Abstract

Sensory cortices are defined by responses to physical stimulation in specific modalities. Recently, additional associatively induced responses have been reported for stimuli other than the main specific modality for each cortex in the human and mammalian brain. In this study, to investigate a type of consolidation, associative responses in the guinea pig cortices (auditory, visual, and somatosensory) were simultaneously measured using optical imaging after first- or second-order conditioning comprising foot shock as an aversive stimulus and tone and light as sensory stimuli. Our findings indicated that (1) after the first- and second-order conditioning, associative responses in each cortical area were additionally induced to stimulate the other specific modality; (2) an associative response to sensory conditioning with tone and light was also seen as a change in the response at the neuronal level without behavioral phenomena; and (3) when fear conditioning with light and foot shock was applied before sensory conditioning with tone and light, the associative response to foot shock in the primary visual cortex (V1) was decreased (extinction) compared with the response after the first-order fear conditioning, whereas the associative response was increased (facilitation) for fear conditioning after sensory conditioning. Our results suggest that various types of bottom-up information are consolidated as associative responses induced in the cortices, which are traced repetitively or alternatively by a change in plasticity involving facilitation and extinction in the cortical network. This information-combining process of cortical responses may play a crucial role in the dynamic linking of memory in the brain.

Keywords: Associative response, Higher-order conditioning, Sensory cortex, Optical imaging, Guinea pig

Introduction

According to electrophysiological recordings, pathological results, and neuroimaging studies, long-term memory is stored in the cerebral cortex. These findings indicate that learning and experience activate cortical areas for memory preservation. Understanding how learning modifies the functional properties of cortical areas is necessary to explain how memory is consolidated in the brain and, in particular, the mechanisms of memory association.

In the sensory area of the cerebral cortex, information from peripheral sensory inputs is spatially expressed while geographical correspondence is maintained. It has been experimentally shown that this spatial expression in the cerebral cortex causes plastic changes reflecting learning and experience, even in mature individuals. These associative memories are often studied using sensory conditioning comprising the pairing of tone and light with fear conditioning involving electric foot shock, and behavioral experiments using this paradigm are performed to evaluate conditioning using heart rate and behavioral changes as indicators, as well as electroencephalography and cell activity. In addition, many studies have used response measurement to investigate the plastic change in cell activities in the network. Sensory preconditioning, comprising first-order sensory conditioning with Tone-light and second-order fear conditioning with Light-shock, elicits a conditioned response (shock response) that is similar to that elicited by light (Rizley and Rescorla 1972). Moreover, some crucial studies that used higher-order conditioning paradigms have also been performed (Rescorla and Furrow 1977; Holland 1977; Helmstetter and Fanselow 1989; Gewirtz and Davis 2000; Headley and Weinberger 2015, Lay et al. 2018).

It has recently been reported that receptive fields in the auditory cortex are plastically changed by fear conditioning, with the best frequency strongly tuned to the frequency used for the conditioning, if those frequencies are relatively close to one another (Bakin and Weinberger 1990; Edeline and Weinberger 1993; Edeline et al. 1993; Ide et al. 2012). Furthermore, the promotion of long-term potentiation by activation of the amygdala, related to aversion and the release of endogenous acetylcholine derived from the activity, is reported to be important for the formation of information association between the somatosensory area and another cortex (Weinberger and Bakin 1998; Ji and Suga 2008; Ide et al. 2013, Lopez et al. 2015). In our previous study, after conditioning with tone and electric foot shock, the auditory cortex responded to foot shock alone, as identified using an optical imaging method with a voltage-sensitive dye (Ide et al. 2013). Thus, the response associated with tactile and auditory information is induced not only in the main sensory cortex but also in the other sensory cortex, by fear conditioning. In rodents, cross-modal cortical responses to sensory stimuli have been reported to occur in the non-dominant sensory cortex (Iurilli et al. 2012), and cortico-cortical or thalamo-cortical pathways have also been observed (Henshuke et al. 2015). Headley and Weinberger (2015) showed that, when a tone and light pair was given as the first conditioning in rats, with a light and foot shock pair as the secondary conditioning, the associative response to tone in the visual cortex V1 was higher than that in naïve rats. In addition, the associative response to visual stimuli in the auditory cortex was induced by a similar conditioning paradigm (Kubota et al. 2017). However, the cellular-level information representation (visualization) of memory in the cortico-cortical association has not yet been clarified. Therefore, clarification of the formation of memory consolidation represented as a change in the dynamic memory trace in the cortico-cortical network by conditioning would significantly help to explain memory association in the brain.

In this study, to investigate induction of the intercortical association, first- and second-order conditioning was performed in guinea pigs by pairing three stimuli: foot shock as an aversive stimulus (unconditional stimulus [US]) and tone and light as sensory stimuli (conditional stimulus [CS]). The induction of the associative response to the three stimuli alone was then investigated in the auditory cortex, visual cortex, and somatosensory cortex. The responses at six areas in the three sensory cortices -primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) in the somatosensory area, V1 and the lateral visual field (LV) in the visual area, and A1 and the dorsocaudal field (DC) of the auditory cortex in the auditory area- were simultaneously measured as a spatiotemporal response by using an optical imaging method. Next, we investigated how associated responses were induced depending on the first and second conditioning and the formulation mechanism of memory trace was discussed by considering the associative response as representing a dynamic consolidation change between cortices.

Methods

Subjects

The experimental subjects were male guinea pigs (Hartley, SLC) weighing 200–300 g and aged 2–4 weeks old. The animals were housed under a 12-/12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 8 a.m.) with ad libitum food and water intake. All experiments were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Tamagawa University (H14-C).

Conditioning

In this work, first- and second-order conditioning was performed by using three sensory stimuli: light and tone stimuli elicit no fear response (a heart rate change or freezing), whereas electric foot shocks elicit a fear response. To minimize contextual fear, the animals were acclimated in a darkroom chamber for 2 h before the conditioning. The animals were lightly anesthetized with urethane (0.2 g/kg, intraperitoneal) to inhibit body movement and were conditioned in a dark chamber while fixed in an animal hammock. Electrocardiographic (ECG) electrodes were attached to the forelegs, and the condition of each animal was monitored by ECG throughout the experiment. As a stimulus for the first- and second-order conditioning, light was emitted from a white LED placed on the ceiling of the chamber. Tone stimulation (8 kHz) was generated from a high-frequency speaker (Tucker-Davis Technologies) located in the chamber wall on the right side of the animal. The electrodes for the shock were attached to the hind legs using conductive paste. The electric shock was generated by using a stimulator (SEN-7203; Nihon Kohden) and was applied to the hind legs through an isolator (SS-202 J; Nihon Kohden). The current intensity was adjusted to between 1.5 and 1.9 mA.

