Abstract

Cell signaling mediated by the KIT receptor is critical for many aspects of oogenesis including the proliferation and migration of primordial germ cells, as well as the survival, growth, and maturation of ovarian follicles. We previously showed that KIT regulates cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation, and in this study, have investigated the mechanisms downstream of the receptor by modulating the activity of two downstream signaling cascades: the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. E17.5 ovaries were cultured for 5 days with a daily dose of media supplemented with either the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, the MEK inhibitor U0126, or a DMSO vehicle control. Our histological observations aligned with the established role of PI3K in oocyte growth and primordial follicle activation but also revealed that LY294002 treatment delayed the processes of cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. U0126 treatment also led to a reduction in oocyte growth and follicle development but did not appear to affect cyst breakdown. The delay in cyst breakdown was mitigated when ovaries were dually dosed with LY294002 and KITL, suggesting that while KIT may signal through PI3K to promote cyst breakdown, other signaling networks downstream of the receptor could compensate. These observations unearth a role for PI3K signaling in the establishment of the ovarian reserve and suggest that PI3K might be the primary mediator of KIT-induced cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation in the mouse ovary.

Keywords: primordial follicle formation, cyst breakdown, PI3K signaling, oocyte growth

PI3K signaling promotes cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation in mice.

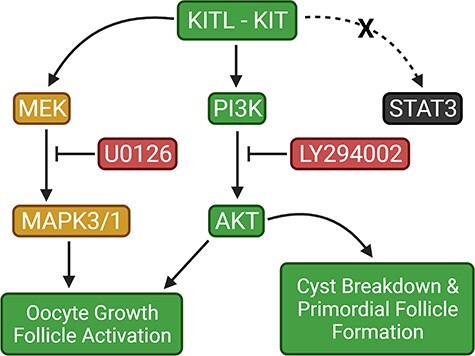

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

The reproductive potential of a mammalian female is fundamentally dependent on the number and quality of primordial follicles that comprise the ovarian reserve—the source of all “eggs”. Consequently, the developmental programs that modulate oogenesis must be tightly regulated to ensure that fertility is not compromised. At around embryonic day 7 (E7) in the mouse, a small cohort of epiblast cells receive inductive signals that specify them to a primordial germ cell fate [1–5]. These nascent PGCs migrate via the hindgut and dorsal mesentery to arrive at the genital ridges at around E10.5, where they proliferate rapidly by mitosis to colonize the developing gonads as oogonia or spermatogonia while somatic sex determination takes place [6, 7]. As PGCs proliferate from E10.5 to E13.5, they remain connected by intercellular bridges resulting from incomplete cytokinesis, producing clusters or “cysts” of synchronously developing cells [8]. Cysts consist of up to 30 cells, which can also fragment into smaller cysts and associate with cysts from unrelated progenitors to form a germ cell nest in which some cells are not connected by intercellular bridges [8–10]. After mitotic divisions cease at E13.5, germ cells enter meiosis and are called oocytes. Subsequently, oocytes become separated from each other by a process called cyst breakdown and assemble into primordial follicles consisting of an individual oocyte surrounded by a monolayer of somatic pregranulosa cells. A wave of development ensues among the first set of primordial follicles to form, however most remain dormant until stimulated by hormones during puberty. Cyst breakdown involves a substantial depletion of the oocyte population with only about 20%–30% of oocytes surviving [9, 11, 12]. The progression of these events is crucial to normative fecundity, but much remains unknown about the coordinated cell signaling pathways that regulate cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation.

KIT signaling is known to promote cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation in a variety of processes including gametogenesis, melanogenesis, and hemopoiesis [13, 14]. The transmembrane receptor, KIT, and its ligand KITL or stem cell factor (SCF), are encoded by the murine White spotting (W) and Steel (Sl) loci, respectively [15–20]. Loss of KIT function in W or Sl mutants impairs PGC migration and proliferation, and affects the growth of ovarian follicles [21–23]. In vitro experiments have also shown that KITL supplementation promotes normal survival, proliferation, and migration of PGCs in culture, and acts to suppress apoptosis [24–27]. Mutant Slpan mice produce minuscule quantities of KITL, have a depleted pool of primordial follicles as neonates, and display an almost total obstruction of the primordial to primary follicle transition [23]. Accordingly, the pool of primordial follicles is unable to develop, resulting in mice that are sterile. Similarly, by 2 weeks of age, folliculogenesis is impeded in female mice injected with the KIT function-blocking antibody ACK2 as neonates [28]. Previous work from our lab has shown that both KIT and KITL are highly expressed during the perinatal window in which cyst breakdown and follicle formation occur most appreciably [29]. Furthermore, we have observed that ACK2-mediated KIT inhibition in mouse ovary organ culture reduces cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation, while both processes are promoted by KITL supplementation [29]. Comparably, fetal hamster ovaries cultured with KITL show increased cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation [30]. In rats, use of the anticancer agent imatinib mesylate, an inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as KIT, causes delayed cyst breakdown, follicle assembly, and activation of the primordial follicle pool [31]. The survival and maturation of activated follicles are also influenced by the expression of KIT and KITL [28, 32–34].

KIT can activate several intracellular signal transduction cascades including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and the janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathways [35, 36]. Accordingly, intrafollicular communication between the oocyte and encompassing granulosa cells can be facilitated to elicit the appropriate growth or developmental process. Notably, several studies have shown that KIT-mediated activation of the PI3K pathway and its downstream effectors leads to the onset of oocyte growth and primordial follicle activation and development [37–41]. The MAPK pathway has been implicated in primordial follicle activation through mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-KITL signaling in granulosa cells, upstream of KIT-PI3K signaling in oocytes [42]. Recent work has also elucidated the role of the JAK/STAT pathway and its downstream targets in germ cell cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation [43, 44]. However, it remains unclear whether KIT-induced cyst breakdown and primordial follicle assembly occurs through these pathways.

Based on our previous work we postulated that KIT influences the formation of the ovarian reserve through regulation of the MAPK pathway [29]. In the current study, we used the ovary organ culture technique to examine whether the JAK/STAT, PI3K, and MAPK cascades are activated by KITL supplementation, to determine whether their pharmacological inhibition affects cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation, and also whether those effects are specifically mediated by KIT. Our results indicate that both PI3K and MAPK signaling promote oocyte growth and follicle development in mice, but that signaling through PI3K also regulates cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

All animal protocols and experimental procedures complied with ethical regulations and were approved by the Syracuse University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animals

Adult C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, and housed at a controlled photoperiod (14 h light, 10 h dark), temperature (21–22°C), and humidity with food and water available ad libitum. Adults were bred using timed matings, and females were examined the following morning for the presence of a vaginal plug which was considered E0.5. Pregnant mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation for fetal ovary collection at E17.5. Otherwise, pregnant mice usually gave birth at 19.5 days postcoitum (postnatal Day 1 (PND 1)). For postnatal ovary collection, pups were euthanized by decapitation on PND 3.

