Abstract

Background

Little is known about parental coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine hesitancy in children with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD). This survey estimated the prevalence and predictive factors of vaccine hesitancy among parents of children with NDD.

Methods

A nationally representative cross-sectional survey was conducted from October 10 to 31, 2021. A structured vaccine hesitancy questionnaire was used to collect data from parents aged ≥ 18 years with children with NDD. In addition, individual face-to-face interviews were conducted at randomly selected places throughout Bangladesh. Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify the predictors of vaccine hesitancy.

Results

A total of 396 parents participated in the study. Of these, 169 (42.7%) parents were hesitant to vaccinate their children. Higher odds of vaccine hesitancy were found among parents who lived in the northern zone (AOR = 17.15, 95% CI = 5.86–50.09; p < 0.001), those who thought vaccines would not be safe and effective for Bangladeshi children (AOR = 3.22, 95% CI = 1.68–15.19; p < 0.001), those who were either not vaccinated or did not receive the COVID-19 vaccine themselves (AOR = 12.14, 95% CI = 8.48–17.36; p < 0.001), those who said that they or their family members had not tested positive for COVID-19 (AOR = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.07–4.25), and those who did not lose a family member to COVID-19 (AOR = 2.12, 95% CI = 1.03–4.61; p = 0.040). Furthermore, parents who were not likely to believe that their children or a family member could be infected with COVID-19 the following year (AOR = 4.99, 95% CI = 1.81–13.77; p < 0.001) and who were not concerned at all about their children or a family member being infected the following year (AOR = 2.34, 95% CI = 1.65–8.37; p = 0.043) had significantly higher odds of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence of vaccine hesitancy, policymakers, public health practitioners, and pediatricians can implement and support strategies to ensure that children with NDD and their caregivers and family members receive the COVID-19 vaccine to fight pandemic induced hazards.

Keywords: Bangladesh, COVID-19, Pediatrics, Neurodevelopmental disorders, Parental vaccine hesitancy

Background

Vaccine hesitancy has been declared as one of the top 10 global health threats by the World Health Organization in 2019 [1]. Vaccine hesitancy can be defined as a delay in refusal or acceptance of a vaccine during the availability of a vaccination service [2]. For children, parental vaccine hesitancy is a significant barrier to a smooth vaccination program for fighting vaccine-preventable diseases [3]. In addition, previous studies have suggested that parents of children with a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) have a significantly higher vaccine hesitancy than parents with neurotypical children [4, 5].

Many parents of a child with NDD believe that vaccines can negatively impact their child's disability conditions [6]. Research has further demonstrated that parents of a child with NDD are also vaccine-hesitant for their other healthy children [7]. Conversely, children with NDD and their families are significant victims of the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [8]. Despite the limitations of public health data, some evidence suggests that children with NDD might be disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 itself or the pandemic’s impact on receiving services. In addition, children with NDD often have medical conditions that contribute to a higher risk of severe COVID-19 disease [9].

Furthermore, NDD patients affected by COVID-19 can experience difficulties accessing required healthcare and possess other characteristics that increase their difficulties faced due to COVID-19. These include mobility limitation, direct supervision requirements, challenges practicing prophylactic measures, and communicating disease symptoms [9]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that COVID-19 incidence, hospitalization, ICU admission, and death are much higher among COVID-19 patients with NDD [10].

Previous studies have found a high prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents for their neurotypical children in several settings; this was a matter of great concern when discussing immunization of an optimum population percentage to gain community herd immunity for fighting the pandemic [11, 12]. In addition, existing literature suggested that the higher COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of a child with NDD would raise further concern worldwide [13].

In Bangladesh, the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out was initiated on January 27, 2021, for adults aged 18 years and above [14]. Vaccination among students aged 12–17 started on November 1, 2021 [15]. However, very little is known about the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the parents of children aged under 18. Furthermore, it is crucial to determine whether the higher prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among parents of a child with NDD is consistent with the COVID-19 vaccination program, considering the public health importance of widespread COVID-19 vaccination in Bangladesh and other parts of the world. In addition, it is vital to identify other factors associated with vaccine hesitancy in this population that could inform the design of targeted, preemptive vaccine interventions. With this in mind, our objectives were to (1) estimate the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy within a nationally representative sample of parents of children with NDD and (2) identify the predictors of vaccine hesitancy considering socioeconomic and behavioral factors and COVID-19 threat perception.

