Abstract

The identification of theoretically and empirically supported correlates of suicide ideation is important to improve treatment approaches to suicide. This study sought to examine the association between interpersonal trust (theoretically conceptualized as a distal risk marker) and suicide ideation in adolescence. Specifically, it was hypothesized that interpersonal trust would be negatively associated with suicide ideation via perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (conceptualized as more proximal risk markers). Data were drawn from a cross-sectional sample of 387 adolescent inpatients between the ages of 12 and 17 years (M = 14.72, SD = 1.49). The sample was 63.6% female, 37.5% Hispanic, 26.9% African American/Black, and 25.8% Caucasian. Adolescents completed a series of self-report measures to assess thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, interpersonal trust, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation. A structural equation model was fit to the data, and results demonstrated a significant indirect path from interpersonal trust to suicide ideation via perceived burdensomeness, but not thwarted belongingness. Results suggest that interpersonal trust may be a distal risk marker for suicide ideation and that interventions to increase interpersonal trust may help prevent the development of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicide ideation.

Data from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System indicate that 17.7% of high school students report having seriously considered suicide in the past 12 months and that 8.6% report having made a suicide attempt over the same period (Kann et al., 2016). One recent estimate places the economic impact of suicide and suicide attempts among 15 to 24 year olds at over $15.5 billion in 2013 alone (Shepherd, Gurewich, Lwin, Reed, & Silverman, 2016). For these reasons, efforts are being made to detect or prevent suicide ideation early, before it results in suicide attempts or suicide. To facilitate these efforts to move suicide prevention “upstream,” additional attention must be paid to identifying distal markers of suicide risk that may serve as targets for preventive intervention.

The interpersonal–psychological theory of suicide (IPTS; Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) has received considerable empirical support among adolescent samples (e.g., Hill & Pettit, 2014; Stewart, Eaddy, Horton, Hughes, & Kennard, 2015) and provides a framework for conceptualizing and organizing correlates of suicide risk. The IPTS proposes that suicide ideation results from the presence of perceived burdensomeness, conceptualized as the belief that one has become a burden or drain on the resources of others, and thwarted belongingness, comprised of a sense of loneliness and perceived lack of reciprocal care (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). According to the IPTS, perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness act as proximal risk factors through which other, more distal risk markers exert their influence on suicide ideation. Recent data support this position, as perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness mediate the association between risk markers such as stress, relatedness, competence, and autonomy and suicide ideation (Buitron et al., 2016; Hill & Pettit, 2013; Tucker & Wingate, 2014). Given the proximal nature of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, identifying other factors associated with these IPTS constructs may provide additional targets for interventions to prevent suicide ideation.

THE ROLE OF INTERPERSONAL TRUST

One potential factor in this regard is interpersonal trust. Major developmental theories such as Bowlby’s (1969) attachment theory and Erikson’s (1963) psychosocial stages espouse the idea that developing interpersonal trust early in life is crucial to later adaptive psychosocial functioning (Simpson, 2007a). Interpersonal trust is therefore conceptualized as a distal factor that may influence current psychosocial functioning. Empirical research also supports this idea: trust early in life has been prospectively linked with later psychosocial functioning in adolescents (Malti, Averdijk, Ribeaud, Rotenberg, & Eisner, 2013); cross-sectionally, interpersonal trust has been positively associated with healthy relationships (Simpson, 2007b), academic achievement, and social competence (Wentzel, 1991), and negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Lester & Gatto, 1990). Rotenberg et al. (2005) proposed that trust beliefs comprise three bases: reliability, emotional trust, and honesty. Reliability refers to the belief that others will “keep their word,” emotional trust refers to the belief that others will refrain from causing emotional harm (e.g., by keeping confidentiality), and honesty refers to the belief that others will tell the truth and act with benevolent intent (Rotenberg et al., 2005). Research utilizing this interpersonal trust framework indicates that maladaptive interpersonal trust beliefs are associated with lower peer acceptance and greater aggression, social nonengagement, peer rejection, loneliness, depressive symptoms, and anxiety (Rotenberg et al., 2014). This is particularly relevant for adolescents as longitudinal studies have shown that maladaptive attachment relationships in infancy lead to particular risk for social maladaptation during adolescence (Doyle & Cicchetti, 2017). Specifically, adolescence marks a crucial period in which biological, psychological, and social development take place in the context of developmentally salient social tasks (Steinberg et al., 2006). Therefore, disrupted interpersonal trust resulting from early attachment relationships may lead to heightened risk for a range of negative psychosocial outcomes in adolescence, particularly those involving interpersonal relationships.

Interpersonal Trust and the IPTS

Although it has yet to be tested, interpersonal trust may also be associated with thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Rotenberg (1994) proposed that individuals with low trust are less willing to initiate contact or share personal information with others, which serves to maintain loneliness and poor social support. The empirical literature also supports an association between interpersonal trust beliefs and loneliness, the number of friendships youth have, and social disengagement (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993; Rotenberg et al., 2010). Taken together, evidence suggests that interpersonal trust beliefs are conceptually linked with aspects of thwarted belongingness, including loneliness, poor social support, and social disengagement.

