Abstract

Introduction

Parapharyngeal space infection may lead to severe and potentially life-threatening complications. The aim of this study was to assess the odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space using CT imaging.

Materials and Methods

Nineteen patients in mandibular odontogenic infections with abscess who underwent contrast-enhanced CT were evaluated in this study. We reviewed the location of abscess and spread of odontogenic infections to the different components of the buccal space, submandibular space, sublingual space, masticator space and parapharyngeal space using CT imaging. The location of abscess and spread of odontogenic infections were analyzed with the Pearson Chi-square test.

Results

Regarding the odontogenic infection pathway to parapharyngeal space, the masticator space (100%) was the most frequent, followed by the buccal space (85.7%), submandibular space (85.7%) and sublingual space (57.1%), while those without parapharyngeal space, the submandibular space (83.3%) was the most frequent, followed by the buccal space (75.0%), masticator space (58.3%) and sublingual space (33.3%). The masticator space was significant space in patients with/without parapharyngeal space infection (P = 0.047).

Conclusion

CT imaging could be an effective method in assessment of odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space. The odontogenic infection in masticator space tends to display spread of parapharyngeal space.

Keywords: Odontogenic infection, Fascial spaces, Parapharyngeal space, Masticator space, CT

Introduction

Deep neck infection is defined as bacterial infection in the potential spaces and fascial planes of the neck, including submandibular, lateral cervical, visceral, carotid, parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal spaces [1]. The deep neck infection is not difficult to diagnose clinically, but correct localization of the involved space for timely incision and drainage is not easy without assistance of imaging [2]. Deep neck space infection may lead to severe and potentially life-threatening complications, such as airway obstruction, mediastinitis, septic embolization, dural sinus thrombosis and intracranial abscess. The complication risk depends on the extent and anatomical site: diseases that transgress facial boundaries and spread along vertically oriented spaces (parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal and paravertebral space) have a higher risk of complications and require a more aggressive treatment compared with those confined within a nonvertically oriented space (peritonsillar, sublingual, submandibular, parotid and masticator space) [3].

Parapharyngeal space is a potential space extending from the skull base superiorly to the hyoid bone inferiorly [4]. The parapharyngeal space abscesses are deep-space neck infections that are associated with significant morbidity and, rarely, mortality if not promptly diagnosed and treated [5].

Odontogenic infections represent a common clinical problem in patients of all ages. The presence of teeth enables the direct spread of inflammatory products from dental caries, trauma and/or periodontal disease into the maxilla and mandible [6, 7]. Although odontogenic infections are usually confined to the alveolar ridge vicinity, they can spread into deep fascial spaces [8, 9]. The odontogenic infections may spread into the adjacent anatomical spaces along the contiguous fascial planes, leading to involvement of multiple spaces which can progress to life-threatening situations [10].

Computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging clearly demonstrated different pathways of the spread of odontogenic infection into the fascial spaces [11–14]. However, to our knowledge, few reports have been published on parapharyngeal space spread of odontogenic infections using CT. The aim of this study was to assess the odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space using CT imaging.

Materials and Methods

Patients Population

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital (ECNG-R-318), and all patients provided written informed consent. Nineteen patients [5 men and 14 women; mean age, 66.9 years (range 42–99 years)] in mandibular odontogenic infections with abscess who underwent contrast-enhanced CT at our hospital between November 2018 and April 2020 were evaluated in this study. The diagnosis of odontogenic infection was diagnosed from the clinical course of patient. Surgical drainage and/or tooth extraction of origin of infection were performed in all patients after contrast-enhanced CT. Clinical signs and symptoms of all cases were reduced after antibiotic treatment.

Contrast-Enhanced CT

CT imaging was performed with a 16-multidetector CT scanner (Aquilion TSX-101A; Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) using oral and maxillofacial protocol at our hospital: tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current, 150 mAs; field of view, 240 × 240 mm; rotation time, 0.50 s. The protocol consisted of axial acquisition (0.50 mm) with axial, coronal and sagittal multiplanar reformation (MPR) images. The patients received contrast-enhanced CT with non-ionic iodine for head and neck lesions. One non-ionic contrast media was used; Iohexol 300 mg I/mL (Omunipaque 300 Syringe, Daiichi-Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan). Contrast medium was administered as an injection of 100 mL at a rate of 1.0 mL/s (Autoenhance A-250, Nemoto-Kyorindo, Tokyo, Japan).

