Abstract

During the past two decades, the field of mammalian myocardial regeneration has grown dramatically, and with this expanded interest comes increasing claims of experimental manipulations that mediate bona fide proliferation of cardiomyocytes. Too often, however, insufficient evidence or improper controls are provided to support claims that cardiomyocytes have definitively proliferated, a process that should be strictly defined as the generation of two de novo functional cardiomyocytes from one original cardiomyocyte. Throughout the literature, one finds inconsistent levels of experimental rigor applied, and frequently the specific data supplied as evidence of cardiomyocyte proliferation simply indicate cell-cycle activation or DNA synthesis, which do not necessarily lead to the generation of new cardiomyocytes. In this review, we highlight potential problems and limitations faced when characterizing cardiomyocyte proliferation in the mammalian heart, and summarize tools and experimental standards, which should be used to support claims of proliferation-based remuscularization. In the end, definitive establishment of de novo cardiomyogenesis can be difficult to prove; therefore, rigorous experimental strategies should be used for such claims.

Keywords: cardiomyocyte, cytokinesis, heart regeneration, proliferation

INTRODUCTION

Historically, the cardiovascular field has argued that the adult mammalian myocardium is incapable of regenerating, largely attributed to the postmitotic nature of postnatal cardiomyocytes. Although fetal cardiac growth is largely hyperplastic in nature, driven by proliferation of the existing cardiomyocytes (1), the ability of cardiomyocytes to proliferate in large numbers after birth is compromised when hypertrophic growth is adopted. However, recent literature points to more complex, yet unambiguous truths: adult mammalian cardiomyocytes are replaced by new cardiomyocytes throughout the normal lifespan, albeit at a very low rate (2, 3); adult heart injury stimulates a response that includes cardiomyocyte proliferation, also at a low level (2); fetal and early neonatal heart injury is followed by a robust cardiomyocyte regenerative response (4, 5); and in all cases the source of new cardiomyocytes is thought to be primarily proliferation of pre-existing cardiomyocytes (2, 6). The question is, Can these insights, along with our understanding of heart development and with knowledge gained from experimentation on highly regenerative organs or animals, be harnessed to coax postmitotic cardiomyocytes to re-enter the cell cycle and divide? Over the past two decades, a steady stream of new studies have reported developments ranging from natural inter- and intraspecies variation in cardiomyocyte proliferative potential (7, 8) to genetic manipulations of potent signaling pathways capable of stimulating cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activation (9–17). Of course, other strategies to regenerate the heart have also been proposed, including reprogramming of fibrotic scar into contractile cardiomyocytes (18–20) and cell transplantation (21). However, for the sake of this review we will focus on endogenous cardiomyocyte proliferation.

With the influx of studies and strategies claiming to promote cardiomyocyte renewal in adult mammalian hearts, we find it pertinent to pause and discuss experimental standards used within our field. Definitively proving that an adult mammalian cardiomyocyte has completed cytokinesis to generate two new cardiomyocytes is a particularly daunting task, considering that the expression of cell-cycle markers (Table 1) does not necessarily translate to cell-cycle completion in this cell type (Fig. 1) (29). Here, we aim to summarize the approaches currently used for identifying and quantifying mammalian cardiomyocyte proliferation, highlight the limitations and advantages inherent in each method, and put forward experimental standards for the field of heart regeneration with four main topics discussed: 1) identifying cell-cycle activated cardiomyocyte nuclei, 2) distinguishing cell-cycle activation from proliferation, 3) assessing cardiomyocyte endowment, and 4) proper controls when using genetically engineered models. In addition, we discuss how these experimental standards may be different for large mammals, including porcine models, and when analyzing human heart disease.

Table 1.

Markers of cell-cycle progression

| Marker | Cell-Cycle Stage(s) | Localization | Notes and Limitations | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody and staining-based detection | ||||

| Ki67 | G1-S-G2-M | Nucleus | Cannot discriminate between division and endomitosis | |

| Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | S | Nucleus | Cannot discriminate between division and endomitosis | |

| Thymidine analogs | S | Nucleus | Cannot discriminate between division and endomitosis | |

| Can also get incorporated during DNA repair; not cell cycle | ||||

| phospho-Histone H3 | M | Nucleus | Cannot discriminate between division and endomitosis | |

| Aurora kinase B | M | Nucleus | Irregular positioning at cleavage furrow during endomitosis | (22, 23) |

| Cytokinesis | Cleavage furrow | Difficult to visualize irregularities in histological sections | ||

| Difficult to assign to cardiomyocytes in histological sections | ||||

| Anillin | G1-S-G2 | Nucleus | Irregular positioning at cleavage furrow during endomitosis | (22, 23) |

| M | Cell cortex | Difficult to visualize irregularities in histological sections | ||

| Cytokinesis | Cleavage furrow | Difficult to assign to cardiomyocytes in histological sections | ||

| Genetic alleles | ||||

| Fucci | G0, G1 | Nucleus (red) | Transgenic mouse requiring extra allele | (24) |

| S, G2, M | Nucleus (green) | Cannot visualize cytokinesis | ||

| Myh6-eGFP-Anillin | G1-S-G2 | Nucleus | GFP-Anillin fusion under the control of the Myh6 promoter | (23) |

| M | Cell cortex | Cardiomyocyte-specific expression | ||

| Cytokinesis | Cleavage furrow | Still relies on irregular positioning to assess true division | ||

| Ki67-recombinase | G1-S-G2-M | Cardiomyocyte specificity when subject to Myh6-driven activation. Used in “sparse labeling” logic to demonstrate division by appearance of doublets | (25, 26) | |