Interpersonal trust may also play a role in the development of perceived burdensomeness. Trust in caregivers is thought to be crucial in the development of healthy self-esteem (Rotenberg et al., 2005), and lower trust has been empirically related to lower self-esteem in adults (Lundberg & Kristenson, 2008). Low levels of interpersonal trust may thus lead to low self-esteem, worthlessness, and ultimately to self-hatred and the belief that one is a liability to others, which are core features of perceived burdensomeness (Joiner, Ribeiro, & Silva, 2012). Additionally, interpersonal trust allows an individual to rely on others in risk-taking situations (Rotenberg, 2010). Those with low interpersonal trust beliefs may be unwilling to rely on others and develop the misperception that doing so presents an undue burden.

Despite potential links between interpersonal trust and both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, these associations have not yet been empirically examined. In addition, interpersonal trust has rarely been examined in relation to adolescent suicide-related behaviors, and findings, to date, have been mixed. While previous evidence demonstrated a positive relation between trust and suicide ideation in adolescents (Lester & Gatto, 1990), more recent studies suggest a negative association (Langille, Asbridge, Kisely, & Rasic, 2012; Venta, Hatkevich, Sharp, & Rotenberg, 2017).

The present study sought to further inform the empirical literature with regard to the association between interpersonal trust and suicide ideation in adolescence. Utilizing the framework of the IPTS, in this study we hypothesized that greater interpersonal trust, as comprised by reliability, emotional trust, and honesty, would be directly associated with lower perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. We also hypothesized that interpersonal trust would be negatively associated with suicide ideation indirectly, via associations with perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. While the cross-sectional nature of our study design limits any temporal inferences to be made about these constructs, we based our model on theoretical literature that suggests that the foundations of interpersonal trust are based in early attachment relationships between infants and caregivers (Fonagy, Luyten, & Allison, 2015). Therefore, although it is the case that interpersonal trust is dynamic and changes over time in association with psychological symptoms (Joiner & Metalsky, 1995), for the current study, it is conceptualized as a distal risk factor based on research suggesting that early attachment relationships are the basis from which individuals learn to trust (Corriveau et al., 2009). Further, the constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are higher order cognitive constructs that would be assumed to develop later in life, with emerging literature demonstrating temporal associations between perceived burdensomeness/thwarted belongingness and suicide ideation (Hill, del Busto, Buitron, & Pettit, in press). Particularly, these constructs are relevant during adolescence which is marked by transformations in the personal and interpersonal realm. Maladaptive cognitions arising from distorted interpersonal trust are particularly harmful in adolescence, which is a time of significant risk for negative psychosocial outcomes (Collins & Steinberg, 2006).

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

Adolescent participants were consecutively admitted inpatients at a university-affiliated acute-care psychiatric hospital serving a large urban area. After the nature of the study was explained, parents provided informed consent for their adolescent child to participate. Of those with parental consent, 411 adolescents provided assent to participate, 67 declined to participate, 41 were excluded due to severe psychosis and/or intellectual disability, and 168 were discharged prior to completing the assessment. Data for the present analysis were drawn from a subset of adolescents (n = 387) who participated during the period when all of the measures included in this analysis were part of the study protocol. The data for these analyses were derived from the same larger study as Venta et al.’s (2017) results, which found that adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms who had low interpersonal trust in their mothers reported the highest number of suicide attempts.

Participants (63.6% female) ranged in age from 12 to 17 years (M = 14.72, SD = 1.49) and identified as Hispanic (37.5%), African American or Black (26.9%), Caucasian (25.8%), multiracial (6.5%), Southeast Asian (1.6%), South Asian (0.3%), and Native American (0.3%). Regarding severity of psychopathology, average T-scores on the Youth Self-Report scales (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) were elevated for depressive problems (M = 67.83.72, SD = 11.29), anxiety problems (M = 59.95, SD = 8.41), somatic problems (M = 58.86, SD = 9.88), attention deficit/hyperactivity problems (M = 61.58, SD = 8.17), oppositional defiant problems (M = 61.41, SD = 8.57), and conduct problems (M = 65.27, SD = 9.91). This study was conducted as approved by the appropriate institutional review boards.

Measures

Thwarted Belongingness and Perceived Burdensomeness.

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-15 (INQ; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012) is a 15-item measure of perceived burdensomeness (6-item subscale) and thwarted belongingness (9-item subscale). Participants respond to each item using a 7-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate greater perceptions that one is a burden to others (perceived burdensomeness) and does not feel connected to others (thwarted belongingness). Prior research has supported the factor structure, internal consistency, and convergent validity of the subscales in adolescents (Hill et al., 2015). Internal consistency coefficients in the present sample were α = .91 for perceived burdensomeness and α = .82 for thwarted belongingness.

