Abstract

Human fetal membrane and maternal decidua parietalis form one of the major feto-maternal interfaces during pregnancy. Studies on this feto-maternal interface is limited as several investigators have limited access to the placenta, and experience difficulties to isolate and maintain primary cells. Many cell lines that are currently available do not have the characteristics or properties of their primary cells of origin. Therefore, we created, characterized the immortalized cells from primary isolates from fetal membrane-derived amnion epithelial cells, amnion and chorion mesenchymal cells, chorion trophoblast cells and maternal decidua parietalis cells. Primary cells were isolated from a healthy full-term, not in labor placenta. Primary cells were immortalized using either a HPV16E6E7 retroviral or a SV40T lentiviral system. The immortalized cells were characterized for the morphology, cell type-specific markers, and cell signalling pathway activation. Genomic stability of these cells was tested using RNA seq, karyotyping, and short tandem repeats DNA analysis. Immortalized cells show their characteristic morphology, and express respective epithelial, mesenchymal and decidual markers similar to that of primary cells. Gene expression of immortalized and primary cells were highly correlated (R = 0.798 to R = 0.974). Short tandem repeats DNA analysis showed in the late passage number (>P30) of cell lines matched 84-100% to the early passage number (<P10) of the cell lines revealing there were no genetic drift over the passages. Karyotyping also revealed no chromosomal anomalies. Creation of these cell lines can standardize experimental approaches, eliminate subject to subject variabilities, and benefit the reproductive biological studies on pregnancies by using these cells.

Keywords: Human placental fetal membrane, fetal-maternal cells, HPV16E6E7, SV40T-based immortalization

Human placental fetal membrane derived fetal-in-origin amnion epithelial cells, amnion mesenchymal cells, chorion mesenchymal cells, chorion trophoblast cells and maternal-in-origin decidual parietalis cells were immortalized for the reproductive biology studies.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Human amniochorion (fetal membranes) and decidua parietalis form one of the major feto-maternal interfaces during pregnancy [1, 2]. This interface is composed of amnion epithelial cells that line the innermost layer of the intrauterine cavity near the foetus, an extracellular matrix region enriched in various types of collagens, both amnion and chorion mesenchymal cells and chorion trophoblast cells that are connected to maternal decidua [1, 3, 4]. Amniochorion is fetal in origin and is a major source of various biochemicals, including various endocrine factors, and protects the foetus during pregnancy [1]. Amniochorion is avascular; however, it receives nutrients and other essential supplies for its own growth and delivery to the foetus likely via amniotic fluid from maternal decidua. Decidua borders along with the chorion trophoblast layer form the feto-maternal barrier. The structural and mechanical integrity of this interface is essential for the maintenance of pregnancy. Like the placental and decidua basalis interface, immune tolerance is also critical at the fetal membrane-decidual junction, as resident decidual immune cells are prevented from invading the membrane region unless there is compromise at the chorio-decidual interface [5, 6]. Although this mechanism is not fully understood, our lab has recently identified constitutive expression of human leukocyte antigen G (HLA-G) in the chorion trophoblast layer, which is also a major producer of progesterone that can act as an anti-inflammatory agent. Invasion of immune cells from the decidual layer to the amniochorion (chorioamnionitis) is often associated with pregnancy pathologies [5, 7–9]. Physiologic and pathologic senescence has been reported in both the amniochorion and decidua, where ageing of these tissues leads to inflammation [10–12]. This proinflammatory surge is also associated with parturition at both term and preterm [13]. Thus, amniochorion-decidual interface plays a major role in maintaining pregnancy and promoting parturition.

Studies using interface cells from the amniochorion-decidual regions are limited, and ambiguity exists in delineating the functions of various cell types in mechanical, immune, and endocrine functions during pregnancy and parturition [5, 14–23]. One of the major challenges is isolation of primary cells and their maintenance for in vitro studies. For example, WISH cells are traditionally used to study the functional role of amnion epithelial cells [24]. However, the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) properties of amnion epithelial cells in culture have turned this cell population into a mesenchymal phenotype and do not necessarily reflect epithelial characteristics [25–28]. Thus, data are often confounded due to mixed culture of parent cells and transitioning cells and becomes difficult to reproduce in different lab settings. Similarly, chorion trophoblast cells also exhibit transition properties to become mesenchymal cells and lose their trophoblastic characteristics. Placental trophoblast cells are used in place of chorion trophoblast cells. Although they may arise from the same lineage, placental and chorion trophoblast cells demonstrate spatial, temporal, and functional differences [29].

We and others have earlier reported cell culture protocols for cells from the membranes and decidua [29–37]. The last cell type to be added to this repertoire is chorion trophoblast cells, whose culture is notoriously contaminated with the overgrowth of decidual stromal cells of chorion mesenchymal cells from the matrix [29]. Recently, we have reported a protocol to isolate chorion trophoblast cells, with the purity of such cultures being around 92% [29]. As mentioned above, there are still several limitations in using primary cells. Since cultured cells cannot proliferate indefinitely and the impracticality of conducting multiple experiments from the same placental cell primary isolates, we have immortalized cells using primary isolates from the amniochorionic membrane (amnion epithelial cells, extracellular matrix amnion and chorion mesenchymal cells, and chorion trophoblast cells) and decidua parietalis cells. Cellular immortalization primarily involves loss of negative regulators of cell cycle progression, and each primary cell requires a unique approach to convert them into a cell line for efficient and infinite cell growth [38–42]. In this report, we report the generation of various cell lines for studies on the fetal membrane-decidual interface. We present the following: (1) approaches to convert primary cells to cell lines; (2) cell culture conditions of immortalized cells; (3) cellular characterization (morphology and markers); (4) gene expression profiles; (5) key significant signalling responses; and (6) genomic stability of cells. Cell line data are compared and validated to their respective primary celldata.

Methods

Institutional review board approval

Placental specimens used for this study were deidentified and considered as discarded human specimens that do not require institutional review board (IRB) approval. Placental specimens were collected from John Sealy Hospital at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, USA, in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of approved protocols for various studies (UTMB 11-251; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston).

Primary human amnion epithelial cell isolation

All primary cells were isolated from the placental fetal membranes of patients who had completed a full-term pregnancy and underwent elective caesarean delivery before the onset of labour (gestational age ≥ 38 weeks). Primary amnion epithelial cells (pAECs) were extracted as described previously [43]. Briefly, the amniotic membranes were mechanically separated from the chorion layer and were washed with prewarmed saline (0.9% sodium chloride, Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) to remove excess blood and cellular debris. Immediately after washing, tissues were transferred to prewarmed sterile Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS; Corning®, Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin (P/S; Corning, Cat. #30-001-CI) and 1% amphotericin B (AMB; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. #A2942, St. Louis, MO, USA) and cut into 1 cm x 1 cm pieces in the hood. The tissue was then transferred to 50 mL conical tubes and incubated in the prewarmed digest buffer (0.125% collagenase A [Sigma] and 0.25% trypsin [Sigma-Aldrich] in HBSS) for 35 min at 37°C. The tissue was gently vortexed intermittently. After incubation, an equal volume of pAECs complete media (DMEM/F12; Gibco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum [FBS, Sigma, Cat. # F2442], 1% P/S [Sigma-Aldrich], 1% AMB [Sigma-Aldrich], and 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor [EGF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA]) was added to the tissue to neutralize the enzymatic digestion and filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer. The undigested remaining tissues were collected in new 50 mL conical tubes and incubated with the digest buffer for the second digestion for 20 min at 37°C. After neutralization, the cells were filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer into previously collected cells to pool them together. Then, collected cells were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and were resuspended and grown in a T75 flask with the complete media. All experiments with pAECs were done with passage 1 (P1) unless explained otherwise.

