Keywords: mechanical efficiency, mechanoenergetic cost, ovariectomy, sex difference

Abstract

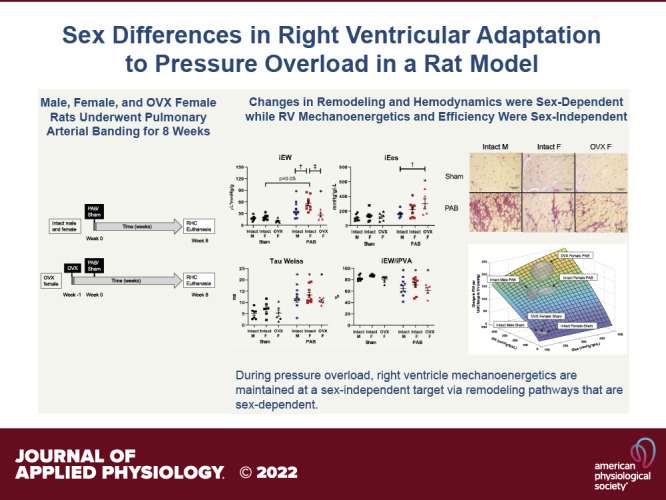

With severe right ventricular (RV) pressure overload, women demonstrate better clinical outcomes compared with men. The mechanoenergetic mechanisms underlying this protective effect, and their dependence on female endogenous sex hormones, remain unknown. To investigate these mechanisms and their impact on RV systolic and diastolic functional adaptation, we created comparable pressure overload via pulmonary artery banding (PAB) in intact male and female Wistar rats and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats. At 8 wk after surgery, right heart catheterization demonstrated increased RV energy input [indexed pressure-volume area (iPVA)] in all PAB groups, with the greatest increase in intact females. PAB also increased RV energy output [indexed stroke or external work (iEW)] in all groups, again with the greatest increase in intact females. In contrast, PAB only increased RV contractility-indexed end-systolic elastance (iEes)] in females. Despite these sex-dependent differences, no statistically significant effects were observed in the ratio of RV energy output to input (mechanical efficiency) or in mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood with pressure overload. These metrics were similarly unaffected by loss of endogenous sex hormones in females. Also, despite sex-dependent differences in collagen content and organization with pressure overload, decreases in RV compliance and relaxation time constant (tau Weiss) were not determined to be sex dependent. Overall, despite sex-dependent differences in RV contractile and fibrotic responses, RV mechanoenergetics for this degree and duration of pressure overload are comparable between sexes and suggest a homeostatic target.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Sex differences in right ventricular mechanical efficiency and energetic adaptation to increased right ventricular afterload were measured. Despite sex-dependent differences in contractile and fibrotic responses, right ventricular mechanoenergetic adaptation was comparable between the sexes, suggesting a homeostatic target.

INTRODUCTION

Sex differences influence the progression of right ventricular failure (RVF) secondary to pressure overload, which is the primary cause of death in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension secondary to left heart disease, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (1). In both the healthy and pressure-overloaded right ventricle (RV), women demonstrate superior RV systolic and diastolic function (2–6), which contributes to their better adaptation to and survival of pulmonary hypertension (PH) (3). Moreover, some of these sex differences in RV function with PH diminish with age (7, 8), which implicates age-related (i.e., menopausal) loss of endogenous sex hormone signaling in adaptive RV remodeling to pressure overload. Some experimental studies in rodent models of PH similarly have demonstrated superior female RV function (9, 10) and dependence on endogenous estrogen (10); however, some of these studies may have been confounded by sex differences in PH severity and RV afterload. A better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying sex differences in the pressure-overloaded RV is critical to treatment and management of RVF.

Cardiac mechanics, energy utilization, and their interactions are important clinical contributors to systolic and diastolic adaptation to pressure overload (11–16). Pressure overload increases RV wall tension such that the hemodynamic energy output generated by the RV in maintaining cardiac output is increased (17–19). To decrease wall tension, the RV undergoes hypertrophy and wall thickening, which lead to an adaptive increase in RV contractility (17). In the adapted RV, increased energy output is met with proportional increase in energy input (20). With disease progression, however, the RV myocardium undergoes additional remodeling processes, such as wall thinning and fibrosis, that impair the maintenance of enhanced RV contractility, and the RV begins to fail, which is evidenced by reduced cardiac output (19). During this stage, hemodynamic energy output is insufficient despite energy input, such that mechanical efficiency is reduced (21).

Mechanical efficiency, which is the ratio of energy output to energy input, is a holistic metric of ventricular function (22). Another, more novel, metric is the mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood (13), which is a function of ventricular afterload (Ea), end-systolic elastance (Ees), and stroke volume (SV). As defined mathematically by Kawaguchi et al., the mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood increases with Ea, because pressure overload raises myocardial oxygen consumption (13), and with Ees, because increased contractility increases oxygen consumption (23). This mechanoenergetic cost is sustained by metabolic energy generated by proper mitochondrial function (20, 24, 25). Interestingly, patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction demonstrated greater mechanoenergetic cost to deliver blood compared with age- and blood pressure-matched control subjects (13). Moreover, diastolic dysfunction increased with increased mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood (13).

The impacts of sex differences and endogenous female sex hormones on mechanical efficiency and mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood by the RV are unknown. We have previously shown that repletion of the female sex hormone estrogen increases mechanical efficiency in ovariectomized female rats with Sugen/hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (SuHx-PH) (26) and that the response of both the pulmonary vasculature and RV to SuHx is sex dependent (9, 10). To investigate the impact of sex and loss of endogenous female sex hormones on RV mechanics and energetics under comparable pressure overload conditions, we used a pressure overload model in which the degree of afterload increase [induced by pulmonary artery banding (PAB)] was normalized to the different body sizes in male and female animals. This approach generated comparable RV pressure overload in intact males and females as well as ovariectomized (OVX) females, which we then used to investigate the sex-dependent and female sex hormone-dependent mechanoenergetic adaptation of the RV to pressure overload.

METHODS

Animal Studies

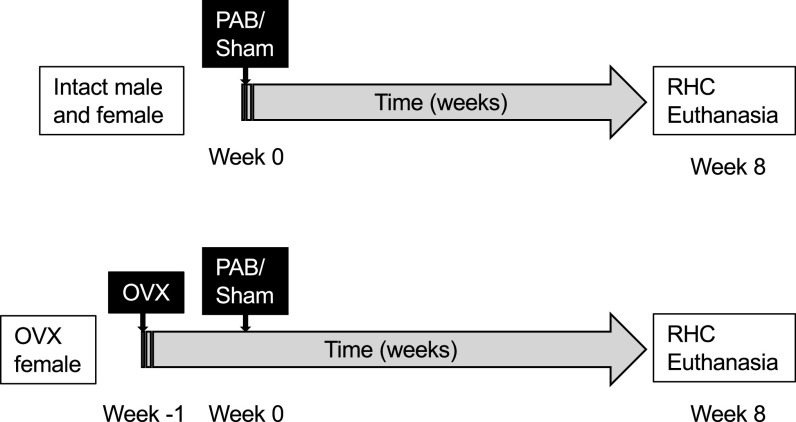

A total of 36 8-wk-old female Wistar rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were used in this study, 18 of which were ovariectomized (OVX) and 18 of which remained intact. Animals were ovariectomized between 6 and 7 wk of age (week −1). At week 0, all animals underwent a thoracotomy in which the main pulmonary artery (PA) diameter was directly measured with a spring divider and calipers. Animals were then randomly assigned to undergo either PAB (OVX: n = 8, intact: n = 9) or sham surgery (Sham; OVX: n = 10, intact: n = 9; see below for details). All animals were monitored weekly for signs and symptoms of RV failure including dyspnea, palpable ascites, inactivity, and ruffled fur (21, 27) until 8 wk after surgery. OVX rats were fed a soybean-free chow (Teklad 2020x; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) during the entire study to preclude potential confounding effect of dietary endogenous hormones. At the terminal time point, we confirmed the lack of ovaries in OVX rats. To assess RV-specific sex differences in the setting of PAB, we compared the resulting hemodynamic, biochemical, and histological data to those collected in male Wistar rats (Sham: n = 9, PAB: n = 10) published previously (21) in which identical surgical, animal care, and measurement procedures were used. A timeline and overview of the experimental groups is provided in Fig. 1. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and timeline of the described experiments. Pulmonary artery banding (PAB) or sham surgery was performed in age-matched intact male, intact female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female Wistar rats. Eight weeks after surgery, right heart catheterization (RHC) was performed before animals were euthanized for tissue harvest.

Pulmonary Artery Banding and Sham Surgery

PAB and sham surgeries were performed through a lateral thoracotomy and dissection of the main PA as described before (21). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% and then maintained at 2–3%, balance oxygen), intubated, and ventilated. Rats randomly assigned to the PAB group had a silk suture tied around the main PA and a reference needle to achieve ∼60–70% constriction based on the direct measurement of the PA. Rats assigned to the Sham group did not have the PA suture tied in place. Rats were monitored weekly for body weight (BW) changes and appearance for up to 8 wk after surgery.