Suicide Ideation.

The Modified Scale for Suicide Ideation (MSSI; Miller, Norman, Bishop, & Dow, 1986) is an 18-item clinician rating scale of suicide ideation. Each item is rated from 0 to 3 and the total score ranges from 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating greater suicide ideation. The internal consistency, interrater reliability, and factor structure of the MSSI have been supported among adolescents (Pettit et al., 2009). Concurrent and discriminant validity have been adequately supported (Miller et al., 1986; Pettit et al., 2009). Internal consistency in the present sample was α = .93.

Interpersonal Trust.

The Children’s Generalized Trust Belief Scale (CGTB; Rotenberg et al., 2005) is a 24-item measure of interpersonal trust beliefs across three bases: reliability, honesty, and emotional trust. Each item consists of a hypothetical situation regarding a relationship between a child and their parent, teacher, or peers. Each item is rated from 1 to 5 with scores generated for reliability, honesty, and emotional trust. Scores in each domain range from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater interpersonal trust. Reliability and validity have been supported among pre-adolescents (Rotenberg et al., 2005, 2014) and adolescents (Betts, Houston, Steer, & Gardner, 2016). Internal consistency in the present sample was α = .70 for reliability, .64 for emotional trust, .66 for honesty, and .82 for the overall 24-item scale.

Depressive Symptoms.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item measure of depressive symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria. Items are rated from 0 to 3 based on symptom severity over the previous 2 weeks. Total scores range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. The BDI-II has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity in adolescent inpatient samples (Osman, Kopper, Barrios, Gutierrez, & Bagge, 2004). Internal consistency in the present sample was α = .92. For the present analysis, to avoid conceptual overlap between the depressive symptom and suicide ideation measures, the suicide ideation item was omitted from BDI-II total scores.

Data Analysis

Missing data were evaluated via Little’s MCAR test, which was not statistically significant, χ2 (232) = 247.31, p = .23. Data were assumed to be at least missing at random (MAR) and an expectation maximization algorithm was used to account for missing data prior to analysis. Data were then evaluated for multivariate outliers by examining leverage indices for each individual. An outlier was defined as a leverage score four times greater than the mean leverage; no outliers were identified. Based on the recommendations of Field (2009) for skewness and kurtosis in large samples, Z scores were calculated for skew and kurtosis and Z scores with an absolute value > 3.29 were considered evidence of violations of normality. As a result of platykurtic distributions of perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation, robust maximum likelihood (MLR) was used to estimate models. Indirect effects were examined via structural equation models. A robust maximum likelihood procedure was used to generate several indices of model fit in order to evaluate how well the model represented the data. A model that accurately represents the data should generate a nonsignificant chi-squared value, confirmatory factor index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) values > 0.95, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06, and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2011).

RESULTS

Means and standard deviations of study variables, as well as correlations between them, are provided in Table 1. Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicide ideation were significantly and negatively correlated with each of the dimensions of interpersonal trust. Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicide ideation were also significantly and positively correlated with one another. Each of the interpersonal trust domains were significantly and positively correlated with one another.

TABLE 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of, and Correlations Between, Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean | (SD) | Skew | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Thwarted Belongingness | – | 33.19 | (12.04) | −0.34 | −2.78 | ||||||

| 2. Perceived Burdensomeness | .54*** | − | 22.53 | (10.74) | 0.08 | −4.42 | |||||

| 3. Suicide Ideation | .42*** | .66*** | − | 18.17 | (13.61) | 0.66 | −4.54 | ||||

| 4. Interpersonal Trust: Reliability | −.22*** | −.25*** | −.17** | − | 28.26 | (6.39) | −2.59 | 1.53 | |||

| 5. Interpersonal Trust: Emotional Trust | −.21*** | −.20*** | −.14** | .48*** | − | 25.78 | (5.32) | −1.23 | 1.18 | ||

| 6. Interpersonal Trust: Honesty | −.30*** | −.18** | −.12** | .37*** | .38*** | − | 23.00 | (3.13) | −0.18 | −0.56 | |

| 7. Depressive Symptoms | .57*** | .68*** | .68*** | −.24*** | −.16** | −.24** | 21.50 | (12.00) | 1.11 | −2.55 |

Note. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness = INQ subscale scores; suicide ideation = MSSI total score; relability, emotional, and honesty = CGTB subscale scores; depressive symptoms = BDI-II total score; skew and kurtosis values provided as Z scores.

p < .01;

p < .001.