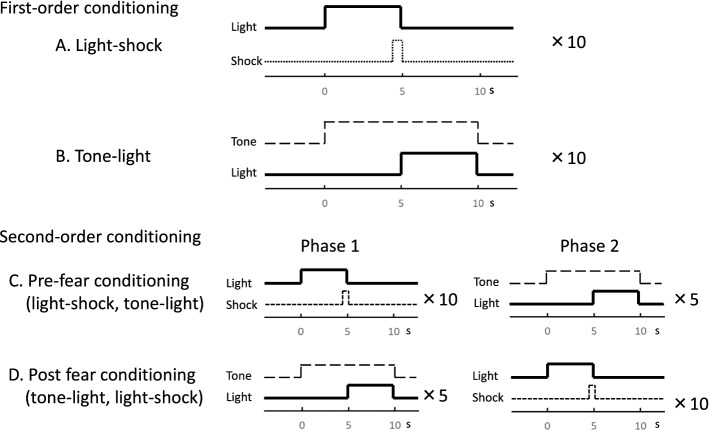

The conditioning protocols performed before the optical recording of the cortical responses are shown in Fig. 1. Two types of first-order conditioning were used for this study. One was fear conditioning (CS1-US), which was a paired stimulus comprising light (white LED, 5 s) and Shock (0.7 mA, 0.5 s), shown as Light-shock conditioning in Fig. 1A. The other was sensory conditioning (CS2-CS1), which was a paired stimulus comprising tone (8 kHz, 10 s) and light (5 s), shown as Tone-light conditioning in Fig. 1B. The Light-shock and Tone-light pairings were applied 10 times each. The interval between each trial was randomly set at between 61 and 180 s for each type of conditioning. On the other hand, two types of second-order conditioning were used. One is shown as Pre-fear conditioning in Fig. 1C and comprised 10 applications of Light-shock (US-CS1) in phase 1 on the first day preceding 10 applications of the sensory condition Tone-light (CS2-CS1) in phase 2 on the next day. The other is shown as Post-fear conditioning in Fig. 1D and is called sensory preconditioning (Rizley and Rescorla 1972). It involved 10 applications of Tone-light (CS2-CS1) in phase 1 on the first day and was followed by 10 applications of Light-shock (US-CS1) in phase 2 on the second day. We returned the animals to their home cages after confirming that they were awake and drinking water. ECG was performed to confirm the conditioned response. For these subjects, the CS and US were never presented before the optical recording.

Fig. 1.

Protocol of conditioning paradigms using light, tone, and foot shock and of test sessions. A Light-shock: first-order conditioning, pairing of light (white LED, 5 s) and electric foot shock (0.7 mA, 0.5 s). B Tone-light: pairing of tone (8 kHz, 10 s) and light (white LED, 5 s). C Pre-fear conditioning: second-order conditioning comprising Light-shock preceding Tone-light. D Post-fear conditioning: second-order conditioning comprising Light-shock following Tone-Light

Optical recording

To measure the responses to sensory stimuli by optical imaging after conditioning, the animals were prepared using the following procedure. The body temperature of each animal was maintained at 37 °C during the experiment by using the MK-900 blanket system for animals (Muromachi Kikai Co. Ltd.). Each animal was anesthetized with urethane (1.0 g/kg, intraperitoneal). The trachea was cannulated and the head clamped. The scalp was detached, a hole (approximately 2 × 3 cm) was drilled in the left temporal bone, and the dura and arachnoid membrane were removed. Whole cortices of the exposed area were stained for 50–60 min with the voltage-sensitive dye di-4-ANEPPS (0.12 mg/ml, dissolved in saline; Promo Cell Co. Ltd.) (Devonshire et al. 2010). Then, the animal was artificially respirated after paralysis induction with pancuronium bromide (0.2 mg/kg, intramuscular). The experiments were carried out in a dark soundproof room. At the end of the experiment, each animal was administered an overdose of sodium pentobarbital and cardiac arrest was induced.

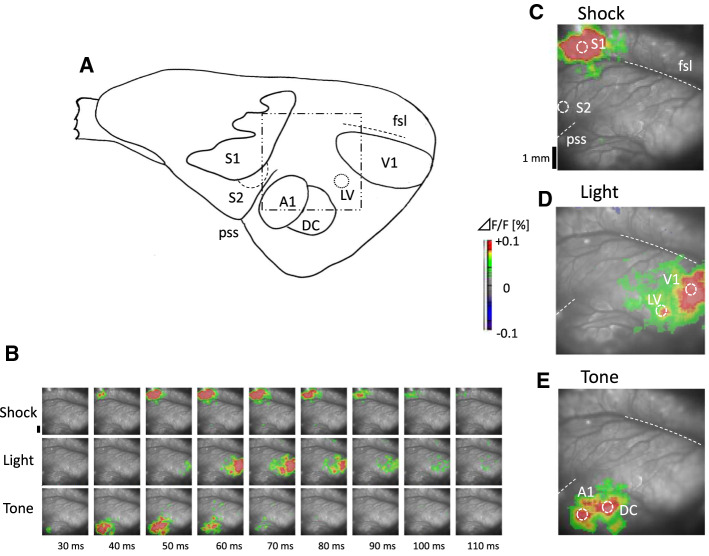

To investigate the effects of conditioning on the somatosensory cortex, visual cortex, and auditory cortex, the responses to each stimulus were measured by optical imaging after conditioning. The cortical responses of inter-subjects were adjusted to keep the consistence of the reflected fluorescence intensity F constant by changing the light intensity of the halogen lamp as the light source. Because the magnitude of response was measured as the ratio ΔF/F, where F and ΔF are the light intensity at rest and the change in intensity induced by neuronal responses, respectively. Figure 2A shows a schematic diagram of the cortical area, with the measurement region for optical recording marked (1 cm2), which included the visual, somatosensory, and auditory cortices. The test session was scheduled on the day after the first- or second-order conditioning. All sensory stimuli for the tests were performed with a duration of 50 ms. The light stimulus was presented to the right eye using a white LED at a distance of about 5 cm from the eye at 30–40 lx. Tone stimulation was presented at 8 kHz and 50 dB. Foot shock was performed as for conditioning. To prevent an excessive over-shock response, the current intensity was set at 0.5–0.7 mA. The experimental systems are detailed in our previous articles (Ide et al. 2012, 2013). A 100 × 100 channel CMOS imaging device (MiCAM ULTIMA-L; Brainvision Inc., Tokyo) was used to record the fluorescent signals from the brain surface. The amplified optical image data were sampled via a 12 bit A/D converter and sent to a workstation with a 2.0 ms time resolution. The respirator was stopped for 2 s to eliminate the oscillation noise originating from respiration. Noise originating from heart pulsation was reduced by synchronizing the recording with the R wave in the ECG and subtracting the recording without the stimulus from that with the stimulus. The illumination was turned on only during the recording period to minimize dye bleaching. To obtain a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio, the optical data of 16 trials were averaged.

Fig. 2.

