Abstract

In previous word reading studies, lexicality has been used as a variable to examine the impacts of word form and meaning information on the many stages of word recognition process. Yet the neural dynamics associated with lexicality effect of various information processing for Chinese visual word recognition has not been well elucidated. In this study, Chinese native speakers were instructed to read Chinese disyllabic compound words, morphological legal (pseudo-words) and illegal non-words with their brain potentials recorded. Event-related potentials (ERP) results showed that N200 was related to Chinese orthographic processing, where three lexical conditions elicited comparable patterns. A semantic discrimination was found for N400 between pseudo-words/non-words and real words, which is in favor of the lexical view of the N400 effect. Further, a later ERP component P600 exhibited the difference between the non-words and pseudo-words, reflecting a re-analysis of word meaning or grammatical operation on Chinese morphological legality. Therefore, we argue that Chinese morphological information might have an independent representation (the P600 effect) in mental lexicon.

Keywords: Chinese compound word, Lexicality effect, Morphological processing, ERP

Introduction

Visual word recognition among normal native speakers with different linguistic backgrounds is believed to be a multi-stage process, involving an anatomically distributed neural system (Mechelli et al. 2003; Liu et al. 2003; Davis 2004; Zhang et al. 2009, 2020; Carreiras et al. 2014). This process implicates several cognitive sub-processes, from the visual pattern identification and/or phonological mediation (Coltheart et al. 2001; Fiebach et al. 2002) which consist of the word form, to the retrieval of lexico-semantic and morpho-syntactic information from the word form (Booth et al. 2006; Hauk et al. 2006; Wang 2011; Lo et al. 2019; Prins et al. 2019). Previous studies have been performed to inspect the temporal characteristics of lexical information during visual word recognition, which includes word length (Juphard et al. 2006), morpheme property (Gao et al. 2021), word and morpheme frequency (Rugg 1990; Zhang and Peng 1992; Zhang et al. 2009), word category (Liu et al. 2007; Xia et al. 2016), and semantic transparency (Libben 1998; Libben et al. 2003; Lu et al. 2012). By manipulating or combining different lexical factors, these studies shed light upon various perspectives of the nature of multi-stage processing potentially involved in visual word recognition.

Particularly, various paradigms associated with lexicality (also termed lexical status, or word/non-word/pseudo-word difference) have been employed to examine the time courses of orthographic, phonological, and semantic activations in alphabetic writing system (e.g., Bentin et al. 1999; Hauk et al. 2006). In these paradigms, non-word denotes a letter string which violates the regularities at different levels (i.e., orthographic/phonological/semantic level, constitute/word level). Of various non-words, pseudo-word is a word-like form without semantic representation in native speakers’ mental lexicon, which are not real words yet pronounceable on the basis of orthographic and phonotactic rules (Mechelli et al. 2003). By contrast, illegal non-word, or false word (hereafter “non-word”) is a letter sequence that does not satisfy any English orthographic rule. Importantly, non-words and pseudo-words lack any established meaning and have low frequency (zero) for language users. Therefore, lexicality could be used as a variable to examine the impacts of word form and meaning constraints on the many stages of the recognition process (Bentin et al. 1999; Hauk et al. 2006).

To date, a number of electroencephalography (EEG) studies have been performed to explore the brain activation difference between words and non-words during meaning retrieval and integration. Significantly higher amplitude of N400 was elicited from non-words as compared to that for words in English studies (Holcomb and Anderson 1993; Rugg et al. 1995; Otten et al. 2007). The N400 response, a negativity starting from 200 to 300 ms and peaking around 400 ms over centro-parietal sites, has been recognized as the canonical semantic incongruity indicator in sentence reading (Kutas and Hillyard 1980). As a consequence of differing lexical conditions (e.g., semantic typical/anomaly), the N400 effect was linked to a “lower-level” process of accessing word meaning, and/or a top-down semantic integration mechanism (e.g., Bentin et al. 1985; Rugg 1985; Deacon et al. 2004; Hauk et al. 2006; Lau et al. 2008). What is not yet clear is whether the N400 lexicality effect would implicate a lexical integration or lexical access process, which warrants discussions from different languages and paradigms.

In addition to the lexico-semantic N400, accumulating evidence also demonstrated significant ERP lexicality effect in pre-lexical processing of orthographic and/or phonological information (Rugg and Barrett 1987; Bourassa and Besner 1998; Doyle et al. 1996; Deacon et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2020). For example, Hauk et al. (2006) found that English words and pseudo-words exhibited notable differences in the latency of ERP waves. The distinction firstly appeared at 160 ms after word onset which reflects the early visual analysis of the word form, and subsequently pronounced at the later stage (> 200 ms), indicating the retrieval of lexico-semantic information.

Unlike alphabetic languages, however, the criterion for differentiating between pseudo-words and non-words and detecting lexicality effect has not been well established for the Chinese writing system. Written Chinese is often described as morphosyllabic (DeFrancis 1989), in which each character represents a single-syllable morpheme for the most cases. More than 70% of Chinese vocabulary is formed by compounding instead of inflection (e.g., work-working) or derivation (e.g., joy-joyful) in alphabetic languages like English. Therefore, the paradigms and findings from previous English studies might not be directly applied to Chinese word cases. Taking Chinese orthography as an example, it denotes two kinds of information, including character-level and word-level orthography. Character-level orthography indicates the regularity and consistency of individual characters (e.g., Hong et al. 2016; Yum and Law 2019). Meanwhile, word-level orthography involves the spelling regularities of both constitute characters and whole words, thus implicating more extensive and higher-level visual identifications. Although a variety of investigations have been carried out into the orthographic and semantic activation associated with Chinese character recognition (e.g., Liu et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2006a, b; Chen et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2009), only a few studies were conducted at the Chinese word level.