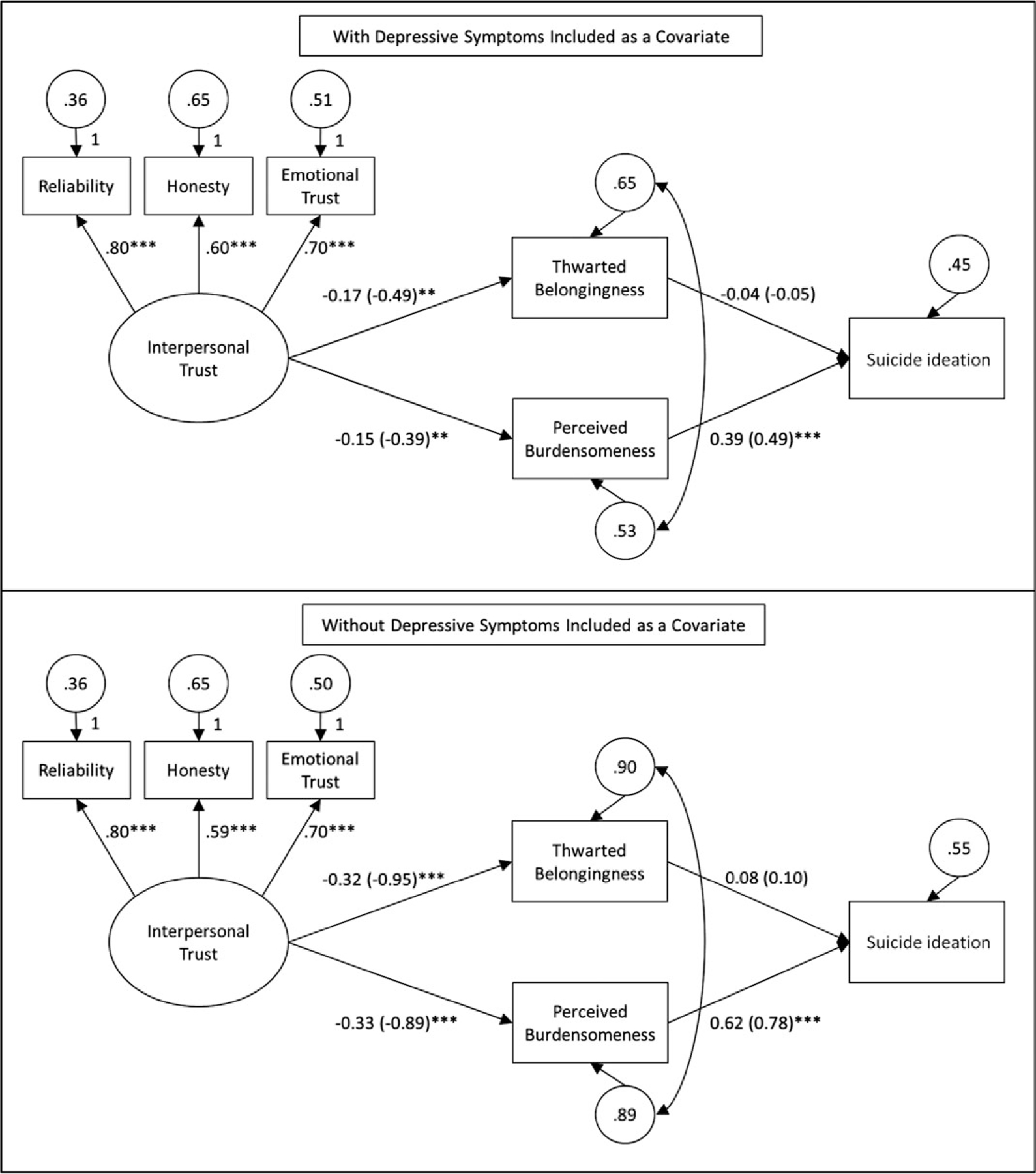

To examine the associations between interpersonal trust, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide ideation a structural equation model was fit to the data, as depicted in Figure 1. Interpersonal trust was identified as a latent construct, with all three domains loading onto a single overall construct. In addition to the paths depicted in Figure 1, depressive symptoms were included as a covariate, with paths from depressive symptoms to each endogenous variable. A variety of indices of model fit were evaluated and uniformly pointed toward good model fit, χ2 (9) = 9.07, p = .43, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.01, Standardized RMR = 0.02. Figure 1 presents the parameter estimates for the coefficients. Standardized coefficients appear for each parameter, with unstandardized coefficients in parentheses. The point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each of the unstandardized path coefficients in the model are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model of Indirect Effects from Interpersonal Trust to Suicide Ideation. Note. Standardized path coefficients estimated using STDYX standardization, unstandardized path coefficients in parentheses.

**p < .01, ***p < .001.

TABLE 2.

