher Fleming for their technical support for the experiments involving flow cytometry. We also thank Ann Dickey for the assistance with tissue collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143: e254–e743, 2021. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng LL, Guan WJ, Duan CY, Zhang NF, Lei CL, Hu Y, Chen AL, Li SY, Zhuo C, Deng XL, Cheng FJ, Gao Y, Zhang JH, Xie JX, Peng H, Li YX, Wu XX, Liu W, Peng H, Wang J, Xiao GM, Chen PY, Wang CY, Yang ZF, Zhao JC, Zhong NS. Effect of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and lymphopenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 181: 71–78, 2021. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silzle T, Blum S, Schuler E, Kaivers J, Rudelius M, Hildebrandt B, Gattermann N, Haas R, Germing U. Lymphopenia at diagnosis is highly prevalent in myelodysplastic syndromes and has an independent negative prognostic value in IPSS-R-low-risk patients. Blood Cancer J 9: 63, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41408-019-0223-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merayo-Chalico J, Rajme-López S, Barrera-Vargas A, Alcocer-Varela J, Díaz-Zamudio M, Gómez-Martín D. Lymphopenia and autoimmunity: a double-edged sword. Hum Immunol 77: 921–929, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossman SA, Ellsworth S, Campian J, Wild AT, Herman JM, Laheru D, Brock M, Balmanoukian A, Ye X. Survival in patients with severe lymphopenia following treatment with radiation and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed solid tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 13: 1225–1231, 2015. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Núñez J, Sanchis J, Bodi V, Núñez E, Mainar L, Heatta AM, Husser O, Minana G, Merlos P, Darmofal H, Pellicer M, Llàcer A. Relationship between low lymphocyte count and major cardiac events in patients with acute chest pain, a non-diagnostic electrocardiogram and normal troponin levels. Atherosclerosis 206: 251–257, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boag SE, Das R, Shmeleva EV, Bagnall A, Egred M, Howard N, Bennaceur K, Zaman A, Keavney B, Spyridopoulos I. T lymphocytes and fractalkine contribute to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in patients. J Clin Invest 125: 3063–3076, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI80055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodí V, Sanchis J, Núñez J, Rumiza E, Mainar L, López-Lereu MP, Monmeneu JV, Oltra R, Forteza MJ, Chorro FJ, Llácer A. Post-reperfusion lymphopenia and microvascular obstruction in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Rev Esp Cardiol 62: 1109–1117, 2009. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)73325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ommen SR, Gibbons RJ, Hodge DO, Thomson SP. Usefulness of the lymphocyte concentration as a prognostic marker in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 79: 812–814, 1997. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragu R, Huri S, Zukermann R, Suleiman M, Mutlak D, Agmon Y, Kapeliovich M, Beyar R, Markiewicz W, Hammerman H, Aronson D. Predictive value of white blood cell subtypes for long-term outcome following myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis 196: 405–412, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, Diao J, Qi C, Jin J, Li L, Gao X, Gong L, Wu W. Predictive value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 18: 75, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0812-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azab B, Shah N, Akerman M, McGinn JT Jr.. Value of platelet/lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of all-cause mortality after non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis 34: 326–334, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11239-012-0718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsey ML, Jung M, Yabluchanskiy A, Cannon PL, Iyer RP, Flynn ER, DeLeon-Pennell KY, Valerio FM, Harrison CL, Ripplinger CM, Hall ME, Ma Y. Exogenous CXCL4 infusion inhibits macrophage phagocytosis by limiting CD36 signalling to enhance post-myocardial infarction cardiac dilation and mortality. Cardiovasc Res 115: 395–408, 2019. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma Y, Halade GV, Zhang J, Ramirez TA, Levin D, Voorhees A, Jin YF, Han HC, Manicone AM, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase-28 deletion exacerbates cardiac dysfunction and rupture after myocardial infarction in mice by inhibiting M2 macrophage activation. Circ Res 112: 675–688, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyer RP, de Castro Brás LE, Cannon PL, Ma Y, DeLeon-Pennell KY, Jung M, Flynn ER, Henry JB, Bratton DR, White JA, Fulton LK, Grady AW, Lindsey ML. Defining the sham environment for post-myocardial infarction studies in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H822–H836, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00067.