Abstract

Objective:

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is increasingly recognized as a common and impactful health determinant in homeless and precariously housed populations. We sought to describe the history of TBI in a precariously housed sample and evaluate how TBI was associated with the initial loss and lifetime duration of homelessness and precarious housing.

Method:

We characterized the prevalence, mechanisms, and sex difference of lifetime TBI in a precariously housed sample. We also examined the impact of TBI severity and timing on becoming and staying homeless or precariously housed; 285 precariously housed participants completed the Brain Injury Screening Questionnaire in addition to other health assessments.

Results:

A history of TBI was reported in 82.1% of the sample, with 64.6% reporting > 1 TBI, and 21.4% reporting a moderate or severe TBI. Assault was the most common mechanism of injury overall, and females reported significantly more traumatic brain injuries due to physical abuse than males (adjusted OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.14 to 1.39, P < 0.0001). The first moderate or severe TBI was significantly closer to the first experience of homelessness (b = 2.79, P = 0.003) and precarious housing (b = 2.69, P < 0.0001) than was the first mild TBI. In participants who received their first TBI prior to becoming homeless or precariously housed, traumatic brain injuries more proximal to the initial loss of stable housing were associated with a longer lifetime duration of homelessness (RR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.06, P < 0.0001) and precarious housing (RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.04, P < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

These findings demonstrate the high prevalence of TBI in this vulnerable population, and that aspects of TBI severity and timing are associated with the loss and lifetime duration of stable housing.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, homeless, precarious housing, marginally housed

Abstract

Objectif:

La lésion cérébrale traumatique (LCT) est de plus en plus reconnue comme étant un déterminant de la santé commun et percutant chez les populations itinérantes et précairement logées. Nous avons cherché à décrire les antécédents des lésions cérébrales traumatiques dans un échantillon au logement précaire et à évaluer de quelle façon la lésion cérébrale traumatique était associée à la perte initiale et à la durée de vie de l’itinérance et du logement précaire.

Méthodes:

Nous avons caractérisé la prévalence, les mécanismes, et la différence entre les sexes d’une lésion cérébrale traumatique de durée de vie dans un échantillon au logement précaire. Nous avons aussi examiné l’effet de la gravité et de la synchronisation d’une lésion cérébrale traumatique sur le fait de devenir et de rester itinérant ou d’avoir un logement précaire. Deux cent quatre-vingt-cinq participants au logement précaire ont rempli le Questionnaire de dépistage des lésions cérébrales (BISQ) en plus d’autres évaluations de santé.

Résultats:

Des antécédents de lésion cérébrale traumatique ont été rapportés chez 82,1% de l’échantillon, et 64,6% rapportaient > 1 LCT, tandis que 21,4% déclaraient une lésion cérébrale traumatique de modérée à grave. L’agression était le mécanisme le plus commun des blessures en général, et les femmes déclaraient significativement plus de lésions cérébrales traumatiques attribuables à l’abus physique que les hommes (RC ajusté 1,26; IC à 95% 1,14 à 1,39; p < 0,0001). La première lésion cérébrale traumatique modérée ou grave était significativement plus proche de la première expérience d’itinérance (b = 2,79, p = 0,003) et du logement précaire (b = 2,69, p < 0,0001) que ne l’était la première lésion cérébrale traumatique bénigne. Chez les participants qui ont subi leur première LCT avant de devenir itinérants ou en logement précaire, les lésions cérébrales traumatiques plus à proximité de la perte initiale de logement stable étaient associées à une durée d’itinérance plus longue à vie (RR = 1,04; IC à 95% 1,02 à 1,06; p < 0,0001) et au logement précaire (RR = 1,03; IC à 95% 1,01 à 1,04; p < 0,0001).

Conclusions:

Ces résultats démontrent que la prévalence des lésions cérébrales traumatiques est élevée dans cette population vulnérable, et que les aspects de la gravité et de la synchronisation des lésions cérébrales traumatiques sont associés à la perte de durée de vie d’un logement stable.

An estimated 200,000 people experience homelessness annually in Canada, with higher estimates worldwide. 1,2 Homeless individuals have higher rates of premature mortality, infectious diseases, and psychiatric illness than the general population. 1,3 Homeless and precariously housed youth and young adults may have differential risk factors and health outcomes and represent a uniquely vulnerable demographic within this marginalized population. 4,5 Although not formally homeless, individuals who live in precarious housing (e.g., shelters, single-room occupancy hotels, rooming houses) have comparable mortality, chronic health conditions, and unmet health care needs. 6,7

Over half of homeless and precariously housed individuals have a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI), and approximately one-fifth have a history of moderate or severe TBI. 8 TBI in this population is associated with poorer health (including self-reported physical and mental health, and suicidality) and functioning (including more memory concerns, increased health service use, and higher criminal justice system involvement). 8 Despite these concerning data, the association between TBI and becoming or remaining homeless or precariously housed remains largely unexplored.