Methods

Study design and participants

Anonymous data were collected from October 10 to 31, 2021, for this nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Individuals aged ≥ 18 years who were parents of at least one child aged under 18 years with neurodevelopmental disorders were eligible for this study. Individualized interviews using a structured questionnaire were conducted in homes and health care centers. Parents aged < 18 years were excluded from the study. A margin of 5% error, a confidence level of 95%, and a response distribution of 50% were used to calculate the sample size to target fathers/mothers of approximately 8 million children and secure a minimum sample size of 384 participants [16, 17]. Data were collected from 408 individuals.

Sampling technique

Data were collected from all eight divisions in Bangladesh. We identified approximately 150 government and non-government centers dealing with children with NDD. In addition, we visited 38 randomly selected centers to collect data of the parents. Approximately 450 parents were conveniently approached for the interviews.

The questionnaire

Previously employed vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 threat perception questionnaire modified for parents were used in this study [14]. In the first part, parents were asked about the likelihood of vaccinating their children with NDD. Vaccine hesitancy was measured using the question, “If a vaccine that would be effective against coronavirus among children was available, how likely are you to get your children with NDD vaccinated?” The response options for this question were “very likely,” “somewhat likely,” “not likely,” and “definitely not.” Participants were also asked two questions regarding the perceived COVID-19 threat: (1) “How likely is it that your children or a family member could get infected with coronavirus in the next one year?” The response options for this were “very likely,” “somewhat likely,” “not likely,” and “definitely not.” (2) “How concerned are you that your children or a family member could get infected with COVID-19 in the next year?” Here, response options were “very concerned,” “concerned,” “slightly concerned,” and “not concerned at all.” The second part of the questionnaire included a wide range of sociodemographic, behavioral, and COVID-19-related questions regarding both the child and parent.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to elaborate on the demographic characteristics of the study participants. Χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate vaccine hesitancy proportions and draw comparisons between subgroups. Responses were compared for various sociodemographic characteristics by dichotomizing the variable as positive (“very likely” and “somewhat likely”) or a negative (“not likely” and “definitely not”) attitude toward the COVID-19 vaccine, indicating the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed with vaccine hesitancy as a dependent variable and sociodemographic characteristics and perceived COVID-19 threat as predictor variables for vaccine hesitancy to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). In this model, we included factors significantly associated with vaccine hesitancy in the descriptive analysis. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was employed to ensure that the models adequately fit the data. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. SPSS version 0.22.0 (IBM Corp., USA) was used for all data analyses.

Results

With a 90.7% response rate, 408 parents provided informed consent and data for this study. Seven parents refused to answer the entire question and were thus excluded. We also excluded five more data points for inconsistent answers to the questions. Finally, a total of 396 parents (60.4% men) aged 34.54 ± 6.56 years (mean ± standard deviation) included in the analysis. Of the children, 60.9% were male, and 40.2% were in the 0–4-year-old group. The highest number of parents (27.5%) were in the 31–35-year-old group. Overall, 87.4% of parents were Muslim, 70.7% were belonged to nuclear family members, 44.2% had two children, 29.8% had a low education level, 24.2% were service holders, and 33.1% had a high household income. Among all participants, 49.2% were from the village, 62.6% lived in the central zone, including Dhaka, 76.3% were not tobacco users, 76.8% were regular religious practitioners, and 37.9% were politically neutral respondents. However, 3.3% of parents did not adhere to the standard government vaccination (other than COVID-19) programs, and 53.5% remained skeptical about COVID-19 vaccine safety and effectiveness for Bangladeshi children. Furthermore, 20.5% of parents were either not vaccinated or did not receive the COVID-19 vaccine themselves, but 39.6% of parents reported that they or their family members had tested positive for COVID-19 earlier, and 8.6% had lost a loved one due to COVID-19. Details of the responses to the questions regarding the likelihood of children or family members’ COVID-19 infection and the level of concern about children or family members being infected in the next year are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis: sociodemographic characteristics, COVID-19 threat, and parental vaccine hesitancy

