Abstract

Context

Work-family guilt has been reported among athletic trainers (ATs) working in the intercollegiate setting; however, it has yet to be fully explored from a descriptive, in-depth perspective.

Objective

To better understand the experiences of work-family conflict and guilt of intercollegiate ATs who are parents.

Design

Descriptive qualitative study.

Setting

Intercollegiate athletics.

Patients or Other Participants

Twelve collegiate ATs (females = 6, males = 6) participated in the study. All 12 were married (12 ± 7 years) with an average 2 ± 1 children (range = 1–4). The ATs reported working 51 ± 9 hours per week and spending 11 ± 7 hours per week on household duties or chores.

Data Collection and Analysis

One-on-one interviews were conducted with all participants. An inductive descriptive coding process was used to analyze the data after saturation was met. Peer review and researcher triangulation were completed.

Results

Conflict and guilt were discussed as unavoidable given the equally demanding roles of AT and parent. The resulting guilt was bidirectional, as each role is equally important to the AT. The management theme was specifically defined by 3 subthemes: creating a separation between work and parenting roles, the benefits of having a supportive workplace, and the importance of having coworkers and supervisors with shared life experiences.

Conclusions

The ATs experienced work-family conflict and feelings of guilt from their parental responsibilities. The guilt described by the ATs was bidirectional, as they placed high value on both their parenting and athletic training roles. Guilt was balanced and managed by reducing the spillover from the parental role into work or work into time at home. By separating roles and having supportive workplace environments, including coworkers and supervisors who had similar life experiences, ATs felt they were better able to meet work and home demands.

Keywords: intercollegiate athletics, family values, professional identity, organizational support

Key Points

Athletic trainers (ATs) who were parents and working in the intercollegiate setting expressed feelings of guilt that were bidirectional, meaning that the time as an AT created guilt about not meeting personal expectations in individual personal lives and vice versa.

Feelings of guilt were minimized by separating their roles and relying on supportive workplace environments.

The collegiate ATs felt they were better able to meet the demands of their jobs than the demands of their personal lives.

Work-family conflict continues to be problematic for working professionals, especially athletic trainers (ATs) working in sport, as their primary job duties are service oriented and require direct human interaction.1–7 Work-family conflict has been described1–7 among ATs employed in the intercollegiate athletic setting, and although no differences are often noted, parents did report some challenges finding balance.4,7 The sport setting, regardless of the role assumed (eg, coach, AT, sports information specialist), increases the possibility of work-family conflict.8,9 This is due to the job requirements and expectations that are notoriously rooted in long hours and the need to be physically present (ie, “face time”9).2–5 In sport organizations, ATs' roles are unique as they must balance patient advocacy and care in a model that promotes winning at all costs. The AT who works in the sport setting must be able to commit time, energy, and resources that can be seen as incongruent with having time outside of work for tasks such as parenting or being involved in nonwork activities.1–7 Due to its characterization as demanding and arduous and the likelihood of work-family conflict resulting from employee expectations, the sport setting has been the primary focus of work-life balance research.1–7,10–12

As the understanding of the work-family interface has grown, appreciation for the multidimensionality of the relationship between family, life, and work roles has increased. Individuals such as the AT working in the intercollegiate setting are trying to balance multiple roles (ie, AT, mom, dad, spouse), which is inherently stressful, particularly as the demands and expectations of the sport industry are arduous (eg, heavy travel schedules, long hours). Until recently, much of the literature7,11,13 on work-family conflict, which was modestly defined as a divergence between one's life roles (work versus home) that are incompatible in some way due to time or demands, has focused on women.

Work-family conflict is well understood in the sport setting1–12 as the literature is robust, specifically in terms of the organizational factors that facilitate conflict. An emerging area of the work-life model is the individual factors that influence experiences of conflict: for example, the emotional response associated with choosing one role over another.14 Guilt is a negative emotional response that occurs when balancing work, family, and life roles results in an internal struggle.14–16 Although guilt was once thought to be a response affecting mostly women, growing evidence suggests that male and female ATs both experience work-family guilt.14 Moreover, ATs with children described significantly higher levels of guilt.15

Much of the literature examining the work-family framework in intercollegiate sport has involved women,7,9,11,13 but investigators5,8 have shifted to include men or both sexes. Experiences of work-family conflict do not discriminate between sexes, even though what precipitates work-family conflict, or how it is viewed or coped with, may vary.5,7,8,11,13 Historically, working women expressed more challenges in finding a balance between work and home life, as they often embodied traditional gender stereotypes or had mothering philosophies that stimulated feelings of guilt or both.17,18 However, male ATs also indicated the importance of finding work-life balance5,19,20 and recognized that working as an AT coupled with other personal roles can be challenging.