Cursory examinations of the relationship between the timing of TBI and loss of stable housing indicate that the majority of individuals report receiving their first TBI prior to initially becoming homelessness. 9 –14 However, these studies have not considered whether the severity of TBI may be an important factor in the relationship between TBI and homelessness or precarious housing. Furthermore, no previous studies have evaluated the relationship between the timing of TBI and the lifetime duration of homelessness or precarious housing.

We characterized the lifetime history of TBI in homeless and precariously housed individuals and examined the relationship between the severity and temporality of TBI and the onset and duration of homelessness and precarious housing. As factors such as income loss, deterioration in medical and decision-making capacity, and decline in self-advocacy abilities can occur after more severe TBI, we hypothesized that more severe TBI will occur closer to the initial loss of stable housing. Additionally, as the stresses of unstable housing could negatively affect recovery from TBI, we hypothesized that TBI closer in time to the initial loss of stable housing would be associated with a longer duration of homelessness or precarious housing.

Method

Study Design and Participants

The Hotel Study is an ongoing prospective observational study of precariously housed individuals in Vancouver, Canada. Methodology and baseline characteristics have been reported previously. 4,15,16 Briefly, participants were enrolled between 2008 and 2017 from single-room occupancy hotels (precarious housing which often fails to meet Canadian minimum housing standards) 17 and the local downtown community court. Participants were eligible if they were aged 18 or older, proficient in English, and able provide written informed consent. Participants enrolled in the Hotel Study receive ongoing monthly follow-up interviews for up to 10 years (e.g., urine drug screens, general medical and symptom questionnaires, housing status), and yearly comprehensive neuropsychological and physician-administered neuropsychiatric examinations, which include detailed assessments of general and psychosocial functioning. The Hotel Study demographics are similar to other large Canadian studies working with homeless or precariously housed participants 18,19 (Supplementary Table 1) and to other studies on TBI in this population. 8

In this study, we report on a subsample of participants who had completed the Brain Injury Screening Questionnaire (BISQ) in the Hotel Study (n = 285). No additional inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied to participants from the broader Hotel Study. For descriptive analyses we evaluated older adults (age ≥ 30) and younger adults (age < 30) separately. 4 The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia and the Office of Research Ethics at Simon Fraser University.

Demographic and Housing Measures

Baseline sociodemographic data, housing history prior to study entry, and medical history profiles were collected by trained research assistants and study physicians using structured interviews at entry into the broader Hotel Study. Alterations in housing status were updated monthly. In the present study, homelessness was defined as living on the street; in shelters or vehicles; traveling or camping; having no fixed address; or couch surfing. Precarious housing was defined as living in a single-room occupancy hotel room, rooming house, or boarding house, according to the Canadian definition of precarious housing. 17 The lifetime duration of homelessness or precarious housing was defined as the total number of days of homelessness or precarious housing reported by participants from birth up to the date the BISQ was administered.

TBI Assessment

Lifetime history of TBI was assessed with Part I of the BISQ. 18 The BISQ is a structured TBI screening tool that has been employed in numerous settings, including in athletes, school children, medically ill cohorts, substance-using populations, and in other Canadian homeless populations. 20 Part I of the BISQ queries previous blows to the head across 19 specific situations, with detailed queuing intended to aid recall. 20 Establishing the validity of such self-report tools is inherently challenging given the lack of a reference standard. However, ascertaining TBI history through self-report may be superior to other methods (e.g., medical records), as a considerable proportion of individuals who sustain TBI do not seek medical care. 21 Similarly, less comprehensive self-report tools of TBI history, such as the Ohio State University TBI Questionnaire, have shown good reliability in populations such as prisoners and those with moderate or severe TBI. 22,23 We classified severity in accordance with the TBI severity definition of the World Health Organization. 24 Mild TBI was operationalized as any traumatically induced change in sensorium (including being knocked out, dazed, or confused) where the loss of consciousness (LOC) did not exceed 30 minutes. Moderate TBI was operationalized as traumatically induced LOC for between 30 minutes and 24 hours, and severe TBI as traumatically induced LOC for more than 24 hours. Mechanisms of injury were grouped into the categories of motor vehicle accidents or being struck as a pedestrian; falling or being struck by an object; sports and recreation; falling due to drug or alcohol blackout; being assaulted or mugged; and physical abuse.