| Variables | Total sample n (%) | Likelihood of vaccinating children | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not likely/definitely not n (%) | Very likely/somewhat-likely n (%) | |||

| All participants | 396 (100) | 169 (42.7) | 227 (57.3) | N/A |

| Children’s age group (in year) | ||||

| 0–4 | 159 (40.2) | 92 (57.9) | 67 (42.1) | < 0.001 |

| 5–9 | 156(39.4) | 60 (38.5) | 96 (61.5) | |

| 10–14 | 63 (15.9) | 13 (20.6) | 50 (79.4) | |

| 15–17 | 18 (4.5) | 4 (22.2) | 14 (77.8) | |

| Children’s gender | ||||

| Male | 241 (60.9) | 104 (43.2) | 137 (56.8) | 0.811 |

| Female | 155 (39.1) | 65 (41.9) | 90 (58.1) | |

| Parents’ age group (in year) | ||||

| 18–25 | 27 (6.8) | 13 (48.1) | 14 (51.9) | < 0.001 |

| 26–30 | 94 (23.7) | 49 (52.1) | 45 (47.9) | |

| 31–35 | 109 (27.5) | 57 (52.3) | 52 (47.7) | |

| 36–40 | 101 (25.5) | 36 (35.6) | 65 (64.4) | |

| 41–45 | 45 (11.4) | 14 (31.1) | 31 (68.9) | |

| 46–50 | 15 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | |

| ≥ 51 | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | |

| Parents’ gender | ||||

| Female | 157 (39.6) | 74 (47.1) | 83 (52.9) | 0.146 |

| Male | 239 (60.4) | 95 (39.7) | 144 (60.3) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 376 (94.9) | 163 (43.4) | 213 (56.6) | 0.239 |

| Divorced or widow | 20 (5.1) | 6 (30) | 14 (70) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Muslim | 346 (87.4) | 149 (43.1) | 197 (56.9) | 0.521 |

| Hindu | 47 (11.9) | 20 (42.6) | 27 (57.4) | |

| Buddha | 1 (.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | |

| Cristian | 2 (.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | |

| Type of family | ||||

| Joint family | 116 (29.3) | 56 (48.3) | 60 (51.7) | 0.147 |

| Nuclear family | 280 (70.7) | 113 (40.4) | 167 (59.6) | |

| Number of children | ||||

| One | 131 (33.1) | 66 (50.4) | 65 (49.6) | 0.090 |

| Two | 175 (44.2) | 67 (38.3) | 108 (61.7) | |

| Three or more | 90 (22.7) | 36 (40) | 54 (60) | |

| Educational qualification | ||||

| ≤ High school | 118 (29.8) | 46 (39) | 72 (61) | 0.176 |

| College education | 99 (25) | 44 (44.4) | 55 (55.6) | |

| Graduate | 103 (26) | 52 (50.5) | 51 (49.5) | |

| Post graduate | 76 (19.2) | 27 (35.5) | 49 (64.5) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Service | 96 (24.2) | 41 (42.7) | 55 (57.3) | 0.419 |

| Business | 60 (15.2) | 32 (53.3) | 28 (46.7) | |

| Unemployed | 21 (5.3) | 10 (47.6) | 11 (52.4) | |

| Student | 6 (1.5) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Home maker | 157 (39.6) | 65 (41.4) | 92 (58.6) | |