A schematic diagram of the cortical area and responses in the guinea pig. A A schematic diagram of the cortical area including the somatosensory cortices (S1 and S2), visual cortices (V1 and LV), and auditory cortices (A1 and DC). The square with the dotted and dashed line indicates the recording area for optical imaging (1 × 1 cm). The map shows the location of each cortex, in reference to Wallace et al. (2000). B Cortical activations in response to foot shock (upper), light (middle), and tone (lower) in the naïve guinea pig. The pseudocolor version of each image was superimposed on the cortical surface with the color corresponding to ΔF/F defined by the color bar. C Normal activity in response to foot shock in the primary (S1) and secondary (S2) somatosensory cortices corresponding to 46 ms in the upper figures of A. The scale bar on the left side is 1 mm. fsl, fissura sagittalis lateralis (lateral sulcus); pss, pseudosylvian sulcus. D Normal activity in the primary (V1) and secondary (LV) visual cortices 62 ms from the start of the light stimulus in the middle images of A. E Normal activity in the auditory cortices (A1 and DC) 46 ms from the start of the tone stimulus in the lower images of (A). The responses depicted in C-E are shown with a suitable time delay to discriminate the respective responses in each sensory area

Data analysis

The following processing was applied to the optical recording data. To eliminate the noise originating from heart pulsation, data recorded without any stimulus was subtracted from data recorded with each stimulus. Next, to reduce noise, such as shot noise, a 5 × 5 pixel spatial median filter was used. To characterize the responses from each area, a region of interest (ROI) was assigned to S1, S2, V1, LV, A1, and DC, respectively. All of the ROIs had a diameter of 0.8 mm and their center was established to contain the response epicenter and to cover as many responding pixels as possible. Typical examples of ROIs are shown in Fig. 2C–E. From the response in the ROI, the latency of the response to the rise of the waveform and the time to the peak response were calculated. The response latency was measured as the time from stimulus onset to when the differentiated signal exceeded the positive or negative maximal baseline value. The limited baseline was 3 times of standard deviation of the time width at 30–0 ms before the onset of the stimulus. The differentiated signal was obtained using the equation d(ΔF/F)/dt[n] = ΔF/F[n]—ΔF/F[n—1], where n is the sample number, and was normalized to the response peak amplitude (Nishimura and Song 2012). The peak was set at a point where the differentiated signal after the stimulation onset was near 0 and the signal differentiated twice had a minimum value. For statistical analysis, multiple comparisons were performed by using the Bonferroni multiple comparison test for ECG data, and Steel–Dwass multiple comparison test for peak ΔF/F to each cortical area. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Heart rate measurement

To determine whether the animals displayed a heart rate change as a fear effect, we performed ECG recording during conditioning. The results are shown in Fig. 3A–D. The largest peak of the ECG amplitude is called the R wave. The variation in the R-R interval was used as an index of the heart rate change. Therefore, the ΔRR, that is, the change rate of the R-R interval from the resting state, was investigated. The ΔRR was defined as: ΔRR = (RR(0)—RR(c))/RR(0). RR(0) was the mean value of 10 R–R intervals from 10 s before the stimulus onset as the resting-state heart rate, whereas RR(c) was the mean value of the 10 R–R intervals immediately before the stimulus onset. In Tone-light, RR(c) was the mean value of 10 R–R intervals immediately before the tone stimulus. An outlier test (Smirnov-Crubbs method) was performed for each trial plot in A–D. Figure 3A shows the heart rate change during Light-shock conditioning (n = 11). Figure 3B shows the heart rate change in Tone-light conditioning as phase 2 of Pre-fear conditioning (n = 8). Figure 3C shows the heart rate change in Tone-light pairing (n = 6). Figure 3D shows the heart rate change in Light-shock conditioning as phase 2 of Post-fear conditioning (n = 8). One-way repeated measures ANOVA (analysis of variance) showed significant differences among Light-shock (F (2.8, 28.0) = 3.61, P = 0.027, partial η2 = 0.27), Tone-light (Phase2) (F (1.9, 13.7) = 3.90, P = 0.046, partial η2 = 0.35), Light-shock (Phase2) (F (1.7, 12.2) = 5.0, P = 0.029, partial η2 = 0.41). Non-significant difference was found for Tone-light (F (1.8, 9.0) = 1.28, P = 0.319, partial η2 = 0.20). However, using Mauchly's sphericity test to check for homoscedasticity, the sphericity assumption was rejected for Light-shock (P = 0.010), Tone-light (P = 0.007), and Light-shock (Phase 2) (P = 0.033). On the other hand, The sphericity assumption was not rejected for Tone-light (Phase 2) (P = 0.190). Therefore, except for Tone-light (Phase 2), an ANOVA was performed using degrees of freedom corrected by Greenhouse–Geisser ε. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Heart rate changes in guinea pigs during conditioning. A Heart rate change in Light-shock conditioning (n = 11) in phase 1 of Pre-fear conditioning. B Heart rate change in Tone-light conditioning in phase 2 of Pre-fear conditioning (n = 8). C Heart rate change in Tone-light conditioning (n = 6) in phase 1 of Post-fear conditionig. D Heart rate change in Light-shock conditioning in phase 2 of Post-fear conditioning (n = 8). The change in the mean R-R interval from the resting state to immediately before stimulation for each trial during the condition compared with that before conditioning was measured. Gray dots with lines represent the mean of the data for each trial from individual guinea pigs. The error bar is SEM. (*) P < 0.05, (**) P < 0.01. P values were obtained using the Bonferroni multiple comparison test

After that, Bonferroni multiple comparison test for each trial was applied to results for conditionings where significant differences were obtained by ANOVA. Figure 3A, the heart rate increase was observed for each trial as increase of the number of the trial and a significant difference was found for the 4th (P = 0.031) and 10th (P = 0.021) trials versus the 1st trial. Figure 3B, the heart rate was decreased for each trial and a significant difference was found for the 5th (P = 0.019) and 10th (P = 0.026) trials versus the 1st trial. These results showed that the effect of Light-shock (CS1-US) conditioning on physical behavior can still be established after five or more trials. Nonetheless, the effect was decreased after more than five trials on Tone-light (Phase2), which suggested an extinction of the aversive physical response by Pre-fear conditioning.

On the other hand, Fig. 3C shows that there were no significant changes in heart rate for each trial with Tone-light conditioning (CS1-CS2). However, when Tone-light conditioning was applied before Light-shock (CS-US) (sensory preconditioning; Rizley and Rescorla 1972), there was a larger increase in heart rate changes at the 10th trial than at the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th (P = 0.049, P = 0.003, P = 0.004, P = 0.006) trials (Fig. 3D). In addition, the magnitude was larger than that after only Tone-light (CS1-CS2), which suggested facilitation of an aversive physical response by Post-fear conditioning.

