Abstract

Objectives

To explore the relative risks of preterm birth—both overall and stratified into 3 groups (late, moderate, and extreme prematurity)—associated with maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity (ie, birthplace) combined.

Study design

This was a retrospective cross-sectional cohort study of women delivering a live birth in Pennsylvania from 2011 to 2014 (n = 4 499 259). Log binomial and multinomial regression analyses determined the relative risks of each strata of preterm birth by racial/ethnic/native category, after adjusting for maternal sociodemographic, medical comorbidities, and birth year.

Results

Foreign-born women overall had lower relative risks of both overall preterm birth and each strata of prematurity when examined en bloc. However, when considering maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity together, the relative risk of preterm birth for women in different racial/ethnic/nativity groups varied by preterm strata and by race. Being foreign-born appeared protective for late prematurity. However, only foreign-born White women had lower adjusted relative risks of moderate and extreme preterm birth compared with reference groups. All ethnic/native sub-groups of Black women had a significantly increased risk of extreme preterm births compared with US born non-Hispanic White women.

Conclusions

Race, ethnicity, and nativity contribute differently to varying levels of prematurity. Future research involving birth outcome disparities may benefit by taking a more granular approach to the outcome of preterm birth and considering how nativity interacts with race and ethnicity.

Despite continuing efforts to reduce preterm births in the US, approximately 1 in 10 infants is born prematurely.1 Infants born premature have greater risks of morbidity and mortality. In addition to the impact on families, infants born premature represent a significant burden on the US healthcare system, with an estimated annual cost of 26 billion dollars.2,3 Furthermore, racial disparities in the risk of preterm birth and its associated mortality persist. The rate of prematurity among infants born to Black women is ~50% greater than among White women.4 In addition, Black infants have a greater mortality than White infants of the same gestational age.5–7 In contrast, Hispanic/Latinx women have been shown to have similar rates of preterm birth as non-Hispanic White women, despite Hispanic women sharing many of risk factors for preterm birth that Black women face.8 This phenomenon has been termed the “Hispanic paradox.”8

However, existing research on birth outcome disparities by ethnicity has focused on Hispanic ethnicity and traditionally grouped all Hispanic women together, despite the heterogeneity of individuals who self-report.9,10 Data suggest that birth outcomes may vary among Hispanic women by race or nativity. White Hispanic infants have been shown to have lower mortality rates than Black Hispanic infants,11 and Hispanic women who are foreign-born appear to have lower rates of adverse birth outcomes overall than Hispanic women who were born in the US.12,13 This potentially protective impact of immigrant status also has been noted among non-Hispanic women, with one study finding that foreign-born non-Hispanic Black women having lower rates of preterm birth compared with US-born non-Hispanic Black women.14 Researchers have come to understand that the Hispanic paradox may be better framed by the more encompassing concept of the immigrant paradox.13 Scholars have stressed the importance of examining the intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and nativity when studying immigrant health outcomes due to the differential ways in which immigrants of different racial/ethnic backgrounds experience individual and structural forms of racism.15 There is limited research that examines the relationship between preterm birth and the intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and nativity.16,17

Another limitation to existing preterm birth disparities literature relates to how prematurity is examined. Most studies of preterm birth examine all infants born at fewer than 37 weeks as a binary outcome.5,18 Nearly three-quarters of infants born prematurely are born between 34 and 366/7 weeks and thus are considered infants who are “late” preterm.2 However, much of the prematurity literature focuses on the outcomes of infants born extremely preterm (ie, infants born at less <29 weeks of gestation), given their high rates of morbidity and mortality, despite the fact that they make up at most 1% of all infants born preterm.19

This study was designed to address these gaps by exploring the risk of stratified definitions of prematurity associated with maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity combined. We hypothesized that having a foreign-born mother would confer an advantage with respect to prematurity, irrespective of race/ethnicity or strata of prematurity.

Methods

For this study, we used birth certificates for live births from all in-hospital deliveries for all infants born in Pennsylvania January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2014 (n = 924 848). Before 2011, birth certificates did not record a mother’s nativity. We excluded infants missing variables of interests (ie, maternal race, ethnicity, nativity, gestational age) (n = 403 116); infants who had a gestational age or birth weight considered an outlier (gestational age <23 weeks, greater than 44 weeks or who weighed <400 g, >8000 g, or who were more than 5 SDs from the mean birth weight for that infant’s gestational age) (n = 3108); multiples (n = 17 970); and infants with congenital anomalies (n = 1395). This led to a final cohort of 499 259 infants.

Variables of Interest

Pennsylvania uses the US standard birth certificate form that was revised in 2003, which asks birth mothers to list the state, territory, or foreign country where they were born.20 Ethnicity is documented by asking birth mothers whether they are “Spanish/Hispanic/Latina.” For our primary independent variable, we created a composite race/ethnicity/nativity variable that divided mothers into the following 8 mutually exclusive categories: US-born non-Hispanic White, US-born non-Hispanic Black, US-born Hispanic White, US-born Hispanic Black, foreign-born non-Hispanic White, foreign-born non-Hispanic Black, foreign-born Hispanic White, and other. Foreign-born Hispanic Black women were included in “other,” as their small sample size in our population (n = 194 or 0.04% of the study cohort) precluded them from being analyzed separately. In addition, our “other” category consisted of women who self-identified with the following races: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, other Asian, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, Other Pacific Islander, other, don’t know/not sure, Refused. Maternal race/ethnicity is documented on birth certificates through maternal self-report.