| Healthcare | 26 (6.6) | 7 (26.9) | 19 (73.1) | |

| Daily labor | 30 (7.6) | 12 (40) | 18 (60) | |

| Monthly household income (৳) | ||||

| < ৳15 000 | 103 (26) | 45 (43.7) | 58 (56.3) | 0.973 |

| ৳ 15,000–30,000 | 86 (21.7) | 35 (40.7) | 51 (59.3) | |

| ৳ 31,000–45,000 | 76 (19.2) | 32 (42.1) | 44 (57.9) | |

| > ৳ 45,000 | 131 (33.1) | 57 (43.5) | 74 (56.5) | |

| Current residence type | ||||

| Own | 186 (47) | 81 (43.5) | 105 (56.5) | 0.907 |

| Rented | 190 (48) | 79 (41.6) | 111 (58.4) | |

| Others | 20 (5) | 9 (45) | 11 (55) | |

| Permanent address | ||||

| Village | 195 (49.2) | 88 (45.1) | 107 (54.9) | 0.128 |

| Semi city | 84 (21.2) | 40 (47.6) | 44 (52.4) | |

| City | 117 (29.5) | 41 (35) | 76 (65) | |

| Current living location | ||||

| Central zone | 248 (62.6) | 107 (43.1) | 141 (56.9) | < 0.001 |

| North zone | 74 (18.7) | 44 (59.5) | 30 (40.5) | |

| South zone | 74 (18.7) | 18 (24.3) | 56 (75.7) | |

| Present tobacco user | ||||

| No | 302 (76.3) | 127 (42.1) | 175 (57.9) | 0.653 |

| Yes | 94 (23.7) | 42 (44.7) | 52 (55.3) | |

| Regular religious practice | ||||

| No | 92 (23.2) | 39 (42.4) | 53 (57.6) | 0.950 |

| Yes | 304 (76.8) | 130 (42.8) | 174 (57.2) | |

| Political affiliation | ||||

| Ruling party | 126 (31.8) | 45 (35.7) | 81 (64.3) | 0.160 |

| Opposition | 49 (12.4) | 19 (38.8) | 30 (61.2) | |

| Neutral | 150 (37.9) | 73 (48.7) | 77 (51.3) | |

| Prefer not to say | 71 (17.9) | 32 (45.1) | 39 (54.9) | |

| Vaccinated/plan to vaccinate children under regular govt. vaccination programs (other than COVID-19) | ||||

| No | 13 (3.3) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 0.779 |

| Yes | 383 (96.7) | 163 (42.6) | 220 (57.4) | |

| Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine will be safe and effective for Bangladeshi children? | ||||

| No | 22 (5.6) | 19 (86.4) | 3 (13.6) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 162 (40.9) | 12 (7.4) | 150 (92.6) | |

| Skeptical | 212 (53.5) | 138 (65.1) | 74 (34.9) | |

| Have you taken or planned to take the COVID-19 vaccine? | ||||

| No | 81 (20.5) | 64 (79) | 17 (21) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 315 (79.5) | 105 (33.3) | 210 (66.7) | |

| Were you or your family member(s) tested positive for COVID-19? | ||||

| No | 239 (60.4) | 121 (50.6) | 118 (49.4) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 157 (39.6) | 48 (30.6) | 109 (69.4) | |

| Have you lost any of your family member(s) for COVID-19? | ||||

| No | 362 (91.4) | 163 (45) | 199 (55) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 34 (8.6) | 6 (17.6) | 28 (82.4) | |

| Perceived likelihood of children or family members’ infection in the next year | ||||

| Very likely | 56 (14.1) | 9 (16.1) | 47 (83.9) | < 0.001 |

| Somewhat likely | 240 (60.6) | 102 (42.5) | 138 (57.5) | |

| Not likely | 73 (18.4) | 40 (54.8) | 33 (45.2) | |

| Definitely not | 27 (6.8) | 18 (66.7) | 9 (33.3) | |

| Level of concern about children or family members’ infection in the next year | ||||

