Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the six-month impact of the advanced automated functions of a closed-loop control (CLC) system (Control-IQ) and a virtual educational camp (vEC) on emotions and time in range (TIR) of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Children and their parents participated in a three-day vEC. Clinical, glucose, and emotion data were evaluated before, just after, and six months after the vEC. Emotions were evaluated using adapted Plutchik's and Geneva Emotion Wheels.

Results

Forty-three children and adolescents (7–16 years) showed significant improvements in positive emotions immediately and six months after the vEC (67% and 65% vs 38%, p < 0.05, respectively), while mixed emotions were reduced (32% and 15% vs 61%, p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively). The median percentage TIR increased from 64% (IQR 54–72) to 75% (IQR 70–82) with Control-IQ (p < 0.001) six months after the vEC.

Conclusions

Positive emotions (joy, serenity, and satisfaction) significantly improved while mixed emotions were significantly worse six months after the initiation of a CLC system (Control-IQ) and a vEC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00592-022-01878-z.

Keywords: Emotions, Virtual educational camp, Advanced hybrid closed loop, Closed-loop control, Children, Adolescents, Type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Education maximizes the benefits of new diabetes technology. Educational camps, even if run virtually, represent a solid educational and emotional experience for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (1). Since negative emotions such as anger, frustration, hopelessness, fear, guilt, and shame are very common in people with diabetes, it is important to evaluate the impact of education on participants’ emotions. It is well known that emotions, especially negative emotions, can influence glucose trends in everyday life. Moreover, the literature describes diabetes distress as an affective condition associated with an individual’s frustrations, worries, and concerns about living with diabetes. This state is linked with fewer self-care behaviors, non-optimal glycemic control, and lower quality of life in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Improving diabetes management is therefore an important component of mitigating against these negative feelings and emotions (2,3). Defining and comprehensively measuring emotions can be challenging, but camps nevertheless represent an important setting for developing social and emotional learning skills (3).

While no study has evaluated the effects of technology on emotions during or after an educational camp, the psychological impact of technology on children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their parents has been evaluated (4–7). Indeed, insulin pumps led to improvements in diabetes-specific emotional distress (8, 9).

Given that children in particular can find it difficult to describe feelings, emotions can be associated with colors in children and in front of a computer screen (10). We previously evaluated the effectiveness of a closed-loop control (CLC) system with the Control-IQ algorithm (1). Building on this study, here we aimed of to evaluate, using colors, the emotional impact of a virtual educational camp (vEC) in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes using a CLC system with Control-IQ over six months of follow-up. As a secondary outcome, we also evaluated glycemic metrics six months after the vEC.

Methods

Nineteen Italian pediatric diabetes centers participated in this prospective, multicenter clinical study, as previously described (1). The study was approved by the coordinating center Ethical Committee (ASST Cremona) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was signed by each participants’ parents.

With the aim of strengthening educational support for children and their families using a CLC system (Tandem t:slim X2 (San Diego, CA) with the Control-IQ algorithm), a three-day vEC was organized from 6 to 8 November 2020, 13–30 days after users had upgraded from Basal-IQ to Control-IQ (1). Children (6–17 years of age) who had already used the Basal-IQ system for at least three months with the carbohydrate counting system and who were available to test Control-IQ technology and share their data via a data-syncing software (Diasend platform) were enrolled (1). None of the participants had cognitive deficits, affective disorders (depression, anxiety) or psychiatric diseases or were using psychiatric drugs. None had micro- or macrovascular complications. Participants, their parents, and diabetes teams from each center participated via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc., San Jose, CA). Using the online platform, the children and their parents participated in a series of activities, either exercising with the guidance of expert personal trainers, or informative (carbohydrate counting, diabetes management during exercise, fine tuning of Control-IQ algorithm), lasting about six hours per day. Various sessions were held by pediatric endocrinologists, expert in diabetes, dieticians, and psychologists. Details of the vEC structure and activities are reported in our previous publication (1). A psychologist (CP) asked each participant to describe their emotions at the end of each day according to the three primary colors. Emotions were subsequently evaluated using Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions and the Geneva Emotion Wheel (12–13) (Supplemental Figs. 1 and 2).