Statistical Analysis

We compared demographic characteristics and TBI history variables between older and younger adults using independent-samples t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, Chi-squared tests with Yates continuity corrections, or Fisher Exact Tests as appropriate. All other analyses were conducted on the age-collapsed full sample. We evaluated sex differences across mechanism of TBI using logistic regression models with the mechanism as the dependent variable, adjusting for age. We used multiple linear regression models to evaluate the association between severity of worst lifetime TBI (no TBI, only mild TBI, or moderate-severe TBI) and the age at first homelessness or precarious housing, adjusted for sex. We used multiple linear regression models to evaluate the association between the first most severe TBI (i.e., the first mild TBI in those whose worst TBI was mild, or the first moderate-severe TBI in those whose worst TBI was moderate-severe) and the first experience of homelessness and precarious housing, adjusted for age and sex. Finally, we evaluated whether the number of years between the first TBI and the first experience of homelessness or precarious housing was associated with a longer lifetime duration of homelessness or precarious housing using negative binomial regression models, adjusted for age and sex. Negative binomial regression models were used as each dependent variable was a count (lifetime duration in days) and overdispersed. Exponentiating coefficients from the negative binomial regression resulted in rate ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed in R version 3.6.0. 25

Results

Our study sample consisted of 285 participants (older adult sample n = 226; younger adult sample n = 59; Table 1). The older adult sample had experienced a longer lifetime duration in precarious housing than the younger adult sample. When evaluated as a rate (lifetime duration divided by age) the younger adult sample had experienced a greater proportion of their lifetime spent in homelessness (U = 5,044.5, P = 0.005). Those in the younger adult sample became homeless and precariously housed at a significantly younger age than those in the older adult sample. At entry into the study, the younger adult sample had a higher prevalence of psychotic disorders, methamphetamine dependence, and cannabis dependence, while the older adult sample had a higher prevalence of opioid and cocaine dependence.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics for Participants, Further Stratified into the Older and Younger Adult Samples.

| Full Sample | Older Adults | Younger Adults | Test Statistic | P Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | N | Median | IQR | N | Median | IQR | N | Median | IQR | ||

| Age | 285 | 45 | 20 | 226 | 48 | 12.3 | 59 | 24 | 4 | N/Aa | N/A |

| Monthly income (CAD) | 280 | 758 | 395 | 224 | 766.5 | 429 | 56 | 820 | 410 | 5836 | 0.39 |

| Age at first homelessness | 211 | 23 | 15.5 | 158 | 27 | 17 | 53 | 19 | 4 | 1979 | <0.0001 |

| Age at first precarious housing | 266 | 29 | 18 | 209 | 34 | 16 | 57 | 21 | 3 | 1972.5 | <0.0001 |

| Months spent homeless | 283 | 18.2 | 52 | 224 | 17.5 | 58.1 | 59 | 19.3 | 40.4 | 6914.5 | 0.58 |

| Months spent in precarious housing | 266 | 48 | 92.3 | 209 | 68 | 102 | 57 | 14.2 | 30 | 2756.5 | <0.0001 |

| Demographic | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | Test Statistic | P Value | |||

| Female | 63/285 | 22.1 | 48/226 | 21.2 | 15/59 | 25.4 | 0.3 | 0.61 | |||

| Completed high school | 72/282 | 25.5 | 54/223 | 24.2 | 19/59 | 32.2 | 1.2 | 0.28 | |||

| Obtained General Educational Development | 43/282 | 15.2 | 41/223 | 18.4 | 2/59 | 3.39 | 7.0 | 0.008 | |||

| Obtained trade cert., diploma, or degree | 81/275 | 29.5 | 67/219 | 30.6 | 14/56 | 25 | 0.43 | 0.51 | |||

| Diagnoses at Study Entry | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | Test Statistic | P Value | |||

| Psychotic disorder | 135/285 | 47.4 | 100/226 | 44.2 | 35/59 | 59.3 | 4.2 | 0.041 | |||

| Mood disorder | 80/285 | 28.1 | 61/226 | 27 | 19/59 | 32.2 | 0.4 | 0.53 | |||

| Alcohol dependence | 53/285 | 18.6 | 39/226 | 17.3 | 14/59 | 23.7 | 0.9 | 0.34 | |||

| Methamphetamine dependence | 88/285 | 30.9 | 62/226 | 27.4 | 26/59 | 44.1 | 5.3 | 0.021 | |||

| Cocaine dependence | 160/285 | 56.1 | 156/226 | 69 | 4/59 | 6.78 | 71.1 | <0.0001 | |||

| Opioid dependence | 148/285 | 51.9 | 128/226 | 56.6 | 20/59 | 33.9 | 8.8 | 0.003 | |||

| Cannabis dependence | 109/285 | 38.2 | 70/226 | 31 | 39/59 | 66.1 | 23.0 | <0.0001 | |||

Note. Test statistics are for the difference in medians or proportions between the older and younger adult samples.

a As older and younger adults were classified based on age we did not compare age statistically.