| Very concerned | 49 (12.4) | 14 (28.6) | 35 (71.4) | < 0.001 |

| Concerned | 128 (32.3) | 38 (29.7) | 90 (70.3) | |

| Slightly concerned | 122 (30.8) | 56 (45.9) | 66 (54.1) | |

| Not concerned at all | 97 (24.5) | 61 (62.9) | 36 (37.1) | |

Bold faces are significant at a 5% significance level

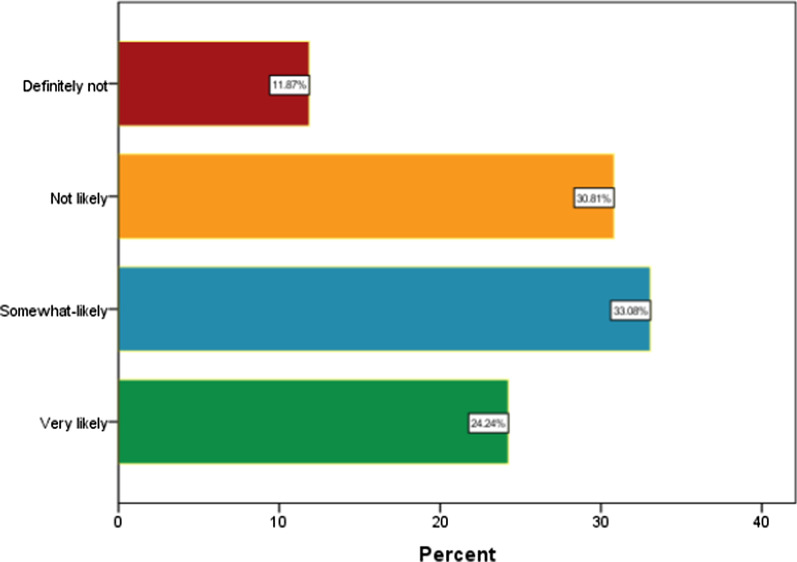

Overall, 42.7% (CI = 37.82–47.57) of parents were hesitant to vaccinate their children with NDD against COVID-19. Table 1 displays the result of descriptive analysis. The highest prevalence of vaccine hesitancy was observed among parents of children aged 0–4 years (57.9%; p < 0.001), parents aged 31–35 years (52.3%; p < 0.001), those living in the northern zone (59.5%; p < 0.001), those who did not believe the vaccine will be safe and effective for Bangladeshi children (86.4%; p < 0.001), those who were either not vaccinated or chose not receive the COVID-19 vaccination themselves (79%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, vaccine hesitancy was highest among parents who said that they or their family members had not tested positive for COVID-19 (50.6%; p < 0.001) and those who did not lose any family member due to COVID-19 (45%; p = 002). Moreover, participants who were not likely to believe that their children or a family member could be infected with COVID-19 the following year (66.7%; p < 0.001) and those who were not concerned at all about their children or a family member getting infected in the following year (62.9%; p < 0.001) showed high levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of vaccine acceptance or refusal. Table 2 displays the results of multiple logistic regression analyses. The subgroup of participants with the highest odds of vaccine hesitancy were those who lived in the northern zone (AOR = 17.15, 95% CI = 5.86–50.09; p < 0.001), who thought vaccines would not be safe and effective for Bangladeshi children (AOR = 3.22, 95% CI = 1.68–15.19; p < 0.001), who were either not vaccinated or did not receive the COVID-19 vaccine themselves (AOR = 12.14, 95% CI = 8.48–17.36; p < 0.001), who said that they or their family members had not tested positive for COVID-19 (AOR = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.07–4.25), and who did not lose a family member to COVID-19 (AOR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.07–4.61; p = 0.040). Furthermore, parents who were not likely to believe that their children or a family member could be infected with COVID-19 the following year (AOR = 4.99, 95% CI = 1.81–13.77; p < 0.001) and not concerned at all about their children or a family member getting infected the next year (AOR = 2.34, 95% CI = 1.65–8.37; p = 0.043) had significantly higher odds of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Fig. 1.

Likelihood of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/refusal by Bangladeshi parents for children with neurodevelopmental disorders