Pressure-Volume Measurements

Terminal invasive right heart catheterization was performed to assess RV function as previously described (21). Rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.6 g/kg ip), intubated, and ventilated. Systemic pressure was measured with a pressure catheter (Millar, Houston, TX) positioned at the aortic arch inserted through the right carotid artery. RV pressure and volume (PV) were measured with a 1.9 F 6-mm-spacing PV catheter (Transonic Scisense, London, ON, Canada) inserted into the RV through the apex of the heart after removal of the chest wall. Measurements were recorded on Notocord Systems (Croissy-sur-Seine, France). After baseline recordings, at least three inferior vena cava (IVC) occlusions were performed to obtain end-systolic PV relationships.

Terminal Surgery

Two OVX PAB rats did not survive urethane anesthesia; postmortem examination indicated significant abdominal fluid and hypertrophied right atria (139.6 ± 26.2 mg OVX PAB vs. 38.1 ± 3.0 mg OVX Sham). Also, one of these two rats had significant liver discoloration and enlargement, suggestive of hepatic congestion. Tissues from these two rats were harvested and included in RV hypertrophy calculation, histology, and biochemical assays, but no hemodynamic data could be collected.

Pressure-Volume Calculations

With RV PV waveforms, baseline hemodynamic end points were determined, including RV end-systolic pressure (Pes), end-diastolic pressure (Ped), end-diastolic volume (Ved), end-systolic volume (Ves), and isovolumic relaxation time constant (tau Weiss). In cases where PV loop distortion occurred, Ved was taken as the midpoint between the maximum and minimum values recorded during isovolumic contraction. Ees was determined by calculating the slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship measured during IVC occlusion. Ea, a measurement of RV afterload, was calculated by taking the ratio of Pes and stroke volume (SV). Because of significant body weight differences between females and males (Table 1), volume-based metrics were indexed to terminal body weight to better reflect differences in the RV and arterial properties with sex and loss of endogenous sex hormones. Indexed parameters include end-systolic volume (iVes), end-diastolic volume (iVed), stroke volume [stroke volume index (SVI)], cardiac output [cardiac index (CI)], RV chamber compliance (ΔV/ΔP), iEa, iEes (derived from vena cava occlusions), external work (iEW, energy output), and pressure-volume area (iPVA, energy input). EW, calculated with the product of SV and RV end-systolic pressure (Pes), is an estimate of the mechanical energy used during contraction, whereas PVA is a measure of total mechanical energy generated during a cardiac cycle (28). RV mechanical efficiency was assessed as iEW/iPVA (31–33).

Table 1.

Estrogen levels, body weights, and body weight gain in experimental groups

| Parameter | Sham |

PAB |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Male | Intact Female | OVX Female | Intact Male | Intact Female | OVX Female | |

| Tibia length, mm | 44.3 ± 0.9 | 47.0 ± 1.1 | 43.0 ± 0.8 | 45.4 ± 1.2 | ||

| Initial body weight, g | 267.38 ± 6.46 | 187.78 ± 4.62† | 254.00 ± 7.94‡ | 262.60 ± 2.35 | 181.89 ± 4.78† | 239.25 ± 8.85†‡ |

| Terminal body weight, g | 469 ± 21 | 272 ± 8† | 366 ± 14†‡ | 455 ± 8 | 268 ± 8† | 346 ± 9†‡ |

| Body weight gain, % | 75 ± 6 | 45 ± 3† | 44 ± 3† | 73 ± 3 | 48 ± 2† | 45 ± 2† |

| Serum 17-β estradiol, pg/mL | 5.27 ± 0.66 | 14.11 ± 6.58 | 2.92 ± 0.33 | 5.82 ± 0.72 | 7.45 ± 2.13 | 2.66 ± 0.28 |

Values are presented as means ± SE. PAB, pulmonary artery banding; Sham, sham surgery. n = 8–10 animals per group. P < 0.05 for †female [intact or ovariectomized (OVX)] vs. male and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference multiple comparison correction).

Model-Based Prediction of RV Mechanoenergetic Cost to Pump Blood

To describe ventricular adaptation, we used a model developed previously by Kawaguchi et al. (13). Briefly, the mechanoenergetic cost to deliver blood is defined mathematically as the differential change in PVA with respect to SV or . Like the measured PVA, this continuously differential form of PVA, which we denote PVA, includes both productive work [stroke work (SW)] and nonproductive work [potential energy (PE) = PVA − SW]. If the change in PVA per unit SV increases, the cost to deliver a given amount of blood increases. If the PVA stays constant as SV increases, the cost to deliver blood decreases. To define the dependence of PVA on SV such that can be derived, the following relationships are used per Refs. 29–32:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where V0 is the volume axis intercept of the end-systolic pressure-volume relation. These equations are first rearranged to compute SV in terms of iEes and iEa:

| (3) |

and then, given the following defining equations,

| (4) |

| (5) |

we can obtain an expression for PE in terms of Pes and Ees:

| (6) |

such that PVA can be expressed in closed form as a function of SV (20, 31–33):

| (7) |

Finally, this expression for PVA can be differentiated with respect to SV and expressed in terms of iEes and iEa to obtain

| (8) |

Note that the final expression for is independent of measured SV, although dependent on Ved − V0.

This expression for the mechanoenergetic energy cost to pump blood was calculated for each animal. The results were plotted on a three-dimensional (3-D) surface with iEes as the x-axis, iEa as the y-axis, and as the z-axis with the average value for each experimental group the centroid of an elliptical surface and the boundary defined by the standard error of the mean.

17β-Estradiol Serum Concentration Measurement

After hemodynamic data collection, rats were euthanized and ∼1.5 mL of blood was collected. Blood samples were spun at 4,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. Serum samples were thawed on ice for 17β-estradiol measurement using the Calbiotech Mouse/Rat Estradiol ELISA Kit (El Cajon, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions and as performed previously (9).

Gross Histological Evaluation

After blood was collected, the heart was excised. RV free wall was separated from the LV and septum and weighed. RV hypertrophy was calculated as the RV weight scaled to the sum of LV and septal weights (Fulton index). The RV was sectioned for further histological and biochemical assessments. Postmortem evaluation confirmed the absence of ovaries and a shrunken uterus in all OVX female rats.

Histology and Image Analysis

A section of RV was fixed in 10% (vol/vol) formalin, preserved in 70% ethanol, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to visualize cardiomyocytes (8) or Picrosirius red to visualize collagen (21). RV cardiomyocytes were identified and cross-sectional area (CSA) was manually measured with ImageJ (version 1.49v; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) in at least four representative fields of view. Collagen deposition in the RV was identified by color thresholding with MetaVue (Optical Analysis Systems) in at least nine representative images. To quantify overall percentage of collagen content, the area containing interstitial collagen was divided by the tissue area in each field of view. Thick, tightly packed collagen and thin, loosely aligned collagen were identified as different interference colors under polarized light, with thick collagen defined as red, orange, or yellow color and thin collagen as green color (34–36). The ratio of thick to thin collagen fiber bundles was calculated for each image and averaged to obtain a single measurement for each rat. All histological analyses were performed by two observers blinded to sex and experimental condition.

Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

RNA was extracted from 10–15 mg of RV with the Qiagen RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Valencia, CA). Total RNA was recovered with A260/280 nm ranging from 1.85 to 2.10. Nine hundred nanograms of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Foster City, CA). Real-time RT-PCR was performed with TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). TaqMan assay primers included the following: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) (Ppargc1; Rn00580241_m1), estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) (Esr1; Rn01640372_m1), estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), (Esr2; Rn00562610_m1), G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPR30) (Gper1; Rn00592091_s1), and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Hprt1; Rn01527840_m1). Ten nanograms of cDNA was used to measure PGC-1α mRNA expression whereas 50 ng was used to measure Esr1, Esr2, and Gper1 on the Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR System. Changes in mRNA expression were determined by the comparative threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method (37). Data were normalized to Hprt1 and expressed as fold change compared with the intact female Sham group.

Electron Microscopy and Mitochondrial Ultrastructure Image Analysis

A section of the RV was immersed in cold Karnovsky fixative (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and processed for transmission electron microscopy to assess mitochondrial ultrastructure (21). For each rat RV, at least four images were acquired and analyzed with ImageJ. Mitochondrial content was reported as the average numbers of mitochondria counted per animal. Mitochondrial size was reported as the average cross-sectional area of contoured mitochondria per animal. These analyses were performed by a blinded observer.

Statistical Analysis

All values are presented as means ± standard error, stratified by exposure group and sex. Two-factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine differences in hemodynamic, biochemical, and histological outcome parameters due to PAB (Sham vs. PAB), sex (intact male vs. intact female or OVX female), and female sex hormone depletion (intact female vs. OVX female). Normal probability plots were examined to evaluate the normality assumption. If there was indication for unequal variances and/or violation of normality for an outcome variable, then the outcome variable was log-transformed before the formal comparisons were conducted. The Levene test for equal variances and standard model diagnostic procedure were then used to validate the model assumption after the log-transformation. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) method was utilized to control the type I error when conducting multiple pairwise comparisons between group/sex combinations.