Optical measurement

Cortical responses to the three stimuli measured by optical recording with no conditioning (naïve) are shown as a representative example in Fig. 2B and responses in each ROI in Fig. 4A. In addition, the responses after application of the first- and second-order conditioning are shown in Fig. 4B–F. In Fig. 4, gray line showed single trace of response and black line showed mean responses. To compare the response changes according to each type of conditioning among the three sensory stimuli, the magnitude of the peak response for the three stimuli are presented in Fig. 5, as a summary of the results of Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Single and Average responses of the ΔF/F to the three stimuli (foot shock, light, tone) after conditioning. Time courses of responses in the ROI induced by each type of conditioning. A Naïve (n = 5). B Light-shock (n = 6). C Tone-light (n = 5). D Pre-fear conditioning (n = 8). E Post-fear conditioning. (n = 8). The gray traces show single response and the black trace shows the population mean. The vertical line marks the onset time of each sensory stimulus. For each type of conditioning, the diagram represents 50 ms as duration of each stimulus and is set at the bottom of the vertical line. The horizontal scale bar represents 100 ms and the vertical scale bar represents 0.1% ΔF/F intensity in the calibration. † and—represent the significant positive and the significant negative response, respectively (P < 0.05; Student’s t-test for difference from baseline level). Those duration times were shown beside of † or -

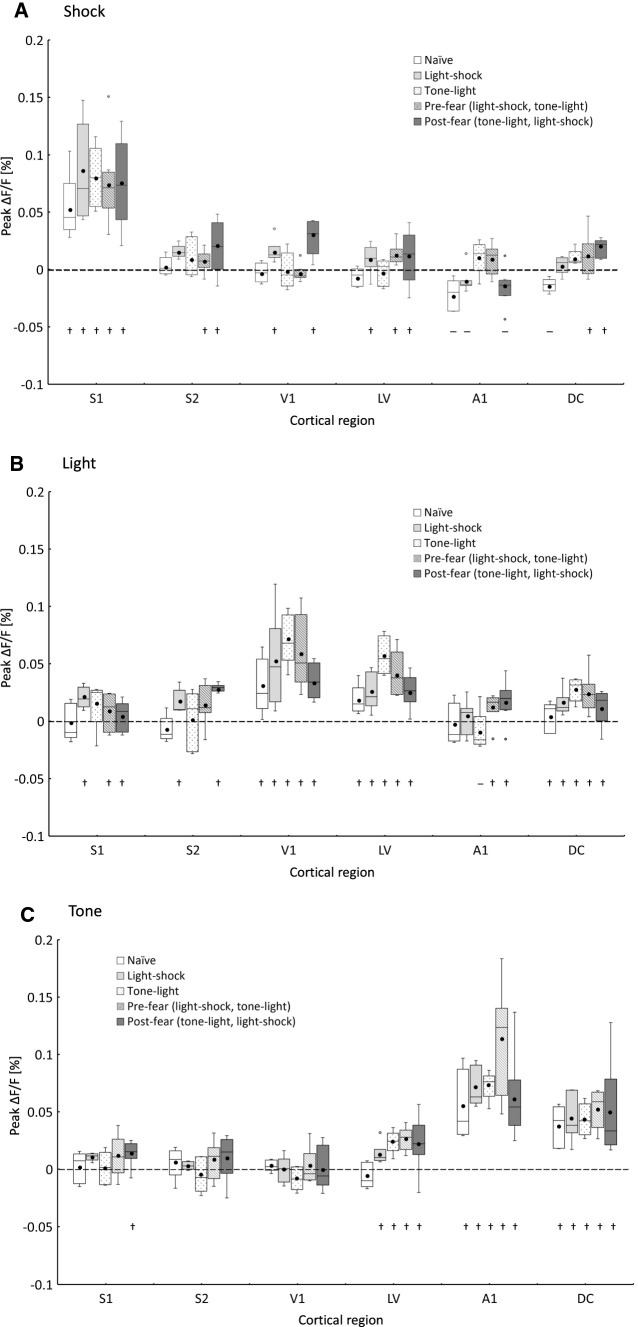

Fig. 5.

Associative cortico-cortical responses depending on the conditioning. Box plot of peak magnitudes of the associative responses in the ROI of each cortex (S1, S2, V1, V2, A1, and DC) to the three stimuli (A, foot shock; B, light; and C, tone stimulus) after each conditioning are shown based on the results of Fig. 4. Open boxes represent as Naïve (group). Light gray boxes are indicated as Light-shock. Dotted boxes are indicated as Tone-light. Hatched boxes are indicated as Pre-fear. Gray boxes are indicated as Post-fear. Each Box represents the interquartile range between first and third quartiles, whereas the whisker represents the maximum and the minimum values in median ± 1.5 × IQR, with IQR being the difference between the third and first quartiles. The median value and the mean value were represented by the horizontal line and black dot in the box, respectively. The circles represent data which excluded in median ± 1.5 × IQR. † and—represent the positive and the negative significant response, respectively as Fig. 4 (P < 0.05; Student’s t-test for difference from baseline level)

To determine the time window of significant response, we calculated sequential t-score at each time after stimuli onset. “ †” represents a positive response and “-" represents a negative waveform. Those duration times were shown beside of them.

Cortical responses without conditioning (naïve)

First, cortical responses to sensory stimulation were measured by optical recording in naïve guinea pig brains with no conditioning (n = 5). Figure 4A shows the cortical activities in response to foot shock, light, tone stimulus in naïve. From top to bottom, single (gray) and average (black) time course responses from six cortical sensory areas (S1, S2, V1, LV, A1, and DC) are shown. The time course of the responses obtained from − 50 ms to 300 ms for the initial time of stimulation. A positive response to foot shock was evident only in S1, at an average latency of 30.0 (29) ± 1.5 ms, whereas a negative response was observed in A1 at 57.3 (50) ± 7.8 and DC at 58.7 (62) ± 9.0 ms. Next, significant positive response to light were seen in V1 at 41.2 (40) ± 2.1 ms and LV 51.0 (53) ± 6.1 ms, and was also observed in DC at 40.0 (38) ± 11.5 ms. Finally, significant responses to tone were observed only in the auditory cortex A1 and DC at 25.6 (24) ± 2.1 ms and 31.2 (34) ± 2.4 ms, respectively. The error shows standard error (SEM) and he number in parentheses shows median value. Consequently, in the naïve condition, the foot shock stimulus induced a negative response in A1 and DC.

Light-shock as first-order fear conditioning

Next, Fig. 4B shows the time courses of the responses to the three sensory stimuli after a first-order fear conditioning comprising light and foot shock (n = 6). In this experiment, freezing and heart rate changes, as physical responses to fear conditioning, were evident behavioral responses, showing that fear conditioning was established. Significant responses to foot shock appeared in S1 at an average latency of 34.3 (32) ± 1.8 ms and were also observed in V1 at 32.5 (37) ± 4.3 ms and in LV at 46.7 (44) ± 4.2 ms. A negative response was seen in A1 at 66.0 (72) ± 5.0 ms. On the other hand, significant responses to light were observed in V1 at 43.6 (40) ± 9.3 ms and in LV at 38.0 (42) ± 5.0 ms and were also seen in S1 at 42.4 (50) ± 6.2 ms and S2 at 66.5 (67) ± 11.9 ms. Additionally, a response was also evident in DC at 59.6 (60) ± 12.0 ms, as seen without conditioning. Significant responses to tone were observed in the auditory cortex A1 and DC at 25.0 (25) ± 1.1 ms and 33.0 (34) ± 2.3 ms, respectively. In addition, a response was in the visual cortex LV at 31.2 (34) ± 4.0 ms but not in V1. The error is SEM. The number in parentheses is median.