Characteristics of Lifetime TBI

Characteristics of lifetime TBI are reported in Table 2. The median age at first TBI in the full sample was 12. The younger adult sample reported a significantly younger median age at first TBI (10 vs. 14, U = 3,802, P = 0.001), and a trend toward younger median age at first moderate or severe TBI than the older adult sample (18 vs. 25, U = 95, P = 0.06).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Lifetime History of TBI in the Full Sample, and Both the Older and Younger Adult Samples.

| Full Sample | Older Adults | Younger Adults | Test Statistics | P Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | ||||||

| Lifetime history of TBI | 234/285 | 82.1 | 187/226 | 82.7 | 47/59 | 79.7 | 0.1 | 0.72 | |||

| ≥ 1 Moderate TBI | 9/285 | 3.2 | 7/226 | 3.1 | 2/59 | 3.4 | 0.9 | > 0.99 | |||

| ≥ 1 Severe TBI | 56/285 | 19.6 | 50/226 | 22.1 | 6/59 | 10.2 | 3.5 | 0.061 | |||

| ≥ 1 Moderate or severe TBI | 62/285 | 21.8 | 54/226 | 23.9 | 8/59 | 13.6 | 2.4 | 0.13 | |||

| N | Median | IQR | N | Median | IQR | N | Median | IQR | Test Statistic | P Value | |

| Number of lifetime TBI | 285 | 3 | 4.0 | 226 | 3 | 4.0 | 59 | 3 | 3.5 | 6455 | 0.71 |

| Number of TBI per year | 285 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 226 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 59 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 8193.5 | 0.007 |

| Age at first TBI | 259 | 12 | 13.0 | 207 | 14 | 16.0 | 52 | 10 | 8.5 | 3802 | 0.001 |

| Age at first moderate or severe TBI | 56 | 25 | 15.3 | 49 | 25 | 18.0 | 7 | 18 | 1.5 | 95 | 0.06 |

Note. Test statistics are for the difference in medians or proportions between the older and younger adult samples. TBI = traumatic brain injury.

Eighty two percent of the study sample reported at least one lifetime TBI, and the proportion of older and younger adults who endorsed a history of TBI was not significantly different. The majority (64.6%) of participants reported more than one TBI in their lifetime and 59.6% of participants reported a TBI that resulted in LOC. The number of lifetime TBIs (median = 3) did not differ between the older and younger adults. In contrast, when analyzed as a rate (number of TBI per year), the younger adult sample reported a significantly higher number of TBI per year (U = 8,193.5, P = 0.007). In both older and younger adults, the lifetime duration of homelessness and precarious housing was not statistically significantly different between those with and without a history of TBI or between those with and without a history of moderate-severe TBI (effect sizes [r] all small [< 0.18], with Ps > 0.05). In this sample, 21.8% self-reported a moderate or severe TBI, with a higher, though not statistically significant, prevalence in the older adult sample (23.9% vs. 13.6%). Individuals whose worst TBI was moderate-severe also reported a higher number of lifetime TBIs (U = 3933, P = 0.002).

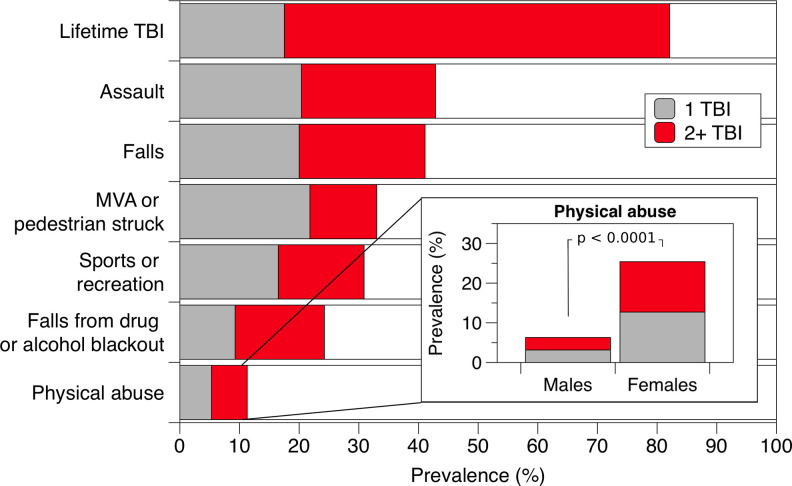

There were no significant differences in mechanism of TBI between the older and younger adult samples, so the two groups were collapsed (Figure 1). There was a trend toward a higher proportion of males reporting more TBI through assault than females (adjusted OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 0.99 to 1.31, P = 0.070). Females reported significantly more TBIs through physical abuse (Figure 1 inset; adjusted OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.14 to 1.39, P < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Lifetime prevalence of single and multiple traumatic brain injuries by mechanism. Note. The “Falls,” “MVA or pedestrian struck,” and “Sports and recreation” categories encompass multiple discrete mechanisms on the Brain Injury Screening Questionnaire.

