Abstract

A new set of mutations, including transposition of the insertion sequence IS6110, was identified in the pncA gene from 19 pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Alignment of the PncA protein from M. tuberculosis with homologous proteins from different bacterial species revealed three highly conserved regions in PncA which may play an important role in the processing of pyrazinamide.

Recently, the gene pncA, encoding the pyrazinamidase (PZase) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, was identified (8); mutations in pncA have been shown to be associated with pyrazinamide (PZA) resistance (1, 5, 9, 10). However, the mutations found in the amino acid sequence of the PZase from M. tuberculosis have not been investigated with respect to their locations in conserved regions which may have an important catalytic function in the enzyme. In this study, we present an analysis of the sequence of the pncA gene from 35 epidemiologically unrelated (i.e., with distinct restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns) strains of M. tuberculosis isolated during the last decade in France, and we assess whether the mutations occurred randomly or in particular regions of the PZase.

MICs of PZA were determined at two different pH values (5.6 and 5.8), as previously described (8). Among the 35 clinical isolates, 16 were susceptible (MIC ≤50 μg/ml) and 19 were highly resistant (MIC ≥ 500 μg/ml) to PZA. PZase activity tested by the Wayne method (11) showed that all PZA-susceptible (PZA-S) isolates were PZase positive and all PZA-resistant (PZA-R) isolates lacked PZase activity except isolate 9420 (Table 1). Finally, the pncA gene as well as the 105-bp upstream and 60-bp downstream regions were amplified from each strain by using the conditions and the set of primers, P1 and P6, previously described by Scorpio et al. (9). The nucleotide sequences of the PCR products were generated with an Applied Biosystems, Inc., automatic DNA sequencer (model 377).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of PZA-R clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis

| Strain (year of isolation) | Main associated drug resistancea | PZA MIC (μg/ml)b

|

PZase activity | Variation(s) in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 5.6 | pH 5.8 | Nucleotide sequence | Amino acid sequence | |||

| 2701 (1997) | H R E S | 1,500 | 2,000 | Negative | None | None |

| 8017 (1988) | H R S | 500 | 1,000 | Negative | None | None |

| 7283 (1986) | H R S | 500 | 1,500 | Negative | None | None |

| 7337 (1986) | H R | NG | 1,000 | Negative | G7→C | A3→P |

| 7759 (1987) | H R E S | >2,000 | >2,000 | Negative | T38→C | F13→S |

| 9420 (1992) | H R E S | NG | 500 | Positive | A181→C | T61→P |

| 3303 (1994) | H R | >2,000 | >2,000 | Negative | C206→T | P69→L |

| 2759 (1994) | H R S | NG | 1,000 | Negative | A287→C | K96→T |

| 480 (1994) | H R E | NG | 1,500 | Negative | A308→G | Y103→C |

| 7911 (1987) | H R | >2,000 | >2,000 | Negative | G395→A | G132→D |

| 7508 (1987) | H R E | 1,500 | 1,500 | Negative | T464→G | V155→G |

| 9701 (1997) | H R S | 500 | 2,000 | Negative | T545→C | L182→S |

| 7501 (1987) | H R E | 1,000 | 1,500 | Negative | C260→T and nucleotide G deletion at position 436 | T87→M |

| 2134 (1996) | S | 1,000 | 1,000 | Negative | Nucleotide A insertion at position 192 | |

| 8220 (1989) | H R E S | 500 | 1,500 | Negative | Nucleotide C insertion at position 306 | |

| 7582 (1988) | H R E S | 500 | 1,000 | Negative | Two nucleotide G insertions at position 391 | |

| 9638 (1992) | H R E | NG | 1,000 | Negative | 68-bp deletion at position 419 | |

| 7169 (1986) | H R S | >2,000 | >2,000 | Negative | 29-bp insertion at position 215 | |

| 8250 (1989) | H R E | NG | 1,000 | Negative | 1,355-bp insertion at position 341 | |

H, isoniazid; R, rifampin; S, streptomycin; E, ethambutol.

NG, no growth.

As expected, the 16 PZA-S strains had no detectable mutations and 16 (84%) of the 19 PZA-R isolates harbored mutations in pncA, thus confirming that pncA mutations are the major mechanism of resistance to PZA in M. tuberculosis. The remaining three PZA-R isolates with no mutations in pncA had also no mutations in the putative 105-bp upstream regulatory region. All mutations were new except the G132→D substitution (5). One isolate (8250) harbored a 1,355-bp insertion at position 341 in pncA which generated a duplication of 3 bp, suggesting that this event resulted from a transposition process. This insertion was sequenced by using a second set of primers, Y1 (5′-CTACACCGGAGCGTACAGCG-3′) and Y2 (5′-GGCGCACACAATGATCGGTG-3′), corresponding to nucleotides 294 to 313 and 402 to 421 in pncA, respectively. Comparison of the sequence obtained with those contained in the GenBank database revealed that it corresponded to the nucleotide sequence of IS6110. To our knowledge, this is the first report of transposition of a complete IS6110 copy in a gene involved in susceptibility to antituberculous drugs. Recent reports have shown that IS6110 transposes preferentially to hot-spot regions such as the direct repeat, ipl, and DK1 loci (2–4). Interestingly, we found that insertion of IS6110 in strain 8250 occurred in a region of 10 bp encompassing nucleotides 337 to 346 in pncA (GGCAC↓GCCAC) which is identical to the region located between nucleotides 382 and 391 in the ipl locus (2).

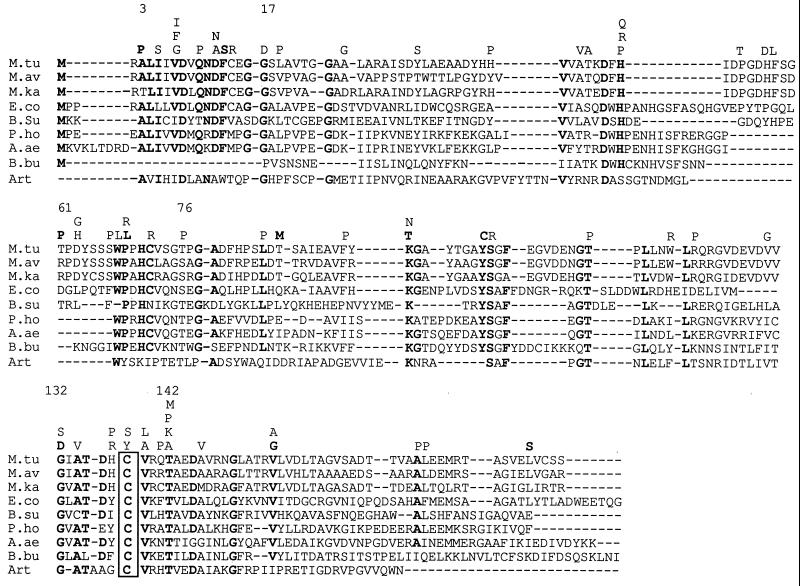

It is generally considered that the mutations leading to PZA resistance are scattered along the pncA gene (6). However, Scorpio et al. (9) mentioned some degree of clustering of mutations in three regions (positions 5 to 12, 69 to 85, and 132 to 142) of the PncA protein among the 26 strains harboring distinct mutations. We analyzed the data presented here together with those previously obtained from strains recovered in North America (8–10), South America (1), and Asia (5) to enhance the number and the geographic diversity of strains. We found that 34 (54%) of the 63 distinct amino acid substitutions reported in the literature occurred preferentially in three distinct regions (positions 3 to 17, 61 to 76, and 132 to 142) that are close to those described by Scorpio et al. (9). These regions represent only 22% of the full length of the PncA protein (Fig. 1). Alignment of the amino acid sequences of PZases from various species reveals that the three regions contain highly conserved residues, thus supporting the idea that these regions could be structurally and/or catalytically important for the activity of the enzyme against PZA. To assess such a hypothesis, the amino acid sequences of the PZases aligned in Fig. 1 were compared with that of the N-carbamoylsarcosine amidohydrolase (CSHase) from Arthrobacter sp., an enzyme for which the three-dimensional structure has been determined and which exhibits an amidohydrolytic function similar to that of the PZase (7). Strikingly, the alignment (Fig. 1) indicates that the region encompassing residues 132 to 142 in the M. tuberculosis PZase includes a perfectly conserved cysteine at position 138 corresponding to the catalytic cysteine found at position 177 in the CSHase (7). In addition, residues Ala-172 and Thr-173 in the CSHase, which may facilitate the addition of the nucleophilic thiol group of Cys-177 to the substrate, are also conserved in most PZases and correspond to residues Ala-134 and Thr-135 in M. tuberculosis. The region from positions 61 to 76 in M. tuberculosis also contains an aromatic residue, Trp-68, which is shared by most PZases and is aligned with the Trp at position 111 in the Arthrobacter CSHase. Interestingly, in the crystal structure of this enzyme, the aromatic residue Trp-111 may define, with other aromatic residues, a hydrophobic pocket in which the substrate could bind. Finally, the region from position 3 to 17 in M. tuberculosis harbors the residue Asp-8, which is also present in the CSHase at position 51. The structural data on the CSHase indicate that the acidic residue Asp-51 may increase the nucleophilicity of Cys-177 (7). Taken altogether, these data suggest that Cys-138, Ala-134, Thr-135, Trp-68, and Asp-8 in the M. tuberculosis PZase could be key residues for hydrolysis of PZA. Consequently, the mutations occurring within or close to the regions containing these residues could result in conformational modifications of the active site of the PZase and, consequently, in a loss of activity, as observed in most of our PZA-R strains. It should be pointed out, however, that some of the mutations leading to PZA resistance are not located within the conserved regions. One can hypothesize that the loss of PZase activity observed in such mutants is likely due to improper folding or instability of the PZase protein.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of the pncA genes from M. tuberculosis (M.tu), Mycobacterium avium (M.av), Mycobacterium kansasii (M.ka), Escherichia coli (E.co), Bacillus subtilis (B.su), Pyrococcus horikoshii (P.ho), Aquifex aeolicus (A.ae), and Borrelia burgdorferi (B.bu) (accession no. U59967, U80820, AF002663, M26934, Z99120, AP000004, AE000717 and AE000785, respectively) and of the sequence encompassing residues 46 to 210 of the N-carbamoylsarcosine amidohydrolase from Arthrobacter sp. (Art) (accession no. P32400). Conserved amino acid residues are shown in boldface type, and the putative active cysteine is boxed. All distinct substitutions leading to PZA resistance are shown above the alignment, with boldface letters for those identified in the present study and lightface letters for those previously reported (1, 5, 8–10).

In conclusion, although the mutations found in pncA are scattered along the gene, the present data and analysis suggest that they occur preferentially in conserved regions of pncA which might be very important for the binding and processing of PZA. Further biochemical and structural studies will be necessary to clarify the structure-function relationships of the corresponding residues in the PZase.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Guillemin for technical support, J. P. Lagarde for assistance with sequencing of pncA, and J. Texier-Maugein for M. tuberculosis isolate 9701.

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (grant CRI 950601), the Association Française Raoul Follereau, and the Association Claude Bernard.

REFERENCES

- 1.Escalante P, Ramaswamy S, Sanabria H, Soini H, Pan X, Valiente-Castillo O, Musser J M. Genotypic characterization of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Peru. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;79:111–118. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang K, Forbes K J. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 preferential locus (ipl) for insertion into the genome. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:479–481. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.479-481.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fomukong N, Beggs M, El Hajj H, Templeton G, Eisenach K, Cave M D. Differences in the prevalence of IS6110 insertion sites in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains: low and high copy number of IS6110. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;78:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(98)80003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermans P W M, Van Soolingen D, Bik E M, De Haas P E W, Dale J W, Van Embden J D A. Insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot-spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2695–2705. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2695-2705.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirano K, Takahashi M, Kasumi Y, Fukasawa Y, Abe C. Mutation in pncA is a major mechanism of pyrazinamide resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;78:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(98)80004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramaswamy S, Musser J M. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;79:3–29. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romao M J, Turk D, Gomis-Ruth F-X, Huber R, Schumacher G, Möllering H, Russmann L. Crystal structure analysis, refinement and enzymatic reaction mechanism of N-carbamoylsarcosine amidohydrolase from Arthrobacter sp. at 2.0 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:1111–1130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91056-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scorpio A, Zhang Y. Mutations in pncA, a gene encoding pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase, cause resistance to the antituberculous drug pyrazinamide in tubercle bacillus. Nat Med. 1996;2:662–667. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scorpio A, Lindholm-Levy P, Heifets L, Gilman R, Siddiqi S, Cynamon M, Zhang Y. Characterization of pncA mutations in pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:540–543. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sreevatsan S, Pan X, Zhang Y, Kreiswirth B N, Musser J M. Mutations associated with pyrazinamide resistance in pncA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:636–640. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wayne L G. Simple pyrazinamidase and urease tests for routine identification of mycobacteria. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;109:147–151. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.109.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]