Unstandardized Point Estimates and Confidence Intervals for the Indirect Effect Model

| Path | With depressive symptoms covaried |

Without depressive symptoms covaried |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point estimate | 95% Confidence interval | Point estimate | 95% Confidence interval | |

| Interpersonal Trust to thwarted belongingness | −0.49 | −0.84, −0.15 | −0.95 | −1.34, −0.54 |

| Interpersonal trust to perceived burdensomeness | −0.39 | −0.65, −0.13 | −0.89 | −1.27, −0.52 |

| Thwarted belongingness to suicide ideation | −0.05 | −0.14, 0.05 | 0.10 | −0.01, 0.21 |

| Perceived burdensomeness to suicide ideation | 0.49 | 0.36, 0.63 | 0.78 | 0.67, 0.90 |

| Interpersonal trust to thwarted belongingness to suicide ideation | 0.02 | −0.03, 0.07 | −0.10 | −0.20, 0.01 |

| Interpersonal trust to perceived burdensomeness to suicide ideation | −0.19 | −0.32, −0.06 | −0.70 | −1.01, −0.39 |

The model predicted 35.2% of the variance in thwarted belongingness, 47.5% of the variance in perceived burdensomeness, and 54.6% of the variance in suicide ideation. In addition to the direct paths depicted in Figure 1, the model suggests indirect paths from the latent interpersonal trust construct to suicide ideation via thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. The indirect path via perceived burdensomeness was statistically significant, but the indirect path via thwarted belongingness was not significant. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effects are provided in Table 2. For the path from interpersonal trust to suicide ideation via perceived burdensomeness, the model suggests that a 1 point increase in interpersonal trust was associated with a 0.19 point decrease in suicide ideation.

A similar analysis was conducted in which depressive symptoms were not included as a covariate. Indices of model fit were evaluated and uniformly pointed toward good model fit, χ2 (7) = 5.03, p = .65, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.01, Standardized RMR = 0.01. Results are presented in the bottom half of Figure 1 nd Table 2 presents the point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each of the unstandardized path coefficients in the model. The model predicted 10.2% of the variance in thwarted belongingness, 11.0% of the variance in perceived burdensomeness, and 44.9% of the variance in suicide ideation. The indirect path via perceived burdensomeness was statistically significant, but the indirect path via thwarted belongingness was not significant. For the path from interpersonal trust to suicide ideation via perceived burdensomeness, the model suggests that a 1 point increase in interpersonal trust was associated with a 0.70 point decrease in suicide ideation score.

An additional model was examined, in which a direct path from interpersonal trust to suicide ideation was added. A Satorra–Bentler chi-squared difference test for nested models revealed the models did not significantly differ in appropriateness of fit. Thus, the simpler model without the direct path from interpersonal trust to suicide ideation was retained.

DISCUSSION

The present study evaluated associations between interpersonal trust, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicide ideation. Results indicated that interpersonal trust was negatively associated with both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as well as with suicide ideation. Further, the analysis provided support for an indirect effects model in which interpersonal trust was associated with suicide ideation via perceived burdensomeness.

The presence of significant associations between interpersonal trust and both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness suggests that adaptive interpersonal trust beliefs may help protect against these cognitions. The association between interpersonal trust and thwarted belongingness may be due to the effect of interpersonal trust on social relationships (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993; Rotenberg et al., 2010). The mechanism through which interpersonal trust is associated with perceived burdensomeness is less clear, although the empirical literature suggests that low self-esteem may be implicated (Lundberg & Kristenson, 2008). Additional research is needed to examine the causal mechanisms and developmental processes that result in burdensome cognitions among adolescents. Furthermore, the present study considered interpersonal trust as a distal factor; however, it may (also) serve as a proximal, dynamic factor that waxes and wanes with, and may be exacerbated by, depressive symptoms. Evidence demonstrates dynamic relations between depressive symptoms and other interpersonal constructs (i.e., excessive-reassurance and negative-feedback seeking behaviors; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995), and thus evaluating the present study variables across multiple time points may prove to be informative. Current cross-sectional findings suggest that such an investigation may be warranted.

In the present study we examined the associations between interpersonal trust beliefs and perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide ideation both with and without depressive symptoms included in the model. Both models produce a similar pattern of results. However, because depressive symptoms and interpersonal trust are correlated, the model without depressive symptoms has larger path coefficients, resulting in larger estimated indirect effects. When controlling for the impact of depressive symptoms, the indirect effects are reduced, demonstrating the unique contribution of interpersonal trust, beyond the impact of depressive symptoms. As Rogers et al. (2016) demonstrated, controlling for depression results in a suicide ideation variable comprised primarily of fearlessness about death and externalizing pathology, which differs from traditional views of what suicide ideation comprises. As a result, interpreting a model that includes depressive symptoms should be made in the context of that alternative conceptualization of suicide ideation.