Our primary outcomes were preterm birth overall and stratified. Infants were stratified by gestational age at birth into 4 groups: term (≥37 weeks), late preterm (34–366/7 weeks), moderately preterm (29–336/7 weeks), and extremely preterm (<29 weeks).

We examined the following maternal sociodemographic covariates gathered from birth certificates due to their known association with preterm birth: age, marital status, insurance type, educational level, and prenatal tobacco use. We also constructed a composite binary covariate of maternal comorbid medical conditions associated with prematurity in the literature.21,22 This maternal composite covariate was coded as “yes” if a woman had at least 1 of the following comorbid conditions: any history of diabetes, any history of hypertension, prepregnancy diabetes, or prepregnancy hypertension. Adjusted models also included year fixed effects to account for unobserved factors changing each year that were common to all births.

Statistical Analyses

Infant and maternal characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics and compared using χ2 analyses for categorical variables and t tests for continuous values. We also described the prevalence of each stratum of prematurity by maternal race/ethnicity/nativity.

In our multivariable analyses, we first examined the relationship between nativity and preterm birth. We used log binomial regression models to calculate the relative risk of preterm birth for all foreign-born women compared with US-born women. Then, we estimated the risk of preterm birth for each racial/ethnic/native group using US-born non-Hispanic White women as the reference group. Post-estimation linear comparisons compared preterm births within racial/ethnic groups across nativity categories using Bonferroni-adjusted P values and confidence intervals.

Second, we analyzed the relationship between nativity and stratified preterm birth using multinomial logistic regression models to calculate the relative risk of experiencing stratified preterm birth (extreme, moderate, and late) for foreign-born women compared with US-born women overall. We then used multinomial models to explore the relative risk of extreme, moderate, and late preterm birth for each racial/ethnic/native group again using US-born non-Hispanic White women as the reference group.

All models were first run unadjusted then adjusted for maternal sociodemographics and comorbidities. All tests of significance were 2-tailed with alpha set to 0.05 except where Bonferroni correction is noted. All data were analyzed in Stata, version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Maternal demographic characteristics stratified by race, ethnicity, and nativity are shown in Table I. In this cohort, traditional risk factors for poor birth outcomes did not consistently vary by whether women were US or foreign-born. For instance, foreign-born women overall were more often married and endorsed tobacco use less than US-born women. However, education and insurance related risk factors were not the same for all racial/ethnic subgroups of foreign-born women compared with their US-born counterparts. For instance, a larger proportion of foreign-born Hispanic White women were uninsured and reported low education levels than US-born Hispanic White women. Maternal comorbidities that increase risk for preterm birth were similar across racial/ethnic subgroups when compared by nativity (Table II; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table I.

Maternal and infant demographics by race, ethnicity, and nativity

| Demographics | US-born NHW | US-born NHB | US-born HW | US-born HB | Foreign-born NHW | Foreign-born NHB | Foreign-born HW | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 328 513 | n = 61 589 | n = 8179 | n = 11 913 | n = 11 260 | n = 7348 | n = 2804 | n = 77 653 | |

| Maternal age, y, mean (SD) | 28.8 (5.6) | 25.7 (5.9) | 26.1 (5.9) | 24.4 (5.4) | 30.6 (5.3) | 30.3 (5.8) | 29.5 (5.9) | 27.4 (6.2) |

| Married, % | 66.1 | 16.8 | 38.7 | 18.0 | 87.1 | 39.9 | 36.0 | 51.8 |

| Insurance type, % | ||||||||

| Public | 24.4 | 61.8 | 51.6 | 63.6 | 23.7 | 42.0 | 33.6 | 47.0 |

| Private | 69.9 | 30.2 | 40.5 | 27.6 | 68.9 | 47.2 | 40.7 | 41.2 |

| Uninured/other | 5.7 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 7.4 | 10.8 | 25.7 | 11.9 |

| Education, % | ||||||||

| None or some high school | 8.1 | 17.8 | 21.3 | 24.2 | 4.5 | 12.9 | 32.4 | 23.6 |

| High school diploma | 23.4 | 37.5 | 31.3 | 34.7 | 15.4 | 27.9 | 23.7 | 27.9 |

| At least some college | 68.4 | 44.3 | 47.2 | 40.5 | 79.6 | 57.8 | 43.1 | 46.5 |

| Unknown | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| Tobacco use, % | 24.7 | 20.8 | 24.4 | 24.6 | 9.9 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 15.0 |

HB, Hispanic Black; HW, Hispanic White; NHB, non-Hispanic Black; NHW, non-Hispanic White.

P values for all comparisons across columns for each row were <.001. Bonferroni correction level of significance for a P value set at .01.

Table II.

