Abstract

Purpose: To compare the diagnostic accuracy and safety of computed tomography (CT)-guided core needle biopsy (CNB) between pulmonary ground-glass and solid nodules using propensity score matching (PSM) method and determine the relevant risk factors. Methods: This was a single-center retrospective cohort study using data from 665 patients who underwent CT-guided CNB of pulmonary nodules in our hospital between May 2019 and May 2021, including 39 ground-glass nodules (GGNs) and 626 solid nodules. We used a 1:4 PSM analysis to compared the diagnostic yields and complications rates of CT-guided CNB between 2 groups. Results: After PSM, 170 cases involved in the comparison (34 GGNs vs 136 solid nodules) were randomly matched (1:4) by patient demographics, clinical history, lesion characteristics, and procedure-related factors. There was no statistically significant difference in the diagnostic yields and complications rates between 2 groups. Significant pneumothorax incidence increase was noted at small lesion size, deep lesion location, and traversing interlobar fissure (P < .05). Post-biopsy hemorrhage was a protective factor for pneumothorax (P < .05). The size/proportion of consolidation of GGN did not influence the diagnostic accuracy and complication incidence (P > .05). Conclusions: The accuracy and safety of CT-guided CNB were comparable for ground-glass and solid nodules and the size/proportion of consolidation of GGN may be not a relevant risk factor. The biopsy should avoid traversing interlobar fissure as far as possible. Smaller lesion size and deeper lesion location may lead to higher pneumothorax rate and post-biopsy hemorrhage may be a protective factor for pneumothorax.

Keywords: CT-guided core needle biopsy, pulmonary nodule, ground-glass, solid, propensity score matching

Introduction

Along with the wide implementation of high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) and the popularity of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung cancer screening, the radiographic feature, “ground-glass opacity” (GGO) or “ground-glass nodule” (GGN), was introduced. GGN is defined as small nodules with hazy opacity on HRCT, through which pulmonary vessels or bronchial structures can be visualized. GGN is a nonspecific radiologic finding that can indicate inflammatory disease, focal fibrosis, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH), adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA). 1

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommended that if the part-solid nodule is suspected of being highly malignant by chest CT + contrast and/or positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, or following CT scan shows that the tumor size has increased by more than 1.5 mm in ≥20 mm nonsolid nodule, patients should consider invasive diagnosis, such as biopsy or surgical resection. 2 Surgical resection has the highest diagnosis rate, but is not recommended to be as a diagnostic tool for early stage lung cancer. CT-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has been reported to be useful for peripheral small lung cancers but is not clinically practical due to the low diagnostic accuracy for GGNs. CT-guided core needle biopsy (CNB) is a common radiological minimally invasive procedure to confirm the neoplastic nature of the lesion and also characterize its genotypic and molecular peculiarities with a slightly higher complication rate but a superior diagnostic accuracy. However, compared with solid nodules, the diagnostic accuracy and safety of CT-guided biopsy for GGNs are still uncertain.

In this retrospective analysis, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy and complications rates of CT-guided CNB for GGNs and compared them with solid nodules based on propensity score matching (PSM) method.

Materials and Methods

Study Patients and Data Collection

This was a single-center retrospective cohort study. We performed the study in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. 3 Data from patients with pulmonary nodules who underwent computed tomography (CT)-guided CNB in our hospital between May 2019 and May 2021 were retrospectively collected. Inclusion criteria: (1) lung window image data with scanning thickness of 1.25 mm; (2) biopsy diagnosis with detailed pathological results; and (3) definite final diagnosis, such as surgical pathology or clinical follow-up results. Exclusion criteria: (1) target lesion located in mediastinum, chest wall, or pleura and (2) incomplete data. By examining medical and procedure records, patient demographics, clinical histories, lesion characteristics, procedure-related factors, final biopsy report and surgical pathology or clinical follow-up result were reviewed. Additionally, the consolidation-to-tumor ratio (CTR) was defined as the ratio of solid portion size to total size in the lung window (window width: 1600 HU; window level, −600 HU). 4 The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (No. 2021057). We have de-identified all patient details.

Biopsy Procedure

There was one case with multiple primary GGNs. We chose biopsy target lesions in which imaging assessment was high for malignancy (eg high solid proportion, spiculated margin) and the procedure was relatively safe (eg closer to the pleura, no traversing interlobar fissure). Finally, we included 2 mixed GGNs as separate cases, respectively.