To evaluate the statistical significance of differences in mechanoenergetic cost with PAB, sex, and female ovariectomy, a 2 × 3 factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted. In the initial analysis, iEa and iEes (or Ea and Ees) were included as two-dimensional dependent variables and the main and interaction effects of PAB, sex, and OVX as independent variables. Pairwise comparisons between the 2 × 3 factorial interaction effects were conducted using Tukey’s HSD method to control the type I error to be <0.05. To expand on this two-dimensional analysis, we performed another MANOVA with iEa, iEes, and [or Ea, Ees, and ] as three-dimensional dependent variables and PAB, sex, and OVX as independent variables. All reported P values are two sided. Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

17β-Estradiol Levels, Body Weights, and Growth

Ovariectomy in females did not alter bone growth, as tibia length was comparable between intact and OVX females (Table 1). Male rats were initially and terminally heavier than female rats regardless of ovariectomy or PAB, and OVX females weighed more than intact female rats at both time points. Over the course of 8 wk, all rats gained weight, with male rats gaining more than female rats. Serum 17β-estradiol levels in males, intact females, and OVX females were within physiological ranges as previously reported (9).

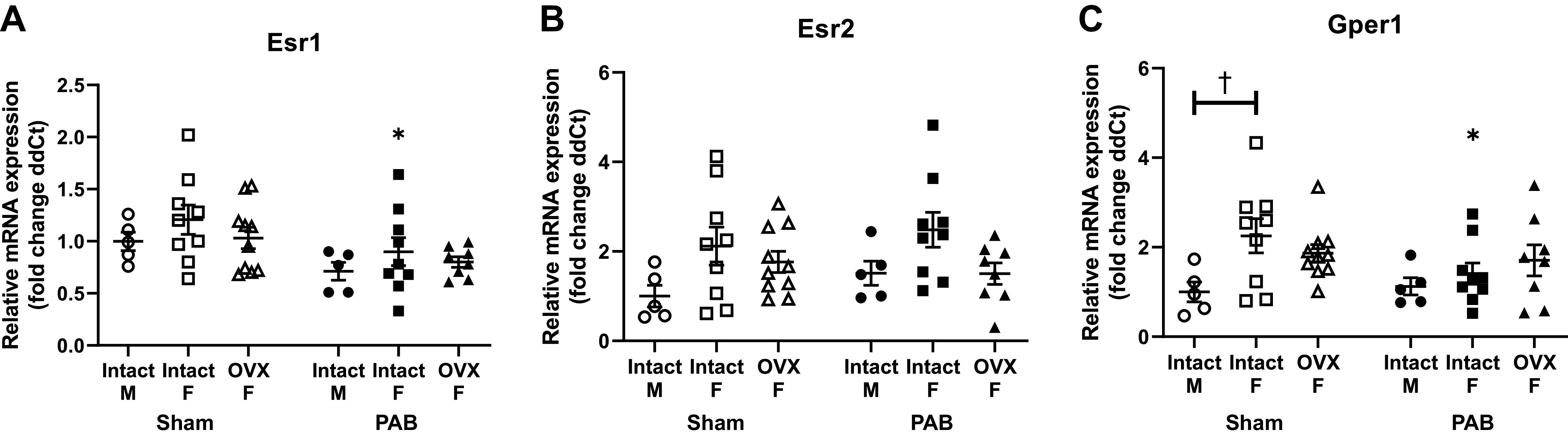

RV Estrogen Receptor Expression

The protective role of estrogen receptors in PAH and pressure-overloaded rodent models (9, 38, 39) motivated us to investigate whether transcript levels encoding ERα, ERβ, and Gper1 were sex or OVX dependent in the pressure-overloaded RV. Only intact female rats demonstrated a decrease in Esr1 and Gper1 gene expression in response to PAB (Fig. 2, A and C); no significant sex differences were found for Esr1, Esr2, and Gper1 transcript levels in response to PAB (Fig. 2). We observed that intact female Sham rats had greater Gper1 gene expression levels compared with male Sham rats. Sex- and OVX-dependent differences in these estrogen receptors therefore are unlikely contributors to sex- or OVX-dependent differences in RV structural or functional responses to PAB.

Figure 2.

Esr1, Esr2, and Gper1 transcript levels (fold change in delta cycle threshold values, or ddCT) in response to pulmonary artery banding (PAB) are not significantly dependent on sex or ovariectomy (OVX). Effects of sex and OVX on Esr1 [gene encoding for estrogen receptor (ER)α; A], Esr2 (gene encoding for ERβ; B), and Gper1 (C) are shown. n = 8–10 animals per group. Values are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham and †female (intact or OVX) vs. male (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference multiple comparison correction).

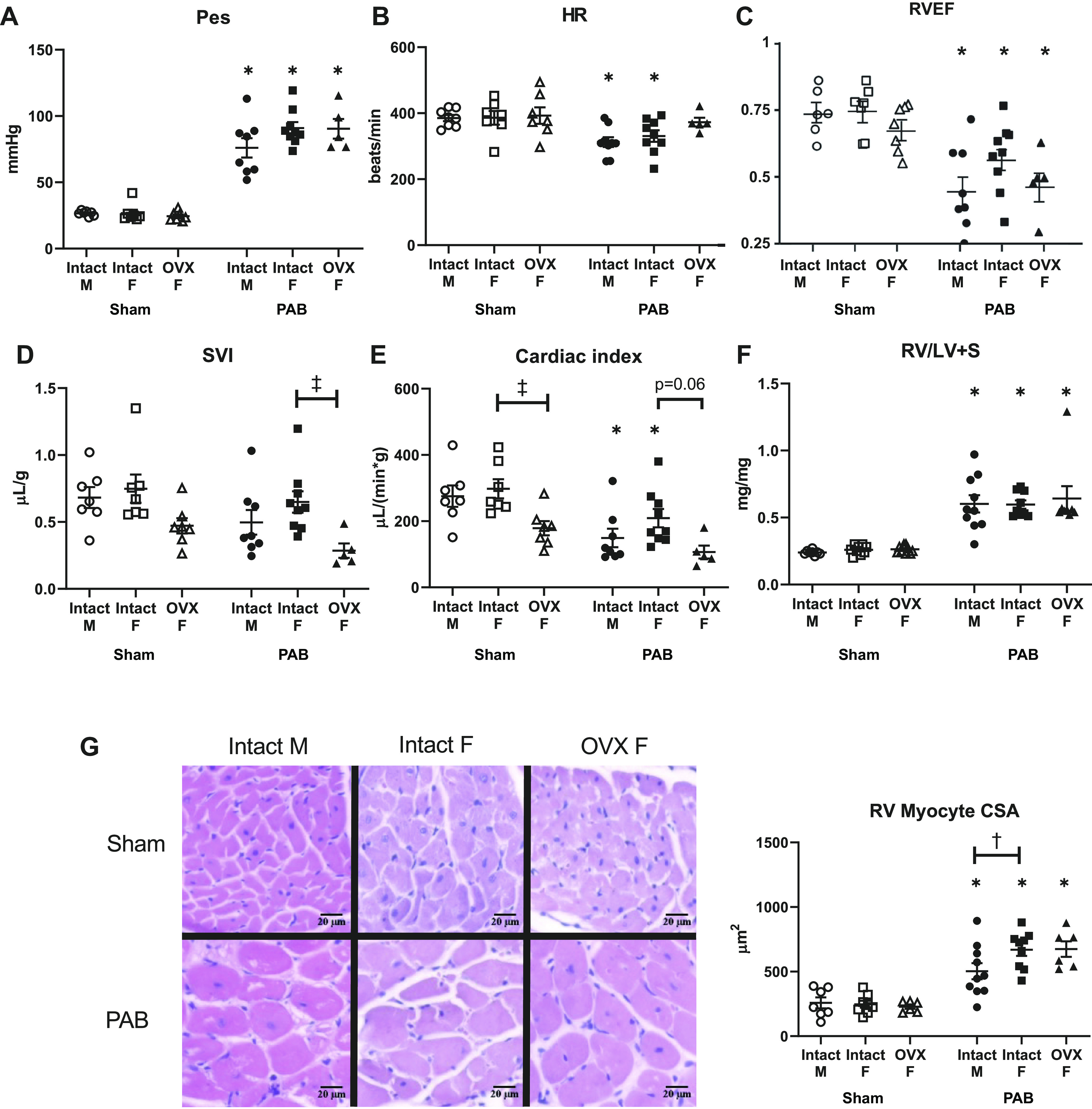

RV Hemodynamics, Systemic Hemodynamics, and RV Hypertrophy

Consistent with the experimental design, PAB generated comparable increases in RV Pes regardless of sex or ovariectomy (Fig. 3A). Heart rate but not SVI decreased after PAB in the intact animals (Fig. 3, B and D). RV ejection fraction (RVEF) was reduced in both the intact and OVX groups (Fig. 3C). Reduced heart rate was a partial contributor to decreased CI (Fig. 3E). In OVX animals, no difference in CI was observed between the Sham and PAB groups despite the decrease in SVI with PAB (Fig. 3, D and E). RV hypertrophy was observed in all PAB rats (Fig. 3F), with larger cardiomyocytes in intact females compared with males (Fig. 3G). Systemic pressures measured during open-chest right heart catheterization were not different in any group (Table 2). Overall, these findings demonstrate some sex-dependent (larger cardiomyocytes) and some OVX-dependent (smaller CI and SVI) RV structural and functional differences in response to PAB.

Figure 3.