These results also provide preliminary evidence to suggest that interventions that promote adaptive interpersonal trust beliefs should be examined as possible means for preventing the development of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and, ultimately, suicide ideation. For example, attachment-based family therapy (Diamond, Diamond, & Levy, 2014), an empirically supported treatment for depressed adolescents, works to rebuild trust between adolescents and parents (Diamond, Russon, & Levy, 2016). Similarly, trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy (CBT; Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006) aims to help the adolescent to trust the therapist and eventually to generalize this to other people, such as caregivers (Cohen, Mannarino, Kliethermes, & Murray, 2012). Mentalization-based treatment for adolescents (Rossouw & Fonagy, 2012) posits that improved mentalization enhances trust by increasing the capacity to understand social information, and has been shown to improve peer and parent trust in adolescents with borderline personality symptoms (Bo et al., 2016). Mentalization-based therapy (MBT; Bateman & Fonagy, 2012) also explicitly integrates the construct of “epistemic trust” into its approach (Allison & Fonagy, 2016; Bo, Sharp, Fonagy, & Kongerslev, 2015). MBT refers to the construct of “epistemic trust” as “an individual’s willingness to consider communication conveying the knowledge from someone as trustworthy, generalizable, and relevant to the self” (Fonagy & Luyten, 2016, p. 766). Epistemic trust is understood to develop in the context of secure attachment relationships with primary caregivers in which the child learns that the information the caregiver provides about the world, the child herself, and the attachment relationship is meaningful, relevant, and trustworthy. The child opens herself up for learning (“the epistemic highway”) and accepts instruction regarding the world and how to cope with the world. This openness to instruction (or pedagogy) spills over to other close relationships (teachers and peers) and builds resilience. Similarly, CBT for depression often includes a parent/family intervention component (David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008) and focuses on cognitive restructuring for maladaptive thoughts as well as skills to improve communication, social relationships, and conflict resolution that may further improve interpersonal trust. Interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A) has also been found to be effective in treating adolescent depression and focuses more explicitly on family and relational problems that may address trust (Mufson, Dorta, Moreau, & Weissman, 2004; Mufson, Dorta, Wickramaratne, Nomura, Olfson, & Weissman, 2004). Universal and selected programs that increase interpersonal trust may operate as more distal prevention strategies. For example, the good behavior game (GBG; Barrish, Saunders, & Wolf, 1969), which creates teams within early elementary classrooms to reduce problem behaviors and foster social support and a positive classroom environment, is a school-based prevention program that has been shown to reduce suicide ideation and attempts over a 15-year follow-up period (Wilcox et al., 2008). Programs developed for use with adolescent populations, particularly those that target positive interpersonal skills or relationship development, may also be useful for preventive intervention. Programs like the Interpersonal Therapy-Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST; Young, Mufson, & Gallop, 2010) or the LEAP intervention (Hill & Pettit, 2016) address forming and maintaining positive relationships, and may impact adaptive interpersonal trust beliefs.

The aforementioned studies indicate that interpersonal trust is modifiable and amenable to change via psychosocial intervention. Additional research is needed to determine if participation in these interventions, and any resulting change in interpersonal trust, also results in reductions in thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Existing intervention components that increase interpersonal trust beliefs may also be useful for the development of novel interventions for reducing thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness and preventing suicide ideation. Future intervention development may benefit from identifying treatment elements associated with increased trust beliefs in adolescents and adapting those elements for use in universal and selective preventive interventions.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results of this study should be evaluated within the context of the study’s strengths and limitations. The study utilized a diverse sample of adolescent psychiatric inpatients; however, the acute nature of the inpatient unit may limit the generalizability of the findings to other adolescent samples. Furthermore, adolescents were in a position in which perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may have been situationally elevated at time of assessment, given that many were admitted for recent suicide attempts and/or familial stress. The present study was cross-sectional in nature and was unable to evaluate a temporal or causal sequence from interpersonal trust beliefs to suicide ideation. Although measured cross-sectionally, interpersonal trust beliefs are viewed as an element of personality (Rotenberg et al., 2005) and are thought to develop early in life (Erikson, 1963) and so may reasonably be thought to precede the development of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Further, previous research has demonstrated that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness predict suicide ideation longitudinally (Van Orden et al., 2012), which lends support to the temporal sequence from the IPTS factors to suicide ideation. However, previous research and theory is not a substitute for longitudinal research and these findings must be replicated longitudinally. Finally, the preliminary nature of these findings precludes drawing firm clinical or empirical conclusions, but highlights the need for additional research examining the associations between interpersonal trust and the IPTS.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study evaluated associations between interpersonal trust, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicide ideation in adolescents. Results indicated support for an indirect effects model in which interpersonal trust was associated with suicide ideation via its association with perceived burdensomeness. These results identify interpersonal trust as a potential factor in the development of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness and as a potential target for early interventions aimed at preventing suicide ideation. Future research should further evaluate the role of interpersonal trust in the development of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness and evaluate potential mechanisms for modifying interpersonal trust.