Among single-character studies, Zhang et al. (2009) inspected the time courses of phonological and semantic activation associated with Chinese single-character word recognition by using the semantic/homophone judgment task. As a result, P200 response was identified for homophonic pairs, indicating that a phonological activation was detected earlier than the semantics, which was associated with a frequency-mediated N400 effect. A similar neural pattern was obtained from a recent study (Wu et al. 2020) by using homographic morphemes in Chinese homographs with a masked priming paradigm. However, since no alternative Chinese word types were involved in the abovementioned studies, no quantified ERP components were linked to word-level orthographic information.

Importantly, Zhang et al. (2012) reported a widespread N200 response over bilateral centro-parietal regions of the human brain in recognizing Chinese disyllabic words, yet not in reading Chinese single-character words (e.g., Zhang et al. 2009; Hsu et al. 2009) and alphabetic words (Zhang et al. 2012). First, even though single high- and low-frequency real words and pseudowords generated stable N200 activities, there was no significant difference across the three lexical conditions. Null N200 lexicality effect was therefore interpreted as an orthographic processing indicator of individual Chinese disyllabic words reading. Since there is no visual difference and orthographic constraint between real words and pseudo-words at the whole-word level, N200 is unaffected by word frequency or lexicality. By contrast, N200 is found sensitive to repetition priming in Chinese visual word recognition, because the visual analysis has been enhanced at the second occurrence. Both real word and pseudo-word repetition elicited enhanced N200 effect (Du et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2016), while there was no statistical difference between real words and pseudo-words (Zhang et al. 2012: Experiments 3 and 5). Meanwhile, N200 was dissociated from the processing of non-linguistic characteristics of disyllabic words, as 2-character Korean words (completely unfamiliar to participants) failed to generate comparable N200 patterns (Zhang et al. 2012: Experiment 2). Those findings were taken together to suggest that centro-parietal N200 is specific to the orthographic analysis of Chinese disyllabic compound word recognition, rather than non-linguistic visual analysis (Zhang et al. 2012), which is also independent of semantic processing (Du et al. 2014). Nevertheless, while repetition N200 enhancement has been well studied, the null effect of N200 lexicality requires further examinations when N200 is considered as the orthographic marker of Chinese disyllable word recognition.

In addition, the morphological information of Chinese compound words is also vital to Chinese vocabulary in terms of decoding the temporal dynamics of Chinese lexicality effect. Recently, Gu and Yang (2010) demonstrated that the function of P600 (prominent in midline) in reading Chinese compound words was correlated with high or low morphological productivity. Higher amplitudes of P600 were detected from higher morphological productivity. However, they didn’t inspect the lexicality effect by measuring the difference between word and pseudo-word, nor did they access the lexical property of pseudo-words. For example, it is unclear to what extent pseudo-words resemble or differ from real words regarding the neural patterns. Moreover, Du et al. (2013) illustrated that Chinese morphological processing was associated with a fronto-central N200 and then a later-stage N400 (more pronounced in midline and left hemisphere), while no morphology-related P600 effect morphology was detected. The P600 activity was associated with the sensitivity to syntactic violations and structural/combinatorial constraints in classic language ERP studies (Hagoort et al. 1993; Kuperberg 2007). Extending the scope to module-general domain, recent modelling work suggested that P600 might reveal an error-based language learning mechanism adapting to contextual language inputs (Fitz and Chang 2019), or a domain-general brain response to novelty as a later counterpart of P3 (Sassenhagen and Fiebach 2019). However, the presence of the morphological P600 in Chinese compound reading and the functional interpretation of this response is still inclusive.

More importantly, classic theories on mental lexicon (e.g., Levelt 1989) suggested that morphological and syntactic information of a lexical entry is also activated besides the semantic activation during lexical access and processing. Nevertheless, no studies have been performed to examine how to take Chinese morphological information into account when addressing lexicality effect. Meanwhile, Chinese word form representation and semantic activation by other types of non-words have never been touched upon.

Therefore, this pilot study aims to examine the dynamic unfolding and neural underpinnings of lexicality effect in reading Chinese compound words presented in isolations by using ERP technique. It is hypothesized that early orthographic, semantic, and late morphological ERP markers could be manifested during this process. To test this hypothesis, well-controlled words, pseudo-words, and non-words were used to evoke the ERP correlates of orthographic, semantic, and morphological representations, thus suggesting a multi-stage feature of dynamic Chinese compound word processing. In particular, we will inspect whether N200, N400, and P600 are the essential neural indexes of the early and late Chinese lexical processing, which are the key components of word recognition. It is anticipated that the investigation into real words and different non-words will help establish a new method for improving the understanding into the neural mechanism of Chinese word reading.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-two Chinese college students (14 females, mean age: 23.5 years) were recruited from Beijing Language and Culture University campus. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision with right handedness, which was assessed by Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield 1971). All participants reported no histories of neurological or psychiatric disorders. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study was conducted with the ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of both the University of Macau and Beijing Language and Culture University.