Eason et al15 examined work-family guilt and documented its occurrence in ATs. This study highlighted the occurrence of work-family guilt among ATs, yet it was descriptive and did not fully capture the causative factors of work-family guilt in this population. A self-reported emotion, guilt reflects a negative emotional response when a person believes he or she has violated a moral or societal norm.14,21 Guilt is a perception based on and rooted in the individual's preferences and values and manifests when the person believes that his or her own behavior violates a self-guided goal, belief, or standard and creates a hyperintense focus on the consequences of the behavior.21 Work-family guilt is a specific emotional response that can result when individuals believe their work or personal life roles interfere with the ability to “perform” to their own standard in either of these roles.21–23 Work-family guilt, like work-family conflict, can be bidirectional. The work role can interfere with home life (ie, practice is scheduled into the evening hours, and the parent misses dinner and putting the children to bed), called work-family interference.21,22 It is also possible for guilt to stem from family roles that interfere with work obligations (ie, a child is sick and the parent misses practice).

Guilt is a topic that has emerged in the literature7,17,23 from examining the transition into parenthood. It has often been linked to mothers who report a reaction to their experiences of work-family conflict as one that causes distress; they feel as though they must prioritize one role (usually work) over another (usually home).7,17,23 Although feelings of guilt have been described as gender-role conflict, parenthood increased work-family conflict, as well as anxiety, as it pertained to juggling life roles.

Athletic trainers with children displayed more work-family guilt (guilt stemming from work interfering with family and guilt stemming from family interfering with work) than ATs without children.15 The ATs who were parents reported concerns about balancing work and life responsibilities and recognized the strain created by trying to find the time and energy to both parent and be an AT.2,4,7,17,19,20

A personal response that reflects an individual's choice to spend time or energy in one life role over another warrants an in-depth exploration, particularly from a qualitative framework. Work-family guilt is a sequela of work-family conflict14,15 and a negative emotional response that is individualized based on a person's family values, professional identity, and work-life balance philosophy. Thus, the purpose of our study was to gather rich descriptions of work-family conflict and guilt from collegiate ATs who were balancing their full-time athletic training positions and parenting roles. Specifically, our work was guided by the following research questions: (1) Did ATs who were parents experience feelings of work-family guilt? (2) If participants expressed feelings of guilt, did parenthood influence perceptions of work-family balance or feelings of guilt? (3) Have ATs who were parents developed any strategies to balance their roles as parents and full-time ATs?

METHODS

Research Design

We used a qualitative descriptive approach,24 which was a fitting way to accurately represent the lived experiences of collegiate ATs who were parents. Descriptive research studies borrow the underlying principles of a phenomenologic study but also seek to fully describe the participants' experiences as they lived a specific phenomenon. The goal of our study was to provide a rich description of ATs' experiences related to work-family conflict and guilt; therefore, the qualitative descriptive design provided the best framework for doing so.24,25 The descriptive design allowed us as researchers to summarize the experiences of our participants in a way that was attentive and allowed the participants to directly share their perspectives.26,27

Participants

We used a purposive sampling process to describe the experiences of collegiate ATs who were parents. The following criteria were used to actively recruit our participants: (1) employment in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) intercollegiate setting, (2) a full-time position that included at least 50% patient care duties, and (3) having at least 1 child. Work-family conflict has not been reported as varying among the NCAA Divisions; hence, we did not ask participants to supply this information as part of the demographic data.1,13 To ensure privacy and confidentiality, we replaced the name of each participant with a pseudonym.

In total, 12 collegiate ATs (females = 6, males = 6) participated in the study. Data saturation was met.

Personal Background

Our participants were 39 ± 7 years old. All 12 ATs were married (12 ± 7 years) with 2 ± 1 children (range = 1–4) whose ages ranged from 1 to 16 years (mean = 6 ± 4 years). The spouses of all but 1 AT worked full time. Our participants reported spending 11 ± 7 hours per week on household duties or chores (eg, laundry, cooking, cleaning, and caring for their homes).

Professional Background

All respondents were employed in the NCAA collegiate setting. They had been certified for 17 ± 7 years (range = 8–29 years) and described working 51 ± 9 hours per week. Two participants worked directly and only with football. The remainder shared coverage of a variety of sports with the sports medicine staff or worked with multiple sports depending on the season (or both). The participants represented 6 National Athletic Trainers' Association districts and 12 colleges or universities. The Table presents the data for each individual.

Table.