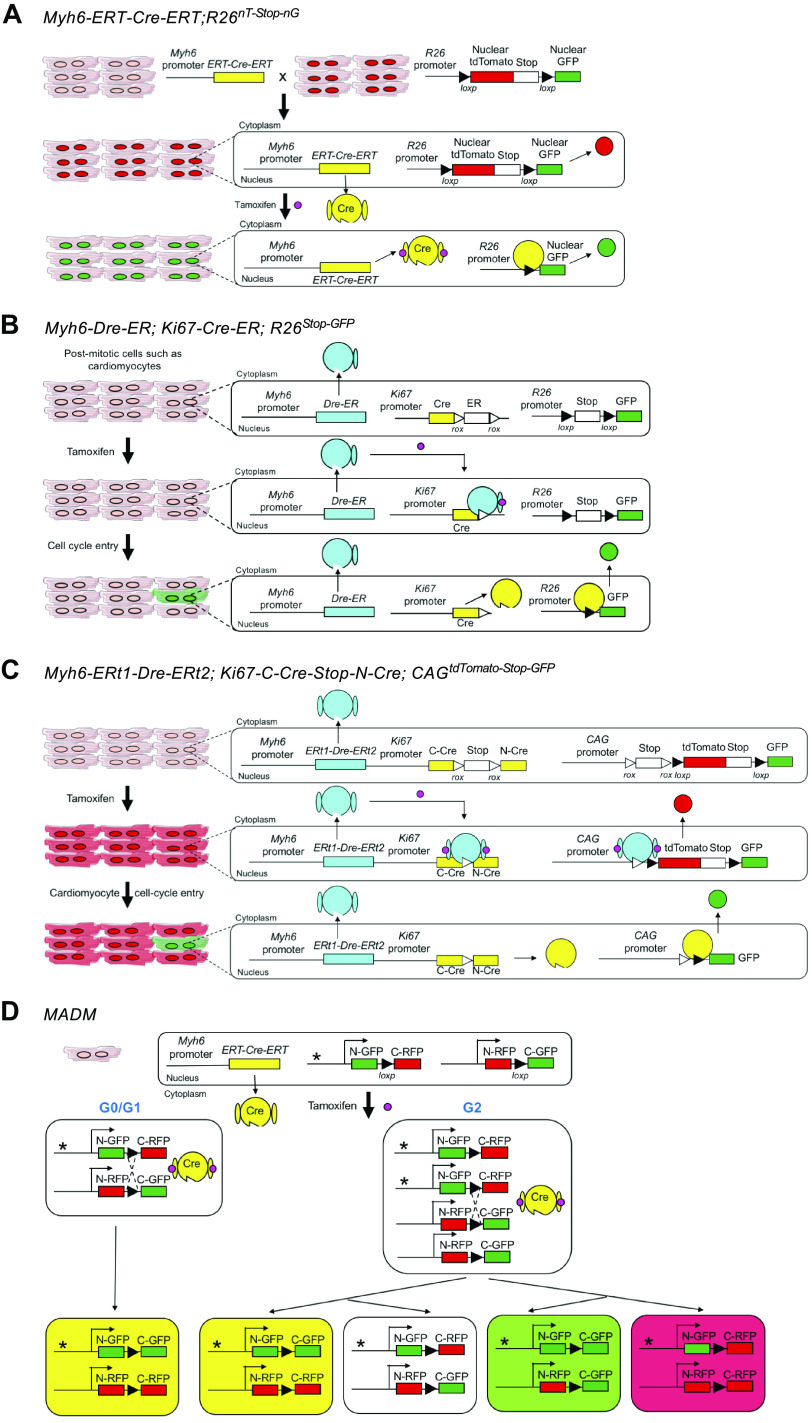

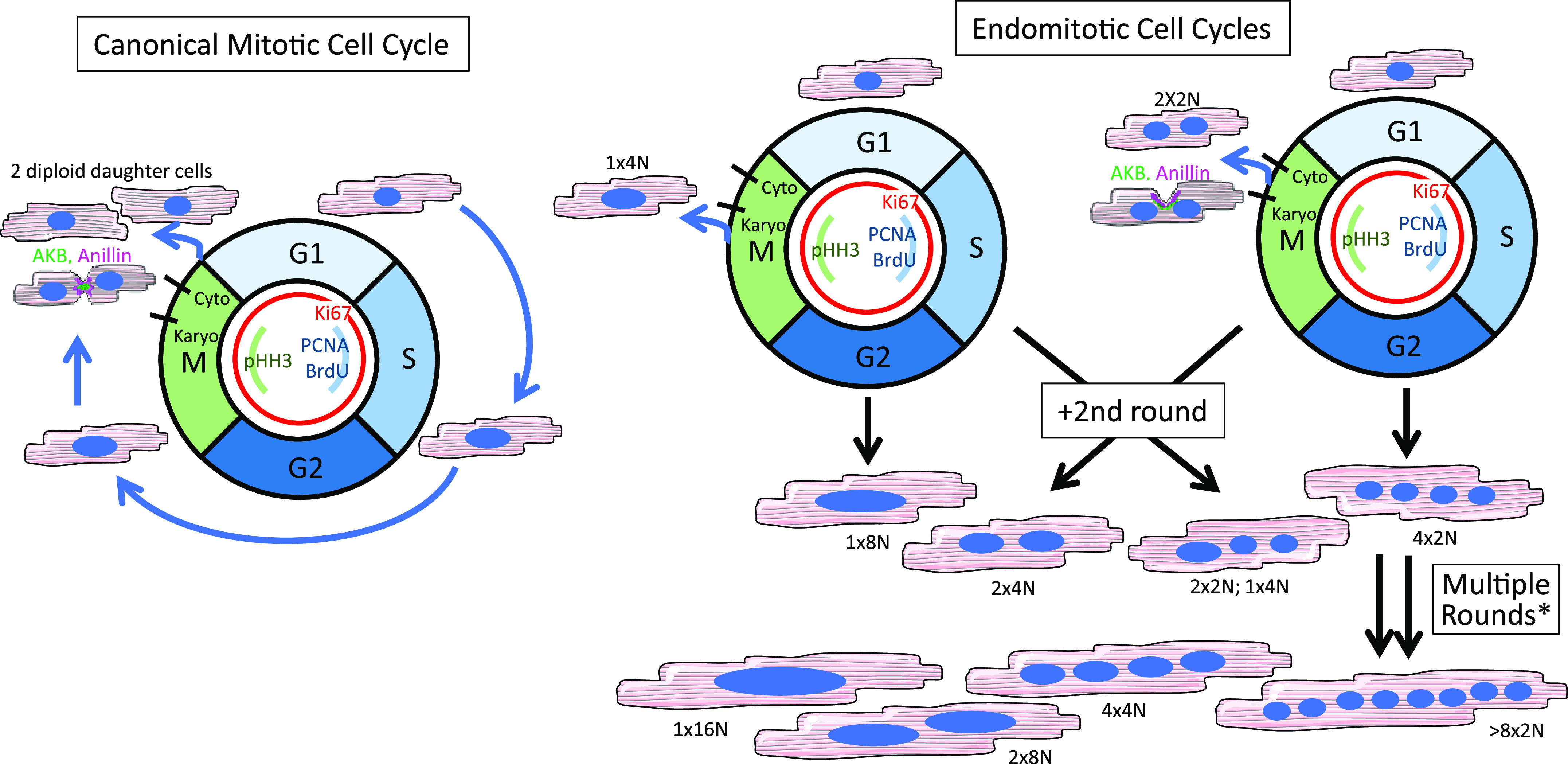

Figure 1.

Cardiomyocyte multinucleation and polyploidy are incurred by an alternative cell cycle. In the canonical mitotic cell cycle (left), a diploid cardiomyocyte progresses through the various stages ultimately dividing into two diploid daughter cells. By contrast, postnatal cardiomyocytes more frequently use a variant cell cycle, endomitosis (right), which results in either nuclear polyploidy and/or multinucleation depending at which stage the cell exits the cell cycle. Cardiomyocytes in many mammalian species can undergo one, two, or multiple rounds of endomitosis, resulting in heterogenous populations with variable ploidy and/or nucleation. *As seen in pigs (27) and human heart failure (28) among other scenarios.

UNAMBIGUOUS IDENTIFICATION OF CARDIOMYOCYTES WITH CELL-CYCLE ACTIVATION

The most prominently assessed phenotype across myocardial regeneration studies is the number of cardiomyocytes re-entering the cell cycle following an experimental manipulation. Most studies aptly use the expression of a sarcomeric protein, such as troponin T, I, or C, myosin heavy chain, or α-actinin, to identify cardiomyocytes in tissue sections, as the specificity of these markers to cardiomyocytes is well established. Recently, however some have argued for the need to label cardiomyocytes with a nuclear marker specifically, as most cell-cycle indicators [i.e., antigen Ki67, phospho-histone H3 (pHH3), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), incorporation of a thymidine analog, etc.] localize to the nucleus (Table 1) (30). Using nuclear markers has been driven by the conviction that it can be difficult to establish a cycling nucleus within a tissue section definitively belongs to a cardiomyocyte rather than a neighboring interstitial cell by cytoplasmic marker alone. For example, Ang et al. (31) estimated that researchers have a diagnostic accuracy of correctly identifying cardiomyocyte nuclei while excluding noncardiomyocyte nuclei, of 78%–83% when solely using the expression of sarcomeric proteins in the cytoplasm (31). This accuracy increased to ∼90% when the sarcomeric marker was paired with a wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) stain circumscribing the plasma membrane (31). Here, we highlight several strategies used in the field to ensure that cell-cycle active nuclei belong to cardiomyocytes, along with their advantages and potential limitations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Markers to identify cardiomyocyte nuclei in tissue sections

| Marker | Method | Limitation(s) | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myh6 “reporters” | Genetic allele | 1) requires extra allele(s) | (31, 32) |

| 2) locus may be turned off during “dedifferentiation” | |||

| nTnG | Genetic allele | Must be paired with a cardiomyocyte-specific Cre driver; thus, requires extra alleles | Fig 2A |

| Pcm1 | Antibody-based | Specificity only at the protein-localization level, not at the RNA level | (33–35) |

| May not stain all cardiomyocyte nuclei (theoretical) | |||

| Nkx2.5 | Antibody-based | Additional nonmyocyte populations following injury may still be unrecognized. | (34) |

| Mef2 | Antibody-based | Also expressed in smooth muscle cells | (34, 36, 37) |

| Additional nonmyocyte populations (with or without) injury may still be unrecognized. | |||

| Gata4 | Antibody-based | Also identifies some interstitial fibroblasts | (31, 34, 38–40) |

| Additional nonmyocyte populations (with or without) injury may still be unrecognized. |

Sarcomeric Labeling Paired with z-Stack Presentation of Confocal Microscopy

A common strategy used to conclude that a nucleus lies within a cardiomyocyte is confocal microscopy both with and without z-stack presentation to show that a nucleus is fully enveloped in all three dimensions by sarcomeric proteins (7, 11, 41, 42). This approach has many advantages: it is relatively straightforward, expression of sarcomeric proteins is highly specific to cardiomyocytes, and the number of well-established antibodies is numerous. However, it is not without limitations. First, definitive assessment requires the z-stack presentation, which is not always provided. In addition, confocal microscopy is time consuming making quantifications by this method quite tedious, and many laboratories simply provide pictures for publication, but do not actually quantify using confocal microscopy. Moreover, cardiomyocyte nuclei are 8–10 μm in diameter and many laboratories are using histological sectioning strategies with <10 µm sections; thus, in some instances it can be difficult to definitively conclude that a nucleus is surrounded on all sides by cytoplasmic sarcomeres.

Myh6-nLacZ Mouse and Other Myh6 Promoter-Driven Genetic Reporters

Recognizing the challenge of using a sarcomeric protein to identify cardiomyocyte nuclei, the Field laboratory developed a transgenic mouse line that expresses a nuclear LacZ under the control of the Myh6 (also known as α-myosin heavy chain, αMHC) promoter, thereby labeling nuclei actively expressing Myh6 (31). Other nuclear reporter systems such as Myh6 driving H2B-blue fluorescent protein (BFP) fusion protein (32) and immunostaining for nuclear Cre recombinase in the constitutive Myh6-Cre transgenic mouse (43) have been used. A related strategy would include pairing the tamoxifen-inducible Myh6-MerCreMer driver with a nuclear reporter such as the nuclearTomato-nuclearGFP mouse (nTnG, Jax Stock No. 023537). The nTnG mouse has a switchable cassette knocked into the ubiquitous Rosa26 locus, whereby the fluorescent reporter, tdTomato with a nuclear localization signal, is flanked by two loxP sites and is linked to green fluorescent protein (GFP) similarly tagged with a nuclear localization signal. In this case, one can label pre-existing cardiomyocyte nuclei by tamoxifen administration (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Genetic mouse models for assessing cardiomyocyte proliferation. A: Cre/lox system to depict how a cardiomyocyte-specific Cre driver, Myh6-MerCre-Mer, can be paired with a nuclear switch reporter, nuclear tdTomato loxP-STOP-loxP nuclear GFP (nTnG) to label only cardiomyocyte nuclei. B: mouse created by Bradley et al. (25) using a cardiomyocyte-specific tamoxifen inducible Dre recombinase paired with a cell cycle-specific (Ki67 promoter) Cre recombinase, which together allow for the identification of cycling cardiomyocytes. C: mouse created by Liu et al. (26) using a dual recombinase system again allowing for the identification of cycling cardiomyocytes. Notably, Liu et al. used multiple drivers of Dre recombinase; we are simply depicting one here. D: mosaic analysis with double marker (MADM) mouse created by Zong et al. (44), which shows cell division based on the recombination and inheritance of two reporters.

