Abstract

Purpose

To compare the clinical efficacy of classical inferior alveolar nerve block (CIANB) and Vazirani–Akinosi (VA) injection technique in patients indicated for bilateral mandibular premolar teeth extraction for orthodontic treatment.

Methods

This split-mouth comparative study was conducted on 20 patients randomly selected for bilateral extraction of mandibular premolar indicated for orthodontic treatment to receive CIANB and VA injection technique alternatively. The clinical parameters evaluated were pain during injection, onset of anesthesia, duration of anesthesia, quality of anesthesia, nerve anesthetized with single nerve block, need for re-injection and frequency of positive aspiration.

Results

No statistically significant differences were observed regarding the onset of anesthesia, duration of anesthesia, quality of anesthesia, nerves anesthetized with single nerve block and need for re-injection. However, pain experienced during injection was statistically significant and was lesser in VA technique than CIANB. Positive aspiration was not found in both the injection techniques.

Conclusion

VA technique showed a statistically significant difference in terms of less pain experienced during injection than CIANB. However, though not significant, VA technique was more clinically superior over the CIANB in terms of duration of anesthesia, quality of anesthesia and the need for re-injection. Also in this study, there were no complications associated with any of the injection techniques and the prevalence of positive aspiration was not found in both the techniques.

Introduction

Neuroregional anesthesia was first achieved in the mandible by injecting a solution of cocaine, in the vicinity of the mandibular foramen by William S. Halstead and Richard J. Hall in November 1884. Since that revolutionary injection, dentists have possessed a remarkable way of delivering invasive dental treatment procedures in a pain-free manner. The most commonly used drugs in dentistry are anesthetics which are injected before any painful procedure. Achieving a predictable and effective outcome requires a series of specific conditions to be met. The clinician’s knowledge and ability in addition to anatomic and pharmacological variability are all the important factors that play a critical role [1]. Since pain control is one of the most important concerns to both the dentists and patients during dental treatment, dentists usually use IANB, which was first introduced by Jorgensen and Hayden in 1967, for mandibular anesthesia [2].

In dental practice, CIANB is a routinely used injection technique which is administered in children and adults who are undergoing exodontia, endodontic procedures, minor oral surgical procedures, etc. [3]. However, it sometimes fails to induce an acceptable level of anesthesia because it relies on the presence of certain anatomical landmarks—the coronoid notch, occlusal plane and pterygomandibular raphe. Anatomical variations in shape and size of the mandible and the position of the mandibular foramen relative to the occlusal plane may make accurate localization of the mandibular foramen difficult, thereby contributing the reported failure of up to 15% of the inferior alveolar nerve block [4]. Also, while performing a CIANB, dental professional encounters a series of problems such as pain during injection, non-cooperation from the patient during intraoral approach, longer duration of onset of action of anesthesia, post-injection trismus and limited mouth opening as a result of dentoalveolar abscess or space infection [3]. Another disadvantage of CIANB is the high incidence of positive aspiration and intravascular injection, i.e., 10% to 15% because of the proximity of injection site to the neurovascular bundle. And sometimes, difficulties may be experienced in edentulous patients in cases where the raphe is not prominent and particularly in cases where mouth opening is limited [5].

To overcome the difficulties observed in achieving CIANB, various methods of anesthesia have been suggested which claims to be superior over the conventional inferior alveolar nerve block. By using an alternative technique known as VA technique, anesthesia of inferior alveolar nerve, long buccal and lingual nerve branches is achieved [6].

VA technique was introduced earlier in 1960, by Vazirani and later a similar technique was described by Akinosi in 1977. So, this technique was renamed as VA technique. It is a closed-mouth intraoral tuberosity approach where a bolus of local anesthetic is deposited into the superior portion of the pterygomandibular space where all the three branches of the mandibular nerve are anesthetized. It has the advantages of easy injection, rapid onset of action of anesthesia, less painful injection, better patient acceptance and less complication and can be used in apprehensive patients, children and patients with trismus due to space infections [7–9]. Patients with severe gagging problems who cannot tolerate conventional inferior alveolar nerve block can be successfully given closed-mouth VA injection without provoking any retching. Also, this technique permits the patients to concentrate on clenching their teeth during injection. It not only helps to facilitate the patient’s anti-nausea swallowing behavior, but also takes their minds off the procedure. This displacement activity combined with the reduction in tactile sensation following anesthesia helps to prevent gagging [10].

Various studies have been done in order to compare the efficacy of CIANB block and VA technique. However, in some studies, it was concluded with the superiority of CIANB over VA technique except for patients with limited mouth opening [11–13]. In a few other studies, it was found that the anesthetic efficacy of VA technique was superior or similar to that of CIANB [4, 9, 12].

Hence, this study attempts to compare the clinical efficacy of CIANB and VA technique in patients indicated for bilateral mandibular premolar teeth removal for orthodontic treatment.