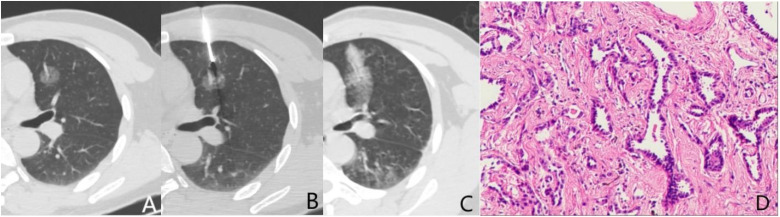

CT-guided CNB was performed by experienced interventional radiologists with more than 10 years of experience. The biopsy procedure is shown in Figure 1A to C. Figure 1D is the final pathological result. Following were specific steps 5 : (1) Preoperative preparation: Coagulation function, cardiopulmonary function, and platelets were checked. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before each biopsy. (2) Localization: Patient decubitus on the CT bed was prone, supine, or lateral, depending on the nodule localization. The low-dose scan prior to the biopsy was performed using a conventional CT Scanner (PHILIPS CT Ingenuity Flex, Royal Dutch Philips Electronics Ltd). Laser positioning and metal skin markers were used to indicate the site of needle entry and direction of approach for biopsy and the thickness of the thoracic wall was measured from the skin marker to the pleural surface to determine the depth of anesthesia required and the depth of needle insertion. (3) Lung biopsy: Using sterile technique, local anesthesia was employed with 2% lidocaine. The anesthesia needle was inserted into the chest wall pleura as the locating needle. Satisfactory position of the needle tip within the target lesion was confirmed on CT before sampling. The biopsy was performed using a full-automated 18-gauge biopsy system of a 2 cm throw length needle (Bard® Max-Core® Core Needle Biopsy Instrument; Bard Biopsy Systems). Biopsied specimens were fixed in buffered 10% neutral formalin and sent to the pathological department for further analyses. In general, to ensure that the tissue block was sufficient for histological examination, the biopsy was repeated 2 to 3 times or more, with slight adjustment of the transthoracic puncture angle and depth used. (4) Postoperative management: After removing the needle from the patient, immediate follow-up CT was performed to detect complications. Patients rested for a minimum of 1 h after biopsy for clinical observation.

Figure 1.

A 49-year-old male underwent CT-guided CNB for pulmonary GGN detected by routine examination. (A) CT scan demonstrated a 1.7 cm pGGN at left upper lobe. The vessel inside was shown clearly. (B) The needle tip was about to puncture the lesion. (C) On the post-biopsy CT scan, hemorrhages along the needle pathway and around the lesion were seen. The lesion was covered. (D) The biopsy and surgical pathological results are consistent, which is considered as AAH ( × 100,HE).

Abbreviations: AAH: atypical adenomatous hyperplasia; CNB: core needle biopsy; GGN: ground-glass nodules.

Biopsy Results and Gold Standard

The biopsy diagnoses were classified into the following 3 categories: malignant (including AAH); benign; and nondiagnostic. If the pathological diagnosis is lung or other normal tissue, necrotic tissue, fibrous hyperplasia, or too little tissue to discriminate, the biopsy was defined as nondiagnostic. Diagnoses of malignant and benign diseases were considered as positive and negative results, respectively. False-positive or false-negative or nondiagnostic biopsy was defined as failed.

Gold standard of biopsied lesions was confirmed by independent surgical pathology or clinical follow-up. 5 AAH confirmed in the surgical specimen was included in the final diagnosis of malignancy. Clinical follow-ups of malignant lesions were accepted when the post-biopsy clinical course was consistent with obvious malignant processes (eg increased lesion size, lesion regression by chemotherapy, or appearance of metastasis). Clinical follow-ups of benign lesions were accepted when any of the following conditions were satisfied: (1) spontaneous resolution; (2) resolution after appropriate management such as antibiotics or corticosteroid treatment; and (3) benign morphology with no change on the serial follow-up CT.6,7

Complications Assessment

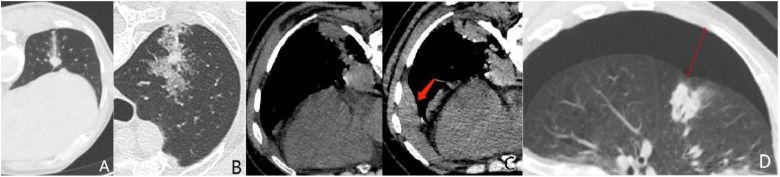

Two senior radiologists evaluated post-procedural complications including hemorrhage and pneumothorax by immediate follow-up CT (Figure 2). Pulmonary hemorrhage, defined as new consolidative or ground-glass opacity on post-biopsy images, was assessed for each procedure. Hemorrhage was classified into three grades modified from a previous hemorrhage grading scheme. 5 Grade 1 was defined as hemorrhage along the needle track (Figure 2A). Grade 2 was defined as perilesional hemorrhage (Figure 2B). Grade 3 was defined as hemothorax (Figure 2C) or hemoptysis. Hemoptysis was assessed by operator's procedural and review of patients’ medical records. Because grade 1 hemorrhage is often expected from our prior experience, we considered hemorrhage of grades 2 and 3 as higher grade. The severity of pneumothorax was measured on axial immediate follow-up CT images, defined as the maximum width of retraction of pulmonary surface. It was classified into grade 1 (1-10 mm), grade 2 (11-20 mm), and grade 3 (>20 mm) (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Common complications grading scheme of CT-guided CNB. (A) Grade 1 hemorrhage. (B) Grade 2 hemorrhage. (C) Grade 3 hemorrhage (hemothorax). The left is before biopsy; the right is after biopsy. (D) Grade 3 pneumothorax: the maximum width is 29 mm.

Abbreviation: CNB: core needle biopsy.

Propensity Score Matching

PSM analysis was conducted using the EmpowerStats 3.0 software. PSM was used to balance confounders between ground-glass and solid groups. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate propensity scores for each patient. A total of 18 relevant factors mentioned above were included in the regression model. PSM seeks to create 2 similar groups by matching them on a range of covariates.