Pregnancy characteristics by race, ethnicity, and nativity

| Characteristics | US-born NHW | US-born NHB | US-born HW | US-born HB | Foreign-born NHW |

Foreign-born NHB |

Foreign-born HW |

Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age, wk, mean (SD) | 38.8 (1.8) | 38.4 (2.3) | 38.7 (1.8) | 38.5 (2.2) | 39.0 (1.6) | 38.7 (2.1) | 38.9 (1.6) | 38.7 (2.0) |

| Preterm births, % | 6.7 | 10.7 | 8.0 | 9.3 | 5.1 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 7.9 |

| Extremely | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Moderately | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Late | 5.1 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 5.6 |

| Sex (% male) | 48.8 | 49.0 | 49.9 | 47.5 | 48.4 | 49.4 | 50.6 | 48.8 |

| Birth weight, g, mean (SD) | 3372.5 (544.3) | 3129.5 (600.7) | 3281.6 (542.7) | 3159.5 (569.4) | 3409.2 (518.4) | 3266.9 (586.6) | 3374.3 (501.5) | 3231.3 (554.2) |

| Maternal medical comorbidities, % | 11.1 | 14.6 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 13.9 | 11.1 | 11.6 |

HB, Hispanic Black; HW, Hispanic White; NHB, non-Hispanic Black; NHW, non-Hispanic White.

P value for comparisons across columns for each row were all <.001, except for sex (P = .120) Bonferroni correction level of significance for a P value was set at .01.