Primary human amnion mesenchymal cell isolation and culture

Primary amnion mesenchymal cells (pAMCs) were isolated as described previously [27]. Briefly, amnion membrane tissue was collected in the same manner as the isolation of pAECs and cut into 5 cm x 5 cm pieces. After washing tissue pieces three times with HBSS (Corning®), the tissue was transferred into 50 mL conical tubes. A total of 25 ml of digest buffer-I (0.25% trypsin/EDTA, Corning®, Cat. #25-053-CI in HBSS) were added into 50 mL tissue-containing tubes and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. During incubation, the tissue was vortexed well every 15 min. Then, the tissue was washed three times with ice cold HBSS to remove trypsinized, loosened AECs. The tissues were then transferred to new 50 mL conical tubes containing 25 mL of digest buffer-II (1 mg/mL collagenase [Sigma, Cat. #C0130-1G] and 25 μg/mL DNase-I [Sigma, Cat. #DN25-100MG] in serum-free [SF] DMEM) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Then, collagenase was neutralized with an equal volume of complete DMEM media (DMEM/F12, 5% FBS, 1% P/S, and 1% AMB), and the cells were filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer. Collected cells were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at RT and were resuspended and grown in a complete DMEM media. All experiments with pAMCs were done withP1.

Primary human chorion trophoblast cell and chorion mesenchymal cell isolation

Primary chorion trophoblast cells (pCTCs) and primary chorion mesenchymal cells (pCMCs) were isolated as described previously [29]. Briefly, the chorion layer was mechanically separated from the amnion layers, and the decidua layer was gently removed with a scalpel. The tissue was then washed well with prewarmed saline to remove excess cell debris and blood. Then, the tissue was cut into 2 cm x 2 cm pieces and collected in 50 mL conical tubes. Tissue pieces were treated with dispase (2.4 U/mL in HBSS, Sigma) two times for 8 min per incubation and between the treatment they were allowed to rest in the complete media for 8 min. The tissues were rinsed with 10% FBS containing DMEM (supplemented with 1% P/S and 1% AMB) and transferred to new 50 mL conical tubes. Digest buffer-I [0.75 mg/mL collagenase [Sigma] and 25 μg/mL DNase-I [Sigma] in HBSS) was added to the tissue and incubated for 3 hr at 37°C. Loosened cells were CMCs. CMCs were filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, resuspended and grown in complete DMEM media. The remaining undigested tissues were collected in new 50 mL conical tubes, treated with digest buffer-II (0.25% trypsin and 25 μg/mL DNase-I (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], Corning™) for 5 min at 37°C. Immediately after, the tissue was vortexed, filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, resuspended and grown in complete CTC media (DMEM/F12, 0.2% FBS, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol [Gibco, Cat. #50-114-7851], 0.5% P/S, 0.3% BSA [Gemini Bio, Cat. #700-100P, West Sacramento, CA, USA], 1% ITS-X-supplement [Gibco, Cat. #51-500-056], 2 μM CHIR99021 [Sigma, Cat. #SMl1046], 0.5 μM A83-01 [Sigma, Cat. #SML0788], 1 μM SB431542 [Sigma, Cat. #616464], 1.5 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid [Sigma, Cat. #A4544], 50 ng/mL EGF [Sigma, Cat. #E4127], 0.8 mM VPA [Sigma, Cat. #P6273] and 5 μM Y27632 [Millipore Sigma, Cat. #68-800-05MG]). All experiments with pCMCs and pCTCs were done withP1.

Primary human decidual cell isolation

Primary decidual cells (pDECs) were isolated as previously described [44]. Briefly, the chorion layer was mechanically removed, gently rinsed in prewarmed saline, and cut into 5 cm x 5 cm squares. The decidual layer was dissected from the chorion using a scalpel. The tissue was then minced into small pieces, digested in digest buffer-I (0.125% trypsin [Gibco, Cat# 15050-065] and 0.02% DNase-I [Sigma, Cat# D4527] in HBSS] for 30 min at 37°C with intermittent vortexing. Then, the pellet was collected after centrifuging at 3000 rpm for 10 min at RT and resuspended in digest buffer-II (0.125% trypsin, 0.02% DNase-I, and 0.2% collagenase type IA [Sigma, Cat#C2674] in HBSS) for 60 min at 37°C. The digestion was neutralized by adding an equal volume of complete DMEM media and filtering the cells through four layers of sterile gauze. The collected cells were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at RT, and the pellet was resuspended in 4 mL of the same media that is used in preparing gradient dilutions. The OptiPrep™ Discontinuous Gradient (OptiPrep™) was prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, using 40% Optiprep, a working solution (WS) was prepared in the SF media by mixing two volumes of OptiPrep with one volume of SF media. Starting with the 40% solution, 4 mL of each solution were layered into a 50 mL conical tube using a 5 cc syringe fitted with a bore needle (18G) for acquisition, ranging from 4% to 40%. After preparing the gradients, decidual cells were added (1.027-1.038 g/mL, 4-6%) to the top of the gradient, then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 35 min at RT. The cells were collected, washed with SF media (4x volume to collected cells from the column) and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at RT. The pellet was resuspended with complete DMEM/F12 and placed in T25 flasks.

Immortalization of the cells

Human papillomavirus type 16 E6E7 (HPV16 E6E7) immortalization

pAECs, pAMCs, pCMCs and pDECs were immortalized with the HPV16 E6E7 retrovirus [41, 45, 46]. Retroviruses were obtained from the PA317 LXSN 16E6E7 (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA, Cat. No: ATCC® CRL-2203™) cell line, which carries the pLXSN16E6E7 vector containing human papilloma virus (HPV) type 16 E6 and E7 genes under the control of the Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMuLV) promoter-enhanced sequences [41]. Healthy, ~50% confluent primary cells were seeded in 6-well plates at the following numbers: P1 AEC (from placenta #877), 250,000; P1 AMC (from placenta #864), 70,000; P1 CMC (from placenta #870), 100,000; and P2 DEC (from placenta #864), 100,000. The next day, the cells were infected with 500 μL of a transduction mixture containing 50 μL of retroviral supernatant (ATCC® CRL-2203™) and 5 μL of 1 μg/μL protamine sulphate (Fresenius Kabi, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) in SF culture media, which was incubated at 37°C for 6 h. The complete media was then added to the wells, and the cells were incubated for additional 18 h. This media was replaced with the complete media 24 h after the initial retroviral infection. Antibiotic selection was started at 48 h after the infection with 50 μg/mL of G418 (Corning®, REF: 30-234-CR, Lot No: 30234423) for 5 days. The selected cells were then expanded until P3-4, and the frozen stocks were stored in liquid nitrogen for later usage.

SV40T immortalization

pCTCs were immortalized with the SV40T lentivirus [47–50]. Large T antigen producing lentivirus was purchased (ALSTEM, Inc., Cat. #CILV01, Richmond, CA). P1 pCTCs (from placenta #981) were plated at 300,000 in 6-well plates and incubated at 37°C for overnight. The next day, the cells were infected with 1 mL of a transduction mixture containing 10 μL of retroviral supernatant and 4 μL of TransPlus reagent (ALSTEM, Cat#V050) in complete media. The media was replaced with fresh complete media 24 h later. The antibiotic selection was started at 72 h after the initial infection with 1 μg/mL of puromycin (Sigma, Cat. No: P8833-25MG, Lot No: 109M4022V) for 7 days. The selected cells were expanded and stored as described above.