Relationship between Severity of TBI and Losing Stable Housing

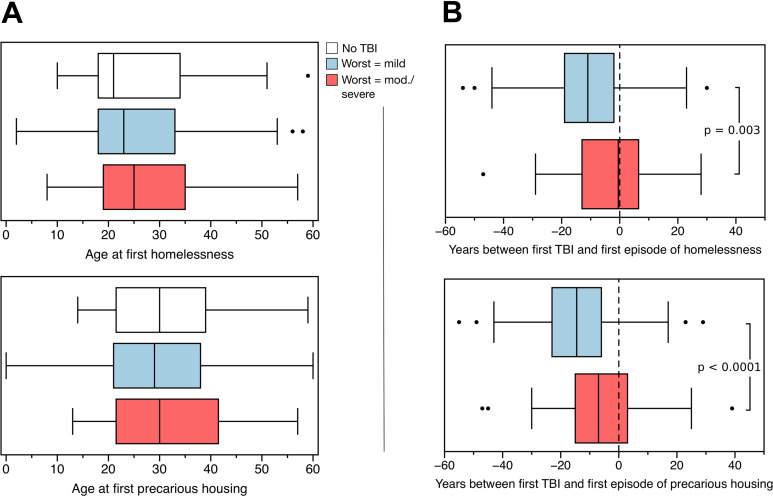

Age at first homelessness and precarious housing stratified by the severity of worst TBI is shown in Figure 2A. Neither mild TBI (b = −0.89, P = 0.85) nor moderate-severe TBI (b = −0.53, P = 0.79) were associated with an earlier age at first homelessness, as compared to those who did not report TBI, adjusted for age and sex. Findings were similar for age at first precarious housing (no TBI = reference; mild TBI: b = −2.15, P = 0.15; moderate-severe TBI: b = −2.03, P = 0.25), adjusted for age and sex.

Figure 2.

(A) Age at first homelessness and age at first precarious housing for the full sample who had no traumatic brain injury (TBI; white), whose worst TBI was mild (blue), and whose worst TBI was moderate or severe (red). (B) Difference in the number of years between the first mild TBI (blue) or the first moderate or severe TBI (red) and the first experience of homelessness and the first experience of precarious housing. Negative values denote a TBI occurring before the first experience of homelessness or precarious housing. Boxes represent interquartile range, whiskers denote 1.5 standard deviations, and dots represent outliers more than 1.5 standard deviations from the median.

We then evaluated the time interval between the participants’ most severe TBI and the onset of homelessness or precarious housing, adjusted for age. The number of years between the first most severe TBI and the onset of homelessness and precarious housing were similar between older and younger adults and the distributions for all participants are shown in Figure 2B. Among all participants, the first moderate-severe TBI occurred significantly closer to the year of first homelessness (b = 2.79, P = 0.003) than did mild, adjusted for age and sex. Similarly, we found that the first moderate-severe TBI occurred significantly closer to the year of first precarious housing (b = 2.69, P < 0.0001), adjusted for age and sex.

Relationship between the Timing of TBI and Lifetime Duration of Homelessness or Precariously Housing