In this study, one patient in the ground-glass group was matched to 4 patients in the solid group using nearest-neighbor matching without replacement and with a 0.05 caliper level. If the matching procedure was successful, there would be no differences in the covariates between the 2 groups, achieving covariate balance.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using the SPSS 22.0 software (IBM Corp.) and Microsoft Excel (2019). Accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and post-procedural complication rates were calculated for ground-glass and solid nodules after PSM. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors related to diagnostic accuracy and complications rates with the independent sample t-test and chi-square test for numeric and categorical values, respectively. Statistical significance was set at P <.05.

Results

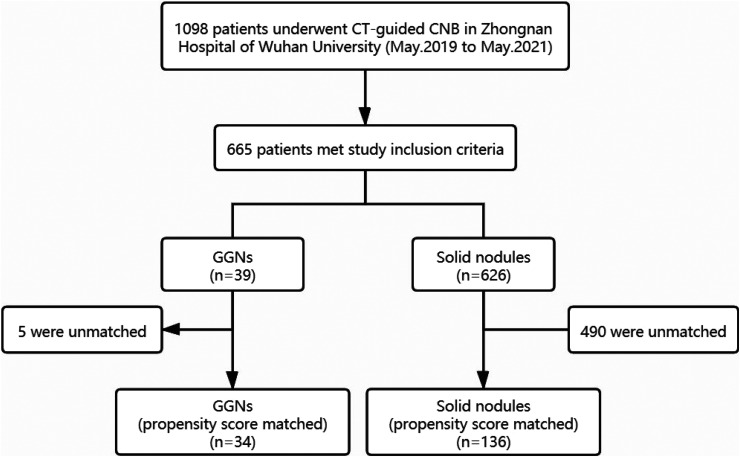

The study included 665 patients (39 GGNs; 626 solid nodules). The flow diagram of how the study population was selected and divided into 2 groups for propensity group matching is shown in Figure 3. Table 1 presents the results on the differences of potential confounders between the ground-glass and solid groups before and after PSM. There were imbalances between 2 groups in gender, smoking status, pleural effusion, lesion location, chest wall thickness, distance of the lesion from pleura, lesion size, lesion margin, and No. of sampling. Using the 1:4 PSM, 34 and 136 patients in the ground-glass and solid groups, respectively, were successfully matched.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of how the study population was selected and divided into 2 groups for propensity group matching.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 665 Patients Before and After PSM.

| Variables | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground-glass (n = 39) | Solid (n = 626) | P value | Ground-glass (n = 34) | Solid (n = 136) | P value | |

| Age (years) | .327 | .823 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 63.46 ± 11.1 | 61.7 ± 10.8 | 62.7 ± 10.3 | 63.1 ± 9.6 | ||

| Gender | <.001 | .219 | ||||

| Male | 15 | 422 | 13 | 68 | ||

| Female | 24 | 204 | 21 | 68 | ||

| Smoking status | .021 | .570 | ||||

| Yes | 11 | 295 | 10 | 47 | ||

| No | 28 | 331 | 24 | 89 | ||

| Chest surgery history | .550 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 34 | 3 | 12 | ||

| No | 36 | 592 | 31 | 124 | ||

| COPD/fibrosis | .712 | .348 | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 270 | 16 | 52 | ||

| No | 21 | 356 | 18 | 84 | ||

| Pleural effusion | .032 | .406 | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 117 | 2 | 4 | ||

| No | 37 | 509 | 32 | 132 | ||

| Lesion location | .024 | .168 | ||||

| Left upper | 14 | 162 | 12 | 41 | ||

| Left lower | 1 | 127 | 1 | 21 | ||

| Right upper | 16 | 179 | 13 | 41 | ||

| Right middle | 0 | 31 | 0 | 8 | ||

| Right lower | 8 | 127 | 8 | 25 | ||

| Chest wall thickness (mm) | .001 | .619 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 39.5 ± 13.1 | 33.1 ± 11.7 | 38.9 ± 13.4 | 37.5 ± 14.8 | ||

| Lung parenchyma density in the trajectory path (HU) | .062 | .310 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | −845.7 ± 77.7 | −797.6 ± 134.5 | −848.8 ± 78.1 | −826.7 ± 101.4 | ||

| Lesion–pleura distance (mm) | .030 | .256 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 11.1 ± 9.4 | 15.9 ± 13.8 | 11.7 ± 9.5 | 14.2 ± 12.0 | ||

| Lesion size (along the puncture direction, mm) | <.001 | .401 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 17.8 ± 7.8 | 28.7 ± 16.2 | 18.4 ± 8.1 | 20.0 ± 10.1 | ||

| Cavity | .850 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 5 | 87 | 5 | 20 | ||

| No | 34 | 539 | 29 | 116 | ||

| Lesion margin | .013 | .272 | ||||

| Smooth | 14 | 299 | 13 | 53 | ||

| Burred | 2 | 98 | 1 | 16 | ||

| Spiculated | 23 | 229 | 20 | 67 | ||

| Needle–pleura angle (°) | .869 | .910 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 73.1 ± 12.8 | 73.4 ± 13.4 | 73.2 ± 12.9 | 73.5 ± 13.3 | ||

| Traversing interlobar fissure | .194 | .072 | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 26 | 0 | 12 | ||

| No | 39 | 600 | 34 | 124 | ||

| No. of sampling | <.001 | .365 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | ||

| Patient position | .721 | .372 | ||||

| Prone | 21 | 298 | 19 | 59 | ||

| Supine | 9 | 152 | 7 | 30 | ||

| Lateral | 9 | 176 | 8 | 47 | ||

| Biopsy diagnosis | ||||||

| Nondiagnostic | 4 | 44 | 4 | 16 | ||

| Benign | 4 | 124 | .162 | 4 | 25 | .352 |

| Malignant | 31 | 458 | 26 | 95 | ||

| Final diagnosis | .278 | .131 | ||||

| Benign | 6 | 143 | 5 | 37 | ||

| Malignant | 33 | 483 | 29 | 99 | ||

Abbreviation: PSM: propensity score matching.