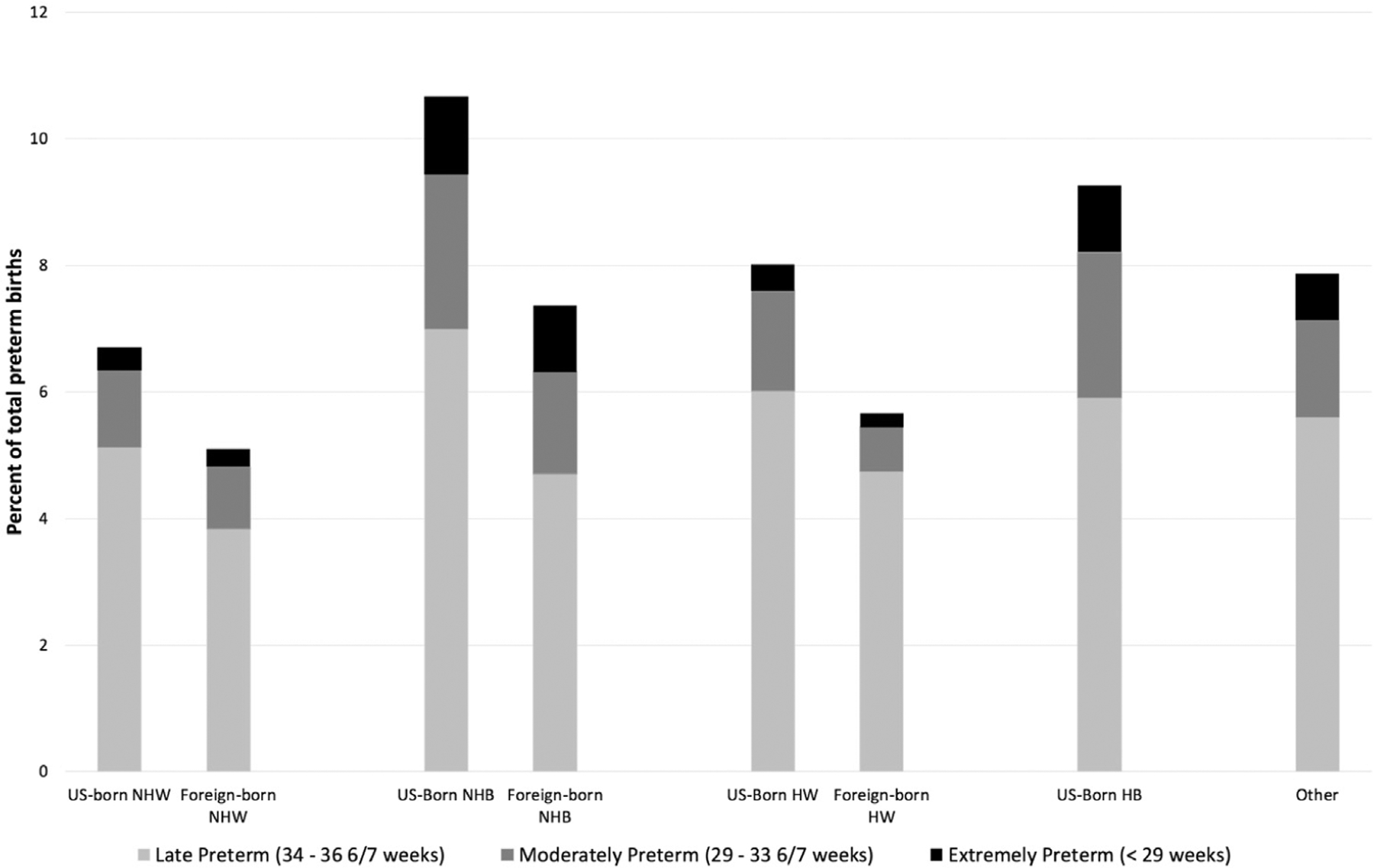

In our cohort, 7.4% of infants were born preterm overall, which reflects both the time period of the study and the fact that Pennsylvania preterm birth rates are typically lower than the US average. Of the infants born preterm, 0.6% were extremely preterm, 1.4% were moderately preterm, and 5.4% were late preterm (Figure 1 and Table II). Overall, women who were foreign-born had a lower rate of preterm birth compared with US-born women (6.1% vs 7.5% respectively, P = .001). Among women who were foreign-born, non-Hispanic White women had the lowest rates of preterm birth overall (5.1%), and non-Hispanic Black women had the highest rate (7.4%, Table II). Non-Hispanic Black women also had the greatest rate of preterm birth among US-born women.

Figure 1.

Percent of infants in each strata of prematurity by maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity (N = 499 259). HB, Hispanic Black; HW, Hispanic White; NHB, non-Hispanic Black; NHW, non-Hispanic White.

In models that only looked at nativity, we found that foreign-born women had a lower relative risk of preterm birth than US-born women after adjusting for covariates (adjusted relative risk [aRR] 0.81, 95% CI 0.78–0.94). When we looked at overall risk of preterm birth for women categorized by race, ethnicity, and nativity combined using US-born non-Hispanic White women as the reference group, we found all other US-born groups of women had a significantly increased relative risk of preterm birth (Table III; available at www.jpeds.com). Furthermore, when considering all possible pairwise comparisons among the groups of women, we found that foreign-born non-Hispanic White women and foreign-born Hispanic White women did not significantly differ from each other but both had lower aRRs of preterm birth than all the other racial/ethnic/native categories (Table IV; available at www.jpeds.com). Foreign-born non-Hispanic Black women only had a lower relative risk of preterm birth when compared with US-born non-Hispanic Black (aRR 0.74, 95% CI 0.65–0.85).

Table III.

Unadjusted and aRR (95% CI) of preterm birth by maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity

| Relative risks | US-born NHW | US-born NHB | US-born HW | US-born HB | Foreign-born NHW | Foreign-born NHB | Foreign-born HW | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Ref | 1.59 (1.55–1.63) | 1.19 (1.11–1.29) | 1.38 (1.20–1.59) | 0.76 (0.70–0.82) | 1.10 (1.01–1.19) | 0.85 (0.73–0.98) | 1.17 (1.14–1.20) |

| Adjusted* | Ref | 1.36 (1.32–1.40) | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 1.24 (1.08–1.43) | 0.81 (0.75–0.88) | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) | 0.77 (0.66–0.89) | 1.07 (1.04–1.11) |

Models adjusted for maternal age, marital status, insurance type, educational level, medical comorbidities, tobacco use, and infant birth year. Significant relative risks and aRRs are shown in bold.

Table IV.

Pairwise comparisons of aRR of preterm birth by race, ethnicity, and nativity combined

| Comparator groups | Reference group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US-born NHW | US-born NHB | US-born HW | US-born HB | Foreign-born NHW | Foreign-born NHB | |

| aRR (Bonferroni-corrected 95% CI) | ||||||

| US-born NHB | 1.36 (1.30–1.43) | – | – | – | – | – |

| US-born HB | 1.11 (0.99–1.25) | 0.91 (0.73–1.14) | – | – | – | – |

| US-born HW | 1.24 (0.99–1.55) | 0.82 (0.72–0.92) | 0.89 (0.70–1.15) | – | – | – |

| Foreign-born NHW | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | 0.59 (0.52–0.68) | 0.65 (0.50–0.84) | 0.73 (0.61–0.87) | – | – |

| Foreign-born NHB | 1.01 (0.89–1.15) | 0.74 (0.65–0.85) | 0.82 (0.63–1.05) | 0.91 (0.77–1.08) | 1.25 (1.04–1.50) | – |

| Foreign-born HW | 0.77 (0.60–0.98) | 0.56 (0.44–0.72) | 0.62 (0.45–0.86) | 0.69 (0.53–0.91) | 0.95 (0.72–1.25) | 0.76 (0.58–0.999) |

Models adjusted for maternal age, marital status, insurance type, educational level, medical comorbidities, tobacco use, and infant birth year. Bonferroni-corrected significant aRRs are shown in bold.

We then explored the impact of nativity on risk of stratified preterm. Compared with US-born women, foreign-born women had lower aRRs across all strata of prematurity: extreme preterm birth, aRR 0.84 (95% CI 0.74–0.96); moderate, aRR 0.80 (95% CI 0.73–0.87); and late preterm birth, Arr 0.79 (95% CI 0.76–0.83).