Materials

Three groups of high-frequency disyllabic Chinese compound words were excerpted from CNCORPUS database (www.cncorpus.org/), which were matched on word frequency (the mean of each group > 24 per million). Each of the three groups consisted of 54 Chinese words. The real words were from the first group, which were kept unchanged. However, this was not the case for group two, in which the pseudo-words were created by substituting a synonym or a semantically related morpheme for a character morpheme of the compound word. For example, “发笑” (pronunciation: fa1 xiao4; literal meaning: burst out + laughing; word meaning: laugh) was a real word initially from group two and then “发哭” (pronunciation: fa1 ku1; literal meaning: burst out + crying; there is no such a word in native speakers’ lexicon though) was coined as a corresponding morphologically legal pseudo-word. In addition, non-words were produced by concatenating any two characters, each of which was a real character from group three and also high-frequency token from the dataset. As a result, combination of these two characters yielded a pronounceable meaningless string (Leong et al. 2005), such as “吃远” (pronunciation: chi1 yuan3; literal meaning: eat + far).

In addition, real words and pseudo-words were matched in terms of part of speech and morphological structure. Pseudo-words and non-words were not homophonic to any real words to avoid possible phonological activation in word recognition. To confirm the validity of pseudo-words, two Chinese linguistics professors from the University of Macau were invited to inspect whether the character strings of pseudo-words and non-words satisfied one of the morphological structures of Chinese compound words. Over 80% of their ratings remained consistent (see the details of morphological structures from Table 1). Real words, pseudo-words, and non-words were matched regarding stroke numbers [F(2,161) = 0.893. p = 0.412] and character frequency [F(2,232) = 0.06, p = 0.941]. Besides, additional 54 real words were used as fillers to balance the frequency of “Yes” and “No” responses in the lexical decision task. They were compound words randomly extracted from CNCORPUS.

Table 1.

Examples and lexical characteristics across experimental conditions

| Real word | Pseudo-word | Non-word | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Examples | Word forms | 快乐/kuai4 le4/ | 发哭/fa1 ku1/ | 吃远/chi1 yuan3/ |

| Meaning | happy | burst out + crying | eat + far | |

| Word frequency | (per million) | 31.9 | N/A | N/A |

| Character frequency | (per million) | 313 | 323 | 307 |

| Number of strokes | 13.7 | 14.2 | 13.3 | |

| Part of speech | Noun | 29 | 27 | N/A |

| Verb | 19 | 20 | ||

| Adjective | 4 | 5 | ||

| Adverb | 1 | 1 | ||

| Others | 1 | 1 | ||

| Morphological structures | Coordination | 18 | 10 | N/A |

| Modification | 28 | 28 | ||

| Subject-Verb | 1 | 1 | ||

| Verb-Object | 2 | 11 | ||

| Complement | 5 | 4 |

Visual lexical decision task

The stimuli consisted of 54 real words, 54 pseudo-words, 54 non-words, and 54 fillers in total. The schematic of the paradigm utilized for the present study was displayed in Fig. 1. All stimuli were divided into three equal blocks and each individual block had 72 trials, which were presented randomly (Yes/No buttons were counterbalanced among all participants) and coded by using E-prime 2.0 program (Psychology Software Tool, Inc.). All Chinese characters were presented in the style of Chinese Song font with 16 by 16 mm against black background.

Fig. 1.

Schematic demonstration of the experimental procedure. Participants read four types of materials (real words, pseudo-words, non-words, and fillers) and judged whether they were real word or not by pressing “Yes” or “No” buttons when they saw two question marks in the screen

Each trial started with a fixation cross (800–1000 ms) at the center of PC monitor, followed by a blank screen (250 ms), and then the target word (400 ms). After the target word disappeared, the probe with two question marks would show up. Participants were instructed to determine whether the previously displayed character string was a legitimate word or not by pressing the Yes or No button labeled in the keyboard as quickly as possible. If they failed to respond at the probe within 3 s, this trial would be marked as a wrong response. Once a response was made, there would be a blank lasting for 1000 ms until the next trail. Yes/No buttons were counterbalanced across all participants.

Prior to the EEG recordings, participants were required to perform a practice session which contained 7 real-word and 7 non-word trials. Correct or incorrect feedbacks were provided once they made a response. Only the participants with an accuracy of over 80% during the practice were allowed to proceed to the formal experiment. During the test, participants were seated in front of a monitor at a distance of 60–70 cm in a sound-attenuated lab. They were asked to minimize body movements and eye blinks to reduce the possible artifacts on EEG signals.

EEG data acquisition and analysis

EEG data were recorded from the scalp through 64 non-polarizable Ag/AgCl sintered electrodes attached to an elastic cap with the international 10–20 system (Neuroscan Inc., Compumedics, Australia). In addition, vertical and horizontal electrooculogram (EOG) signals were collected with electrodes placed above and below the left eye, and on the outer canthi of both eyes, respectively. Data were digitalized at a sampling rate of 500 Hz and filtered with a band-pass of 0.05–100 Hz. Electrode impedances were maintained below 5 kΩ. During the recordings, the left mastoid (M1) was used as the online reference.

For offline EEG signal processing, EEG data were first filtered by using Curry 8 software with a band-pass filter of 0.05–30 Hz (12 dB) and re-referenced to the average of left and right mastoids (M1, M2). Channels affected by eye-movement artifacts were corrected by using an ocular artifact reduction model from Curry 8. Incorrect responses and trials with artifacts larger than ± 100 μV were discarded for further analysis. A minimum of 40 artifact-free trials were retained for each of the three lexical conditions from each participant. Epochs locked to word stimulus from − 100 to 800 ms were generated, involving 100 ms pre-stimuli period as baseline and 800 ms post-stimuli period. And then grand-averaged waveforms of all conditions were calculated for each individual channel from each participant.