Participants' Demographic Data

| Participant Name |

Sex |

Age, y |

Experience as an Athletic Trainer, y |

Years Married |

No. of Children |

Age(s) of Children, y |

| Anna | F | 44 | 19 | 8 | 2 | 2, 6 |

| Beth | F | 43 | 20 | 12.5 | 1 | 10 |

| Cassie | F | 34 | 12 | 0.5 | 2 | <1, 2 |

| Ethan | M | 47 | 25 | 24 | 2 | 13, 16 |

| Garrett | M | 49 | 25 | 19 | 2 | 13, 16 |

| Hank | M | 51 | 29 | 23 | 1 | 10 |

| Kelly | F | 32 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Matt | M | 33 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Nate | M | 39 | 19 | 13 | 4 | 2, 6, 6, 8 |

| Nicole | F | 33 | 12 | 6 | 2 | <1, 3 |

| Paula | F | 37 | 15 | 13 | 3 | 4, 6, 8 |

| Zach | M | 30 | 8 | 9 | 2 | <1, 4 |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

Interview Guide and Procedures

Questions for the individual interviews were developed based on the most relevant gender, work-family, and work-family guilt literature.2,7,11,15,16,19,20 Generally, the semistructured interview guide consisted of several parts: (a) discussion of work and family responsibilities; (b) discussion of conflicts stemming from managing the work and family roles; (c) emotions and feelings behind decision making surrounding the work and family roles; and (d) strategies used by the participants to manage work, family, and life roles. Although each person was asked the same set of questions, the semistructured nature allowed the interviewer to ask additional, probing questions to gain further details and descriptions when necessary. The semistructured interview protocol underpinned the descriptive research paradigm, as it stimulated a natural conversation with each respondent while adhering to the structure as guided by the literature and prescribed questions.

A peer review was conducted before data were collected and after securing institutional review board approval. The peer, who was a published author in the work-life interface, examined the semistructured interview guide and provided feedback on its content and relevance to the study's purpose and aims. No changes to the content were made, but questions were reorganized to improve flow. Questions asked of the participants included the following:

“Can you describe your experiences with taking time off to attend to personal or family-related events/activities/obligations?”

“Where do you find support when balancing your parent role with athletic training duties?”

“Can you describe how you balance being a parent and an athletic trainer?” and

“Have you faced challenges being a parent and an athletic trainer in the college setting? If yes, describe why.”

The same researcher (K.M.R.) conducted all interviews, which lasted an average of 30 minutes, to promote consistency. An independent transcription company drafted the verbatim transcripts.

Data Analysis

We used an inductive descriptive coding process to analyze the data.24 The inductive process was guided specifically by the core concepts related to a descriptive, phenomenologic study that used data immersion as a key aspect of the coding.24 We read each transcript thoroughly to better understand the lived experiences of each participant. The goal of this initial reading was to become immersed in the data and gain a sense of what the person was experiencing while living the roles of parent and AT. After each subsequent reading of the transcript, the emergent findings visualized as “chunks” of data were highlighted by labels to categorize their meaning. The repeated readings of the transcripts led to the collapsing of categories into the most common themes to capture the experiences of our participants related to managing their lives as full-time ATs and parents. Once the most emergent themes were apparent, all categories were collapsed and data were extracted to support the final themes, as discussed in the Results section. These themes were also evaluated as they related to the research questions outlined previously.

Rigor

To demonstrate the quality of the results, we relied on purposeful sampling and data saturation to recruit participants who could provide rich descriptions of parenting, athletic training, and navigating work and life as a collegiate AT. Additional strategies to facilitate trustworthiness and dependability of the results were the reliance on a peer reviewer and researcher triangulation. Beyond the review of the semistructured interview guide, the peer provided feedback and confirmation of the analyses performed by 2 of the researchers. The peer reviewed 2 coded transcripts and an uncoded transcript along with operational definitions assigned to the final themes determined by the researcher triangulation. Researcher triangulation was satisfied via independent data analysis by 2 investigators (S.M.S., K.M.R.) who followed the same stepwise approach. The researchers, who possessed training in the selected analyses, discussed the process before and then shared their findings after completion. The process contained the same steps as outlined earlier; at its conclusion, the researchers agreed on the findings.

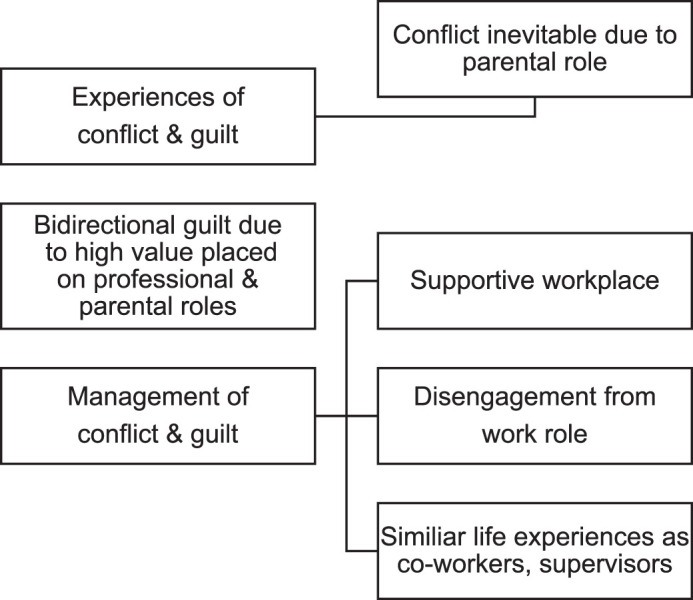

RESULTS

Our inductive descriptive analyses revealed 3 main themes. Conflict and guilt were discussed as unavoidable because the roles of AT and parent were equally demanding, and the guilt was bidirectional because each role was equally important to the AT. The management theme was specifically defined by 3 subthemes: creating a separation between work and parenting roles, the benefits of a supportive workplace, and the importance of coworkers and supervisors with shared life experiences. Each theme is fully described in the following sections with supporting quotes.