Mouse ovary organ culture

Ovaries were dissected and cleaned in cold HBSS (Gibco), then gently placed on 0.4 μm, 30 mm diameter Millicell inserts (Millipore) in a 6-well culture plate on ice. Inserts were transferred to a new 6-well plate with 1.3 mL of prewarmed 37°C media consisting of DMEM/F12 (1: 1) (Gibco), 1 mg/mL BSA (Gibco), 1 mg/mL Albumax (Gibco), 0.05 mg/mL L-ascorbic acid (Sigma), 5X ITS-X (Gibco), and penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) prior to incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2. A single drop of media was placed on each ovary to prevent them from drying out. For 5-day cultures, ovaries were given a minimum of 30 min to equilibrate before dosing with control or treatment media. Ovaries cultured for immunoblotting experiments were allowed to equilibrate for 6 h. When testing for signaling pathway activation in response to supplementation with KITL, recombinant SCF (R&D Systems) was delivered in media consisting of DMEM/F12 (1:1) (Gibco) and penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) only. Depending on the duration of culture, ovaries were either given a single dose, or a daily dose of media supplemented with recombinant SCF (R&D Systems) at 100 ng/mL, 10 μM of the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Cell Signaling) or 25 μM of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Cell Signaling). Comparable doses of each inhibitor have been effectively used in mouse and rat ovary culture, and cytotoxic effects were not reported. Inhibitors were reconstituted with DMSO, which was also used at the same final concentration in media as a vehicle control. Both ovaries from a single mouse were never paired into the same condition.

Antibodies

For immunohistochemistry, Anti-DDX4/MVH (VASA) antibody (Abcam) was used at a dilution of 1:250 while the goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used at a dilution of 1:200. For western blotting, p44/42 MAPK and phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204) antibodies (Cell Signaling) were used at a dilution of 1:2000 and 1:1000, respectively. Anti-AKT1 + AKT2 + AKT3 [EPR16798] and Anti-AKT1 (phospho S473) [EP2109Y] antibodies (Abcam) were used at a dilution of 1:20 000 and 1:5000, respectively. Stat3 (C-20) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Anti-STAT3 (phospho Y705) [EP2147Y] antibody (Abcam) were each used at a dilution of 1:2000. Goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP linked secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used at a dilution of 1:2000 for phosphorylated targets and 1:15 000 when probing for total protein. Mouse GAPDH (Abcam) was used at a dilution of 1:2000. Goat anti-mouse IgG HRP linked secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used at a dilution of 1:10 000 (see Tables 1 and 2 for additional details on antibodies used).

Table 1.

Primary antibodies and dilutions used

| Antibody name/target antigen | Vendor | Catalog # | Host organism | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKT1 + AKT2 + AKT3 | Abcam | ab179463 RRID: AB_2810977 | Rabbit | 1:20 000 |

| GAPDH | Abcam | ab125247 RRID: AB_11129118 | Mouse | 1:2000 |

| MAPK (Erk1/2) | Cell signaling | 4695 RRID: AB_390779 | Rabbit | 1:2000 |

| STAT3 (C-20) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-482 RRID: AB_632440 | Rabbit | 1:2000 |

| AKT1 (phospho S473) | Abcam | ab215873 RRID: AB_2224551 | Rabbit | 1:5000 |

| MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) | Cell signaling | 4376 RRID: AB_331772 | Rabbit | 1:1000 |

| STAT3 (phospho Y705) | Abcam | ab76315 RRID: AB_1658549 | Rabbit | 1:2000 |

| VASA | Abcam | ab13840 RRID: AB_443012 | Rabbit | 1:250 |

Table 2.

Secondary antibodies and dilutions used

| Antibody name/target antigen | Vendor | Catalog # | Host organism | Dilution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-11008 RRID: AB_143165 | Goat | 1:200 | |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 31460 RRID: AB_228341 | Goat | 1:2000, 1:15 000 | |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 31430 RRID: AB_228307 | Goat | 1:10 000 |

Immunohistochemistry

Ovaries were fixed with 5.3% EM grade paraformaldehyde in PBS for at least 1 h, then washed several times at room temperature in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (PT). Ovaries were then incubated with PT + 5% BSA for at least 30 min at room temperature, before incubation with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The following day, ovaries were washed in PT + 1% BSA, treated with 0.1 mg/mL RNase A, labeled with 5 μg/mL propidium iodide, then incubated with the preabsorbed secondary antibody overnight at 4°C. Finally, ovaries were washed with PT + 1% BSA, rinsed with PBS, mounted on coverslips with a drop of Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and observed on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Confocal imaging

Each ovary was assigned 2 randomly selected cores for visualization. A core consists of 4 optical sections that are 212 × 212 μm and are each separated by a depth of 15–20 μm. The 4 optical sections span both the cortex and medulla to ensure that all regions of the ovary are assessed. For each ovary, 2 cores with 4 optical sections were visualized for a total of 8 sections. A z-stack of images was taken for each optical section. Z-stacks consisted of 5 images both above and below the optical section with a 1 μm separation. Zen software (Zeiss) was used for imaging and subsequent analysis of the ovaries.

Analysis of oocyte numbers, cyst breakdown, and follicle development

For each ovary, oocytes in each of the 8 optical sections were counted, then the numbers averaged across ovaries and reported as the number of oocytes per section. The proportion of the total number of oocytes in cysts was determined by examining the z-stacks to see whether each oocyte in the center image was touching or sharing cytoplasm with another oocyte either in, above, or below the plane of focus. Cyst breakdown was evaluated as the proportion of the total number of oocytes that were not in a germ cell cyst and was reported as percent single oocytes. Follicle development was determined by counting the number of primordial, transitional, and primary follicles present, and reported as percent primordial and developing.

Analysis of oocyte growth

The diameter of oocytes in each optical section was measured in micrometers by drawing a line across the widest region of the cell. Only oocytes with distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic staining that were fully within the field of view were included. Ovary measurements were pooled together and reported as average oocyte diameter per ovary.