Although these reporters permit genetically engineered identification of myocyte nuclei, they are all dependent on Myh6 being expressed at the time of phenotypic assessment (in the case of expression reporters Myh6-nLacZ and Myh6-H2BBFP) or at the time of tamoxifen treatment (in the case of the Myh6-MerCreMer pairing). Multiple papers now suggest that a subset of cardiomyocytes, specifically those undergoing dedifferentiation and/or actively proliferating following injury, may silence Myh6 and turn on Myh7 (32, 33). In fact, Zhang et al. (32) exploited this aspect of cardiomyocyte response to injury in their experimental strategy to identify “dedifferentiating” cardiomyocytes, noting that not all pre-existing cardiomyocytes containing a tamoxifen-inducible Myh6-MerCreMer transgene continued to express the Myh6:H2B-BFP reporter after infarction. Thus, it is possible that using Myh6 reporter alleles might result in undercounting cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activity. Regarding prelabeling cardiomyocyte nuclei using the nTnG strategy, it is pertinent to recognize that most tamoxifen regimens do not result in recombination in 100% of cardiomyocytes (45, 46). In addition, from a technical perspective, these reporters require an extra allele, or multiple alleles, be bred into the desired genetic background, which in some situations can be prohibitive.

Pcm1 Expression

Pericentriolar material 1 (Pcm1), as its name indicates, was originally identified for its cell cycle-dependent association with the centrosomes. As such, it is ubiquitously expressed across cardiac cell types (34). However, in adult striated muscles, Pcm1 protein localizes to the perinuclear space surrounding the nuclear membrane (47, 48), and this relocalization in mouse cardiomyocytes happens at birth (35). Thus, many laboratories have used this marker for flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of cardiomyocyte nuclei in both mice and humans (3, 47). Because of its cell-cycle dependent role in centrosomes and microtubule organization, some in the field have raised a concern that its utility as a marker for mitotic cardiomyocytes may be compromised. Specifically, the question remains if Pcm1 remains localized to the perinuclear space in a mitotic cardiomyocyte, or if it returns to the centrosomes during chromosomal segregation. Cui et al. (33) examined the transcriptional profiles of Pcm1-positive versus Pcm1-negative cardiomyocyte nuclei by single nuclear RNA sequencing and concluded that Pcm1 could not only identify both embryonic and postnatal cardiomyocytes, but also that presorting based on Pcm1 introduced no overt bias toward cardiomyocyte subpopulations. If Pcm1 indeed returns to the centrioles during division, it could result in undercounting cycling cardiomyocytes, especially those completing true proliferation.

Nkx2.5 Expression

Nkx2.5 is a transcription factor responsible for early mesodermal and cardiomyocyte fate specification. However, by mid- to late gestation within the heart it becomes specific to cardiomyocytes. Nkx2.5 is readily detectable in neonatal cardiomyocytes (49, 50); however, its expression decreases with age. Its diminished expression at adult stages, combined with the high autofluorescence of cardiac tissue, can make this antigen difficult to detect in adult mammalian hearts, requiring precise fixation and staining procedures to visualize. Nevertheless, single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis on whole, naïve, adult hearts suggest that Nkx2.5 is reasonably specific to cardiomyocytes (34). To the best of our knowledge, it remains unknown if its expression changes after injury. One final theoretical concern, potentially relevant to all the transcription factors listed in this section, is that upon nuclear membrane breakdown during mitosis it is possible that a lowly expressed transcription factor may become too dilute to visualize.

Mef2 Expression

Like Nkx2.5, the Mef2 family of transcription factors has a prominent role in cardiac development and cardiomyocyte differentiation, wherein it is believed to activate muscle-specific genes. Postnatally, Mef2a/c/d are expressed in cardiomyocytes making them plausible markers to identify myocyte nuclei. One limitation for using this family of transcription factors to identify cardiomyocytes is that they are also expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells (36). However, in the uninjured neonatal heart, smooth muscle cells display apparently lower levels of Mef2 than cardiomyocyte nuclei (37). Furthermore, because smooth muscle cells are localized around small to large vessels, positive Mef2 signals arising from smooth muscle cells can be ruled out by morphological features. Recent single-cell mRNA expression data also suggest that some Mef2 family members are also expressed in endothelial cells and fibroblasts (34), however these expression patterns should be confirmed at the protein level.

Gata4 Expression

The final nuclear marker we discuss here is the transcription factor Gata4. Gata4 is highly expressed in cardiomyocytes and while this transcription factor can be observed in cardiomyocyte nuclei, at least one study has observed cytoplasmic localization of Gata4 in activated cardiomyocytes in a repair scenario (51). Like Mef2, Gata4 is reported to be expressed in nonmyocyte populations within the heart. In the uninjured mouse heart, Ang et al. (31) determined that 90% of β-gal-positive nuclei in Myh6-nLacZ mice co-stained for Gata4, whereas 30% of Gata4-positive nuclei were β-gal-negative, which the authors used to conclude that Gata4 in the uninjured setting has an overall diagnostic accuracy of ∼90%, comparable with sarcomeric stains when combined with WGA (31). Multiple studies have demonstrated that Gata4-positive nonmyocytes overlap with subpopulations of interstitial fibroblasts (34, 38–40), which are more difficult to anatomically exclude than Mef2-positive smooth muscle cells. To the best of our knowledge, it remains unknown if Gata4 expression within the interstitial fibroblast subpopulation changes during fibrotic-based injury response. Such a possibility may confound its use in the injury context.

Summary.

Sarcomeric proteins are without question specific to cardiomyocytes and remain the most reliable marker of a cardiomyocyte. However, when attempting to assess co-localization of a nuclear localized cell-cycle marker in tissue sections, some in the field are beginning to request that cardiomyocytes coincidently be identified using a nuclear antigen. We outline several options used by the field in Table 2. Notably, each has its own set of limitations. Furthermore, many of these markers are prime examples of science in flux; as new data come out, particularly in the advent of single-cell transcriptomics, it is wise to remain cognizant of any one marker’s specificity to cardiomyocytes. With these limitations in mind, we recommend using multiple strategies to be confident of conclusions related to cardiomyocyte proliferation. Ideally, one could pair both sarcomeric and nuclear antigen detection in the same section with a microscope capable of four channel detection (i.e., DNA dye; cardiomyocyte nuclear marker, cell-cycle indicator, and sarcomeric antigen). Much of what we describe here is relevant to rodent models; however, the issue is only more challenging in large mammals where genetic tools are underdeveloped and antibodies lack species reactivity or have not been sufficiently tested for cardiomyocyte specificity.

DISCRIMINATING CARDIOMYOCYTE CELL-CYCLE ACTIVATION FROM BONA FIDE PROLIFERATION

A common source of confusion surrounding quantification of cell-cycle activation in cardiomyocytes is with the use of the term “proliferation.” Many in the field use one or even several common cell-cycle indicators (i.e., Ki67—all cycling cells; pHH3—mitosis; PCNA—S-phase; and thymidine analog incorporation—DNA synthesis over a labeling period; Table 1) to claim cardiomyocytes have proliferated. However, after birth, mammalian cardiomyocytes do not primarily use the canonical mitotic cell-cycle, and a nucleus positive for any of these markers does not necessarily indicate true proliferation has taken place or will take place. Instead, postnatal cardiomyocytes rely heavily on an alternative cell cycle known as endomitosis or endoreplication, whereby cardiomyocytes re-enter the cell cycle, complete DNA synthesis, and enter mitosis, however they mostly fail to complete either karyokinesis or cytokinesis (29). In these latter endomitosis-based scenarios, cardiomyocytes still express all the same cell-cycle indicators, such as Ki67, pHH3, and PCNA, yet no new cell is born. Instead, cardiomyocytes with varying combinations of multinucleation and nuclear polyploidy ensue (Fig. 1). Measuring expression of cell-cycle markers is just the beginning of determining if true cardiomyocyte proliferation has taken place, and use of the term “proliferation” should be restricted to scenarios where cytokinesis and/or birth of two daughter cells from one original cell can be proven. In this section, we provide several strategies for assessing cytokinesis and true proliferation and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Measuring Aurora Kinase B Expression

Aurora kinase B (AKB) has many roles throughout the cell cycle (Table 1). It localizes to the heterochromatin in early mitosis, to the microtubule spindle during anaphase, to the cell cortex during contractile ring formation, and finally to the midbody during cytokinesis (52). It is this final, classic display at the cytokinetic furrow that has prompted many in the field to use it as a quantifiable marker of cardiomyocytes completing cytokinesis through a straightforward antibody stain. However, it comes with several notable limitations. First, it is an incredibly transient and rare event, with most reports concluding that only 0.01%–0.04% of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes stain positively (53–55). This low frequency can make identifying differences between experimental groups quite difficult. Furthermore, it can be challenging to definitively establish that the labeled cytokinetic furrow belongs to a cardiomyocyte and not to a neighboring interstitial cell. Finally, AKB can be detected at the cleavage furrow of cells that may ultimately fail to complete cytokinesis and undergo binucleation instead (22, 23) (Fig. 1). Thus, although AKB is a marker of cytokinesis, it is not always a marker of complete cell division. Consequently, it is best used in conjunction with additional approaches to support conclusions of cardiomyocyte division and proliferation.

Anillin Expression and Anillin-GFP Reporter

Anillin, like AKB, has many roles and positions throughout the cell cycle, ultimately localizing to the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis (Table 1), making it another attractive marker for assessing division. However, also like AKB, Anillin can localize to the cleavage furrow even when cytokinesis will fail. Although several studies examining neonatal cardiomyocytes in vitro have convincingly shown that asymmetric localization of both AKB and Anillin at the cleavage furrow enable unequivocal identification of binucleation over cytokinesis (22, 23; Fig. 1), such a subtlety can be difficult to convincingly deduce in histological sections. Furthermore, as aforementioned, definitively placing Anillin foci within cardiomyocytes rather than a neighboring cell presents an additional limitation. Recently, Hesse et al. (23) generated a new transgenic mouse wherein an eGFP-Anillin fusion protein is expressed downstream of the Myh6 promoter. This construct addresses concerns surrounding colocalization with a cardiomyocyte versus an interstitial neighbor, although assessing asymmetry within the cell specifically in tissue sections may still present a limitation.