Systolic adaptation to pulmonary artery banding (PAB) is independent of sex but dependent on ovariectomy (OVX). Effects of sex and OVX on right ventricle (RV) end-systolic pressure (Pes; A), heart rate (HR; B), RV ejection fraction (RVEF; C), stroke volume normalized to body weight (SVI; D), cardiac output normalized to body weight (cardiac index; E), RV weight scaled to left ventricular and septal weights (RV/LV+S; F), and RV myocyte cross-sectional area (CSA; G) are shown. G, left: representative images depict hematoxylin and eosin-stained RV tissue in male and female Sham and PAB rats (hematoxylin staining nuclei in blue, eosin staining cytoplasm in pink). Note that OVX reduced cardiac index in Sham rats. n = 8–10 animals per group. Values are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham, †female (intact or OVX) vs. male, and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference multiple comparison correction).

Table 2.

Hemodynamic parameters in Sham and pulmonary artery-banded rats

| Hemodynamics | Sham |

PAB |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact male | Intact female | OVX female | Intact male | Intact female | OVX female | |

| Peak systemic pressure, mmHg | 110 ± 5 | 116 ± 5 | 111 ± 8 | 122 ± 8 | 119 ± 5 | 115 ± 8 |

| RV end-diastolic pressure, mmHg | 4.50 ± 0.72 | 3.65 ± 0.38 | 3.00 ± 0.44 | 6.48 ± 0.71 | 6.46 ± 1.28* | 4.46 ± 0.84 |

| RV end-systolic volume index, μL/g | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.04* | 0.49 ± 0.09* | 0.32 ± 0.07 |

| RV end-diastolic volume index, μL/g | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 0.99 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.09 | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 1.14 ± 0.11 | 0.61 ± 0.08†‡ |

Values are presented as means ± SE. PAB, pulmonary artery banding; RV, right ventricle; Sham, sham surgery. n = 8–10 animals per group. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham, †female [intact or ovariectomized (OVX)] vs. male, and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference multiple comparison correction).

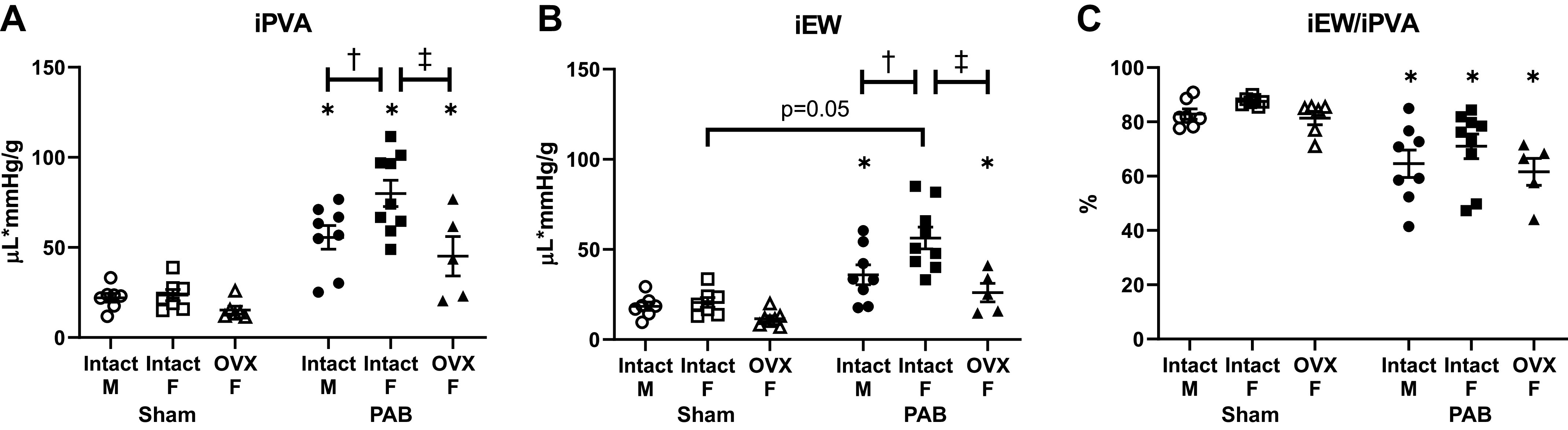

RV Hemodynamic Energy Input and Output Increase with PAB, with the Greatest Increases in Intact Females; Mechanical Efficiency Is Comparably Increased in All PAB Groups

We then investigated the effect of sex and ovariectomy on RV hemodynamic energetics with PAB. Energy input, measured by the total (potential plus stroke work) energy generated during contraction (iPVA), was increased in all PAB rats (Fig. 4A). Energy output, measured by energy used during contraction (iEW), also increased in all PAB rats, with the exception that in intact females this increase did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Intact females demonstrated greater increases in both iPVA and iEW compared with males; however, no significant difference was observed with loss of endogenous female sex hormones. As a consequence, the ratio of iPVA to iEW, which is the efficiency of mechanical energy used during contraction, was comparably decreased in all PAB rats, regardless of sex or ovariectomy (Fig. 4C). Thus, although sex and endogenous female sex hormones modulate increases in energy input and output with PAB, mechanical efficiency was not significantly changed.

Figure 4.

Increases in hemodynamic energy input in response to pulmonary artery banding (PAB) depend on sex and ovariectomy (OVX), but their ratio (mechanical efficiency) does not. Effects of sex and OVX for pressure-volume area scaled to body weight (iPVA; A), external work scaled to body weight (iEW; B), and mechanical efficiency (iEW/iPVA; C) are shown. n = 8–10 animals per group. Values are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham, †female (intact or OVX) vs. male, and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference multiple comparison correction).

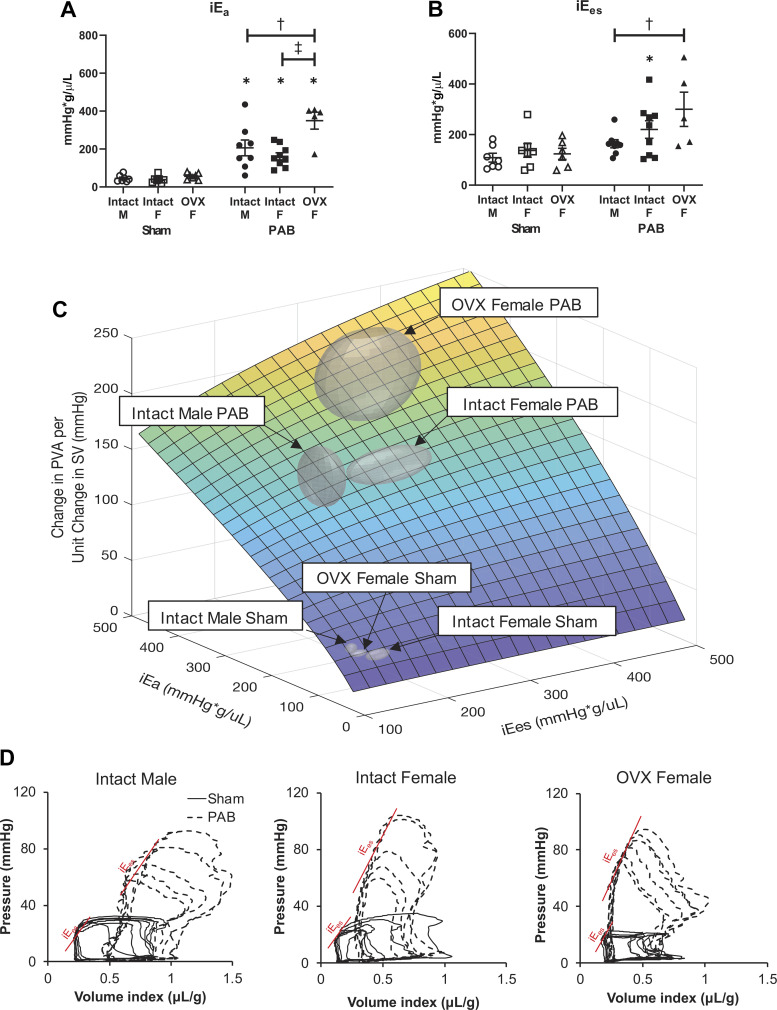

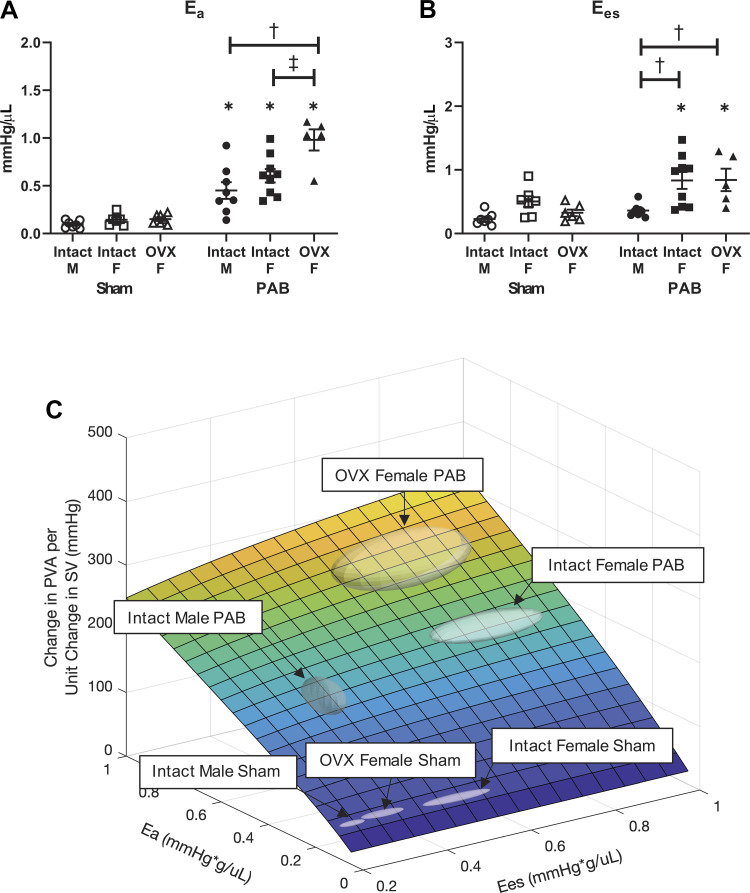

Effective Arterial Elastance and End-Systolic Elastance Increase with PAB Dependent on Sex or Ovariectomy; RV Mechanoenergetic Cost to Pump Blood Is Comparably Increased in All PAB Groups

