Abstract

Context

Work-life balance is a topic of interest in the athletic training profession. Particularly for parents, managing work and home roles can be challenging. Social support has been identified as a resource for improving athletic trainers' balance and quality of life and warrants further investigation.

Objective

To explore the sources and perceptions of social support among athletic trainers with children.

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

Collegiate and secondary school settings.

Patients or Other Participants

Thirty-two athletic trainers who worked in the collegiate (12) or secondary school (20) setting participated. All individuals (19 females, 13 males) were parents, and they ranged in age from 25 to 72 years, with 2 to 52 years of experience as athletic trainers.

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants were recruited from a larger cross-sectional survey. A semistructured interview was developed by the research team and reviewed by a peer expert in the field. Respondents completed the interview protocol, which contained questions in numerous areas related to work-life balance. Data analyses were guided by the research questions related to social support and used a phenomenologic approach. We researchers immersed ourselves in the data and engaged in a coding process. Researcher triangulation and peer review were used to establish credibility.

Results

Our participants found social support in their work and home lives. Support was described by source (eg, supervisors, coworkers, spouses, family, friends) and type (eg, emotional, tangible, network). Respondents perceived that support stemmed from understanding, flexibility, sharing responsibilities, and shared life experiences, which aided them in balancing their roles.

Conclusions

Athletic trainers valued social support and used different types of support to help create work-life balance. Support in the workplace, at home, and from the profession is necessary for athletic trainers who are parents, as it provides a means to help balance roles and responsibilities.

Keywords: work-life interface, collegiate setting, secondary school setting

Key Points

Social support (eg, emotional, tangible, network) was valuable in helping athletic trainers attain work-life balance.

It is important for athletic trainers in the traditional settings (ie, secondary school and college or university settings) to have support both at home and in the workplace to help manage their responsibilities as working professionals and parents.

Work-life balance reflects a positive outlook on an individual's management of his or her work, family, and life roles.1,2 The term balance must not be confused with equity of time or energy devoted to one's life roles. Rather, balance should center on fulfillment and a satisfying involvement among all roles that compete for an individual's time and energy. Balance is defined differently by everyone. As a concept, work-life balance was founded on the theory of role engagement as well as conflict. It is important to have the opportunity to participate in one's life roles, not necessarily equally but with ease and stability.3 Work-life balance can be compromised when a person lacks enough time or energy to engage in one life role due to the demands of other roles. This can be referred to as negative spillover in which the person may experience role conflict or work-life conflict.4 When balance is achieved, work-life conflict can be mitigated.

Work-life balance has become a key concern for those in sport organizations due to the demanding nature of the work environment.5 Most often, time limits the fulfillment of work-life balance for those employed by sport organizations. This is especially true for athletic trainers (ATs), as they often work weeks of 60+ hours, with many night and weekend hours.6–8 In the collegiate setting, the workweek can also include frequent travel.6,7,9 Although attainment of work-life balance is fundamentally based on an individual's personal interests and selection of life roles, workplace demands and responsibilities can have large influences.6 Therefore, strategies to help create work-life balance are often described from the organizational and individual perspectives.6

Social support or support networks have been found to positively affect work-life balance.10,11 Social support transcends the workplace and family life, as an individual can benefit from emotional concern and care as well as assistance in managing the expectations of various roles.10 The idea of social support originated from social exchange theory, which suggested that interpersonal relationships can offer reciprocation of valued resources.12,13 Social support networks in the workplace can include coworkers and supervisors, while family members, spouses, or friends can provide support from home. Athletic trainers reported that having support networks both at home and in the workplace helped to combat the demanding nature of their jobs in the more traditional sport organizational setting.6,8,14

The literature15–17 demonstrated that social support can be offered via various platforms and types. Similarly, individuals may perceive the provision of some types of support as more helpful or beneficial than others. The premise is that support helps reduce the stress associated with balancing one's life roles through expressions of care and advice, assistance in completion of tasks, and assuming responsibility in the absence of the individual. For anyone balancing multiple roles, social support is important. However, it is likely that the AT who is simultaneously engaging in parenthood may place a high value on social support. In particular, social support may offer help in caring for children or completing other household duties that can be affected when working long hours each week. Although the athletic training literature is robust regarding strategies used to help create work-life balance, few researchers have looked at the support parents value or use to create a balanced life. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to explore the sources and perceptions of social support in personal and work-based relationships among ATs with children in the collegiate and secondary school settings. The following research questions (RQs) supported the study:

RQ1: Did ATs who were parents find value in social support for creating work-life balance?

RQ2: What types of social support did ATs use, and how did they perceive this support as beneficial when trying to create work-life balance?

METHODS

Research Design

Descriptive phenomenology is a popular method when the primary purpose of the study is to explore and describe the experiences of a specific group of individuals to better understand a phenomenon.18,19 We selected this approach as we sought to describe the experiences of ATs who were parents working in more traditional settings. The descriptive element of the framework allows for a narrative to be shared by the participants themselves, which adds realness and rigor to the findings.19 The qualitative aspect of this paper was part of a larger mixed-methods study.20–22

Participants

We used a purposive sampling process to fully describe the experiences of collegiate and secondary school ATs who were parents. We used the following criteria to actively recruit our participants: (1) employment in the collegiate or secondary school setting, (2) a full-time position that included at least 50% patient care duties, and (3) having at least 1 child. We replaced the name of each participant with a pseudonym for privacy and confidentiality reasons.

In total, 32 ATs (19 females, 13 males) met our inclusion criteria and participated in the study. Of those 32, 12 collegiate and 20 secondary school ATs shared their experiences. Our respondents ranged in age from 25 to 72 years of age and had 2 to 52 years of experience as ATs. Additional demographics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Pseudonym |

Sex |

Age, y |

Experience as an Athletic Trainer, y |

Average Hours Worked per wk |

Married? |

Years Married |

Spouse Employed Full Time? |

No. of Children |

Setting |

| Aly | F | 35 | 13 | 45 | Yes | 4.5 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Anna | F | 44 | 19 | 47.5 | Yes | 8 | Yes | 2 | College or university |

| Beth | F | 43 | 20 | 40 | Yes | 12.5 | Yes | 1 | College or university |

| Brittany | F | 32 | 10 | 35 | Yes | 5.5 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Casey | F | 50 | 26 | 25 | Yes | 22 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Cassie | F | 34 | 12 | 50 | Yes | 0.5 | Yes | 2 | College or university |

| Derek | M | 31 | 7 | 11 | Yes | 4 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Fran | F | 31 | 8 | 40 | Yes | 8 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Ethan | M | 47 | 25 | 66 | Yes | 24 | Yes | 2 | College or university |

| Evan | M | 35 | 10 | 47.5 | Yes | 10 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Gabby | F | 25 | 2 | 30 | No | N/A | N/A | 1 | Secondary school |

| Garett | M | 49 | 25 | 50 | Yes | 19 | Yes | 2 | College or university |

| Hank | M | 51 | 29 | 47.5 | Yes | 23 | Yes | 1 | College or university |

| Henry | M | 33 | 9 | 40 | Yes | 10 | No | 3 | Secondary school |

| Ian | M | 48 | 22 | 36 | Yes | 15 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Jake | M | 39 | 19 | 55 | Yes | 13 | No | 4 | College or university |

| Jen | F | 33 | 9 | 60 | Yes | 3 | Yes | 1 | Secondary school |

| Kayla | F | 31 | 10 | 45 | Yes | 8 | Yes | 1 | Secondary school |

| Kelly | F | 32 | 8 | 45 | Yes | 5 | Yes | 1 | College or university |

| Luke | M | 72 | 52 | 11 | Yes | 49 | No | 2 | Secondary school |

| Matt | M | 33 | 12 | 55 | Yes | 5 | Yes | 1 | College or university |

| Megan | F | NA | 20 | 60 | Yes | 19 | Yes | 3 | Secondary school |

| Natalie | F | 31 | 10 | 45 | Yes | 3 | Yes | 1 | Secondary school |

| Nicole | F | 33 | 12 | 45 | Yes | 6 | Yes | 2 | College or university |

| Olivia | F | 30 | 8 | 40 | Yes | 5 | Yes | 1 | Secondary school |

| Pat | M | 38 | 15 | 57.5 | Yes | 12 | Yes | 2 | Secondary school |

| Paula | F | 37 | 15 | 45 | Yes | 13 | Yes | 3 | College or university |

| Rachel | F | 33 | 11 | 60 | Yes | 1 | Yes | 3 | Secondary school |

| Sarah | F | 36 | 13 | 45 | Yes | 9 | Yes | 1 | Secondary school |

| Tara | F | 30 | 7 | 33 | No | NA | NA | 1 | Secondary school |

| Walter | M | 51 | 26 | 80 | No | NA | NA | 2 | Secondary school |

| Zach | M | 30 | 8 | 70 | Yes | 9 | Yes | 2 | College or university |

Abbreviations: AT, athletic trainer; F, female; M, male; NA, not applicable (If the respondent answered single to the question about marital status, then NA was used for the questions on years married and spousal employment).

Data-Collection Procedures

Recruitment

We recruited our participants from a larger cross-sectional survey21 that examined work-family conflict among collegiate and secondary school ATs who were parents. At the end of the survey, individuals provided their email addresses to indicate their interest in sharing and willingness to discuss their experiences in one-on-one interviews. Email addresses were collected separately and not linked to survey responses. Using data saturation as our guide, we recruited participants from each employment setting until saturation was achieved. We obtained institutional review board approval before recruitment began.

Instrumentation

Based on the current literature,7,9,23 we developed an interview protocol that reflected the purposes of our study. Our interview guide was comprehensive, focusing on multiple areas related to work-life balance (eg, work-family conflict, work-family guilt, support). The same interview protocol was used to conduct previous research as part of one large study.20,22 However, different data were analyzed to answer our research questions specific to the focus area of this study, which was support. The questions from the interview guide related to support are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interview Guide Questions Pertaining to Supporta

| ▪ Who is your biggest source of support in helping to balance your work and family responsibilities? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instrument is reproduced in its original format.

The interview followed a semistructured format as is commonly used in phenomenologic research.18 This allows for a more naturalistic dialogue between the participant and interviewer, which can offer more in-depth information from the former. Before data collection, we asked a peer expert to review the content of the instrument and provide us with feedback to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the questions. Our peer was knowledgeable about work-family conflict and had publication success in both qualitative research and the topic of work-life balance.

Procedures

All participants completed the semistructured interview protocol with the lead author (K.M.R.). Having 1 author complete all the interviews was purposeful in order to preserve the semistructured nature and allow for a more natural conversation. The lead author took field notes throughout the interview, which promoted consistency among the interviews and enabled the determination of saturation. All participants consented orally before the interview session. Interview sessions lasted approximately 40 minutes, and all were transcribed verbatim before the analyses were conducted.

Data Analysis and Credibility

The first and second authors (K.M.R. and S.M.S.) used the principles of a phenomenologic framework to evaluate the data. Patton24 suggested that qualitative researchers must undergo training and be equipped to manage the data from a holistic lens inductively. Both authors had been formally trained in the analyses and had experience coding qualitative data inductively. Data immersion was the first step of the coding process, whereby each transcript was read thoroughly to best understand the experiences of our participants. To accurately describe the perceptions and experiences of our participants, immersion into the data was key. Immersion before full analyses allows the researcher to appreciate the more dominant and important findings. Once immersion occurred, we read the transcripts to label key pieces of information that spoke to support networks for ATs who were parents. These key pieces of information were grouped and categorized with an appropriate label to reflect their meaning. When coding was complete and the first and second author agreed, the findings were shared with a peer for confirmation of the analyses. Multiple-analyst triangulation and peer review were done to establish credibility of the findings, as described previously. These 2 strategies, along with data saturation and the credibility of the researchers, provided rigor for the findings of the study.

RESULTS

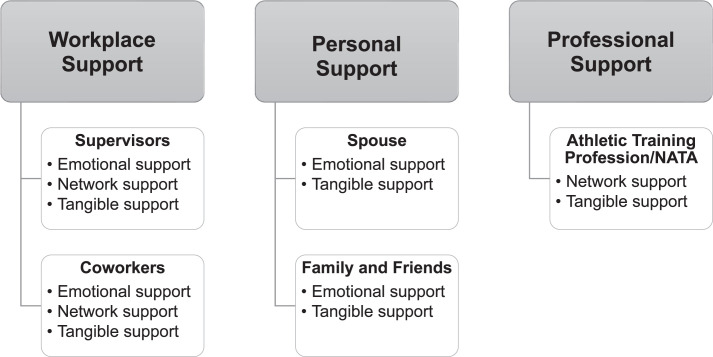

Data analyses revealed that our participants found social support in their workplaces and home lives (Figure). Within these 2 major themes, each was described in terms of a source of support (ie, the person providing the support) and the type of support (ie, how support was received or used). Perceptions of support stemmed from an understanding of one's roles and responsibilities by others, flexibility in the workplace, the sharing of responsibilities both at home and at work, and similar life experiences as others who either presently or in the past had comparable work and home demands. From a more global perspective, our respondents also recognized that the profession of athletic training supplied support.

Figure.

Sources and types of support: Participants perceived support in the workplace, in their personal lives, and from the profession. For each of these areas, participants described a source of support (eg, coworkers, family, friends) and the type of support (eg, emotional, network, tangible) that was provided by those individuals or entities.

Abbreviation: NATA, National Athletic Trainers' Association.

Workplace Support

Our participants identified supervisors and coworkers as individuals who supported their efforts to balance their professional and personal lives, which included being parents. Discussions were centered on feelings of recognition by their supervisors and coworkers regarding the high demands of the family role. Our participants noted that the support was manifested through both caring (ie, emotional and network support) and providing time to attend to the family role (ie, tangible support).

Supervisors

Supervisors, including head ATs, athletic administrators, or both, were acknowledged as individuals who supported our participants. Nicole said, “My employers understand that being a mother is a high priority for me. They knew that when they offered me the job.” Participants frequently mentioned understanding from their supervisor, most often a head AT or athletic administrator, as a source of support in balancing their roles as parents and ATs. In her interview, Beth shared, “Our administration has been accommodating with understanding my needs and understanding what I need in order to continue working here as an athletic trainer.” Ethan, too, felt his institution played a role: “To tell you the truth, I'm lucky, knock on wood. My institution is understanding.” Paula stated:

I think it's helpful to have a boss who understands that you have to care for your family and do your job. There are also some components where family is more important, but we can figure out ways to adapt and adjust as needed; in that way, we can do both things.

In a contrasting experience, Zach stressed the importance of a supervisor sharing similar life experiences to provide support. In his current job, Zach did not feel his employer understood his role as a parent: “I think that's difficult to say because I think I would say no. Nobody really understands what it's like. I don't think my supervisor—[she] is our medical director—[understands]. She's married but doesn't have any children, so I think that changes things, too.”

The type of support offered by our participants' supervisors was described as a sense of belonging and common life experiences, support that was viewed as both emotional and networking. Emotional support can be demonstrated by caring through actions of sympathy or empathy, which can be stimulated by shared or past experiences. Network support is simply a social connection and relationship based on shared experiences. In this case, being an AT and a parent served as the platform for belonging. Ethan addressed his personal experiences:

I would say even my athletic director has been extremely understanding. He has 3 grown children, but he understands. I think he can read me when I get very stressed, and he doesn't push the envelope, which is great.

Hank commented:

The head [athletic] trainer himself has 2 kids, and he'll bring his kids to work and understands that. Our staff is kind of big, not huge, but to where we can kind of say, “Hey, can somebody do this while I go pick up my kid from daycare?” or “Can you do this because this came up?” So the employer is huge here.

Beth said that she has a “good set-up” at her current workplace. She observed,

I've been able to implore upon our administration that, if you overwork these people, they leave after a year. If you give them the support that they need in order to be able to have a little bit of time with [their] friends, to pass the social time with people, they're going to be much happier.

Casey had similar sentiments regarding support and performance in the workplace:

I think when your employer understands that you're a person. . . and that by letting you do the things you need to as a parent, that's going to make you better equipped to handle your day-to-day duties as their employee.

Coworkers

Our participants perceived support received in the workplace from feelings of camaraderie due to shared life experiences related to the family role as well as finding value in family time. They believed they did not need to sacrifice their time for family or parenting due to the support, most often characterized as emotional, network, and tangible support. Tangible support involves the provision of a direct form of assistance (eg, sharing responsibilities, covering shifts, giving time off). Aly expressed that her workplace was “very family supportive” and was “part of the reason why [she] took the job.” When asked about a source of support in balancing her responsibilities, Beth said, “I would definitely say our staff. They are very understanding and accommodating when you need to step away, so that's great.” Beth's support was tangible (ie, provided assistance).

Gabby noted that her coworkers supplied tangible support by sharing job duties to allow coworkers to attend to personal life role obligations:

I am very fortunate; our staff is very helpful. We all work together, and we help each other out. So, even if it's someone who doesn't have children, and they haven't been home in 5 days to do laundry, I'll step up and cover for them, so they can go home and do their life in general, and vice versa.

Ethan received support from his coworkers:

My staff at work, they understand. They know I'm splitting my time between home, and if I want them to cover for me, they know that I'm not going to take it just because of the heck of it. In fact, they know that's important to me, and that's what I'm going to do, and they have no problems with that. They know I put in the work all the other times and that I'm always there.

Ethan's experiences reflected emotional support, as they demonstrated understanding regarding the time parenting required. Ethan felt as though he could take time for his family role without sacrifice by indicating, “They just don't question. Do what you got to do. They don't question what my motives are, what my role is, or what my plans are. They accept it, and they're supportive of it.”

Evan explained:

I lean on some of our coaches, too. You know, our [athletic director is] basically there when we're there. He's got older kids, so I'm able to lean on him a little bit, too, and get advice on how to handle it. Usually, his response is: “You go be with your family, and we will figure it out,” which all makes it easier.

Ethan has not only network support though shared experiences but also emotional support via a sympathetic mindset regarding family role needs.

Aly described her coworker as another source of support:

My coworker in general [is a source of support], because he's awesome. Like I said, at the end of the month, we just sit there and divide it up, and it's just whatever reason you want the day off, it doesn't matter. Not the day off, but like the early night, you know, because his wife kind of works right with our students. So, whenever she's got an early night, like he needs an early night with her, it just makes sense. Just because they don't have kids doesn't mean that I have the only vote in the situation, and so we just divide it up as equitable as it can be.

Brittany said:

Times when my son was sick and we just had a couple practices, it was like, “Go home. Leave early. We got it. We'll call so and so. They're down the road. We'll enact our emergency action plan. Go take care of your son. Don't worry about us. We're taken care of,” or if I can't come in and they're looking for something, it's like, “It's fine. Where is it? I'll grab it. You're fine.”

Ian acknowledged support from other ATs as well:

So other athletic trainers, for sure, so not only sending me pictures of my own kids and whatnot, but there are times where I can't travel [to] a certain away game, but I know that they're there, and I trust them to take care of my athletes.

Personal Support

Personal social support was offered by individuals in our participants' home lives, including spouses, family members, and friends. These individuals were identified as people who provided our participants with understanding and support as they navigated parenthood and athletic training. The support was depicted as emotional and tangible.

Spousal Support

Spousal support was often tangible (assisting by caring for children) and emotional (showing concern, sympathy). Many of our respondents were quick to identify their spouses as important supports and reasons for balancing their careers and parenthood. Aly said, “Having a very supportive spouse is key to balancing it.” Fran agreed: “Truly my husband [is her biggest supporter]. I mean, he's been in the trenches with me doing this for the last almost 9 years now.” Evan said, “My wife helps me [by providing support]. That's kind of where I go and where I turn to, you know, to kind of help prioritize and get feedback and communicate.”

Emotional support was characterized as kindness, understanding, and acceptance of the demanding nature of the profession of athletic training. Zach's reflections on his wife highlighted the need for understanding:

My wife, she's an angel. I think that's the most important thing. If anybody asks me how you do it, you've got to find yourself a woman who's just an absolute rock star. There's no other way to do it. She's incredibly supportive. She's amazing. That's the only reason that we're able to make this work is because she is so supportive and is behind it.

Garett talked about how his wife's acceptance of his job and her understanding allow him to balance it all:

I'm fortunate that my wife understands my job. She understands that I love what I do and the importance of what we do and does not give me grief for having to travel on a weekend or multiple weekends or spring trips with baseball or lacrosse or softball or things like that. I'm not getting grief every time I come home late, and she has an understanding of that job.

Tangible support came in the form of taking over household duties or other domestic and parenting tasks. Megan commented:

So my husband just keeps the balance, not only like with work and family and whatever, but he just kind of. . . he helps keep things scheduled and organized, and then, you know, we can work through the schedule, so that it's not all on me or all on him.

Rachel remarked on her husband's help at home: “When I'm busiest, he starts taking over things around the house.” Pat talked about his wife helping at home, too:

She's like my biggest advocate. I just finished my doctorate in athletic training a couple years ago. So she ran the house and kept the kids together while I got my degree. Things like that I'd never be able to do without her support.

Pat went on to say, “She just lets me be what I have to be.”

Friends and Family

Our participants shared that many friends and family provided support, mostly in the form of childcare, a tangible type of support. Many individuals relied on their in-laws or parents for childcare, which allowed them to balance working and their families. Natalie expressed:

My family is local and also my in-laws. So we're actually really blessed. They are our main childcare, and then when they're not available, we find other means, but yeah, I have a very large support system, and that's amazing.

Fran said her “mom is always willing to come and stay with the boys if I need something.” Cassie's mother-in-law helped as well: “I would say my mother-in-law is probably the biggest supporter because she provides childcare for us.”

Friends were identified as supportive in supplying both childcare and emotional support. Nicole called on her best friend as her sounding board and someone who could step in when she needed physical help:

My best friend is my emotional support. She's the one I call when I'm upset because I'm so tired and my laundry room looks like a disaster. She's also a huge source of support for when we need help. She lives a few states away. She's also our son's godmother, but when I need somebody to come stay because I'm with lacrosse and my husband is on the road, she's the first one that will stay for 4 days and give our son the exact level of care that we've been giving him.

The concept of “it takes a village” and the need for a support system larger than just a spouse was shared by several participants. Rachel eloquently illustrated this concept:

I have what we call a village, a village family. So actually, my best friend, and then there are friends everywhere, they're more than happy to help out. They're actually going to be watching my child for the first 6 months of her life, and willingly. . . We all look after each other. So like, right now, the summer is my time, and I usually pick up and do other things like that, but just having that support system is what makes it easier because, if something happens, you can call them.

Professional Support

Professional support was described by our participants on a larger scale in a more indirect manner, simply drawing on the support of other ATs from the larger community and with whom they were not in direct daily contact in the workplace. The need for this type of social support was based on a sense of belonging (ie, networks) through shared experiences of being both a parent and an AT. The concept of support groups was recognized by many respondents, including some women who were part of a Facebook group. Anna stated, “That's actually a really good site. It's a really good site.” Our participants identified this group as sharing similar experiences, which enabled them to realize they were not alone. Sarah told us:

I would say my biggest support, there's an online Facebook group, Athletic Trainer Moms. That mom group has literally got me off the ledge. It's such a supportive network. The ladies in there, like a lot of them I haven't even met before, but we support each other if there's questions or if you're just having a bad day or if you have mom questions, baby questions. Just. . . it's great to have people that understand your role and what you're doing and that you're balancing motherhood on top of it.

Derek mentioned having “support groups for athletic trainers that have kids” would be “pretty cool and really good thing for them.” Henry noted:

Yeah, there could always be a committee, a group, a support group that really looked at how to do athletic training successfully; like we're supposed to uphold those standards as well as having a family.

Luke cited resources from the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) that were already in place: “You know, I think they can have resources for you. ATs Care is a great program; it is a place for us and for the profession.” These support groups were viewed as creating a sense of belonging, involving others with similar experiences who could offer empathy.

Professional Support From the NATA

Many of our respondents indicated that, beyond the workplace and home support, the profession of athletic training needed to provide support to aid in work-life balance. Garrett and Cassie both discussed wanting the profession to step up and provide tangible support to its members. Garrett explained, “Let's worry about our members. Let's try to help them out. Let's try to do stuff for them. That support from the organization itself, that goes a long way.” Cassie felt, “It would be nice if the profession could kind of support parents. In general, I feel like the field could do a better job at having more positions, more people employed.”

Tangible support was also a factor in staff sizes for athletic training departments. Participants believed that, with adequate staff sizes, ATs, especially those who were parents, could achieve better balance. With regard to staff sizes and work-life balance, Anna remarked:

I feel that they [the NATA] need to focus on setting and requiring a certain number of athletic trainers per sport and student-athletes because, if I had more staff, we would all have a balanced schedule.

Paula cited staff sizes as well in addition to having children while working in the profession:

I think a lot of it is just kind of normalizing having children instead of just assuming that, when you have kids, you need to get out of athletic training or pick one over the other. For a lot of things, we just need to have a big enough staff so that people can do those things. . . The schools that only have 2 athletic trainers for 16 sports, that's ridiculous. There's no way they're going be able to balance themselves.

DISCUSSION

Social support is intended to be helpful in managing one's responsibilities. It is a function of relationships in a person's work life, home life, or both. Accumulating information suggests that social support is a key element in the work-life relationship, particularly when it has positive implications for finding balance.25 In our study, we aimed to identify if ATs who were parents found value in social support to help create work-life balance and which types of support they used.

Value of Social Support

Collegiate and secondary school ATs who were parents valued the social support they received both in the workplace and at home. Support in these environments came from different individuals. In the workplace, ATs received support from their coworkers and supervisors. At home, they were supported by their spouses, friends, and family. Respondents also identified support from the profession. Researchers6 have characterized these individuals and many others as potential sources of support for ATs.

In the workplace, our participants appreciated the understanding and flexibility that came from their coworkers and supervisors in terms of their parental roles and responsibilities. Not only was workplace support (ie, when employees perceive their wellbeing is important to their employer25) valuable to the employee, it was also valuable to the employer. Investigators in the collegiate setting found that social support increased retention in the field among both female26 and male27 ATs. Forsyth and Polzer-Debruyne28 demonstrated that, when employees perceived work-life balance support from their employers, job satisfaction increased, and work pressures decreased. Support that promotes availability for participation in home, life, and family roles can enhance one's wellbeing. It makes the workplace or organization more desirable, which can increase employee commitment.29,30

At home, understanding and help with household tasks and childcare from spouses, family, and friends were also of value. For those who are married or in a relationship, a work-supportive partner is helpful; support from one's spouse is a vital component of a successful relationship.16 This can alleviate stress when an individual must take part in an important work event instead of a family event, knowing his or her partner will not react negatively to the decision.29 Recent literature20,22,31 has shown that ATs experienced feelings of guilt due to all of their responsibilities and demands. Guilt can arise as a negative emotional response when individuals have conflicting responsibilities (eg, choosing between work and family). Parents may experience guilt when managing their roles and trying to be present as both professionals and parents.32 For our participants, support helped to mitigate negative feelings and relieved perceived pressure.

Support groups specific to the profession offered a community in which participants were able to share similar experiences with others who could relate. Respondents also described ways in which the profession could provide support to its members. The NATA has recognized the importance of initiatives that focus on work-life balance and recently released a position statement6 on the topic. As suggested by our participants, the profession can supply support in multiple ways, such as creating support groups and stressing the need for appropriate and adequate staff sizes to employers. Additionally, because the NATA has a variety of documents and materials available, bringing more attention to these resources may be beneficial.

Types of Social Support

To manage stress and find work-life balance, ATs have described support and teamwork as useful coping mechanisms.14,33 They also noted external support systems were helpful ways to manage their various roles.23,33,34 Developing a strong support network can improve quality of life by providing people to rely on.6,35,36 At the individual level, supporters can offer encouragement, comfort, assistance, friendship, and consolation in times of need.10 It was clear that ATs valued the emotional, tangible, and network support they received from these sources.

Emotional support can be expressed through love, empathy, concern, and care.16 Our participants received emotional support from many individuals who supplied a listening ear, understood without judging, and expressed sympathy. Respondents received this support for both their home and work responsibilities and from multiple sources, depending on the support needed. For example, in some cases, ATs discussed work stress with their coworkers, and in others, they vented to friends or family when upset. Tangible support involves the provision of goods, services, or other resources.16 Our participants often discussed childcare as a form of support and assistance given by those in their personal lives. Additionally, ATs cited help with household tasks and chores. In the workplace, adjusting schedules with coworkers and being able to leave early or come to work late served as tangible support. Network support helps to create a sense of belonging and connectedness.16 Our respondents experienced this through their workplace support networks with their supervisors and coworkers as well as with AT colleagues and friends through support groups.

As with any field, the profession of athletic training has unique aspects, especially in the traditional settings (ie, secondary school and collegiate or university settings). These include but are not limited to a 24/7 mentality, long working hours, weekend hours, and travel requirements.6–8 These challenge the AT who is a parent seeking to balance the responsibilities of each role. Support via the different methods expressed by our participants can help mitigate these challenges and provide ATs with a means of achieving better work-life balance. Nonetheless, regardless of distinctive job demands of the athletic training field, being a parent carries inherent responsibilities. However, these responsibilities are not isolated to ATs who are parents. Rather, these responsibilities, in addition to job workloads, are universal despite a parent's job setting and career path and can lead to feelings of work-family conflict and guilt.32

Limitations and Future Research

Our findings reflect the experiences and perceptions of a small group of ATs in traditional employment settings who were parents. Support may be perceived differently by those who are not parents or are employed in other settings. Future researchers should examine the support networks of those who are not married and those who do not have children. Also, exploring support networks, especially from the perspective of the employment setting, could offer distinctive insights, as the expectations and job duties of an AT outside the traditional setting might be different. Given that the need for support is individualized, additional factors that may affect perceived support, including demographic and employment characteristics such as race and salary, are important to evaluate as well. Further, it may be worth investigating specific areas in which ATs believe the NATA could provide more support. Measurements of social support exist; thus, the authors of future studies can evaluate the construct quantitatively. Our results are from the individual ATs' perspectives only and not from the employer perspective. Future investigators should address employers' views on the support they provide and its effect on work-life balance.

CONCLUSIONS

Support can originate from many sources and arrive in different forms. Athletic trainers who were parents valued and heavily relied on their support networks to help with parental and job duties. The type of support needed varies for each individual but includes support both in the workplace and at home. Support needs can change over time, depending on an individual's personal and professional responsibilities, personal and family characteristics, and life stage, among other factors. However, it is important that ATs have the support they need to attain balance, manage their responsibilities, and be successful in both roles. The profession of athletic training can assist by creating more resources and better support for ATs with children, which in turn may decrease turnover and increase retention in the field.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clark SC. Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance. Hum Relat . 2000;53(6):747–770. doi: 10.1177/0018726700536001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsons D. Work-Life Balance: A Case of Social Responsibility or Competitive Advantage? Human Resources Department Georgia Institute of Technology; 2002.

- 3.Yadav T, Rani S. Work life balance: challenges and opportunities. Int J Appl Res . 2015;1(11):680–684. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser F, Williams L. Work-life balance, rhetoric versus reality? An independent report commissioned by UNISON. The Work Foundation; 2006 Accessed August 3 2021. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.501.7235&rep=rep1&type=pdf .

- 5.Graham JA, Smith JA, Dixon MA. Choosing between work and family: analyzing the influences of work, family, and personal life among college coaches. J Issues Intercoll Athl . 2019;12:427–453. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: facilitating work-life balance in athletic training practice settings. J Athl Train . 2018;53(8):796–811. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train . 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train . 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitney WA. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train . 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson DS, Perrewe PL. The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: an examination of work-family conflict. J Manage . 1999;25(4):513–540. doi: 10.1177/014920639902500403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcinkus WC, Whelan-Barry KS, Gordon JR. The relationship of social support to the work-family balance and work outcomes of midlife women. Women Manage Rev . 2007;22(2):86–111. doi: 10.1108/09649420710732060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med . 1976;38(5):300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladebo OJ. Effects of work-related attitudes on the intention to leave the profession: an examination of school teachers in Nigeria. Educ Manage Adm Leadersh . 2005;33(3):355–369. doi: 10.1177/1741143205054014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Fulfillment of work-life balance from the organizational perspective: a case study. J Athl Train . 2013;48(5):668–677. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.3.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Yragui NL, Bodner TE, Hanson GC. Development and validation of a multidimensional scale of family-supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) J Manage . 2009;35(4):837–856. doi: 10.1177/0149206308328510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Burleson BR. Effects of sex, culture, and support type on perceptions of spousal social support: an assessment of the support gap hypothesis in early marriage. Hum Commun Res . 2001;27(4):535–566. doi: 10.1093/hcr/27.4.535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wills TA, Shinar O. Measuring perceived and received social support. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social Support Measurement and Intervention A Guide for Health and Social Scientists . Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed Sage; 2013.

- 19.Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health . 2010;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eason CM, Rynkiewicz KM, Mazerolle Singe S. Work-family guilt: the perspective of secondary school athletic trainers with children. J Athl Train . 2021;56(3):234–242. doi: 10.4085/152-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singe SM, Rynkiewicz KM, Eason CM. Work-family conflict of collegiate and secondary school athletic trainers who are parents. J Athl Train . 2020;55(11):1153–1159. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-381-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singe SM, Rynkiewicz KM, Eason CM. A parental perspective work-life balance and guilt in collegiate athletic trainers: a descriptive qualitative design. J Athl Train Accepted manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mazerolle SM, Ferraro EM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Factors and strategies contributing to the work-life balance of female athletic trainers employed in the NCAA Division I setting. Athl Train Sports Health Care . 2013;5(5):211–222. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20130906-02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res . 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kossek EE, Pichler S, Bodner T, Hammer LB. Workplace social support and work-family conflict: a meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work-family specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers Psychol . 2011;64(2):289–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train . 2010;45(3):287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A. Factors influencing the decisions of male athletic trainers to leave the NCAA Division-I practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Train . 2013;18(6):7–12. doi: 10.1123/ijatt.18.6.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forsyth S, Polzer-Debruyne A. The organisational pay-offs for perceived work–life balance support. Asia Pac J Hum Resour . 2007;45(1):113–123. doi: 10.1177/1038411107073610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenhaus JH, Powell GN. When work and family collide: deciding between competing role demands. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process . 2003;90(2):291–303. doi: 10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00519-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen TD. Family-supportive work environments: the role of organizational perceptions. J Vocat Behav . 2001;58(3):414–435. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eason CM, Singe SM, Rynkiewicz K. Work-family guilt of collegiate athletic trainers: a descriptive study. Int J Athl Ther Train . 2020;25(4):190–196. doi: 10.1123/ijatt.2019-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goncalves G, Sousa C, Santos J, Silva T, Korabik K. Portuguese mothers and fathers share similar levels of work-family guilt according to a newly validated measure. Sex Roles . 2018;78(3–4):194–207. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0782-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazerolle S, Eason C. A longitudinal examination of work-life balance in the collegiate setting. J Athl Train . 2016;51(3):223–232. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.4.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Trisdale WA. Work-life balance perspectives of male NCAA Division I athletic trainers: strategies and antecedents. Athl Train Sports Health Care . 2015;7(2):50–62. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20150216-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cutrona CE. Social support and stress in the transition to parenthood. J Abnorm Psychol . 1984;93(4):378–390. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.93.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones WH, Perlman D, editors. Advances in Personal Relationships . JAI Press; 1987. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]