Single-Cell Suspension Method

To argue cardiomyocytes have definitively divided, this method pairs thymidine analog incorporation with assessment of nucleation and ploidy by DNA dyes (e.g., DAPI, Hoechst, and DyeCycles) following enzymatic digestion of whole hearts into a single-cell suspension. The simple premise is that, if a cardiomyocyte incorporates a thymidine analog (e.g., EdU or BrdU) during the labeling period and is determined to be both mononuclear and diploid at the time of analysis, then it must have definitively completed cytokinesis (29). This method was first introduced by Patterson et al. (7) using intact whole cells to assess nucleation, while extracting nuclei to separately assess nuclear ploidy by flow cytometry. One limitation of this original experimental design is that by performing flow cytometry on isolated nuclei, the details of how nucleation and ploidy were coupled within a single cell were lost and assumptions needed to be made. The procedure has since been refined and improved, such that nuclear ploidy is also measured on intact cells by microscopy (8, 37). In these newer renditions, the DNA content of a single nucleus is assessed by quantifying the sum fluorescence intensity of the DNA dye, accounting for both size (i.e., number of pixels) and brightness of each pixel; this is similar in concept to how a flow cytometer equates fluorescence intensity but does so using image-based software such as ImageJ or NIS Elements. The final value assigned to an individual nucleus is then normalized to presumed diploid nuclei [e.g., noncardiomyocytes (8), or nuclei from tri- and tetranucleated cardiomyocytes (37)]. The enhancement gained from this refined methodology is that one can be confident that a diploid nucleus resides in a mono- versus bi- or multinucleated cardiomyocyte, specifically; thus, ploidy and nucleation data remain fully coupled.

Considering this methodology as a whole, it does definitively identify cardiomyocytes that have completed cell division and it can be performed in any experimental context and with most animal models, as no additional alleles must be crossed in (see other methods mentioned later in this section). However, it is not without caveats. First, because hearts are enzymatically digested into single-cell suspensions all spatial information is lost. Digestions can be inefficient, particularly in regions of ischemia and dense fibrosis, which may be exactly where true cardiomyocyte proliferation is taking place (25, 26). Digestions also inevitably involve some level of cell death and it remains unknown if different cardiomyocyte subpopulations are more or less susceptible. Furthermore, this procedure requires single-cell suspensions; thus, it cannot be assessed on the same hearts used to measure histological-based evaluations of regeneration (e.g., scar size), thereby requiring a separate cohort to complete the analysis. In addition, there may be cellular consequences due to the incorporation of modified nucleotides (i.e., EdU or BrdU) into DNA on proliferative capacity and cell fate with extended exposure required with this protocol. Finally, the method may result in undercounting as it does not account for other possible proliferation scenarios like those reported in the hepatocyte field whereby binucleated cells undergo DNA synthesis and then form a single cytokinetic furrow ultimately resulting in two mononuclear, tetraploid cells (56, 57), along with other possible outcomes from the “ploidy reversal” hypothesis (58, 59). To the best of our knowledge, such an occurrence has not yet been identified in cardiomyocytes. Despite these caveats, the method is a valuable tool given its potential for universal application.

Sparse Labeling and Clonal Analysis

This method also has a very simple premise. Cells are sparsely and stochastically labeled through a variety of genetically engineered reporters before or at the time of injury, such that single-labeled cells would be found if assessed immediately. However, following a chase period, small clusters of cells will be found instead suggesting clonal expansion and division. Two laboratories have applied this method in the heart using dual-recombinase lineage tracing mice (25, 26). Bradley et al. created a mouse with a tamoxifen-inducible Dre recombinase under the control of the Myh6 promoter, Cre recombinase with the C- and N-termini interrupted by a roxP-STOP-roxP cassette under the control of the Ki67 promoter, and a switch reporter that required both Cre and Dre expression to obtain GFP expression. The result being that both the cardiomyocyte gene, Myh6, and the cell-cycle indicator, Ki67, were required to label the cells (Fig. 2B). Using this mouse, authors were able to label cycling cardiomyocytes and identified that following ischemia/reperfusion injury ∼90% of labeled cells were found as singlets and ∼10% were found as doublets, the latter indicating proliferation. Observed doublets were preferentially found in the infarct border zone (25). Independently, Liu et al. generated a novel mouse in which Cre recombinase, under control of the Ki67 promoter, is fused to a roxP-flanked modified estrogen receptor sequence. With this mouse, exposure to Dre recombinase cleaves out the modified estrogen receptor component allowing for nuclear access of Cre and cleavage of a loxP-STOP-loxP sequence of a second transgene driving GFP expression. The authors introduced Dre recombinase on demand by various methods to “prime” the reporter system (i.e., by removing the modified estrogen receptor sequence that prevents nuclear access), including adeno-associated virus (AAV)9 administration and by crossing it to a Tnnt2-DreER allele. In each case, a GFP reporter could only be induced if the Ki67-Cre was “primed,” resulting in a scenario where only cycling cardiomyocytes are labeled (Fig. 2C). Here, the authors found that ∼13% of GFP-positive cells were in doublets, again indicating proliferation, and that cycling cells were preferentially found in the border and subendocardial zones. Experiments were repeated with the Cre recombinase under the control of the S/G2-phase Cyclin A2 (Ccna2) promoter (26). One caveat to these models is that the tamoxifen-inducibility of the system is removed as part of the labeling scheme, thereby removing the true lineage tracing capacity of the system. Thus, it remains possible that some doublets are instead reflective of two neighboring cardiomyocytes both entering the cell cycle rather than true cell division by a single myocyte.

The advantage of systems such as those described earlier is that the analysis is performed in situ and relevant information regarding localization is preserved. In the liver, where regeneration is more robust, similar approaches could be achieved with a low titer viral induction of a Cre recombinase, making this method feasible on almost any genetic background. In the heart, on the other hand, proliferation is restricted to a small, still unknown population of cardiomyocytes and therefore an approach that targets those cells specifically, such as the Ki67-based systems developed by Liu et al. (26) and Bradley et al. (25) are likely required. Naturally, these involve complicated breeding schemes which can make their application in many experiments prohibitive. Because adjacent or nearby labeled cells will not necessarily be aligned in the same histological plane, consecutive tissue collection and/or z-stacked confocal imaging is required for appropriate quantification. The analysis, like all strategies to assess cytokinesis, is labor intensive, however, it does not make assumptions regarding possible ploidy-based outcomes as the single-cell suspension method does. A pair or cluster of labeled cells, regardless of their nucleation and/or nuclear ploidy, would be counted.

MADM Mouse

Another genetically engineered mouse that permits the assessment of cytokinesis is the mosaic analysis with double markers (MADM) mouse. First created by Zong et al. (44), this mouse relies on interchromosomal Cre-mediated recombinations and probability of random chromosomal segregation to identify definitive cytokinesis. Briefly, the N-terminus of GFP is genetically paired with the C-terminus of red fluorescent protein (RFP), each separated by a single loxP site. A reciprocal cassette of the opposite combination is found on the other chromosome. This construct can be crossed with any Cre driver mouse, such that if Cre is present interchromosomal recombinations can rearrange the constructs, aligning the N- and C-termini of the respective reporters. Importantly, Cre-mediated recombination taking place without DNA synthesis or cell-cycle activation would always result in a double (GFP and RFP) positive cell. On the other hand, if recombination takes place in conjunction with cell-cycle activation, and if cytokinesis follows, then sister cells—one labeled with only GFP and one labeled only with RFP—will be generated; this is sometimes referred to as “twin spots” (Fig. 2D). This was exactly the logic Ali et al. (6) used when determining if pre-existing cardiomyocytes (i.e., using a Myh6-MerCreMer mouse) completed cytokinesis.

This method for assessing cytokinesis requires three alleles be present in an experimental animal, which can prove prohibitive in certain scenarios. On the other hand, analysis is performed in situ and assumptions on cardiomyocyte ploidy need not be committed, making it a desirable method. One caveat unique to this method is that cytokinetic events are likely undercounted because based on the laws of chromosomal segregation both unlabeled and double-positive cells are possible outcomes following true cell division. Unfortunately, these specific combinations are also possible in the event that either no recombination has taken place (unlabeled) or that recombination has taken place in the absence of DNA synthesis (double labeled), thus unlabeled and double-labeled cells must be excluded as one cannot draw a definitive conclusion regarding those cells. As aforementioned, one final limitation with this strategy lies with the identification of “twin spots,” which may require consecutive tissue collection and/or thick tissue sections combined with z-stacked confocal imaging to capture if the two sister cells are not aligned in the same histological plane. Notably Ali et al. (6) and Zong et al. (44) were both able to identify “twin spots,” where adjacent, presumably sister cardiomyocytes were singly labeled with GFP and RFP, respectively. However, “twin spots” are not always apparent and many laboratories that use the MADM mouse simply resort to quantifying single-positive cardiomyocytes, which may not be truly representative of fully completed cell division.

Video Microscopy

This method cultures isolated cardiomyocytes to follow cell division by video microscopy. Many laboratories use this strategy on neonatal cardiomyocytes (60–62), however some laboratories have extended it to adult cardiomyocytes as well (9, 63). In addition, video microscopy has been successfully paired with cell-cycle reporter systems [i.e., FUCCI (24) and Anillin-GFP (23)], which allow for the identification and quantification of endomitotic progeny in addition to cytokinetic events (23, 64). The method has some clear advantages, namely that it directly visualizes cytokinesis or usage of other cell-cycle variants (i.e., endomitosis) and it can be performed on any genetic background. On the other hand, it takes cardiomyocytes out of their natural environment and the molecular profile and proliferative potential of the cell could change as a result (65, 66) and therefore might not represent in vivo scenarios.