The maintenance of the immortalized cells

Immortalized amnion epithelial cells (AEC) culture

Immortalized AECs, named as hFM-AEC (Supplementary Table S1), were cultured in complete keratinocyte serum free media (KSFM – Gibco #17005042) supplemented with human recombinant epidermal growth factor (rEGF, #10450-013, 2.5 μg), bovine pituitary extract (BPE, #13028-014, 25 mg) and primocin (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat #cat-pm-1, 50 mg/mL, Carlsbad, CA, US) in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. For regular maintenance, 90% confluent cells were trypsinized for 10 min in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator, and trypsin (0.25% trypsin, 2.21 mM EDTA, Corning®) was inactivated using DMEM containing 10% FBS, centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm at RT. The pellet was resuspended in complete KSFM media, and the cells were split at a 1:5 ratio up to P40. The media was changed every 2 days.

Immortalized amnion mesenchymal cells (AMC), chorion mesenchymal cells (CMC) and decidua (DEC) cultures

Immortalized AMC, CMC and DEC, named as hFM-AMC, hFM-CMC and hFM-DEC (Supplementary Table S1), were cultured in complete DMEM media in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. For regular maintenance, 90% confluent cells were trypsinized for 4 min in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator, and trypsin (Corning®) was inactivated using DMEM containing 10% FBS, centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm at RT. The pellet was resuspended in complete DMEM media, and the cells were split at a 1:5 ratio up to P40. The media was changed every 3 days.

Immortalized chorion trophoblast cells (CTC) culture

Immortalized CTC, named as hFM-CTC (Supplementary Table S1), were cultured in complete CTC media in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. For regular maintenance, 90% confluent cells were trypsinized for 10 min in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator, and trypsin (Corning®) was inactivated using DMEM containing 10% FBS, centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm at RT. The pellet was resuspended in complete CTC media, and the cells were split at a 1:5 ratio up to P40. The media was changed every 2 days.

Morphological analysis

The morphological analysis of the cells was analysed based on the phase contrast images. The cells were seeded around 70-75% confluency before imaging for the phase contrast images using a Keyence microscope (Keyence Corp., Osaka, Japan).

Marker protein expression analysis with immunocytochemistry

A quantity (30,000) of amnion epithelial cells (pAEC and hFM-AEC) and chorion trophoblast cells (pCTC and hFM-CTC) were seeded into 8-well chamber slides (CELLTREAT Scientific Products, Pepperell, MA, USA, Cat. No: 229167). A quantity (20,000) of mesenchymal cells (pAMC and hFM-AMC; pCMC and hFM-CMC), and decidual cells (pDEC and hFM-DEC) were seeded into 8-well chamber slides (CELLTREAT Scientific Products) as well. After fixing, the cells were blocked with 3% BSA/TBST for 30 min at RT, and then incubated with primary antibodies for cytokeratin-18 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cat. No: ab668, DF: 1:500), cytokeratin-7 (Abcam, Cat. No: ab9021, DF: 1:500), vimentin (Abcam, Cat. No: ab92547, DF: 1:300) and prolactin (R&D Systems, Cat. No: AF682) diluted at 3% BSA/TBST overnight at 4°C. The next day, the cells were washed three times for 10 min with 1 x TBST and incubated with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor® 488, Abcam, Cat. No: ab150073, Lot: GR269274-4 and Alexa Fluor® 594, Invitrogen, Cat. No: ab150080, Lot: GR3323881-1, respectively) diluted in BSA/TBST for 1 h at RT. Then, the cells were stained with DAPI (Invitrogen), washed three times for 10 min, and the FMi-OOC devices filled with cold 1xPBS.

Western blot (WB) analysis

Immunoblotting was done as previously described with some modifications [51]. Total proteins (20 μg) were loaded into 4–15% gradient polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and subjected to electrophoresis. Subsequently, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories) by semi-dry electrophoretic transfer (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and the membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk/TBST (Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween20) for 2 h at RT. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies of p53 (Abcam, Cat. No: ab1101, Lot No: GR3218081-19, DF: 1:500), p-p38 MAPK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA, Cat. No: 4511S, Lot No: 10, DF: 1:300), p38 MAPK (Cell Signaling, Cat. No: 9212S, Lot No: 26, DF: 1:1000), and β-actin (Sigma, Cat. No: A5441-2 ml, Lot No: 079M4799V, DF: 1:15,000) diluted in 5% non-fat dry milk/TBST overnight at 4°C, with secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA, Cat. No: 1030-05, Lot: K3515-T566, DF: 1:15,000) for 1 h at RT. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescent Western blotting solution (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with ChemiDoc™ Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For immunoblot quantitative analysis, Image Lab™ software was used (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Ribonucleic acid sequence (RNA seq) analysis

For total RNA isolation, cells were counted after resuspending the pellet and approximately 1.5 million cells were plated per 100 mm dish containing complete media at 37°C, 5% CO2. When cells reached 70-80% confluence, total RNA was extracted using the PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies, Cat. #12183020) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cells were lysed using lysis buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and homogenized. The wash step was performed using 75% ethanol, and the samples were transferred to spin columns. After centrifuging at 10,000 rpm for 15 s, the columns were treated with 5 U of DNase-I and incubated for 15 min at RT. Impurities were removed by subsequent washing, and the purified total RNA was eluted in RNase-free water. RNA quality and yield were accessed by the A260/A280 ratio using spectrophotometry (BioTek Synergy H4 Hybrid Reader).

A total of 10 samples were analysed by RNA seq. Total RNA (5 μg) was used for the reverse transcriptase reaction. The cDNA was applied into an Illumina next generation sequencer (NextSeq 550). Randomly primed Click Seq (CS) for RNA seq libraries were prepared as described previously [52]. The raw reads were trimmed and quality filtered as described [52]. For random-primed Click Seq, short reads were mapped to hg38 genomes using STAR aligner. Gene expression was counted with the feature Counts program, and the output was read into a matrix in R. Sample counts for each gene were then normalized, and Wald tests were performed to determine differential expression.

Cytogenetic analysis

Giemsa banded (G-banded) karyotyping analysis was performed for the chromosome analysis of immortalized cells. Cell samples were prepared when cells were in log phase, undergoing active division. The day before the collection, the cells were seeded at ~40% of confluency in T75 flasks. AEC: 1,400,000/T75; AMC and CMC: 850,000; CTC: 1,200,000; and DEC: 700,000 cells were seeded to T75 flasks overnight. The next day, the cells were treated with 10 μL of KaryoMAX™ Colcemid™ (Gibco™, Cat. No: 15210040, 10 ug/mL)/10 mL complete media for 1 h in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. Then, all cells (including floating cells) were collected and centrifuged at 500 rpm for 7 min at RT. The supernatants were carefully removed, and the pellets were resuspended in 8 mL 0.075 M KCL hypotonic solution for 7 min at RT, then centrifuged again at 500 rpm for 7 min at RT. The supernatants were carefully removed, and the pellets were slowly resuspended in fixation solution (3:1, methanol: acetic acid) for 15 min at RT. The fixative washing step was repeated two times. Then, the cells were stored in a fixative at 4°C until being shipping to Creative Bioarray LLC., Shirley, NY, USA, where G-banded karyotyping services were conducted. In some cases, live cells were shipped at 40% confluency in the Petaka G3™ Cell Culture Cassette (Gemini Bio, West Sacramento, CA, Cat. No: LTPTK25) at RT. Cytogenetic analysis was performed on 20 G-banded metaphase spreads for each cellline.