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression: predictors of parental vaccine hesitancy in study participants

| Variables | Adjusted OR | SE | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s age group (in year) | |||||

| 0–4 | 1.57 | 0.83 | 0.31 | 8.02 | 0.588 |

| 5–10 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 0.12 | 3.04 | 0.550 |

| 11–14 | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 2.23 | 0.304 |

| 15–< 18 | References | ||||

| Parents’ age group (in year) | |||||

| 18–25 | Reference | ||||

| 26–30 | 1.25 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 4.18 | 0.722 |

| 31–35 | 1.31 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 4.43 | 0.667 |

| 36–40 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 0.28 | 3.40 | 0.959 |

| 41–45 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.19 | 3.33 | 0.745 |

| ≥ 46 | 1.10 | 0.81 | 0.31 | 3.54 | 0.878 |

| Current living location | |||||

| Central zone including Dhaka | 7.25 | 0.45 | 2.98 | 17.67 | < 0.001 |

| North zone | 17.15 | 0.55 | 5.87 | 50.09 | < 0.001 |

| South zone | Reference | ||||

| Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine will be safe and effective for Bangladeshi children | |||||

| No | 3.22 | 0.79 | 1.68 | 15.19 | 0.049 |

| Yes | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.09 | < 0.001 |

| Skeptical | Reference | ||||

| Have you taken or plan to take the COVID-19 vaccine | |||||

| No | 12.14 | 0.18 | 8.48 | 17.36 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | Reference | ||||

| Were you or your family member(s) tested positive for COVID-19 | |||||

| No | 2.13 | 0.35 | 1.07 | 4.25 | 0.032 |

| Yes | Reference | ||||

| Have you lost any of your family member(s) for COVID-19 | |||||

| No | 2.19 | 0.38 | 1.04 | 4.62 | 0.040 |

| Yes | Reference | ||||

| Perceived likelihood of children or family members’ infection in the next year | |||||

| Very likely | Reference | ||||

| Somewhat likely | 4.54 | 0.52 | 0.99 | 22.36 | 0.051 |

| Not likely | 4.71 | 0.63 | 1.32 | 15.67 | 0.017 |

| Definitely not | 4.99 | 0.79 | 1.81 | 13.78 | 0.002 |

| Level of concern about children or family members’ infection in the next year | |||||

| Very concerned | Reference | ||||

| Concerned | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 2.16 | 0.527 |

| Slightly concerned | 1.04 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 3.21 | 0.943 |

| Not concerned at all | 2.34 | 0.65 | 1.65 | 8.37 | 0.043 |

Bold faces are significant at a 5% significance level

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in parents of children with NDD. This nationally representative survey found a significantly high prevalence of parental vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh. Logistic regression analysis suggested that location of residence, perception about vaccine safety and effectiveness for children, experience of family members being testing positive for COVID-19, and a family members’ death due to COVID-19 strongly predicted vaccine hesitancy. Furthermore, COVID-19 threat perceptions were significantly associated with parental vaccine hesitancy for their children with NDD.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is generally high among Bangladeshi adults [14]; however, we found a higher parental vaccine hesitancy among parents for their children with NDD in this study (32.5% vs. 42.7%). This prevalence was also much higher than that of common non-COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of children with NDD in another country [4]. Nonetheless, a contemporary study conducted in Taiwan among caregivers of children with attention–deficit/hyperactivity disorder found that 37% of caregivers hesitated or refused to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 [18]. In addition, 42% and 52% of parents of healthy children in the USA and China, respectively, were hesitant to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 [12, 19].

In line with the findings of previous studies [19, 20], we found higher vaccine hesitancy among younger parents as well as parents of younger children. The safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine in children aged < 12 years remains unclear, which might cause higher vaccine hesitancy among parents of young children [21]. However, more studies are warranted to understand what drives young parents not to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. Conversely, in agreement with our previous study on the adult population, we found remarkably higher vaccine hesitancy among parents who lived in the central and northern zones of Bangladesh [14]. However, it is impossible to infer the cause of higher vaccine hesitancy in these areas from our data, thus indicating the need for additional studies to understand causal relationships.

Our analyses found that one-fifth of the participants were either not vaccinated or chose not receive the COVID-19 vaccination themselves. Unsurprisingly, 80% of the non-vaccinated parents were hesitant to vaccinate their children. Previous studies have also observed a significant association between parental willingness to get vaccinated and reported intentions to vaccinate children [19, 21]. However, we found a lower prevalence of parental vaccine hesitancy for their children among participants who reported that their family members tested positive for or died of COVID-19. Therefore, it can be assumed that perception of disease threats drove these parents to make a favorable decision regarding vaccination.