Conflict and Guilt Happen Due to the Parental Role

Our participants described feelings of conflict and guilt because they wanted to spend time, equally, in each life role. Of note, most of our participants had school-aged children; a few of those were in preschool or younger. Anna said about being a mom and an AT that, “It's the hardest [to balance those roles at the same time], the guilt is the hardest to deal with, because I always feel guilty, like I am short-changing someone.” Hank characterized the jobs of a dad and an AT as “24/7,” which “creates conflict regularly because you can't be in 2 places at once.” Garrett stated,

It's difficult in any profession, any job, to raise a family and work full time. I think it's an expectation to teach your children that it's important to have a career, obviously to have food and shelter and amenities that you would like as an educated, grown adult, that sacrifices have to be made for work and family time.

Kelly noted,

This [being a mom and collegiate AT] is so overwhelming. This is so hard to try to meet these previous expectations that I've provided of myself as a new mom and an athletic trainer.

Nicole attributed the “irregular schedule of college athletics” as the biggest challenge of being a mom and AT. Cassie described work-life balance struggles as a parent: “Unexpected things come up such as my kids gets [sic] sick.” Ethan cited the importance of being available for his kids, as well as his student-athletes. He recognized that at times, conflicts happened due to the nature of athletic training:

I just want to be there for my kids as much as possible. I'll do anything for them. But they also know that there's times that dad has to be at work, dad has to travel. And that conflicts with my wanting to be there. But they understand that I like helping people. I want to be my best for that.

Zach discussed the challenges of performing in both roles as well. He said,

… I struggle with, it's hard to be a bad ass at work and be a bad ass at home. And I think unfortunately that's probably how a lot of ATs are wired. That they want to do a good job and our strength is our weakness and the strength [is] that we want to take care of people. We want to go the extra mile for everybody: spreads us really, really thin, both at home and at work. So, I definitely find that a big difficulty.

Both women and men experienced conflict and guilt due to balancing their roles as parents and collegiate ATs, as each role is time intensive.

Guilt Is Bidirectional

Participants placed high value on their parental and professional roles, which was a catalyst for bidirectional feelings of guilt. Guilt, not conflict, was described as a negative emotional response when having to take time away from either their professional role as an AT or from their children and spouses. Anna articulated that she felt bidirectional guilt when she shared, “just the guilt you feel when you can't be there, at home or at work.” When asked about the challenges of being a mom and an AT, she remarked, “… the guilt is the hardest one to deal with.” She continued, “… I feel guilty because I feel like maybe I'm short-changing the student-athletes.” Anna also mentioned, “I would say the hardest thing about being a mom is just the guilt from being away from your children.” Regardless of the role assumed, an AT who was not performing or engaging in that role felt guilt.

Garrett acknowledged bidirectional guilt when reflecting on balancing his roles as a dad and AT:

You can feel guilty on certain things. It goes on both sides. I went to a wedding for close family friends, and I felt guilty leaving my baseball team, not being there. So yes, I would say I feel it in both directions, feel as a parent that I'm missing certain things because you can't make up the Saturday football game when your son or daughter has a sporting event themselves or a recital or anything like that. But you kind of pick and choose and be crafty with the schedule.

Garrett shared a strong personal identity as a dad—“It's the best job that you can have as well as probably one of the most difficult jobs that you can have”—as well as a strong professional identity: “I love what I do [as an AT]. I love not being in an office all the time. I love being involved with our sports programs. I love being viewed as a staff member.” Another father, Zach, also commented on bidirectional guilt when talking about balancing his roles as a dad and collegiate AT. Like Garrett, Zach's professional and personal identities were very meaningful to him. Of being a dad, he observed, “I think it's probably the most important job, I have.” Zach also viewed his AT role as “kind of like being a father, it is important, and I want to do a really good job.” When discussing how he balanced his roles of an AT and a father, Zach reflected,

I have a hard time balancing it all. There [are] just not enough hours in the day. I'm a person who is really … I'm not addicted to success, but I'm a person who really likes to be successful. And so, I definitely feel [it] when I'm not fulfilling with my role as a father or an athletic trainer, I feel like I'm failing at one or the other. I don't like to feel that way. There are times where I'm not connecting with my kids or I'm just not around enough and so they're not … they're either upset with me or whether it's vocalized or if it's just subconsciously, I'm just not on their level sometimes.