Tone-light as first-order sensory conditioning

Figure 4C shows the responses after a first-order sensory conditioning comprising tone and light (n = 5). In this experiment, no freezing or heart rate changes as the physical responses to fear conditioning were observed (Fig. 3C). Therefore, the behavioral results suggested that the conditioning could not be established. However, our subsequent results from optical recording in the sensory cortex showed an effect of the conditioning. The significant response to foot shock was found only in S1 at an average latency of 31.5 (30) ± 1.8 ms. However, significant responses to light were observed not only in V1 at 44.8 (46) ± 2.7 ms and in LV at 46.8 (50) ± 2.9 ms, but also in A1 at 39.0 (39) ± 6.0 ms and in DC at 56.8 (48) ± 12.2 ms. On the other hand, significant responses to tone were observed in the auditory cortex A1 at 22.0 (24) ± 1.9 ms and in DC at 32.4 (32) ± 1.9 ms, and not in V1, but in LV at 37.0 (35) ± 2.7 ms at the same time as the response in DC. The error shows SEM. The number in parentheses is median.

Pre-fear conditioning (Light-shock/Tone-light) as second-order conditioning

Figure 4D shows the results (n = 8) of fear conditioning with light and foot shock, followed by sensory conditioning with tone and light. Significant responses to foot shock were found not only in S1 at 33.2 (33) ± 1.6 ms, but also in LV at 43.0 (42) ± 9.0 ms and DC at 31.7 (26) ± 4.0 ms, responses that were not observed in the cortices of naïve animals. On the other hand, significant responses to light were observed not only in V1 at 47.5 (42) ± 8.6 ms and in LV at 58.2 (56) ± 6.1 ms, but also in S1 at 60.4 (62) ± 10.5 ms and in S2 at 53.2 (52) ± 10.2 ms. In addition, significant responses were observed in A1 at 50.0 (68) ± 13.4 ms and in DC at 61.3 (57) ± 5.2 ms. Finally, significant responses to tone were observed not only in A1 at 27.1 (26) ± 1.5 ms and in DC at 41.8 (38) ± 6.6 ms, but also in LV at 39.0 (39) ± 3.0 ms. The error shows SEM. The number in parentheses is median.

Post-fear conditioning (Tone-light/Light-shock) as second-order conditioning

Next, Fig. 4E shows the responses (n = 8) when sensory conditioning with tone and light, “sensory preconditioning” (Gewirtz and Davis 2000), was applied, followed by fear conditioning comprising aversive foot shock. Significant responses to foot shock were observed in S1 at 28.5 (29) ± 1.3 ms and in S2 at 60.5 (56) ± 8.5 ms. In addition, significant responses appeared in V1 at 20.3 (17) ± 3.4 ms and in LV at 30.3 (32) ± 9.2 ms, as well as a negative response in A1 at 44 (45) ± 3.2 and a positive response in DC at 30.8 (26) ± 12.3 ms. On the other hand, significant responses to light were observed not only in V1 at 49.1 (48) ± 2.4 ms and in LV at 56.3 (54) ± 3.3 ms, but also in S1 at 84.8 (30) ± 7.7 ms and in S2 at 54.0 (44) ± 8.4 ms. In addition, significant responses were observed in A1 at 58.0 (54) ± 3.7 ms and in DC at 46.4 (48) ± 4.6 ms. Moreover, significant responses to tone were observed not only in A1 at 25.5 (26) ± 1.1 ms and in DC at 30.7 (31) ± 1.3 ms, but also in LV at 50.0 (46) ± 5.0 ms. However, the significant response in V1 seen in the first fear conditioning disappeared. Furthermore, the significant response to tone also appeared in S1 at 57.7 (50) ± 14.0 ms. The error shows SEM. The number in parentheses is median.

Associative cortico-cortical responses depending on the conditioning

To compare the differences in responses according to conditioning among the three sensory stimuli, the magnitude of the peak response to the three stimuli (A, foot shock; B, light; and C, tone) are summarized in Fig. 5 from the results of Fig. 4. The minimum or maximum value of the response between 0 and 200 ms was determined to be the magnitude of the peak response. Firstly, the results of the three-factor analysis of variance (Three-way ANOVA (no correspondence)) showed that the main effects of stimulus, Cortical area, and conditionings were all significant; (F (2, 480) = 7.0, P < 0.005, partial η2 = 0.028), (F (5, 480) = 10.9, P < 0.005, partial η2 = 0.010), and (F (4, 480) = 11.0, P < 0.005, partial η2 = 0.084), respectively. Furthermore, the first-order interaction between Stimuli and Cortical area was significant (F (10, 480) = 58.3, P < 0.005, partial η2 = 0.548). In addition, the second-order interaction of Stimuli, Cortical area, and Conditionings was significant (F (40, 480) = 1.5, P < 0.005, partial η2 = 0.113).

Next, a multiple comparison test (Steel–Dwass test) was performed between conditioning in each stimulus and cortical area, and the results showed that there were significant differences between Light-shock and Pre-fear, and between Pre-fear and Post-fear. From the results shown in Fig. 5A–C, we investigated the association of the responses among cortical areas induced by each type of conditioning.

Figure 5A shows the magnitude of the response to foot shock in the S1, S2, V1, LV, A1, and DC areas after each conditioning. The mean responses in S1 were increased by Light-shock, Pre-fear, and Post-fear conditioning, which was comprised of foot shock, for naïve. Next, the responses in V1 were induced after Light-shock and Post-fear conditioning. We considered these to be “associative responses”. When Pre-fear conditioning was applied, the associative response to foot shock in the visual cortex V1 (hatched box) was significant decreased compared with that after Light-shock (light-gray box) (P = 0.022). On the other hand, Post-fear conditioning increased the associative response (gray box) and it was significant with the application of Pre-fear conditioning (P = 0.015). In addition, an associative response (hatched box) was not observed in V1 and LV in response to Tone-light without foot shock. Moreover, a negative response appeared in A1 under naïve, Light-shock, and Post-fear conditions. Interestingly, associative responses were decreased and increased in the negative direction in the same manner as shown in V1 after the second-order conditioning. Furthermore, the associative responses positively appeared in DC after Pre- and Post-fear conditioning (P = 0.048, P = 0.030).

Figure 5B shows the magnitude of the response to light in S1, S2, V1, LV, A1, and DC after each type of conditioning. The mean responses in V1 and LV were increased by Light-shock, Tone-light (negative), and Pre-fear conditioning, but not by Post-fear conditioning. Furthermore, the associative responses (light-gray box) in S1 and S2 were induced after Light-shock and pre- and Post-fear conditioning. On the other hand, the associative response in A1 was induced by Tone-light, Pre-fear, and Post-fear conditioning. Moreover, the response in DC in naïve animals was induced by all conditioning, but mean value decreased by Post-fear conditioning was shown at low level, similar to the associative responses in V1.