Three dominant ERP components were identified based on the visual inspection and previous studies (i.e., N200, N400, and P600). They were then analyzed in the time windows of 190–235 ms (N200), 300–500 ms (N400), and 500–700 ms (P600). In particular, N200 was detected from the amplitudes of frontal (F1, Fz, F2), fronto-central (FC1, FCz, FC2), and central electrodes (C1, Cz, C2), while N400 and P600 were determined from the electrodes in fronto-central (FC1, FCz, FC2), central (C1, Cz, C2), and centro-parietal (CP1, CPz, CP2) regions (Du et al. 2013).

Results

Behavioral data

One participant’s behavioral data was not recorded due to the experimenter’s mal-operation with E-prime. Mean reaction time (RT) for correct responses and accuracy rate (ACC) were calculated across three lexicality conditions for each participant (Table 2). Responses that were either incorrect or exceeded two standard deviations (SD) from each participant’s mean RT were removed, which took up less than 5% of the total trails.

Table 2.

RT and ACC of three lexicality conditions

| Real word | Pseudo-word | Non-word | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| RT (ms) | 658.8 | 104.5 | 768.3 | 132 | 711.5 | 115 |

| ACC (%) | 98.4 | 0.6 | 90.3 | 1.2 | 98.8 | 0.4 |

Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare the differences in averaged RT and ACC across three conditions. Results showed a significant main effect of lexicality on RT, F(2,40) = 35.0, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.636. Three paired-samples t tests demonstrated that real words were recognized faster than pseudo-words and non-words, while the pseudo-word case exhibited the longest RT (ps < 0.001). Meanwhile, the ACC data also illustrated a lexicality main effect, F(2,40) = 28.7, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.589. The ACC of pseudo-words was significantly lower than those of real words and non-words (ps < 0.001), whereas the real word and non-word cases showed no significant difference (p = 0.65).

ERP data

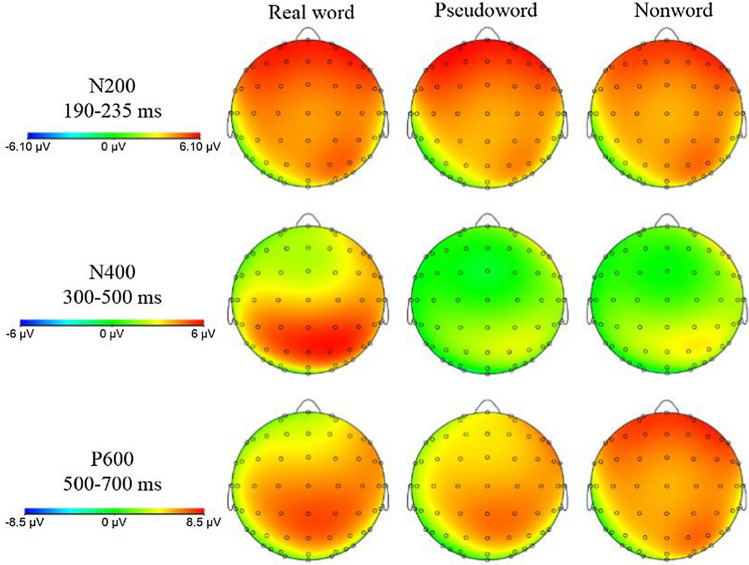

The grand-averaged ERP waveforms of associated electrode sites were plotted in Fig. 2 for three lexicality conditions, whereas the scalp topography map associated with N200, N400 and P600 was respectively displayed in Fig. 3. N200, N400, and P600 effects were examined as follows.

Fig. 2.

Grand-averaged ERP waveforms across three lexicality conditions in selected electrodes. The black curve represents the real word condition, the blue curve denotes the pseudo-word condition, and the red curve represents the non-word condition. N200, N400, and P600 were marked on representative electrodes, respectively. (Color figure online)

Fig. 3.

Grand-averaged ERP topographies of N200, N400, and P600 across three lexicality conditions, respectively. Topological plots showed the lexicality N200 effect in fronto-central and central regions, N400 effect in central region, and P600 effect in centro-parietal region

N200 A three-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction (Greenhouse and Geisser 1959) was performed on N200, with lexicality, laterality (midline, left/right hemisphere), and electrode position (frontal, fronto-central, central) as independent factors. The main effect of electrode position was identified, F(2,42) = 5.66, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.212. A further pairwise comparison revealed that negativities were significantly increased from frontal to fronto-central and central positions (− 5.4 vs. − 4.8 vs. − 4.3 μV, ps < 0.05), while the fronto-central and central regions exhibited no significant difference on N200 amplitude (p = 0.103). Main effects and interactions with other factors were not reliable.

N400 In terms of the measure of N400, the main effects were significant for the lexicality [F(2,42) = 22.7, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.519], laterality [F(2,42) = 3.4, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.138], and electrode positions [F(2,42) = 18.0, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.46]. The results of follow-up comparisons were as follows: (1) pseudo-words and non-words elicited higher amplitude of N400 than real words (0.8 vs. 1.1 vs. 3.7 μV, ps < 0.01); (2) N400 amplitudes significantly increased from the right hemisphere to midline (2.2 vs. 1.6 μV, p < 0.05); (3) the electrodes in fronto-central and central regions exhibited larger N400 peaks than those in centro-parietal area (0.8 vs. 1.6 vs. 3.2 μV, ps < 0.05).

The interaction between the laterality and position was also reliable, F(4,84) = 4.26, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.169. Further comparisons revealed that the amplitudes of N400 at FCz and Cz were significantly larger than those at FC2 and C2 (ps < 0.05).