Nicole talked about the inherent challenges of balancing both roles as she, like our other respondents, saw both roles as important: “I have expectations of myself as a mom and similarly high expectations of myself as an athletic trainer.” Regarding navigating her roles, Nicole said, “You have that guilt as I need to be here and be the best version that I can be as a mother, and I need to be here and be the best version that I can be as an athletic trainer.”

Guilt is a negative emotional response that was described by our participants as occurring because they wanted to perform their roles at their highest level, even though they realized time was limited, and it was difficult to balance both roles.

Management of Conflict and Guilt

Our participants discussed 3 specific ways in which they were able to manage their work-family conflict and guilt: (1) employment in supportive workplaces, (2) separation from work roles when home, and (3) having coworkers and supervisors with similar family and life experiences.

Supportive Workplace

Respondents indicated that they were currently employed in a supportive work environment or in an environment in which their coworkers and supervisors understood their role as a parent. Ethan shared the philosophy at his college as, “It's always family first.” Paula felt her supervisor and her workplace were understanding of her parenting role in saying, “They absolutely are supportive.” She gave an example:

My son was sick a lot this winter. He got the flu twice, and then strep throat and each time my boss just said, stay home, take care of him, we'll take care of the rest of it. So, I think it's helpful to have a boss who understands that you have to care for your family and do your job. But there's also some components where the family's more important. But we can figure out ways to adapt and adjust as needed; in that way, we can do both things.

Paula continued with “My superiors enforce that they're okay with me missing stuff as needed and kind of doing that for myself and the pressure put on me [to take time away from my job].” Garrett's workplace was supportive of parenting by being “hands-off” regarding oversight of his management of the staff and athletic training facility:

I think my administration's ability to not micromanage how I operate my program, the expectations that we will provide a very high level of service, that I'm not closing the [athletic] training room because I don't want to miss a parent-teacher conference when the kids were younger, but if my assistant wants to go meet with their second-grade teacher and it's going to affect the schedule, myself and my staff will cover each other to make sure that those things can happen.

Hank attributed his ability to manage the parental role to his employer:

So, the employer's huge here. My boss, my head athletic trainer, is awesome. And even the rest of the staff is similar. And not all of them have kids yet. There's some young staff here, too, but even those guys kind of understand, like, you work the morning hours, you're dropping off the kid at the bus stop kind of thing. But I think having that setting here, it helps tremendously.

Having coworkers or head ATs who demonstrated compassion, understanding, and sympathy toward the demands of parenthood and athletic training was identified as helpful in balancing the roles and limiting the guilt that can occur.

Separation From the Work Role

Creating deliberate boundaries between work and home was discussed by our participants as a way to reduce the negative spillover and increase the enjoyment at home. Beth, when sharing her views on motherhood and her role as a mom, addressed the need to segregate her work from her home life and live in the moment. She said,

I have made a conscious effort to make sure when I am at work, I focus on work, and when I'm at home, I'm not as much, as it's easy to say, I'm focused on home trying to make sure if my son is awake and I'm home, I'm in the moment present in the moment with him, and there are definitely times where after he goes to bed I refocus back to work.

To balance parenthood and his job as an AT, Matt sought to maintain boundaries and leave work at work:

So I look at everything with that, and I certainly make sure I'm trying to dedicate as much possible time that I can for my family. When I come home on any given day, I will put my work phone … and that's another thing I do, I have a work phone, and I will keep my work phone in another room, or off, whatever it is for at least an hour to 3 hours so I could get [the] little guy to bed and spend time with my wife.

Hank discussed the idea of disengaging from work to enjoy his time with his son and refocus on work once the day is over, “when we have time together [usually at nighttime], I shut off the work. I turn off the phone kind of thing and get back to the athletes after he's in bed, kind of thing.” As for balancing his responsibilities and managing his time, Zach noted, “… I find myself not necessarily working any less hours at work but trying to make more hours count at home. Trying to stretch more time to do more things at home.” Focusing on one role while engaged in it was a way to reduce the guilt felt from not being present or available in the other.

Figure.

Athletic trainers' experiences with work-family conflict and guilt.

Similar Life Experiences

Support and understanding were present in the collegiate setting, but our participants recognized that when coworkers and supervisors had similar life experiences (eg, being married or having children), appreciation for the demands of both roles was greater. Matt indicated that his supervisor was a great role model and supportive of his parental role. He believed that was the case because the supervisor was also a dad: “He [my boss] does an amazing job [supporting me]. He's a father of 3 and he has been a great example and a great mentor to me of how to be a dad and athletic trainer.” Nate's supervisor also had children, which was helpful as Nate balanced his job and childrens' activities and needs: “The head [athletic] trainer [I work for] himself has 2 kids, and he'll bring his kids to work and understands that need to make it work. And our staff is kind of big, not huge, but to where we can kind of say, ‘Hey, can somebody do this while I go pick up my kid from daycare?' Or, ‘Can you do this because this came up?' ”

Cassie believed the collegiate setting was beneficial for her and provided a good environment for balancing her responsibilities at work and at home. She stated, “I think the college as a whole that I work at is very, very good for females and the leadership giving you your rights and your FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act]. All that is very good at this college.” Cassie illustrated that sharing life experiences with a coworker or supervisor was necessary to support parenting roles while working full time:

It just, I think it's hard when my supervisor that I work under directly, doesn't get it completely, as she doesn't quite understand because it's never happened to her [being a mom]. And she is compassionate and cares but at the same time she's got to run this.

Experiencing similar life stages or parenting roles was viewed as a helpful facilitator of balance and managing all the responsibilities that accompany parenthood and athletic training.

DISCUSSION

Work-family conflict and guilt were reported by our participants in part due to the demanding nature of being both a parent and an AT. Although the findings are not unexpected, the descriptions provided by our participants highlight the value placed on being a parent, as well as an AT, suggesting a high level of professional identity and strong family values. Moreover, our results suggest that guilt for the ATs in the collegiate setting, who saw both their life and work roles as very important, would likely experience guilt due to wanting to perform well in each. Although guilt was often evaluated and defined as bidirectional,14,15 most investigators reported a greater sense of guilt when ATs missed home or family activities compared with being absent from work. We observed that the guilt experienced by ATs was encountered in both their work and personal roles and also arose from their role as a parent.

These ATs had several coping strategies for managing their conflict and guilt but still recognized that they experienced these feelings. Shared experiences with coworkers was identified as helpful, as it created camaraderie as well as a support system. This idea of commiserating with others may have partially alleviated the guilt experienced by parents who were balancing demanding jobs.

Conflict and Guilt Happen Due to the Parental Role

Parenting and being an AT have a common thread: the demands of “24/7” jobs. Consistent with the literature1–7 on the workplace culture and expectations of the intercollegiate sport setting, our participants described being an AT alone as a full-time job; thus, coupling the parental role created conflict as well as guilt. These experiences of work-family conflict have been characterized.1–7 Inherently, conflict is assumed to increase once an individual becomes a parent. Our results, along with those of prior researchers,4,7,17,19,20 demonstrated that parenthood created challenges and was stressful when working full time. Although none of our participants directly attributed the age of their children to their experiences of guilt or conflict, it is possible that the generally young age of our participants' children was a factor. Earlier authors28,29 found that younger children, who required greater care from the parent, were linked with greater levels of parental conflict. Future investigators should explore in more depth the demands placed on a parent pertaining to life stage.

Our participants also described experiences of guilt because their positions required time and energy that often spilled over into their available time to be at home. Early examinations, mostly anecdotal, focused on guilt as a woman's concern (ie, “mom guilt”), but our results, much like the recent literature in athletic training,15,16 showcased that guilt may not have been a sex-based outcome. This was in contrast to the work of Kahanov et al,20 whose female ATs reported more guilt than did male ATs. As we continue to understand that men and women want work-life balance, guilt is likely to occur when they feel conflicted over having to choose the role in which to invest their time, energy, and resources. Although it may be easy to assume that the parental role contributes to feelings of guilt, our findings provided empirical evidence that the demands of being a parent were contributing to feelings of guilt.

Guilt Is Bidirectional

These ATs experienced guilt from the demands of being a parent and perceptions of missing out on family and parental responsibilities but also because they felt they were not meeting their own standards as an AT. This is a subtle, yet important, difference. Parents were not just experiencing emotions of guilt because they thought they were letting their families and children down; they also experienced guilt because they perceived that they were not meeting the expectations of their patients or their employers. In this context, guilt is described as a bidirectional construct that happens when an individual has to make a choice between work and family.14,22 It can be further explained as an incongruity between one's preferred and actual level of role participation at home or at work.22 Despite the indication that guilt can be bidirectional, researchers14,16 have largely focused on the guilt that arises from work interfering with home life. This mimics the data on work-family conflict, which mostly addressed how work interfered with family relationships. Our results showed that the guilt experienced by collegiate ATs who were parents manifested bidirectionally.

This bidirectional nature of guilt was likely a derivative of our participants holding an adaptive lifestyle mindset that encompassed both strong professional (ie, AT) and personal (ie, mom or dad) identities. An adaptive lifestyle allows for a balance of time spent working as well as at home.18 Many female ATs demonstrated this adaptive mindset, which was often a catalyst for conflict. The ATs perceived that they were performing less adequately in one role than another or that it was nearly impossible to give the same energy or time to the parental role when the AT role was so demanding.7,10,17,19,20 We are among the first to show that male ATs wanted a balance as well. They recognized that parenting was demanding and even more complex when serving as a collegiate AT. Eason et al16 found that both male and female secondary school ATs who were parents experienced guilt and that the guilt appeared to stem from work interfering with family. They focused on sociocultural factors that may contribute to the experiences of guilt for women but did not present data to support the bidirectionality of work-family guilt.16 This could have been due to secondary school ATs' identities resonating more with their families and, thus, their primary guilt manifested when they missed family obligations, but this possibility needs to be further explored.