Materials and Methods

A total of 20 patients presenting to our department participated in the study. Inclusion criteria were patients between 14 and 30 years of age, good systemic health and undergoing extraction of mandibular premolar teeth for orthodontic reason. Exclusion criteria were patients with systemic ailments, pregnancy and lactation, uncooperative and mentally retarded, and allergy to local anesthetic solution.

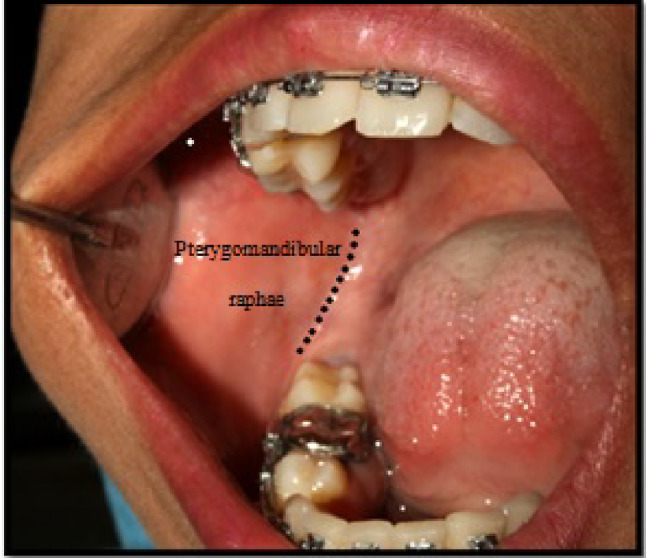

Informed consent was taken from the patients. All the patients were assigned randomly to one of the two groups. In the first session, the patients randomly received the CIANB or VA technique in one side of the oral cavity. One week later, the same patient received the other technique which was not received in the first session. In CIANB technique, the patient was positioned in semi-supine and asked to open the mouth wide to permit greater visibility of and access to the injection site. The injection site for this technique was the soft tissue covering the medial surface of the ramus at the lateral side of the pterygomandibular raphae and the external oblique ridge. The syringe was positioned between the premolars from the opposite site. Aspiration was carried out and 1.8 ml of local anesthesia with 2% lignocaine hydrochloride was injected slowly. Buccal nerve block was given at the mucous membrane distal and buccal to the most distal molar teeth in the arch (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

Technique for classical inferior alveolar nerve block

Fig. 2.

Landmarks for classical inferior alveolar nerve block technique

Fig. 3.

Position of needle for classical inferior alveolar nerve block

In VA technique, the patient was positioned in semi-supine and asked to close the mouth into maximum intercuspation. The intraoral landmarks for this technique were the bone of the medial surface of the mandibular ramus, maxillary tuberosity and mucogingival junction of the maxillary third or second molar. With the mouth closed, the needle was aligned parallel to the occlusal plane and positioned at the level of the mucogingival junction of the maxillary molars. The bevel of the needle was oriented away from the bone and then inserted into the buccal mucosa at the established height and then advanced posteriorly and slightly laterally without contacting the medial surface of the bone of the mandibular ramus unlike the inferior alveolar nerve block. The needle is inserted to a depth of about 25–30 mm and following negative aspiration, 1.8 ml of local anesthesia with 2% lignocaine hydrochloride was injected slowly (Figs. 4 and 5). All the procedures were performed by one surgeon.

Fig. 4.

Vazirani–Akinosi closed-mouth technique

Fig. 5.

Technique for Vazirani–Akinosi nerve block

The following clinical parameters were evaluated:

Pain during injection: pain was assessed by using visual analogue scale

0 (No Pain) The patients feels well.

1–2 (Mild pain) The patient experiences hurt a little bit but he or she doesn’t feel the pain.

3–4 (Moderate pain) The patient experiences hurt a little more but he or she feels the pain.

5–6 (Severe pain) The patient is more distracted and he or she feels the pain but the procedure can be carried out.

7–8 (Very severe pain) The patient forces the operator to stop the procedure.

If the patient was confused with the pain score, the highest score only was documented.

-

(2)

Time of onset of lip anesthesia: Onset of anesthesia was evaluated from the time of injection till the appearance of numbness of lip.

-

(3)

Duration of anesthesia: The duration of anesthesia was observed till the lip anesthesia wears off completely and the patients were observed in the department only.

-

(4)

Nerves anesthetized with a single nerve block: Anesthesia for all the three branches of the mandibular nerve was evaluated subjectively by questioning the patient about altered tongue sensation, tingling and numbness and objectively, and it was evaluated by probing with moons probe in the lingual gingiva and the buccal gingival sulcus opposite the mandibular second molar.

-

(5)

Quality of anesthesia: It was assessed as per the eight rating scale:

Successful: No pain throughout the procedure

Successful: Some pain during the procedure but re-injection is not necessary after the beginning of the procedure

Successful: Pain during the procedure after the first injection but no pain after the second injection.