Like hemodynamic energy input and output and mechanical efficiency, effective arterial elastance (iEa) and end-systolic elastance (iEes) increased with PAB in females (intact and OVX), and the mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood did not (Fig. 5). However, in males, although iEa increased with PAB, iEes did not (Fig. 5B). Also, unlike hemodynamic energy input, iEa had the greatest increase in the OVX females (Fig. 5A), and iEes increased more in OVX females than in intact females on average but the change was not significant because of high variability (Fig. 5B). Since iEa and iEes are independent variables in the calculated RV mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood, we performed a 3-D analysis (Fig. 5C) and used MANOVA to determine that RV mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood was increased in all PAB rats (P < 0.05) but did not significantly change based on sex or ovariectomy. Representative pressure-volume curves for each group are provided in Fig. 5D.

Figure 5.

Increases in indexed right ventricle (RV) contractility in response to pulmonary artery banding (PAB) depend on sex and ovariectomy (OVX), but mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood does not. A and B: effects of sex and OVX on indexed arterial elastance (iEa; A) and indexed end-systolic elastance (iEes; B) are shown for each group. n = 8–10 animals per group. Values are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham, †female (intact or OVX) vs. male, and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) multiple comparison correction). C: model-based estimation of RV mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood [change in pressure-volume area (PVA) per unit change in stroke volume (SV)] as a function of iEa and iEes. The group centroid is located at the group average (iEa, iEes); the boundary is defined by the SE. PAB groups are significantly different from Sham (P < 0.05) by multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. D: representative pressure-volume loops recorded during transient vena cava occlusion, from which iEa and iEes are calculated for each group.

We also confirmed that the results of this analysis do not depend on normalizing Ea, Ees, and mechanoenergetic cost to deliver blood to body weight (Fig. 6). When these parameters are not normalized, Ea was increased in all PAB rats, with the greatest increase in the OVX females (Fig. 6A), and Ees was increased significantly in intact and OVX females (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Increases in (nonindexed) right ventricle (RV) contractility in response to pulmonary artery banding (PAB) depend on sex and ovariectomy (OVX), but mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood does not. A and B: effects of sex and OVX on arterial elastance (Ea; A) and end-systolic elastance (Ees; B) are shown for each group. n = 8–10 animals per group. Values are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham, †female (intact or OVX) vs. male, and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) multiple comparison correction). C: model-based estimation of RV mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood [change in pressure-volume area (PVA) per unit change in stroke volume (SV)] as a function of Ea and Ees. The group centroid is located at the group average (Ea, Ees); the boundary is defined by the SE. PAB groups are significantly different from Sham (P < 0.05) by multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test.

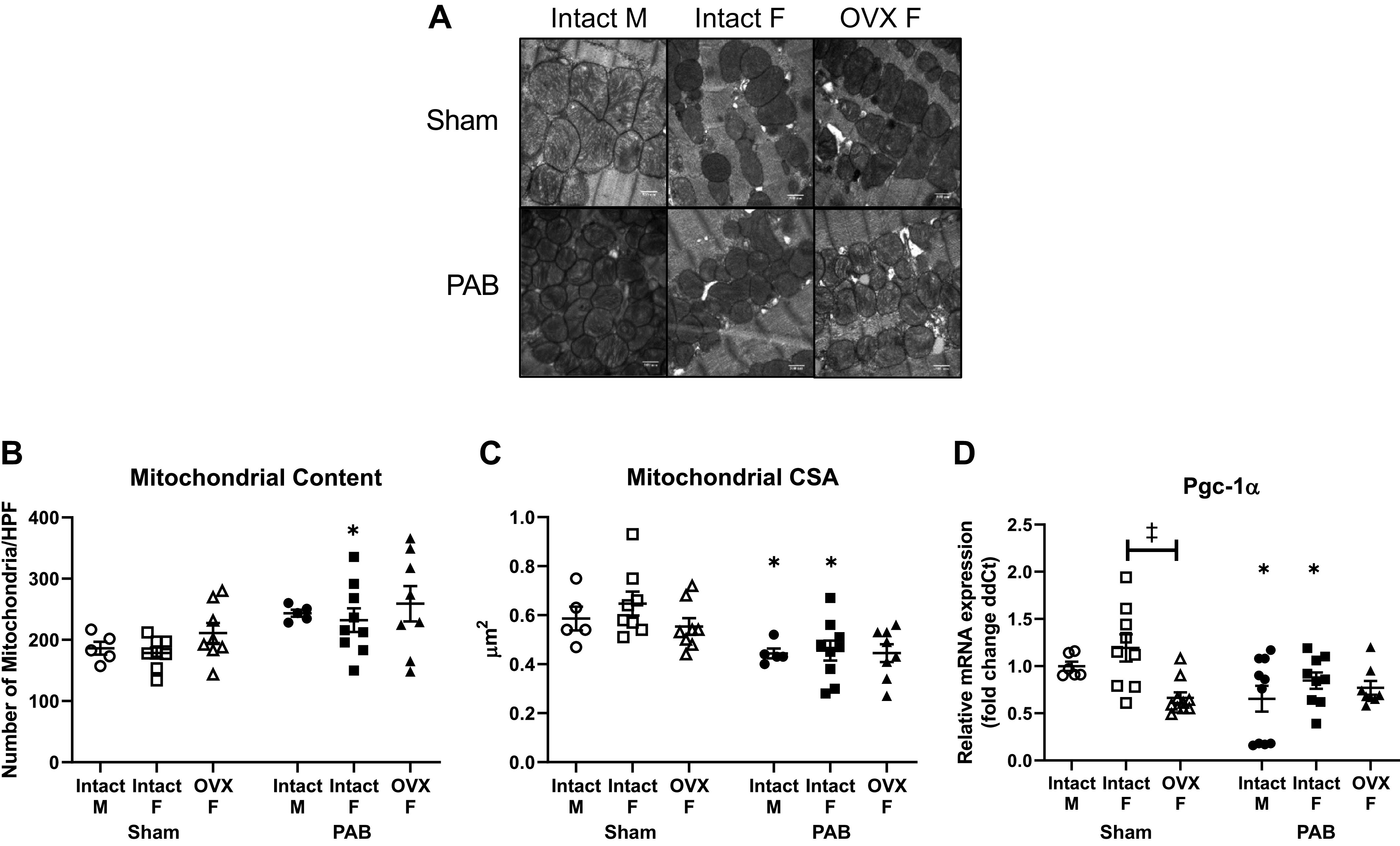

RV Mitochondrial Ultrastructure and PGC-1α Transcription Levels in Response to PAB Are Not Dependent on Sex or Ovariectomy

We next investigated whether the impact of sex and ovariectomy on energy input was mediated by mitochondrial ultrastructure. RV tissue from intact females demonstrated increased number of mitochondria that corresponded with comparable decrease in mitochondrial size (Fig. 7, B and C). Interestingly, male rats also exhibited a significant decrease in mitochondrial size with no significant change in mitochondrial content. As mitochondrial structural remodeling is regulated by PGC-1α (40), we evaluated for sex differences in PGC-1α transcription levels and found that intact female and male rats had comparable downregulation of PGC-1α with PAB (Fig. 7D). Although ovariectomy alone reduced PGC-1α transcription level in Sham rats, mitochondrial number and size were not significantly altered (Fig. 7, B–D). Furthermore, in response to PAB, mitochondrial number, mitochondrial size, and PGC-1α transcription level in OVX PAB rats were not different from OVX Sham rats or intact female PAB rats (Fig. 7, B–D). Taken together, mitochondrial ultrastructure and PGC-1α transcription levels in response to PAB were largely independent of sex and female sex hormone depletion and did not correspond with changes seen in hemodynamic energy input or RV systolic function.

Figure 7.

Right ventricular (RV) mitochondrial remodeling in response to pulmonary artery banding (PAB) is dependent on sex and ovariectomy (OVX). B–D: effects of sex and OVX on mitochondrial content (B), mitochondrial size (C), and gene expression (fold change in delta cycle threshold values, or ddCT) of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α; D) are shown. A: representative electron micrographs captured at ×25,000 magnification are shown for each group. Number of mitochondria was calculated as the counted number of mitochondria per high-power field (HPF). Mitochondrial size was calculated as the cross-sectional area (CSA) of mitochondria per HPF. Note the significant decrease in PGC-1α expression in OVX Sham rats. n = 8–10 animals per group. Values are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference multiple comparison correction).