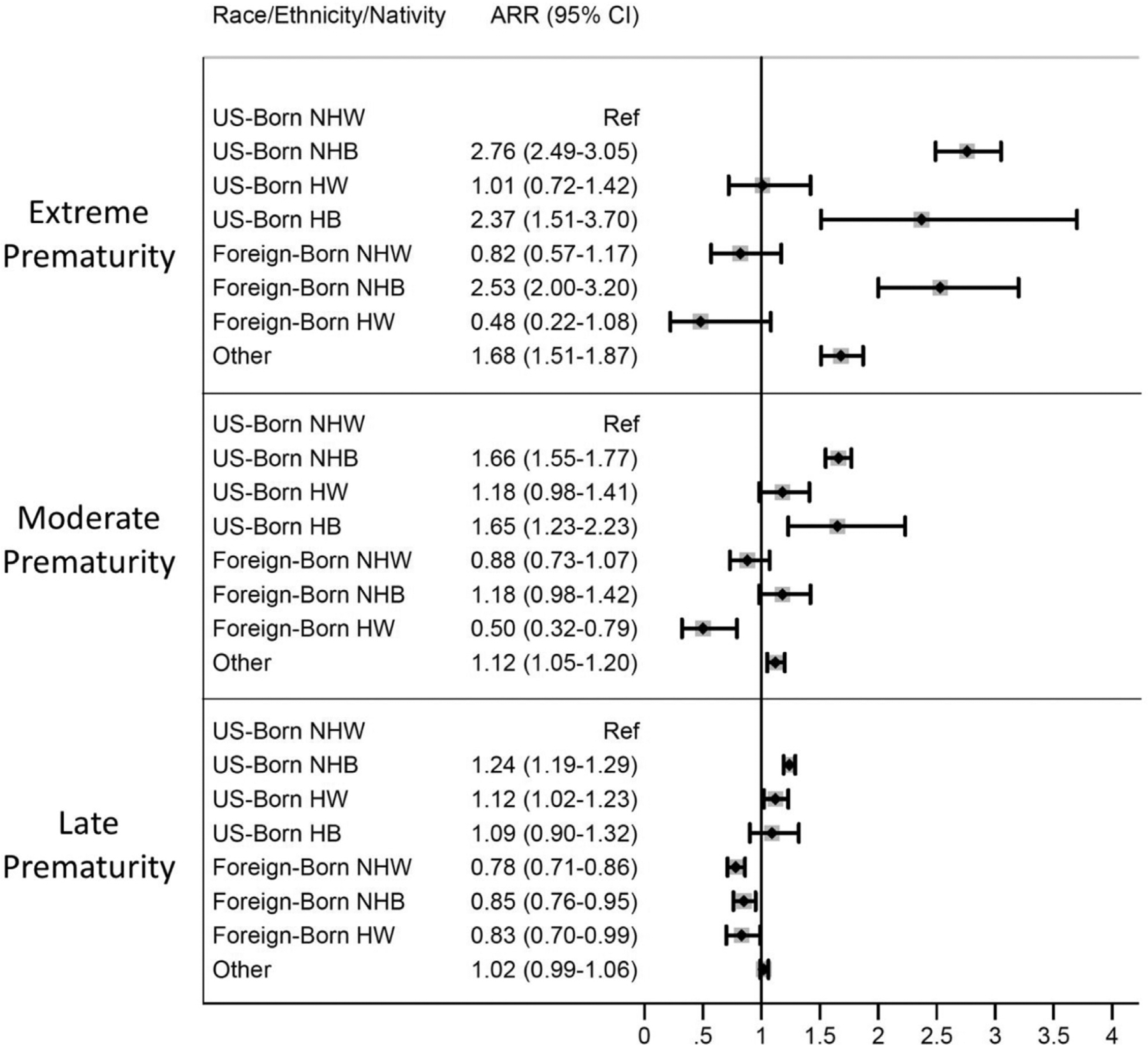

With regards to the relative risk of late and moderate preterm birth by race, ethnicity, and nativity combined, we found that all 3 categories of foreign-born women (foreign-born non-Hispanic White women, foreign-born non-Hispanic Black, and foreign-born Hispanic White) were less likely to deliver infants who were late preterm than US-born non-Hispanic White women (Figure 2). However, only foreign-born Hispanic White women had a lower relative risk of moderate preterm birth compared with US-born non-Hispanic White women (Figure 2). Conversely, within the three US-born categories, no racial/ethnic group had a lower risk of delivering a moderately or late preterm infant compared with US-born non-Hispanic White women. US-born non-Hispanic Black had a greater risk of delivering both moderate and late preterm infants than a US-born non-Hispanic White woman. US-born Hispanic Black women also had an increased risk of delivering an infant born moderately preterm, and US-born Hispanic White women had an increased risk of delivering an infant born late preterm compared with reference (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

aRR of extreme, moderate, and late preterm birth by maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity (N = 499 259). Models were adjusted for maternal age, marital status, insurance, education, tobacco use, medical comorbidities, and infant birth year.

With respect to delivering an infant who was extremely preterm, the relative risks were more than 2 times greater for all categories of Black women (US-born non-Hispanic, US-born Hispanic, and foreign-born non-Hispanic) compared with US-born non-Hispanic White women. No other racial/ethnic/native group’s aRR of extreme preterm birth was significantly different than the US-born non-Hispanic White reference group, except for the “other” group. The point estimates of unadjusted (Table V; available at www.jpeds.com) and adjusted models (Figure 2) were similar.