The diagnostic accuracy in GGNs was 88.2%, with 89.7% sensitivity, 80.0% specificity, 100% PPV, and 100% NPV (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in the diagnostic yields including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV between ground-glass and solid nodules (P > .05). Summaries of diagnostic success and failure in ground-glass and solid nodules groups were provided in Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1, respectively. By univariate logistic regression analysis, lesion margin and needle–pleura angle had statistically significant for diagnostic accuracy in GGNs and lesion location was statistically significant in solid group (P < .05).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Accuracy and Credibility of CT-guided CNB of Pulmonary Ground-Glass and Solid Nodules after PSM.

| All | Ground-glass (n = 34) | Solid (n = 136) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | 87.6 (149/170) | 88.2 (30/34) | 87.5 (119/136) | .907 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 94.5 (121/128) | 89.7 (26/29) | 96.0 (95/99) | .189 |

| Specificity (%) | 69.0 (29/42) | 80.0 (4/5) | 67.6 (25/37) | .572 |

| PPV (%) | 100 (121/121) | 100 (26/26) | 100 (95/95) | - |

| NPV (%) | 96.6 (28/29) | 100 (4/4) | 96.0 (24/25) | .684 |

Abbreviations: CNB: core needle biopsy; NPV, negative predictive value; PSM: propensity score matching; PPV, positive predictive value.

Table 3.

Univariate Analysis of Relevant Variables for Diagnostic Accuracy in GGNs.

| Variables | Ground-glass (n = 34) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Success (n = 30) |

Diagnostic Failure (n = 4) |

P value | |

| Age (years) | .562 | ||

| ≤60 | 12 | 1 | |

| >60 | 18 | 3 | |

| Gender | .606 | ||

| Male | 11 | 2 | |

| Female | 19 | 2 | |

| Smoking status | .837 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 1 | |

| No | 21 | 3 | |

| Chest surgery history | .508 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 0 | |

| No | 27 | 4 | |

| COPD/fibrosis | .900 | ||

| Yes | 14 | 2 | |

| No | 16 | 2 | |

| Pleural effusion | .595 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 0 | |

| No | 28 | 4 | |

| Lesion location | .943 | ||

| Upper lobe | 22 | 3 | |

| Middle lobe | 0 | 0 | |

| Lower lobe | 8 | 1 | |

| Chest wall thickness (mm) | .442 | ||

| ≤20 | 2 | 0 | |

| >20,≤30 | 7 | 0 | |

| >30 | 21 | 4 | |

| Lung parenchyma density in the trajectory path (HU) | .441 | ||

| ≤−800 | 16 | 3 | |

| >-800,≤-600 | 5 | 1 | |

| >−600 | 9 | 0 | |

| Lesion–pleura distance (mm) | .211 | ||

| 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| >0,≤10 | 5 | 2 | |

| >10 | 16 | 2 | |

| Lesion size (along the puncture direction, mm) | .800 | ||

| ≤10 | 3 | 1 | |

| >10,≤20 | 18 | 2 | |

| >20,≤30 | 7 | 1 | |

| >30 | 2 | 0 | |

| Cavity | .377 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 0 | |

| No | 25 | 4 | |

| Lesion margin | .014 | ||

| Smooth | 11 | 2 | |

| Burred | 0 | 1 | |

| Spiculated | 19 | 1 | |

| Needle–pleura angle (°) | <.001 | ||

| ≤30 | 28 | 0 | |

| >30,≤60 | 2 | 2 | |

| >60,≤90 | 0 | 2 | |

| Traversing interlobar fissure | - | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 30 | 4 | |

| No. of sampling | .895 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| 2 | 26 | 4 | |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| >3 | 1 | 0 | |

| Patient position | .262 | ||

| Prone | 18 | 1 | |

| Supine | 5 | 2 | |

| Lateral | 7 | 1 | |

| Post-biopsy higher hemorrhage | .738 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 1 | |

| No | 20 | 3 | |

Abbreviation: GGNs: ground-glass nodules.

For post-biopsy complications, hemorrhage was the most frequent complication (Table 4). Grade 1 hemorrhage in GGNs occurred in 8 (23.5%) patients. Higher grade hemorrhage rate was 35.3% (12/34). The hemorrhage on post-procedural follow-up CT in ground-glass group was more frequently observed than that in solid group, but there is no statistically significant (P = .644) between two groups. Pneumothorax was found in 10 (29.4%) patients with GGNs by immediate follow-up CT scan. Among these patients, 5 (14.7%) were considered by grade 1 (1-10 mm), 4 (11.8%) grade 2 (11-20 mm), and 1 (2.9%) grade 3 (>20 mm). The occurrence of pneumothorax between ground-glass and solid groups was not significantly different (P = .302).