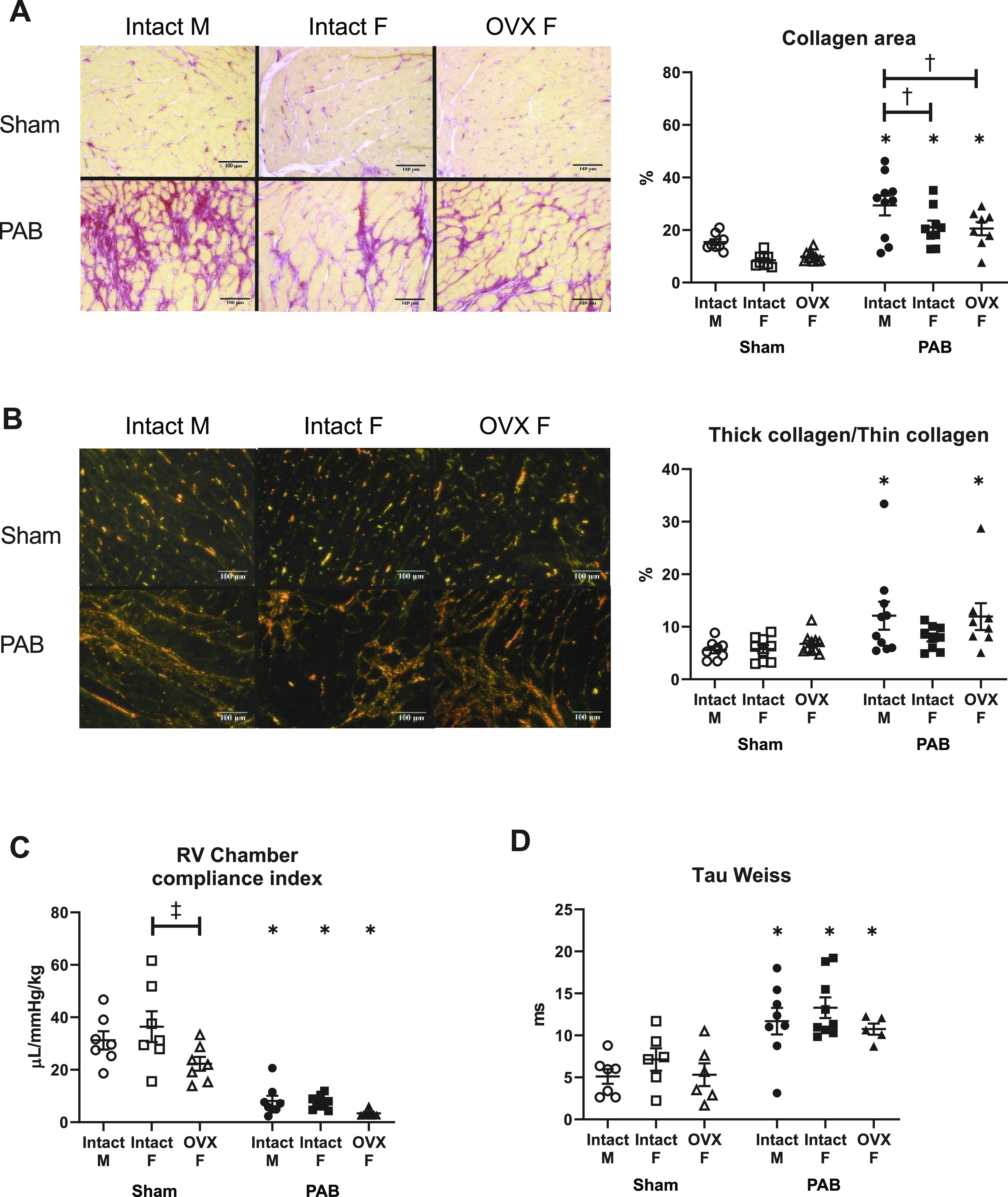

RV Collagen Content and Collagen Organization Are Affected by Sex and Ovariectomy; RV Diastolic Function Is Comparably Impaired in All PAB Groups

Since collagen accumulation can impair diastolic function (15), we investigated sex differences in 1) interstitial collagen content and 2) the ratio of thick collagen fibers, which contribute to material stiffness, to thin collagen fibers, which contribute to compliance (41). Although RV collagen content was increased in all PAB rats, the increase was significantly smaller in female rats independent of ovariectomy (Fig. 8A). In male and ovariectomized female rats with PAB, the increased ratio of thick to thin collagen indicated more packing of collagen fibers into thick collagen bundles (Fig. 8B). In contrast, intact female rats with PAB had a preserved ratio, suggesting that more thin collagen bundles accumulated. These results indicate that in response to PAB sex impacts the degree of collagen deposition and that loss of endogenous female sex hormones impacts the organization of collagen fibers.

Figure 8.

Increases of collagen content and changes in organization in response to pulmonary artery banding (PAB) depend on sex and ovariectomy (OVX), but diastolic function does not. Effects of sex and OVX are shown for right ventricle (RV) interstitial collagen area (A), RV collagen organization into thick-to-thin collagen fibers (B), RV chamber compliance indexed to body weight (C), and tau Weiss (D). Representative images under brightfield (A) and polarized (B) light were captured at ×20 magnification. Collagen was stained with Picrosirius red; collagen area was calculated as the ratio of the area positive for collagen (stained in pink and red) to the total tissue area (stained yellow). Thick, tightly packed collagen and thin, loosely aligned collagen were identified as different interference colors under polarized light, with thick collagen defined as areas of yellow, orange, or red color and thin collagen defined as areas of green color. Note that OVX reduced RV chamber compliance index in Sham rats. n = 8–10 animals per group. Values are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 for *PAB vs. respective Sham, †female (intact or OVX) vs. male, and ‡OVX vs. intact female (2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference multiple comparison correction).

Interestingly, these differences in collagen organization were not demonstrated to be associated with diastolic dysfunction. Regardless of sex or ovariectomy, all PAB rats demonstrated comparable RV chamber stiffening (reduced chamber compliance) and prolonged active relaxation (increased tau Weiss) (Fig. 8, C and D). RV myocardial stiffening was also evident in OVX Sham animals.

DISCUSSION

Our major findings are that, in rats challenged with RV pressure overload via PAB, 1) mechanical efficiency decreased and mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood increased independently of sex, despite differences in hemodynamic energy input, output, and contractility, and 2) diastolic dysfunction occurred independently of sex, despite differences in collagen content and organization. Loss of endogenous sex hormones modulated some of these changes. These data suggest that even though sex and female endogenous sex hormones modulate RV contractile responses and energy input and output responses, the mechanoenergetic cost for the RV to pump blood is not affected by sex or sex hormones. In other words, even though the individual components contributing to RV mechanoenergetic cost are differentially affected by sex and sex hormones in our model, the “end product” of RV mechanoenergetic cost is constant across sexes and after ovariectomy, suggesting a homeostatic target to which the system returns when perturbed. In this case, the target would be maintained mechanoenergetic cost or efficiency.

In disease states characterized by RV pressure overload, women have superior RV systolic function (2–6). Preclinical studies in rodent models of PH have recapitulated these clinical findings (9, 10). However, since female sex can alleviate PH-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling (9, 10), sex-dependent changes in RV afterload confound study of the impact of female sex on RV function. Using PAB to induce comparable pressure overload in male and female rats, we confirmed that female rats have greater generation and utilization of mechanical energy (iPVA and iEW) and greater RV contractility (iEes), i.e., improved RV systolic adaptation, compared with male rats. These results are consistent with greater RV contractility found in female PAH patients compared with male PAH patients (5). Interestingly, despite these differences overall mechanoenergetic function, quantified by both mechanical efficiency and mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood, was not statistically different between the sexes. Although no conclusions can be drawn from the nonsignificant data shown here, this finding may suggest a sex-independent mechanoenergetic efficiency target that RV systolic adaptation maintains during pressure overload despite mechanoenergetic remodeling pathways that are sex dependent. It is unknown, however, whether the sexes can maintain this mechanoenergetic efficiency for a similar duration. Since male PAH patients have inferior RV adaptation and higher mortality compared with their female counterparts, they may “fall off the cliff” sooner. This may be representative of an intermediate stage of RV adaptation for male rats, implying that there may be some male compensatory response to lower the energetic cost to pump blood that is not observed in the intact female rats and may not be sustainable long term. This idea becomes more intriguing when taken together with the fact that SV and iEes were lower in males compared with intact and OVX females, suggesting a possible sex-dependent compensatory mechanism (or lack thereof) related to RV contractility. However, dedicated time course studies, including an intermediate state of adaptation in males as well as overt RV failure in both males and females, are required to test this hypothesis. To test the hypothesis of a mechanoenergetic efficiency homeostatic set point, one could disrupt cardiomyocyte energetics (e.g., mitochondrial energy generation) constitutively and then observe whether mechanoenergetic efficiency was still maintained at baseline and with pressure overload.