Limited success: Pain during the procedure beginning after the first injection. Pain also during the procedure after the second injection, but the surgery completed without the third injection.

Limited success: Pain during the procedure beginning after two injections, but the surgery completed without the third injection.

Failure: Pain during the procedure beginning after the first injection. Pain also during after the second injection. Third injection required.

Failure: Pain during procedure beginning after two injections. Third injections required.

Failure: No anesthesia after two injections. Third injection is required or treatment suspended.

In the first session, if the local anesthetic technique used fails, it was documented as failures for that particular injection technique and the study on the opposite site was carried out using alternative local anesthetic technique and findings were documented. Then, extraction site failure will be completed using alternative technique on later date.

-

(6)

Need for re-injection: If patient feels any pain or discomfort which is unbearable a supplementary injection was given with the same technique as performed.

After completion of the procedure, postoperative instructions were given for all the patients and were instructed to call and inform when the lip anesthesia wears off completely. One week after the first procedure, patients were again recalled for extraction of another side in which alternate injection technique was performed with the same procedures and all the parameters were documented from step 1 to 6.

Results

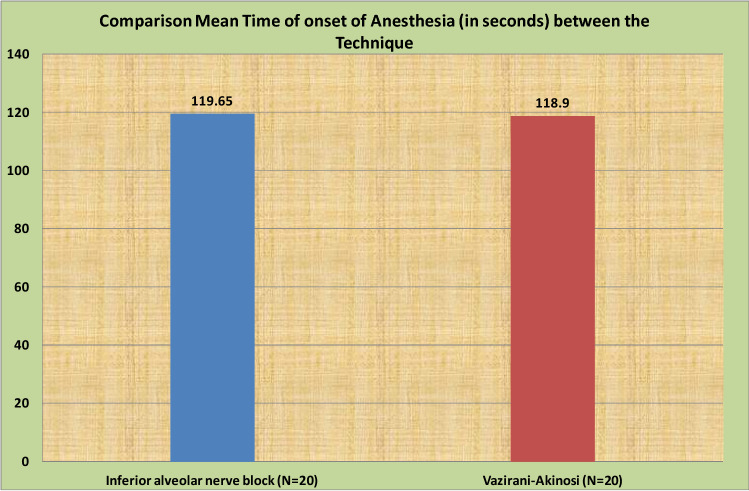

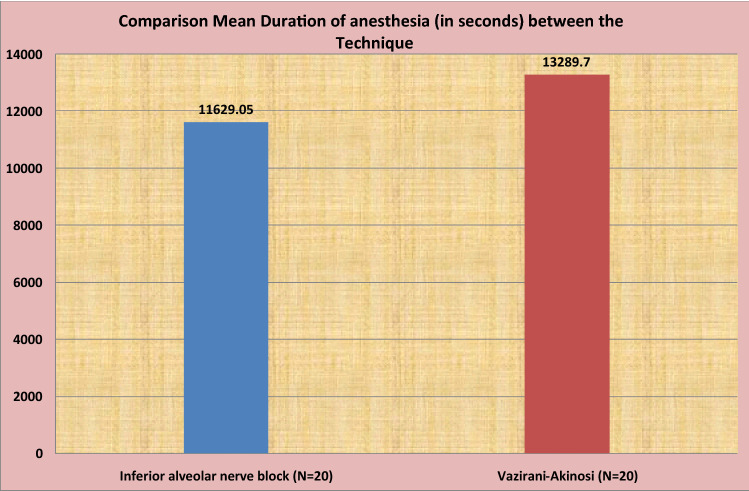

Results were calculated using Chi-square (χ2) test and Mann–Whitney U test. The “p” value of less than 0.05 was accepted as indicating statistical significance. Data analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, V 10.5) package. A total of 20 patients (8 males and 12 females) were enrolled in the study. The values for pain during injection, time of onset of anesthesia, duration of anesthesia, nerves anesthetized with single nerve block, quality of anesthesia and need for re-injection and positive aspiration were compared and evaluated and are shown in the following tables and Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 respectively. Pain score during injection for both the injection techniques was measured according to the visual analogue scale, categorized under: no pain (0), mild pain (1–2), moderate pain (3–4), severe pain (5–6) and very severe pain (7–8). Out of total of 20 CIANB injections, 3 (15%) patients experienced no pain, 8 (40%) patients experienced mild and 9 (45%) patients experienced moderate pain, whereas in VA technique, 8 (40%) patients experienced no pain, 12 (60%) patients experienced mild pain and none of the patients experienced moderate pain. The p value using Chi-square test is 0.002. So, the result was found to be statistically significant. None of the patients experienced severe and very severe pain for both the injection techniques (Table 1). Time of onset of anesthesia for CIANB was 2 min and the onset of anesthesia for VA technique was found to be 1.98 min. The p value using Mann–Whitney U test was 0.967. There was not much difference in the onset of anesthesia in both the techniques. So, the result is not statistically significant (Table 2). The duration of anesthesia was recorded from the onset of action of anesthesia till the lip anesthesia wears off. For CIANB, the duration of anesthesia was 3.23 h, and for VA technique, it was 3.69 h. The p value using Mann–Whitney U test was 0.07. So, the duration of anesthesia was not statistically significant for both the techniques. However, the duration of anesthesia in VA technique was clinically longer than the CIANB by 46 min though this was statistically not significant (Table 3).