Western blotting

Whole ovaries were dissected in cold HBSS and collected in TBS after culture before homogenization in an extraction buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% SDS. 5 mM EDTA and 1× Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added just prior to lysis. Ovaries were manually homogenized in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube using an RNase-free pestle and 10 μL of buffer per ovary. Lysates were collected after centrifugation at 15 000 rpm for 10 min, and protein concentrations were estimated using a BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a FilterMax™ F5 multimode microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Lysates were run on 10% polyacrylamide gels (BioRad) in Tris-Glycine-SDS running buffer then electroblotted onto Immobilon P PVDF membranes (Millipore) that had been activated for 1 min in 100% methanol followed by 5 min each in dH2O and Tris-Glycine transfer buffer. Membranes were rinsed with TBS + 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) then blocked in TBST +5% BSA for at least 30 min at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then cut laterally across the 75 kDa and 50 kDa regions so that samples could be probed for multiple targets. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer, and incubations were done overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies were also diluted in blocking buffer, and incubations were done at room temperature for 1 h. Bands were visualized using SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

All experiments are representative of at least 3 independent replicates, and data values are presented as means ± SEM. Unpaired, two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction or the one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were used to determine significant differences between control and treatment groups. Grubbs’ test was used to identify outliers based on oocyte number. The Anderson–Darling test was used to verify that percentage data are normally distributed. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 Software. For all results, P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

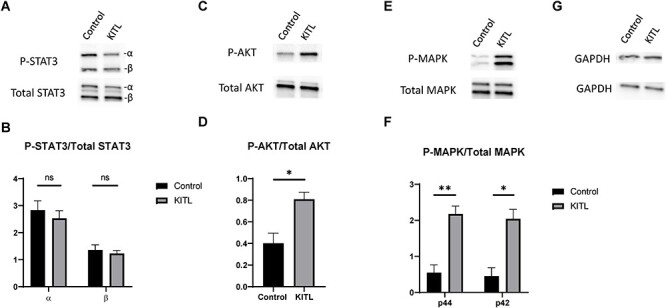

KIT activates AKT and MAPK3/1, but not STAT3

In the first set of experiments, we examined several of the signaling pathways downstream of KIT that could be involved in cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. PND 3 ovaries were harvested and equilibrated to culture conditions for 6 h, then dosed with recombinant KITL for 5 min. Whole ovary extracts were prepared for western blotting, and probed for total STAT3, AKT, and MAPK3/1 as well as the phosphorylated forms of these proteins (Figure 1). Total protein levels of STAT3 (Figure 1A), AKT (Figure 1C), and MAPK3/1 (Figure 1E) remained comparable between control and KITL-treated ovaries. However, although phosphorylated STAT3 levels were not significantly affected by KITL treatment (Figure 1B), phosphorylation of AKT increased two-fold (Figure 1D) and phosphorylated MAPK3/1 levels increased more than three-fold (Figure 1F). These observations confirm that KIT can signal via both AKT and MAPK3/1 and suggest that KIT-mediated AKT or MAPK3/1 activation could be a part of the coordinated cell signaling process that regulates oocyte cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation in the mouse ovary.

Figure 1.

KITL supplementation induces phosphorylation of AKT and MAPK3/1, but not STAT3. PND 3 ovaries were cultured in media supplemented with KITL for 5 min then extracts were prepared for western blotting and probed for total and phosphorylated STAT3 (A), AKT (C), MAPK3/1 (E), and reprobed for GAPDH as a loading control (G). Signal intensity ratios of phosphorylated to total protein are also shown for STAT3 (B), AKT (D), and MAPK3/1 (F) and are representative of 3 experimental replicates. Data presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between groups (t-test, ns denotes P > 0.05, * denotes P < 0.05, ** denotes P < 0.01).

AKT and MAPK3/1 promote oocyte growth

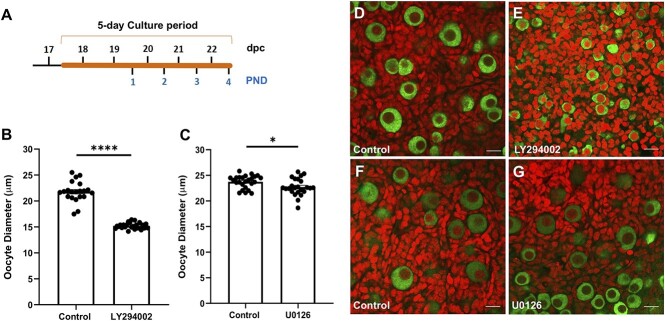

Multiple studies have demonstrated that KIT-KITL signaling, PI3K-AKT signaling, and MAPK3/1 signaling regulate the growth of primordial germ cells, as well as postnatal oocyte growth during the process of primordial follicle activation and subsequent stages of folliculogenesis [23, 36, 37, 41, 42, 45–47]. To confirm the efficacy of pathway inhibitors in our culture system at the selected dose, we tested whether LY294002 (a PI3K inhibitor) and U0126 (a MEK inhibitor) treatment affected oocyte growth during the perinatal period of substantial cyst breakdown. Ovaries were harvested at E17.5 and cultured for 5 days in media supplemented with either 25 μM LY294002 or 10 μM U0126 whereas control ovaries were cultured in media with DMSO as a vehicle control at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.05%, respectively (n = 21–25 ovaries per group). At the end of culture, ovaries were the equivalent of PND 4 (Figure 2A) and were immunolabeled using an antibody to the germ cell marker VASA, and the nuclear marker propidium iodide, to facilitate confocal imaging and histological assessment (Figure 2D–G). Congruent with previously reported observations, we noticed growth restrictions in both sets of treated ovaries. Oocytes in ovaries treated with LY294002 were significantly smaller than those in the control cohort with average diameters of 15.21 μm and 21.78 μm, respectively (Figure 2B). The growth restriction due to MEK inhibition was much less severe, with oocytes having an average diameter of 22.71 μm, whereas control ovaries had oocytes averaging 23.74 μm in size (Figure 2C). We also confirmed by immunoblotting experiments that phosphorylation levels of AKT and MAPK3/1 were significantly reduced after being treated with LY294002 or U0126 for 2 h (Supplementary Figure 1A–D). These results align with previous reports, but also indicate that AKT and MAPK3/1 affect oocyte growth during primordial follicle formation.

Figure 2.

PI3K and MAPK3/1 signaling affect oocyte growth during the perinatal window of cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. (A) Timeline showing the 5 day culture scheme. (B) Oocyte diameter measurements for LY294002 treatment and (C) U0126 treatment. Data presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 21–25 ovaries per group. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between groups (t-test, * denotes P < 0.05, **** denotes P < 0.0001). (D–G) Confocal sections from control and treated ovaries labeled for VASA (green) to visualize oocytes and propidium iodide (red) to visualize nuclei. Scale bar, 20 μm.