Figure 5C shows the magnitude of the response to tone in the S1, S2, V1, LV, A1, and DC areas after each type of conditioning. The mean responses in A1 were increased after Pre-fear conditioning but were not increased after Post-fear conditioning. In addition, the associative responses in S1 to tone were induced only after Post-fear conditioning. On the other hand, there was not a significant response under naïve conditions in LV, an associative response was induced with each type of conditioning.

Discussion

To investigate the associative consolidation of memory traces in the sensory cortical network, the induction of associative responses among sensory cortices was measured by first- and second-order conditioning involving three stimuli, namely, foot shock as a fear stimulus and light and tone as sensory stimuli. By using an optical imaging method with a voltage-sensitive dye, responses were simultaneously examined in the somatosensory area S1 and S2, the visual area V1 and LV, and the auditory area A1 and DC. By comparing these associative responses to the naïve response and analyzing the dependence of the induction on the types and sequences of the first- and second-order conditioning, we determined how intercortical associations were consolidated and appeared among sensory cortices.

Naïve responses in cortices for sensory inputs

Cortical responses to sensory stimuli were measured by optical recording in naïve guinea pig brains with no conditioning (Fig. 4A). Significant responses to foot shock positively appeared in S1 and negatively appeared in A1 and DC with a long delay. In addition, significant responses to light were observed not only in V1 and LV, but also in DC, with a long delay. On the other hand, a significant response to tone was observed in A1 and DC with a short delay. These results showed that sensory information was translated not only to the main stream for the sensory modality, but also to the early stage of information processing for the other modality.

These results are consistent with those of previous studies in rats (Wallace et al. 2004), ferrets (Cappe et al. 2009, Bizley et al. 2009), and gerbils (Kobayasi et al. 2013). Studies supporting our results concerning anatomical projectile pathways have also been reported (Campi et al. 2010; Henschke et al. 2015; Morrill and Hasenstaub 2018; Nakata et al. 2020). In particular, Iurilli et al. (2012) showed responses in three sensory areas to sensory stimuli corresponding to our findings indicating negative responses to foot shock in A1 and DC. These results suggest that there were originally either direct projections or feedback projections from somatosensory pathway to auditory system. In addition, the response to light observed in DC suggests that DC plays an important role in the visuo-auditory interaction influenced by visual information downstream of the visual system. This result supports the report by Nishimura and Song (2012).

Associative responses after first-order conditioning comprising fear conditioning (Light-shock) and sensory conditioning (Tone-light)

First, to investigate the differences in associative responses between types of first-order conditioning, we applied two types of conditioning, fear conditioning (Light-shock) and sensory conditioning (Tone-light).

After Light-shock comprising light and foot shock, significant responses to foot shock were observed not only in the somatosensory cortex S1, in addition to a negative response in A1 in naïve animals, but also in the visual cortex V1 and LV (Fig. 4B, light-gray box in Fig. 5A). These results were similar to those of our previous study that indicated that the associative response to foot shock was also induced in the auditory cortex A1 after fear conditioning using tone as a sensory stimulus and foot shock as a fear stimulus (Ide et al. 2012). On the other hand, significant responses to light were additionally induced in the somatosensory cortex S1 and S2, in addition to the V1, LV, and DC observed in naïve cases (Fig. 4B, light-gray box in Fig. 5B). These results suggest that plastic changes were induced by fear conditioning, which was formed as associative responses between somatosensory and visual regions in the network for information processing. In addition, a significant response to tone that was not involved in the conditioning was additionally induced in LV, in addition to A1 and DC (Fig. 4B, light-gray box in Fig. 5C). It might be considered that the visuo-auditory relationship was observed to LV, a higher associative stage.

Next, during the application of Tone-light conditioning, no freezing or heart rate changes, as physical responses to fear conditioning, were observed (Fig. 3C). However, after application of Tone-light conditioning, significant responses to light were additionally observed in A1 (negative), besides that in V1, LV, and DC in the naïve brain (Fig. 4C, hatched box in Fig. 5B). On the other hand, a significant response to tone was induced in LV (Fig. 4C, hatched box in Fig. 5C). The results showed that an associative response to tone was seen in the LV area instead of V1. This result corresponds to previous findings showing that the associative response to visual stimuli is induced in the auditory cortex in the mouse brain and that the associative response to complex auditory stimuli is observed in the visual cortex (Ogi et al. 2019). Moreover, the significant responses to foot shock, which was not involved in Tone-light conditioning, the response in A1 and DC observed in the naïve brain disappeared (Fig. 4C, light-gray box in Fig. 5C). It might also be considered that the response based on the auditory-somatosensory connection in A1 and DC was covered or weakened by induction of a auditory-visuo association. Interestingly, this phenomenon associated with Tone-light conditioning was very similar to other findings indicating that the response to tone modulated by Light-shock conditioning in LV was modulated (Fig. 4B).

These results suggest that associative responses were induced by not only Light-shock conditioning with behavioral changes, but also by Tone-light conditioning without behavioral changes. The associative response depended on stimulus components during the conditioning, which modulated the related response for the other stimulus modality.

Associative responses induce second-order conditioning

Finally, to investigate the influence of the order of an alternative pairing of sensory stimuli on memory traces, we performed two types of second-order conditioning comprising fear conditioning and sensory conditioning. One comprised Pre-fear conditioning (Light-shock/Tone-light), whereas the other comprised Post-fear conditioning (Tone-light/Light-shock).

Pre-fear conditioning (Light-shock/Tone-light)

When Light-shock was applied and followed by Tone-light, significant responses to foot shock positively appeared not only in S1 and LV, but also in S2, and DC, however disappeared in V1 (Fig. 4D, hatched box in Fig. 5A). These results show that the associative response induced by the preceding fear conditioning were modulated by the subsequent sensory conditioning comprising light and tone without fear. In Pre-fear conditioning, by linking the associative factor to the response to light, A1 and DC of the auditory cortex consequently positively responded to foot shock. On the other hand, significant responses to light were observed not only in V1, LV, S1, S2 and DC, but also in A1, however disappeared in S2 (Fig. 4D, hatched box in Fig. 5B). In addition, significant responses to tone were observed not only in A1 and DC, but also in LV (Fig. 4D, hatched box in Fig. 5C). From these results, we consider that the second-order conditioning that involved the pairing of three stimuli modulated boosted the plasticity of the network connection, so that associative responses were induced not only in the sensory area in which the stimulus is the main modality, but also in the other related areas in conditioning. Associative responses of the somatosensory, visual, and auditory cortex occurred for each stimulation. These results showed that information from somatosensory, visual, and auditory inputs were integrated and appeared as associative responses in three cortices in response to Pre-fear conditioning. Our findings thus suggest that memory consisting of several modalities, such as an episodic memory, is stored as a trace forming an associative structure in the cortico-cortical network.