Fig. 6.

Distribution of pain during injection for both the injection

Fig. 7.

Comparison of mean time of onset of anesthesia (in seconds) between the two injection techniques

Fig. 8.

Comparison of mean duration of anesthesia (in seconds) between the two injection techniques

Fig. 9.

Distribution of nerves anesthetized with single nerve block for both the two injection techniques

Fig. 10.

Distribution of quality of anesthesia for both the techniques

Fig. 11.

Distribution of need for re-injection for both the techniques

Table 1.

Pain experienced during injection

| Technique | Pain during injection | Total | χ2 value* | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | ||||

| Inferior alveolar nerve block | 3 | 8 | 9 | 20 | 12.073 | 0.002 |

| 15.0% | 40.0% | 45.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Vazirani–Akinosi | 8 | 12 | 0 | 20 | ||

| 40.0% | 60.0% | .0% | 100.0% | |||

| Total | 11 | 20 | 9 | 40 | ||

| 27.5% | 50.0% | 22.5% | 100.0% | |||

*Chi-square test

Table 2.

Time of onset of anesthesia (in seconds)

| Technique | N | Mean | SD | Median | Min. | Max. | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior alveolar nerve block | 20 | 119.65 | 71.289 | 107.50 | 50 | 370 | 0.967 |

| Vazirani–Akinosi | 20 | 118.90 | 37.828 | 122.00 | 63 | 200 |

*Mann–Whitney U test

Table 3.

Duration of anesthesia (in seconds)

| Technique | N | Mean | SD | Median | Min. | Max. | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior alveolar nerve block | 20 | 11,629.05 | 2537.525 | 11,531.00 | 7345 | 17,350 | 0.079 |

| Vazirani–Akinosi | 20 | 13,289.70 | 3233.428 | 13,428.50 | 7570 | 19,493 |

*Mann–Whitney U test

Regarding nerves anesthetized with single nerve block, in CIANB, 90% of inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia, 90% of lingual nerve anesthesia was achieved with single injection. 100% of buccal nerve anesthesia achieved with buccal nerve block, whereas in VA technique, 100% of inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia, 100% of lingual nerve anesthesia and 95% of buccal nerve anesthesia were achieved with single injection. On comparing both the techniques, the p value for inferior alveolar nerve anesthesia is 0.147, the p value for lingual nerve anesthesia is 0.147 and the p value for buccal nerve block anesthesia is 3.11. Therefore, it showed no statistically significant difference in all the three nerves anesthetized with single injection in both the techniques (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nerves anesthetized with single nerve block

| Technique | Nerves anesthetized with single injection | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior alveolar nerve | Lingual nerve | Long buccal nerve | |

| Classical Inferior alveolar nerve block technique | 18 | 18 | 20 |

| 90.0% | 90.0% | 100.0% | |

| Vazirani–Akinosi technique | 20 | 20 | 19 |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 95.0% | |

| χ2 value* | 2.11 | 2.11 | 1.03 |

| p value | 0.147 | 0.147 | 3.11 |

*Chi-square test

Quality of anesthesia did not differ significantly between the two techniques. The p value using Chi-square test was 0.312 which was statistically insignificant. The quality of anesthesia achieved with VA technique was more clinically successful though it was not statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Quality of anesthesia

| Quality of anesthesia | Total | χ2 value* | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No pain after the first injection | Some pain after the first injection | No pain after the second injection | Some pain after the second injection | ||||

| Inferior alveolar nerve block | 9 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 3.571 | 0.312 |

| 45.0% | 45.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Vazirani–Akinosi | 12 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 20 | ||

| 60.0% | 25.0% | 15.0% | .0% | 100.0% | |||

| Total | 21 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 40 | ||

| 52.5% | 35.0% | 10.0% | 2.5% | 100.0% | |||

*Chi-square test

Regarding the need for re-injection, CIANB showed a difference of 15% of re-injection needed when compared with VA injection technique, whereas only 5% of difference showed no requirement of re-injection. On comparing these two injection techniques, the p value using Chi-square test was 0.15 which was not statistically significant. But clinically, CIANB showed more re-injection needed compared with VA technique (Table 6). In our study, none of the injections showed positive aspiration in both the injection techniques.

Table 6.