Image Analysis

The two oral and maxillofacial radiologists independently reviewed the location of abscess and spread of odontogenic infections to the different components of the buccal space, submandibular space, sublingual space, masticator space and parapharyngeal space using CT imaging, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

The mean age in patients with/without parapharyngeal space were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney U test. The sex, location of abscess and spread of odontogenic infections were analyzed with the Pearson Chi-square test. The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan) with a 5% significance level.

Results

Table 1 shows odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space using CT imaging. Of all 19 patients in mandibular odontogenic infections with abscess, especially location of abscess, the masticator space (8 patients: 42.1%) was the most frequent, followed by the sublingual space (4 patients: 21.1%, Fig. 1), submandibular space (4 patients: 21.1%, Fig. 2), buccal space (3 patients: 15.8%) and parapharyngeal space (0 patient: 0%). Regarding those in spread of odontogenic infections, the submandibular space (16 patients: 84.2%) was the most frequent, followed by the buccal space (15 patients: 78.9%), masticator space (14 patients: 73.7%), sublingual space (8 patients: 42.1%) and parapharyngeal space (7 patients: 36.8%).

Table 1.

Odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space using CT imaging

| Patient characteristics | Parapharyngeal space | Total (n = 19) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With (n = 7) | Without (n = 12) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.773 | |||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 69.4 ± 19.8 | 65.4 ± 11.2 | 66.9 ± 14.5 | |

| Range | 52–99 | 42–77 | 42–99 | |

| Sex | 0.865 | |||

| Men | 2 (28.6%) | 3 (25.0%) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Women | 5 (71.4%) | 9 (75.0%) | 14 (73.7%) | |

| Location of abscess | ||||

| Buccal space | 0 (0%) | 3 (25.0%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0.149 |

| Submandibular space | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (25.0%) | 4 (21.1%) | 0.581 |

| Sublingual space | 2 (28.6%) | 2 (16.7%) | 4 (21.1%) | 0.539 |

| Masticator space | 4 (57.1%) | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 0.311 |

| Parapharyngeal space | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Spread of odontogenic infections | ||||

| Buccal space | 6 (85.7%) | 9 (75.0%) | 15 (78.9%) | 0.581 |

| Submandibular space | 6 (85.7%) | 10 (83.3%) | 16 (84.2%) | 0.891 |

| Sublingual space | 4 (57.1%) | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 0.311 |

| Masticator space | 7 (100%) | 7 (58.3%) | 14 (73.7%) | 0.047 |

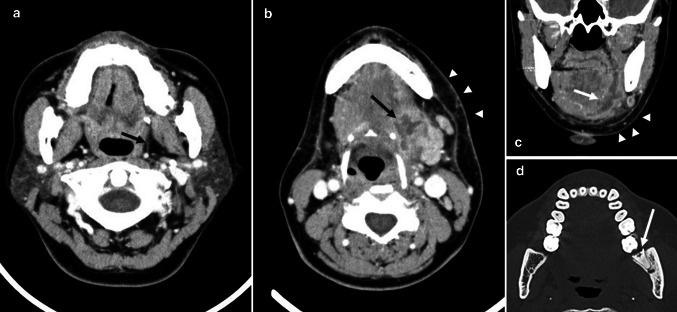

Fig. 1.

A 47-year-old woman with odontogenic infections. a Axial contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates no spread of odontogenic infections in parapharyngeal space (arrow). b Axial contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates abscess in sublingual space (arrow) and the spread of odontogenic infections in submandibular space (arrowheads). c Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates abscess in sublingual space (arrow) and the spread of odontogenic infections in submandibular space (arrowheads). d Axial bone-algorithm CT image demonstrates pericoronitis (arrow)

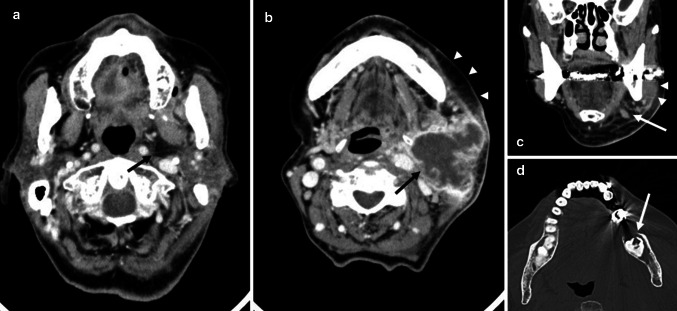

Fig. 2.

A 99-year-old woman with odontogenic infections. a Axial contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates the spread of odontogenic infections in parapharyngeal space (arrow). b Axial contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates abscess in submandibular space (arrow) and the spread of odontogenic infections in buccal space (arrowheads). c Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates the spread of odontogenic infections in masticator space (arrowheads) and submandibular space (arrow). d. Axial bone-algorithm CT image demonstrates pericoronitis (arrow)

Regarding location of abscess for 7 patients with parapharyngeal space infection, the masticator space (4 patients: 57.1%) was the most frequent, followed by the sublingual space (2 patients: 28.6%), submandibular space (1 patient: 14.3%) and buccal space (0 patient: 0%), while the masticator space (4 patients: 33.3%) was the most frequent in 12 patients without parapharyngeal space infection, followed by the buccal space (3 patients: 25.0%), submandibular space (3 patients: 25.0%) and sublingual space (2 patients: 16.7%).

Regarding spread of odontogenic infections for 7 patients with parapharyngeal space infection, the masticator space (7 patients: 100%) was the most frequent, followed by the buccal space (6 patients: 85.7%), submandibular space (6 patients: 85.7%) and sublingual space (4 patients: 57.1%), while the submandibular space (10 patients: 83.3%) was the most frequent in 12 patients without parapharyngeal space infection, followed by the buccal space (9 patients: 75.0%), masticator space (7 patients: 58.3%) and sublingual space (4 patients: 33.3%). The masticator space was significant space in patients with/without parapharyngeal space infection (P = 0.047).

Discussion

We assessed the odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space using CT imaging, and indicated that CT imaging could be an effective method in assessment of odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space, and the odontogenic infection in masticator space tend to display spread of parapharyngeal space.

Ariji et al. [11] showed that CT and MR imaging clearly demonstrated different pathways of the spread of odontogenic infection into the submandibular space, which influenced the manifestation of clinical symptoms. Bassiony et al. [13] indicated ultrasonography could be considered to be an effective method in detecting and staging spread of odontogenic infections to the superficial fascial spaces, however, it might be difficult to detect deep fascial space involvements. In this study, we assessed the odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space using CT imaging. CT imaging could be an effective method in assessment of odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space.

Regarding fascial space spread of odontogenic infections, Shakya et al. [10] reported that in subjects with single space odontogenic infections, submandibular space was most commonly affected (44.26%) followed by buccal space (27%). In subjects with multiple space infections, submandibular space (30.19%) was most frequently involved followed by buccal space (17.92%). Bassiony et al. [13] showed that in the involved fascial spaces spread of odontogenic infections, the buccal space was the most commonly involved space (31%). The second most commonly involved fascial space was the submandibular space (23.8%). Moghimi et al. [9] indicated that infection of maxillary teeth most commonly spread to the buccal space, whereas infection originating in the mandible mostly spread to the submandibular, pterygomandibular and buccal spaces. In this study, regarding mandibular odontogenic infections with abscess, the submandibular space (84.2%) was the most frequent in spread of odontogenic infections, followed by the buccal space (78.9%), masticator space (73.7%), sublingual space (42.1%) and parapharyngeal space (36.8%). However, the masticator space (42.1%) was the most frequent in location of abscess, followed by the sublingual space (21.1%), submandibular space (21.1%), buccal space (15.8%) and parapharyngeal space (0%).