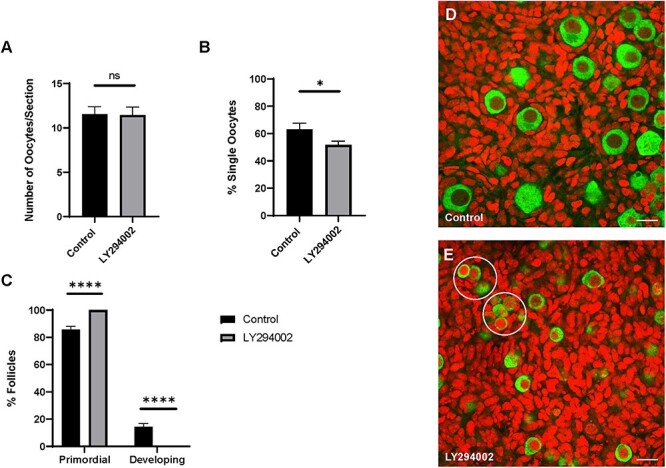

Inhibition of PI3K reduces cyst breakdown and delays follicle development

In mice, cyst breakdown occurs most appreciably from E17.5 to PND 5, but the molecular mechanisms controlling these processes are only partly known [44, 48–52]. Given our previous observations that both KIT and KITL are highly expressed during this time [29] and that KIT can induce AKT activation (Fig. 1C and D) we decided to test whether PI3K signaling is involved in cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. Ovaries from mice at E17.5 were cultured for 5 days in control media or treated with LY294002, and we assessed oocyte survival, cyst breakdown and follicle development (Figure 3). Interestingly, we noticed that a significantly higher proportion of oocytes in ovaries treated with LY294002 remained in cysts. As shown in Figure 3B, 63% of oocytes in control ovaries had formed follicles while PI3K inhibition restricted that to about 52%. Surprisingly, oocyte numbers were comparable between control and LY294002 treated ovaries with an average of about 11 oocytes per optical section analyzed (Figure 3A). Consistent with the established role of PI3K signaling in follicle development [53, 54] we noticed that in treated ovaries, all follicles appeared to be arrested at the primordial stage while at least 14% of follicles in control ovaries had already begun developing with granulosa cell morphology shifting from squamous to cuboidal (Fig. 3C–E).

Figure 3.

PI3K signaling promotes cyst breakdown. (A) Number of oocytes, (B) percent single oocytes and (C) percent primordial or developing follicles per ovary. Data presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 21 ovaries (control) and 24 ovaries (LY294002). Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between groups (t-test, ns denotes P > 0.05, * denotes P < 0.05, **** denotes P < 0.0001). (D–E) Confocal sections from control and treated ovaries labeled for VASA (green) to visualize oocytes and propidium iodide (red) to visualize nuclei. Scale bar, 20 μm. Oocyte clusters in (E) are encircled.

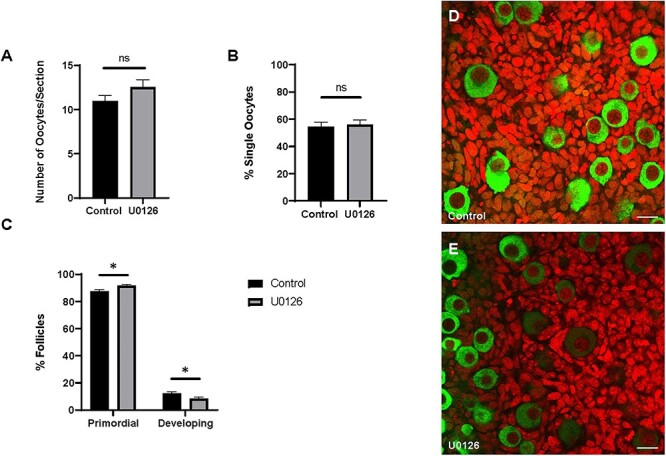

Inhibition of MAPK3/1 reduces follicle development

MAPK8, MAPK9, and MAPK10, members of the JNK subfamily of MAPKs, have recently been implicated in mouse primordial follicle formation [52]. Therefore, we wanted to explore whether members of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase subfamily are also involved to more holistically capture the role of the MAPK pathway in the ovary. Since we observed that KITL supplementation increases MAPK3/1 activation, we decided to also test for a possible role in cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. Ovaries were harvested from mice at E17.5 and cultured for 5 days in control media or treated with U0126. We noticed that oocyte survival was comparable between conditions (Figure 4A), and also found that a similar proportion of oocytes in control and treated ovaries were in cysts (Figure 4B). As shown in Figure 4B, 54.41% of oocytes in control ovaries were assembled in follicles compared to 56.05% in U0126 treated ovaries. In congruence with data implicating MAPK3/1 in follicle development [42, 55, 56], we observed a delay in follicle development due to U0126 treatment. In control ovaries, 12.35% of follicles had initiated development beyond the primordial stage, whereas only 8.39% of follicles in U0126 treated ovaries had begun developing (Figure 4C–E).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of MAPK3/1 signaling does not affect cyst breakdown. (A) Number of oocytes, (B) percent single oocytes, and (C) percent primordial or developing or follicles per ovary. Data presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 25 ovaries (control) and 24 ovaries (U0126). Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between groups (t-test, ns denotes P > 0.05, * denotes P < 0.05). (D–E) Confocal sections from control and treated ovaries labeled for VASA (green) to visualize oocytes and propidium iodide (red) to visualize nuclei. Scale bar, 20 μm.