We further explored sex differences by studying the effect of female sex hormone depletion. Menopause is a risk factor for PAH development in patients with scleroderma (42), and more favorable hemodynamics in PAH are seen in women <45 yr old (7), which suggest that loss of female sex hormones (e.g., menopause) impairs RV systolic adaptation to PH. Moreover, estrogen therapy has been shown to contribute to improved RV function in ovariectomized rodents with PH (9, 10, 26). Here we found that loss of endogenous sex hormones limited the increase in generation and utilization of mechanical energy during contraction with no significant effect on RV contractility. Again, despite these differences, mechanical efficiency was not altered by loss of endogenous sex hormones. Although not significant, the mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood was higher in the OVX group. Since the OVX PAB group had the most anesthesia-related death, loss of data from these sickest animals may have artifactually decreased mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood, which warrants further investigation.

To discover the underlying mechanisms contributing to superior female energy generation and contractility in response to pressure overload, we measured mitochondrial ultrastructure and PGC-1α transcription levels with PAB. Although sex differences in mitochondrial ultrastructure and PGC-1α expression level in healthy left ventricle (LV) have been reported (43, 44), we found no differences between Sham males and females. We also did not find differences in mitochondrial number or size between Sham males and females, consistent with prior data showing that mitochondrial oxidative capacity is independent of sex (44–47). In response to pressure overload in intact males and females, mitochondrial number increased, mitochondrial size decreased, and PGC-1α transcription decreased, demonstrating sex independence. These changes were generally lost with ovariectomy, suggesting some dependence on endogenous female sex hormones. The regulation of mitochondrial function and energetics is a complex process involving multiple regulators (48, 49), and regulators that were not studied here may be altered. Future studies investigating additional regulators and dissecting time courses are needed. Importantly, these changes in mitochondrial function and energetics do not explain sex-dependent differences in hemodynamic energy input, output, and contractility.

In the pressure-overloaded LV, sex differences in diastolic dysfunction have been linked with increased rate of collagen deposition (50). Greater ratio of thick to thin collagen fibers and hypertrophy both appear to contribute to myocardial stiffening and diastolic dysfunction in both pressure-overloaded ventricles (14, 15, 41). However, sex differences in these features and their resulting contribution to diastolic dysfunction have not yet been investigated. Here, we demonstrate sex differences in collagen content and organization with PAB that nevertheless do not cause sex differences in diastolic stiffening or dysfunction. Males showed more collagen content and higher thick-to-thin collagen ratio, whereas females had a smaller increase in collagen content with no change in thick-to-thin collagen ratio. Interestingly, OVX females had collagen content comparable to intact females with a greater thick-to-thin collagen ratio. Despite these differences in structure, diastolic function was comparably impaired in all groups with pressure overload. Thus, similar to mechanoenergetic remodeling and systolic function, these results suggest a sex-independent homeostatic set point that governs RV diastolic adaptation to pressure overload achieved via remodeling mechanisms that are sex dependent.