Need for re-injection

| Need for re-injection | Total | χ2 value* | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Classical Inferior alveolar nerve block | 4 | 16 | 20 | 2.06 | 0.151 |

| 20.0% | 80.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Vazirani–Akinosi technique | 1 | 19 | 20 | ||

| 5.0% | 95.0% | 100.0% | |||

*Chi-square test

Discussion

Local anesthesia is essential for pain-free dentistry though intraoral injections are often considered painful and a source of anxiety for many patients. Anesthesia for mandibular nerve plays a key role in performing various surgical procedures in the mandible which may be achieved by standard CIANB, VA technique and Gow-Gates technique [14, 15]. IANB is a routine injection procedure used in dental practice. Failures to achieve satisfactory levels of anesthesia often occur mostly because of anatomical variations or faulty technique [3, 16]. Sometimes, difficulties may also be experienced in edentulous patients where the raphae are not prominent and particularly in cases where mouth opening is limited. Anatomical variations in the shape and size of the mandible may make accurate location of the mandibular fossa difficult. The width of the ascending rami and their divergence determine the position of the mandibular foramen which varies from one individual to another. In addition, a number of several factors like inadequate dosage of anesthetic solution, presence of supplementary or accessory innervations also accounts for an increase in the failure of CIAN anesthesia [5]. As a result of these, a variety of injection techniques have been suggested for mandibular anesthesia as an attempt to overcome these drawbacks of CIANB. As stated by Bennett CR, VA technique or closed-mouth technique, which can be called as the tuberosity approach to the mandibular nerve, often relies on a minimum number of bony landmarks and has variable depth of needle penetration due to variations in soft tissue which may be less successful than the CIANB [17]. However, JO Akinosi stated that VA technique has an approximately equal success rate to conventional inferior alveolar nerve block. This technique of injection has many advantages which include increased rate of onset of anesthesia, less pain of injection, decreased psychological stress on anxious patients and ease of administration and in individuals with large tongue and buccal fat pad obstructing the view of the anatomical landmark for the administration of inferior alveolar nerve block [5, 18]. Also, P. Donkor and J. Wong reported the superiority of VA technique in apprehensive patients, children, trismus and patients with exaggerated gag reflex and added that clenching of teeth during the injection not only helped to facilitate the patients anti-nausea swallowing behavior but also took their minds off the procedure [10, 19]. However, in our current study, none of the patients experienced gag reflex. In our study, we evaluated the clinical efficacy of CIANB in comparison with VA technique (Table 6).

Patients are more comfortable not opening their mouth during injection and it would be less painful if the needle is injected into relaxed tissue which aids the advantage of VA technique [6, 20]. Sthitaprajna Lenka et al. reported that CIANB had greater incidence of pain with respect to Gow-Gates and Akinosi technique.3In a study performed by Sobhan Mishra et al., subjects in the direct conventional group experienced more pain during injection than the subjects in the VA group which can be attributed to the 26-gauge needle used for VA technique which has smaller dimensions used than the 24 gauge needle used for the direct conventional technique [7]. Todorovic et al. found no significant difference among the three methods of CIANB in terms of pain during injection [21]. In our study, subjects with VA group reported to be less painful during injection when compared with the subjects in CIANB. Three (15%) patients experienced no pain, 8 (40%) patients experienced mild and 9 (45%) patients experienced moderate pain in CIANB, whereas in VA technique, 8 (40%) patients experienced no pain, 12 (60%) patients experienced mild pain and none of the patients experienced moderate pain. So, a significant difference was noted between the two injection techniques in terms of pain during injection. The needle gauge used in our present study was standardized to 26 gauges for both the injection techniques. Studies also reported that VA technique seems to be less painful than CIANB [6, 20]. The reason can be attributed to the less pain experienced by the subjects in VA technique because of the divergence of the medial pterygoid muscle from ramus to the lateral pterygoid muscle giving greater width of the pterygomandibular space superiorly hence reducing the chances of needle penetrating into the medial pterygoid muscles [6, 7]. Goldberg et al. found that in the conventional method needle insertion caused moderate pain in 22–25% and severe pain in 0–2% of the patients [12]. In a study done by Donkor, Wong and Punnia-Moorthy, it was found that females in the conventional group reported higher pain scores than females in the closed-mouth injection group [10, 22]. Nanjappaetal, also found higher mean pain during injection in classical group than Gow-Gates technique [1]. Martinez-Gonzalez et al. also found that subjects in the Akinosi group experienced less pain during needle puncture than that of the conventional mandibular nerve block but pain during the dental procedure was found to be practically same in both the techniques [23].