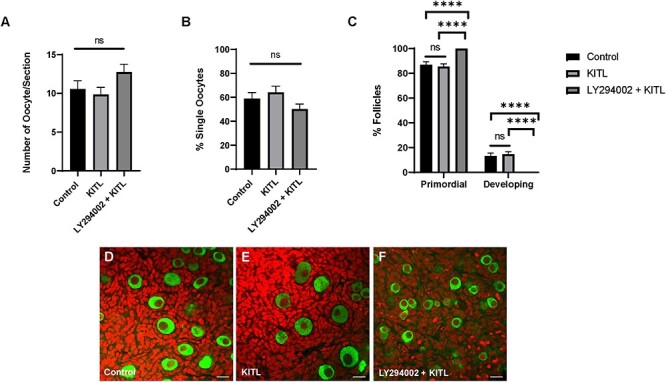

KIT-mediated cyst breakdown may not be exclusively transduced via PI3K

Based on our previous work showing that KIT regulates cyst breakdown [29] and our current observations that PI3K also promotes cyst breakdown (Figure 3B), we wanted to establish whether KIT-mediated PI3K-AKT signaling is part of the coordinated regulatory mechanism of primordial follicle formation. Firstly, we confirmed that KIT-induced AKT activation occurs specifically through PI3K and not through other signaling molecules downstream of the receptor (Supplementary Figure 2). PND 3 ovaries were harvested and equilibrated to culture conditions for 6 h or pretreated with LY294002 for 6 h, then dosed with recombinant KITL for 5 min. Whole ovary extracts were probed for total AKT and phosphorylated AKT. Total protein levels of AKT were comparable between control, KITL, and LY294002 + KITL-treated ovaries while phosphorylated AKT levels were significantly depleted in ovaries pretreated with LY294002 prior to KITL supplementation (Supplementary Figure 2A and B). These observations suggest that KIT-mediated AKT activation occurs specifically via PI3K and not through any other signaling molecules downstream of the receptor. To examine whether KIT-PI3K-AKT signaling specifically regulates cyst breakdown, we harvested ovaries from mice at E17.5 and cultured them for 5 days in control media, media supplemented with KITL, or a combination of LY294002 and KITL. We reasoned that if KIT regulated cyst breakdown via a signaling pathway other than PI3K, then KITL supplementation would rescue the effects of LY294002 on cyst breakdown. We first verified that KITL supplementation did not rescue the oocyte growth defect due to PI3K inhibition (Figure 5D–F). Although control ovaries had an average oocyte diameter of 22.26 μm, ovaries supplemented with KITL had an average oocyte diameter to 23.16 μm but the dual dosage of LY294002 + KITL resulted in a similar growth restriction to LY294002 treatment alone with oocytes averaging 15.90 μm in diameter (Supplementary Figure 2C). We observed similarities in oocyte number between conditions. As shown in Figure 5A there were nearly 13 oocytes per optical section in ovaries dually dosed with LY294002 and KITL compared to fewer than 11 oocytes in both control and KITL-treated ovaries. Interestingly, the delay in cyst breakdown was mitigated when ovaries were dually dosed with LY294002 and KITL. As shown in Figure 5B, 50.13% of oocytes were assembled in follicles in the LY294002 + KITL condition compared to 58.94% in control ovaries and 64.08% in ovaries dosed with KITL. The progression of follicle development was comparable between control and KITL-treated ovaries, but all follicles appeared to be arrested at the primordial stage in the LY294002 + KITL cohort (Figure 5C–F). These results suggest that KIT-PI3K signaling plays a role in regulating cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation but that there could also be other downstream signaling pathways involved since the delay in cyst breakdown was mitigated in comparison to LY294002 treatment alone.

Figure 5.

KITL supplementation mitigates the delay in cyst breakdown due to LY294002 treatment. (A) Number of oocytes, (B) percent single oocytes, and (C) percent primordial or developing follicles per ovary. Data presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 17 ovaries (control), 20 ovaries (KITL) and 17 ovaries (LY294002 + KITL). Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between groups (ANOVA, ns denotes P > 0.05, **** denotes P < 0.0001). (D–F) Confocal sections from control and treated ovaries labelled for VASA (green) to visualize oocytes and propidium iodide (red) to visualize nuclei. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

Establishment of the primordial follicle pool and the subsequent development of these follicles is essential for ovarian function. Disruptions in these processes could adversely affect fertility or reproductive life span. Several studies in the last decade have demonstrated roles for KIT in the regulation of cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation [29, 31], but the specific downstream signaling pathway(s) are yet to be elucidated. In the present study, we used in vitro culture methods to analyze the roles of signaling pathways downstream of KIT at the time when the ovarian reserve is being established. Based on our previous work, we hypothesized that KIT signals through MAPK3/1 to regulate cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation.

In alignment with but adding to previous reports, we found that KITL supplementation increased the phosphorylation levels of both AKT and MAPK3/1 [29, 38]. In the study by Jones and Pepling, E17.5 ovaries were dosed with KITL at 24 h intervals over 3 days. It is possible that the precise stimulation of kinase activation by KITL would not be sustained and accurately measurable over a 24-hour period or there could be overlap between other signaling pathways that could activate STAT3, AKT, or MAPK3/1. Additionally, Reddy et al. isolated mouse oocytes at PND 8 and stimulated them with KITL for various time periods ranging from 2 min to 60 min. They found that the KITL-mediated induction of p-AKT was transitory, as phosphorylation levels fell between 5 min and 60 min. Also, they did not observe induction of p-MAPK3/1 due to KITL supplementation. However, the study by Reddy et al. is beyond of the perinatal window of substantial cyst breakdown, and the oocyte specific culture would not capture the signaling interactions taking place in granulosa cells as follicles form. Therefore, our results demonstrate that p-AKT and p-MAPK3/1 can be induced by KIT during cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation.

The JAK/STAT pathway has recently been implicated in cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation [43, 44, 57] but the identity of the upstream receptor remains unclear. Based on our findings, we deduce that JAK/STAT signaling in primordial follicle formation may be activated independently of KIT. However, we measured activation of this pathway by specifically testing for induction of p-STAT3 since it is known to be highly expressed in oocytes, is essential for the early development of mouse embryos, and was recently implicated in cyst breakdown and follicle formation [43, 58]. It may be possible that any of the JAK family members, JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, or TYK2, or any of the other 6 STAT proteins could be activated by KIT. The study by Huang et al. showed that JAK2 and JAK3 regulate cyst breakdown by influencing oocyte survival and granulosa cell proliferation, respectively [44]. On the other hand, JAK1 appears to be more involved in follicle activation [57]. Therefore, it could be promising for future studies to thoroughly explore potential signaling interactions between KIT and the JAK family members.

Given our observation that KITL supplementation induced p-AKT and p-MAPK3/1, we suspected that KIT might regulate cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation via either or both of these signaling molecules. To test this, E17.5 ovaries were cultured for 5 days with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or the MEK inhibitor U0126, then immunolabeled for histological assessment. In ovaries exposed to LY294002, oocyte growth and follicle development were severely impaired. A similar but less severe outcome was observed in the presence of U0126. These results support previous work showing that PI3K and MAPK3/1 signaling contribute to primordial germ cell and postnatal oocyte growth as well as the initiation of folliculogenesis [36, 37, 41, 42, 45–47]. Interestingly, we found that cyst breakdown was delayed in LY294002-treated ovaries, but normal when MAPK3/1 was inhibited. To our knowledge, these findings are the first to demonstrate that PI3K activity promotes cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. Although we did not find an effect of MAPK3/1 inhibition on cyst breakdown, recent work by Sorrenti et al. found cyst breakdown to be delayed in response to U0126 treatment [47]. This may perhaps suggest that MAPK3/1 plays a dispensable role in cyst breakdown. There is also evidence that other MAPKs are involved [52]. Niu et al. specifically showed that knockdown of MAPK8 or MAPK9 resulted in cyst breakdown being delayed, and that Kit and Kitl were transcriptionally suppressed. However, protein levels of KIT were unaffected, so it is unlikely that MAPK8 and MAPK9 are upstream regulators of KIT-induced cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. Rather, they found a correlation between MAPK knockdown and aberrant E-cadherin junctions between oocytes in cysts [52].