Table V.

Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) of stratified preterm birth by maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity

| Extreme preterm birth (<29 weeks) | Moderate preterm birth (29–336/7 weeks) | Late preterm birth (34–366/7 weeks) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US-born | |||

| NHW | Ref | ref | ref |

| NHB | 3.44 (3.14–3.77) | 2.10 (1.98–2.23) | 1.43 (1.38–1.48) |

| HW | 1.13 (0.80–1.59) | 1.31 (1.10–1.56) | 1.19 (1.09–1.31) |

| HB | 2.88 (1.85–4.49) | 1.94 (1.43–2.62) | 1.19 (0.98–1.44) |

| Foreign-born | |||

| NHW | 0.73 (0.51–1.04) | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) | 0.74 (0.67–0.81) |

| NHB | 2.83 (2.24–3.56) | 1.32 (1.10–1.59) | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) |

| HW | 0.57 (0.25–1.27) | 0.58 (0.37–0.90) | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) |

| Other | 2.00 (1.81–2.21) | 1.27 (1.19–1.36) | 1.11 (1.07–1.14) |

Significant relative risks are shown in bold.

Postestimation Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons of risk of each of the strata of prematurity indicated that compared with all US-born categories, foreign-born women of each racial/ethnic group had a decreased risk of late preterm birth (Table VI). Foreign-born non-Hispanic Black women’s risk of moderate and extreme preterm birth was not significantly different than other groups except for 2 instances: they were 50% more likely to deliver an infant born extremely preterm compared with US-born Hispanic White women (aRR 2.5, 95% CI 1.67–3.76) and 30% less likely to deliver am infant born moderately preterm compared with US-born non-Hispanic Black women (aRR 0.71, 95% CI 0.59–0.86) (Table VI). Foreign-born White women (both Hispanic and non-Hispanic) showed the same pattern across the strata of prematurity, evidencing a lower risk at each stratum except for extreme prematurity in comparison with US-born Hispanic White women (Table VI).

Table VI.

Pairwise comparisons of relative risk of stratified preterm birth by maternal race, ethnicity, and nativity

| Extreme preterm birth | Moderate preterm birth | Late preterm birth | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference groups | Comparison group | aRR (Bonferroni-corrected 95% CI) | ||

| US-born HW | ||||

| Foreign-born NHB | 2.5 (1.67–3.76) | 1.01 (0.78–1.30) | 0.76 (0.66–0.88) | |

| Foreign-born NHW | 0.81 (0.50–1.32) | 0.75 (0.58–0.97) | 0.69 (0.61–0.79) | |

| Foreign-born HW | 0.48 (0.21–1.14) | 0.43 (0.27–0.69) | 0.74 (0.61–0.90) | |

| US-born NHB | ||||

| Foreign-born NHB | 0.92 (0.72–1.17) | 0.71 (0.59–0.86) | 0.69 (0.61–0.77) | |

| Foreign-born NHW | 0.29 (0.21–0.43) | 0.53 (0.44–0.65) | 0.63 (0.57–0.70) | |

| Foreign-born HW | 0.18 (0.08–0.39) | 0.30 (0.19–0.47) | 0.67 (0.56–0.80) | |

| US-born HB | ||||

| Foreign-born NHB | 1.07 (0.65–1.76) | 0.72 (0.50–1.02) | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | |

| Foreign-born NHW | 0.35 (0.20–0.61) | 0.53 (0.37–0.76) | 0.72 (0.58–0.89) | |

| Foreign-born HW | 0.20 (0.08–0.51) | 0.31 (0.18–0.52) | 0.76 (0.59–0.99) | |

Model adjusted for maternal age, marital status, insurance, education, tobacco use, medical comorbidities, and infant birth year. These estimates were derived from postestimation linear comparisons and Bonferroni adjusted for multiple comparisons. Significant aRRs are shown in bold.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of 3 years’ worth of births in Pennsylvania, we found that the relationship between maternal nativity and preterm birth was variable across race, ethnicity, and strata of prematurity. Compared with US-born non-Hispanic White women, all foreign-born categories of women had a lower risk of late preterm birth. However, only foreign-born Hispanic White women had a lower risk of both moderate and extreme preterm birth compared with US-born non-Hispanic White women. Being foreign-born did not mitigate the increased risk of extreme prematurity Black women experienced compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts.

Some of our findings parallel what others have found. For instance, using data from 2008, Elo et al found that US born non-Hispanic Black women had greater rates of preterm birth than foreign-born non-Hispanic Black women.14 Similarly, Mydam et al noted that US-born Hispanic Black women had greater rates of infants with low birth weight than foreign-born Hispanic Black women.12 These previous studies appear to support the immigrant birth outcomes paradox, the epidemiologic phenomenon whereby foreign-born women in the US appear to experience decreased risk of adverse birth outcomes like preterm birth and low birth weight than US-born women, despite experiencing high rates of known risk factors for poor birth outcomes, such as lower socioeconomic status and decreased access to health insurance.8 We similarly found that foreign-born women had a decreased risk of preterm birth overall and within each racial/ethnic group, a decreased risk of late prematurity.