Contributor Information

RYAN M. HILL, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

FRANCESCA PENNER, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

SALOME VANWOERDEN, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

WILLIAM MELLICK, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

IRAM KAZIMI, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

CARLA SHARP, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

REFERENCES

- ACHENBACH TM, & RESCORLA LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- ALLISON E, & FONAGY P (2016). When is truth relevant? Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 85, 275–303. 10.1002/psaq.2016.85.issue-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRISH HH, SAUNDERS M, & WOLF MM (1969). Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 2, 119–124. 10.1901/jaba.1969.2-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BATEMAN AW, & FONAGY P (2012). Mentalization-based treatment of borderline personality disorder New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BECK AT, STEER RA, & BROWN GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- BETTS LR, HOUSTON JE, STEER OL, & GARDNER SE (2016). Adolescents’ experiences of victimization: The role of attribution style and generalized trust. Journal of School Violence, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- BO S, SHARP C, BECK E, PEDERSEN J, GONDAN M, & SIMONSEN E (2016). First empirical evaluation of outcomes for mentalization-based group therapy for adolescents with BPD. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8, 396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BO S, SHARP C, FONAGY P, & KONGERSLEV M (2015). Hypermentalizing, attachment, and epistemic trust in adolescent BPD: Clinical illustrations. Personal Disordors, 8, 172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWLBY J (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- BUITRON V, HILL RM, PETTIT JW, GREEN KL, HATKEVICH C, & SHARP C (2016). Interpersonal stress and suicidal ideation in adolescence: An indirect association through perceived burdensomeness toward others. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 143–149. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN JA, MANNARINO AP, & DEBLINGER E (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- COHEN JA, MANNARINO AP, KLIETHERMES M, & MURRAY LA (2012). Trauma-focused CBT for youth with complex trauma. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36, 528–541. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS WA, & STEINBERG L (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. Handbook of Child Psychology, 57, 255–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORRIVEAU KH, HARRIS PL, MEINS E, FERNYHOUGH C, ARNOTT B, ELLIOTT L, et al. (2009). Young children’s trust in their mother’s claims: Longitudinal links with attachment security in infancy. Child development, 80, 750–761. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVID-FERDON C, & KASLOW NJ (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 62–104. 10.1080/15374410701817865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIAMOND GS, DIAMOND GM, & LEVY SA (2014). Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press. 10.1037/14296-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DIAMOND G, RUSSON J, & LEVY S (2016). Attachment-based family therapy: A review of the empirical support. Family Process, 55, 595–610. 10.1111/famp.2016.55.issue-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOYLE C, & CICCHETTI D (2017). From the cradle to the grave: The effect of adverse caregiving environments on attachment and relationships throughout the lifespan. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24, 203–217. 10.1111/cpsp.12192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSON E (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- FIELD A (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- FONAGY P, & LUYTEN P (2016). A multilevel perspective on the development of borderline personality disorder. In Cichetti DC (Ed.), Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 3 (pp. 726–792). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- FONAGY P, LUYTEN P, & ALLISON E (2015). Epistemic petrification and the restoration of epistemic trust: A new conceptualization of borderline personality disorder and its psychosocial treatment. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29, 575–609. 10.1521/pedi.2015.29.5.575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL RM, DEL BUSTO CT, BUITRON V, & PETTIT JW (In press). Depressive symptoms and perceived burdensomeness mediate the association between anxiety and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL RM, & PETTIT JW (2013). The role of autonomy needs in suicidal ideation: Integrating the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide and self-determination theory. Archives of Suicide Research, 17, 288–301. 10.1080/13811118.2013.777001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL RM, & PETTIT JW (2014). Perceived burdensomeness and suicide-related behaviors: Current evidence and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 631–643. 10.1002/jclp.2014.70.issue-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL RM, & PETTIT JW (2016). Pilot randomized controlled trial of LEAP: A program to reduce adolescent perceived burdensomeness. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 1–12. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1188705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL RM, REY Y, MARIN CE, SHARP C, GREEN KL, & PETTIT JW (2015). Evaluating the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire: Comparison of the reliability, factor structure, and predictive validity across five versions. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45, 302–314. 10.1111/sltb.2015.45.issue-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HU LT, & BENTLER PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- JOINER TE JR. (2005). Why people die by suicide Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- JOINER TE, & METALSKY GI (1995). A prospective test of an integrative interpersonal theory of depression: A naturalistic study of college roommates. Journal of personality and social psychology, 69, 778. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOINER TE, RIBEIRO JD, & SILVA C (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their co-occurrence as viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 342–347. 10.1177/0963721412454873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- KANN L, MCMANUS T, HARRIS WA, SHANKLIN SL, FLINT KH, HAWKINS J, et al. (2016). Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 65, 1–174. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINE RB (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- LANGILLE DB, ASBRIDGE M, KISELY S, & RASIC D (2012). Suicidal behaviours in adolescents in Nova Scotia, Canada: Protective associations with measures of social capital. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 1549–1555. 10.1007/s00127-011-0461-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LESTER D, & GATTO JL (1990). Interpersonal trust, depression, and suicidal ideation in teenagers. Psychological Reports, 67, 786. 10.2466/PR0.67.7.786-786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDBERG J, & KRISTENSON M (2008). Is subjective status influenced by psychosocial factors? Social Indicators Research, 89, 375–390. 10.1007/s11205-008-9238-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MALTI T, AVERDIJK M, RIBEAUD D, ROTENBERG KJ, & EISNER MP (2013). “Do you trust him?” Children’s trust beliefs and developmental trajectories of aggressive behavior in an ethnically diverse sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 445–456. 10.1007/s10802-012-9687-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER IW, NORMAN WH, BISHOP SB, & DOW MG (1986). The Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 724–725. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.5.724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUFSON L, DORTA KP, MOREAU D, & WEISSMAN MM (2004). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- MUFSON L, DORTA KP, WICKRAMARATNE P, NOMURA Y, OLFSON M, & WEISSMAN MM (2004). A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 577–584. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSMAN A, KOPPER BA, BARRIOS F, GUTIERREZ PM, & BAGGE CL (2004). Reliability and validity of the Beck Depression Inventory–II with adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Psychological Assessment, 16(2), 120–132. 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARKER JG, & ASHER SR (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PETTIT JW, GARZA MJ, GROVER KE, SCHATTE DJ, MORGAN ST, HARPER A, et al. (2009). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation among suicidal youth. Depression and Anxiety, 26, 769–774. 10.1002/da.v26:8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROGERS ML, STANLEY IH, HOM MA, CHIURLIZA B, PODLOGAR MC, & JOINER TE (2016). Conceptual and empirical scrutiny of covarying depression out of suicidal ideation. Assessment, 1–14. 10.1177/10731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSSOUW TI, & FONAGY P (2012). Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 1304–1313. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTENBERG KJ (1994). Loneliness and interpersonal trust. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13, 152–173. 10.1521/jscp.1994.13.2.152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ROTENBERG KJ (2010). The conceptualization of interpersonal trust: A basis, domain, and target framework. In Rotenberg KJ (Ed.), Interpersonal trust during childhood and adolescence (pp. 8–27). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511750946 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ROTENBERG KJ, ADDIS N, BETTS LR, CORRIGAN A, FOX C, HOBSON Z, et al. (2010). The relation between trust beliefs and loneliness during early childhood, middle childhood, and adulthood. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36, 1086–1100. 10.1177/0146167210374957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTENBERG KJ, FOX C, GREEN S, RUDERMAN L, SLATER K, STEVENS K, et al. (2005). Construction and validation of a children’s interpersonal trust belief scale. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 23, 271–292. 10.1348/026151005X26192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ROTENBERG KJ, QUALTER P, HOLT NL, HARRIS RA, HENZI P, & BARRETT L (2014). When trust fails: The relation between children’s trust beliefs in peers and their peer interactions in a natural setting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 967–980. 10.1007/s10802-013-9835-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEPHERD DS, GUREWICH D, LWIN AK, REED GA, & SILVERMAN MM (2016). Suicide and suicidal attempts in the United States: Costs and policy implications. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46, 352–362. 10.1111/sltb.2016.46.issue-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMPSON JA (2007a). Psychological foundations of trust. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 264–268. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00517.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SIMPSON JA (2007b). Foundations of interpersonal trust. In Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, & Kruglanski AW (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2nd ed., pp. 587–607). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- STEINBERG L, DAHL R, KEATING D, KUPFER DJ, MASTEN AS, & PINE DS (2006). The study of developmental psychopathology in adolescence: Integrating affective neuroscience with the study of context. In Cicchetti D & Cohen DJ (Eds), Developmental psychopathology: Developmental neuroscience (Vol. 2, 2nd ed. pp. 710–741). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- STEWART SM, EADDY M, HORTON SE, HUGHES J, & KENNARD B (2015). The validity of the interpersonal theory of suicide in adolescence: A review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46, 437–449. 10.1002/da.20664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TUCKER RP, & WINGATE LR (2014). Basic need satisfaction and suicidal ideation: A self-determination perspective on interpersonal suicide risk and suicidal thinking. Archives of Suicide Research, 18, 282–294. 10.1080/13811118.2013.824839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN ORDEN KA, CUKROWICZ KC, WITTE TK, & JOINER TE (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24, 197–215. 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN ORDEN KA, WITTE TK, CUKROWICZ KC, BRAITHWAITE SR, SELBY EA, & JOINER TE (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117, 575–600. 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VENTA A, HATKEVICH C, SHARP C, & ROTENBERG K (2017). Emotional trust in mothers serves as a buffer against suicide attempts in inpatient adolescents with depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 36, 221–237. 10.1521/jscp.2017.36.3.221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WENTZEL KR (1991). Relations between social competence and academic achievement in early adolescence. Child Development, 62, 1066–1078. 10.2307/1131152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILCOX HC, KELLAM SG, BROWN CH, PODUSKA JM, IALONGO NS, WANG W, et al. (2008). The impact of two universal randomized first- and second-grade classroom interventions on young adult suicide ideation and attempts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95(Suppl. 1), S60–S73. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOUNG JF, MUFSON L, & GALLOP R (2010). Preventing depression: A randomized trial of interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training. Depression and Anxiety, 27, 426–433. 10.1002/da.20664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]