Short tandem repeats (STR) deoxyribonucleic acid profiling analysis

The 80-85% confluent cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 125 rpm for 10 min at RT. Then, the supernatants were discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in 1 x PBS. Cells were quantified and adjusted to the required cell numbers. Then, 40 μL of 1 x 106 cells/mL were seeded in the centre of the circle of a sample collection card (ATCC, Cat. No: 135-XV™), and the cells were air-dried for 15 min at RT in the hood. Then, the cells in the sample collection card were placed in a desiccant pack and shipped to the ATCC. Seventeen STR loci plus the gender determining locus amelogenin were amplified using the commercially available PowerPlex® 18D Kit from Promega. The cell line sample was processed using the ABI Prism® 3500xl Genetic Analyzer. Data were analysed using GeneMapper® ID-X v1.2 software (Applied Biosystems). Appropriate positive and negative controls were run and confirmed for each sample submitted. All STR analysis experiments were performed and analysed at the ATCC (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). STR analysis matching was performed using a Tanabe algorithm, where the matching criterion is based on an algorithm that compares the number of shared alleles between two cell line samples, expressed as a percentage [8]. Cell lines with ≥80% match are considered to be related and/or derived from common ancestry.

Statistical analysis

RNA seq analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc. San Diego, CA, USA) for Pearson’s correlation with 95% confidence interval. The PCA was done using the R-package DeSeq2 as part of the standard vignette used during the differential gene expression analysis. The values for the PCA were the variance in gene expression.

Results

Primary cells immortalizations were achieved by inhibiting p53 expression and function

The immortalization of the AECs, AMCs, CMCs, and DECs were performed by infecting the primary cells with HPV type 16-derived E6E7 proteins expressing retroviruses (HPV16E6E7). The immortalization of the CTCs was achieved by introducing simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen-expression lentiviruses (SV40T) (Supplementary Table S1). The successfully infected cells were further selected by antibiotics (G418 for HPV16E6E7 and puromycin for SV40T) to establish the immortalized cell lines.

First, we checked the expression of p53 in the immortalized cells, since it has been reported that HPV16E6E7 reduces the expression by degrading p53 protein whereas SV40T binds to the p53 protein, making it inactive [41, 53, 45, 54–56]. Fig. 1 shows the inhibition of the p53 expression in the immortalized AECs (P8), AMCs (P7), CMCs (P7), and DECs (P12) compared to their respective primary cells. However, immortalized CTCs (P6) showed an increased p53 expression as has been reported in the SV40T-based immortalized cells. p53 is reported to be bonded to large T antigens from SV40T, and this bond stabilizes it, rendering it non-functional in specific cells. Therefore, although expressed, p53 loses its functional ability to create a check point during the cell cycle.

Figure 1.

Primary cells were immortalized by stable transfection of HPV16E6E7 and SV40T genes. Western blot analysis was conducted with 20 μg of total proteins to detect total p53 protein expressions in the primary and immortalized cells. HPV16E6E7-based cell immortalization was achieved by the inhibition of p53 protein expression. However, SV40T-based cell immortalization was achieved by the inhibition of p53 protein function. β-actin was detected as a loading control (N = 3). AEC-amnion epithelial cells, AMC-amnion mesenchymal cells, CMC-chorion mesenchymal cells, CTC-chorion trophoblast cells and DEC-decidua cells.

Primary and their respective immortalized cells are morphologically identical

Next, we analysed the morphology of each immortalized cell by comparing it with the primary origin of the cells. AECs (P7), both primary and immortalized, show cobblestone-like epithelial morphology (Fig. 2A). AMCs (P6) and CMCs (P6) show classic fibroblast-like mesenchymal morphology in both primary and immortalized cells (Fig. 2B,C). Primary and immortalized CTCs (P5) show epithelial-like rounder morphology and grow in clusters (Fig. 2D). Maternal DECs (P8), both primary and immortalized, also show fibroblast-like mesenchymal morphology (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Cell morphology of the primary and immortalized cells. Immortalized cells reserved the morphology of the parent primary cells. Phase-contrast images of the AEC (A), AMC (B), CMC (C), CTC (D), and DEC (E) (N = 3). Scale bar, 20 μm. AEC, amnion epithelial cells. AMC, amnion mesenchymal cells. CMC, chorion mesenchymal cells. CTC, chorion trophoblast cells. DEC, decidua cells. p, primary. hFM, human fetal membrane.

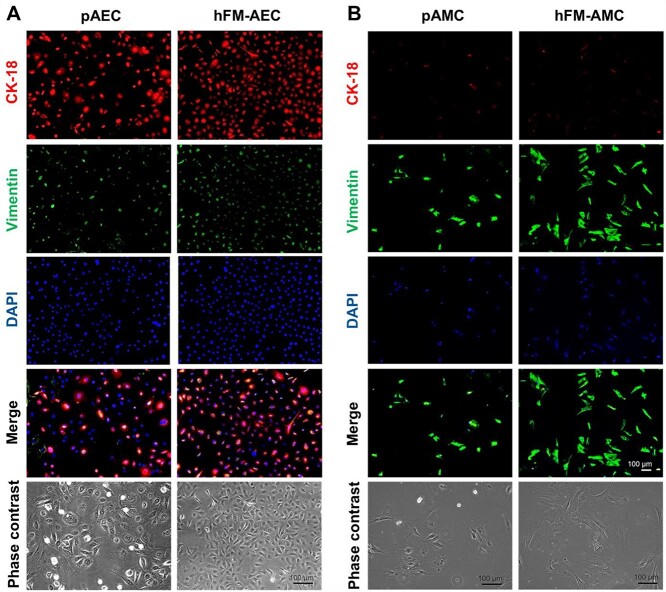

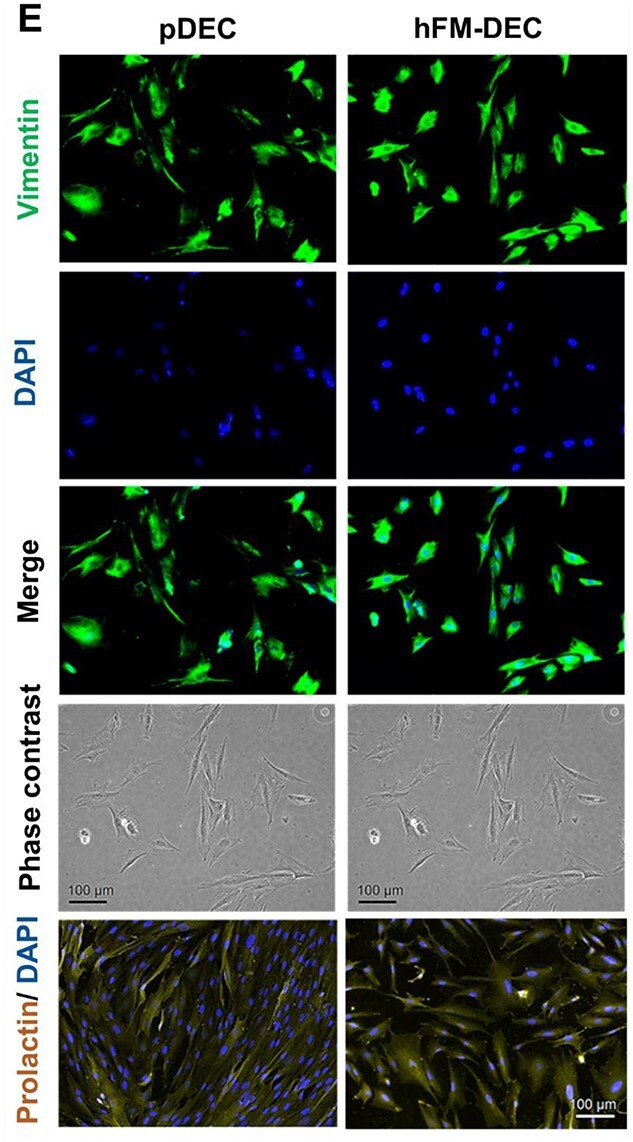

Primary and their respective immortalized cells exhibit same cell type-specific markers