Using New York City data from 1995 to 2003, Stein et al looked at risk of adverse perinatal outcomes by maternal ethnic ancestry using both country of origin and larger geographic region of origin such as North Africa, non-Hispanic Caribbean, and South America.23 For preterm birth, they stratified infants born preterm into 2 categories, with the early strata encompassing infants born 22–31 weeks of gestation and the late preterm group including infants 32–36 weeks of gestation.23 They found significant heterogeneity with respect to risk of adverse outcomes by maternal country or region in origin but did report an increased risk of preterm birth among most foreign-born non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic groups compared with the non-Hispanic White reference group, with the notable exception of women from North Africa and East Asia. They reported that the effect of maternal ethnicity was greater on early preterm birth, with seemingly attenuated aORs among women who delivered late preterm infants.23

Our study extends this previous work in several important ways. First, we considered preterm birth in a stratified manner, given the evidence that outcomes among infants born moderately preterm are different than those among infants born extremely preterm.19 Second, we did not find a consistent protective relationship between nativity and risk of preterm birth in this cohort at every strata of prematurity. Foreign-born women’s risk of preterm birth compared with US-born non-Hispanic White women depended on which strata of prematurity was being examined and what racial/ethnic group a foreign-born woman belonged to (Figure 2). Although nativity appeared protective for late prematurity among all the foreign-born women in our cohort, for extreme prematurity, it only appeared to be protective for foreign-born White women. Thus, we found evidence to suggest that the drivers of extreme prematurity may differ from the drivers of moderate or late prematurity.

The immigrant paradox reflects the epidemiologic observation that immigrants to Western countries tend to be relatively healthy or perhaps healthier than native-born populations in the receiving country.24 Notably, it has also been documented that the relative health advantage immigrants appear to possess diminishes over time within an individuals’ life, perhaps as a result of cumulative exposure to inadequate healthcare and stress related to socioeconomic challenges and discrimination.8,24 However, we did not find consistent evidence of the immigrant paradox with respect to all strata of preterm birth. The racial disparities we found within foreign-born women indicates that there may be different mechanistic pathways leading to the outcomes of early, moderate, or late prematurity. This may reflect the intersectional ways in which immigrants of different races, skin colors, socioeconomic classes, and even sex identities are impacted by both individual and structural determinants of health.15 However, as these research questions are explored, it will be important to consider what race is serving as a proxy for when it comes to the outcomes of early vs late prematurity, recognizing it may reflect differential risk markers for each of these pathways.25 Racial categories were historically created using physical characteristics such as skin color for the purposes of discriminatory socioeconomic and political policies.26 As a result, membership in certain racial/ethnic groups continues to be a risk marker for adverse health outcomes due to structural race-based sociopolitical barriers to health and wealth that persist to this day.27 Race can serve as a proxy variable for such barriers, otherwise known as structural forms of racism, as well as a proxy for individual experiences of stress and discrimination due to interpersonal or internalized racism.25

Our findings of racial disparities within foreign-born women with respect to strata of prematurity indicate that conceptual models which group all preterm births together, all Hispanic women together or all foreign-born women together lack important granularity that will limit our understanding of the root causes of preterm birth disparities. It may not be sufficient to link race to increased levels of stress at any given time as the potential explanatory pathway for preterm birth. There may be differential impacts on prematurity depending on the types of stressor, when stressors are experienced, their overall magnitude and cumulative exposure.28 Significant socioeconomic or sociopolitical processes are associated with extreme preterm birth risk.29,30

There are several limitations to our analysis. Our study was dependent on birth certificate coding for maternal information; misdiagnosis or underreporting of maternal information such as comorbidities could affect the categorization of our covariates. We were also dependent on maternal self-identification place of birth, which might have led to underreporting of foreign-born status, although previous research in immigrant communities has shown this to be uncommon.31 We were not able to account for specific country of origin, nor assess for variables related to acculturation such as time in country, which are factors hypothesized to impact risk of adverse health outcomes.8,23,32 To truly tease apart drivers of preterm birth disparities that exist by race, ethnicity, and nativity, future research may benefit from the combination of administrative dataset research with questionnaire or interview-based research in order to better capture experiences with individual and structural racism and discrimination. Lastly, our stratified preterm birth analyses were limited by sample sizes within certain race/ethnicity/nativity categories. This led us to exclude an important category of women—foreign-born Hispanic Black women—from our analyses, making it difficult to make conclusions about all Black women or all Hispanic women in our cohort.