Disease threat perception is the key to theories of many health behaviors. A systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the likelihood of risk, susceptibility, and severity from the disease is significantly associated with vaccine hesitancy [22]. Furthermore, a recent study revealed that high COVID-19 risk perception was associated with reduced vaccine hesitancy [23]. Another study suggested that reduced risk perception is associated with reduced COVID-19 vaccine uptake [24]. In agreement with these findings, our study found that perceived COVID-19 threat was one of the strongest predictors of parental vaccine hesitancy. In contrast, an empirical investigation revealed that, among others, the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine outweighs disease risk perception when predicting vaccine hesitancy [25]. Our study also found a high prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among parents who remained skeptical or did not perceive that the vaccine would be safe and effective for Bangladeshi children.

This study had several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of this study only portrays the community response at the time of the study. However, studies have found that vaccine hesitancy is complex in disposition and is adherence-specific, varying over time, location, and the perceived behavioral nature of the community [26–28]. Second, the inclusion of the Bangladeshi tribal population may help increase the generalizability of the findings. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to provide baseline evidence regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of children with NDD, identifying a range of subgroups of the parents that must be considered during widespread vaccination discussions in low- and middle-income countries. Finally, face-to-face data collection from randomly selected regions throughout Bangladesh would have reduced nonresponse bias and provided a better representation of the population in the sample, thus increasing the generalizability of the study.

Conclusions

Given the increased prevalence of underlying health conditions, suboptimal vaccination rates, and systemic inequities, children with NDD are likely to have a higher risk of being infected with COVID-19 and its outcomes. Policymakers, public health practitioners, and pediatricians should address the findings of this study when discussing and implementing strategies to ensure that children with NDD, their caregivers and family members, and service providers receive the COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, highlighting the unique considerations for COVID-19 vaccination for children with NDD can support equitable vaccination access for these children and their families.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the participants for providing the information used to conduct the study. We also thank Professor Dr. Ahmed Hossain, PhD (Biostatistics) for his help in data analysis and result interpretations.

Abbreviations

- NDD

Neurodevelopmental disorders

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease of 2019

Authors’ contributions

MA: conceived and designed the experiments; performed the experiments; analyzed and interpreted the data; contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data; wrote the paper. SA, ASB, A-sS, MdAI, TAU, TSP, ZT, and USK: performed the experiments; contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data; wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearances for this study were obtained from the institutional review board of Uttara Adhunik Medical College and Hospital. The voluntary nature of the interview was explained to the participants. All the participants have provided written informed consent. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines were strictly followed throughout the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Ali, Email: m180002@student.bup.edu.bd.

Tasnuva Shamarukh Proma, Email: physioproma@gmail.com.

Zarin Tasnim, Email: zarintasnim007@gmail.com.

Md. Ariful Islam, Email: arifanikphysio@gmail.com.

Tania Akter Urmi, Email: urmit49@gmail.com.

Sohel Ahmed, Email: ptsohel@gmail.com.

Abu-sufian Sarkar, Email: ptsufian21@gmail.com.

Atia Sharmin Bonna, Email: atiasharmin72@gmail.com.

Umme Salma Khan, Email: khan14ku@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Aranda S. Ten threats to global health in 2019 [Internet]. World Health Organisation (WHO). 2019; p. 1–18.