Many studies confirmed that the onset of anesthesia was recorded to be faster in VA technique than the CIANB [4, 5, 14, 17, 24]. This may be due to the needle position which is close to the anatomic location of these nerves and local anesthetic solution encountering them through diffusion and/or gravity. Additionally, VA technique also avoided the possible variable position of the mandibular foramen [14]. However, many other studies also reported rapid onset of anesthesia in CIANB than that of VA technique [25]. This may be due to the anesthetic solution being deposited higher in the pterygomandibular space in the Akinosi technique resulting in inadequate perfusion of the inferior alveolar nerve [6, 11, 12, 21–23]. Steven Goldberg et al. also found that Gow-Gates and Vazirani–Akinosi resulted in a statistically slower onset of pulpal anesthesia when compared to inferior alveolar nerve block [12]. But in our case, the onset of anesthesia was found to be almost similar when compared with CIANB (2 min mean) and VA technique (1.98 min mean).

In a study done by Martinez et al., the duration of anesthesia was effectively longer in direct conventional technique than VA technique though it was not statistically significant [23]. Todorovic et al. also reported that the duration of anesthesia was statistically insignificant among CIANB, Gow-Gates technique and VA injection technique respectively [21]. In our present study, the duration of anesthesia was recorded from the onset of action of anesthesia till the lip anesthesia wears off. So, for CIANB it was 3.23 h, and for VA technique, it was 3.69 h. The difference, however, was not statistically significant (p value 0.07). But clinically, VA technique showed longer duration of anesthesia by 46 min from CIANB. This may be due to the large diameter of the nerve fibers present in the upper portion of the pterygomandibular space injected during VA technique. So, it takes greater time to wear off the anesthesia in this technique. This supports the study done by Sthitaprajna Lenka et al., where Gow-Gates technique showed more duration of anesthesia followed by VA and CIANB respectively [3]. In another study by Ravinder Solanki et al., the duration of action of anesthesia was almost same for all the three injection techniques, i.e., Gow-Gates, VA and CIANB, VA technique being the technique providing longest duration of anesthesia [26].

Quality of anesthesia was assessed as per the rating scale described by Allen L. Sisk in patient’s response during the extraction procedure [4]. In our study, it did not differ significantly between the two injection techniques. In CIANB, 45% of injections showed no pain during procedure after the first injection, 45% showed some pain after the first injection, 5% showed no pain after the second injection and 5% showed some pain after the second injection. In VA technique, 60% of injections showed no pain after the first injection, 25% showed some pain after the first injection, 15% showed no pain after the second injection and 0% showed some pain after the second injection. On comparing, the p value using Chi-square test was 0.312 which was statistically insignificant. But, there was a difference of 15% in the pain perception between two techniques after the first injection. VA technique was found to be clinically more successful when compared with CIANB. Regarding some pain perception after the first injection, patients perceived 20% less pain clinically with VA technique when compared with CIANB. For no pain after the second injection, VA technique proved to be 10% more successful than CIANB. For the parameter some pain after the second injection, none of the patients experienced pain in VA technique, while 5% of patients experienced pain in CIANB. Overall, the quality of anesthesia achieved with VA technique was more clinically successful though it was not statistically significant. Our result was almost similar to the study carried out by Allen L. Sisk, where both CIANB and VA technique showed no statistical difference in the quality of anesthesia [4]. Many studies also concluded that the effectiveness of anesthesia was found to be better in direct conventional technique during the operative discomfort or pain experienced by the patient [4, 14, 23]. The reason for this can be assumed due to everyday practice by Todorovic et al. [21]. The tissues in the retromolar area of the maxilla are relaxed when the mouth is in the semi-open or closed position, and the penetration of the needle is, therefore, relatively painless [5]. A study also showed higher incidence in the depth and frequency of anesthesia during dental extraction procedure by Gow-Gates technique (92.5%) followed by VA technique (90%) and CIANB (72.5%).3 Todorovic et al. also recorded the depth of anesthesia according to discomfort experienced during tooth extraction, and it showed a significantly lower number of painless extraction after the tuberosity approach, i.e., Akinosi technique in comparison with the CIANB and Gow-gates technique [21]. Another study also found that the depth of anesthesia achieved between inferior alveolar nerve block and VA did not differ significantly [6, 23].

Intravascular injection of local anesthetic during nerve block injection is common [27]. In order to eliminate vascular accidents, the importance of performing an aspiration before deposition of local anesthetic solution is well known because injection of local anesthetic agent with vasoconstrictor may result in cardiovascular and central nervous system toxicity, as well as tachycardia and hypertension [21, 27]. The low rate of positive aspiration with VA technique suggests the absence of sizable blood vessels in the target area. The aspiration rate of 22% observed during the CIANB is higher than all the reported ones [22, 28]. However, according to our current study both the injection technique showed no positive aspiration. It seems the side of the injection has no considerable effect in the incidence of intravascular needle entrance. The reason can also be due to less sample size. Also, it seems that the rate of intravascular needle entrance might be higher among general dental practitioners. But positive aspiration was not observed in either of the two injection techniques in our study.