Table 4.

Complication Incidence of CT-Guided CNB of Pulmonary Ground-Glass and Solid Nodules after PSM.

| All | Ground-glass (n = 34) | Solid (n = 136) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhage | 94 (55.3) | 20 (58.8) | 74 (54.4) | .644 |

| Grade 1 | 33 (19.4) | 8 (23.5) | 25 (18.4) | |

| Grade 2 | 30 (17.6) | 7 (20.6) | 23 (16.9) | |

| Grade 3 | 26 (15.3) | 5 (14.7) | 21 (15.4) | |

| Pneumothorax | 63 (37.1) | 10 (29.4) | 53 (39.0) | .302 |

| Grade 1 | 37 (21.8) | 5 (14.7) | 32 (23.5) | |

| Grade 2 | 12 (7.1) | 4 (11.8) | 8 (5.9) | |

| Grade 3 | 14 (8.2) | 1 (2.9) | 13 (9.6) |

Abbreviations: CNB: core needle biopsy; PSM: propensity score matching.

There was no significant relevant factor in higher grade hemorrhage rate of ground-glass group. And we found that chest wall thickness, No. of sampling, and post-biopsy hemorrhage influenced the occurrence of pneumothorax in GGNs (P < .05) (Table 5). Only age showed a significant increase in higher grade hemorrhage rate of solid group (P = .042). Comparing the solid group patients with versus those without pneumothorax, gender, smoking status, COPD/fibrosis history, pleural effusion, chest wall thickness, lesion size, traversing interlobar fissure, patient position and post-biopsy hemorrhage were statistically significant (P < .05) (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 5.

Univariate Analysis of Relevant Variables for Complication Incidence in GGNs.

| Variables | Ground-glass (n = 34) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Higher grade hemorrhage (%) | P value | n | Pneumothorax (%) | P value | |

| Age (years) | .363 | .891 | ||||

| ≤60 | 3 | 23.1 (3/13) | 4 | 30.8 (4/13) | ||

| >60 | 8 | 38.1 (8/21) | 6 | 28.6 (6/21) | ||

| Gender | .549 | .362 | ||||

| Male | 5 | 38.5 (5/13) | 5 | 38.5 (5/13) | ||

| Female | 6 | 28.6 (6/21) | 5 | 23.8 (5/21) | ||

| Smoking status | .538 | .961 | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 40.0 (4/10) | 3 | 30.0 (3/10) | ||

| No | 7 | 29.2 (7/24) | 7 | 29.2 (7/24) | ||

| Chest surgery history | .183 | .876 | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 66.7 (2/3) | 1 | 33.3 (1/3) | ||

| No | 9 | 2.7 (9/31) | 9 | 29.0 (9/31) | ||

| COPD/fibrosis | .897 | .824 | ||||

| Yes | 5 | 31.3 (5/16) | 5 | 31.3 (5/16) | ||

| No | 6 | 33.3 (6/18) | 5 | 27.8 (5/18) | ||

| Pleural effusion | .313 | - | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 (0/2) | 0 | 0 (0/2) | ||

| No | 11 | 34.3 (11/32) | 10 | 31.3 (10/32) | ||

| Lesion location | .449 | .763 | ||||

| Upper lobe | 9 | 36.0 (9/25) | 7 | 28.0 (7/25) | ||

| Middle lobe | 0 | 0 (0/0) | 0 | 0 (0/0) | ||

| Lower lobe | 2 | 22.2 (2/9) | 3 | 33.3 (3/9) | ||

| Chest wall thickness (mm) | .847 | .014 | ||||

| ≤20 | 1 | 50.0 (1/2) | 1 | 50.0 (1/2) | ||

| >20,≤30 | 2 | 28.6 (2/7) | 5 | 71.4 (5/7) | ||

| >30 | 8 | 32.0 (8/25) | 4 | 16.0 (4/25) | ||

| Lung parenchyma density in the trajectory path (HU) | .936 | .936 | ||||

| ≤−800 | 6 | 31.6 (6/19) | 6 | 31.6 (6/19) | ||

| >−800,≤−600 | 2 | 33.3 (2/6) | 2 | 33.3 (2/6) | ||

| >−600 | 0 | 0 (0/0) | 0 | 0 (0/0) | ||

| Lesion–pleura distance (mm) | .497 | .835 | ||||

| 0 | 3 | 33.3 (3/9) | 2 | 22.2 (2/9) | ||

| >0,≤10 | 1 | 14.3 (1/7) | 2 | 28.6 (2/7) | ||

| >10 | 7 | 38.9 (7/18) | 6 | 33.3 (6/18) | ||

| Lesion size (along the puncture direction, mm) | .231 | .604 | ||||

| ≤10 | 3 | 75.0 (3/4) | 1 | 25.0 (1/4) | ||

| >10,≤20 | 5 | 25.0 (5/20) | 7 | 35.0 (7/20) | ||

| >20,≤30 | 2 | 25.0 (2/8) | 1 | 12.5 (1/8) | ||

| >30 | 1 | 50.0 (1/2) | 1 | 50.0 (1/2) | ||

| Cavity | .523 | .574 | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 20.0 (1/5) | 2 | 40.0 (2/5) | ||