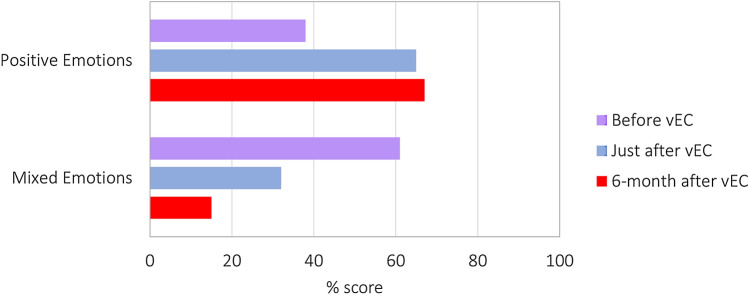

Fig. 1.

Frequency of positive and mixed emotions evaluated after upgrading the CLC from the Basal-IQ to Control-IQ algorithm, before vEC, just after the vEC, and six months after the vEC. No children expressed all negative emotions only

Emotions were evaluated before the vEC, at the end of the camp, and after six months. Participants associated emotion concepts with colors using the provided matching card containing ten standardized emotions/colors (Supplemental Fig. 3) according to Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions and the Geneva Emotion Wheel. The feelings of joy, serenity, amazement, and satisfaction were categorized as positive, the others as negative. A mixture of positive and negative feelings was called mixed emotions. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)-derived glucometrics were also evaluated.

The primary outcome was changes in emotions at the end of the vEC and after six months; while secondary outcomes included the percentage of time spent in the target range of 70 to 180 mg/dL (TIR) after six months; the percentage of time in which glucose values were < 54 mg/dL, 54–70 mg/dL, 180–250 mg/dL, or > 250 mg/dL; the coefficient of variation (%CV); and severe adverse events (severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis episodes).

The statistical analysis is detailed elsewhere (1). The frequency of different emotions at each timepoint was calculated; the comparison of general emotions and differences between positive, negative, and mixed emotions were analyzed with Fisher’s exact tests. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The 43 participants were aged 7 to 16 years (median 12, interquartile range (IQR) 9–13), of whom 53.5% were female. The duration of diabetes ranged from 2 to 13 years (median 6; IQR 4–9). The median BMI z-score was − 0.2 (IQR -0.6–0.2), and 19 (45%) participants were pre-pubertal according to Tanner’s classification.

Before camp, the most frequently reported feelings were joy (75.9%), serenity (65.5%), satisfaction (27.6%), fear (27.6%), amazement (24.1%), indifference (17.2%), and anger (17.3%). Just after the vEC, participants reported increases in joy (76.9%, + 1%), serenity (76.9%, + 11.4%), amazement (26.9%, + 2.8%) and reductions in fear (11.5%, − 16.1%), indifference (7.7%, − 9.5%), and anger (3.8%, -9.5%), although these changes were not significant (Table 1). After six months, amazement (− 24,1%, p < 0.05) and sadness (− 6,9%, p < 0.05) were significantly reduced compared to baseline (Fig. 1). Merging positive, negative, or mixed emotions, positive emotions increased either just after or six months after the vEC (67% and 65% vs 38%, both p < 0.05), while mixed feelings decreased (32% and 15% vs 61%, p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 1). Negative emotions alone were never present either before or after the camp. The median percentage TIR increased from 64% (IQR 54–72) to 75% (IQR 70–82) with Control-IQ (p < 0.001) after six months. Other glucometrics are shown in Table 2. No severe adverse events (severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis) were reported during the observation period.

Table 1.

Frequency of the emotions described using a modified Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions and the Geneva Emotion Wheel, just before, at the end, and six months after the virtual Educational Camp (vEC)

| Baseline (%) | After vEC (%) | Six months after vEC (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anger | 17.3 | 3.8 | 2.7 |

| Joy | 75.9 | 76.9 | 77.6 |

| Fear | 27.6 | 11.5 | 5.3 |

| Calm | 65.5 | 76.9 | 77.1 |

| Envy | 7.3% | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Surprise | 24.1 | 26.9 | 25.8 |

| Sadness | 6.5% | 6.9 | 5.1 |

| Indifference | 17.2 | 7.7 | 3.8 |

| Satisfaction | 27.6 | 29.9 | 29.4 |

| Disgust | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

Overall continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) outcomes measured before updating to the Control-IQ system and six months after the virtual Educational Camp (vEC)

| Baseline* | After 6 months* | Difference# | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Time < 54 mg/dl | 0 (0; 1) | 0 (0; 1) | 0 (− 1; 1) | 0.588 |