P600 The repeated-measures ANOVA was performed for P600, where a reliable main effect of lexicality was identified, F(2,42) = 4.3, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.17. In addition, a comparison between the three conditions was conducted, and it was discovered that the non-word condition elicited a larger P600 amplitude than the pseudo-word case (7.2 vs. 5.6 μV, p < 0.05). Interestingly, the main effects of the laterality [F(2,42) = 3.8, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.153] and position [F(2,42) = 13.2, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.39] were also identified. Further pairwise comparisons revealed that electrodes on the right hemisphere elicited significantly larger P600 amplitudes than those from the midline and left hemisphere (6.5 vs. 6.3 vs. 6.0 μV, ps < 0.05). In particular, the P600 effect was more significant in the centro-parietal and central regions than that from the fronto-central cortex (7.1 vs. 6.3 vs. 5.4 μV, ps < 0.05).

More importantly, we discovered that the interaction between the lexicality and position was also significant, F(4,84) = 3.7, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.15. Follow-up analyses demonstrated that the P600 amplitude was higher for the non-word condition as compared to that of the pseudo-word condition over all positions (ps < 0.05). Further analysis also indicated that the non-word condition elicited a statistically larger P600 amplitude in the fronto-central region than the real words (7 vs. 5 μV, p < 0.05).

Meanwhile, the interaction between the laterality and position was also significant, F(4,84) = 4.26, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.17. Further analyses showed that the P600 amplitude was significantly more positive at FC2 than that at FCz and FC1 (7 vs. 6.1 vs. 5.2 μV, ps < 0.05). In addition, P600 amplitude at CPz was larger than that at CP1 (6.5 vs. 5.7 μV, p < 0.001). No additional interactions were identified.

Discussion

Behavioral data

In this study, behavioral data showed that both non-words and pseudo-words generated longer RT and lower ACC than real Chinese compound words. The current results were consistent with the previous evidence (Lu et al. 2012) that both transparent and opaque real words were detected faster than derived pseudo-words and non-derived non-words. Since the largest difference between the real words and non-words is whether there is a ready-made linguistic representation in mental lexicon, it should be much easier for native Chinese speakers to accept an existing word than reject a novel character string. Unlike the previous studies (Lu et al. 2012), however, the difference in RT between the pseudo-words and non-words was also clearly unveiled from the present work, which might be due to the signature of morphological legality, illustrating the validity of pseudo-words and non-words. Nevertheless, the behavioral performance can only provide indirect evidence of lexicality effect, which failed to address the relative time courses of orthographic, semantic, and morphological information involved in the process of Chinese word recognition.

N200 results

Of high temporal resolution, ERP technology is able to capture more complex and fine-grained temporal dynamics of Chinese word recognition at different stages. In particular, a negative deflection peaking around 200 ms after word onset was detected. It showed up relatively earlier at bilateral central scalp sites, whose distribution was in line with the N200 response documented in previous work (Zhang et al. 2012). Both the current finding and the previous results (Zhang et al. 2012; Du et al. 2013) manifested a null N200 lexicality effect between Chinese real words and pseudowords. As both pseudowords and real words are made of two individual characters which are orthographically legal, there is no reliable visual difference between the two conditions at the early identification. Importantly, the current N200 results extended the previous findings by showing that N200 effect is persistent regardless of the morphological legality during the orthographic analysis. This consistency on N200 enhanced the hypothesis that bilateral centro-parietal N200 could work as the biomarker of visual analysis for the orthographic identification of individual Chinese disyllabic words.

The null N200 lexicality effect also excludes the possibility that the RT difference across three conditions results from the orthographic inconsistency. Instead, this difference might be mostly associated with later processing after 250 ms, as indexed by the ERP components N400 and P600.

N400 effects

Note that neither N400 nor P600 effects identified in the current study could directly relate to response-related motor intention, as their distributions were distinct from that of Lateralized Readiness Potentials (LRP, Kutas, and Donchin 1980; Rinkenauer et al. 2004). Given the null N200 lexicality effect, longer reaction times associated with non-words and pseudo-words might be caused by the functional distinction in the time window of N400 effects. In the current study, non-words and pseudo-words exhibited higher N400 amplitude in the central brain region than the real words, showing a good agreement with previous findings in English (e.g., McKinnon et al. 2003; Hauk et al. 2006) and in Chinese (Zhang et al. 2009; Du et al. 2013). Nevertheless, to date there is not yet a consensus regarding the functional interpretation of the N400 effect in lexical semantics (see Lau et al. 2008, for review). The integration account believed that the N400 effect might reflect a post-access mechanism of fitting the critical word meaning into the sentential context. For instance, the amplitude of N400 was found more negative when reading the semantically incongruent endings in the sentence “I like my coffee with cream and socks”, than the response to the semantically typical ending (i.e., sugar). Drawing on the perspective of semantic integration and top-down processing mechanism, more cognitive efforts were employed to process the implausible flow so as to integrate the anomaly into the working context. Alternatively, the N400 component was postulated to index word meaning retrieval from lexical-semantic memory by the lexical access view (Brouwer et al. 2017). In the abovementioned sentence, proceeding context would pre-activate several supportive lexical candidates (e.g., sugar, milk), which were stored in the longer-term memory in the mental lexicon. The predictable word (i.e., sugar) would make the lexical access easier than the anomalous ending (socks) when mapping the critical word to the results of lexical search.