To further characterize immortalized cells for their cell-type specificity, we next checked the main cell type-specific marker protein expression patterns by comparing them with their respective primary cells of origin (Fig. 3A-E). As shown in Fig. 3A, both primary and immortalized AECs (P10) expressed the epithelial-specific marker cytokeratin-18 predominantly and the mesenchymal-cell marker vimentin modestly (Fig. 3A). Both the primary and immortalized AMCs (P12) and CMCs (P12) showed expression of the mesenchymal cell marker vimentin (Fig. 3B,C). As expected, epithelial cell marker cytokeratin proteins were barely expressed in those mesenchymal cells (Fig. 3B,C). Both the primary and immortalized CTCs (P9) showed the expression of the epithelial cell-specific marker cytokeratin-7 abundantly and the mesenchymal cell-specific vimentin minimum (Fig. 3D). Both primary and immortalized maternal DECs (P17) showed the expression of prolactin and the mesenchymal marker vimentin in a similar manner (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Cell type-specific marker protein expression in the wild type and immortalized cells. Immunocytochemical staining analysis showing immortalized cells expressing cell type-specific marker proteins. A) Both the primary AEC and hFM-AEC express the epithelial cell-specific marker protein CK-18 predominantly and the mesenchymal cell marker vimentin modestly (N = 3). Both the primary and immortalized mesenchymal cells (AMC and CMC) express the mesenchymal cell-specific marker protein vimentin abundantly and the epithelial cell-specific marker CK insignificantly (B, C) (N = 3). D) Primary and immortalized trophoblast cells express the epithelial cell-specific marker CK-7 largely and the mesenchymal cell-specific marker vimentin barely (N = 3). E) Both the primary and immortalized decidual cells express a broad amount of the decidual cell-specific marker protein prolactin and the mesenchymal cell-specific marker vimentin (N = 3). DAPI is for visualization of the cellular nucleus. Scale bar, 100 μm. CK, cytokeratin. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. AEC, amnion epithelial cells. AMC, amnion mesenchymal cells. CMC, chorion mesenchymal cells. CTC, chorion trophoblast cells. DEC, decidua cells. p, primary. hFM, human fetal membrane.

Whole-gene transcriptome analysis revealed the immortalized cell gene expression pattern is comparable to primary cells

To compare whole-genome gene expression patterns of the immortalized cells to primary cells, we performed RNA seq analysis. As shown in Fig. 4, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient for gene expression of the primary and immortalized cells detected high gene expression patterns in the AECs (R = 0.857), AMCs (R = 0.812) and CMCs (R = 0.798) (Fig. 4A-C). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was detected the highest in CTCs (R = 0.949) and DECs (R = 0.974) when comparing the primary and immortalized cells (Fig. 4D,E). Moreover, PCA of RNA seq showed clustering of the respective primary and immortalized cells, and spatial separation revealed a distinct population of cells within the fetal membranes that were different from the decidua (Supplementary Fig. S1). Differential gene expression analysis showed the following: in hFM-AEC lines (P9), 6.2% of the genes were upregulated, and 6.1% of the genes were downregulated (from 11,632 total genes); in hFM-AMC lines (P11), 5.9% of the genes were upregulated, and 5.2% of the genes were downregulated (from 11,988 total genes); in hFM-CMC cell lines (P11), 5.0% of the genes were upregulated, and 7.8% the genes were downregulated (from 11,968 total genes); in hFM-CTC lines (P8), 1.47% of the genes were upregulated, and 1.93% of the genes were downregulated (from 60,612 total genes); and in hFM-DEC lines (P15), 0.6% of the genes were upregulated, and 0.41% of the genes were downregulated (from 11,953 total genes) (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 4.

The gene expression pattern of the immortalized cells shows a high correlation with the primary origin of the cells. Gene expression pattern with RNA seq analysis for the primary and immortalized cells of each cell type. Pearson’s correlation coefficient for primary vs. immortalized cells revealed a high degree of correlation in AEC (R = 0.857), AMC (R = 0.812), and CMC (R = 0.798) (A-C), with the highest degree in CTC (R = 0.949) and DEC (R = 0.9740) (D-E) with GraphPad software. AEC, amnion epithelial cells. AMC, amnion mesenchymal cells. CMC, chorion mesenchymal cells. CTC, chorion trophoblast cells. DEC, decidua cells. p, primary. hFM, human fetal membrane.

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signalling is activated in immortalized cells

To determine the functional similarities between the primary and immortalized cell lines, we used a traditional experimental approach that has been well established in our laboratory as well as others [57] using fetal membrane cells [7, 58, 59]. For this, we induced oxidative stress in cells using CSE that is expected to induce p38MAPK activation for stress signalling, which can cause the development of senescence. As shown in Fig. 5, p38 MAPK activation (phosphorylated p38MAPK) was seen in response to oxidative stress at 6 h and 12 h after CSE treatment for both the primary and immortalized cells of all cell types (hFM-AEC at P8, hFM-AMC at P7, hFM-CMC at P7, hFM-CTC at P6 and hFM-DEC at P12). This is consistent with our prior reports on primary cells [29]. Total p38 protein expressions were also comparable in the primary and immortalized cells, regardless of the treatments for all cell types (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

p38 MAPK analysis for cellular signalling pathway activation in the immortalized cells. Western blot analysis was conducted with 20 μg of total proteins to detect oxidative stress-induced p-p38 MAPK at 6 h and 12 h of CSE treatment (1:25) by comparing the primary and immortalized cells. Comparable total p38 expression was detected in the same cell lysates. β-actin was detected as a loading control (N = 3). A total 20 μg of total proteins was used. CSE, cigarette smoke extract. AEC, amnion epithelial cells. AMC, amnion mesenchymal cells. CMC, chorion mesenchymal cells. CTC, chorion trophoblast cells. DEC, decidua cells. p, primary. i, immortalized.

The genome of immortalized cells is maintained after immortalization

Finally, we performed genomic stability testing for the chromosome and DNA analysis by comparing immortalized cells to the primary origin of the cells to see if the immortalization process made any impactful changes to the chromosome and genome of the cell lines (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Fig. S2). Fig. 6A shows the pDEC and hFM-DEC cells (P12) displayed a normal human female karyotype with G-banded chromosome analysis. Next, we performed STR DNA analysis, which is the standard for human cell line authentication, to check DNA-specific sequencing integrities in the hFM-DEC cell line by comparing them to pDEC (Fig. 6B). STR profiling analysis was developed via ATCC Standards Development Organization, ASN-0002, and a broadly recommended human cell line authentication analysis [60]. Eight core STR loci and the gender determining locus amelogenin-based STR analysis revealed 100% match between the pDEC and hFM-DEC cell line (Fig. 6B). Finally, we performed STR DNA analysis in the late passage number (more than P30) of cell lines to compare them to the early passage number (less than P10) of the cell lines in case of possible genetic drift over the passages in the immortalized cell lines (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Fig. S3, Supplementary Table S3). Fig. 6C shows, at P39, the hFM-DEC line was matched 100% to the early passage number (P7) of hFM-DEC cell line with STR analysis showing our immortalized cell lines remained authentic, making them valuable cell lines.