In this study, regarding spread of odontogenic infections with parapharyngeal space infection, the masticator space (100%) was the most frequent, followed by the buccal space (85.7%), submandibular space (85.7%) and sublingual space (57.1%), while spread of odontogenic infections without parapharyngeal space infection, the submandibular space (83.3%) was the most frequent, followed by the buccal space (75.0%), masticator space (58.3%) and sublingual space (33.3%). Schuknecht et al. [12] indicated that medial masticator space abscesses tend to display early extra-spatial parapharyngeal space and/or soft palate extension. We showed that the masticator space was significant space in patients with/without parapharyngeal space infection, and consider that parapharyngeal space infection is deeply related to masticator space.

The limitations of this study were as follows: the number of patients in mandibular odontogenic infections with abscess was too small, and logistic multivariate regression analysis was not used to determine the relationship between parapharyngeal space infection and other spaces. Therefore, further research is necessary to validate these results.

Conclusion

This study assessed the odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space using CT imaging. CT imaging could be an effective method in assessment of odontogenic infection pathway to the parapharyngeal space. The odontogenic infection in masticator space tends to display spread of parapharyngeal space.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP 18K09754.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The study was approved by institutional review board. Informed written consent was obtained from the patients for participation in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rzepakowska A, Rytel A, Krawczyk P, Osuch-Wojcikiewicz E, Widlak I, Deja M, Niemczyk K. The factors contributing to efficiency in surgical management of purulent infections of deep neck spaces. Ear Nose Throat J. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0145561319877281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang B, Gao BL, Xu GP, Xiang C. Images of deep neck space infection and the clinical significance. Acta Radiol. 2014;55(8):945–951. doi: 10.1177/0284185113509093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maroldi R, Farina D, Ravanelli M, Lombardi D, Nicolai P. Emergency imaging assessment of deep neck space infections. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012;33(5):432–442. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sichel JY, Dano I, Hocwald E, Biron A, Eliashar R. Nonsurgical management of parapharyngeal space infections: a prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(5):906–910. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200205000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simard RD, Socransky S, Chenkin J. Transoral point-of-care ultrasound in the diagnosis of parapharyngeal space abscess. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(1):70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertossi D, Barone A, Iurlaro A, Marconcini S, Santis DD, Finotti M, Procacci P. Odontogenic orofacial infections. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(1):197–202. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mardini S, Gohel A. Imaging of odontogenic infections. Radiol Clin N Am. 2018;56(1):31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogle OE. Odontogenic infections. Dent Clin N Am. 2017;61(2):235–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moghimi M, Baart JA, Karagozoglu KH, Forouzanfar T. Spread of odontogenic infections: a retrospective analysis and review of the literature. Quintessence Int. 2013;44(4):351–361. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a29150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shakya N, Sharma D, Newaskar V, Agrawal D, Shrivastava S, Yadav R. Epidemiology, microbiology and antibiotic sensitivity of odontogenic space infections in central India. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2018;17(3):324–331. doi: 10.1007/s12663-017-1014-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariji Y, Gotoh M, Kimura Y, Naitoh M, Kurita K, Natsume N, Ariji E. Odontogenic infection pathway to the submandibular space: imaging assessment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31(2):165–169. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuknecht B, Stergiou G, Graetz K. Masticator space abscess derived from odontogenic infection: imaging manifestation and pathways of extension depicted by CT and MR in 30 patients. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(9):1972–1979. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassiony M, Yang J, Abdel-Monem TM, Elmogy S, Elnagdy M. Exploration of ultrasonography in assessment of fascial space spread of odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(6):861–869. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogura I, Iizuka N, Ishida M, Sawada E, Kaneda T. Spread of odontogenic infections in the elderly: prevalence and characteristic multidetector CT findings. Int J Diagn Imaging. 2017;4(1):28–33. doi: 10.5430/ijdi.v4n1p28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]