Post-fear conditioning (Tone-light/light, foot shock)

Figure 4E shows the responses when Tone-light was applied and followed by Light-shock comprising aversive foot shock. Similar to Pre-fear conditioning, Post-fear conditioning (sensory preconditioning) induced not only a response in the main sensory response area, but also associative responses, besides the response of S2 and V1 to tone. This appeared as combined responses of other sensory areas, which were V1, LV, A1 (negative), and DC to foot shock (Fig. 4E, gray box in Fig. 5A), S1, S2, A1, and DC to light (Fig. 4E, gray box in Fig. 5B), and S1 and LV to tone (Fig. 4E, gray box in Fig. 5C). These results suggest that conditioning forms an association of cortical responses and plays an important role in memory storage in the cortico-cortical network. In addition, the associative responses in our results are considered to be the neuronal bases of the “associative chain explanation” in which CS1 (tone) → CS2 (light) → US (shock) (Gewirtz and Davis 2000).

Extinction and facilitation of associative cortico-cortical responses

In the associative response of the visual cortex V1 to foot shock as an aversion stimulation in Fig. 5A, the results of Pre-fear conditioning revealed that the associative response induced by Light-shock (light-gray box) was significantly reduced (P = 0.022) by the subsequent Tone-light (hatched box). This is considered to indicate extinction of a memory trace (Bouton et al. 2006, Yokose et al. 2017). In contrast, the results of Post-fear conditioning showed that the mean associative response (gray box) was larger than the one produced by Light-shock. These results, corresponding to the increasing and decreasing freezing of animals during the second-order conditioning, are shown in Fig. 3B and D, respectively. The findings are considered to reflect a facilitation of reinforcement in memory trace in which the sensory preconditioning increased the associative response in V1 to foot shock, induced by the subsequent fear conditioning. There was a significant difference in the associative response between the two types of second-order conditioning (P = 0.015). However, no difference was found in the difference in LV. Interestingly, the mean response in A1, which was negatively induced by Light-shock (light-gray box), was reduced by Pre-fear conditioning (hatched box) and was still negatively boosted by Post-fear conditioning (gray box). This may correspond in the same way to that seen in V1, but on the opposite side, because the auditory cortex A1 is inhibited by somatosensory stimuli (Iurilli et al. 2012; Henschke et al. 2015), and the associative response was transferred from the visual area to the auditory area (Rizley and Rescorla 1972). We found that the associative response in A1 was consolidated with extinction or facilitation depending on the temporal sequence of the second-order conditioning.

Next, regarding the magnitude of the response to light after each conditioning (Fig. 5B), associative responses (negative and positive) were found in A1 for Tone-light, Pre-fear, and Post-fear conditioning. A visuo-auditory association has been reported even in the absence of US (Ogi et al. 2019). The positively increased associative responses in both Pre-fear and Post-fear conditioning meant that the visuo-auditory association was facilitated by the preceding or subsequent visuo-somatosensory association in Light-shock conditioning.

On the other hand, the response to light in V1 after Post-fear conditioning (gray box) was small compared with the other response in V1. There are two possible reasons for this situation. One is that the response in V1 was affected by the associative factor in A1, because Nishimura and Song (2012) reported that a visuo-auditory interaction whose initial site was V1 resulted in a negative auditory response in V1. The other is that the first-order fear conditioning has some factor that negatively affects the induction of the subsequent sensory conditioning. Moreover, given the magnitude of the response to tone after each type of conditioning in Fig. 5C, the response to tone in V1 was not appeared. On the other hand, the associative responses to tone in S1 was induced only after Post-fear conditioning. This suggests that there is an “associative chain explanation” (Gewirtz and Davis 2000) in which the light stimulus acts as an intermediary in the second-order conditioning and the sequence of the second-order conditioning comprising sensory preconditioning (Tone-light) is important. In addition, the associative response in LV at the next stage downstream of V1 was induced after all types of conditioning.

The response to each sensory stimulus appeared as the response of the sensory cortex processing its main modality in the naïve state. However, without any conditioning, there was a nonsignificant response in the A1 cortex but a significant response in DC to the light stimulus, which indicates that there is direct projection from the visual input to the auditory cortex, especially to DC, at some stage of the visual information processing. This result supports the visuo-auditory interaction in guinea pig reported by Nishimura and Song (2012) and Kubota et al. (2017). One crucial aspect of our study is that the associative responses in different modality areas to each sensory stimulus (V1, LV, A1, and DC to foot shock in Fig. 5A; S1, S2, A1, and DC to light in Fig. 5B; and S1, S2, V1, LV to tone in Fig. 5C) were induced by first- or second-order conditioning.

Results of our present study were similar to those of our previous study (Ide et al. 2012) and another report (Headley and Weinberger 2015) involving a fear condition using tone (CS) and foot shock as a fear stimulus in which the associative response for tone (CS) was induced in S1. Such an associative response was not induced when the acetylcholine in the network was blocked by atropine, an inhibitor of the cholinergic channel (Kilgard and Merzenich 1998; Weinberger and Bakin 1998; Ji and Suga 2003; Ide 2013) and a learning-dependent increase in acetylcholine release in the cortex was also reported (Acquas et al. 1996; Butt et al. 2009). These results suggest that the emotional cholinergic circuit was also slightly evoked by sensory stimulation comprising tone and light, inducing the associative response. It can be considered that the sensory conditioning also affects the cholinergic channel. Then, because the associative response in S1 was blocked by application of atropine, a cholinergic channel blocker, the induction of the associative response was spread to sensory cortices by foot shock, an aversive stimulus. Therefore, the spreading of acetylcholine by foot shock may be one of the important factors underlying the induction of the associative response in our study. Therefore, in a future study, we would like to perform a pharmacological experiment using atropine to investigate whether the mechanism is widespread.

While there are various references, including conditioning closer to natural conditions, that plasticity occurred in the auditory pathway already at the level of the cochlear nucleus. Brief exposure to sounds (30 s) was sufficient to induce Fos-like activity (Rouiller 1992; Carretta et al. 1999a, b) and behaviorally relevant auditory stimuli lasting 500 ms elicited plasticity along the entire ascending pathway (Carretta et al. 1999a, b). Early plasticity has been demonstrated at several levels in other models, too (Yin et al. 2008; Kapolowicz and Thompson 2020). Moreover, Villa, Abeles and Tetko provided evidence that spatiotemporal firing patterns occurred within the auditory thalamus of the cat, thus suggesting that encoding of complex auditory information is likely to be consolidated in a circuit that includes the thalamus (Villa and Abeles 1990; Tetko and Villa 2001). Therefore, in our results, it is considered that the magnitude of the consolidated response was determined through the plastic modulation in cascading connection originated from early stage of sensory systems, which was associatively induced depending on the application order of the sensory conditioning and fear conditioning.

Moreover, a significant difference was found between Pre-fear conditioning and Post-fear conditioning in V1 and A1 in the case of shock stimulation and in V1 in the case of light stimulation. These results suggest that extinction and facilitation as intercortical memory appear as plastic changes in the primitive sensory area, which is consistent with other reports (Bieszczad and Weinberger 2012; Headley and Weinberger 2015). However, the significant differences among conditionings in S2, LV, and DC were not shown. It was considered that these regions may have a higher-order sensory association than S1, A1, and V1. Our results suggest that bottom-up information from various sensory systems is consolidated as associative responses in each area in the cortical network. We believe that our findings are closely related to the crucial role played by associative ways during overlapping memory traces reported by Yokose et al. (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the graduate student program at Tamagawa University and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 21120006 and 19K12223 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acquas E, Wilson C, Fibiger HC. Conditioned and Unconditioned Stimuli Increase Frontal Cortical and Hippocampal Acetylcholine Release: Effects of Novelty, Habituation, and Fear. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3089–3096. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-03089.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakin JS, Weinberger NM. Classical conditioning induces CS-specific receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex of the guinea pig. Brain Res. 1990;536(1–2):271–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90035-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieszczad KM, Weinberger NM. Extinction reveals that primary sensory cortex predicts reinforcement outcome: Sensory cortical plasticity induced by extinction. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:598–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizley JK, King AJ. Visual influences on ferret auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2009;258(1–2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Westbrook RF, Corcoran KA, Maren S. Contextual and temporal modulation of extinction: behavioral and biological mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AE, Chavez CM, Flesher MM, et al. Association learning-dependent increases in acetylcholine release in the rat auditory cortex during auditory classical conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campi KL, Bales KL, Grunewald R, Krubitzer L. Connections of auditory and visual cortex in the prairie vole (microtus ochrogaster): evidence for multisensory processing in primary sensory areas. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:89–108. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappe C, Rouiller EM, Barone P. Multisensory anatomical pathways. Hear Res. 2009;258:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretta D et al. (1999a) c-Fos expression in the auditory pathways related to the significance of acoustic signals in rats performing a sensory-motor task. Brain Res. 841:170–183. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10546999/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carretta D et al. (1999b) Preferential induction of fos-like immunoreactivity in granule cells of the cochlear nucleus by acoustic stimulation in behaving rats. Neurosci Lett 259:123–126. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10025573/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Devonshire IM, Grandy TH, Dommett EJ, Greenfield SA. Effects of urethane anaesthesia on sensory processing in the rat barrel cortex revealed by combined optical imaging and electrophysiology: imaging and electrophysiology of barrel cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:786–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeline JM, Weinberger NM. Receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex during frequency discrimination training: selective retuning independent of task difficulty. Behavioral Neurosci. 1993 doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.107.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeline JM, Pham P, Weinberger NM. Rapid development of learning-induced receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107(4):539–551. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.107.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz JC, Davis M. Using pavlovian higher-order conditioning paradigms to investigate the neural substrates of emotional learning and memory. Learn Mem. 2000;7:257–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.35200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headley DB, Weinberger NM. Relational associative learning induces cross-modal plasticity in early visual cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:1306–1318. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstetter FJ, Fanselow MS. Differential second-order aversive conditioning using contextual stimuli. Anim Learn Behav. 1989;17:205–212. doi: 10.3758/BF03207636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henschke JU, Noesselt T, Scheich H, Budinger E. Possible anatomical pathways for short-latency multisensory integration processes in primary sensory cortices. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:955–977. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0694-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Conditioned stimulus as a determinant of the form of the Pavlovian conditioned response. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1977;3(1):77–104. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.3.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide Y, Miyazaki T, Lauwereyns J, et al. Optical imaging of plastic changes induced by fear conditioning in the auditory cortex. Cogn Neurodyn. 2012;6:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11571-011-9173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide Y, Takahashi M, Lauwereyns J, et al. Fear conditioning induces guinea pig auditory cortex activation by foot shock alone. Cogn Neurodyn. 2013;7:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s11571-012-9224-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iurilli G, Ghezzi D, Olcese U, Laasi G, Nazzaro C, Tonini R, Tucci V, Benfenati F, Medini P. Sound-driven synaptic inhibition in primary visual cortex. Neuron. 2012;73:814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Suga N. Tone-specific and nonspecific plasticity of the auditory cortex elicited by pseudoconditioning: role of acetylcholine receptors and the somatosensory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1384–1396. doi: 10.1152/jn.90340.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapolowicz MR and Thompson LT (2020) Plasticity in Limbic Regions at Early Time Points in Experimental Models of Tinnitus. Front Syst Neurosci 13:88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32038184/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kilgard MP, Merzenich MM. Cortical map reorganization enabled by nucleus basalis activity. Science. 1998;279:1714–1718. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayasi KI, suwa Y, Riquimaroux H, Audiovisual integration in the primary auditory cortex of an awake rodent. Neurosci Lett. 2013;534:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota M, Sugimoto S, Hosokawa Y, et al. Auditory-visual integration in fields of the auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2017;346:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay BPP, Westbrook RF, Glanzman DL, Holmes NM. Commonalities and differences in the substrates underlying consolidation of first- and second-order conditioned fear. J Neurosci. 2018;38(8):1926–1941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2966-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill RJ, Hasenstaub AR. Visual information present in infragranular layers of mouse auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2018;38:2854–2862. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3102-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata S, Takemoto M, Song W-J. Differential cortical and subcortical projection targets of subfields in the core region of mouse auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2020;386:107876. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2019.107876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M, Song W-J. Temporal sequence of visuo-auditory interaction in multiple areas of the guinea pig visual cortex. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogi M, Yamagishi T, Tsukano H, Nishio N, Hishida R, Takahashi K, Horii A, Shibuki K. Associative responses to visual shape stimuli in the mouse auditory cortex. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0223242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Furrow DR. Stimulus similarity as a determinant of pavlovian conditioning. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1977;3:203–215. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.3.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizley RC, Rescorla RA. Associations in second-order conditioning and sensory preconditioning. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1972;81:1–11. doi: 10.1037/h0033333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetko IV and Villa AE (2001) A pattern grouping algorithm for analysis of spatiotemporal patterns in neuronal spike trains. 2. Application to simultaneous single unit recordings. J Neurosci Methods 105: 15–24.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11166362/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Villa AE and Abeles M (1990) Evidence for spatiotemporal firing patterns within the auditory thalamus of the cat.Brain Res 509: 325–327.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2322827/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wallace MN, Rutkowski RG, Palmer AR. Identification and localisation of auditory areas in guinea pig cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2000;132:445–456. doi: 10.1007/s002210000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MT, Ramachandran R, Stein BE. A revised view of sensory cortical parcellation. PNAS. 2004;101:2167–2172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305697101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM, Bakin JS. Learning-induced physiological memory in adult primary auditory cortex: receptive field plasticity, model, and mechanisms. Audiol Neurotol. 1998;3:145–167. doi: 10.1159/000013787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P et al. (2008) Early stages of melody processing: stimulus-sequence and task-dependent neuronal activity in monkey auditory cortical fields A1 and R. J Neurophysiol 100: 3009–3029.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18842950/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yokose J, Okubo-Suzuki R, Nomoto M, Ohkawa N, Nishizono H, Suzuki A, Matsuo M, Tsujimura S, Takahashi Y, Nagase M, Watabe AM, Sasahara M, Kato F, Inokuchi K. Overlapping memory trace indispensable for linking, but not recalling, individual memories. Science. 2017;355:398–403. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]