As this present work was carried out using single words rather than prime-target word pairs or words in sentential contexts, the results were taken as more supportive of the lexical access view. Higher N400 amplitudes elicited by non-word and pseudo-word might involve a process of lexical competition and inhibition, which is much more effortful than well-established real words. To identify a non-word or pseudo-word, participants need to inhibit the activated lexical counterparts and candidates. More importantly, no difference in N400 between non-words and pseudo-words was detected, which is inconsistent with previous studies (Lu et al. 2012). This difference can be explained by differing operationalization of pseudo-words and non-words, which has been discussed in our behavioral data analysis. Yet this null effect enhanced the hypothesis of an automatic bottom-up mechanism, because relative to real words, both non-words and pseudo-words lack any ready-made lexical representations in semantic memory. As no sentential context was involved in the lexical decision task, the integration view does not apply to the current case.

P600 effects

In addition to N400, pseudo-words elicited a lower positive deflection than non-words at the central and centro-parietal sites along the right hemisphere in the current study, which is in line with the P600 syntactic/grammatical processing effect. P600 is attributed to the neural sensitivity and extra cognitive efforts resulting from syntactic violations in sentence reading (Osterhout and Holcomb 1992; Kim and Osterhout 2005) and a domain-general structural analysis processing (Kuperberg 2017; Kuperberg et al. 2020). In terms of Chinese reading studies, Gu and Yang (2010) first reported the P600 effect, indicating that it is associated with Chinese morphological processing of disyllabic compound words of higher versus lower morphological productivity. The present findings further illustrated that P600 can be elicited by manipulating the legality of morphological structure. As the contrast between pseudo-words and non-words denotes a word structure sensitivity, the P600 detected in this study might reflect a process during which the constitute characters are combined to retrieve word meaning based on Chinese morphological rules. Although pseudo-words showed a comparable N400 pattern with non-words at an earlier stage, semantic analysis and discrimination between the two were not resolved. Instead, the brain tended to the morpho-syntactic system and mapped the stimulus onto an existing morphological representation at a later stage, which implicated a controlled and strategic mechanism. Combined, these results indicate that the P600 might be linked to structural/combinatorial process when decoding morphological legality.

Meanwhile, even the “Yes” and “No” responses to target words were balanced in the current design, the percentage of legal morphology (i.e., experimental real words, real words as fillers, and pseudowords) was actually three times of illegal morphology (i.e., illegal nonwords). The biased distribution could involve a task-relevant morphological prediction. A recent modelling work (Fitz and Chang 2019) suggested that language ERPs could be viewed as the outcome of working with unexpected linguistic input (e.g., word expectancy and morpho-syntactic anomalies) and learning from mispredictions. Similarly, Kuperberg et al. (2020) further revealed dissociated biomarkers for semantic prediction violation (N400) and event structure prediction violation (late posterior positivity/P600) in a hierarchical prediction model. Following this account, the present study could elucidate that the function of the P600 effects as word structure sensitivity also applies to the single words reading task with context-sensitive morphological constraints. Meanwhile, for now we cannot rule out the possibility that the P600 is a late grammatical violation-dependent subcomponent of P3 (P3b), indicting a domain-general response to stimuli salience (in the current case, unexpected but interpretable pseudowords). This warrants further modelling investigations and decoding work.

Alternatively, it should be pointed out that it is possible that P600 identified in the selected time window of 500–700 ms could be LPC (late positive complex), which shares the similar distribution as N400 (central-parietal regions). LPC can index the efforts deployed by the brain to integrate the meaning of a stimulus, reflecting the post-lexical evaluation of information mismatch and more explicit processing of semantic information (Laszlo and Plaut 2012; Yum et al. 2016). At present, it is hard to determine whether the late processing is pure semantic re-analysis or mixed with structural analysis with morphological knowledge.

Previous studies demonstrated that the morphological processing of English words could elicit various ERP components such as N250 (Morris et al. 2007) and N400 (Morris et al. 2007; Lavric et al. 2007). However, no later ERP components after 500 ms post word onset was detected. Therefore, one contribution of the present study is that we firstly reported a P600 lexicality effect, which might be associated with a structural difficulty or morphological prediction. Alternatively, it could be linked to stimulus novelty or a second pass on semantics.

Conclusion

In this study, a three-stage process including orthography, semantics, and morphology is proposed to decode the temporal dynamics of Chinese compound word reading. The established model extended the previous mental lexicon theory proposed by Levelt (1989) by demonstrating that Chinese morphological structure might have a quite independent representation at the later stage of post-lexical processing. In particular, the present findings supported the time course of early identification of Chinese orthography as indicated by the null N200 effect (Zhang et al. 2012). And then a process of semantic differentiation between the non-words and words was detected and demonstrated by a N400 lexicality effect, which is in favor of a lexical access view. Furthermore, we contribute to the field by adding that a later ERP component P600 was also detected in reading words presented in isolations, reflecting a re-analysis of semantic or structural signature on Chinese morphological legality. Taken together, the present results showed that single real words, pseudo-words, and non-words can be a viable tool to investigate the temporal dynamics of lexicality effect by combining visual lexical decision paradigm with EEG recordings.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Ji Lu, Prof. Yaxu Zhang, and Dr. Yanjun Wei for their assistance in data acquisition and interpretation.

Author contributions

Fei Gao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. Jianqin Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Funding acquisition. Chenggang Wu: Validation, Data Curation, Writing—Review and Editing. Meng-yun Wang: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis. Juan Zhang: Visualization, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. Zhen Yuan: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00082-FHS and MYRG2018-00081-FHS), the Macao Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT 025/2015/A1 and FDCT 0011/2018/A1), the Higher Education Fund of Macao SAR Government (CP-UMAC-2020-01), National Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of China (12AZD113), and Guangdong Provincial Fund (EF017/FHS-YZ/2021/GDSTCRSKTO).

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Macau and Beijing Language and Culture University Institutional Review Board.