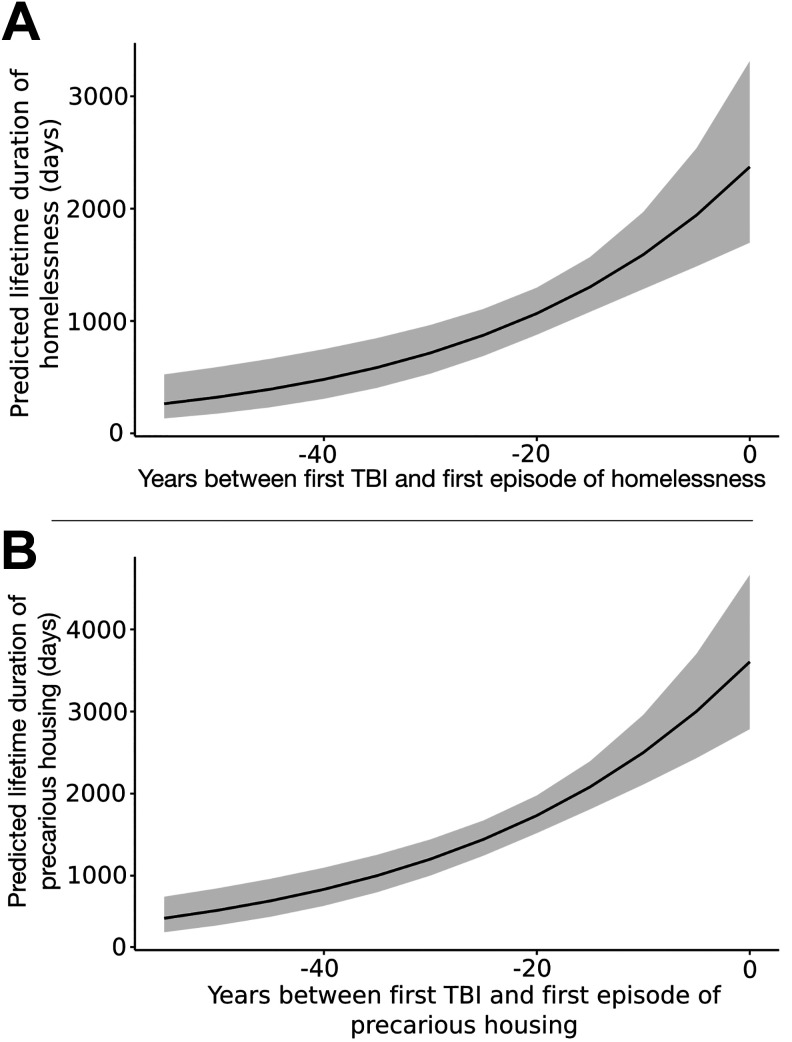

In this sample, 58.2% of participants reported that they received their first TBI prior to first becoming homeless, and 74.0% reported that they received their first TBI prior to becoming precariously housed. TBI closer in time to the first experience of homelessness was significantly associated with a longer lifetime duration of homelessness, adjusting for age and sex (RR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.06, P < 0.0001), Figure 3. The results were similar for the relationship between the first TBI and the first experience of precarious housing (RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.04, P < 0.0001), adjusted for age and sex.

Figure 3.

Predicted lifetime duration of homelessness (A) and precarious housing (B) as a function of the number of years between the first traumatic brain injury and the initial episode of either homelessness or precarious housing. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

We found a high burden of TBI in this sample as well as severity- and time-related associations between the onset and lifetime duration of homelessness and precarious housing. Our estimate of lifetime prevalence is nearly 30% higher than a recent meta-analytic estimate of the lifetime prevalence of TBI in this population, and our estimate of the lifetime prevalence of moderate-severe TBI is approximately in line with this recent estimate. 8 Consistent with the extant literature, our findings also indicate that the prevalence of any TBI, and of moderate-severe TBI, is considerably higher than estimates in the general population. 26,27

The ages at first TBI and first moderate-severe TBI in the older adult sample were similar to those reported in the general population 28 ; however, the ages at first TBI in the younger adult sample were lower than those in the general population. Younger adults also sustained more TBIs per year as compared with the older adult sample. TBI is also associated—in a dose–response relationship—with higher risk for low educational attainment, receiving disability pension, and welfare recipiency in adulthood. 28 This suggests that TBI may be an important factor in the broad range of challenges faced by homeless and precariously housed populations and that younger adults in this population may be differentially affected by TBI.

The most commonly reported mechanism of injury in this sample was assault, corroborating previous studies in this population. 9,14,29,30 Conversely, in the general population, sustaining TBI through assault is not a predominant cause of TBI. 31 Females had a significantly higher odds of sustaining TBI through physical abuse, an important and actionable finding that parallels recent studies that have evaluated TBI in individuals who are survivors of intimate partner violence. 32

Our findings also highlight associations between the severity and timing of TBI with housing status. First, moderate-severe TBI was closely related to the initial loss of stable housing, which suggests that a considerable proportion of newly homeless and precariously housed individuals may be experiencing sequelae attributable to TBI. This suggests that sequelae of TBI may be an important mediator of functional capacity in those who have transitioned into homelessness and may create additional barriers to exiting homelessness. Second, TBI closer to the initial loss of losing stable housing was associated with a longer lifetime duration of homelessness and precarious housing. Previous research on the relationship between having experienced a TBI and the duration of homelessness or precarious housing is mixed. Two studies (ns = 2,732 and 1,181) found TBI to be associated with a higher number of homeless episodes or a longer lifetime duration of homelessness, 11,33 while two studies (n = 111, and one on an overlapping sample, n = 283) found no relationship. 13,14 A number of reasons may explain why we found an association between unstable housing and the timing of TBI, but no association with lifetime prevalence of TBI. First, TBI is only one of many morbidities in this population, and others, such as addictions and psychosis, may overwhelm any signal from TBI. And second, survivorship bias is a consideration, where more severe TBIs may not be adequately represented because of death or disability that is so severe that some individuals are too impaired to maintain even precarious housing (e.g., requiring admission into long-term care). The relationship between TBI and homelessness is likely bidirectional given that homelessness is itself associated with a greater risk of incident TBIs, whether through an increase in violent encounters, substance abuse, or other factors. 34,35

Assessing lifetime TBI using the BISQ, a screening tool designed specifically to characterize lifetime TBI, is both a strength and limitation to our study. Many previous studies that have assessed TBI in homeless and precariously housed populations have used only a single question (i.e., “Have you ever experienced a blow to the head…”) to ascertain TBI history, yet, single-item screening questions for head injury have been shown to considerably underestimate the prevalence estimated by more comprehensive methods. 36,37 However, assessing TBI history with the BISQ still relies on participant self-report. Relying on self-reported alteration of consciousness is effectively the only way to retrospectively grade TBI severity, and yet, studies have shown substantial discrepancies between prospectively assessed alteration of consciousness and retrospective self-reported alteration of consciousness for the same injury. 38,39 Additionally, other factors such as the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder, cognitive impairment, and substance use have been suggested to moderate these discrepancies, 38 –40 but we did not evaluate these in the current study. Another limitation is that we were not able to identify the specific year of every injury after the first TBI, which precluded a more detailed analysis. For these reasons, and because of the retrospective nature of this work, no causal conclusions should be drawn from this study.