In this study, we found evidence supporting the immigrant paradox for foreign-born White women, irrespective of ethnicity. However, our results also indicate that foreign birth may not be associated with the same reduction in preterm birth risk for Black and Hispanic women for every strata of prematurity. Future research aimed at mitigating racial disparities should be grounded in conceptual frameworks that better understand what nativity and race represent in the context of preterm birth and consider that risk drivers may differ for different levels of prematurity. Such research may allow for more tailored interventions and policies with a greater chance of improving perinatal equity among diverse groups of women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by internal professional development funds from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We acknowledge Dominique G. Ruggieri, PhD, for providing critical review to early drafts of this manuscript. D. R. declares no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- aRR

Adjusted relative risk

Footnotes

Portions of this study were presented at the National Conference and Exhibition of the American Academy of Pediatrics, October 25th, 2019, New Orleans, LA; and the American Public Health Association Conference, November 5th, 2019, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Ferré C, Callaghan W, Olson C, Sharma A, Barfield W. Effects of Maternal Age and Age-Specific Preterm Birth Rates on Overall Preterm Birth Rates—United States, 2007 and 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purisch SE, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Epidemiology of preterm birth. Semin Perinatol 2017;41:387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matoba N, Collins JW. Racial disparity in infant mortality. Semin Perinatol 2017;41:354–9. 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief 2020:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JG, Rogers EE, Baer RJ, Oltman SP, Paynter R, Partridge JC, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in preterm infant mortality and severe morbidity: a population-based study. Neonatology 2018;113:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barfield WD. Public health implications of very preterm birth. Clin Perinatol 2018;45:565–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigurdson K, Mitchell B, Liu J, Morton C, Gould JB, Lee HC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2019;144:e20183114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montoya-Williams D, Williamson VG, Cardel M, Fuentes-Afflick E, Maldonado-Molina M, Thompson L. The Hispanic/Latinx perinatal paradox in the United States: a scoping review and recommendations to guide future research. J Immigr Minor Health 2021;23:1078–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Neonatal Intensive-Care Unit Admission of Infants with Very Low Birth Weight—19 States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report [Internet]. 2010 Nov 12;59. Accessed February 26, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm5944.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Govande V, Ballard AR, Koneru M, Beeram M. Trends in the neonatal mortality rate in the last decade with respect to demographic factors and health care resources. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2015;28:304–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice WS, Goldfarb SS, Brisendine AE, Burrows S, Wingate MS. Disparities in infant mortality by race among Hispanic and non-Hispanic infants. Matern Child Health J 2017;21:1581–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mydam J, David RJ, Rankin KM, Collins JW. Low birth weight among infants born to Black Latina women in the United States. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:538–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flores MES, Simonsen SE, Manuck TA, Dyer JM, Turok DK. The “Latina epidemiologic paradox”: contrasting patterns of adverse birth outcomes in U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinas. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elo IT, Vang Z, Culhane JF. Variation in birth outcomes by mother’s country of birth among non-Hispanic black women in the United States. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:2371–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:2099–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blebu BE, Ro A, Kane JB, Bruckner TA. An examination of preterm birth and residential social context among Black immigrant women in California, 2007–2010. J Community Health 2019;44:857–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ro A, Bruckner TA, Duquette-Rury L. Immigrant apprehensions and birth outcomes: evidence from California birth records 2008–2015. Soc Sci Med 2020;249:112849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kochanek KD, Murphy S, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief 2017: 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh MC, Bell EF, Kandefer S, Saha S, Carlo WA, D’angio CT, et al. Neonatal outcomes of moderately preterm infants compared to extremely preterm infants. Pediatr Res 2017;82:297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revisions of the U.S. Standard Certificates and Reports [Internet]. 2019. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/revisions-of-the-us-standard-certificates-and-reports.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fnchs%2Fnvss%2Fvital_certificate_revisions.htm

- 21.Crawford S, Joshi N, Boulet SL, Bailey MA, Hood M-E, Manning SE, et al. Maternal racial and ethnic disparities in neonatal birth outcomes with and without assisted reproduction. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129: 1022–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medical and pregnancy conditions associated with preterm birth. In: Behrman RE, Butler AS, eds. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein CR, Savitz DA, Janevic T, Ananth CV, Kaufman JS, Herring AH, et al. Maternal ethnic ancestry and adverse perinatal outcomes in New York City. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:584.e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markides KS, Rote S. The healthy immigrant effect and aging in the United States and other western countries. Gerontologist 2019;59:205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, Lemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borrell LN, Elhawary JR, Fuentes-Afflick E, Witonsky J, Bhakta N, Wu AHB, et al. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine—a time for reckoning with racism. N Engl J Med 2021;384:474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan JB, Bennett T. Use of race and ethnicity in biomedical publication. JAMA 2003;289:2709–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almeida J, Bécares L, Erbetta K, Bettegowda VR, Ahluwalia IB. Racial/ethnic inequities in low birth weight and preterm birth: the role of multiple forms of stress. Matern Child Health J 2018;22:1154–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catalano R, Karasek D, Bruckner T, Casey JA, Saxton K, Ncube CN, et al. African American unemployment and the disparity in periviable births. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 10.1007/s40615-021-01022-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gemmill A, Catalano R, Alcalá H, Karasek D, Casey JA, Bruckner TA. The 2016 presidential election and periviable births among Latina women. Early Hum Dev 2020;151:105203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bachmeier JD, Van Hook J, Bean FD. Can We measure immigrants’ legal status? Lessons from two U.S. surveys. Int Migr Rev 2014;48:538–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams DR, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: sociological contributions. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51(suppl): S15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.