Summary.

After birth, cardiomyocytes preferentially use an alternative cell cycle, endomitosis, which results in further polyploidization rather than division into two daughter cells. Therefore, it can be challenging using standard approaches to assess if a cardiomyocyte has truly divided. Claims that proliferation has taken place require assessment(s) of true cell division, and traditional markers of cytokinesis (e.g., staining of AKB) are insufficient on their own in most cases. If one of the aforementioned methods to assess cytokinesis, or another method not discussed here, has not been used, it is only appropriate to claim that cell-cycle activation has taken place. The term “proliferation” should be strictly reserved for scenarios where division has been assessed. For investigators who study zebrafish or other models in which regeneration is highly efficient, we also recommend the importance of distinguishing cell-cycle activity from proliferation and advise that experimental approaches to confirm proliferation be used where possible. We acknowledge that each method described here is both laborious and not without limitations; thus, efforts to identify additional strategies to assess cytokinesis are warranted.

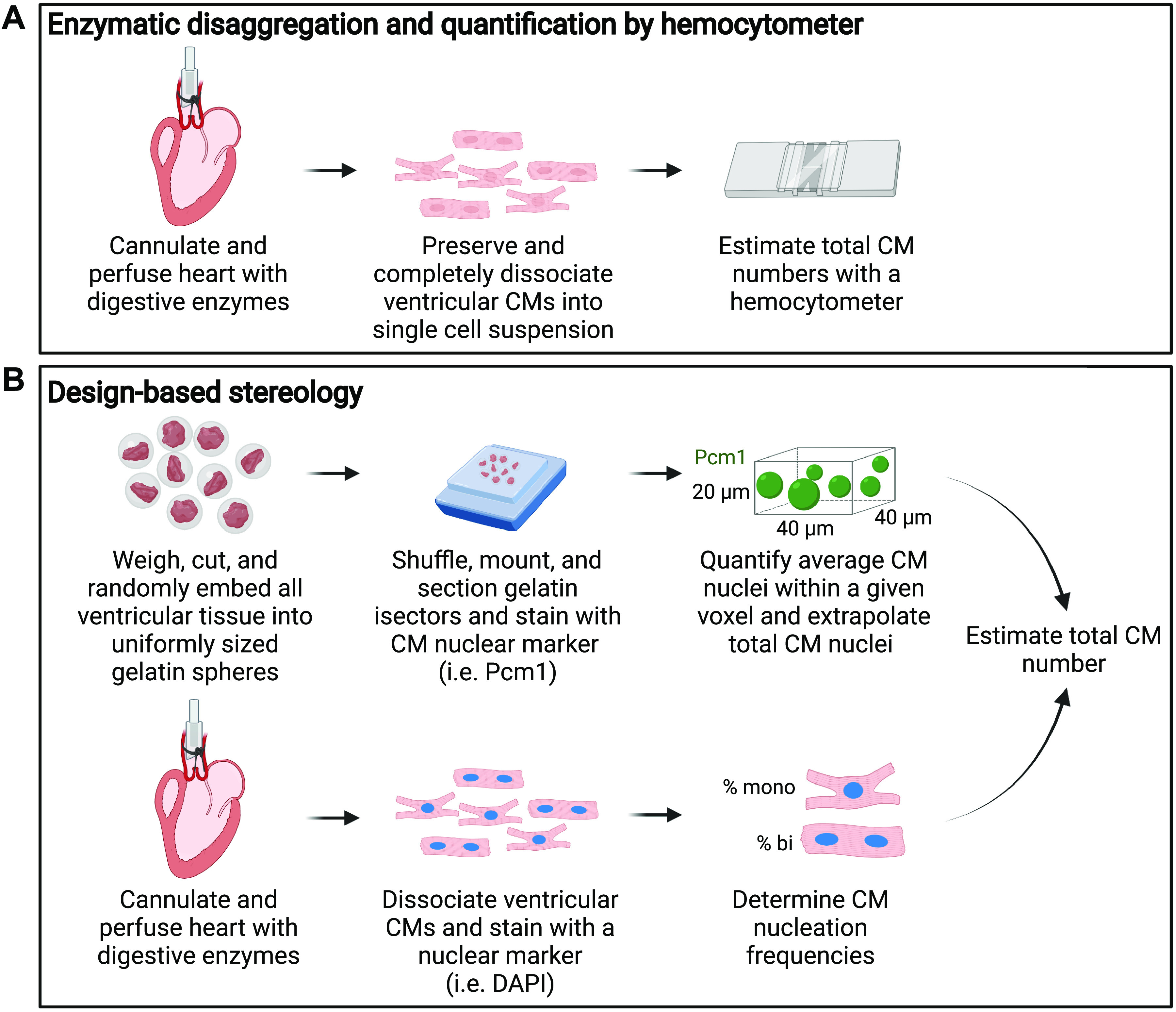

METHODOLOGIES FOR QUANTIFYING TOTAL CARDIOMYOCYTE NUMBERS

A complimentary approach to cell-cycle marker analysis is to infer complete cardiomyocyte cell division by estimating the associated increase in total cardiomyocyte numbers in the entire heart, also known as “endowment.” Currently, two predominant strategies are used: 1) enzymatic disaggregation and quantification and 2) design-based stereology. Variability in results obtained using these two methods have led to disagreements in the field regarding when final cardiomyocyte numbers are established during postnatal development, as well as the total number of cardiomyocytes present in the adult ventricular myocardium. Studies using the enzymatic disaggregation approach in the C57Bl/6 mouse strain suggest that total cardiomyocyte numbers in the heart increase from ∼900,000 at postnatal day 1 (P1), to 1.3 million (M) at P14, and 1.7 M at P18, after which no further increases occur (67); the authors used these data to support a model wherein cardiomyocytes undergo a final proliferative burst at P15, thereby increasing cardiomyocyte numbers during preadolescence. In contrast, estimation of cardiomyocyte numbers using the design-based stereology approach revealed that C57Bl/6N mice possess 1.7 M cardiomyocytes at P2, 2.3 M at P5, and 2.6 M by P11, which remains constant thereafter (68); here, the authors concluded that final cardiomyocyte numbers are set within the first ∼10 days of postnatal development, and that a proliferative burst does not occur after this time point. Although the investigated time points after birth were different, these two studies highlight the discrepancies that can potentially arise from the two methods. Not only did the two methods reach conflicting conclusions regarding the timing of postnatal cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest, but the final endowment numbers differ by almost 1 M cardiomyocytes, a 1.5-fold discrepancy. In general, it appears that enzymatic disaggregation results in lower numbers than design-based stereology. In addition, genetic background may also contribute to variability; for example, two studies that used design-based stereology estimated ∼2.3 M cardiomyocytes in a C57Bl/6;CD-1 mixed background at P14 (8), whereas ∼4.8 M cardiomyocytes—more than twofold increase—were estimated in a pure CD-1 outbred strain at the same stage (69). Although these two studies were not performed simultaneously, they were performed in the same laboratory. Acknowledging these discrepancies, here we provide an overview of these two methods, highlighting caveats associated with each approach.

Enzymatic Disaggregation and Quantification by Hemocytometer

In this method, the heart is rapidly excised, and the aorta is cannulated and attached to a Langendorff perfusion apparatus. Blood is then flushed out of the coronary vessels by retrograde perfusion, sometimes followed by a light fixation step to preserve cardiomyocyte structure (Fig. 3A) (70). The heart is then perfused with a solution containing digestive enzymes (i.e., collagenase type 2). Several groups have had success with an alternative to retroaortic perfusion, which entails simple injection of dissociation reagents into the lumen of the left ventricle concomitant with clamping of the ascending aorta thereby forcing the solution through the coronary vasculature (71, 72). Following digestion, the ventricles are isolated and gently triturated to release dissociated cardiomyocytes, which are then directly quantified on a hemocytometer. Cardiomyocytes are easily distinguished from noncardiomyocyte cells by their size and rod-shaped morphology.

Figure 3.

Methods for assessing cardiomyocyte endowment. A: enzymatic disaggregation and quantification by hemocytometer rely on retrograde perfusion of digestive enzymes through the coronary vasculature to generate a single-cell suspension, which can then be quantified by hemocytometer. B: design-based stereology is performed after mincing whole ventricular tissue into uniformly sized spheres (isectors), which are then randomly embedded into gelatin blocks, sectioned, and stained for a nuclear cardiomyocyte (CM) marker. Total CM nuclei are quantified. In parallel, the relative distribution of mono-, bi-, tri-, and tetranucleated CMs are quantified microscopically to estimate the total number of CMs.

An advantage of this approach is its relative speed and theoretical simplicity. However, this method tends to have wide technical variability, requiring increased animal numbers to distinguish biological effects from experimental noise. Technical issues, including incomplete tissue dissociation, cell death (digestion before fixation), and cell fragmentation (fixation before digestion) during the processing can contribute to variability. These issues are further confounded in the context of fibrotic injury, where digestion is more difficult, and the additional variable of injury severity would also come into play. Hence, additional caution is recommended when using this strategy to quantify cardiomyocyte numbers, especially in regeneration studies wherein increased numbers may be small yet functionally significant.

Design-Based Stereology

Design-based stereology estimates total cardiomyocyte numbers without the need for complete cardiac dissociation. Freshly isolated ventricles are weighed, cut into small pieces, and randomized before embedding in gelatin spheres of uniform size. Gelatin isotropic sections (isectors) are then generated and shuffled, which effectively randomizes the orientation of the ventricular tissue embedded within. Individual isectors are again randomly selected, positioned, frozen in mounting media, cryosectioned, and immunostained with a cardiomyocyte nuclear marker. The average number of cardiomyocyte nuclei is then determined within a defined voxel size (i.e., 40 mm × 40 mm × 20 mm), and the total number of cardiomyocyte nuclei in the entire heart is extrapolated. To calculate cardiomyocyte numbers from the number of cardiomyocyte nuclei per heart, the relative abundance of mononucleated, binucleated, and multinucleated cardiomyocytes must be quantified in parallel, but under similar experimental conditions (Fig. 3B) (8, 68, 69).