There are, however, implications for both frontline workers and policymakers. Our work expands on previous TBI research in this population and characterizes the burden of TBI in unstably housed young adults, a potential priority target for early intervention. Further, the association between TBI and the initial loss of stable housing may indicate that some individuals who are newly homeless or precariously housed may have recently suffered or are continuing to suffer health or functioning-related sequelae related to brain injury. Finally, our findings suggest that TBI may function as a barrier to exiting an unstable housing situation. Identification of persistent sequelae attributable to TBI in homeless and precariously housed individuals may help guide targeted care and be an important consideration when working to improve the health of this population. Future research that uses standardized assessment methods in prospective study designs is needed to better understand the full scope of the impact of TBI in this population.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437211000665 for Characterizing Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Association with Losing Stable Housing in a Community-based Sample : Caractérisation d’une lésion cérébrale traumatique et de son association avec la perte d’un logement stable dans un échantillon communautaire by Jacob L. Stubbs, Allen E. Thornton, Kristina M. Gicas, Tiffany A. O’Connor, Emily M. Livingston, Henri Y. Lu, Amiti K. Mehta, Donna J. Lang, Alexandra T. Vertinsky, Thalia S. Field, Manraj K. Heran, Olga Leonova, Charanveer S. Sahota, Tari Buchanan, Alasdair M. Barr, G. William MacEwan, Alexander Rauscher, William G. Honer and William J. Panenka in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

We thank the many research assistants and volunteers who are integral to this study.

Authors’ Note: Data cannot be made publicly available due to possible privacy breaches and other ethical and legal obligations to the study participants. These restrictions are outlined by the University of British Columbia’s Clinical Research Ethics Board and Simon Fraser University’s Research Ethics Board. Inquiries regarding data can be made to the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia and the study principal investigator (WGH).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Honer has received consulting fees or sat on paid advisory boards for: AlphaSights, Guidepoint, In Silico, Translational Life Sciences, Otsuka, Lundbeck, and Newron, and holds shares in Translational Life Sciences. Dr. Panenka is the founder and CEO of Translational Life Sciences, an early stage biotechnology company. He is also on the scientific advisory board of Flourish Lab. Both of these are early stage biotechnology enterprises with no relation to brain injury or vulnerable populations. The other authors have no competing financial interests.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CBG-101827, MOP-137103), and the British Columbia Mental Health and Substance Use Services (an Agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority) as well as the William and Ada Isabelle Steel Fund. WGH was supported by the Jack Bell Chair in Schizophrenia, AR is supported by Canada Research Chairs, and TSF is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

ORCID iDs: Thalia S. Field, MD, MHSc https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1176-0633

William J. Panenka, MD, MSc https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7143-6512