Autophagy and apoptosis are notable physiological features that facilitate cyst breakdown and the modulation of oocyte numbers in the ovary [12, 50], selecting for the subset of oocytes that become encompassed by pregranulosa cells to make up the primordial follicle pool. Given our observation that treatment with LY294002 led to a delay in cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation, we were surprised to find that oocyte numbers were unaffected and comparable to untreated controls. PI3K/AKT signaling is well known for promoting survival by inhibiting pro-apoptotic factors so these results could perhaps be indicative that the mechanisms controlling oocyte survival and apoptosis during cyst breakdown may not necessarily be synergistic or can be regulated by diverse mechanisms. Additionally, it could be possible that PI3K-mediated cell survival is more prevalent in the subset of oocytes that will form follicles as opposed to all oocytes in cysts.

Since we identified that PI3K/AKT signaling promotes cyst breakdown, we wondered whether KIT might be the upstream regulator. We verified that KIT-induced p-AKT occurred specifically through PI3K and not due to crosstalk between other signaling molecules downstream of the receptor. Phosphorylation of AKT was blocked by pretreatment with LY294002 prior to the addition of KITL. To confirm this at the tissue level, we tested whether KITL supplementation would rescue the oocyte growth defect due to PI3K inhibition. Oocytes from ovaries dually dosed with LY294002 and KITL were significantly smaller than control and KITL-treated oocytes and had similar restrictions of oocyte growth as seen in LY294002-treated ovaries. Therefore, we reasoned that if KIT regulated cyst breakdown via a signaling pathway other than PI3K, then KITL supplementation would rescue the effects of LY294002 on cyst breakdown. Indeed, the delay in cyst breakdown due to LY294002 was mitigated in LY294002 + KITL-treated ovaries in comparison to control and KITL-treated ovaries. This suggests that while KIT may primarily signal through PI3K to regulate cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation, other cascades downstream of the receptor could be involved. Oocyte numbers were comparable across conditions, but follicle development was significantly impaired. All follicles appeared to be arrested at the primordial stage in the LY294002 + KITL cohort, while folliculogenesis progressed in control in KITL-treated ovaries. This aligns with genetic studies demonstrating that KIT-mediated PI3K signaling is important for folliculogenesis [45].

The effects of our KITL treatment on oocyte number, cyst breakdown, and follicle development were less pronounced in comparison to our previously reported findings [29], and could partly be explained by the subsequent refinement and optimization of our culture system, the analysis of larger optical sections to give more coverage of the ovary, and having a more robust sample size. In addition, our previous work showed that there were high levels of endogenous KITL expression which could further act to limit the effects of exogenous supplementation. Nonetheless, our results suggest that PI3K likely functions as the primary downstream mediator of KIT-induced cyst breakdown and follicle formation, but that there could also be other signaling pathways involved. If indeed there is heterogeneity in how KIT utilizes these signaling pathways to promote cyst breakdown, then the blocking of a single pathway may not be sufficient to replace KIT activity and could explain why cyst breakdown is not significantly reduced by LY294002 + KITL treatment as opposed to LY294002 alone. Presumably, KIT could circumvent the inhibition of PI3K signaling by working through a different pathway. John et al. have similarly found that while KIT-mediated PI3K signaling promotes the development of ovarian follicles, it is not required to induce their activation [41]. Taken together, these observations further support the idea that PI3K may be the primary of multiple transducers of KIT activity in the developing ovary. Accordingly, PI3K signaling may serve an important but dispensable regulatory role for certain aspects of ovary development controlled by KIT.

Notably, our research strategy primarily employed a pharmacological inhibition approach in order to maintain continuity to the context of our previous studies. Although the ovary culture system also overcomes the challenge of tissue-specific dosing in utero, it is possible that the in vitro approach may not precisely recapitulate the intricacies of signaling interactions and other biochemical processes that are carefully controlled in the in vivo environment. Although the genetic approach would address this issue, it also presents other challenges. Since cyst breakdown takes place over an extended period, it would be difficult to track the process in individual ovaries over time. Furthermore, genetic mutants such as mice carrying the KitY719F point mutation and lacking KIT-induced PI3K activity, are not ideal for studying cyst breakdown since they experience an accelerated depletion of the primordial follicle pool. Additionally, other KIT responses are not compromised in these mice so it is possible that cyst breakdown could still occur normally if another pathway compensates. Similarly, other genetic mutants such as mice with mutations at the Steel or W loci are not amenable to the study of cyst breakdown due to defective migration and proliferation of PGCs and a diminished pool of oocytes at birth. Accordingly, cysts do not appear to form normally. Use of the organ culture system overcomes these issues and permits us to examine signaling mechanisms specifically at the time when cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation are occurring.

Inevitably, some level of crosstalk between signaling pathways is expected, and would lead to convergent mechanisms that regulate cyst breakdown and follicle formation as many of the signaling components activated by KIT are involved in a multiplicity of pathways. Cadherin-facilitated cell adhesion plays a vital role in processes such as tissue morphogenesis and differentiation, and these molecules can also interact with intracellular signaling networks like the PI3K and MAPK pathways [59–61]. E-Cadherin is of particular interest given that its spatiotemporal activity has been implicated in cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. E-Cadherin is highly expressed between oocytes in cysts and its inhibition leads to accelerated cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation while its overexpression impedes these processes [52, 62]. The insulin signaling pathway is also well known to modulate the PI3K and MAPK pathways and would be a promising subject for future study, especially given the observation of an additive effect with KITL in promoting follicle development [63, 64]. Furthermore, the study by Yao et al. showed that insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) can transcriptionally upregulate KITL. Additionally, crosstalk between Notch and PI3K/AKT signaling has been reported in follicle development [65]. It would indeed be interesting to uncover the intricacies of the downstream signaling mechanisms of KIT, NOTCH, cadherins, and the insulin receptor in regulating cyst breakdown, and the extent to which there may be overlap or compensation. In summation, this study contributes the new finding that PI3K signaling promotes establishment of the ovarian reserve, and that PI3K activity is likely the primary mediator of KIT-induced cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. Additional work is required to further elucidate the signaling network around PI3K/AKT activity in cyst breakdown and to characterize downstream mediators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sue Getman for assisting with mouse husbandry and the Gold/Korol lab at Syracuse University for access to their microplate reader.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that no competing or financial interests exist.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health R15 075257.

Contributor Information

Joshua J N Burton, Department of Biology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA.

Amanda J Luke, Department of Biology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA.

Melissa E Pepling, Department of Biology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization was performed by J.B. and M.P. Methodology was done by J.B. Data processing and analysis were performed by J.B. and A.L. J.B. has written the original draft of the manuscript. J.B. and M.P. have written—reviewed and edited the final draft of the manuscript. Funding acquisition was done by M.P.

References

- 1. Chiquoine AD. The identification, origin, and migration of the primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo. Anat Rec 1954; 118:135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ginsburg M, Snow MHL, McLaren A. Primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo during gastrulation. Development 1990; 110:521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lawson KA, Dunn NR, Roelen BAJ, Zeinstra LM, Davis AM, Wright CVE, Korving JPWFM, Hogan BLM. Bmp4 is required for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev 1999; 13:424–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lawson KA, Hage WJ. Clonal analysis of the origin of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Ciba Found Symp 1994; 182:68, discussion 84-91–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ying Y, Liu XM, Marble A, Lawson KA, Zhao GQ. Requirement of Bmp8b for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Mol Endocrinol 2000; 14:1053–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molyneaux KA, Stallock J, Schaible K, Wylie C. Time-lapse analysis of living mouse germ cell migration. Dev Biol 2001; 240:488–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tam PPL, Snow MHL. Proliferation and migration of primordial germ cells during compensatory growth in mouse embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol 1981; 64:133–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pepling ME, Spradling AC. Female mouse germ cells form synchronously dividing cysts. Development 1998; 125:3323–3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lei L, Spradling AC. Mouse primordial germ cells produce cysts that partially fragment prior to meiosis. Development 2013; 140:2075–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pepling ME, Cuevas M, Spradling AC. Germline cysts: a conserved phase of germ cell development? Trends Cell Biol 1999; 9:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pepling ME, Sundman EA, Patterson NL, Gephardt GW, Medico L, Wilson KI. Differences in oocyte development and estradiol sensitivity among mouse strains. Reproduction 2010; 139:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pepling ME, Spradling AC. Mouse ovarian germ cell cysts undergo programmed breakdown to form primordial follicles. Dev Biol 2001; 234:339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rönnstrand L. Signal transduction via the stem cell factor receptor/c-kit. Cell Mol Life Sci 2004; 61:2535–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roskoski R. Structure and regulation of kit protein-tyrosine kinase--the stem cell factor receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 338:1307–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chabot B, Stephenson DA, Chapman VM, Besmer P, Bernstein A. The proto-oncogene c-kit encoding a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus. Nature 1988; 335:88–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Geissler EN, Ryan MA, Housman DE. The dominant-white spotting (W) locus of the mouse encodes the c-kit proto-oncogene. Cell 1988; 55:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Cho BC, Donovan PJ, Jenkins NA, Cosman D, Anderson D, Lyman SD, Williams DE. Mast cell growth factor maps near the steel locus on mouse chromosome 10 and is deleted in a number of steel alleles. Cell 1990; 63:175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams DE, Eisenman J, Baird A, Rauch C, Van Ness K, March CJ, Park LS, Martin U, Mochizuki DY, Boswell HS. Identification of a ligand for the c-kit proto-oncogene. Cell 1990; 63:167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernstein A, Chabot B, Dubreuil P, Reith A, Nocka K, Majumder S, Ray P, Besmer P. The mouse W/c-kit locus. Ciba Found Symp 1990; 148:158, discussion 166-72–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang E, Nocka K, Beier DR, Chu TY, Buck J, Lahm HW, Wellner D, Leder P, Besmer P. The hematopoietic growth factor KL is encoded by the Sl locus and is the ligand of the c-kit receptor, the gene product of the W locus. Cell 1990; 63:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buehr M, McLaren A, Bartley A, Darling S. Proliferation and migration of primordial germ cells in we/we mouse embryos. Dev Dyn 1993; 198:182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geissler EN, McFarland EC, Russell ES. Analysis of pleiotropism at the dominant white-spotting (W) locus of the house mouse: a description of ten new W alleles. Genetics 1981; 97:337–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang EJ, Manova K, Packer AI, Sanchez S, Bachvarova RF, Besmer P. The murine steel panda mutation affects kit ligand expression and growth of early ovarian follicles. Dev Biol 1993; 157:100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dolci S, Williams DE, Ernst MK, Resnick JL, Brannan CI, Lock LF, Lyman SD, Boswell HS, Donovan PJ. Requirement for mast cell growth factor for primordial germ cell survival in culture. Nature 1991; 352:809–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsui Y, Toksoz D, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S, Williams D, Zsebo K, Hogan BLM. Effect of steel factor and leukaemia inhibitory factor on murine primordial germ cells in culture. Nature 1991; 353:750–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pesce M, Farrace MG, Piacentini M, Dolci S, De Felici M. Stem cell factor and leukemia inhibitory factor promote primordial germ cell survival by suppressing programmed cell death (apoptosis). Development 1993; 118:1089–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Runyan C, Schaible K, Molyneaux K, Wang Z, Levin L, Wylie C. Steel factor controls midline cell death of primordial germ cells and is essential for their normal proliferation and migration. Development 2006; 133:4861–4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoshida H, Takakura N, Kataoka H, Kunisada T, Okamura H, Nishikawa SI. Stepwise requirement of c-kit tyrosine kinase in mouse ovarian follicle development. Dev Biol 1997; 184:122–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones RL, Pepling ME. KIT signaling regulates primordial follicle formation in the neonatal mouse ovary. Dev Biol 2013; 382:186–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang J, Roy SK. Growth differentiation Factor-9 and stem cell factor promote primordial follicle formation in the hamster: modulation by follicle-stimulating Hormone1. Biol Reprod 2004; 70:577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Asadi-Azarbaijani B, Santos RR, Jahnukainen K, Braber S, Duursen MBM, Toppari J, Saugstad OD, Nurmio M, Oskam IC. Developmental effects of imatinib mesylate on follicle assembly and early activation of primordial follicle pool in postnatal rat ovary. Reprod Biol 2017; 17:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reynaud K, Cortvrindt R, Smitz J, Driancourt M-A. Effects of kit ligand and anti-kit antibody on growth of cultured mouse preantral follicles. Mol Reprod Dev 2000; 56:483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reynaud K, Cortvrindt R, Smitz J, Bernex F, Panthier JJ, Driancourt MA. Alterations in ovarian function of mice with reduced amounts of KIT receptor. Reproduction 2001; 121:229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parrott JA, Skinner MK. Kit-ligand/stem cell factor induces primordial follicle development and initiates folliculogenesis. Endocrinology 1999; 140:4262–4271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 2000; 103:211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Miguel MP, Cheng L, Holland EC, Federspiel MJ, Donovan PJ. Dissection of the c-kit signaling pathway in mouse primordial germ cells by retroviral-mediated gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002; 99:10458–10463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. John GB, Gallardo TD, Shirley LJ, Castrillon DH. Foxo3 is a PI3K-dependent molecular switch controlling the initiation of oocyte growth. Dev Biol 2008; 321:197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reddy P, Shen L, Ren C, Boman K, Lundin E, Ottander U, Lindgren P, Liu Y, Sun Q, Liu K. Activation of Akt (PKB) and suppression of FKHRL1 in mouse and rat oocytes by stem cell factor during follicular activation and development. Dev Biol 2005; 281:160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ezzati MM, Baker MD, Saatcioglu HD, Aloisio GM, Pena CG, Nakada Y, Cuevas I, Carr BR, Castrillon DH. Regulation of FOXO3 subcellular localization by kit ligand in the neonatal mouse ovary. J Assist Reprod Genet 2015; 32:1741–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kissel H. Point mutation in kit receptor tyrosine kinase reveals essential roles for kit signaling in spermatogenesis and oogenesis without affecting other kit responses. EMBO J 2000; 19:1312–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. John GB, Shidler MJ, Besmer P, Castrillon DH. Kit signaling via PI3K promotes ovarian follicle maturation but is dispensable for primordial follicle activation. Dev Biol 2009; 331:292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Zheng N, Xu X, Yang J, Xia G, Zhang M. MAPK3/1 participates in the activation of primordial follicles through mTORC1-KITL signaling. J Cell Physiol 2018; 233:226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhao L, Du X, Huang K, Zhang T, Teng Z, Niu W, Wang C, Xia G. Rac1 modulates the formation of primordial follicles by facilitating STAT3-directed Jagged1, GDF9 and BMP15 transcription in mice. Sci Rep 2016; 6:23972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang K, Wang Y, Zhang T, He M, Sun G, Wen J, Yan H, Cai H, Yong C, Xia G, Wang C. JAK signaling regulates germline cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation in mice. Biol Open 2018; 7:bio029470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saatcioglu HD, Cuevas I, Castrillon DH. Control of oocyte reawakening by kit. PLOS Genet 2016; 12:e1006215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Packer AI, Hsu YC, Besmer P, Bachvarova RF. The ligand of the c-kit receptor promotes oocyte growth. Dev Biol 1994; 161:194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sorrenti M, Klinger FG, Iona S, Rossi V, Marcozzi S, Felici MDE. Expression and possible roles of extracellular signal-related kinases 1-2 (ERK1-2) in mouse primordial germ cell development. J Reprod Dev 2020; 66:399–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang J, Liu W, Sun X, Kong F, Zhu Y, Lei Y, Su Y, Su Y, Li J. Inhibition of mTOR signaling pathway delays follicle formation in mice. J Cell Physiol 2017; 232:585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang C, Zhou B, Xia G. Mechanisms controlling germline cyst breakdown and primordial follicle formation. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017; 74:2547–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhihan T, Xinyi M, Qingying L, Rufei G, Yan Z, Xuemei C, Yanqing G, Yingxiong W, Junlin H. Autophagy participates in cyst breakdown and primordial folliculogenesis by reducing reactive oxygen species levels in perinatal mouse ovaries. J Cell Physiol 2019; 234:6125–6135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang Y-Y, Sun Y-C, Sun X-F, Cheng S-F, Li B, Zhang X-F, De Felici M, Shen W. Starvation at birth impairs germ cell cyst breakdown and increases autophagy and apoptosis in mouse oocytes. Cell Death Dis 2017; 8:e2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Niu W, Wang Y, Wang Z, Xin Q, Wang Y, Feng L, Zhao L, Wen J, Zhang H, Wang C, Xia G. JNK signaling regulates E-cadherin junctions in germline cysts and determines primordial follicle formation in mice. Development 2016; 143:1778–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu K, Rajareddy S, Liu L, Jagarlamudi K, Boman K, Selstam G, Reddy P. Control of mammalian oocyte growth and early follicular development by the oocyte PI3 kinase pathway: new roles for an old timer. Dev Biol 2006; 299:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim S-Y, Kurita T. New insights into the role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity in the physiology of immature oocytes: lessons from recent mouse model studies. Eur Med Journal Reprod Heal 2018; 3:119–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Du X-Y, Huang J, Xu L-Q, Tang D-F, Wu L, Zhang L-X, Pan X-L, Chen W-Y, Zheng L-P, Zheng Y-H. The proto-oncogene c-src is involved in primordial follicle activation through the PI3K, PKC and MAPK signaling pathways. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012; 10:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56. Li-Ping Z, Da-Lei Z, Jian H, Liang-Quan X, Ai-Xia X, Xiao-Yu D, Dan-Feng T, Yue-Hui Z. Proto-oncogene c-erbB2 initiates rat primordial follicle growth via PKC and MAPK pathways. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2010; 8:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sutherland JM, Frost ER, Ford EA, Peters AE, Reed NL, Seldon AN, Mihalas BP, Russel DL, Dunning KR, McLaughlin EA. Janus kinase JAK1 maintains the ovarian reserve of primordial follicles in the mouse ovary. Mol Hum Reprod 2018; 24:533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Takeda K, Noguchi K, Shi W, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat3 gene leads to early embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94:3801–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell 1996; 84:345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reddy P, Liu L, Ren C, Lindgren P, Boman K, Shen Y, Lundin E, Ottander U, Rytinki M, Liu K. Formation of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion activates AKT and mitogen activated protein kinase via phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase and ligand-independent activation of epidermal growth factor receptor in ovarian cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 2005; 19:2564–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yan H, Wen J, Zhang T, Zheng W, He M, Huang K, Guo Q, Chen Q, Yang Y, Deng G, Xu J, Wei Zet al. Oocyte-derived E-cadherin acts as a multiple functional factor maintaining the primordial follicle pool in mice. Cell Death Dis 2019; 10:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang C, Roy SK. Expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin in perinatal hamster ovary: possible involvement in primordial follicle formation and regulation by follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology 2010; 151:2319–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kezele PR, Nilsson EE, Skinner MK. Insulin but not insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes the primordial to primary follicle transition. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2002; 192:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yao K, Lau S-W, Ge W. Differential regulation of kit ligand A expression in the ovary by IGF-I via different pathways. Mol Endocrinol 2014; 28:138–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang L-Q, Liu J-C, Chen C-L, Cheng S-F, Sun X-F, Zhao Y, Yin S, Hou Z-M, Pan B, Ding C, Shen W, Zhang X-F. Regulation of primordial follicle recruitment by cross-talk between the Notch and phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)/AKT pathways. Reprod Fertil Dev 2016; 28:700–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.