Guilt can be characterized as 3 types: physical, emotional, and psychological.30 Based on these distinctions, our participants experienced physical guilt, or the inability to be physically present to attend to work, family, personal obligations, or other duties. They also mentioned the psychological spillover that came from missing these events. Future authors can further assess the types of guilt experienced by ATs in order to develop effective strategies to minimize the negative effect of missing out on work or family obligations.

Management of Conflict and Guilt

Work-family conflict and work-family guilt are often viewed as interrelated constructs. Therefore, strategies used to mitigate work-family conflict may also be helpful for minimizing feelings of guilt. Moreover, when trying to create work-life balance, multiple role management strategies are available. The benefits of a supportive work-family environment at home have been discussed.4,6,17,31 Supportive workplace environments demonstrate concern for the wellbeing of the employee through a variety of mechanisms. Our participants recognized coworkers or supervisors who demonstrated an empathetic and compassionate mindset for nonwork obligations; this finding was also reported by Eason et al16 among secondary school ATs. Those ATs, who were also parents, viewed their workplaces as supportive due to supervisors, administrators, and coworkers who acknowledged the demands parents faced when raising and caring for children while working. Despite feelings of guilt and conflict, our respondents recognized that they had organizational support, illustrating that organizational mechanisms may not minimize the guilt felt by a person, as it is an individual-level factor.7

Work-life separation has become a common recommendation in the work-life literature,5,6,10,11 as it helps the individual gain energy and enjoyment from one role without the negative spillover or influence of the other. Trying to simultaneously balance or multitask can lead to less satisfaction because the person cannot fully enjoy the benefits of engaging in all of those roles. Our ATs discussed creating boundaries around their family time, as well as their work obligations, focusing solely on one at a time. This strategy has been suggested previously6,10,11 as a means of reducing the negative effect of working in a demanding work environment, such as the intercollegiate setting.

Supervisors who advocate for and encourage personal and family time have been linked to lower levels of work-family conflict.31 Our participants identified supervisors who were supportive of their personal choices and appreciated the influence of parenthood, as they also had experience with raising families. Although shared life experiences may not be completely necessary for a supportive workplace, supervisors and coworkers should accept others' life choices and recognize that work-life balance is important for everyone. The ATs cited feelings of guilt for having to choose one role over another; if a supervisor or coworker can demonstrate empathy and understanding, the effect of the guilt can likely be lessened. An AT can advocate for and create a supportive workplace by serving as a mentor to peer ATs and coworkers and as a role model for healthy work-life balance practices. The AT can also use self-advocacy to ensure that personal and professional needs are met. Working in the intercollegiate setting has the potential for a supportive culture as previous authors4,6,11 have addressed teamwork, camaraderie, and job sharing as benefits of the setting as well as facilitators of a balanced lifestyle.

Our study adds to the literature from the perspective of role investment and how that can ultimately create the possibility of conflicts. Our participants were equally vested and placed high value on their roles as parents and ATs and, thus, experienced work-family conflict. In turn, this appeared to stimulate feelings of guilt as they often felt they had to choose between the roles. We recognize that not all ATs or parents have the same level of role investment or commitment, but it is important for the organization as well as the individuals themselves to be aware of this disposition. Simply put, recognizing the level of investment one has in various life roles can help the individual to better manage, prioritize, and invest time and energies as a means of reducing the negative spillover. Applications can be drawn from the concept of work commitment, which is measured on a spectrum of positive (ie, work engagement), where the employee is enthusiastic about the role,32 and negative (ie, workaholism), where the employee is overcommitted.33 Finding the right balance between being engaged and yet not overcommitted can be key to reducing the negative spillover. This can help with feelings of guilt, or in some cases, the purposeful neglect of non–work-related responsibilities or obligations.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

We selected a heterogeneous sample in regard to the level (ie, Divisions I, II, and III) of the collegiate respondents. Our focus was not to differentiate within the collegiate setting but rather to explore it holistically. Therefore, the findings reflect generalities of the collegiate setting rather than the specific nature of each level. Although researchers have not identified differences in work-family conflict experienced by ATs among the different collegiate levels, it is still important to explore the nuances of each level for a full understanding. Our study was exploratory, and our sample represented ATs with children of various ages rather than exploring the experiences of those with younger (ie, 6 years and under) versus middle-school–aged, secondary school–aged, or adult-aged children. Life stages of the children may affect experiences of conflict and guilt and thus should be further examined. Additionally, future investigators may assess experiences of conflict and guilt among ATs' spouses.

CONCLUSIONS

Athletic trainers who worked in the collegiate setting and were parents experienced work-family conflict and guilt due to the time demands of both roles. The conflict and guilt arose from the desire to be present and available to perform their jobs as well as to raise their children. Yet they felt as though there was not enough time to do both. Although guilt is often described as occurring from a spillover of work into home lives, our participants shared that they felt guilty when they were unable to be either at home parenting or at work providing care. Despite having support at home and in the workplace, our respondents recognized that conflict and guilt were inescapable. Relying on social support networks, including coworkers or supervisors with whom they shared life roles, was helpful in managing the conflict and guilt. Additionally, focusing on one role at a time, free of spillover, was useful in reducing feelings of conflict and guilt.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Eason CM. Experiences of work-life conflict for the athletic trainer employed outside the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I clinical setting. J Athl Train . 2015;50(7):748–759. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.4.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train . 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train . 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. ATs with children: finding balance in the collegiate practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Train . 2011;16(3):9–12. doi: 10.1123/ijatt.16.3.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Trisdale WA. Work-life balance perspectives of male NCAA Division I athletic trainers: strategies and antecedents. Athl Train Sports Health Care . 2015;7(2):50–62. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20150216-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train . 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.5.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM. Perceptions of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I female athletic trainers on motherhood and work-life balance: individual- and sociocultural-level factors. J Athl Train . 2015;50(8):854–861. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.5.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham JA, Dixon MA. Work-family balance among coach-fathers: a qualitative examination of enrichment, conflict, and role management strategies. J Sport Manage . 2017;31(3):288–305. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2016-0117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruening JE, Dixon MA. Situating work-family negotiations within a life course perspective: insights on the gendered experiences of NCAA Division I head coaching mothers. Sex Roles . 2008;58(1–2):10–23. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9350-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazerolle S, Eason C. A longitudinal examination of work-life balance in the collegiate setting. J Athl Train . 2016;51(3):223–232. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.4.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: facilitating work-life balance in athletic training practice settings. J Athl Train . 2018;53(8):796–811. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM. Work-life balance: a perspective from the athletic trainer employed in the NCAA Division I setting. J Issues Intercoll Athl . 2013;6:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Pitney WA, Mueller MN. Sex and employment setting differences in work-family conflict in the athletic training profession. J Athl Train . 2015;50(9):958–963. doi: 10.4085/1052-6050-50.2.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conlin M. The new debate over working moms: as more moms choose to stay home, office life is again under fire. Business Week . 2000;3699:102–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eason CM, Singe SM, Rynkiewicz K. Work-family guilt of collegiate athletic trainers: a descriptive study. Int J Athl Ther Train . 2020;25(4):190–196. doi: 10.1123/ijatt.2019-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eason CM, Rynkiewicz KM, Singe SM. Work-family guilt: the perspective of secondary school athletic trainers with children. J Athl Train . 2021;56(3):234–242. doi: 10.4085/152-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM. Navigating motherhood and the role of the head athletic trainer in the collegiate setting. J Athl Train . 2016;51(7):566–575. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.10.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Women Hakim C. careers and work-life preferences. Br J Guid Couns . 2006;34(3):279–294. doi: 10.1080/03069880600769118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eberman LE, Kahanov L. Athletic trainer perceptions of life-work balance and parenting concerns. J Athl Train . 2013;48(3):416–423. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahanov L, Loebsack AR, Masucci MA, Roberts J. Perspectives on parenthood and working of female athletic trainers in the secondary school and collegiate settings. J Athl Train . 2010;45(5):459–466. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tangney JP. Self-relevant emotions. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of Self and Identity . Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hochwarter WA, Perrewé PL, Meurs JA, Kacmar C. The interactive effects of work-induced guilt and ability to manage resources on job and life satisfaction. J Occup Health Psychol . 2007;12:125–135. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borelli JL, Nelson SK, River LM, Birken SA, Moss-Racusin C. Gender differences in work-family guilt in parents of young children. Sex Roles . 2017;76:356–368. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0579-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing Among Five Approaches 3rd ed Sage; 2013.

- 25.Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health . 2010;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health . 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description—the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol . 2009;9(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dilworth JEL. Predictors of negative spillover from family to work. J Fam Issues . 2004;25(2):241–261. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03257406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maume DJ. Gender differences in restricting work efforts because of family responsiblities. J Marriage Fam . 2006;68(4):859–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00300.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McElwain AK. An Examination of the Reliability and Validity of the Work–Family Guilt Scale. Dissertation University of Guelph; 2008.

- 31.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Fulfillment of work–life balance from the organizational perspective: a case study. J Athl Train . 2013;48(5):668–677. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.3.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakker AB, Albrecht S. Work engagement: current trends. Career Dev Int . 2018;23(1):4–11. doi: 10.1108/CDI-11-2017-0207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaufeli WB, Taris TW, Bakker AB. It takes two to tango: workaholism is working excessively and working compulsively. In: RJ Burke, Cooper CL., editors. The Long Work Hours Culture Causes Consequences and Choice . Emerald; 2008. pp. 203–226. –. [Google Scholar]