| No | 10 | 34.5 (10/29) | 8 | 27.6 (8/29) | ||

| Lesion margin | .099 | .616 | ||||

| Smooth | 6 | 46.2 (6/13) | 3 | 23.1 (3/13) | ||

| Burred | 1 | 100 (1/1) | 0 | 0 (0/1) | ||

| Spiculated | 4 | 20.0 (4/20) | 7 | 35.0 (7/20) | ||

| Needle–pleura angle (°) | .365 | .450 | ||||

| ≤30 | 0 | 0 (0/0) | 0 | 0 (0/0) | ||

| >30,≤60 | 1 | 16.7 (1/6) | 1 | 16.7 (1/6) | ||

| >60,≤90 | 10 | 35.7 (10/28) | 9 | 32.1 (9/28) | ||

| Traversing interlobar fissure | - | - | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 (0/0) | 0 | 0 (0/0) | ||

| No | 11 | 32.4 (11/34) | 10 | 29.4 (10/34) | ||

| No. of sampling | .538 | .012 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 (0/2) | 2 | 100 (2/2) | ||

| 2 | 11 | 36.7 (11/30) | 6 | 20.0 (6/30) | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 (0/1) | 1 | 100 (1/1) | ||

| >3 | 0 | 0 (0/1) | 1 | 100 (1/1) | ||

| Patient position | .447 | |||||

| Prone | 7 | 36.8 (7/19) | 4 | 21.1 (4/19) | ||

| Supine | 2 | 28.6 (2/7) | 2 | 28.6 (2/7) | ||

| Lateral | 1 | 12.5 (1/8) | 4 | 50.0 (4/8) | ||

| Post-biopsy higher hemorrhage | .009 | |||||

| Yes | - | 0 | 0 (0/12) | |||

| No | - | 10 | 41.2 (10/24) | |||

Abbreviaiton: GGNs: ground-glass nodules.

Table 6 showed that the size/proportion of consolidation of GGN was not associated with diagnostic accuracy and complication incidence in CT-guided CNB (P > .05). The diagnostic accuracy, hemorrhage and pneumothorax rates according to the consolidation size were 90.1%, 31.8%, and 18.2%, respectively, for size≤10 mm; 88.9%, 22.2%, and 33.3%, respectively, for size between 10 mm and 20 mm; 100%, 16.7%, and 50.0%, respectively, for size between 20 mm and 30 mm; and 100%, 100%, and 0%, respectively, for size>30 mm. The diagnostic accuracy, hemorrhage and pneumothorax rates according to the proportion of consolidation were 100.0%, 33.3%, and 0, respectively, for solid proportion ≤25%; 93.3%, 60.0%, and 20.0%, respectively, for solid proportion between 25% and 50%; 81.8%, 45.5%, and 45.5%, respectively, for solid proportion between 50% and 75%; and 100.0%, 50.0%, and 20.0%, respectively, for solid proportion >75%.

Table 6.

Comparison of Diagnostic Accuracy and Complication Incidence in GGNs With Different Size/Proportion of Consolidation.

| n | Diagnostic accuracy (%) | P value | Higher grade hemorrhage (%) | P value | Pneumothorax (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consolidation size (mm) | .831 | .146 | .324 | ||||

| ≤10 | 22 | 90.1 (20/22) | 31.8 (7/22) | 18.2 (4/22) | |||

| >10,≤20 | 9 | 88.9 (8/9) | 22.2 (2/9) | 33.3 (3/9) | |||

| >20,≤30 | 6 | 100 (6/6) | 16.7 (1/6) | 50.0 (3/6) | |||

| >30 | 2 | 100 (2/2) | 100 (2/2) | 0 (0/2) | |||

| Proportion of consolidation(%) | .422 | .239 | .294 | ||||

| ≤25 | 3 | 100 (3/3) | 33.3 (1/3) | 0 (0/3) | |||

| >25,≤50 | 15 | 93.3 (14/15) | 33.3 (5/15) | 20.0 (3/15) | |||

| >50,≤75 | 11 | 81.8 (9/11) | 9.1 (1/11) | 45.5 (5/11) | |||

| >75 | 10 | 100 (10/10) | 50.0 (5/10) | 20.0 (2/10) |

Abbreviation: GGNs: ground-glass nodules.

Discussion

PSM is an advanced statistical tool designed to reduce the potential selection bias commonly seen in retrospective studies. 8 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first assessment of the diagnostic accuracy and complications incidence of CT-guided CNB of GGNs and solid nodules lesions based on PSM method. We found that there was no significant difference of CT-guided CNB between ground-glass and solid pulmonary nodules on diagnostic accuracy and complication rates.

CT-guided CNB in our study was shown to be a relatively safe and accurate method for establishing the diagnosis of pulmonary GGN. The diagnostic sensitivity was a little lower for GGNs than solid nodules. It might be due to the lower cellularity of GGNs. 6

In agreement with previously published studies,9,10 we showed that pulmonary hemorrhage was the most post-procedural unfavorable event. The hemorrhage complication rate in our study was 58.8% in GGN, which was above the reported range. 10 The reason of high hemorrhage rate was likely that we classified it into three grades, accounting for all GGN patients with hemorrhage along needle track on follow-up CT scan, regardless of symptoms, which was defined as grade 1. Grade 1 hemorrhage is often expected from our prior experience. Thus, we considered hemorrhage of grades 2 and 3 as higher grade (around 35.3%) and analyzed the related risk factors. The second most common complication of needle biopsy for GGN was pneumothorax (29.4%), which was self-limiting and resolved spontaneously. The rates of pneumothorax in the literature varied widely, ranging from 15% to 50%, 11 regardless of the nodule nature.