If design-based rules are followed in this stereological approach, assumptions on cardiomyocyte shape, size, orientation, and distribution should be mitigated, permitting an unbiased assessment of total cardiomyocyte numbers. However, this method is not without its own caveats and disadvantages. Design-based stereology relies on extrapolations from measurements in a small fraction of the heart to estimate cardiomyocyte numbers within the entire ventricle. The effects of tissue handling and processing on shrinkage or expansion are not thoroughly characterized, which could affect estimation of cardiomyocyte density and downstream results. Estimation of ventricular volume is typically calculated by multiplying ventricular mass by cardiac tissue density, defined as 1.06 g/cm3, a reference value derived from the adult rat myocardium (73). It is possible, perhaps even likely, that cardiac tissue densities differ with experimental treatments, across regions of the myocardium, and across developmental stages, thereby confounding interpretation. Furthermore, conversion to total cardiomyocyte numbers requires the assessment of cardiomyocyte nucleation frequencies in independent experiments, which requires additional time and resources, adding yet another source of variability. Finally, stereological estimation of cardiomyocyte numbers in the context of injury, where cardiomyocyte distribution in the heart is significantly altered, can present additional complexities.

Summary.

Given the vastly different results generated by enzymatic disassociation versus in situ stereology, it is difficult to know for certain which generates the more accurate results. We can say with some confidence that enzymatic dissociation is likely to result in an undercounting, such that the true numbers of ventricular cardiomyocytes in C57Bl/6 mice likely fall between the discrepant values offered by Naqvi et al. (67) and Alkass et al. (68). For many other related phenotypic assessments, including evaluation of cardiomyocyte ploidy, Langendorff-based digestions remain the best method available for now. Following cardiac injury, the high degree of complexity introduced by fibrosis may add additional caveats to consider for both techniques. Thus, additional caution when assessing cardiomyocyte endowment in the injury context is warranted. Certainly, this is an area where development of new experimental strategies could be helpful.

USING GENETICALLY ENGINEERED MODELS TO IDENTIFY MECHANISMS UNDERLYING CARDIOMYOCYTE PROLIFERATION

Among our strongest tools for assessing a gene’s role in cardiomyocyte proliferation and myocardial regeneration is the use of genetically engineered animal models. These approaches are widely used in mice, and the technology to create such models not only in mice but more recently large animal models, is rapidly improving. However, if a study lacks appropriate controls, the interpretation of experimental outcomes will likely be flawed. Here, we discuss various genetic mouse models that are used to assess the mechanisms underlying cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration, presenting recommendations intended to ensure that appropriate experimental controls are included to avoid erroneous conclusions.

Cre/lox-Based Manipulations

Many studies have used gene of interest or reverse genetics approaches to uncover underlying mechanisms of cardiomyocyte proliferation. Cardiomyocyte-specific gene knockout using Cre/lox technology has clearly been the most common approach. In such experiments, a gene of interest is targeted to include two loxP sites (the consensus sequences for Cre recombinase) flanking the exon containing the start codon or another domain deemed necessary for gene function. Separately, Cre recombinase, a bacteriophage-derived enzyme that can cause recombination between two loxP sequences, is expressed under the control of a cardiomyocyte-specific promoter. Depending on the orientation of the loxP sequences, the presence of Cre will mediate excision or inversion of the DNA fragment contained by the loxP sites, thereby resulting in a gene knockout or loss-of-function. Alternative engineering can also use this system to instead conditionally overexpress a gene of interest. Notably, additional recombinases exist, e.g., Flp and Dre, which work in a similar fashion to Cre recombinase, but recognize their own unique consensus sequences (Flp/Frt and Dre/rox).

Unfortunately, off-target effects ascribed to Cre mandate the inclusion of appropriate controls. The cardiovascular field has argued for proper Cre controls for over a decade, noting that both cardiomyocyte-specific constitutive Cre recombinase and inducible-Cre recombinase fused to tamoxifen-inducible estrogen receptor result in increased fibrosis, impaired cardiac function, cardiotoxicity, and sometimes premature death (46, 74–78). More recently, and highly relevant to the issue of cardiomyocyte proliferation specifically, coauthors of this review have added inappropriate activation of the cardiomyocyte cell cycle to the list of reasons why off-target effects of Cre must be appropriately controlled (79). In their report, Wang et al. (79), using mice expressing the widely used Myh6-MerCreMer transgene (Jax Stock No. 005657) (45), observed sporadic cell-cycle activation in both myocyte and nonmyocyte populations in the adult heart up to 6 days after injecting tamoxifen. The study quantified thymidine analog incorporation, along with protein expression of Ki67 and pHH3, and RNA expression of cyclin A2, cyclin B1, and Cdk1, supporting a cell-cycle activation conclusion rather than a DNA damage response, and emphasizing the need for appropriate tamoxifen-treated and Cre-positive controls in studies assessing cardiomyocyte proliferation.

With these caveats in mind, if a phenotype is observed using a breeding scheme that compares Cre-positive to Cre-negative animals, one cannot be certain if the phenotype is due to the targeted gene of interest, or to off-target effects of the Cre/lox system. Conversely, if one hypothesizes that cardiac regeneration and functional recovery will result from manipulating a gene of interest, but Cre is not properly controlled, the anticipated benefits may be obscured by Cre-inflicted damage. These concerns extend well beyond cardiomyocyte-specific Cre lines as Cre-mediated toxicity and DNA damage in the absence of loxP sites has been observed in a wide variety of cell types (80–83). As the field of cardiac repair advances to consider roles played by the multitude of other cell types present following myocardial injury, it will be imperative to anticipate potential off-target effects of Cre recombinase in these cells. We highlight some of the Cre driver lines pertinent to cardiomyocyte biology in Table 3 (45, 84–89).

Table 3.

Cardiomyocyte-specific Cre driver mouse alleles

| Marker | JAX Stock | Expression Profile/Limitation(s) | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myh6-Cre | JAX 011038 | Transgenic allele, exact insertion unknown (Chr 5) | (84) |

| >90% recombination in cardiomyocytes | |||

| Recombination observed as early as embryonic day 10 (E10) | |||

| Reported phenotypes from Cre alone | |||

| Myh6-Cre | JAX 009074 | Transgenic allele, integrated into the X-chromosome | (85, 86) |

| >70% recombination in cardiomyocytes | |||

| Myh6-MerCreMer | JAX 005657 | Transgenic allele, inserted within A1CF gene | (45) |

| Tamoxifen-inducible expression, specific to cardiomyocytes | |||

| Tamoxifen regimen influences efficiency of recombination | |||

| Reported phenotypes from Cre alone | |||

| Tnnt2-Cre | JAX 024240 | Transgenic allele using the rat troponin T2 promoter | (87) |

| Cardiomyocyte-specific | |||

| Recombination observed as early as E7.5 in cardiac crescent | |||

| 60% of hemizygous females are infertile | |||

| Myh7-Cre | Transgenic allele using 5.6 kb of the mouse Myh7 promoter | (88) | |

| Recombination in embryonic cardiomyocytes, not complete | |||

| Also expressed in skeletal muscle | |||

| Myl2-Cre | JAX 029465 | Cre knock-in replacing exon 1 and 2 of endogenous Myl2 | (89) |

| Ventricular expression as early as E9 | |||

| Hemizygous are viable and fertile, homozygous die at E12.5 |

Technological Advances and Alternatives to the Cre/lox System

A more recent alternative technology to knock out genes-of-interest in a cardiomyocyte-specific manner uses CRISPR. Here, a mouse line that conditionally expresses Cas9 under an ubiquitous promoter is injected with a recombinant AAV9 that expresses both Cre recombinase to remove the conditional block on Cas9 expression and guide RNAs (90). Cardiomyocyte specificity is achieved by expressing Cre under control of a virally encoded cardiomyocyte-specific promoter. A key advantage of this approach is that it avoids the lengthy breeding time necessary to cross multiple mouse lines (e.g., Cre allele and the conditional target gene alleles) together. However, the same need to properly control for Cre expression as described earlier also applies when using this technology. Furthermore, one must recognize that somatic mutations created by CRISPR/Cas9 technology will be heterogeneous in nature, such that each affected cell may have a different mutation to the gene of interest. Alternatively, it is now commonplace to create germline mutations in mice using CRISPR/Cas9 manipulation of fertilized eggs. The phenotypic consequences of such a mutation do not necessarily relate to a cardiomyocyte-specific function; however, as the sophistication of the field advances, it is likely that point mutations in cardiomyocyte enhancers of genes of interest will become more commonplace, and in principle could achieve cardiomyocyte-specific disruption of gene function without the need for Cre/lox approaches.

Mouse strain background can add another layer of complexity that is frequently overlooked. Strain background can have a significant influence on biological parameters, including those related to cardiomyocyte proliferation (7). In a standard conditional mutation approach, if the Cre allele and the conditional gene originate on different inbred backgrounds or on outbred backgrounds, the progeny that is used experimentally to study regeneration will have genetic differences beyond simply the conditional gene of interest. It is important to incorporate awareness of this source of experimental variation into the study design, ideally by using a defined strain background for genetic studies. Conversely, rather than being a variable that needs to be controlled, the natural genetic variation that exists across laboratory-derived inbred mouse strains can be used in a forward genetic approach to identify new genes relevant to cardiomyocyte proliferation and regeneration. The approach can use recovery after injury as the experimental end point of the screen (91) or use a more high throughput surrogate that is (or is likely to be) relevant to regeneration (7). Because in such approaches the underlying genetic variation is present in all cells and is inherently homozygous viable, a completely different set of genes relevant to regeneration might be identified compared with those (typically one’s own gene of interest) that can only be studied by tissue-specific mutagenesis. For example, gene function in noncardiomyocyte cell types might be uncovered, as a forward genetic screen is not predicated on any specific cell type or mechanism. That said, once a candidate gene is identified in a forward screen, follow-up work is necessary to confirm the involvement of that gene, including a definition of its cell type of action. These validation studies almost invariably involve reverse genetic approaches such as Cre/lox.

Additional methods have been developed for manipulation of gene expression in cardiomyocytes. Like Cre, transgenic mouse lines have been generated to express a tetracycline-responsive transcriptional transactivator activator (tTA) from a cardiomyocyte-specific promoter, such as Myh6 (92, 93). These mice are then bred with lines engineered with tetracycline operator (tetO) sites linked to genes of interest to achieve doxycycline (dox)-dependent changes in gene expression. An advantage of this approach is that it is possible to inactivate dox-dependent changes in gene expression with drug administration, which is not possible with the irreversible Cre-mediated DNA recombination models. As an example, Myh6-tTA transgenic mice were used to transiently induce ErbB2-mediated cardiomyocyte proliferation after adult myocardial infarction without inducing cardiomegaly in mice (11). An important caveat to recognize is that similar to Cre, overexpression of tTA on its own can affect cardiac gene expression and function (94), thus inclusion of all appropriate controls is essential for studies using these mice. An alternative method for altering gene expression specifically in cardiomyocytes is by infection with AAV9. This approach is increasingly used for induced expression of cardioproliferative or protective proteins, usually under the control of a sarcomeric protein regulatory element such as troponin T, and has the added advantage of not requiring transgenic modifications so it can be used for gene therapy in a variety of mammals, potentially including humans (95).

Summary.

In the case of cardiomyocyte-specific Cre driver lines, Cre-positive controls are highly recommended to ensure that any measurable differences to cell-cycle activation and cardiac function are due to the gene of interest and not off-target effects of Cre-recombinase. Furthermore, single-allele (i.e., hemizygous or heterozygous) experimental animals are recommended to avoid excessive Cre expression. If Cre-positive and Cre-negative animals are compared, the data should be cautiously interpreted keeping in mind the possibility that observed phenotypes may have been impacted by Cre expression, rather than solely by manipulation of the gene of interest. Although tamoxifen-inducible approaches lessen concern, it remains necessary to minimize the dose and frequency of tamoxifen administration (46) and to avoid data acquisition until the acute effects of Cre have subsided (79). We recommend applying these concerns when using Cre drivers specific to other cell types. Furthermore, for any investigation using alternative recombinases or tTA, it would be prudent to control for the effect of the driver as described earlier for Cre. To control for the influence of strain background, control and experimental mice should ideally be on a consistent and defined strain background. If this is not possible or practical, advisable practices include using littermate mice rather than only age-matched mice and using a sufficient number of mice to overcome the effects of strain background variation. Reporting on strain background in methods sections of publications should also be standard practice.

ASSESSMENT OF CARDIOMYOCYTE PROLIFERATIVE ACTIVITY IN PORCINE (PRECLINICAL) AND HUMAN (CLINICAL) HEARTS

Although genetically manipulated lines and tracking tools have enhanced rigorous assessment of cardiomyocyte proliferative activity in mice, these approaches are not widely available for large animal models and are not feasible in clinical studies of human heart regeneration. Despite these limitations, many of the histological, morphological, and stereological approaches described earlier have been used to identify cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activity in porcine and human hearts, apart from the genetic manipulations to assess definitive cytokinesis.

Porcine cardiomyocytes are very different from those of humans or mice in the number of nuclei, with up to 32 per cardiomyocyte, and prolonged period of endoreplication several months after birth (27) (Fig. 1). Proliferating cardiomyocytes in regenerating neonatal pig hearts were identified by combinations of cTnT immunostaining of striated cells, along with detection of Ki67, AKB, thymidine analog incorporation, and Nkx2.5 nuclear expression (96, 97). Limitations of these approaches include the lack of myocyte specificity, potential downregulation of Nkx2.5 expression during cardiomyocyte maturation, and transience of AKB activity. Similarly, induction of cardiomyocyte cell cycling by AAV delivery of microRNA therapy or knockdown of Hippo signaling in adult pigs after ischemic injury was assessed by combinations of BrdU/EdU incorporation, pHH3 expression, and AKB localization, together with sarcomeric protein expression and delimitation of cell borders by WGA staining (51, 98). As described earlier, the accuracy of assigning proliferative nuclei to cardiomyocytes can be enhanced by analysis of three-dimensional reconstructions of confocal z-stack images of obviously striated cells. In general, combining multiple assays for determination of cardiomyocyte cell cycling is standard for evaluation of repair or renewal of cardiomyocytes in pigs. However, multinucleation of porcine cardiomyocytes makes it even more challenging to distinguish endoreplication from true proliferation and generation of de novo cardiomyocytes, especially in the complex setting of adult ischemic injury.

Access to human cardiomyocytes for assessment of regeneration and repair mechanisms in vivo is limited. This is illustrated by an initial report of cardiac regenerative repair in a human infant born with a myocardial infarction with significantly improved cardiac function after antithrombotic therapy (99). The authors suggest that regenerative repair may have occurred based on the improved cardiac function, but direct assessment of cardiomyocyte proliferative activity or cell numbers was not possible in a living infant. Evidence for human cardiomyocyte cell cycling has been obtained from studies of human heart tissue by direct assessment of cell-cycle markers on histological sections (100) and by calculating cardiomyocyte nuclear turnover in myocardial samples from individuals exposed to 14C radiation with nuclear bomb tests (3). In the latter example, cardiomyocyte nuclei were isolated by nuclear flow sorting using cardiac Troponin T and I antibodies (3). Use of Pcm1 in the cell sorting protocol has further improved the identification of cycling cardiomyocytes from human cardiac tissue explants (47). Populations of cardiomyocyte nuclei were then analyzed by mass spectrometry for retention of 14C (3). Prospective in vivo labeling of DNA synthesized in S-phase human cardiomyocytes has been achieved by administration of 15N-thymidine to an infant with tetralogy of Fallot (62, 101). In these studies, cardiomyocytes were identified based on the presence of striated sarcomeres in multiple-isotope imaging mass spectrometry (MIMS) together with assessment of nucleation in isolated individual α-actinin striated cardiomyocytes from cardiac muscle biopsies. Although there are limitations with both techniques, the use of two independent assessments of cardiomyocyte nuclear division reinforces conclusions related to cardiomyocyte cell cycling in human tissue samples.

DISCUSSION

Heart regeneration is a rapidly expanding field. The possibility of stimulating pre-existing cardiomyocytes to re-enter the cell cycle and undergo bona fide proliferation to promote myocardial remuscularization is regarded as scientifically feasible by many investigators. However, as our knowledge increases surrounding the shortfalls of various experimental methodologies used to interrogate cardiomyocyte cell biology, experimental rigor must accordingly increase. For example, because we now know that Cre recombinase, in addition to causing DNA damage and cardiac dysfunction, can induce transient re-entry of cardiomyocytes into the cell cycle in certain conditions, rigorous controls are warranted to ensure that off-target effects of Cre do not obfuscate experimental findings. Also, it must be appreciated that assessing the proliferation of cardiomyocytes, in comparison with cell types that undergo conventional mitosis, is relatively nonstraightforward, therefore demanding the inclusion of additional precision and metrics to ensure that appropriate conclusions are drawn. In this review, we have highlighted several areas that would benefit from the adoption of experimental standards and have accordingly offered our collective recommendations regarding how these standards might be satisfied using currently available tools (Table 4). Nonetheless, our commentary should not imply a requirement for the recommended tools and methods to be used in each study; however, we do recommend caution when drawing conclusions and suggest utilization of multiple strategies to back a claim when possible, keeping in mind that it is very difficult to prove that a cardiomyocyte has definitively proliferated, yielding two daughter cells. The limitations of each method must be recognized in the interest of “getting it right.”

Table 4.

Summary of experimental standards related to measuring cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration

| Experimental Standard | Best Practice(s) | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Identifying cardiomyocyte nuclei | 1) Stain for both sarcomere and nuclei when quantifying cell-cycle activation observed within the nucleus | 1) Sarcomere-only stains paired with confocal microscopy |

| 2) Use multiple strategies (i.e., ≥2 cardiomyocyte and cell-cycle antigen pairings) when drawing a conclusion | ||

| 3) Remain cognizant of marker specificity as new data are released | ||

| Distinguishing cell-cycle activation from proliferation | 1) Claim “proliferation” only if complete cell division has been assessed | 1) Only claim “cell-cycle activation” if complete cell division has not been assessed |

| 2) Quantification of traditional cytokinetic markers (e.g., Aurora kinase B, Anillin) are best paired with a second method | ||

| Assessing cardiomyocyte endowment | 1) Ideal methodology remains unclear | |

| 2) Additional caution is recommended when assessing cardiomyocyte numbers in the context of fibrotic injury | ||

| Controls when using genetically engineered models | 1) Littermate, single-allele, Cre-positive controls | 1) Practice extreme caution when comparing Cre-positive to Cre-negative animals |

| 2) Implement the above controls for alternative recombinases and regardless of targeted cell type | 2) If mixed genetic backgrounds are unavoidable, using littermates for controls is recommended. | |

| 3) Maintain lines on a defined genetic background and report background at time of publication |

It remains unknown if cardiomyocyte proliferation is required to remuscularize an injured heart. Alternatively stated, is cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activation sufficient to increase muscle mass perhaps through hypertrophic means? Certainly, some species are tolerant of high nuclear numbers (e.g., pigs), so it is not unreasonable to conclude that cell-cycle activation resulting in the addition nuclei or DNA content could be sufficient on its own to promote cardiac remuscularization and improved cardiac function following injury. On the other hand, high nuclear ploidy in humans correlates with heart disease and end stage heart failure (28, 102, 103). Thus, cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis in this context could be indicative of adverse remodeling and not remuscularization. It is clear that some degree of polyploidization and/or multinucleation are both natural and required for proper physiological growth; however, it remains unknown if polyploidization can reach consequential levels. Although these outstanding questions remain, we find it only more pertinent to carefully draw conclusions and delineate cell-cycle activation resulting in polyploidy versus true proliferation.