Participant consent

Participants were informed about the study, and consent forms were obtained from each participant before the test.

Consent for publication

All contributing authors agreed to publish this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Juan Zhang, Email: juanzhang@um.edu.mo.

Zhen Yuan, Email: zhenyuan@um.edu.mo.

References

- Bentin S, McCarthy G, Wood CC. Even related potentials associated with semantic priming. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1985;60:340–355. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(85)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentin S, Mouchetant-Rostaing Y, Giard MH, Echallier JF, Pernier J. ERP manifestations of processing printed words at different psycholinguistic levels: time course and scalp distribution. J Cogn Neurosci. 1999;11(3):235–260. doi: 10.1162/089892999563373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JR, Lu D, Burman DD, Chou TL, Jin Z, Peng DL, Zhang L, Ding GS, Deng Y, Liu L. Specialization of phonological and semantic processing in Chinese word reading. Brain Res. 2006;1071(1):197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa DC, Besner D. When do non-words activate semantics? Implications for models of visual word recognition. Mem Cognit. 1998;26:61–74. doi: 10.3758/bf03211370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer H, Crocker MW, Venhuizen NJ, Hoeks JC. A neurocomputational model of the N400 and the P600 in language processing. Cogn Sci. 2017;41:1318–1352. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreiras M, Armstrong BC, Perea M, Frost R. The what, when, where, and how of visual word recognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(2):90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Liu W, Wang L, Peng D, Perfetti CA. The timing of graphic, phonological and semantic activation of high and low frequency Chinese characters: an ERP study. Prog Nat Sci. 2007;17(B07):62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M, Rastle K, Perry C, Langdon R, Ziegler J. DRC: a dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(1):204. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Units of representation in visual word recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101(41):14687–14688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405788101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon D, Dynowska A, Ritter W, Grose-Fifer J. Repetition and semantic priming of non-words: implications for theories of N400 and word recognition. Psychophysiology. 2004;41(1):60–74. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFrancis J (1989) Visible speech: the diverse oneness of writing systems. University of Hawaii Press

- Doyle MC, Rugg MD, Wells T. A comparison of the electrophysiological effects of formal and repetition priming. Psychophysiology. 1996;33(2):132–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1996.tb02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Hu W, Fang Z. Electrophysiological correlates of morphological processing in Chinese compound word recognition. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:601. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Zhang Q, Zhang JX. Does N200 reflect semantic processing? An ERP study on Chinese visual word recognition. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):90794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebach CJ, Friederici AD, Müller K, Cramon DYV. fMRI evidence for dual routes to the mental lexicon in visual word recognition. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14(1):11–23. doi: 10.1162/089892902317205285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitz H, Chang F. Language ERPs reflect learning through prediction error propagation. Cogn Psychol. 2019;111:15–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Wang J, Zhao CG, Yuan Z. Word or morpheme? Investigating the representation units of L1 and L2 Chinese compound words in mental lexicon using a repetition priming paradigm. Int J Bilingual Educ Bilingual. 2021;66:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse SW, Geisser S. On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psychometrika. 1959;24(2):95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gu JX, Yang YM. A neuro-electrophysiological study on productivity of Chinese compounding. Appl Linguis. 2010;3:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P, Brown C, Groothusen J. The syntactic positive shift (SPS) as an ERP measure of syntactic processing. Lang Cognit Process. 1993;8(4):439–483. [Google Scholar]

- Hauk O, Davis MH, Ford M, Pulvermüller F, Marslen-Wilson WD. The time course of visual word recognition as revealed by linear regression analysis of ERP data. Neuroimage. 2006;30(4):1383–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb P, Anderson J. Cross-modal semantic priming: a time-course analysis using event-related potentials. Lang Cognit Process. 1993;8(4):379–411. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JC, Wu CL, Chen HC, Chang YL, Chang KE. Effect of radical-position regularity for Chinese orthographic skills of Chinese-as-a-second-language learners. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;59:402–410. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CH, Tsai JL, Lee CY, Tzeng OJL. Orthographic combinability and phonological consistency effects in reading Chinese phonograms: an event-related potential study. Brain Lang. 2009;108(1):56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juphard A, Carbonnel S, Ans B, Valdois S. Length effect in naming and lexical decision: the multitrace memory model’s account. Curr Psychol Lett Behav Brain Cognit. 2006;19(2):332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kim A, Osterhout L. The independence of combinatory semantic processing: evidence from event-related potentials. J Mem Lang. 2005;52(2):205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR. Neural mechanisms of language comprehension: challenges to syntax. Brain Res. 2007;1146:23–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, Brothers T, Wlotko EW. A tale of two positivities and the N400: distinct neural signatures are evoked by confirmed and violated predictions at different levels of representation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2020;32(1):12–35. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, Donchin E. Preparation to respond as manifested by movement-related brain potentials. Brain Res. 1980;202(1):95–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, Hillyard SA. Reading senseless sentences: brain potentials reflect semantic incongruity. Science. 1980;207(4427):203–205. doi: 10.1126/science.7350657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo S, Plaut DC. A neurally plausible parallel distributed processing model of event-related potential word reading data. Brain Lang. 2012;120(3):271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau EF, Phillips C, Poeppel D. A cortical network for semantics: (de) constructing the N400. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(12):920–933. doi: 10.1038/nrn2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavric A, Clapp A, Rastle K. ERP evidence of morphological analysis from orthography: a masked priming study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19(5):866–877. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.5.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Tsai J-L, Huang H-W, Hung DL, Tzeng OJL. The temporal signatures of semantic and phonological activations for Chinese sublexical processing: an eventrelated potential study. Brain Res. 2006;1121(1):150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Tsai JL, Chiu YC, Tzeng OJ, Hung DL. The early extraction of sublexical phonology in reading Chinese pseudocharacters: an event-related potentials study. Lang Linguist. 2006;7(3):619–635. [Google Scholar]