Study Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, measurements were made at only one time point following a specific degree of PAB such that causal relationships and the relative timing of structural and functional changes in each sex could not be determined. Time courses and different degrees of PAB may result in differential RV energetic responses. It should also be noted that we did not track changes in the pressure gradient across the banded region to ensure consistent levels of banding. However, calculation of pulmonary vascular resistance (Pes/CI) showed comparable amounts of RV afterload with banding across all groups. Second, other factors influenced by sex and loss of endogenous female sex hormones that were not accounted for in this study include oxidative stress (23, 43), calcium handling (51–54), and inflammation (55). Third, although mitochondrial structure and PGC-1α are strongly linked with mitochondrial function (40, 56), mitochondrial function was not assessed in this study. Fourth, the model-based prediction of cardiac energy cost to deliver blood does not account for some important physiological factors such as heart rate and sympathetic stimulation that are altered with disease progression. Revision of the modeling approach could enhance its ability to predict ventricular function changes in response to pathological stimuli. Fifth, there was a notable difference in body weight between the intact female and OVX groups at baseline, despite being inbred, from the same vendor, and of the same approximate age, which may confound the comparison between these groups. Finally, the experiments in male rats were conducted 2 yr earlier than those in intact and OVX female rats and by different surgeons. Although care and handling of animals, surgical techniques, instrumentation, and data analyses were otherwise identical, comparisons between sexes need to be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, with the present study we demonstrate that increases in RV hemodynamic energy generation (input), energy utilization (output), and contractility are greater in females than males, whereas mechanical efficiency and mechanoenergetic cost to pump blood are not. Similarly, increases in collagen content and changes in collagen organization are sex dependent, whereas diastolic dysfunction is not. These results point toward sex-dependent mechanisms of remodeling that may be achieved via sex-independent mechanoenergetics and diastolic function, which warrants further investigation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the NIH (grant numbers 1R56HL134736-01A1 to T. Lahm, R01-HL144727-01A1 to T. Lahm, R01-HL-086939 and R01-HL-154624 to N. C. Chesler, T32-HL-007936 to T.-C. Cheng) and a VA Merit Review Award (grant number 2 I01 BX002042 to T. Lahm).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.-C.C., D.M.T., and N.C.C. conceived and designed research; T.-C.C. and T.A.H. performed experiments; T.-C.C., L.C., T.A.H., J.C.E., T.L., and N.C.C. analyzed data; T.-C.C., L.C., A.L.F., T.A.H., T.L., and N.C.C. interpreted results of experiments; T.-C.C. and L.C. prepared figures; T.-C.C. and N.C.C. drafted manuscript; D.M.T., L.C., A.L.F., T.L., and N.C.C. edited and revised manuscript; T.-C.C., D.M.T., L.C., A.L.F., T.A.H., J.C.E., T.L., and N.C.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Peiqing Wang, Allison Rodgers, and Randy Massey for technical expertise and valuable help with the surgery, echocardiography, and electron microscopy, respectively. We are grateful to Abigail Drake and Tony So for help with data collection and analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hester J, Ventetuolo C, Lahm T. Sex, gender, and sex hormones in pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular failure. Compr Physiol 10: 125–170, 2019. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c190011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foppa M, Arora G, Gona P, Ashrafi A, Salton CJ, Yeon SB, Blease SJ, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Manning WJ, Chuang ML. Right ventricular volumes and systolic function by cardiac magnetic resonance and the impact of sex, age, and obesity in a longitudinally followed cohort free of pulmonary and cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 9: e003810, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs W, van de Veerdonk MC, Trip P, de Man F, Heymans MW, Marcus JT, Kawut SM, Bogaard HJ, Boonstra A, Vonk Noordegraaf A. The right ventricle explains sex differences in survival in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 145: 1230–1236, 2014. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shigeta A, Tanabe N, Shimizu H, Hoshino S, Maruoka M, Sakao S, Tada Y, Kasahara Y, Takiguchi Y, Tatsumi K, Masuda M, Kuriyama T. Gender differences in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in Japan. Circ J 72: 2069–2074, 2008. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tello K, Richter MJ, Yogeswaran A, Ghofrani HA, Naeije R, Vanderpool R, Gall H, Tedford RJ, Seeger W, Lahm T. Sex differences in right ventricular-pulmonary arterial coupling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 202: 1042–1046, 2020. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0807LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventetuolo CE, Ouyang P, Bluemke DA, Tandri H, Barr RG, Bagiella E, Cappola AR, Bristow MR, Johnson C, Kronmal RA, Kizer JR, Lima JA, Kawut SM. Sex hormones are associated with right ventricular structure and function: the MESA-right ventricle study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 659–667, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1027OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ventetuolo CE, Praestgaard A, Palevsky HI, Klinger JR, Halpern SD, Kawut SM. Sex and haemodynamics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 43: 523–530, 2014. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00027613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Patel JR, Schreier DA, Hacker TA, Moss RL, Chesler NC. Organ-level right ventricular dysfunction with preserved Frank-Starling mechanism in a mouse model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Appl Physiol (1985) 124: 1244–1253, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00725.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frump AL, Goss KN, Vayl A, Albrecht M, Fisher A, Tursunova R, Fierst J, Whitson J, Cucci AR, Brown MB, Lahm T. Estradiol improves right ventricular function in rats with severe angioproliferative pulmonary hypertension: effects of endogenous and exogenous sex hormones. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L873–L890, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00006.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahm T, Frump AL, Albrecht ME, Fisher AJ, Cook TG, Jones TJ, Yakubov B, Whitson J, Fuchs RK, Liu A, Chesler NC, Brown MB. 17Beta-estradiol mediates superior adaptation of right ventricular function to acute strenuous exercise in female rats with severe pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 311: L375–L388, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00132.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asanoi H, Kameyama T, Ishizaka S, Nozawa T, Inoue H. Energetically optimal left ventricular pressure for the failing human heart. Circulation 93: 67–73, 1996. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson RC, Datar SA, Oishi PE, Bennett S, Maki J, Sun C, Johengen M, He Y, Raff GW, Redington AN, Fineman JR. Adaptive right ventricular performance in response to acutely increased afterload in a lamb model of congenital heart disease: evidence for enhanced Anrep effect. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H1222–H1230, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01018.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaguchi M, Hay I, Fetics B, Kass DA. Combined ventricular systolic and arterial stiffening in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: implications for systolic and diastolic reserve limitations. Circulation 107: 714–720, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000048123.22359.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendes-Ferreira P, Santos-Ribeiro D, Adão R, Maia-Rocha C, Mendes-Ferreira M, Sousa-Mendes C, Leite-Moreira AF, Brás-Silva C. Distinct right ventricle remodeling in response to pressure overload in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H85–H95, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00089.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rain S, Andersen S, Najafi A, Gammelgaard Schultz J, da Silva Gonçalves Bós D, Handoko ML, Bogaard HJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Andersen A, van der Velden J, Ottenheijm CA, de Man FS. Right ventricular myocardial stiffness in experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension: relative contribution of fibrosis and myofibril stiffness. Circ Heart Fail 9: e002636, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rain S, Handoko ML, Trip P, Gan CT, Westerhof N, Stienen GJ, Paulus WJ, Ottenheijm CA, Marcus JT, Dorfmüller P, Guignabert C, Humbert M, Macdonald P, Dos Remedios C, Postmus PE, Saripalli C, Hidalgo CG, Granzier HL, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, van der Velden J, de Man FS. Right ventricular diastolic impairment in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 128: 2016–2025, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naeije R, Brimioulle S, Dewachter L. Biomechanics of the right ventricle in health and disease (2013 Grover Conference series). Pulm Circ 4: 395–406, 2014. doi: 10.1086/677354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vega RB, Konhilas JP, Kelly DP, Leinwand LA. Molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac adaptation to exercise. Cell Metab 25: 1012–1026, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, Forfia PR, Kawut SM, Lumens J, Naeije R, Newman J, Oudiz RJ, Provencher S, Torbicki A, Voelkel NF, Hassoun PM. Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 62: D22–D33, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suga H. Ventricular energetics. Physiol Rev 70: 247–277, 1990. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng TC, Philip JL, Tabima DM, Hacker TA, Chesler NC. Multiscale structure-function relationships in right ventricular failure due to pressure overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H699–H708, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00047.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schipke JD. Cardiac efficiency. Basic Res Cardiol 89: 207–240, 1994. doi: 10.1007/BF00795615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavón N, Cabrera-Orefice A, Gallardo-Pérez JC, Uribe-Alvarez C, Rivero-Segura NA, Vazquez-Martínez ER, Cerbón M, Martínez-Abundis E, Torres-Narvaez JC, Martínez-Memije R, Roldán-Gómez FJ, Uribe-Carvajal S. In female rat heart mitochondria, oophorectomy results in loss of oxidative phosphorylation. J Endocrinol 232: 221–235, 2017. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuwabara M, Maruyama H, Onitsuka T, Koga Y. Myocardial energetics and cardiac function of preserved rat heart. Jpn Circ J 56: 710–715, 1992. doi: 10.1253/jcj.56.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suga H, Hayashi T, Shirahata M. Ventricular systolic pressure-volume area as predictor of cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol 240: H39–H44, 1981. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.1.H39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu A, Schreier D, Tian L, Eickhoff JC, Wang Z, Hacker TA, Chesler NC. Direct and indirect protection of right ventricular function by estrogen in an experimental model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H273–H283, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00758.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgdorff MA, Koop AM, Bloks VW, Dickinson MG, Steendijk P, Sillje HH, van Wiechen MP, Berger RM, Bartelds B. Clinical symptoms of right ventricular failure in experimental chronic pressure load are associated with progressive diastolic dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 79: 244–253, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sagawa K. Cardiac Contraction and the Pressure-Volume Relationship. New York: Oxford University Press USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kass DA, Kelly RP. Ventriculo-arterial coupling: concepts, assumptions, and applications. Ann Biomed Eng 20: 41–62, 1992. doi: 10.1007/BF02368505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, Kass DA. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation 86: 513–521, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suga H, Hayashi T, Suehiro S, Hisano R, Shirahata M, Ninomiya I. Equal oxygen consumption rates of isovolumic and ejecting contractions with equal systolic pressure-volume areas in canine left ventricle. Circ Res 49: 1082–1091, 1981. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suga H, Igarashi Y, Yamada O, Goto Y. Mechanical efficiency of the left ventricle as a function of preload, afterload, and contractility. Heart Vessels 1: 3–8, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF02066480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nozawa T, Yasumura Y, Futaki S, Tanaka N, Uenishi M, Suga H. Efficiency of energy transfer from pressure-volume area to external mechanical work increases with contractile state and decreases with afterload in the left ventricle of the anesthetized closed-chest dog. Circulation 77: 1116–1124, 1988. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.5.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betz P, Nerlich A, Wilske J, Wiest I, Penning R, Eisenmenger W. Comparison of the solophenyl-red polarization method and the immunohistochemical analysis for collagen type III. Int J Legal Med 105: 27–29, 1992. doi: 10.1007/BF01371233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Junqueira LC, Montes GS, Sanchez EM. The influence of tissue section thickness on the study of collagen by the Picrosirius-polarization method. Histochemistry 74: 153–156, 1982. doi: 10.1007/BF00495061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montes GS, Junqueira LC. The use of the Picrosirius-polarization method for the study of the biopathology of collagen. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 86, Suppl 3: 1–11, 1991. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761991000700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-Delta Delta CT method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iorga A, Li J, Sharma S, Umar S, Bopassa JC, Nadadur RD, Centala A, Ren S, Saito T, Toro L, Wang Y, Stefani E, Eghbali M. Rescue of pressure overload-induced heart failure by estrogen therapy. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e002482, 2016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iorga A, Umar S, Ruffenach G, Aryan L, Li J, Sharma S, Motayagheni N, Nadadur RD, Bopassa JC, Eghbali M. Estrogen rescues heart failure through estrogen receptor beta activation. Biol Sex Differ 9: 48, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s13293-018-0206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehman JJ, Boudina S, Banke NH, Sambandam N, Han X, Young DM, Leone TC, Gross RW, Lewandowski ED, Abel ED, Kelly DP. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha is essential for maximal and efficient cardiac mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and lipid homeostasis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H185–H196, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00081.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jalil JE, Doering CW, Janicki JS, Pick R, Shroff SG, Weber KT. Fibrillar collagen and myocardial stiffness in the intact hypertrophied rat left ventricle. Circ Res 64: 1041–1050, 1989. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scorza R, Caronni M, Bazzi S, Nador F, Beretta L, Antonioli R, Origgi L, Ponti A, Marchini M, Vanoli M. Post-menopause is the main risk factor for developing isolated pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 966: 238–246, 2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colom B, Oliver J, Roca P, Garcia-Palmer FJ. Caloric restriction and gender modulate cardiac muscle mitochondrial H2O2 production and oxidative damage. Cardiovasc Res 74: 456–465, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khalifa AR, Abdel-Rahman EA, Mahmoud AM, Ali MH, Noureldin M, Saber SH, Mohsen M, Ali SS. Sex-specific differences in mitochondria biogenesis, morphology, respiratory function, and ROS homeostasis in young mouse heart and brain. Physiol Rep 5: e13125, 2017. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barba I, Miró-Casas E, Torrecilla JL, Pladevall E, Tejedor S, Sebastián-Pérez R, Ruiz-Meana M, Berrendero JR, Cuevas A, García-Dorado D. High-fat diet induces metabolic changes and reduces oxidative stress in female mouse hearts. J Nutr Biochem 40: 187–193, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colom B, Oliver J, Garcia-Palmer FJ. Sexual dimorphism in the alterations of cardiac muscle mitochondrial bioenergetics associated to the ageing process. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70: 1360–1369, 2015. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanz A, Hiona A, Kujoth GC, Seo AY, Hofer T, Kouwenhoven E, Kalani R, Prolla TA, Barja G, Leeuwenburgh C. Evaluation of sex differences on mitochondrial bioenergetics and apoptosis in mice. Exp Gerontol 42: 173–182, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osellame LD, Blacker TS, Duchen MR. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial function. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 26: 711–723, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosca MG, Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Mitochondria in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 55: 31–41, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruppert M, Korkmaz-Icöz S, Loganathan S, Jiang W, Lehmann L, Oláh A, Sayour AA, Barta BA, Merkely B, Karck M, Radovits T, Szabó G. Pressure-volume analysis reveals characteristic sex-related differences in cardiac function in a rat model of aortic banding-induced myocardial hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H502–H511, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00202.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curl CL, Wendt IR, Kotsanas G. Effects of gender on intracellular [Ca2+] in rat cardiac myocytes. Pflugers Arch 441: 709–716, 2001. doi: 10.1007/s004240000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farrell SR, Ross JL, Howlett SE. Sex differences in mechanisms of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H36–H45, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00299.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwertz DW, Beck JM, Kowalski JM, Ross JD. Sex differences in the response of rat heart ventricle to calcium. Biol Res Nurs 5: 286–298, 2004. doi: 10.1177/1099800403262615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turdi S, Huff AF, Pang J, He EY, Chen X, Wang S, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Ren J. 17-Beta estradiol attenuates ovariectomy-induced changes in cardiomyocyte contractile function via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Toxicol Lett 232: 253–262, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nadadur RD, Umar S, Wong G, Eghbali M, Iorga A, Matori H, Partow-Navid R, Eghbali M. Reverse right ventricular structural and extracellular matrix remodeling by estrogen in severe pulmonary hypertension. J Appl Physiol (1985) 113: 149–158, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01349.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gomez-Arroyo J, Mizuno S, Szczepanek K, Van Tassell B, Natarajan R, dos Remedios CG, Drake JI, Farkas L, Kraskauskas D, Wijesinghe DS, Chalfant CE, Bigbee J, Abbate A, Lesnefsky EJ, Bogaard HJ, Voelkel NF. Metabolic gene remodeling and mitochondrial dysfunction in failing right ventricular hypertrophy secondary to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Heart Fail 6: 136–144, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.966127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]