| % Time 54–70 mg/dl | 1 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 3) | 1 (− 1; 1) | 0.334 |

| % Time 70–180 mg/dl | 64 (54; 72) | 75 (70; 82) | 11 (9; 14) | < 0.001 |

| % Time 180–250 mg/dl | 26 (20; 28) | 18 (13; 22) | − 8 (− 7; − 4) | < 0.001 |

| % Time > 250 mg/dl | 8 (4; 15) | 3 (2; 6) | − 5 (− 6; − 3) | < 0.001 |

| % CGM active | 96 (88; 98) | 97 (92; 98) | 1 (− 1; 3) | 0.673 |

| Mean BG | 162 (145; 176) | 147 (135; 157) | − 15 (− 19; − 9) | < 0.001 |

| %CV | 36 (33; 38) | 32 (30; 36) | − 4 (− 6; − 2) | 0.001 |

| GMI | 7.2 (6.8; 7.5) | 6.8 (6.5; 7.1) | − 0.4 (− 0.5; − 0.2) | 0.001 |

*Values are presented as median (IQR)

#Differences are baseline vs. after 6-month values and presented as median (95% CI)

CGM outcome p values refer to the Wilcoxon signed–rank test; BG, blood glucose; CV, coefficient of variation; GMI, glucose management indicator

Discussion

In this daily-life study of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes, participants spent 75% of the time in the target range of 70–180 mg/dl after six months, 11% higher than before using a CLC system and participating in an vEC, confirming the data reported after three months (1) and representing the highest reported percentage TIR in this age group of patients with diabetes.

Similarly, the increase in positive emotions observed at the end of the vEC was confirmed after six months, highlighting the importance of the insulin delivery system used and its efficacy and safety for patient wellbeing.

There is some evidence that educational camps are beneficial to young people with type 1 diabetes. Sharing fun experiences and removing the isolation of living with diabetes contributes to positive emotions over time (14). It is interesting to note that even though our camp was run virtually (due to COVID-19 constraints), the possibility to share similar experiences—even if only over the internet—helped our patients to improve their positive emotions. This improvement has now been confirmed six months after the end of the vEC. Likewise, the use of an innovative technology (CLC system with Control-IQ algorithm) with favorable efficacy and safety (1) helps to positively influence the patient's mood, as recently described (15).

Evaluating emotions can be challenging, since many factors or circumstances can hypothetically influence them; however, the measures used have focus on specific emotions. Both before the vEC and at follow-up, each child and adolescent was assisted by the same psychologist (CP) to ensure consistency in their answering and approach.

Many studies have focused on mild cognitive deficits and affective disorders such as depression and anxiety in youths and adults with type 1 diabetes (16), but few or none have investigated their emotions. The patients enrolled in the present study did not have any psychiatric disorders, nor were they using psychiatric drugs, which would in any way affect either their emotions or the use of a new technology. Using an effective tool to manage diabetes and glycemic control appears to help children develop more positive emotions like joy, calmness, and satisfaction and decrease negative emotions like anger and fear. The negative feelings reported before the vEC may well have been linked to the anxiety that precedes the start of a new experience, and the positive emotions may be due to the positive effect of sharing experiences and best practices in the vEC. However, the positive effect persisted for six months, suggesting a more fundamental effect of the vEC beyond the experience alone.

Similar positive effects of technology have been reported (6–9), helping children to better accept technology (6) and reduce management distress (8). Diabetes technology is now an integral part of the lives of children with type 1 diabetes. However, children's experiences with these technologies are often overlooked. A recent study found that diabetes technologies prompted children and their parents to use data in daily care and that technologies could be liberating but also result in excess control (17). Diabetes can be stressful and demanding, but if the outcome (good glycemic control) exceeds expectations, even a demanding device can be accepted (18–20). We found that good TIR results were associated with improvements in emotional well-being. Giving the right space to the emotional experiences of children involved probably allowed them to access the fullness of the proposed experience and underscored its significance.

The lack of a control group was a limitation, making it difficult to interpret the contribution of the vEC intervention to the overall effect. However, encouragingly, the TIR was consistently above the recommended target in three-quarters of the sample and was maintained over the entire study period, as were improvements in positive emotions. Furthermore, alarms can be intrusive, but our patients all used the previous algorithm (Basal-IQ) before upgrading to Control-IQ and were used to alarms, so we do not believe that alarms significantly impacted our results. The study was strengthened by its multicenter design.