Because of a small No. of diagnostic failures, our results showed that lesion margin and needle–pleura angle were significant risk factors related to the diagnostic accuracy of GGNs. A meta-analysis has reported that diagnostic yield is dependent on size and location of the lesion. 12 Several previous studies12–14 classified lesions into 2 or 3 groups by different size but without statistical significance. Hiraki et al. 7 reported lesions ≤1 cm or ≥3.1 cm as an independent factor for diagnostic failure. They explained that smaller lesions posed technical difficulty while the larger was often associated with a higher necrosis rate. Our study classified lesions into 4 groups by size (eg <10 mm, 10-20 mm, 20-30 mm, and >30 mm) and observed no statistical significance, whether in GGN or solid group. However, we measured the lesion size along the puncture direction, which might be more believable than length in any direction. We also found the biopsy failure cases frequently occurred in lesions far from pleura in our study, probably due to technical difficulties. Notably, Hiraki et al. 7 and Portela et al. 15 showed that lower lobe nodule location was an independent predictor of biopsy failure. Lesions located in the lower lobes are more likely to be affected by respiratory motion due to the proximity to the diaphragm. Thus, the procedure is more technically challenging, depending on the operators’ experience. Most lesions in our cohort were located in the upper lobes.

In terms of our analysis of relevant variables for higher grade hemorrhage, there was no significant factor. Prior studies5,13 indicated that post-biopsy hemorrhage was often occurred when the targeted lesion was smaller or the trans-pulmonary needle pathway length was longer. The deeper the lesion location is, the more difficult accurate targeting of the needle is, with increased chances of small vessels damaged, especially GGO. The smaller the lesion diameter is, the more possibly the location changes with respiratory motion.

Several studies observed that the length of needle pathway was associated with pneumothorax. 10 Our result showed that the pneumothorax rate decreased when lesions attached pleura, which is in agreement with prior studies.16,17 Small lesions were reportedly associated with a higher risk of pneumothorax.5,18 Smaller lesions or lesions that further away from pleura need more time of location, therefore, more likely to develop procedural complications. Previous reports confirmed that emphysema represented a risk factor for pneumothorax development.5,10 We found that lung parenchyma density in the trajectory path above −600 HU was associated with less pneumothorax, especially in GGN group, similar to a previous quantitative study on emphysema. 19 Traversing interlobar fissure was found to be significantly related to pneumothorax in solid group (P < .05). This could be explained by the transgression of many pleural surfaces by the biopsy needle. 20 Previous literature indicated that when the targeted lesion located in the upper or middle lobe, major pneumothorax rate was often higher due to more punctures through fissure. 21 Hence, the operators should avoid traversing fissure as far as possible.

Importantly, our study revealed post-biopsy hemorrhage was a protective factor for pneumothorax, consistent with a previous published study. 22 Researchers demonstrated 2 explanations, of one which is that alveolar space is filled with blood, preventing air from getting into it; another is that the presence of blood on the pleural surface promotes adhesion between visceral and parietal pleura.

In addition, for part-solid nodules, CTR were not significantly different in diagnostic accuracy and complication incidence in our study. However, there are few relevant researches and some conclusions were inconsistent.18,23,24 Therefore, it still required further large-scale clinical validation.

However, there are still some limitations in this study. First, it is a retrospective design based on cross-sectional data at a single center and is limited by patients who have already been selected to undergo biopsies. These may have affected the statistical power and weakened the research value. And the amount of GGNs is relatively small. Second, although the PSM method matched the ground-glass and solid groups for better comparisons, it actually reduced the No. of samples, possibly reducing the statistical power for detecting significant risk factors. Furthermore, as a statistical technique, PSM might have its own limitations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, based on PSM, we found that the diagnostic accuracy and safety of CT-guided CNB were comparable for ground-glass and solid nodules and the size/proportion of consolidation may be not a relevant risk factor. The biopsy should avoid traversing interlobar fissure as far as possible. Smaller lesion size and deeper lesion location may lead to higher pneumothorax rate and post-biopsy hemorrhage may be a protective factor for pneumothorax.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tct-10.1177_15330338221085357 for Comparison of CT-Guided Core Needle Biopsy in Pulmonary Ground-Glass and Solid Nodules Based on Propensity Score Matching Analysis by Wenting An, Hanfei Zhang, Binchen Wang, Feiyang Zhong, Shan Wang and Meiyan Liao in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Abbreviations

- AAH

atypical adenomatous hyperplasia

- AIS

adenocarcinoma in situ

- CNB

core needle biopsy

- CTR

consolidation-to-tumor ratio

- FNA

fine needle aspiration

- LDCT

low-dose computed tomography

- MIA

minimally invasive adenocarcinoma

- NPV

negative predictive value

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- PPV

positive predictive value

- PSM

propensity score matching

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, China (Ethical number: 2021057). All cases collected in this study were patients who clinically required lung biopsy. And all patients signed the written informed consent before biopsy. This study is a retrospective study. Approved by the hospital, there is no need for written or verbal informed consent when collecting medical history records.