- Leong CK, Cheng PW, Tan LH. The role of sensitivity to rhymes, phonemes and tones in reading English and Chinese pseudo-words. Read Writ. 2005;18(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJ. Speaking: from intention to articulation. Cambridge: Bradford; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Libben G. Semantic transparency in the processing of compounds: consequences for representation, processing, and impairment. Brain Lang. 1998;61:30–44. doi: 10.1006/brln.1997.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libben G, Gibson M, Yoon YB, Sandra D. Compound fracture: the role of semantic transparency and morphological headedness. Brain Lang. 2003;84:50–64. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Perfetti CA, Hart L. ERP evidence for the time course of graphic, phonological, and semantic information in Chinese meaning and pronunciation decisions. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2003;29(6):1231–1247. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Hua S, Weekes BS. Differences in neural processing between nouns and verbs in Chinese: evidence from EEG. Brain Lang. 2007;103(1):75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lo JCM, McBride C, Ho CSH, Maurer U. Event-related potentials during Chinese single-character and two-character word reading in children. Brain Cognit. 2019;136:103589. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2019.103589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CX, Mao LT, Wang QH. N400 effects in different types of pseudo-words and real words. J Southw China Normal Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2012;37(6):187–192. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon R, Allen M, Osterhout L. Morphological decomposition involving non-productive morphemes: ERP evidence. NeuroReport. 2003;14(6):883–886. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200305060-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechelli A, Gorno-Tempini ML, Price CJ. Neuroimaging studies of word and pseudo-word reading: consistencies, inconsistencies, and limitations. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15(2):260–271. doi: 10.1162/089892903321208196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J, Frank T, Grainger J, Holcomb PJ. Semantic transparency and masked morphological priming: an ERP investigation. Psychophysiology. 2007;44(4):506–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterhout L, Holcomb PJ. Event-related brain potentials elicited by syntactic anomaly. J Mem Lang. 1992;31(6):785–806. [Google Scholar]

- Otten LJ, Sveen J, Quayle AH. Distinct patterns of neural activity during memory formation of non-words versus words. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19(11):1776–1789. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.11.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins T, Dijkstra T, Koeneman O. How Dutch and Turkish–Dutch readers process morphologically complex words: an ERP study. J Neurolinguist. 2019;50:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rinkenauer G, Osman A, Ulrich R, Müller-Gethmann H, Mattes S. On the locus of speed-accuracy trade-off in reaction time: inferences from the lateralized readiness potential. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2004;133(2):261. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD. The effects of semantic priming and word repetition on event-related potentials. Psychophysiology. 1985;22(6):642–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1985.tb01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD. Event-related brain potentials dissociate repetition effects of high-and low-frequency words. Mem Cognit. 1990;18(4):367–379. doi: 10.3758/bf03197126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Barrett SE. Event-related potentials and the interaction between orthographic and phonological information in a rhyme-judgment task. Brain Lang. 1987;32:336–361. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(87)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Doyle MC, Wells T. Word and non-word repetition within- and across modality: an event-related potential study. Cogn Neurosci. 1995;7(2):209–227. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1995.7.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassenhagen J, Fiebach CJ. Finding the P3 in the P600: decoding shared neural mechanisms of responses to syntactic violations and oddball targets. Neuroimage. 2019;200:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. An electrophysiological investigation of the role of orthography in accessing meaning of Chinese single-character words. Neurosci Lett. 2011;487(3):297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Chang J, Qiu Y, Joseph D. The temporal process of visual word recognition of Chinese compound: Behavioral and ERP evidences based on homographic morphemes. Acta Psychol Sin. 2020;52(2):113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Xia Q, Wang L, Peng G. Nouns and verbs in Chinese are processed differently: evidence from an ERP study on monosyllabic and disyllabic word processing. J Neurolinguist. 2016;40:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yum YN, Law SP. Interactions of age of acquisition and lexical frequency effects with phonological regularity: an ERP study. Psychophysiology. 2019;56(10):e13433. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yum YN, Law SP, Mo KN, Lau D, Su IF, Shum MS. Electrophysiological evidence of sublexical phonological access in character processing by L2 Chinese learners of L1 alphabetic scripts. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2016;16(2):339–352. doi: 10.3758/s13415-015-0394-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Peng D (1992) Decomposed storage in the Chinese lexicon. In: Advances in psychology, vol 90. North-Holland, pp 131–149

- Zhang Q, Zhang JX, Kong L. An ERP study on the time course of phonological and semantic activation in Chinese word recognition. Int J Psychophysiol. 2009;73(3):235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JX, Fang Z, Du Y, Kong L, Zhang Q, Xing Q. Centro-parietal N200: an event-related potential component specific to Chinese visual word recognition. Chin Sci Bull. 2012;57(13):1516–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Su IF, Chen F, Ng ML, Wang L, Yan N. The time course of orthographic and semantic activation in Chinese character recognition: evidence from an ERP study. Lang Cognit Neurosci. 2020;35(3):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou A, Yin Y, Zhang J, Zhang R. Does font type influence the N200 enhancement effect in Chinese word recognition? J Neurolinguist. 2016;39:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Packard J, Xia Z, Liu Y, Shu H. Morphological and whole-word semantic processing are distinct: ERP evidence from spoken word recognition in Chinese. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:133. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.