Supplemental Material: The supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaetz S, Donaldson J, Richter T, Gulliver T. The state of homelessness in Canada 2013. Toronto (ON): Canadian Homeless Research Network Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones A, Vila-Rodriguez F, Leonova O, et al. Mortality from treatable illnesses in marginally housed adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barbic SP, Jones AA, Woodward M, et al. Clinical and functional characteristics of young adults living in single room occupancy housing: preliminary findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Can J Public Health. 2018;109(2):204–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waclawik K, Jones AA, Barbic SP, et al. Cognitive impairment in marginally housed youth: Prevalence and risk factors. Frontiers Public Health. 2019;7(270):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Argintaru N, Chambers C, Gogosis E, et al. A cross-sectional observational study of unmet health needs among homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(577):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O’Campo PJ, Dunn JR. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339(b4036):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stubbs JL, Thornton AE, Sevick JM, et al. Traumatic brain injury in homeless and marginally housed individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e19–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barnes SM, Russell LM, Hostetter TA, Forster JE, Devore MD, Brenner LA. Characteristics of traumatic brain injuries sustained among veterans seeking homeless services. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(1):92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hwang SW, Colantonio A, Chiu S, et al. The effect of traumatic brain injury on the health of homeless people. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;179(8):779–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mackleprang JL, Harpin SB, Grubenhoff JA, Rivara FP. Adverse outcomes among homeless adolescents and young adults who report a history of traumatic brain injury. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(10):1986–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oddy M, Moir JF, Fortescue D, Chadwick S. The prevalence of traumatic brain injury in the homeless community in a UK city. Brain Inj. 2012;26(9):1058–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schmitt T, Thornton AE, Rawtaer I, et al. Traumatic brain injury in a community-based cohort of homeless and vulnerably housed individuals. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(23):3301–3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Topolovec-Vranic J, Ennis N, Howatt M, et al. Traumatic brain injury among men in an urban homeless shelter: observational study of rates and mechanisms of injury. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(2):E69–E76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Honer WG, Cervantes-Larios A, Jones AA, et al. The Hotel Study-clinical and health service effectiveness in a cohort of homeless or marginally housed persons. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(7):482–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vila-Rodriguez F, Panenka WJ, Lang DJ, et al. The Hotel Study: multimorbidity in a community sample living in marginal housing. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1413–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaetz S, Barr C, Friesen A, et al. Canadian definition of homelessness. Toronto (ON): Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stergiopoulos V, Hwang SW, Gozdzik A, et al. Effect of scattered-site housing using rent supplements and intensive case management on housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2015;313(9):905–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Palepu A, Gadermann A, Hubley A, et al. Substance use and access to health care and addiction treatment among homeless and vulnerably housed persons in three Canadian cities. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dams-O’Connor K, Cantor J, Brown M, Dijkers M, Spielman L, Gordon W. Screening for traumatic brain injury: findings and public health implications. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(6):479–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Setnik L, Bazarian JJ. The characteristics of patients who do not seek medical treatment for traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2007;21(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bogner J, Corrigan JD. Reliability and predictive validity of the Ohio State University TBI dentification method with prisoners. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(4):279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bogner JA, Whiteneck GG, MacDonald J, et al. Test-retest reliability of traumatic brain injury outcome measures: a traumatic brain injury model systems study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(5):E1–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Holm L, Kraus J, Coronado VG. WHO Collaborating Center Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Methodological issues and research recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehab Med. 2004;43(Suppl):113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corrigan JD, Yang J, Singichetti B, Manchester K, Bogner J. Lifetime prevalence of traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness. Injury Prev. 2018;24(6):396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frost RB, Farrer TJ, Primosch M, Hedges DW. Prevalence of traumatic brain injury in the general adult population: a meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40(3):154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sariaslan A, Sharp DJ, D’Onofrio BM, Larsson H, Fazel S. Long-term outcomes associated with traumatic brain injury in childhood and adolescence: a nationwide Swedish cohort study of a wide range of medical and social outcomes. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bymaster A, Chung J, Banke A, Choi HJ, Laird C. A pediatric profile of a homeless patient in San Jose, California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):582–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gargaro J, Gerber GJ, Nir P. Brain injury in persons with serious mental illness who have a history of chronic homelessness: could this impact how services are delivered? Can J Commun Ment Health. 2016;35(2):69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report to congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: Epidemiology and rehabilitation. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haag HL, Jones D, Joseph T, Colantonio A. Battered and brain injured: Traumatic brain injury among women survivors of intimate partner violence-a scoping review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. To MJ, O’Brien K, Palepu A, et al. Healthcare utilization, legal incidents, and victimization following traumatic brain injury in homeless and vulnerably housed individuals: a prospective cohort study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(4):270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nikoo M, Gadermann A, To MJ, Krausz M, Hwang SW, Palepu A. Incidence and associated risk factors of traumatic brain injury in a cohort of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in 3 Canadian cities. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(4):E19–E26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Svoboda T, Ramsay JT. High rates of head injury among homeless and low-income housed men: a retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(7):571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diamond PM, Harzke AJ, Magaletta PR, Cummins AG, Frankowski R. Screening for traumatic brain injury in an offender sample: a first look at the reliability and validity of the Traumatic Brain Injury Questionnaire. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(6):330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Russell LM, Devore MD, Barnes SM, et al. Challenges associated with screening for traumatic brain injury among us veterans seeking homeless services. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(S2):S211–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sherer M, Sander AM, Maestas KL, Pastorek NJ, Nick TG, Li J. Accuracy of self-reported length of coma and posttraumatic amnesia in persons with medically verified traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(4):652–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roberts CM, Spitz G, Ponsford JL. Comparing prospectively recorded posttraumatic amnesia duration with retrospective accounts. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31(2):E71–E77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mayou R, Black J, Bryant B. Unconsciousness, amneisa, and psychaitric symptoms following road traffic accident injuries. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(6):540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437211000665 for Characterizing Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Association with Losing Stable Housing in a Community-based Sample : Caractérisation d’une lésion cérébrale traumatique et de son association avec la perte d’un logement stable dans un échantillon communautaire by Jacob L. Stubbs, Allen E. Thornton, Kristina M. Gicas, Tiffany A. O’Connor, Emily M. Livingston, Henri Y. Lu, Amiti K. Mehta, Donna J. Lang, Alexandra T. Vertinsky, Thalia S. Field, Manraj K. Heran, Olga Leonova, Charanveer S. Sahota, Tari Buchanan, Alasdair M. Barr, G. William MacEwan, Alexander Rauscher, William G. Honer and William J. Panenka in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry