Abstract

Introduction:

Polysubstance use—the use of substances at the same time or close in time—is a common practice among people who use drugs. The recent rise in mortality and overdose associated with polysubstance use makes understanding current motivations underlying this pattern critical. The objective of this review was to synthesize current knowledge of the reasons for combining substances in a single defined episode of drug use.

Methods:

We conducted a rapid review of the literature to identify empirical studies describing patterns and/or motivations for polysubstance use. Included studies were published between 2010 and 2021 and identified using MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and Google Scholar.

Results:

We included 13 qualitative or mixed-method studies in our analysis. Substances were combined sequentially to alleviate withdrawal symptoms or prolong a state of euphoria (“high”). Simultaneous use was motivated by an intention to counteract or balance the effect(s) of a substance with those of another, enhance a high or reduce overall use, and to mimic the effect of another unavailable or more expensive substance. Self-medication for a pre-existing condition was also the intention behind sequential or simultaneous use.

Conclusion:

Polysubstance use is often motivated by a desire to improve the experience based on expected effects of combinations. A better understanding of the reasons underlying substance combination are needed to mitigate the impact of the current overdose crisis.

Keywords: polysubstance use, polydrug use, misuse, drug combination, co-use, co-ingestion, rapid review

Highlights

The use of multiple substances in a single episode is common, but increases the risk of an acute toxicity event.

Polysubstance use is driven by people’s experience and expectation of substance effects.

Substances can be combined sequentially to alleviate withdrawal symptoms or prolong a state of euphoria (“high”).

Substances can be used simultaneously to counteract or balance their effect(s), enhance a high, reduce overall use, or mimic the effect of another substance.

While substances are generally combined to improve the experience, reducing overall use or self-medicating a pre-existing condition are also motivations.

Introduction

Polysubstance use, the consumption of more than one substance close in time, with overlapping effects,1,2 is increasingly recognized as an urgent public health issue.3-6 The co-involvement of stimulants, benzodiazepines and alcohol increases the risk of acute opioid toxicity7 and has been identified as one of the key drivers in the rise in opioid-related mortality in North America.3-6 In Canada, 22828 apparent opioid toxicity deaths were recorded between January 2016 and March 2021.8 Although it is most prevalent among people with problematic use,6,9-11 polysubstance use is far-reaching and occurs across populations and age groups.12-16

Overdose death rates have risen rapidly since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.8 Between April and September 2020, in the 6 months after the implementation of COVID-19 prevention measures, there were 3351 apparent opioid toxicity deaths in Canada, representing a 74% increase over the previous 6 months (1923 deaths between October 2019 and March 2020).8 Recent evidence suggests that physical distancing measures have contributed to this situation by reducing the availability of treatment and harm reduction services for people who use substances.17 Although the literature on polysubstance use in the context of COVID-19 is still nascent, findings from recent reports also suggest that self-medication and the effects of abstinence from no longer accessible drugs has resulted in an increase in the number of substances used simultaneously.18 This trend is a concern given that it contributes to multiple dependencies,19-21 especially when substances are consumed to mitigate a negative symptom, for example, to manage pain.22

Studies have shown that people combine substances with the intention of minimizing harm, reducing negative symptoms, increasing pleasurable sensations and enhancing overall experience, despite the risk of acute toxicity inherent to polysubstance use.23 Qualitative and mixed-method studies have reported various motivators of polysubstance use in specific populations,24-28 but a comprehensive synthesis of the literature is missing. As studies relying on qualitative data tend to be small, a synthesis of the literature could provide a broader and more complete picture of polysubstance use motivations in the population, help identify common and less common motivating factors, and inform substance-use intervention and prevention programs and policies.

In this review of qualitative evidence, we aim to summarize the current state of knowledge on the way people choose to combine substances in a single episode, either at the same time or sequentially, to achieve desired effects.

Methods

Search strategy

We developed this review using the methods described in the Rapid Review Guidebook.24

An electronic database search strategy was developed with a librarian based on a pre-specified protocol (available from the authors on request). We searched MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO databases for peer-reviewed studies published between January 2010 and March 2021. We identified grey literature by searching the Google and Google Scholar databases for governmental reports and webpages of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation (OECD) and of OECD member countries. An ancestry search of all the references cited by all included peer-reviewed articles and a manual search in Google Scholar for key concepts such as pattern of polysubstance use were carried out to capture relevant studies that may not have been indexed in the searched databases.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) reported on the pattern or motivation of polysubstance use; (2) were qualitative or mixed methods using original data; (3) were conducted in OECD countries; and (4) were written in French or in English. There were no restrictions on study population or context/setting.

Studies were excluded if they (1) reported motivations only for alcohol and/or cannabis and/or tobacco or a combination of these with a non-psychoactive substance because the focus was on combinations associated with more severe problematic use;25 (2) reported no specific combination(s); (3) relied on data collected before 2005, to capture recent patterns of use; (4) described the probability of combining substances with no mention of motivations; or (5) did not specify a time period of use or described the use as taking place for a period longer than 24 hours.

Study selection and data collection

Two reviewers (MBF, CL) independently screened titles and abstracts and retrieved potentially relevant studies for full-text review. Three reviewers (MBF, GC, GG) independently extracted data from the included studies. Any discrepancies between reviewers at screening and full-text review were resolved via consensus. For all included publications, the study country, objective(s), population, sample size, data collection method, years of data collection, basic demographic data of study participants including age, sex, substances under study and combinations of substances and or classes were extracted. Motivations for combining different substances, and patterns of substance use (simultaneous or sequential), were coded.

Quality appraisal

Three reviewers (MBF, GC, GG) independently assessed the quality of included studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).26,27 This tool has been developed and validated to critically appraise the methodological quality of different study designs. The MMAT uses five questions to assess the appropriateness of the study design for the research question, the potential bias and the quality of measurements and analyses, according to design.

Based on “yes,” “no” or “can’t tell” answers, a five-point quality score was created, assigning one point for each “yes” response. Studies were considered good quality (≥4 “yes” answers); moderate quality (3 “yes” answers); or poor quality (≤2 “yes” answers). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved if any of their answers to the five questions described in the MMAT tool differed. Consensus was reached through discussion between two reviewers, followed by discussions with a third if the disagreement persisted.

No studies were excluded based on their quality. (Details of the complete quality appraisal results of all included studies are available from the authors on request).

Data analysis

We extracted qualitative data on polysubstance use, including the specific substances combined and their class (stimulants, depressant, dissociative, psychedelics, etc.). We defined polysubstance use as the consumption of at least two substances at the same time (simultaneous pattern) or taken one after another within a 24-hour period (sequential pattern).

We carried out a thematic content analysis to identify the motivations and patterns of use. We coded qualitative information using a predetermined list of motivations extracted from a published review,10 allowing for more to emerge. Once the list of motivations stabilized, two reviewers (either MBF and CL, or MBF and GC) coded the verbatims separately and then compared their results. A single quote could be coded under more than one motivation. If the reviewers disagreed as to the motivation to ascribe, they resolved the disagreement through discussion, with a third reviewer joining the discussion if the disagreement persisted.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

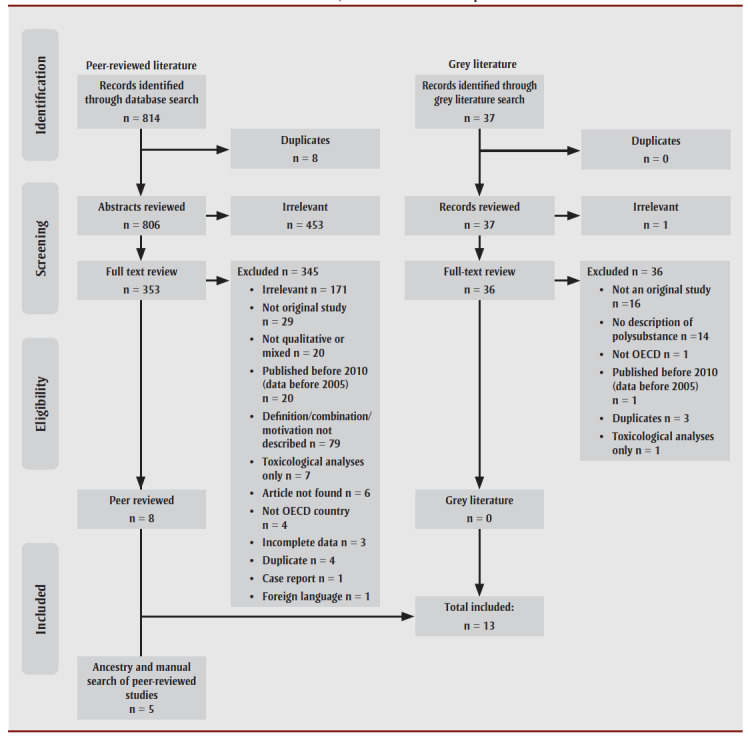

The initial electronic database search yielded 814 studies, and the grey literature search 37 records. After the removal of duplicates (n=8) and ineligible records on the basis of their title and abstract (n=453), 353 manuscripts underwent full-text review. Of these, 8 studies28-35 were included in the review (Figure1). Five more peer-reviewed studies were added through the ancestry and manual searches.14,36-39

Figure 1. Data identification, selection and extraction process.

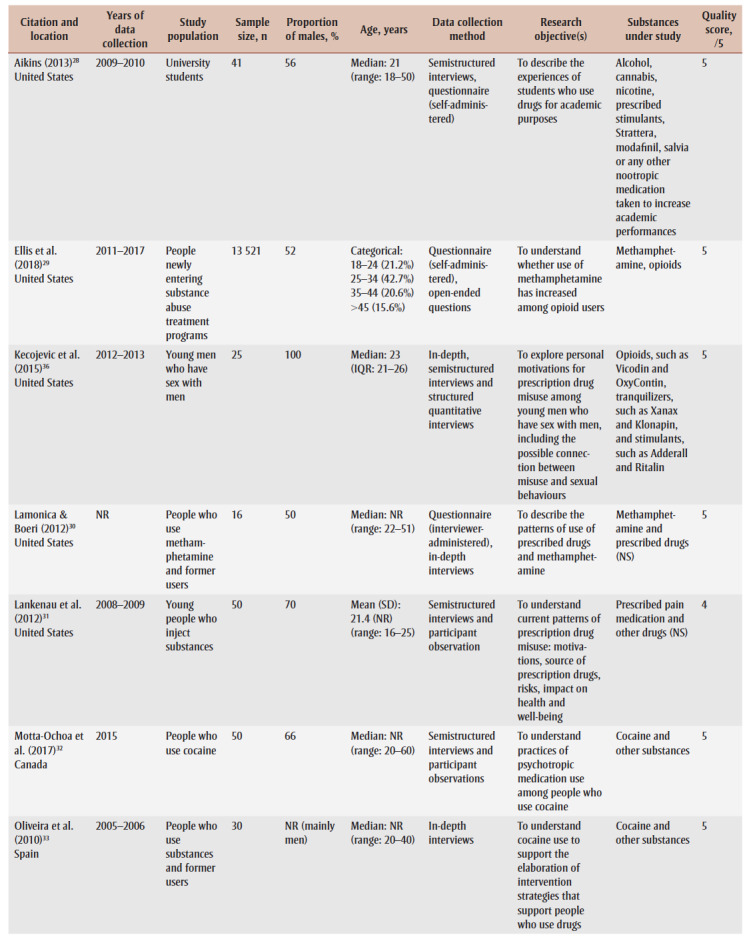

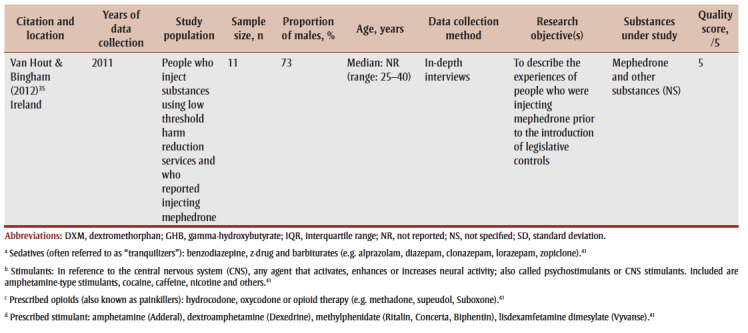

Eleven of the included studies were conducted in North America14,28-30,32,34,36-40 and two in Europe.33,35 Six were qualitative and 7 were mixed methods studies. The characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table1.

Table 1. Summary of included studies reporting on polysubstance use, 2010–2021.

|

We classified nine of the studies as high quality. Four mixed-methods studies were considered moderate quality, either because they did not provide a clear rationale for using mixed methods or because the quality of the quantitative and/or qualitative research methods could not be assessed based on the reported information.

The median number of participants in the selected studies was 45, with the actual number between 11 and 13521. The study population was categorized into one of the six following groups: people who attend parties and raves and go to bars; people attracted to the same sex; people attending academic or training institutions; people who inject substances and/or are street involved and/or experiencing homelessness; and people who use substances not otherwise specified.

Ten of the 13 studies were conducted with street-based or socially marginalized populations including people who inject drugs, use harm reduction services or are experiencing homelessness.14,29,30,32,33,35,37-40 The age range varied across the studies, with the overall range 18 to 60 years.

One study examined the reasons for polysubstance use in a population of university students (median of 21 years of age)28; one examined the reasons for polysubstance use among people attracted to the same sex (median of 23 years of age)36; and one examined the reasons for polysubstance use among people who discuss substance use in online forums (mean of 23 years of age)34. Most of the study participants (50–100%) identified as male.

Patterns and motivations for combining substances

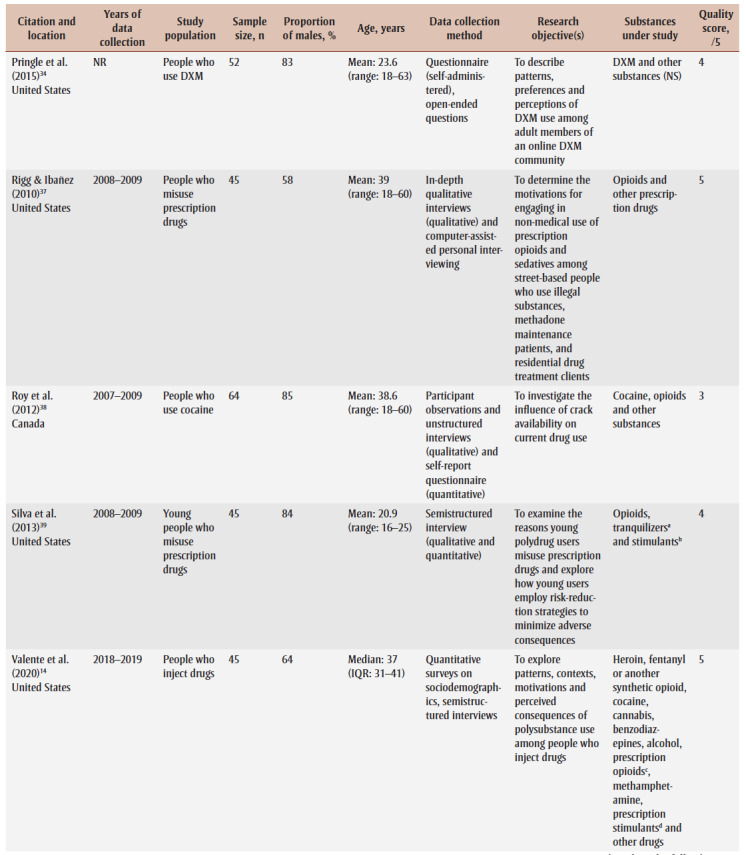

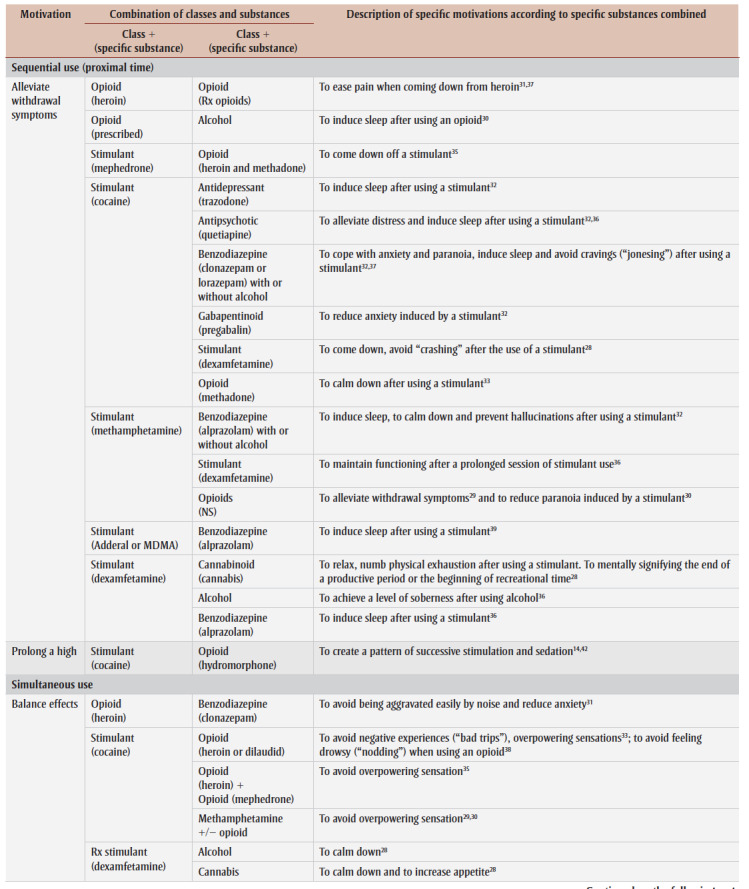

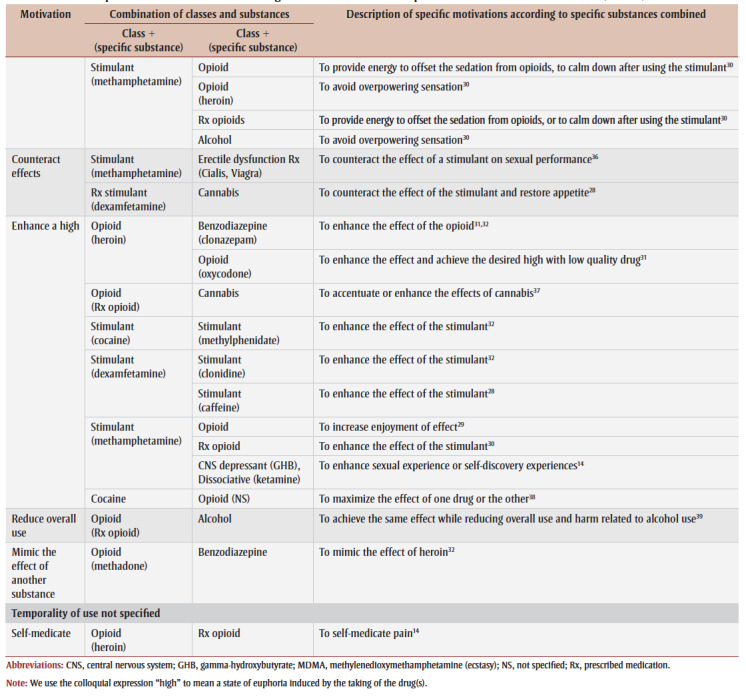

The 13 studies included in this rapid review reported a total of 41 different combinations of substances and the motivations for combining substances (Table 2).

Table 2. Specific motivations for combining substances identified in qualitative or mixed-method studies (N = 13).

|

We found eight motivations for which we described the temporal patterns of use (simultaneous or sequential) when information was available. Excerpts of quotes from the original studies are duplicated here to better illustrate individuals’ motivations for combining substances.

Sequential use

Sequential use refers to the consumption of a substance after the peak effect of another substance. People reported using substances sequentially to alleviate withdrawal symptoms or to prolong a state of euphoria, or “high.”

Alleviate withdrawal symptoms

The most frequently reported combinations of substances involve a stimulant with a depressant (e.g. benzodiazepine, alcohol), cannabis or an opioid to either calm down, induce sleep, alleviate anxiety or distress or avoid drug cravings28,32,35,37,39 produced by the stimulant.

“Sometimes when you do cocaine, or you get really wired up on the Oxys, we need something to come down, and we would take that Xanax to come down or get some sleep because sometimes in the process of doing these drugs you forget to sleep for a couple of days, and then finally you’ve got to say, ‘Okay, it’s time to sleep.’37

Studies reported people using substances within the same class of effect to ease off the effects of the drug. For example, a prescribed stimulant (dexamfetamine) was used to maintain normal functioning after a prolonged session of methamphetamine36 or cocaine28. Similarly, oxycodone was used to ease the pain of heroin withdrawal.37,40

“I kind of like to ride like a stimulant wave, it’s very typical for me to after doing crystal all weekend to just do Adderall, to get through the day. Because, again, you’re not kind of cranky, you’re still up and you’re still awake, and you’re not tired, and you’re able to do super-human things by just keeping going.”36

“… Hey, if you’re sick, what will help is the Percocet. (…) the withdrawals make me feel really shitty. You know? But the Percocet, it kind of takes away all that. So that’s why I use it…I only use it because I will go through withdrawals from the heroin, so I use the Percocet to ease the pain when I can’t get heroin.”37

Prolong a high

The pattern of stimulation sedation can take place in a single day or for longer periods (several days) with stimulants and opioids to prolong a high.14,38

“I would smoke crack and use heroin or fentanyl, what we call landing gear, to come back down. And once you get down, then you’ll want to take another hit [of crack] to go back up, and it’s just like a cat chasing its tail. It never ends. Go up just to come down, then go up [again].”14

Simultaneous use

Simultaneous use is defined here as the consumption of two or more substances at the same time or close in time. The intention of simultaneous use is usually to balance or counteract the effects of one substance by using another substance, to enhance a high, to reduce overall use or to mimic the effect of another substance.

Balance effects

Substances with opposing psychoactive effects were used simultaneously to achieve a desired mental state or to temper undesirable effects. For example, heroin is used to avoid experiencing negative overpowering feelings when using a stimulant.33

“... you no longer think about hallucinations, paranoia, you don’t go through a bad trip, it [simultaneous use of heroin and crack cocaine] is the best thing to reduce the effect.”33

Similarly, a stimulant is used to avoid feeling drowsy when using an opioid or as a depressant.30,38

“I’ll take Adderall mainly when I go to the clubs. At nighttime when I’m too drunk, I’ll take the Adderall to straighten me up a little bit, open my eyes, be more attentive.”36

Counteract effects

Substances with complementary effects can be used simultaneously to counteract undesired effects. For example, erectile dysfunction medication is used to counteract the effect of methamphetamine on sexual performance,36 and cannabis is used to increase appetite when using a stimulant.28

“I smoke the weed to control [the Adderall]. If I get too jittery—too uppity—and I’m grinding [my teeth] way too much, okay, I need to smoke to calm down some, and let myself know I got to eat something.”28

Enhance a high

Motivations for polysubstance use included combining drugs to create synergistic psychoactive effects with the intent to potentiate or enhance the effects of another substance. Often, stimulants are used in combination to increase a high.28,32 People also reported using benzodiazepines31,32 or prescription opioids31 with heroin for the same purpose. Opioids and stimulants were also used in combination to maximize the effect of one drug or the other and create a synergy.38 Substances may also be combined with the specific purpose of enhancing the effect of a low quality drug to achieve the desired high.

“For crappy dope, I’m gonna try to get some Oxys for free, take those, and do a shot of dope. Or, I’ll take a Percocet, start feeling that, and then do a shot of dope, which just intensifies it.”31

Stimulants are combined simultaneously with GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) and ketamine for added pleasure and to enhance sexual experiences or self-discovery.14

“But then [if] you want to go voyaging off into the universe, do a shot of crystal [crystal meth] and special K [ketamine] in the same shot. It’s amazing … I don’t know how to explain it. I feel like I’ve learned a lot about life in those kinds of experiences.”14

Reduce overall use

Substances can be used simultaneously as a harm reduction strategy to decrease substance consumption. For example, alcohol is used with an opioid to achieve the same effect of alcohol while reducing overall intake.39

“It’s usually like, ‘Oh, we’re going out to the bar, OK, I’ll take half a Vicodin and have a couple of drinks, because it makes it that much more intense without having to consume as much.’ [That] is my approach to it. I can go out and have two drinks and take half the Vicodin and feel better than going and having four or five drinks that night.”39

Mimic the effect of another substance

Substances are mixed to help users achieve a desired effect if a preferred substance is not available or only available at a higher price. For instance, participants reported simultaneously using benzodiazepines and methadone to mimic the effects of heroin when that drug is not available.32

“When I take methadone and benzos I nod [laughs] … Nodding is when you are high on heroin. Methadone and benzos make you nod. That’s why some doctors don’t want to prescribe both. It makes the effect of heroin. Methadone and benzos make you high like heroin.”32

Pattern not specified

Self-medicate

Self-medication for poorly managed physical or mental health conditions or to alleviate pain was another common reason for using more than one substance. For instance, a participant described using Suboxone for pain and also self-medicating with a benzodiazepine and Ritalin to cope with a pre-existing condition:

“ [I currently use] Suboxone. I also like to use Xanax [benzodiazepine], it calms me down. The Concerta, the Ritalin [prescription stimulants], gives me energy. I mean, of course, the Suboxone, takes away all the [pain]. ‘Cause I also have chronic pain, and it does help, and that’s mostly (…) just to make it through the day and not be in so much pain.”14

Complex behaviour and superimposed motivations

During a single episode of polysubstance use, there may be multiple motivations that guide the choices of people who use drugs, and drugs may be used both sequentially and simultaneously to meet these goals. For example, the use of alcohol and cannabis often constitute the baseline on which to build the experience, which can then be followed by a simultaneous use of stimulants, psychedelics and a sedative. The following quote exemplifies a situation where a person combines a stimulant and a gabapentinoid to prolong a high and to alleviate negative symptoms:

“Sometimes I do Lyricas [pregabalin], I sniff them…the pills, after I do coke. It is a downer and the other, the coke, is an upper… I want Lyrica just to keep my buzz. [When] I wake up in the morning…I’m good this way, it’s cool, it’s quiet, I’m less anxious.”32

Discussion

We identified and summarized eight motivations of polysubstance use and their temporality of use. Building on previous reviews that looked more widely at polysubstance use,10 our work intentionally puts a narrow focus on overlapping use and described preferred combinations based on the person’s experience and expectations of substance pharmacological effects.

Our results show that there are distinct motivations for using drugs sequentially and simultaneously in a single episode. The use of over five substances in an episode is common and preferred substances vary across groups,14,15,43 making it difficult to capture general patterns of use.

While the object of our review was intentional polysubstance use, we acknowledge that substance combinations are not always a matter of choice. In illicit markets, preferred substances may be contaminated with other substances without the knowledge of the purchaser. In some instances, the progression and maintenance of use happen as a result of dependence, where the use of one substance triggers the use of another.22 Other circumstantial factors can be at play; the emergence of new substances in the illegal local markets, the ease of access to traditional substances and price variations influence patterns of use.44 When a substitute for a drug becomes cheaper, more available or of better quality, people will likely favour it. In North America, the increasing availability and quality of methamphetamine along with its decreased price have led to it being substituted for other stimulants45,46 and to what has been described as the “twin epidemics” of methamphetamine and opioid use.47 A similar pattern is currently being observed in Europe where cocaine quality and affordability have been steadily increasing and so has its use.45

The choice of substances that are used in combination also depends on the context in which they are used to fulfill specific functions.44 For example, studies that include people who go to parties and bars tend to report combinations of “club drugs” including ecstasy/MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), amphetamines, ketamine, cocaine, GHB, psychedelics, cannabis and alcohol.43,48,49 Club drugs are used to increase feelings of euphoria, desirability, self-insight and sociability.50 In other cases, substance combinations can involve non-psychoactive substances that are used to improve the overall experience. For example, a beta blocker can be used to offset tachycardia or omeprazole to avoid stomach pain when using stimulants.7 Studies that focus on people who are attracted to the same sex often describe the use of wide combinations of club drugs15,51 along with erectile dysfunction medication and alkyl nitrite (or “poppers”) for sensation seeking, enhancing the sexual experience and fitting in.52 Studies have also examined the use of prescription stimulants to enhance cognitive performance28,53 and prescription drugs, including benzodiazepine and opioids, to alleviate distress among college and university students.54,55

Changes in the legal status of psychoactive substances are also expected to influence people’s behaviour. As a result of legislative changes, the use of synthetic cathinones such as mephedrone, which was very prevalent a few years ago,35 has fallen drastically.7 A similar pattern of substitution has been observed for fentanyl, where traditional opioids such as heroin were successively substituted with fentanyl and fentanyl analogs56 and, more recently, with non-fentanyl analogs, with effects similar to fentanyl, and analogs such as the nitazenes.57 Designer benzodiazepines such as etizolam are increasingly used as a replacement for their traditional counterparts.58 These changes in the market are expected to be reflected in substance combinations.

While the effects of the new combinations of emerging substances are often unpredictable, analogs are designed to provide legal alternatives to controlled substances and often have similar effects.7 Furthermore, the motivations for using and combining new substances remain similar to their classical counterparts;59 hence the relevance of characterizing and monitoring typical patterns of polysubstance use based on the preferences of people who choose to combine substances.

Strengths and limitations

An important strength of this rapid review is its focal and targeted scope. We reviewed evidence on an explicit and narrow definition of polysubstance use, which allows for a better understanding of combinations potentially involved in acute toxicity events. We defined an episode within a period of 24 hours, but we acknowledge that an episode of use can take place over several days and even weeks.60 Our review focused on articles published in the last decade to highlight patterns that may underlie the current overdose crisis. Qualitative data allowed us to create a richer portrait by characterizing the motivations for combining substances.

Certain limitations should be acknowledged. All included studies relied on self-reports that can be inaccurate because participants are not always aware of the content of a product, especially when using illegal substances.61 We did not explore the mode of substance use, although this could be a determinant of expected effect. Furthermore, some relevant studies may not have been identified by our search strategy given the broad nature of the concept of polysubstance use; thus the combinations reported only represent an overview.

The context in which people use substances is known to influence their behaviour,44 but published information on different settings with patterns of polysubstance use is limited. Finally, while no studies were excluded on the basis of sex/gender or identity of participants, the included work does not reflect the broad scope and diversity of experiences lived by people who use drugs.

Conclusion

While contextual factors such as changes in the illegal drug supply and availability of substance remain major drivers of behaviour, individual motivations significantly affect patterns of use. Putting a greater emphasis on the reasons why people choose to combine substances is a key factor in understanding polysubstance use patterns associated with higher risks of overdose. In doing so, we can better tailor harm reduction messaging to the complex reality of people who use substances.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dominique Parisien, Amanda VanSteelandt, Margot Kuo, Sarah McDougall and Noushon Farmanara from the Public Health Agency of Canada for their assistance with protocol development and content review. We would also like to thank Lynda Gamble and Tanya Durr from the Public Health Agency of Canada Library, Ottawa, for their valuable assistance in the development of the search strategy.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

MBF – conceptualization of search strategy, screening of identified works for inclusion, data extraction, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation

GC – data extraction, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation

GG – data extraction, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation

CL – review of search strategy, screening of identified works for inclusion, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Grant BF, Harford TC, et al. Concurrent and simultaneous use of alcohol with sedatives and with tranquilizers: results of a national survey. J Subst Abuse. 1990;2((1)):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(05)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen P, O’Gorman A, Lamy F, Kataja K, et al. (Re)conceptualizing “polydrug use”: capturing the complexity of combining substances. Hakkarainen P, O’Gorman A, Lamy F, Kataja K. 2019;46((4)):400–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tori ME, Larochelle MR, Naimi TS, et al. Alcohol or benzodiazepine co-involvement with opioid overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. Tori ME, Larochelle MR, Naimi TS. 2020;3((4)):e202361–17. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Valentino RJ, DuPont RL, et al. Polysubstance use in the U.S. Mol Psychiatry. 2021:41–50. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00949-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppin JF, Raffa RB, Schatman ME, et al. The polysubstance overdose-death crisis. J Pain Res. 2020:3405–8. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S295715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, et al. Polysubstance use: a broader understanding of substance use during the opioid crisis. Am J Public Health. 2020;110((2)):244–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidance on the management of acute and chronic harms of club drugs and novel psychoactive substances. Abdulrahim D & Bowden-Jones O; NEPTUNE Expert Group. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Opioid-and stimulant-related harms in Canada (September 2021) [Internet] Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants. [Google Scholar]

- Lin LA, Bohnert AS, Blow FC, et al, et al. Polysubstance use and association with opioid use disorder treatment in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction. 2021;116((1)):96–104. doi: 10.1111/add.15116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JP, Gullo MJ, White A, Kelly AB, et al. Polysubstance use: diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014:269–75. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA. Lisbon(PT): 2012. The state of the drugs problem in Europe: annual report 2012. [Google Scholar]

- n F, Cleland CM, Palamar JJ, et al. Polysubstance use profiles among electronic dance music party attendees in New York City and their relation to use of new psychoactive substances. Addict Behav. 2018:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting AM, Oser C, Staton M, Knudsen H, et al. Polysubstance use patterns among justice-involved indivi-duals who use opioids. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55((13)):2165–74. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2020.1795683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente PK, Bazzi AR, Childs E, et al, et al. Patterns, contexts, and motivations for polysubstance use among people who inject drugs in non-urban settings in the U.S. Int J Drug Policy. 2020:102934–74. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G, Wall MM, Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, et al. Complex drug use patterns and associated HIV transmis-sion risk behaviors in an Internet sample of U.S. Arch Sex Behav. 2015:421–8. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckermann AM, Williams GC, Battista K, Jiang Y, Groh M, Leatherdale ST, et al. Prevalence and corre-lates of youth poly-substance use in the COMPASS study. Addict Behav. 2020:106400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Buxton JA, et al. Pathways between COVID-19 public health responses and increasing overdose risks: a rapid review and conceptual framework. Int J Drug Policy. :103236–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gili A, Bacci M, Aroni K, et al, et al. Changes in drug use patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: monitoring a vulnerable group by hair analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18((4)):1967–8. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis JV, Darredeau C, Barrett SP, et al. Substance use initiation: the role of simultaneous polysubstance use; 22612987. Substance use initiation: the role of simultaneous polysubstance use; 22612987. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenz RC, Scherer M, Harrell P, Zur J, Sinha A, Latimer W, et al. Early onset of drug and polysubstance use as predictors of injection drug use among adult drug users. Addict Behav. 2012;37((4)):367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell BS, Trudeau JJ, Leland AJ, et al. Social influence on adolescent polysubstance use: the escalation to opioid use. Subst Use Misuse. 2015:1325–31. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1013128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crummy EA, O’Neal TJ, Baskin BM, Ferguson SM, et al. One is not enough: understanding and modeling polysubstance use. Front Neurosci. 2020:569–31. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataja K, Hakkarainen P, Vayrynen S, et al. Risk-taking, control and social identities in narratives of Finnish polydrug users. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2018:457–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins M, et al. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Hamilton(ON): Rapid review guidebook [Internet] Available from: https://www.nccmt.ca/tools/rapid-review-guidebook. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AJ, Farmer EJ, Finn PR, et al. Patterns of polysubstance use and simultaneous co-use in high risk young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019:107656–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong QN, Gonzalez-Reyes A, Pluye P, et al. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) J Eval Clin Pract. 2018:459–67. doi: 10.1111/jep.12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikins R, et al. Academic performance enhancement drugs in higher education [Dissertation] University of California. 2012 Available from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED548936. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, Cicero TJ, et al. Twin epidemics: the surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamonica AK, Boeri M, et al. An exploration of the relationship between the use of methamphetamine and prescription drugs. J Ethnogr Qual Res. 2012;6((3)):160–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Bloom JJ, Harocopos A, Treese M, et al. Patterns of prescription drug misuse among young injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2012;89((6)):1004–16. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9691-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta-Ochoa R, Bertrand K, Arruda N, Jutras-Aswad D, et al. “I love having benzos after my coke shot”: the use of psychotropic medication among cocaine users in downtown Montreal. Int J Drug Policy. 2017:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira LG, Ponce JC, Nappo SA, et al. Crack cocaine use in Barcelona: a reason of worry. Subst Use Misuse. 2010:2291–300. doi: 10.3109/10826081003682883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle G, McDonald MP, Gabriel KI, et al. Patterns and perceptions of dextromethorphan use in adult members of an online dextromethorphan community. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015:267–75. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2015.1071448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hout MC, Bingham T, et al. “A costly turn on”: patterns of use and perceived consequences of mephedrone based head shop products amongst Irish injectors. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23((3)):188–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kecojevic A, Corliss HL, Lankenau SE, et al. Motivations for prescription drug misuse among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in Philadelphia; 25936445. drugpo. 2015;26((8)):764–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg KK, ez GE, et al. Motivations for non-medical prescription drug use: a mixed methods analysis; 20667680. jsat. 2010;39((3)):236–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Arruda N, Vaillancourt E, et al, et al. Drug use patterns in the presence of crack in downtown Montral. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31((1)):72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva K, Kecojevic A, Lankenau SE, et al. Perceived drug use functions and risk reduction practices among high-risk nonmedical users of prescription drugs. J Drug Issues. 2013;43((4)):483–96. doi: 10.1177/0022042613491099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Bloom JJ, Harocopos A, Treese M, et al. Patterns of prescription drug misuse among young injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2012;89((6)):1004–16. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9691-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- rd ed, et al. Laboratory and Scientific Section. Terminology and information on drugs. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Richer I, Arruda N, Vandermeerschen J, Bruneau J, et al. Patterns of cocaine and opioid co-use and polyroutes of administration among street-based cocaine users in Montral, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24((2)):142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SP, Gross SR, Garand I, Pihl RO, et al. Patterns of simultaneous polysubstance use in Canadian rave attendees. Subst Use Misuse. 2005:1525–37. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakula B, Macdonald S, Stockwell T, et al. Settings and functions related to simultaneous use of alcohol with marijuana or cocaine among clients in treatment for substance abuse. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44((2)):212–26. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Vienna(AT): World Drug Report 2020: Booklet 3; pp. Booklet 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Compton WM, Mustaquim D, et al. Patterns and characteristics of methamphetamine use among adults – United States, 2015–2018. Jones CM, Compton WM, Mustaquim D. 2020;69((12)):317–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, Havens JR, Stoops WW, et al. A nationally representative analysis of “twin epidemics”: rising rates of methamphetamine use among persons who use opioids. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019:107592–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht CL, Christoffersen M, Okholm M, et al, et al. Simultaneous polysubstance use among Danish 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and hallucinogen users: combination patterns and proposed biological bases. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012;27((4)):352–63. doi: 10.1002/hup.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- n F, Lozano OM, Vidal C, et al, et al. Polysubstance use patterns in underground rave attenders: a cluster analysis. J Drug Educ. 2011;41((2)):183–202. doi: 10.2190/DE.41.2.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogt TF, Engels RC, et al. “Partying” hard: party style, motives for and effects of MDMA use at rave parties. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40((9-10)):1479–502. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Mattison AM, Franklin DR, et al. Club drugs and sex on drugs are associated with different motivations for gay circuit party attendance in men. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38((8)):1173–83. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgetti R, Tagliabracci A, Schifano F, Zaami S, Marinelli E, Busardo FP, et al. When “chems” meet sex: a rising phenomenon called “chemsex”. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15((5)):762–70. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666161117151148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Knight JR, Teter CJ, Wechsler H, et al. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction. 2005;100((1)):96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt SA, Taverna EC, Hallock RM, et al. A survey of nonmedical use of tranquilizers, stimulants, and pain relievers among college students: patterns of use among users and factors related to abstinence in non-users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143((1)):272–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, West BT, Teter CJ, McCabe SE, et al. Prevalence and correlates of co-ingestion of prescription tranquilizers and other psychoactive substances by U.S. Addict Behav. 2016:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamouzian M, Papamihali K, Graham B, et al, et al. Known fentanyl use among clients of harm reduction sites in British Columbia, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2020:102665–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanckaert P, Cannaert A, Uytfanghe K, et al, et al. Report on a novel emerging class of highly potent benzimidazole NPS opioids: chemical and in vitro functional characterization of isotonitazene. Drug Test Anal. 2020:422–30. doi: 10.1002/dta.2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namara S, Stokes S, Nolan J, Med J, et al. The emergence of new psychoactive substance (NPS) benzodiazepines. Ir Med J. 2019;112((7)):970–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettner H, Mason NL, Kuypers KP, et al. Motives for classical and novel psychoactive substances use in psychedelic polydrug users. Contemp Drug Probl. 2019;46((3)):304–20. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A, Scott N, Dietze P, Higgs P, Reduct J, et al. Motivations for crystal methamphetamine-opioid co-injection/co-use amongst community-recruited people who inject drugs: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17((1)):14–20. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- m M, Pelander A, Simojoki K, et al. Patterns of drug abuse among drug users with regular and irregular attendance for treatment as detected by comprehensive UHPLC-HR-TOF-MS. Drug Test Anal. 2016:39–46. doi: 10.1002/dta.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]