Figure 6.

Immortalized decidual cells maintain their genome integrity after immortalization. A) A representative image of G-banded karyotyping analysis on pDEC (P1) and hFM-DEC (P12) cells. Cytogenetic analysis showed the normal human female karyotype in 90% of the primary and in 95% of the immortalized decidual cells. B) A representative electropherogram of STR analysis of the pDEC and hFM-DEC cells. STR analysis showed a 100% match for the pDEC and hFM-DEC cells. C) The immortalized decidual cell line remained authentic for more than 30 passages. A representative electropherogram of STR analysis of early passage (P7) and later passage (P39) of the hFM-DEC cell line showing a 100% match. STR matching analyses were determined based on eight core STR loci and the gender determining locus Amelogenin. DEC, decidua cells. p, primary. hFM, human fetal membrane.

Discussion

Fetal membranes are one of the critical intrauterine tissues, performing multitudes of functions during pregnancy [61]. Besides providing structural architecture to the intrauterine cavity, various factors produced by fetal membranes help to maintain pregnancy. The feto-maternal interface created between the fetal membranes and the decidua is a major functional gatekeeper for various substances, and this function is still not fully elucidated. Although transport of materials across the feto-maternal unit may not be the prime function performed by this interface, such as the placental-decidual interface, this property membrane-decidual interface is poorly studied. Besides, membranes and decidua protect the intrauterine cavity from invading microorganisms and maternal immune cells from reaching the foetus [62–65]. Therefore, these tissues are inevitable when studying the biology of reproduction.

Multiple challenges are faced by investigators in the field of reproductive biology when conducting research using amniochorion-decidual cells. They include lack of (1) properly collected placental specimens that are not confounded by various pregnancy-related issues for isolation of primary cells; (2) protocols that provide adequate an quantity of cells for multiple experiments using cells from the same placenta; (3) protocols that will prevent cellular transitions so that a population of cells is consistent throughout the culture period; (4) protocols to generate cells lines from primary amniochorion-decidual cells; (5) availability of cell lines that can produce consistent and reproducible data without subject to subject variability; and (6) placenta for preparing primary cells routinely for researchers with no access to labour and delivery clinics who are interested in reproductive biology research. Recent advancements in organ on chip-based experiments also demand the need of multiple cell types from the same placenta to study intercellular interactions [66]. Interindividual variability also needs to be avoided in these experiments. These challenges led us to develop cell lines for the use of reproductive biology scientists who may benefit by using stable cell lines while having not to depend on placental delivery for their experiments.

We report the generation of stable cell lines of fetal membrane and decidual interface tissues that are genetically, morphologically, and functionally similar to their primary cell types. Specifically, the cells lines from five different cell types maintain the following characteristics similar to that seen in their primary cells: (1) morphologically, cells maintain their characteristic structures; (2) each cell type exhibited specific markers and culture conditions maintained the actual phenotype without any transitions; (3) cell lines are genetically stable and functionally precise where they demonstrated expected changes in response to specific stimuli; and (4) transcriptome profiles indicate no less than <83% similarity between cell lines and their parent primary cells. The subtle differences in gene expression profiles are as expected and within the limits as expected when key genes that regulate cell cycles are knocked out to create cell lines. The immortalized cells showed genomic stability without having any mutations, even after several passages as determined by STR profiling. Data from multiple passages matched 100% to their early passage/newly immortalized cells, suggesting the usefulness of these cultures for an extended number of passages and will be a great source for reproductive biology scientists who have no access to placental or primary cells.

We have not performed extensive functional studies using these cell lines to determine their signalosome and other potential markers. Based on the transcriptome profile and p38MAPK expression data, we are certain that our primary and immortalized cells provide functional similarity. Transition (EMT), migration and proliferation properties of various cell types and expression of markers facilitating various changes have been investigated using these cell lines. We have seen that cell lines behave similar to that seen in primary cells (data not shown). However, the approaches we have used for cell line creation may have impacted specific target genes and their downstream signalling. Therefore, more accurate and precise evaluation with larger biological replication will be necessary and certain variation can be expected based on specific experimental conditions. Awareness of these potential confounding effects may help users of these cell lines to interpret data properly. For this report, genome stability of the immortalized cells was analysed up to 40 passages and data were consistent. Accuracy of the passage number is important for accurate evaluation, and we emphasize this aspect while confidently presenting our data up to passage 40. Based on Hayflick’s phenomenon, cell lines may also tend to change after several passages and will show senescent behaviours [67, 68]. Higher (more than P50) passages may change the cellular characteristics and will be tested in our future studies.

In summary, we report generation of five different cell lines from human fetal membranes and decidua for various reproductive biological studies on pregnancies. Creation of genetically, phenotypically and functionally similar cell lines makes the availability of these cells abundant for various studies. Generation of this valuable tool is expected to expand studies on the feto-maternal interface and provide valuable knowledge on the function of the interface. The protocol for creating these cell lines is detailed in the manuscript, and their potential characteristics are provided. These cell lines were created and genetically characterized as per our commitment to NIH-based funding (5R01HD100729-03, and 5UG3TR003283-02); therefore, additional data and cell lines from our studies will be available at the NIH data repository.

Author contributions

ER contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data analysis, writing, editing, reviewing; RUG contributed to investigation; NDE contributed to investigation of RNA seq analysis, data analysis; MDCS contributed to investigation; RP contributed to HPV16E6E7 immortalization supervision and investigation; AH contributed to funding; RM contributed to supervision, conceptualization, writing, editing, reviewing and funding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ananth Kumar Kammala (Assistant Professorat.

Menon Laboratory) and Natasha Vora (Intern at Menon Laboratory) for their help with this project.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This study is supported by grant funds from National Institutes of Health NIH/NICHD (5R01HD100729-03 and 5UG3TR003283-02) to RM andAH.

Contributor Information

Enkhtuya Radnaa, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Perinatal Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Rheanna Urrabaz-Garza, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Perinatal Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Nathan D Elrod, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555-0144, USA.

Mariana de Castro Silva, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Perinatal Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Richard Pyles, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555-0144, USA.

Arum Han, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843-3128, USA.