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimba A, Cui G, Tani-Ichi S, Ogawa M, Abe S, Okazaki F, Kitano S, Miyachi H, Yamada H, Hara T, Yoshikai Y, Nagasawa T, Schutz G, Ikuta K. Glucocorticoids drive diurnal oscillations in T cell distribution and responses by inducing interleukin-7 receptor and CXCR4. Immunity 48: 286–298, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K, Hayano Y, Nakai A, Furuta F, Noda M. Adrenergic control of the adaptive immune response by diurnal lymphocyte recirculation through lymph nodes. J Exp Med 213: 2567–2574, 2016. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Y, Yabluchanskiy A, Iyer RP, Cannon PL, Flynn ER, Jung M, Henry J, Cates CA, Deleon-Pennell KY, Lindsey ML. Temporal neutrophil polarization following myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 110: 51–61, 2016. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Y, Zabell T, Creasy A, Yang X, Chatterjee V, Villalba N, Kistler EB, Wu MH, Yuan SY. Gut ischemia reperfusion injury induces lung inflammation via mesenteric lymph-mediated neutrophil activation. Front Immunol 11: 586685, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.586685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amend SR, Valkenburg KC, Pienta KJ. Murine hind limb long bone dissection and bone marrow isolation. J Vis Exp 110: 53936, 2016. doi: 10.3791/53936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Courties G, Frodermann V, Honold L, Zheng Y, Herisson F, Schloss MJ, Sun Y, Presumey J, Severe N, Engblom C, Hulsmans M, Cremer S, Rohde D, Pittet MJ, Scadden DT, Swirski FK, Kim DE, Moskowitz MA, Nahrendorf M. Glucocorticoids regulate bone marrow B lymphopoiesis after stroke. Circ Res 124: 1372–1385, 2019.doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanc CA, Grist JJ, Rosen H, Sears-Kraxberger I, Steward O, Lane TE. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor antagonism enhances proliferation and migration of engrafted neural progenitor cells in a model of viral-induced demyelination. Am J Pathol 185: 2819–2832, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55: 611–622, 2009. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prüss H, Tedeschi A, Thiriot A, Lynch L, Loughhead SM, Stutte S, Mazo IB, Kopp MA, Brommer B, Blex C, Geurtz LC, Liebscher T, Niedeggen A, Dirnagl U, Bradke F, Volz MS, DeVivo MJ, Chen Y, von Andrian UH, Schwab JM. Spinal cord injury-induced immunodeficiency is mediated by a sympathetic-neuroendocrine adrenal reflex. Nat Neurosci 20: 1549–1559, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nn.4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi S, Zhang B, Ma S, Gonzalez-Celeiro M, Stein D, Jin X, Kim ST, Kang YL, Besnard A, Rezza A, Grisanti L, Buenrostro JD, Rendl M, Nahrendorf M, Sahay A, Hsu YC. Corticosterone inhibits GAS6 to govern hair follicle stem-cell quiescence. Nature 592: 428–432, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03417-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Besnard A, Langberg T, Levinson S, Chu D, Vicidomini C, Scobie KN, Dwork AJ, Arango V, Rosoklija GB, Mann JJ, Hen R, Leonardo ED, Boldrini M, Sahay A. Targeting Kruppel-like factor 9 in excitatory neurons protects against chronic stress-induced impairments in dendritic spines and fear responses. Cell Rep 23: 3183–3196, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arruda-Olson AM, Reeder GS, Bell MR, Weston SA, Roger VL. Neutrophilia predicts death and heart failure after myocardial infarction: a community-based study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2: 656–662, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.831024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Q, Shen Y, Li R, Wu J, Lyu J, Jiang M, Lu L, Zhu M, Wang W, Wang Z, Liu Q, Hoffmann U, Karhausen J, Sheng H, Zhang W, Yang W. Cardiac arrest and resuscitation activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and results in severe immunosuppression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 41: 1091–1102, 2021. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20948612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girardot T, Rimmelé T, Venet F, Monneret G. Apoptosis-induced lymphopenia in sepsis and other severe injuries. Apoptosis 22: 295–305, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan X, Anzai A, Katsumata Y, Matsuhashi T, Ito K, Endo J, Yamamoto T, Takeshima A, Shinmura K, Shen W, Fukuda K, Sano M. Temporal dynamics of cardiac immune cell accumulation following acute myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 62: 24–35, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Y. Role of neutrophils in cardiac injury and repair following myocardial infarction. Cells 10: 1676, 2021. doi: 10.3390/cells10071676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu SQ, Tefft BJ, Roberts DT, Zhang LQ, Ren Y, Li YC, Huang Y, Zhang D, Phillips HR, Wu YH. Cardioprotective proteins upregulated in the liver in response to experimental myocardial ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H1446–H1458, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00362.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu SQ, Roberts D, Kharitonenkov A, Zhang B, Hanson SM, Li YC, Zhang LQ, Wu YH. Endocrine protection of ischemic myocardium by FGF21 from the liver and adipose tissue. Sci Rep 3: 2767, 2013. doi: 10.1038/srep02767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou L, Barnett B, Safah H, Larussa VF, Evdemon-Hogan M, Mottram P, Wei S, David O, Curiel TJ, Zou W. Bone marrow is a reservoir for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells that traffic through CXCL12/CXCR4 signals. Cancer Res 64: 8451–8455, 2004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazo IB, Honczarenko M, Leung H, Cavanagh LL, Bonasio R, Weninger W, Engelke K, Xia L, McEver RP, Koni PA, Silberstein LE, von Andrian UH. Bone marrow is a major reservoir and site of recruitment for central memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity 22: 259–270, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakai A, Hayano Y, Furuta F, Noda M, Suzuki K. Control of lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes through β2-adrenergic receptors. J Exp Med 211: 2583–2598, 2014. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen AL, Sun X, Wang W, Liu JF, Zeng X, Qiu JF, Liu XJ, Wang Y. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis contributes to the immunosuppression of mice infected with angiostrongylus cantonensis. J Neuroinflammation 13: 266, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0743-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prass K, Meisel C, Höflich C, Braun J, Halle E, Wolf T, Ruscher K, Victorov IV, Priller J, Dirnagl U, Volk HD, Meisel A. Stroke-induced immunodeficiency promotes spontaneous bacterial infections and is mediated by sympathetic activation reversal by poststroke T helper cell type 1-like immunostimulation. J Exp Med 198: 725–736, 2003. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruddle NH, Akirav EM. Secondary lymphoid organs: responding to genetic and environmental cues in ontogeny and the immune response. J Immunol 183: 2205–2212, 2009. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halade GV, Norris PC, Kain V, Serhan CN, Ingle KA. Splenic leukocytes define the resolution of inflammation in heart failure. Sci Signal 11:eaa01818, 2018. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aao1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, Figueiredo JL, Kohler RH, Chudnovskiy A, Waterman P, Aikawa E, Mempel TR, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science 325: 612–616, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hofmann U, Beyersdorf N, Weirather J, Podolskaya A, Bauersachs J, Ertl G, Kerkau T, Frantz S. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation 125: 1652–1663, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paramithiotis E, Cooper MD. Memory B lymphocytes migrate to bone marrow in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 208–212, 1997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins N, Han SJ, Enamorado M, Link VM, Huang B, Moseman EA, Kishton RJ, Shannon JP, Dixit D, Schwab SR, Hickman HD, Restifo NP, McGavern DB, Schwartzberg PL, Belkaid Y. The bone marrow protects and optimizes immunological memory during dietary restriction. Cell 178: 1088–1101.e15, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rohde D, Vandoorne K, Lee IH, Grune J, Zhang S, McAlpine CS, et al. Bone marrow endothelial dysfunction promotes myeloid cell expansion in cardiovascular disease. Nat Cardiovasc Res 1: 28–44, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s44161-021-00002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cremer S, Schloss MJ, Vinegoni C, Foy BH, Zhang S, Rohde D, Hulsmans M, Fumene Feruglio P, Schmidt S, Wojtkiewicz G, Higgins JM, Weissleder R, Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Diminished reactive hematopoiesis and cardiac inflammation in a mouse model of recurrent myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 75: 901–915, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakai A, Suzuki K. Adrenergic control of lymphocyte trafficking and adaptive immune responses. Neurochem Int 130: 104320, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cyster JG, Schwab SR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol 30: 69–94, 2012. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanders VM. The β2-adrenergic receptor on T and B lymphocytes: do we understand it yet? Brain Behav Immun 26: 195–200, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Güder G, Bauersachs J, Frantz S, Weismann D, Allolio B, Ertl G, Angermann CE, Störk S, Complementary and incremental mortality risk prediction by cortisol and aldosterone in chronic heart failure. Circulation 115: 1754–1761, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weir RA, Tsorlalis IK, Steedman T, Dargie HJ, Fraser R, McMurray JJ, Connell JM. Aldosterone and cortisol predict medium-term left ventricular remodelling following myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail 13: 1305–1313, 2011. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cain DW, Bortner CD, Diaz-Jimenez D, Petrillo MG, Gruver-Yates A, Cidlowski JA. Murine glucocorticoid receptors orchestrate B cell migration selectively between bone marrow and blood. J Immunol 205: 619–629, 2020. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashwell JD, Lu FW, Vacchio MS. Glucocorticoids in T cell development and function. Annu Rev Immunol 18: 309–345, 2000. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haddad JJ, Saadé NE, Safieh-Garabedian B. Cytokines and neuro-immune-endocrine interactions: a role for the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal revolving axis. J Neuroimmunol 133: 1–19, 2002. [Erratum in J Neuroimmunol 145: 154, 2003]. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bellavance MA, Rivest S. The HPA – immune axis and the immunomodulatory actions of glucocorticoids in the brain. Front Immunol 5: 136, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kong Y, Li Y, Zhang W, Yuan S, Winkler R, Krohnert U, Han J, Lin T, Zhou Y, Miao P, Wang B, Zhang J, Yu Z, Zhang Y, Kosan C, Zeng H. Sepsis-induced thymic atrophy is associated with defects in early lymphopoiesis. Stem Cells 34: 2902–2915, 2016. doi: 10.1002/stem.2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Blokland IV, Groot HE, Hendriks T, Assa S, van der Harst P. Sex differences in leukocyte profile in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients. Sci Rep 10: 6851, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63185-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zouggari Y, Ait-Oufella H, Bonnin P, Simon T, Sage AP, Guérin C, Vilar J, Caligiuri G, Tsiantoulas D, Laurans L, Dumeau E, Kotti S, Bruneval P, Charo IF, Binder CJ, Danchin N, Tedgui A, Tedder TF, Silvestre JS, Mallat Z. B lymphocytes trigger monocyte mobilization and impair heart function after acute myocardial infarction. Nat Med 19: 1273–1280, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rieckmann M, Delgobo M, Gaal C, Büchner L, Steinau P, Reshef D, Gil-Cruz C, Horst ENT, Kircher M, Reiter T, Heinze KG, Niessen HW, Krijnen PA, van der Laan AM, Piek JJ, Koch C, Wester HJ, Lapa C, Bauer WR, Ludewig B, Friedman N, Frantz S, Hofmann U, Ramos GC. Myocardial infarction triggers cardioprotective antigen-specific T helper cell responses. J Clin Invest 129: 4922–4936, 2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI123859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ilatovskaya DV, Pitts C, Clayton J, Domondon M, Troncoso M, Pippin S, DeLeon-Pennell KY. CD8(+) T-cells negatively regulate inflammation post-myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 317: H581–H596, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00112.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santos-Zas I, Lemarié J, Zlatanova I, Cachanado M, Seghezzi JC, Benamer H, Goube P, Vandestienne M, Cohen R, Ezzo M, Duval V, Zhang Y, Su JB, Bizé A, Sambin L, Bonnin P, Branchereau M, Heymes C, Tanchot C, Vilar J, Delacroix C, Hulot JS, Cochain C, Bruneval P, Danchin N, Tedgui A, Mallat Z, Simon T, Ghaleh B, Silvestre JS, Ait-Oufella H. Cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells promote granzyme B-dependent adverse post-ischemic cardiac remodeling. Nat Commun 12: 1483, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21737-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figs S1–S6: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17868560