In conclusion, an educational camp organized to improve knowledge and use of an CLC system – even though it was virtual—not only significantly and persistently improved TIR in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes but also their positive emotions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author (AES), IR, and SS had full access to the data, and the corresponding author made the final decision to submit for publication. We would like to thank our patients with type 1 diabetes and their families who participated in the study. vEC Study Group collaborators: Marta Bassi, Genova, Riccardo Bonfanti, Milano, Patrizia Bruzzi, Modena, Maurizio Delvecchio, Bari, Sara Giorda, Torino, Dario Iafusco, Napoli, Giuseppina Salzano, Messina, Claudio Maffeis, Verona, Francesca Chiara Redaelli, Milano, Monica Marino, Ancona, Barbara Piccini, Firenze, Maria Rossella Ricciardi, Cagliari, Francesco Maria Rosanio, Napoli, Valentina Tiberi, Ancona, Michela Trada, Torino, Sara Zanetta, Novara, Stefano Zucchini, Bologna, Michela Calandretti, Torino, Federico Abate Daga, Torino, Rosaria Gesuita, Ancona, Claudio Cavalli, Cremona.

Author contribution

IR, VC, MM, RS, AR, ST, and AES conceived the study and drafted the virtual educational camp. IR, SS and AES drafted the report. CP and CC lead the psychology sessions and CP evaluated the emotions. MGB, DL, GM, CM, NM, EM, EP, BP, CR, GS, DT, and AZ collected data and supervised activities during the virtual educational camp. SS managed the data and performed the statistical analysis. IR and AES wrote the final version of the report. All authors and contributors collaborated in the interpretation of the results and discussing and revising the report.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not openly available as they were derived from data and collected by the vEC Study Group. They can be made available upon reasonable request to co-authors Ivana Rabbone and Andrea E Scaramuzza, coordinators of the study group.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

IR serves on the advisory board for Sanofi Aventis and Movi and has spoken for Aboca, Abbott, Sanofi Aventis and Eli Lilly. VC serves on the advisory board for Insulet and Eli Lilly, and his institution has received research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Dompè. DL has spoken for Abbott and has received support for attending meeting from Eli Lilly. AR has spoken for Menarini and Eli Lilly and has received support for attending meeting from Abbott. MM serves on the advisory board for Medtronic and Movi, has received support for attending meeting from Movi and has spoken for Abbott and Roche. EP serves on the advisory board for Medtronic and has received support for attending meeting from Movi. BP serves on the advisory board for Eli Lilly, has received support for attending meeting from Movi, Eli Lilly, Roche, and Ferring and has spoken for Sandoz. CR serves on the advisory board for Eli Lilly and has received support for attending meeting from Novo Nordisk. RS has spoken for Abbott and Lilly, has received support for attending meeting from Medtronic and Movi, and has served on advisory boards for Abbott and Sanofi. ST has spoken for Eli Lilly, Abbott, and Sanofi Aventis and serves on the advisory board for Movi. AES has spoken for Sanofi and Abbott, has received support for attending meeting from Movi and has served on the advisory board for Medtronic and Movi. CM has served on the advisory board for Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Aventis, and Abbott and has spoken for Aboca, Eli Lilly, Theras, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Aventis, and AMryt. RB has served on the advisory board for NovoNordisk, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Abbott, Medtronic, Movi, Roche, and Ypsomed and has received support for attending a meeting from Movi and has spoken for Eli Lilly, Abbott, and Sanofi Aventis. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the coordinating center Ethical Committee (ASST Cremona) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate and/or Consent to publish

Informed consent was signed by each participants’ parents.

Footnotes

See Acknowledgements section for full list of vEC Study Group.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ivana Rabbone and Silvia Savastio have contributed equally to the study.

Change history

7/26/2022

“List of collaborators name moved to acknowledgements”.

Contributor Information

Andrea Enzo Scaramuzza, Email: a.scaramuzza@gmail.com.

vEC Study Group:

Marta BassiBassi, Riccardo Bonfanti, Patrizia Bruzzi, Maurizio Delvecchio, Sara Giorda, Dario Iafusco, Giuseppina Salzano, Claudio Maffeis, Francesca Chiara Redaelli, Monica Marino, Barbara Piccini, Maria Rossella Ricciardi, Francesco Maria Rosanio, Valentina Tiberi, Michela Trada, Sara Zanetta, Stefano Zucchini, Michela Calandretti, Federico Abate Daga, Rosaria Gesuita, and Claudio Cavalli

References

- 1.Cherubini V, Rabbone I, Berioli MG, et al. Effectiveness of a closed-loop control system and a virtual educational camp for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a prospective, multicentre, real-life study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021 doi: 10.1111/dom.14491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg DM, Anderson BJ, de Wit M, Hilliard ME. Positive well-being in youth with type 1 diabetes during early adolescence. J Early Adolesc. 2018;38:1215–1235. doi: 10.1177/0272431617692444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iturralde E, Rausch JR, Weissberg-Benchell J, Hood KK. Diabetes-related emotional distress over time. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20183011. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richmond D, Sibthorp J, Wilson C. Understanding the role of summer camps in the learning landscape: an exploratory sequential study. J Youth Develop. 2021;14:9–30. doi: 10.5195/jyd.2019.780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franceschi R, Micheli F, Mozzillo E, et al. Intermittently scanned and continuous glucose monitor systems: a systematic review on psychological outcomes in pediatric patients. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:660173. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.660173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knox ECL, Quirk H, Glazebrook C, Randell T, Blake H. Impact of technology-based interventions for children and young people with type 1 diabetes on key diabetes self-management behaviours and prerequisites: a systematic review. BMC Endocr Disord. 2019;19:7. doi: 10.1186/s12902-018-0331-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forlenza GP, Messer LH, Berget C, Wadwa RP, Driscoll KA. Biopsychosocial factors associated with satisfaction and sustained use of artificial pancreas technology and its components: a call to the technology field. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18:114. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1078-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams RN, Tanenbaum ML, Hanes SJ, et al. Psychosocial and human factors during a trial of a hybrid closed loop system for type 1 diabetes management. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20:648–653. doi: 10.1089/dia.2018.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vesco AT, Jedraszko AM, Garza KP, Weissberg-Benchell J. Continuous glucose monitoring associated with less diabetes-specific emotional distress and lower A1c among adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:792–799. doi: 10.1177/1932296818766381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oldham V, Mumford B, Lee D, Jones J, Das G. Impact of insulin pump therapy on key parameters of diabetes management and diabetes related emotional distress in the first 12 months. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;166:108281. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonauskaite D, Abu-Akel A, Dael N, et al. Universal patterns in color-emotion associations are further shaped by linguistic and geographic proximity. Psychol Sci. 2020;31:1245–1260. doi: 10.1177/0956797620948810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plutchik R. The nature of emotions: human emotions have deep evolutionary roots, a fact that may explain their complexity and provide tools for clinical practice. Am Sci. 2001;89(4):344–350. doi: 10.1511/2001.4.344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scherer KR. What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Soc Sci Inf. 2005;44:695–729. doi: 10.1177/0539018405058216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonauskaite D, Parraga CA, Quiblier M, Mohr C. Feeling blue or seeing red? Similar patterns of emotion associations with colour patches and colour terms. Iperception. 2020;11(1):2041669520902484. doi: 10.1177/2041669520902484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fegan-Bohm K, Weissberg-Benchell J, DeSalvo D, Gunn S, Hilliard M. Camp for youth with type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:68. doi: 10.1007/s11892-016-0759-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinsker JE, Müller L, Constantin A, et al. Real-world patient-reported outcomes and glycemic results with initiation of Control-IQ technology. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23:120–127. doi: 10.1089/dia.2020.0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Duinkerken E, Snoek FJ, de Wit M. The cognitive and psychological effects of living with type 1 diabetes: a narrative review. Diabetic Med. 2020;37:555–563. doi: 10.1111/dme.14216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pals RAS, Hviid P, Cleal B, Grabowski D. Demanding devices—Living with diabetes devices as a pre-teen. Soc Sci Med. 2021;286:114279. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Commissariat PV, Roethke LC, Finnegan JL, et al. Youth and parent preferences for an ideal AP system: It is all about reducing burden. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(7):1063–1070. doi: 10.1111/pedi.13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hood K, Laffel LM, Danne T, et al. Lived experience of advanced hybrid closed-loop versus hybrid closed loop: patient-reported outcomes and perspectives. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;12:857–861. doi: 10.1089/dia.2021.0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not openly available as they were derived from data and collected by the vEC Study Group. They can be made available upon reasonable request to co-authors Ivana Rabbone and Andrea E Scaramuzza, coordinators of the study group.