Studies also reported cases of syncope, feeling of shock and pallor[29–31]. Barlett also founded the greatest number of reactions (vomiting, nausea and loss of consciousness, diplopia and tremor) due to inadvertent intravascular injections during mandibular nerve block [32]. But none of these reactions are encountered in our present study.

In our study, four cases (20%) in classical inferior alveolar nerve and one case (5%) in VA technique required need for re-injection. So clinically, CIANB showed more re-injection needed compared with VA technique. This favored the study performed by Hassan Mohajerani et al., where more re-injection is needed for convention technique [6]. However, in a study by Nitin Verma and Jeevan Lata, the frequency of supplementary injection was found to be higher in Vazirani–Akinosi technique than the conventional technique which was similar to the studies of Donker et al. and Yucel and Hutchinson [11, 14, 22]. The reason may be due to the lack of sufficient bony landmarks and failure to appreciate the flaring nature of the ramus, causing deposition of the local anesthetic solution outside the confines of the pterygomandibular space [14].

In a study, the incidence of inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve anesthesia with single nerve block was found to be lower in Vazirani–Akinosi technique [14]. For buccal nerve, they used separate needle puncture for anesthetizing buccal nerve in conventional technique and hence so conclude that valid reason cannot be made. But in our study, the incidence of inferior alveolar nerve anesthetized with single nerve block observed was 90%, 90% for lingual nerve anesthesia was achieved with single injection and 100% for buccal nerve anesthesia was achieved with buccal nerve infiltration, whereas in VA technique, 100% for inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia, 100% for lingual nerve anesthesia and 95% for buccal nerve anesthesia were achieved with single injection. Therefore, no statistical difference was noted in all the three injection techniques regarding nerve anesthetized with single injection. In a study by Donker et al., 8% of the patient in the conventional injection group reported an “electric shock” sensation in the lower lip during the injection and one patient with numbness of the ear [22]. In VA technique, 11% of the patient showed tingling of the upper lip, infra-orbital nerve anesthesia, posterior superior alveolar nerve anesthesia, blanching of skin of infra-orbital region and palpitation. However, in our present study complications like sloughing, soft tissue injury, anesthesia or paraesthesia, needle breakage, hematoma, VII nerve palsy and syncope were not encountered. Also, no cases of infection were reported probably due to the usage of disposable needles, syringes, aseptic techniques and sterile solutions throughout the study.

In the present study, with regard to all the parameters, both the two injection techniques showed a high rate of success in achieving mandibular anesthesia showing no statistical difference in their effect except for VA technique showing statistically significant results in terms of pain. In addition to, VA technique was more clinically superior over the CIANB in terms of duration of anesthesia, quality of anesthesia and the need for re-injection.

Funding

This study was not funded by any individuals or private or government institution.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (name of committee–institutional ethics committee, reference number-IEC 05/2016) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Preethi Bhat, Email: preeti_bht@yahoo.com.

Hijam Thoithoibi Chanu, Email: hijamthoi9@gmail.com.

Sathish Radhakrishna, Email: drsathish75@gmail.com.