Additional questions that must be addressed regard the extent to which bona fide cardiomyocyte proliferation must occur to promote myocardial regeneration and functional recovery, and the extent to which proliferation can enhance outcomes without incurring cardiac dysmorphology, dysfunction, cardiomegaly, or potential rhabdomyoma. Studies to date have reported wide variability when quantifying cardiomyocytes in the border zone of infarcted murine adult hearts that re-enter the cell cycle, ranging from <0.5% to 25% of cardiomyocytes (2, 7, 8, 69, 104). Naturally, many of these seemingly disparate results could be due to differences in labeling and quantification strategies. Regardless, most agree that only a fraction of these cycling cells go on to divide (2, 7, 8, 69). A common argument, coming from both within and outside of the field, is that indications of only modest increases in cardiomyocyte proliferation following MI are unlikely to explain a positive outcome in cardiac output, thus additional factors are likely to be responsible if functional improvement has been observed. Furthermore, if experiments are improperly designed it can be difficult to discern protective versus proliferative benefits. On the other hand, it is also possible that, because cardiomyocytes must become at least transiently disconnected from the pseudosyncytium of the myocardium to proliferate, conduction and arrhythmogenic abnormalities may develop. Thus, too many cardiomyocytes re-entering a proliferative state simultaneously, or a recently divided cardiomyocyte failing to reintegrate following dedifferentiation and proliferation, could also be consequential to the system. These are complex questions that await experimental resolution.

Importantly, this review focuses on assessing cardiomyocyte proliferation in mammalian models, although we recognize that stimulating cardiomyocyte renewal is just one component required for accomplishing successful heart regeneration. Cardiac regeneration is a complex process facilitated by multiple cellular processes, including angiogenesis (105–107), immune response (105, 108, 109), lymphatic function (104), and scar resolution (110) or altered scar organization (107), among others. Several new technologies, including single-cell RNA sequencing (33, 72, 111), spatial transcriptomics (112, 113), and single-cell proteomics (114, 115), are likely to help us better understand the distinct cellular profiles of cardiomyocyte subpopulations and the intricacies of cardiac regeneration. Certainly, having a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of various cell types and molecular processes on cardiac regeneration will help us tailor therapeutic approaches aimed at achieving cardiac regeneration in adults.

GRANTS

This work was funded by American Heart Association Grants 18CDA34110240 (to M. Patterson), 18CDA34110053 (to L. Han), and 20TPA35500000 (to G. N. Huang); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01HL155085 (to M. Patterson), R21HL156022 (to M. Patterson and C. C. O’Meara), R01HL131788 (to J. Auchampach and J. W. Lough), R01HL133589 (to J. Auchampach), R01HL141159 (to C. C. O’Meara), R01HL138456 and R01HL160819 (to G. N. Huang), R01HL151386, R01HL151415, and R01HL155597 (to B. Kuhn), R01HL144938 (to H. M. Sucov), and R01HL135848 (to K. E. Yutzey); MCW Cardiovascular Center Grant FP00012308 (to J. Auchampach, J. W. Lough, and C. C. O’Meara); and Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment No. 5520561 (to C. C. O’Meara) and No. 5520519 (to L. Han).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.H., G.N.H., A.Y.P., H.M.S., K.E.Y., and M.P. prepared figures; J.A., L.H., G.N.H., B.K., J.W.L., C.C.O., A.Y.P., N.A.R., H.M.S., K.E.Y., and M.P. drafted manuscript; J.A., L.H., G.N.H., B.K., J.W.L., C.C.O., A.Y.P., N.A.R., H.M.S., K.E.Y., and M.P. edited and revised manuscript; J.A., L.H., G.N.H., B.K., J.W.L., C.C.O., A.Y.P., N.A.R., H.M.S., K.E.Y., and M.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nivedhitha Velayutham for constructive feedback on this manuscript and insights into the complexities of porcine cardiomyocytes. Figures have been created using stock images from BioRender (biorender.com) and Servier Medical Art (smart.servier.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Li Y, Lv Z, He L, Huang X, Zhang S, Zhao H, Pu W, Li Y, Yu W, Zhang L, Liu X, Liu K, Tang J, Tian X, Wang QD, Lui KO, Zhou B. Genetic tracing identifies early segregation of the cardiomyocyte and nonmyocyte lineages. Circ Res 125: 343–355, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL, Lechene CP, Lee RT. Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature 493: 433–436, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nature11682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabé-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisén J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324: 98–102, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Sadek HA. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science 331: 1078–1080, 2011. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drenckhahn JD, Schwarz QP, Gray S, Laskowski A, Kiriazis H, Ming Z, Harvey RP, Du XJ, Thorburn DR, Cox TC. Compensatory growth of healthy cardiac cells in the presence of diseased cells restores tissue homeostasis during heart development. Dev Cell 15: 521–533, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali SR, Hippenmeyer S, Saadat LV, Luo L, Weissman IL, Ardehali R. Existing cardiomyocytes generate cardiomyocytes at a low rate after birth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 8850–8855, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408233111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson M, Barske L, Van Handel B, Rau CD, Gan P, Sharma A, Parikh S, Denholtz M, Huang Y, Yamaguchi Y, Shen H, Allayee H, Crump JG, Force TI, Lien CL, Makita T, Lusis AJ, Kumar SR, Sucov HM. Frequency of mononuclear diploid cardiomyocytes underlies natural variation in heart regeneration. Nat Genet 49: 1346–1353, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ng.3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirose K, Payumo AY, Cutie S, Hoang A, Zhang H, Guyot R, Lunn D, Bigley RB, Yu H, Wang J, Smith M, Gillett E, Muroy SE, Schmid T, Wilson E, Field KA, Reeder DM, Maden M, Yartsev MM, Wolfgang MJ, Grützner F, Scanlan TS, Szweda LI, Buffenstein R, Hu G, Flamant F, Olgin JE, Huang GN. Evidence for hormonal control of heart regenerative capacity during endothermy acquisition. Science 364: 184–188, 2019. doi: 10.1126/science.aar2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B, Kühn B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell 138: 257–270, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aharonov A, Shakked A, Umansky KB, Savidor A, Genzelinakh A, Kain D, Lendengolts D, Revach OY, Morikawa Y, Dong J, Levin Y, Geiger B, Martin JF, Tzahor E. ERBB2 drives YAP activation and EMT-like processes during cardiac regeneration. Nat Cell Biol 22: 1346–1356, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-00588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Uva G, Aharonov A, Lauriola M, Kain D, Yahalom-Ronen Y, Carvalho S, Weisinger K, Bassat E, Rajchman D, Yifa O, Lysenko M, Konfino T, Hegesh J, Brenner O, Neeman M, Yarden Y, Leor J, Sarig R, Harvey RP, Tzahor E. ERBB2 triggers mammalian heart regeneration by promoting cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nat Cell Biol 17: 627–638, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncb3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Uva G, Tzahor E. The key roles of ERBB2 in cardiac regeneration. Cell Cycle 14: 2383–2384, 2015. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1063292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL, Martin JF. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science 332: 458–461, 2011. doi: 10.1126/science.1199010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flinn MA, Link BA, O'Meara CC. Upstream regulation of the Hippo-Yap pathway in cardiomyocyte regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol 100: 11–19, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leach JP, Heallen T, Zhang M, Rahmani M, Morikawa Y, Hill MC, Segura A, Willerson JT, Martin JF. Hippo pathway deficiency reverses systolic heart failure after infarction. Nature 550: 260–264, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature24045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng F, Xie B, Martin JF. Targeting the Hippo pathway in heart repair. Cardiovasc Res. 2021 Sep 16:cvab291. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvab291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monroe TO, Hill MC, Morikawa Y, Leach JP, Heallen T, Cao S, Krijger PHL, de Laat W, Wehrens XHT, Rodney GG, Martin JF. YAP partially reprograms chromatin accessibility to directly induce adult cardiogenesis in vivo. Dev Cell 48: 765–779 e7, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, Liu L, Conway SJ, Fu JD, Srivastava D. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature 485: 593–598, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inagawa K, Miyamoto K, Yamakawa H, Muraoka N, Sadahiro T, Umei T, Wada R, Katsumata Y, Kaneda R, Nakade K, Kurihara C, Obata Y, Miyake K, Fukuda K, Ieda M. Induction of cardiomyocyte-like cells in infarct hearts by gene transfer of Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5. Circ Res 111: 1147–1156, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.271148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohamed TM, Stone NR, Berry EC, Radzinsky E, Huang Y, Pratt K, Ang YS, Yu P, Wang H, Tang S, Magnitsky S, Ding S, Ivey KN, Srivastava D. Chemical enhancement of in vitro and in vivo direct cardiac reprogramming. Circulation 135: 978–995, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong JJ, Yang X, Don CW, Minami E, Liu YW, Weyers JJ, Mahoney WM, Van Biber B, Cook SM, Palpant NJ, Gantz JA, Fugate JA, Muskheli V, Gough GM, Vogel KW, Astley CA, Hotchkiss CE, Baldessari A, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Gill EA, Nelson V, Kiem HP, Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature 510: 273–277, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engel FB, Schebesta M, Keating MT. Anillin localization defect in cardiomyocyte binucleation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 601–612, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]