- 2.MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine [Internet]. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olusanya OA, Bednarczyk RA, Davis RL, Shaban-Nejad A. Addressing parental vaccine hesitancy and other barriers to childhood/adolescent vaccination uptake during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2021;12:855. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.663074/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonsu NEM, Mire SS, Sahni LC, Berry LN, Dowell LR, Minard CG, et al. Understanding vaccine hesitancy among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder and parents of children with non-autism developmental delays. J Child Neurol [Internet]. 2021;36(10):911–918. doi: 10.1177/08830738211000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerbo O, Modaressi S, Goddard K, Lewis E, Fireman BH, Daley MF, et al. Vaccination patterns in children after autism spectrum disorder diagnosis and in their younger siblings. JAMA Pediatr [Internet]. 2018;172(5):469. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goin-Kochel RP, Mire SS, Dempsey AG. Emergence of autism spectrum disorder in children from simplex families: relations to parental perceptions of etiology. J Autism Dev Disord [Internet]. 2015;45(5):1451–1463. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuwaik GA, Roberts W, Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson S, Smith IM, Szatmari P, et al. Immunization uptake in younger siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism [Internet]. 2014;18(2):148–155. doi: 10.1177/1362361312459111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzo R, Karlov L, Maugeri N, Di Silvestre S, Eapen V. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family wellbeing in the context of neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat [Internet]. 2021;17:3007–3014. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S327092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinker SC, Cogswell ME, Peacock G, Ryerson AB. Important considerations for COVID-19 vaccination of children with developmental disabilities. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2021;148(4):e2021053190. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleason J, Ross W, Fossi A, Blonsky H, Tobias J, Stephens M. The devastating impact of Covid-19 on individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2021;

- 11.Alfieri NL, Kusma JD, Heard-Garris N, Davis MM, Golbeck E, Barrera L, et al. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children: vulnerability in an urban hotspot. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021;21(1):1662. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11725-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang M-X, Lin X-Q, Chen Y, Tung T-H, Zhu J-S. Determinants of parental hesitancy to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in China. Expert Rev Vaccines [Internet]. 2021 doi: 10.1080/14760584.2021.1967147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aggarwal S, Madaan P, Sharma M. Vaccine hesitancy among parents of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: a possible threat to COVID-19 vaccine coverage. J Child Neurol [Internet]. 2021;13(10):088307382110421. doi: 10.1177/08830738211042133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali M, Hossain A. What is the extent of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh? A cross-sectional rapid national survey. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2021;11(8):e050303. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Ali M, Ahmed S, Bonna AS, Sarkar A, Islam MA, Urmi TA, et al. Parental coronavirus disease vaccine hesitancy for children in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. F1000Research [Internet]. 2022;11:90. 10.12688/f1000research.76181.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Taherdoost H. Determining sample size; How to calculate survey sample size. Int J Econ Manag Syst [Internet]. 2017;2(2):237–239. [Google Scholar]

- 17.James E, Joe W, Chadwick C. Organizational research: determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf Technol Learn Perform J. 2001;19(1):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CS, Hsiao RC, Chen YM, Yen CF. Factors related to caregiver intentions to vaccinate their children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder against covid-19 in Taiwan. Vaccines [Internet]. 2021;9(9):983. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szilagyi PG, Shah MD, Delgado JR, Thomas K, Vizueta N, Cui Y, et al. Parents’ intentions and perceptions about COVID-19 Vaccination for their children: results from a national survey. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2021;148(4):e2021052335. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yılmaz M, Sahin MK. Parents’ willingness and attitudes concerning the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract [Internet]. 2021;75(9):e14364. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teasdale CA, Borrell LN, Shen Y, Kimball S, Rinke ML, Fleary SA, et al. Parental plans to vaccinate children for COVID-19 in New York city. Vaccine [Internet]. 2021;39(36):5082–5086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Heal Psychol [Internet]. 2007;26(2):136–145. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caserotti M, Girardi P, Rubaltelli E, Tasso A, Lotto L, Gavaruzzi T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2021;272:113688. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kucukkarapinar M, Karadag F, Budakoglu I, Aslan S, Ucar O, Yay A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its relationship with illness risk perceptions, affect, worry, and public trust: an online serial cross-sectional survey from Turkey. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol [Internet]. 2021;31(1):98–109. doi: 10.5152/pcp.2021.21017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlsson LC, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Nolvi S, et al. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: the case of COVID-19. Pers Individ Dif [Internet]. 2021;172:110590. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao X, Wong RM. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: a meta-analysis. Vaccine [Internet]. 2020;38(33):5131–5138. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson K, Nguyen HH, Brehaut H. Acceptance of a pandemic influenza vaccine: a systematic review of surveys of the general public. Infect Drug Resist [Internet]. 2011;4(1):197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S23174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.