K. R. Ashok Kumar, Email: drashok.kumar26@gmail.com

T. R. Marimallappa, Email: drmarimallappa@gmail.com

R. Ravikumar, Email: drravi78in@gmail.com

References

- 1.Madan N, et al. A randomized controlled study comparing efficacy of classical and Gow-Gates technique for providing anesthesia during surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molar: a split mouth design. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;16(2):186–191. doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0960-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamalpour MR, Talimkhani I. Efficacy of the Gow-Gates and inferior alveolar nerve block techniques in providing anesthesia during surgical removal of impacted lower third molar: a controlled randomized clinical trial. Avicenna J Dent Res. 2013;5(1):26–29. doi: 10.17795/ajdr-20938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sthitaprajna L, Nikil J, Mohanty J, Dhirendra KS, Gulati M. A clinical comparison of three techniques of mandibular local anaesthesia. J Res Adv Dent. 2013;2(3):61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisk AI. Evaluation of the Akinosi mandibular block technique in oral surgery. J Oral Maxlllofac Surg. 1966;44(2):113–115. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(86)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akinosi JO. A new approach to the mandibular nerve block. Br J Oral Surg. 1977;15(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(77)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohajerani H, Pakravan AH, Bamdadian T, Bidari P. Anesthetic efficacy of inferior alveolar nerve block: conventional versus Akinosi technique. J Dent Sch. 2014;32(4):210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra S, Tripathy R, Sabhlok S, Pankaj Kumar P, Satyabrata P. Comparative analysis between direct conventional mandibular nerve block technique. IJART. 2012;1(6):112–117. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heard AMB, Green RJ, Lacquiere DA, Sillifant P. The use of mandibular nerve block to predict safe anaesthetic induction in patients with acute trismus. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(11):1196–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggarwal V, Mamta S, Kabi D. Comparative evaluation of anesthetic efficacy of Gow-Gates mandibular conduction anesthesia, Vazirani–Akinosi technique, buccal-plus-lingual infiltrations, and conventional inferior alveolar nerve anesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(2):303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donkor P, Wong J. A mandibular block technique useful in ‘gaggers’. Aust Dent J. 1991;36(1):47–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1991.tb00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yucel E, Hutchison IL. A comparative evaluation of the conventional and closed-mouth technique for inferior alveolar nerve block. Aust Dent J. 1995;40(1):15–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1995.tb05606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg S, Reader A, Drum M, Nusstein J, Beck M. Comparison of the anesthetic efficacy of the conventional inferior alveolar, Gow-Gates, and Vazirani–Akinosi techniques. J Endod. 2008;34(11):1306–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pratibha S, Jadhav GR, Priya M, Surapaneni S, Kalra D, Sakri M, Basavaprabhu A. Comparative evaluation of effect of preoperative alprazolam and diclofenac potassium on the success of inferior alveolar, Vazirani–Akinosi, and Gow-Gates techniques for teeth with irreversible pulpitis: randomized controlled trial. J Conserv Dent. 2016;19(5):390–395. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.190013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nitin V, Jeevan L. Comparison and clinical efficacy of mandibular nerve aesthesia by direct conventional technique with Vazirani–Akinosi mandibular nerve block technique. J Anaesth Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26(1):79–82. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.75122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahima G, Ravi N, Poonampreet B. Efficacy of anesthesia of long buccal nerve in Akinosi closed mouth technique—a prospective study. IJDS. 2013;5(2):13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lew K, Townsend G. Failure to obtain adequate anaesthesia associated with bifid mandibular canal: a case report. Aust Dent J. 2006;51(1):86–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma R, Jayakumar T, Lekha S, Srirekha A, Srinivas R, Swetha RS, Odedra K. A comparative evaluation of the efficacy of different mandibular anesthetic technique in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2018;30(1):45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruz EV, Quengua JB, Gutierrez IL, Abreu MA, Uy HG. A comparative study: classical, Akinosi and Gow-Gates technique of mandibular nerve block. J Philipp Dent Assoc. 1994;46(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Click V, Drum M, Reader AI, Nusstein J, Beck M. Evaluation of the Gow-Gates and Vazirani–Akinosi techniques in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: a prospective randomized study. J Endod. 2015;14(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa FA, Souza LMA, Groppo F. Comparison of pain intensity during inferior alveolar nerve block. Rev Dor Sao Paulo. 2013;14(3):165–168. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donkor P, Wong J, Moorthy AP. An evaluation of the closed mouth mandibular block technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19(4):216–219. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez GJM, Benito Pena B, Fernandez Caliz F, San Hipolito L, Penarrocha DM. A comparative study of direct mandibular nerve block and the Akinosi technique. Med Oral. 2003;8(2):143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarat RKB, Kashyap VM, Uday Kiran U, Tiwari P, Mishra A, Akansha S. Comparison of efficacy of Halstead, Vazirani–Akinosi and Gow-Gates techniques for mandibular anesthesia. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2018;17(4):570–575. doi: 10.1007/s12663-018-1092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montserrat-Bosch M, et al. Efficacy and complications associated with a modified inferior alveolar nerve block technique. A randomized, triple-blind clinical trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19(4):391–397. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Todorovic L, Stajcic Z, Petrovic V. Mandibular versus inferior dental anaesthesia: clinical assessment of 3 different techniques. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15(6):733–738. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(86)80115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravinder S, Nageshwar D, Amit B, Mahesh G, Gyanander A, Davender K. Comparative evaluation and clinical assessment of Gow-Gates, Vazirani–Akinosi and conventional inferior alveolar nerve block techniques. JIDA. 2013;7(4):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohan M, Tarun J, Rajendra P, Sharma SM, Gopinathan T. Positive aspiration and its significance during inferior alveolar nerve block—a prospective study. Nitte Univ J Health Sci. 2014;4(3):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taghavi Zenouz A, Ebrahimi H, Mahdipour M, Pourshahidi S, Amini P, Vatankhah M. The incidence of intravascular needle entrance during inferior alveolar nerve block injection. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2008;2(1):38–41. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2008.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cvetko E. Bilateral anomalous high position of the mandibular foramen: a case report. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36(6):613–616. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pogrel MA, Bryan J, Regezi J. Nerve damage associated with inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126(8):1150–1155. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pei-Chuan H, Hao-Hueng C, Puo-Jen Y, Ying-Shiung K, Wan-Hon L, Chun-Pin L. Comparison of the Gow-Gates mandibular block and inferior alveolar nerve block using a standardized protocol. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105(2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasconcelos BC, Freitas KC, Canuto MR. Frequency of positive aspirations in anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve by the direct technique. Med Oral Patol Oral Cirbuccal. 2008;13(6):371–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]