Author Contributions: WT A, HF Z, and MY L conceived and designed the study. WT A, HF Z, FY Z, BC W, and S W collected data. WT A, HF Z, FY Z, and BC W analyzed data and provided statistical recommendations. WT A and HF Z conducted literature search. WT A and HF Z generated the tables and figures. WT A and HF Z wrote the manuscript. MY L helped to critically review and comprehensive revise the manuscript. MY L supervised the research. All authors contributed to the research and approved the final version of this article.

ORCID iD: Meiyan Liao https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9515-6635

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Travis WD, Asamura H, Bankier AA, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer staging and prognostic factors committee and advisory board members. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for coding T categories for subsolid nodules and assessment of tumor size in part-solid tumors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(8):1204-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Network NCC. Lung Cancer Screening Version1.2022. NCCN.org, 2022. (Accessed Oct 26 2021, available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/lung_screening.pdf).

- 3.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Fu F, Wen Z, et al. Segment location and ground glass opacity ratio reliably predict node-negative Status in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109(4):1061-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei YH, Zhou FX, Li Y, et al. Extrapleural locating method in computed tomography-guided needle biopsies of 1,106 lung lesions. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10(5):1707-1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun S, Kang H, Park S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and complications of CT-guided core needle lung biopsy of solid and part-solid lesions. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1088):20170946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiraki T, Mimura H, Gobara H, et al. CT fluoroscopy-guided biopsy of 1,000 pulmonary lesions performed with 20-gauge coaxial cutting needles: diagnostic yield and risk factors for diagnostic failure. Chest. 2009;136(6):1612-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan CW, Liu JH, Wu RK, et al. Disordered sleep and myopia among adolescents: a propensity score matching analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2019;26(3):155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chassagnon G, Gregory J, Al Ahmar M, et al. Risk factors for hemoptysis complicating 17-18 gauge CT-guided transthoracic needle core biopsy: multivariate analysis of 249 procedures. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2017;23(5):347-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elshafee AS, Karch A, Ringe KI, et al. Complications of CT-guided lung biopsy with a non-coaxial semi-automated 18 gauge biopsy system: frequency, severity and risk factors. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heerink WJ, de Bock GH, de Jonge GJ, et al. Complication rates of CT-guided transthoracic lung biopsy: meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(1):138-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim TJ, Lee JH, Lee CT, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CT-guided core biopsy of ground-glass opacity pulmonary lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190(1):234-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarajlic V, Vesnic S, Udovicic-Gagula D, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and complication rates of percutaneous CT-guided coaxial needle biopsy of pulmonary lesions. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2021;27(4):553-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeow KM, Tsay PK, Cheung YC, et al. Factors affecting diagnostic accuracy of CT-guided coaxial cutting needle lung biopsy: retrospective analysis of 631 procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(5):581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portela de Oliveira E, Souza CA, Inacio JR, et al. Imaging-guided percutaneous biopsy of nodules ≤1 cm: study of diagnostic performance and risk factors associated With biopsy failure. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35(2):123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dommaraju S, Camacho A, Nakhaei M, et al. Dependent lesion positioning at CT-guided lung biopsy to reduce risk of pneumothorax. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(11):6369-6375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huo YR, Chan MV, Habib AR, et al. Pneumothorax rates in CT-guided lung biopsies: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors. Br J Radiol. 2020;93(1108):20190866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamagami T, Yoshimatsu R, Miura H, et al. Diagnostic performance of percutaneous lung biopsy using automated biopsy needles under CT-fluoroscopic guidance for ground-glass opacity lesions. Br J Radiol. 2013;86(1022):20120447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang HF, Liao MY, Zhu DY, et al. Lung radiodensity along the needle passage is a quantitative predictor of pneumothorax after CT-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy. Clin Radiol. 2018;73(3):319.e1-319.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozturk K, Soylu E, Gokalp G, et al. Risk factors of pneumothorax and chest tube placement after computed tomography-guided core needle biopsy of lung lesions: a single-centre experience with 822 biopsies. Pol J Radiol. 2018;83:e407-e414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan W, Guo X, Zhang J, et al. Lobar location of lesions in computed tomography-guided lung biopsy is correlated with major pneumothorax: a STROBE-compliant retrospective study with 1452 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(27):e16224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang HF, Zeng XT, Xing F, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of CT-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy and fine needle aspiration in pulmonary lesions: a meta-analysis. Clin Radiol. 2016;71(1):e1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SH, Chae EJ, Kim JE, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided aspiration and core biopsy of pulmonary nodules smaller than 1 cm: analysis of outcomes of 305 procedures from a tertiary referral center. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(5):964-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiranantawat N, McDermott S, Petranovic M, et al. Determining malignancy in CT guided fine needle aspirate biopsy of subsolid lung nodules: is core biopsy necessary? Eur J Radiol Open. 2019;6:175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tct-10.1177_15330338221085357 for Comparison of CT-Guided Core Needle Biopsy in Pulmonary Ground-Glass and Solid Nodules Based on Propensity Score Matching Analysis by Wenting An, Hanfei Zhang, Binchen Wang, Feiyang Zhong, Shan Wang and Meiyan Liao in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment