Abstract

Introduction:

Adherence to cancer prevention recommendations can greatly reduce colorectal cancer risk. This study explored patterns and determinants of adherence to these recommendations by participants (n= 26074) at baseline in a cohort study in British Columbia, Canada.

Methods:

Adherence to five colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours derived from Canadian Cancer Society/World Cancer Research Fund recommendations (nonsmoking, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, alcohol consumption and fruit and vegetable consumption) was measured, and a composite score constructed based on their sum. The definition of secondary prevention adherence was based on the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommendations for colorectal cancer screening.

Results:

Adherence to primary prevention guidelines ranged from 94.8% (nonsmoking) to 44.2% (healthy BMI). Median composite score was 4. Higher composite scores were associated with being female, being married and with a higher educational attainment. Colorectal cancer screening adherence was 62.4%. Older age, chronic conditions, a recent medical examination and higher income were associated with greater odds of adherence to screening.

Conclusion:

Adherence to some colorectal cancer prevention behaviours was high, consistent with findings that British Columbia has low rates of many risky health behaviours. However, there was a clustering of poorer adherence to prevention behaviours with each other and with other risk factors. Screening adherence was high but varied with some sociodemographic and health factors. Future work should evaluate targeted interventions to improve adherence among those in the lowest socioeconomic status and health groups. A better understanding is also needed of the barriers to access and engagement with colorectal cancer screening that persist even in the Canadian public health care system.

Keywords: CRC, lifestyle, screening, health behaviours, guideline adherence

Highlights

Adherence to colorectal cancer primary prevention guidelines ranged from 94.8% to 44.2% according to the targeted behaviours.

Adherence to individual colorectal cancer primary prevention guidelines varied with demographic factors. For example, women were significantly more adherent to nonsmoking, fruit and vegetable consumption and body mass index guidelines, but significantly less adherent to alcohol and physical activity recommendations.

Adherence across all primary prevention recommendations was higher among women, those who were married and those who had more education.

Adherence to screening guidelines was 62.4%.

Older participants, those with chronic conditions, higher income and more recent medical exams were more likely to undertake colorectal cancer screening.

Introduction

In 2019, 26300 Canadians were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, making it the third most common cancer in the country.1 According to the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), over a third of all cancers, including colorectal cancer, are preventable through adherence to healthy behaviours: being physically active, maintaining a healthy body mass index (BMI), avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, and eating a diet high in fruit and vegetables and low in processed and red meat.2 The WCRF developed a set of guidelines to inform cancer primary prevention policy.3 Several other bodies, including the Canadian Cancer Society, have produced similar recommendations.4

Secondary prevention (i.e. screening*) of colorectal cancer has also proved to be effective at reducing colorectal cancer mortality.5 Screening for colorectal cancer in asymptomatic adults through fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) every 2 years or flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years has been shown to reduce mortality by approximately 30% as the disease is identified at an early, more treatable stage.6 The Canadian Taskforce on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) recommends colorectal cancer screening for all average-risk adults between the ages of 50 and 74years using these testing modalities.6 Behaviour is key to the success of screening programs as these require consistent engagement to achieve the high levels of participation necessary for effective population-level prevention and early detection.

Despite the weight of evidence demonstrating the importance of health behaviours in both primary and secondary prevention of colorectal cancer, adherence to health behaviour recommendations is suboptimal. In Canada, only 17.6% of adults met physical activity guidelines in 2015,7 and 15% of the overall population report daily or occasional smoking.8 Direct measurements of BMI in a 2012–2013 national survey found that 62% of Canadians were in either the overweight or obese category,9 and in 2016, between 7.2% and 16.2% of Canadians (depending on the province) exceeded low-risk drinking guidelines.10 The most recent figures from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) also indicate that, depending on the province, between 41.3% and 67.2% of Canadians targeted for colorectal cancer screening adhere to CTFPHC guidelines.11

Given this low adherence to recommendations, public health intervention is needed to reduce colorectal cancer risk and mortality. For interventions to be successful, they must be grounded in an understanding of the target populations. While data concerning patterns and predictors of specific risk factors are important, it is also useful to examine overall lifestyle to generate risk profiles.12

Some research has attempted to generate risk profiles by constructing composite scores based on adherence to multiple individual health behaviours. Through our population cohort-based cross-sectional analysis, we built on this work by examining (1) the prevalence of adherence to individual colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours; (2) overall adherence to colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours; and (3) adherence to colorectal cancer secondary prevention behaviours (i.e. screening guidelines).

We also explored factors associated with these three objectives that would improve the understanding of patterns of adherence to colorectal cancer prevention behaviours in British Columbia, and inform interventions to improve adherence in the province.

Colorectal cancer screening can function as both primary prevention (removal of precancerous polyps) and secondary prevention (removal of adenomas). We use “screening” interchangeably with “secondary prevention” to distinguish between life-long primary prevention behaviours and periodic colorectal cancer screening behaviours, in keeping with how these terms are usually used in the literature.

Methods

Data

We obtained baseline study data from the BC Generations Project (BCGP),13 a regional longitudinal cohort of the Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health (CanPath), Canada’s largest health cohort study.14 Recruitment of 28825 participants to the BCGP occurred between 2009 and 2016, with follow-up planned for 50 years. A questionnaire was administered at baseline, along with self-reported or objective physiological measures and biological samples. Recruitment was restricted to those aged 35 to 69 years, and invitation to participate was via mailed or emailed personal letters. Ethics approval for the analyses reported here was received from the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board (H17-03561). All analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.2.15

Analytic samples

Of the 28825 participants, 2751 were excluded because they had a diagnosis of cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer) recorded on the BC Cancer Registry prior to enrolment. The remaining 26074 were assessed for colorectal cancer prevention behaviour adherence. All dependent variables, and most covariates, had missing data, between 0% (for age and sex) and 20.6% (for BMI). Some observations were missing because participants failing to respond to particular questions. It was unlikely responses were “missing completely at random” and results would be biased if a complete case analysis were performed;16 in addition, a large number of participants (n= 9687) would be excluded.

As “missing at random” was a more plausible assumption in our scenario, we imputed values for missing data on dependent and covariates of interest using a multiple imputation by chained equations (mice) approach.17 A total of 20 imputation datasets was created, with 10 iterations per imputation in line with literature recommendations.18 We estimated the parameters of interest in each imputed dataset individually. The results from these 20 imputed datasets were combined (i.e. pooled) using Rubin’s rules.19 All analyses were performed using the R mice package.20

As dependent variables were imputed, we used a multiple imputation then deletion (MID) approach, as outlined by von Hippel.21 According to the MID approach, all dependent variables are included in the imputation process, but cases with missing outcome data are removed before conducting the pooled analysis. As a result, the number of cases available for regression analysis for each dependent variable differed, ranging from 14583 for colorectal cancer screening to 25746 for nonsmoking. The analysis of the composite score (detailed below) was restricted to cases with outcome data for all five colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours (n= 18233). The analysis of colorectal cancer secondary prevention behaviours was limited to participants meeting colorectal cancer screening criteria with complete colorectal cancer screening data (n= 14583).

Study variables

Primary prevention outcome variables

We reviewed the Canadian Cancer Society and WCRF recommendations for cancer prevention strategies to define the binary outcome variables for adherence to each colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviour (see Table 1), using data from participants with complete data for all primary prevention outcomes.

Table 1. The Canadian Cancer Society and World Cancer Research Fund recommendations on colorectal cancer prevention and translation to adherence score in the BCGP.

|

The definition of adherence to low alcohol consumption was based on average drinks per day and participant sex. The definition of nonsmoking adherence was based on current smoking status; never smokers and past smokers were classed as adherent. The definition of adherence to fruit and vegetable consumption was based on fruit, vegetable and 100% fruit juice consumption daily. BMI adherence was based on health practitioner–measured BMI when available and self-reported BMI otherwise. The definition of physical activity was based on responses to either the short- or long-form International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ),22 depending on which version participants had completed, in metabolic equivalent minutes.

Composite adherence score for colorectal cancer primary prevention outcome variables

We calculated a composite score by summing participant adherence to each of the five individual colorectal cancer primary prevention adherence variables, that is, fruit and vegetable consumption, BMI, alcohol, physical activity and nonsmoking. This was computed using data from participants with complete primary prevention outcome data.

Colorectal cancer secondary prevention outcome variables

Adherence to secondary prevention behaviours was limited to all participants with complete data for colorectal cancer screening who met CTFPHC standard screening criteria. Participants were coded as adherent if they had undergone an FOBT within the previous 2 years or flexible sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy within the previous 10 years. Different versions of the BCGP questionnaire asked about flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy, either separately or as the same item, so we used a combined measure of undergoing either procedure.

Covariates of interest

The variables used to examine adherence to primary prevention behaviours were age, sex, marital status, highest level of education, household income, perceived health, time since last routine medical check-up, family history of colorectal cancer, personal history of colorectal cancer-related conditions, ethnicity and chronic conditions. The same variables were examined for association with secondary prevention (i.e. screening guidelines) adherence with the exception of family history of colorectal cancer and personal history of colorectal cancer-related conditions. Primary prevention behaviours were also examined for association with secondary prevention adherence.

Analysis

For adherence to individual primary prevention behaviours, we compared the characteristics of those with complete data for the outcome variables (n=18233) based on adherence to different behaviours using chi-square tests. Following the MID approach, we conducted multivariable logistic regressions to calculate the association between each covariate of interest and each colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviour. Adjusted linear regression models were also completed for the composite adherence score measure and the covariates.

We used descriptive statistics to examine the characteristics of the sample assessed for colorectal cancer secondary prevention (i.e. screening guidelines; n= 14583). A multivariable logistic regression was conducted for each covariate of interest and colorectal cancer screening.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Colorectal cancer primary prevention sample covariates

Most participants in the sample with complete primary prevention data were women (68.5%), and the mean (SD) age was 55 (8.9) years. The majority (76.8%) were married and White (84.3%) and had post-high school education (81.6%) and an annual household income of CAD 75000 to 150000 (39.8%). The majority (94.4%) described their health as good, very good or excellent. A third of participants (32.7%) reported one chronic condition, and 29.1% had two or more chronic conditions. Over a quarter (28.0%) were overweight, and 15.3% were obese.

Colorectal cancer primary prevention outcomes

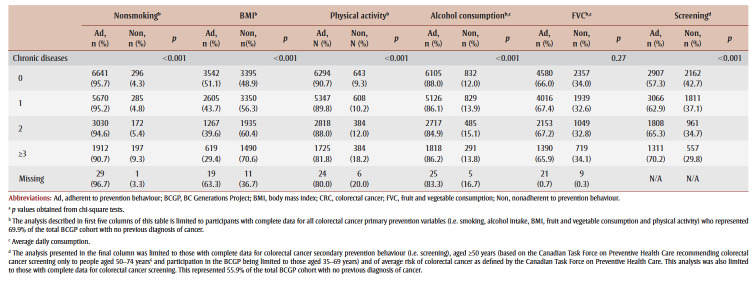

Most participants adhered to primary prevention advice on smoking (94.8%), alcohol (86.6%) and physical activity (88.9%). Adherence to diet and weight–related variables was lower: just 44.2% of participants had a healthy BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), and 66.7% met recommended fruit and vegetable consumption intake guidelines. Many of the demographic and health variables differed significantly between participants who were adherent and nonadherent to colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours (see Table 2).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of BCGP participants compared by adherence and nonadherence to each primary and secondary colorectal cancer prevention behaviour.

Composite colorectal cancer primary prevention adherence score

The median composite score was 4. The mean (SD) value was 3.8 (0.9), and 25% of participants had the maximum score of 5.

Colorectal cancer secondary prevention covariates.

Participants in the colorectal cancer secondary prevention behaviour sample were mostly women (68.0%), and the mean (SD) age was 59 (5.5) years. The majority were married (74.9%) and White (88.1%) and had post-high school education (79.0%). The most common household income range was CAD 75000–150000 (38.8%).

Participants were healthy; 94.2% described their health as good, very good or excellent. Chronic conditions were more common than in the colorectal cancer primary prevention sample; 33.4% of participants reported one chronic condition, and 31.8% had two or more chronic conditions. Nearly a third of participants (28.9%) were overweight and 15.9% were obese (data not shown).

Colorectal cancer secondary prevention outcomes

Adherence to secondary prevention behaviours was 62.4%; 43.4% of participants had undergone an FOBT in the previous 2 years, and 36.4% had undergone a flexible sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy in the previous 10 years (some had undergone both). Many of the demographic and health variables differed significantly between participants who were adherent and nonadherent to the secondary prevention behaviours (see Table 2).

Regression results

Hosmer and Lemeshow tests for each adjusted model of colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours showed that the models were well-calibrated (p-values >0.05) across all imputed datasets. The mean area under the curve (AUC) for each adjusted model across all imputed datasets was between 0.61 (alcohol adherence) and 0.73 (nonsmoking adherence). Most Hosmer and Lemeshow tests (18 across 20 imputed datasets) were nonsignificant for the adjusted secondary prevention behaviour model.

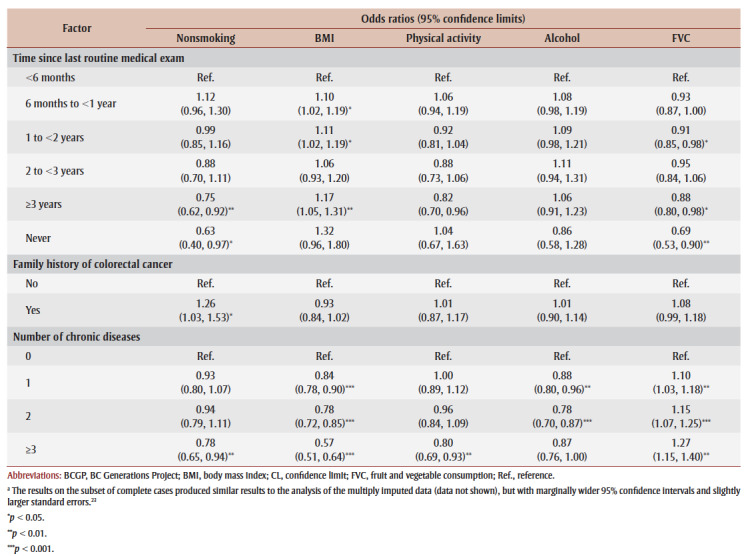

Multivariable modelling of the colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours

Women had higher odds than men of being nonsmokers (1.24; 95% confidence limits [CL]: 1.09, 1.40; p<0.001), achieving recommended fruit and vegetable consumption levels (2.34; 95% CL: 2.21, 2.48; p<0.001) and having a healthy BMI (2.49; 95% CL: 2.33, 2.66; p<0.001). Conversely, women had lower odds of being adherent to alcohol (0.66; 95% CL: 0.60, 0.72; p<0.001) and physical activity (0.88; 95% CL: 0.80, 0.97; p<0.01) recommendations (see Table 3). Higher household income was associated with higher odds of being a nonsmoker and lower odds of BMI and alcohol intake adherence relative to those in the lowest household income category. Higher educational attainment was also associated with higher odds of nonsmoking and adherence to alcohol and fruit and vegetable consumption guidelines relative to those with an elementary school education or less. Multimorbidity was associated with lower odds of BMI adherence, and family history of colorectal cancer was associated with higher odds of being a nonsmoker (1.26; 95% CL: 1.03, 1.53; p<0.05) relative to those with no such history (see Table 3).

Table 3. Association between adherence to colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours and potential predictors in the BCGP.

|

Modelling composite scores

The composite score for women was 0.34 points higher (95% CL: 0.32, 0.37; p<0.001) than for men (see Table 4). Unmarried participants had composite scores 0.08 points lower (95% CL: −0.12, −0.05; p<0.001) than married participants. Composite adherence score increased with educational attainment and perceived healthiness. Those who self-reported excellent health had composite scores 0.93 points higher (95% CL: 0.77, 1.08; p<0.001) than those in poor health. Similarly, multimorbidity was associated with lower composite scores relative to those with no chronic disease.

Table 4. Linear regression associations between the adherence composite score and colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours and potential predictors in the BCGP.

|

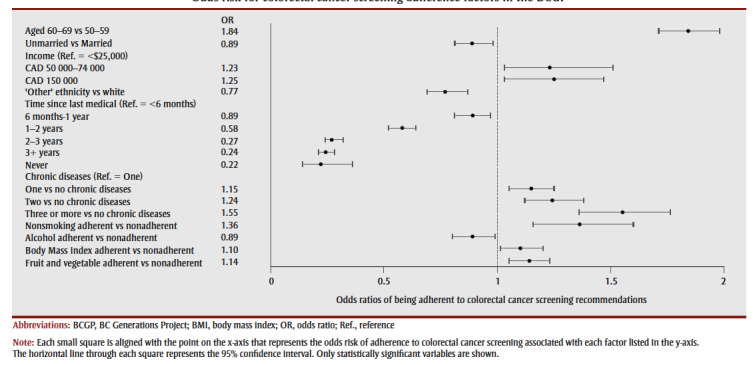

Multivariable modelling of colorectal cancer secondary prevention behaviours

Older participants had significantly higher odds of adhering to colorectal cancer screening guidelines than younger participants (1.84; 95% CL: 1.71, 1.98; p<0.001) (see Figure 1) as did unmarried (0.89; 95% CL: 0.81, 0.98; p<0.01) relative to married participants. Increasing time since last routine medical examination was also associated with lower odds. Multimorbidity was associated with higher odds of adherence to colorectal cancer screening guidelines relative to no chronic disease as was nonsmoking relative to smoking (1.36; 95% CL: 1.16, 1.61; p<0.001) and adherence to fruit and vegetable consumption guidelines (1.14; 95% CL: 1.05, 1.23; p<0.001) compared to being nonadherent.

Figure 1. Odds risk for colorectal cancer screening adherence factors in the BCGP.

Discussion

Research has shown that adherence to WCRF cancer prevention guidelines is inversely associated with cancer risk.24 In this current study, we measured adherence to colorectal cancer prevention guidelines in a British Columbia cohort and examined sociodemographic and health-related correlates of this adherence, both to individual behaviours and combined behaviours. Participants were highly adherent to nonsmoking (94.8%), alcohol consumption (86.6%) and physical activity (88.9%) guidelines, but less likely to adhere to fruit and vegetable consumption recommendations (66.7%) or to have a healthy BMI (44.2%). The composite adherence score indicated good overall adherence by this cohort to Canadian Cancer Society/WCRF guidelines on preventing colorectal cancer.

Comparing these results with those of other studies is complicated by the WCRF guidelines being operationalized in different ways, given the absence of broadly accepted metrics. In addition, this study included nonsmoking as a colorectal cancer prevention behaviour which, while not directly included in WCRF recommendations, is mentioned in the documentation for these guidelines, and is the largest individual preventable cause of cancer.25

One study, by Whelan et al.,26 from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project (a regional cohort within CanPath)14 reported a similar mean (SD) composite score (3.3 [1.2]), but operationalized seven variables, indicating lower overall adherence than in our British Columbia analysis.26 Adherence to alcohol guidelines was similar to our results (88%), but physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption adherence was lower, at 48% and 35–44% (depending on sex), respectively. Adherence to BMI was closer to our findings (23% for men and 40% for women).

Jung et al.27 reported lower BMI adherence levels in an older cohort, although they operationalized adherence as having a normal BMI throughout adulthood. At 90.8% for men and 94.2% for women, alcohol adherence was similar to our findings. In contrast, they reported lower physical activity adherence (26.2% for men and 18.4% for women), which may be because of the higher mean age of the study participants (74.5 years) than in our cohort.27 They also reported lower overall mean (SD) composite score relative to the seven guidelines they operationalized (men: 3.24 [1.10]; women: 3.17 [1.10]).27

In keeping with the literature, greater perceived and actual health in our analysis were also strongly associated with higher composite score. It was also those with the lowest perceived health who were least likely to be adherent to individual colorectal cancer primary prevention behaviours. Individual behaviour adherence varied by sex, with women significantly more adherent to nonsmoking, fruit and vegetable consumption and BMI guidelines, but significantly less adherent to alcohol and physical activity recommendations. Research generally finds that women consume less alcohol than men,28 but these results suggest women may be drinking more relative to their “safe” levels.

Finally, family history of colorectal cancer was associated with higher odds of being a nonsmoker. Given the increased risk for those with a family history of the disease29 and for smokers30, perhaps participants who are at an increased risk are taking action to reduce their risk in controllable domains.

The relative importance of individual components is important to recognize in consideration of the composite score. For example, studies examining prevention guideline adherence have consistently reported nonsmoking, followed by BMI and diet-related factors, to be a stronger predictor of mortality outcome than any other lifestyle factor.24 The varying impact of each guideline on risk suggests it may be appropriate to weight each and derive a composite score attuned to the specific risk for each lifestyle factor. Such a task would be complex and further complicated by considering specific cancer sites, for example, appropriate weighting of guidelines might be subtly, but importantly, different for CRC relative to lung cancer.

Adherence to colorectal cancer screening in this cohort (62.4%) was much higher than the most recently available Canada-wide administrative data (23%).31 This may be, in part, because these Canada-wide data were from 2012, when many provincial colorectal cancer screening programs were in their infancy or non-existent. In British Columbia, such a program was not established until 2013.

The high colorectal cancer screening rates reported here may also be because we combined flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy assessments. Indeed, the 2012 CCHS found similar levels of screening adherence (55.2%) using the same definition of screening adherence (i.e. FOBT and/or either flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy).11 This is a limitation, as colonoscopy is not routinely recommended for screening in British Columbia, and some of the participants who were defined as adherent because they had had a colonoscopy had done so for diagnostic reasons. However, the proportion of participants adherent to FOBT alone was still high (43.4%). Limiting the screening dataset to participants at average risk of colorectal cancer also improves the accuracy of this measure: only those participants who met the CTFPHC guidelines were included.

The assessment of predictors of colorectal cancer screening adherence in this cohort identified some potentially important factors in guiding future colorectal cancer screening interventions. Older participants were more likely to adhere to screening guidelines. This has also been reported by Singh et al.11 and Wong et al.,32 and suggests participants may be delaying screening. Alternatively, older participants may be more likely to have undergone flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy for non-colorectal cancer screening reasons. In addition, contact with the health care system may be an important screening determinant; participants had lower odds of being adherent the longer it had been since their last routine medical examination. Relatedly, those with chronic conditions were more likely to be adherent, perhaps reflecting their more regular contact with health care professionals.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the large sample size and the availability of detailed information on both colorectal cancer primary and secondary prevention behaviours. However, the available data did not provide all the information required for the full operationalization of all WCRF cancer prevention recommendations. This reduces the validity of the current scoring system. In addition, response bias is possible in the available data given the self-report nature of most measures, that is, healthy behaviours may be overreported and unhealthy behaviours underreported. The cross-sectional nature of the data also disallows assessment of the impact of adherence on cancer incidence, although because the BCGP is an ongoing longitudinal cohort, these outcomes could be assessed in the future.

The high levels of perceived good health support a volunteer effect in this study. For example, participants in this study had smoking levels almost one-third of those reported in a recent national survey (5.2% versus 13%).33 Part of this difference is likely because participants were residents of British Columbia; in the same survey British Columbians had the joint lowest level of smoking prevalence among adults in Canada (10%). The remainder may be attributed to participants in the BCGP being more likely to be adherent to health behaviour recommendations, which means the results reported here must be interpreted with caution. In terms of health status, a recent cohort profile of BCGP found higher proportions of some chronic conditions compared to CCHS participants of the same age.13 Differences between BCGP participants and the general British Columbia population (35–69 years) included participants being more likely to be highly educated, female and Canadian or British born.13 The trends in our analytic sample were the same. These limitations, in addition to those to do with healthy volunteer effect, reduce the generalizability of our results, in particular to underrepresented groups such as immigrants and those living at lower socioeconomic status.

Conclusion

This study found high levels of adherence to some colorectal cancer prevention behaviours. While this may be partially explained by a healthy volunteer effect, given the contrast in results to those from other similar cohorts, it is likely more reflective of the general healthy lifestyle of British Columbia residents. Research has consistently found that British Columbia has the lowest rates of some risky health behaviours and chronic diseases,33 and the highest rates of health-protective behaviours such as physical activity. This study supports these findings in the domain of colorectal cancer prevention and highlights the need for further research to understand British Columbia’s successes to enable their translation to other Canadian provinces.

The results also suggest a clustering of poorer adherence to colorectal cancer primary and secondary prevention behaviours with each other and with other risk factors. For example, indicators of lower socioeconomic status such as low household income and educational attainment were associated with increased smoking and lower colorectal cancer screening adherence. Similarly, lower educational attainment was associated with lower composite score. To address this finding, policy could be used to make free weight-loss support and cheaper healthy food choices available to groups living at lower socioeconomic status. Research could help ensure any such policy was tailored to the needs and preferences of target groups.

Finally, adherence to colorectal cancer screening guidelines was high relative to Canadian screening targets, but almost a third of participants were not being screened as recommended, despite this sample likely being more health conscious than the general population. Further research should build on the analysis presented here to identify more specific targetable populations for prevention interventions. Future work in this cohort can also examine the impact of adherence to cancer prevention guidelines on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality as well as other disease outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The data used in this research were made available by the BC Generations Project (BCGP), part of the Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health (CanPath). BC Generations is hosted by BC Cancer. BC Generations received financial support from the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer and from Health Canada. BCGP has also been supported by the BC Cancer Foundation.

We thank the BC Generations data manager and research manager for their support providing the data for this study.

Conflicts of interest

Over the past 2 years, MEK has received consulting fees from Biogen Inc. for projects unrelated to this research and manuscript.

The rest of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

MSM – Conceived and designed the study, conducted the analysis, compiled the results, wrote the manuscript.

CG – Provided critical feedback on the conception and design of the study, contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

MEK – Provided critical feedback on the design of the methods and analysis, contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

JT – Provided critical feedback on the conception of the study, contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

TD – Provided critical feedback on the conception and design of the study, facilitated acquisition of the data, contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

The views expressed represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Canada.

References

- Canadian Cancer Society. Toronto(ON): Canadian Cancer Statistics 2019 [Internet] Available from: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2019-statistics/canadian-cancer-statistics-2019-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- American Institute for Cancer Research. Washington(DC): Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective: the third expert report [Internet] Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/diet-and-cancer. [Google Scholar]

- Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Recommendations.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Toronto(ON): Reduce your risk: make healthy choices [Internet] Available from: https://www.cancer.ca/en/prevention-and-screening/reduce-cancer-risk/make-healthy-choices/?region=bc. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L, et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103((6)):1541–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care. CMAJ. 2016;188((5)):340–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Household population meeting/not meeting the Canadian physical activity guidelines, inactive [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1310033701. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS): summary of results for 2017 [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2017-summary.html. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadian Health Measures Survey: household and physical measures data, 2012 to 2013 [Internet] Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/141029/dq141029c-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Toronto(ON): 2018 cancer system performance report [Internet] Available from: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/2018-cancer-system-performance-report/ [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Bernstein CN, Samadder JN, Ahmed R, et al. Screening rates for colorectal cancer in Canada: a cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3((2)):E149–57. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler LN, Garcia DO, Harris RB, Oren E, Roe DJ, Jacobs ET, et al. Adherence to diet and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines and cancer outcomes: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016:1018–28. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla A, McDonald TE, Gallagher RP, et al, et al. Cohort profile: The British Columbia Generations Project (BCGP) Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48((2)):377–78k. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borugian MJ, Robson P, Fortier I, et al, et al. The Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project: building a pan- Canadian research platform for disease prevention. CMAJ. 2010;182((11)):1197–201. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna(AT): 2019. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009:b2393–201. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexible imputation of missing data. Buuren S van. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- White IR, Royston P, Wood AM, et al. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30((4)):377–99. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB, et al. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken(NJ): 1987. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K, in R, et al. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45((1)):1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hippel PT, et al. 4. Sociol Methodol. 2007;37((1)):83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, m M, et al, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35((8)):1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhlila DS, Sellaouti F, et al. Multiple imputation using chained equations for missing data in TIMSS: a case study. Large Scale Assess Educ. 2013:4–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat GC, Matthews CE, Kamensky V, Hollenbeck AR, Rohan TE, et al. Adherence to cancer prevention guidelines and cancer incidence, cancer mortality, and total mortality: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015:558–69. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.094854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon JS, Winskell K, McFarland DA, Rio C, et al. A case-based, problem-based learning approach to prepare master of public health candidates for the complexities of global health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105((Suppl 1)):S92–96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan HK, Vaseghi S, Siou G, McGregor SE, Robson PJ, et al. Alberta’s Tomorrow Project: adher-ence to cancer prevention recommendations pertaining to diet, physical activity and body size. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20((7)):1143–53. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016003451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung AY, Miljkovic I, Rubin S, et al, et al. Adherence to cancer prevention guidelines among older white and black adults in the Health ABC Study. Nutrients. 2019;11((5)):1008–53. doi: 10.3390/nu11051008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T, Chapman C, Swift W, Keyes K, Tonks Z, Teesson M, et al. Birth cohort trends in the global epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol-related harms in men and women: systematic review and metaregression. BMJ Open. 2016;6((10)):e011827–53. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery JT, Ahnen DJ, Schroy PC, et al, et al. Understanding the contribution of family history to colorectal cancer risk and its clinical implications: a state-of-the-science review. Cancer. 2016;122((17)):2633–45. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, et al. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300((23)):2765–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Toronto(ON): Cancer screening in Canada: overview of screening participation for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer (2015) [Internet] Available from: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/cancer-screening-participation-overview/ [Google Scholar]

- Wong MC, Ching JY, Chan VC, et al, choice vs, et al. Informed choice vs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109((7)):1072–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Add/remove data: health characteristics, annual estimates. Statistics Canada. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1310009601. [Google Scholar]