Ramkumar Menon, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Perinatal Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Menon R, Richardson LS, Lappas M. Fetal membrane architecture, aging and inflammation in pregnancy and parturition. Placenta 2019; 79:40–45. PubMed PMID: 30454905; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7041999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Menon R, Moore JJ. Fetal membranes, not a mere appendage of the placenta, but a critical part of the Fetal-maternal Interface controlling parturition. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2020; 47:147–162. PubMed PMID: 32008665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malak TM, Ockleford CD, Bell SC, Dalgleish R, Bright N, Macvicar J. Confocal immunofluorescence localization of collagen types I, III, IV, V and VI and their ultrastructural organization in term human fetal membranes. Placenta 1993; 14:385–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buerzle W, Haller CM, Jabareen M, Egger J, Mallik AS, Ochsenbein-Koelble Net al. Multiaxial mechanical behavior of human fetal membranes and its relationship to microstructure. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2013; 12:747–762. PubMed PMID: 22972367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gomez-Lopez N, StLouis D, Lehr MA, Sanchez-Rodriguez EN, Arenas-Hernandez M. Immune cells in term and preterm labor. Cell Mol Immunol 2014; 11:571–581. PubMed PMID: 24954221; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4220837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacobs SO, Sheller-Miller S, Richardson LS, Urrabaz-Garza R, Radnaa E, Menon R. Characterizing the immune cell population in the human Fetal membrane. Am J Reprod Immunol 2020; e13368Epub 2020/11/05. PubMed PMID: 33145922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feng L, Allen TK, Marinello WP, Murtha AP. Roles of progesterone receptor membrane component 1 in oxidative stress-induced aging in chorion cells. Reprod Sci 2019; 26:394–403. PubMed PMID: 29783884; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6728555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Behnia F, Taylor BD, Woodson M, Kacerovsky M, Hawkins H, Fortunato SJet al. Chorioamniotic membrane senescence: a signal for parturition? 1. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Behnia F, Sheller S, Menon R. Mechanistic differences leading to infectious and sterile inflammation 3. Am J Reprod Immunol 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dutta EH, Behnia F, Boldogh I, Saade GR, Taylor BD, Kacerovsky M. Et al, Oxidative stress damage-associated molecular signaling pathways differentiate spontaneous preterm birth and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Mol Hum Reprod 2016; 22:143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Plazyo O, Schwenkel G, Garcia-Flores V, Unkel Ret al. Preterm labor in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis is characterized by cellular senescence of the chorioamniotic membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017. PubMed PMID: 28847437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirota Y, Daikoku T, Tranguch S, Xie H, Bradshaw HB, Dey SK. Uterine-specific p53 deficiency confers premature uterine senescence and promotes preterm birth in mice. J Clin Invest 2010; 120:803–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Menon R, Behnia F, Polettini J, Saade GR, Campisi J, Velarde M. Placental membrane aging and HMGB1 signaling associated with human parturition. Aging (Albany NY) 2016; 8:216–230. PubMed PMID: 26851389; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4789578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kumar D, Moore RM, Mercer BM, Mansour JM, Redline RW, Moore JJ. The physiology of fetal membrane weakening and rupture: insights gained from the determination of physical properties revisited. Placenta 2016; 42:59–73. PubMed PMID: 27238715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burzle W, Mazza E, Moore JJ. About puncture testing applied for mechanical characterization of fetal membranes. J Biomech Eng 2014; 136. PubMed PMID: 25171138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Challis JR, Smith SK. Fetal endocrine signals and preterm labor. Biol Neonate 2001; 79:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bryant-Greenwood GD, Kern A, Yamamoto SY, Sadowsky DW, Novy MJ. Relaxin and the human fetal membranes. Reprod Sci 2007; 14:42–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kendal-Wright CE, Hubbard D, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Chronic stretching of amniotic epithelial cells increases pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF/visfatin) expression and protects them from apoptosis. Placenta 2008; 29:255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kendal-Wright CE. Stretching, mechanotransduction, and proinflammatory cytokines in the fetal membranes. Reprod Sci 2007; 14:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jacobs SO, Sheller-Miller S, Richardson LS, Urrabaz-Garza R, Radnaa E, Menon R. Characterizing the immune cell population in the human fetal membrane. Am J Reprod Immunol 2021; 85:e13368Epub 2020/11/05. PubMed PMID: 33145922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garfias Y, Zaga-Clavellina V, Vadillo-Ortega F, Osorio M, Jimenez-Martinez MC. Amniotic membrane is an immunosuppressor of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunol Invest 2011; 40:183–196. PubMed PMID: 21080833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Estrada-Gutierrez G, Gomez-Lopez N, Zaga-Clavellina V, Giono-Cerezo S, Espejel-Nunez A, Gonzalez-Jimenez MAet al. Interaction between pathogenic bacteria and intrauterine leukocytes triggers alternative molecular signaling cascades leading to labor in women. Infect Immun 2010; 78:4792–4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sato BL, Collier ES, Vermudez SA, Junker AD, Kendal-Wright CE. Human amnion mesenchymal cells are pro-inflammatory when activated by the toll-like receptor 2/6 ligand, macrophage-activating lipoprotein-2. Placenta 2016; 44:69–79. PubMed PMID: 27452440; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4964608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pavan B, Fiorini S, Ferretti ME, Vesce F, Biondi C. WISH cells as a model for the "in vitro" study of amnion pathophysiology. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord 2003; 3:83–92Epub 2003/02/07. PubMed PMID: 12570726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Omere C, Richardson L, Saade GR, Bonney EA, Kechichian T, Menon R. Interleukin (IL)-6: a friend or foe of pregnancy and parturition? Evidence From Functional Studies in Fetal Membrane Cells Front Physiol 2020; 11:891. PubMed PMID: 32848846; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7397758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mogami H, Hari Kishore A, Akgul Y, Word RA. Healing of preterm ruptured Fetal membranes. Sci Rep 2017; 7:13139. PubMed PMID: 29030612; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5640674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Richardson LS, Taylor RN, Menon R. Reversible EMT and MET mediate amnion remodeling during pregnancy and labor. Sci Signal 2020; 13. PubMed PMID: 32047115; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7092701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Janzen C, Sen S, Lei MY, Gagliardi de Assumpcao M, Challis J, Chaudhuri G. The role of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human amniotic membrane rupture. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017; 102:1261–1269. PubMed PMID: 28388726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Menon R, Radnaa E, Behnia F, Urrabaz-Garza R. Isolation and characterization human chorion membrane trophoblast and mesenchymal cells. Placenta 2020; 101:139–146. PubMed PMID: 32979718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Richardson LS, Radnaa E, Urrabaz-Garza R, Lavu N, Menon R. Stretch, scratch, and stress: suppressors and supporters of senescence in human fetal membranes. Placenta 2020; 99:27–34. PubMed PMID: 32750642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jin J, Richardson L, Sheller-Miller S, Zhong N, Menon R. Oxidative stress induces p38MAPK-dependent senescence in the feto-maternal interface cells. Placenta 2018; 67:15–23. PubMed PMID: 29941169; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6023622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Loudon JA, Elliott CL, Hills F, Bennett PR. Progesterone represses interleukin-8 and cyclo-oxygenase-2 in human lower segment fibroblast cells and amnion epithelial cells. Biol Reprod 2003; 69:331–337. PubMed PMID: 12672669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meng Y, Murtha AP, Feng L. Progesterone, inflammatory cytokine (TNF-alpha), and oxidative stress (H2O2) regulate progesterone receptor membrane component 1 expression in Fetal membrane cells. Reprod Sci 2016; 23:1168–1178. PubMed PMID: 26919974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang W, Guo C, Li W, Li J, Wang W, Myatt Let al. Involvement of GR and p300 in the induction of H6PD by cortisol in human amnion fibroblasts. Endocrinology 2012; 153:5993–6002. PubMed PMID: 23125313; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3512073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sun K, Ma R, Cui X, Campos B, Webster R, Brockman Det al. Glucocorticoids induce cytosolic phospholipase A2 and prostaglandin H synthase type 2 but not microsomal prostaglandin E synthase (PGES) and cytosolic PGES expression in cultured primary human amnion cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88:5564–5571. PubMed PMID: 14602805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moore JJ, Dubyak GR, Moore RM, Vander KD. Oxytocin activates the inositol-phospholipid-protein kinase-C system and stimulates prostaglandin production in human amnion cells. Endocrinology 1988; 123:1771–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moore RM, Silver RJ, Moore JJ. Physiological apoptotic agents have different effects upon human amnion epithelial and mesenchymal cells. Placenta 2003; 24:173–180S0143400402908866 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Amand MMS, Hanover JA, Shiloach J. A comparison of strategies for immortalizing mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Methods 2016; 3:e41. PubMed PMID: 31453208; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6706133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu H, Wang L, Wang Y, Zhu Q, Aldo P, Ding Jet al. Establishment and characterization of a new human first trimester trophoblast cell line, AL07. Placenta 2020; 100:122–132. PubMed PMID: 32927240; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8237240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kniss DA. Isolation and spontaneous immortalization of trophoblast-like ED (27) cell lines. Placenta 2002; 23:100–101. PubMed PMID: 11869097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Halbert CL, Demers GW, Galloway DA. The E7 gene of human papillomavirus type 16 is sufficient for immortalization of human epithelial cells. J Virol 1991; 65:473–478. PubMed PMID: 1845902; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC240541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Demers GW, Foster SA, Halbert CL, Galloway DA. Growth arrest by induction of p53 in DNA damaged keratinocytes is bypassed by human papillomavirus 16 E7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91:4382–4386. PubMed PMID: 8183918; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC43789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sheller S, Papaconstantinou J, Urrabaz-Garza R, Richardson L, Saade G, Salomon Cet al. Amnion-epithelial-cell-derived exosomes demonstrate physiologic state of cell under oxidative stress. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0157614. PubMed PMID: 27333275; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4917104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mills AA, Yonish B, Feng L, Schomberg DW, Heine RP, Murtha AP. Characterization of progesterone receptor isoform expression in fetal membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 195:998–1003. PubMed PMID: 16893510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yamamoto A, Kumakura S, Uchida M, Barrett JC, Tsutsui T. Immortalization of normal human embryonic fibroblasts by introduction of either the human papillomavirus type 16 E6 or E7 gene alone. Int J Cancer 2003; 106:301–309. PubMed PMID: 12845665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsuruga Y, Kiyono T, Matsushita M, Takahashi T, Kasai H, Todo S. Establishment of immortalized human hepatocytes by introduction of HPV16 E6/E7 and hTERT as cell sources for liver cell-based therapy. Cell Transplant 2008; 17:1083–1094. PubMed PMID: 28863749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stoner GD, Kaighn ME, Reddel RR, Resau JH, Bowman D, Naito Zet al. Establishment and characterization of SV40 T-antigen immortalized human esophageal epithelial cells. Cancer Res 1991; 51:365–371PubMed PMID: 1703038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kao C, Hauser P, Reznikoff WS, Reznikoff CA. Simian virus 40 (SV40) T-antigen mutations in tumorigenic transformation of SV40-immortalized human uroepithelial cells. J Virol 1993; 67:1987–1995. PubMed PMID: 8383222; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC240267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yamada Y, Liao GR, Tseng CY, Tseng YY, Hsu WL. Establishment and characterization of transformed goat primary cells by expression of simian virus 40 large T antigen for orf virus propagations. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0226105Epub 20191205. PubMed PMID: 31805146; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6894772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen Y, Hu S, Wang M, Zhao B, Yang N, Li Jet al. Characterization and establishment of an immortalized rabbit melanocyte cell line using the SV40 large T antigen. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20. PubMed PMID: 31575080; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6802187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Radnaa E, Richardson LS, Sheller-Miller S, Baljinnyam T, Castro SM, Kumar Kammala Aet al. Extracellular vesicle mediated feto-maternal HMGB1 signaling induces preterm birth. Lab Chip 2021; 21:1956–1973. PubMed PMID: 34008619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Elrod ND, Jaworski EA, Ji P, Wagner EJ, Routh A. Development of poly(a)-ClickSeq as a tool enabling simultaneous genome-wide poly(a)-site identification and differential expression analysis. Methods 2019; 155:20–29. PubMed PMID: 30625385; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7291597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Richard C, Lanner C, Naryzhny SN, Sherman L, Lee H, Lambert PFet al. The immortalizing and transforming ability of two common human papillomavirus 16 E6 variants with different prevalences in cervical cancer. Oncogene 2010; 29:3435–3445. PubMed PMID: 20383192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fukuda T, Furuya K, Takahashi K, Orimoto A, Sugano E, Tomita Het al. Combinatorial expression of cell cycle regulators is more suitable for immortalization than oncogenic methods in dermal papilla cells. iScience 2021; 24:101929. PubMed PMID: 33437932; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7788094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ahuja D, Sáenz-Robles MT, Pipas JM. SV40 large T antigen targets multiple cellular pathways to elicit cellular transformation. Oncogene 2005; 24:7729–7745. PubMed PMID: 16299533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhu JY, Abate M, Rice PW, Cole CN. The ability of simian virus 40 large T antigen to immortalize primary mouse embryo fibroblasts cosegregates with its ability to bind to p53. J Virol 1991; 65:6872–6880. PubMed PMID: 1658380; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC250785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Menon R, Boldogh I, Urrabaz-Garza R, Polettini J, Syed TA, Saade GRet al. Senescence of primary amniotic cells via oxidative DNA damage. PLoS One 2013; 8:e83416. PubMed PMID: 24386195; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3873937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lavu N, Richardson L, Radnaa E, Kechichian T, Urrabaz-Garza R, Sheller-Miller Set al. Oxidative stress-induced downregulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta in fetal membranes promotes cellular senescencedagger. Biol Reprod 2019; 101:1018–1030. PubMed PMID: 31292604; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7150613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lappas M, Riley C, Lim R, Barker G, Rice GE, Menon Ret al. MAPK and AP-1 proteins are increased in term pre-labour fetal membranes overlying the cervix: regulation of enzymes involved in the degradation of fetal membranes. Placenta 2011; 32:1016–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Capes-Davis A, Reid YA, Kline MC, Storts DR, Strauss E, Dirks WGet al. Match criteria for human cell line authentication: where do we draw the line? Int J Cancer 2013; 132:2510–2519. PubMed PMID: 23136038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Menon R. Human fetal membranes at term: dead tissue or signalers of parturition? Placenta 2016; 44:1–5. PubMed PMID: 27452431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. King AE, Paltoo A, Kelly RW, Sallenave JM, Bocking AD, Challis JR. Expression of natural antimicrobials by human placenta and fetal membranes. Placenta 2007; 28:161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bonney EA, Johnson MR. The role of maternal T cell and macrophage activation in preterm birth: cause or consequence? Placenta 2019; 79:53–61. PubMed PMID: 30929747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Farine T, Parsons M, Lye S, Shynlova O. Isolation of primary human Decidual cells from the Fetal membranes of term placentae. J Vis Exp 2018; 134. PubMed PMID: 29757275; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6101051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zaga-Clavellina V, Flores-Espinosa P, Pineda-Torres M, Sosa-Gonzalez I, Vega-Sanchez R, Estrada-Gutierrez Get al. Tissue-specific IL-10 secretion profile from term human fetal membranes stimulated with pathogenic microorganisms associated with preterm labor in a two-compartment tissue culture system. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014; 27:1320–1327. PubMed PMID: 24138141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Richardson L, Kim S, Menon R, Han A. Organ-on-Chip Technology: the future of Feto-maternal Interface research? Front Physiol 2020; 11:715. PubMed PMID: 32695021; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7338764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hayflick L. The establishment of a line (WISH) of human amnion cells in continuous cultivation. Exp Cell Res 1961; 23:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hayflick L. Aging human cells. Triangle 1973; 12:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.